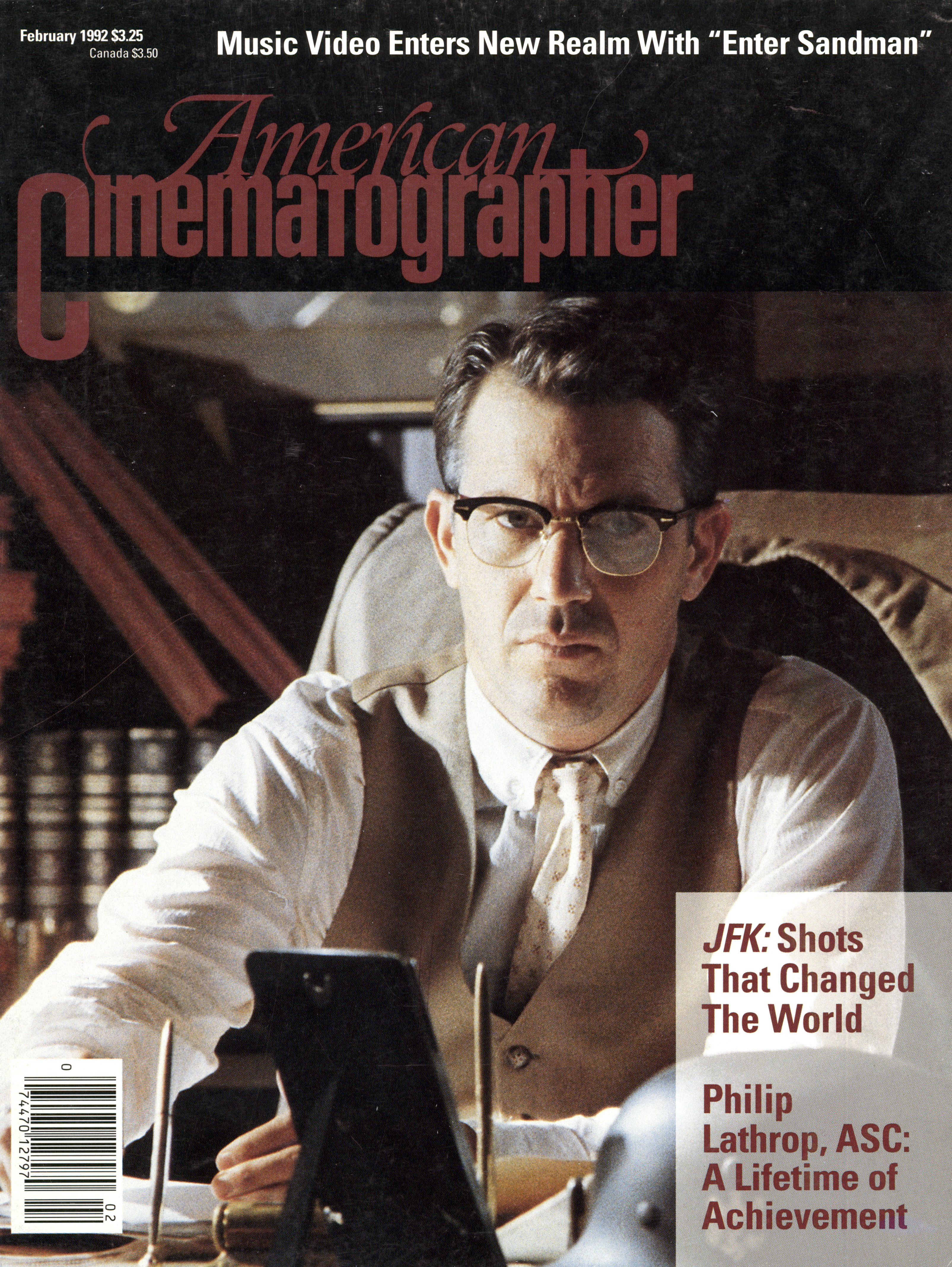

The Whys and Hows of JFK

Robert Richardson, ASC details his complex visual approach to director Oliver Stone’s cinematic “counter-myth” to the Warren Commission Report.

Unit photography by Sidney Baldwin, courtesy of Warner Bros.

In regard to the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy, there are two kinds of people. The first has a vivid memory of the day Kennedy was killed and its aftermath. They heard the words on radio and saw the pictures on TV. They remember the Zapruder film as a series of grainy images printed in Life magazine. They can tell you where they were, what they were doing, who they were with, and what they thought the moment it happened. The memories will always linger.

Others weren't born yet.

Cinematographer Robert Richardson remembers the moment, but he was too young to be touched. For Richardson, there was no cataclysmic sense that the fabric of history had been torn. The assassination of Kennedy, and the events that followed, passed him by without leaving deeply etched visual memories. It is somewhat ironic, then, that Richardson was enlisted by director Oliver Stone to recreate the unforgettable images of November 22, 1963 for an audience comprising both those who remember the day firsthand and subsequent generations who have become familiar with the event via history books and archival footage.

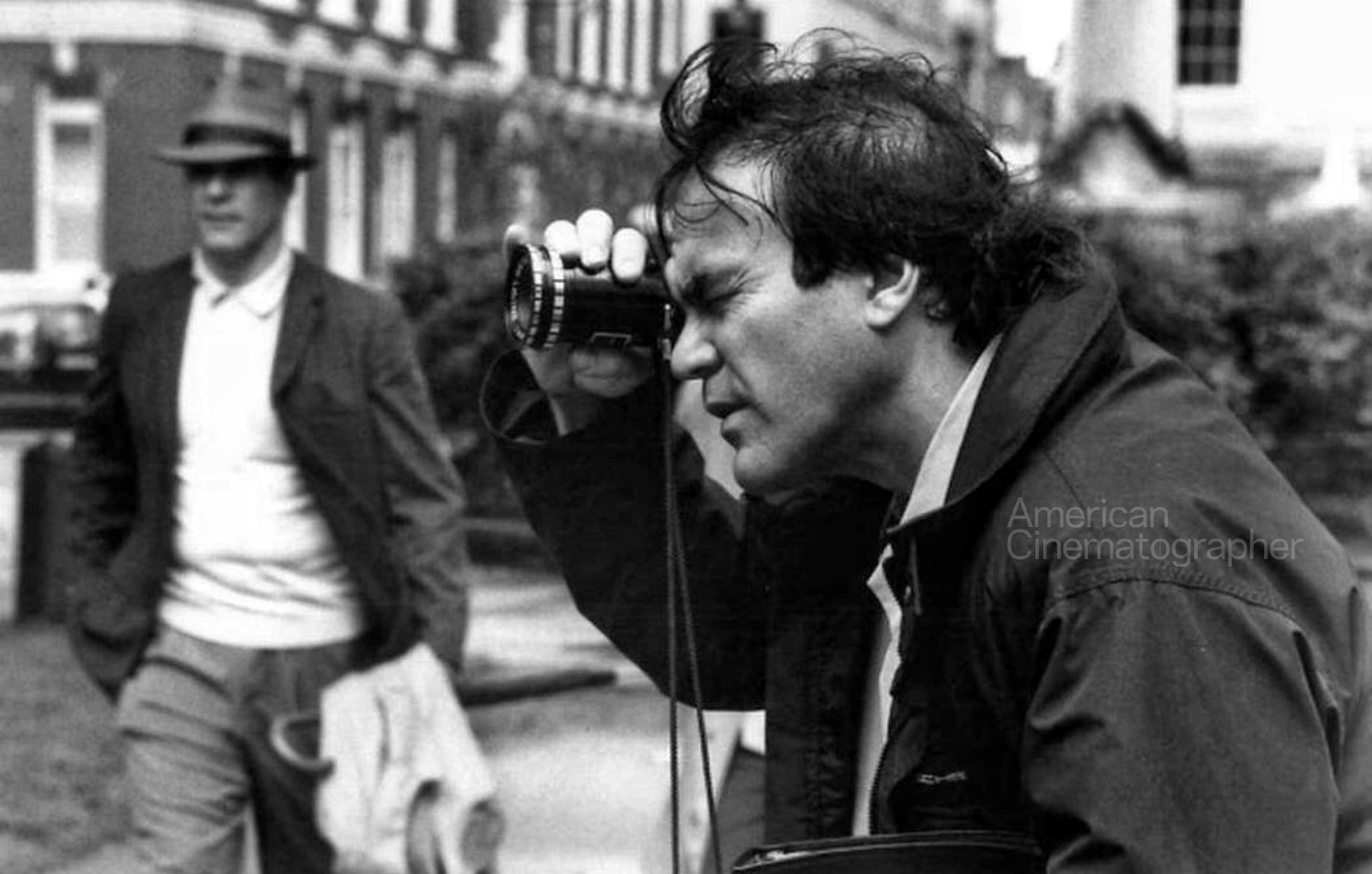

In light of Stone's reality-based approach to the film, however, Richardson's background was ideal. He first studied filmmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design, and then went on to more advanced work at the American Film Institute. For a half-dozen years afterward, he mainly shot documentaries. This training undoubtedly helped Richardson create the quasi-documentary feel that Stone sought for his incendiary big-screen investigation.

Richardson was just a week and a half into shooting City of Hope with writer-director John Sayles when he heard that Stone was thinking about tackling the Kennedy assassination as a subject. He locked thoughts of JFK out of his mind, though, to focus on the task at hand.

Around the time Richardson finished principal photography, Stone was ready to get serious about JFK. His script had nothing to do with the life of President Kennedy, and very little about how he was assassinated. It instead asked why.

“I think it will definitely be jarring. That’s our intention. You feel like you are being thrown into a memory.”

— Robert Richardson, ASC

Richardson agreed to collaborate with Stone for the seventh time in six years. The combination has been a potent one: in addition to 1991's The Doors, the cinematographer has shot Born on the Fourth of July, Talk Radio, Wall Street, Platoon and Salvador.

Upon accepting the assignment, Richardson dug deeply into the conflicting literature about the assassination. He first read the book which had initially sparked Stone's interest in the project, Jim Garrison's On the Trail of the Assassins. Garrison, a New Orleans district attorney at the time of the tragedy, had been an all-American boy who believed in the system. He went to war for his country, and became a man with a fanatical desire to see justice done. When Kennedy was killed, the subsequent investigation revealed loose strings that led to New Orleans. Garrison launched an investigation which resulted in the only trial ever held in relationship to the assassination. He believed — and still believes, along with a significant segment of the American public — that there was a conspiracy to kill the president.

Richardson also read a more recent book that Stone had optioned, Jim Marrs' Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, along with whatever else he could find that brought the story and period into sharper focus. He started thinking about the baggage much of the audience would bring to the theater. How could he recreate images that were still so vivid in the viewers' collective memory?

A diary that Richardson kept during the filming reveals much about his thought processes and how those raw ideas were translated into memorable footage. Early on, for example, he wrote:

"All the characters are hiding. Something reminds me of Robert Frank's photographs [in] The Americans. There are faces blurred by motion; for a cameraman, it appears that shadows and objects are the most available (ways) to hide identities. A sense of foreboding needs to occupy our frame... severe thunderstorms could solve the puzzle. They could help create confusion and foreboding in the frame. Aesthetically, New Orleans needs to be more visually encumbered."

Production of the film would take place primarily at practical locations in Dallas and New Orleans. Several additional sequences were filmed in Washington, D.C. There were only a few sets, the largest one a replica of the President's Oval Office.

The cast of JFK read like a Hollywood Who's Who: Kevin Costner was hired to play the centerpiece role of Garrison, while Sissy Spacek was enlisted as his wife. The powerful ensemble cast also included Kevin Bacon, Laurie Metcalf, Gary Oldman, Tommy Lee Jones, Joe Pesci, Walter Matthau, Ed Asner, Jack Lemmon and Donald Sutherland. In an interesting twist, Garrison himself was given a cameo role as Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Richardson's notes for the film's title sequence, which includes assassination footage, included the following ideas:

"The main title will clearly set the style for the opening six minutes. All the footage needs to match. We should do tests with the 8mm and 16mm. The question arises: should the film be color at this point? My feeling is dual-edged. I feel that black-and-white would give us more power, but color is closer to the truth. If we decide to shoot color, we could then desaturate the color from the screen following the hit [assassination] — drain blood from the image. Just a fleeting thought."

Richardson and Stone visualized a collage for JFK, where the selection of media was part of the message. The assassination, which occurred at Dealey Plaza in Dallas, was originally seen through the lenses of multiple 16mm news film cameras (primarily black-and-white) and the eyes of dress manufacturer and amateur photographer Abraham Zapruder, who was filming in standard 8mm. Richardson duplicated and then enhanced the image in 35mm, 16mm and Super 8 formats, which were then combined to cover the recreated assassination. A total of seven cameras and 14 film stocks were used; overall, there were 70 to 80 35mm black-and-white shots, and hundreds in 16mm.

Later, the shocking murder of Oswald, as well as other scenes etched in public memory, were captured on 16mm news film and live video. In some scenes, the actual news film is integrated, augmented and matched with new video, Super 8 and 16mm footage. Richardson recorded some of these sequences on Kodachrome and Kodacolor film. But he also hedged his bets by covering critical sequences with Eastman EXR 7248 film — a 100-speed fine-grain negative in 16mm format — "just to be sure."

The Kodachrome Super 8 blow-ups were grainy, but the texture matched the public's visual memories. Richardson also used Plus-X, DBL-X, 4X and Tri-X films, depending on the situation, since news coverage in that period was mainly in black-and-white. In all, some 2,000 opticals were required, primarily for blow-ups from the smaller formats to 35mm intermediate footage.

The original concept was to film the opening sequence in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio, which most closely simulates the almost square TV screens that most people saw. Richardson planned a transition to the 1:85:1 spherical format when Garrison began his investigation. He would then switch to the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, using anamorphic lenses, for photographing scenes occurring in 1968 and later. The idea was to broaden the frame containing the story after the documentary portion of the movie was completed.

"For a lot of reasons, but mainly because of the complexity of making opticals and time constraints, we couldn't follow that strategy," Richardson says. "Instead, we created a strong documentary feel for the first two sections of the film. We also contained the frame for those parts of the film somewhere between the 1.33:1 and 1:85:1 aspect ratios by masking the edges of the image. During the rest of the film, we used the whole anamorphic frame."

The intercutting between footage originated in different formats, and between color and black-and-white, isn't particularly subtle. "I think it will definitely be jarring," says Richardson. "That's our intention. You feel like you are being thrown into a memory. Hopefully, there will be some type of syntactical relationship, and the audience will recognize what Oliver is intending to be the principal truth of the story. That will require them to connect different visual elements."

The 35mm color live-action footage is light-years away from the gritty texture of Richardson's first films with Stone, Salvador and Platoon. It's smooth as silk, a perfect canvas for Costner's portrayal of Garrison.

The opening sequences, the Kennedy and Oswald assassinations, were filmed on 16mm without diffusion or filters on the lenses. The idea was to record stark reality; Richardson wanted nothing to come between the audience and the pictures. After he slipped into using the whole anamorphic frame, however, there was some substantial use of diffusion. It served a visual signal to the audience that they were now watching a story.

In his diary, Richardson noted that the plot is built on the strength of the opening sequence:

"Utilize the opening documentary material to establish a concrete foundation off actual reality. Let the audience move through the material, never doubting its authenticity. Using this as a basis, move away whenever the desire to accomplish the concrete arises. Once again draw in the technique and look of the found material. In the case of Dealey Plaza, nothing should be more than one generation removed from the original material shot by the news media."

As the story progresses, visual metaphors begin to appear. A little girl dressed in red runs innocently through the plaza at the moment of the killing; when Oswald shoots, hundreds of pigeons take off from their perches on a nearby building foreshadowing Oswald's own imminent flight from the law. There were no pigeons at the actual site in 1963, but Stone invoked the law of artistic license to make his point.

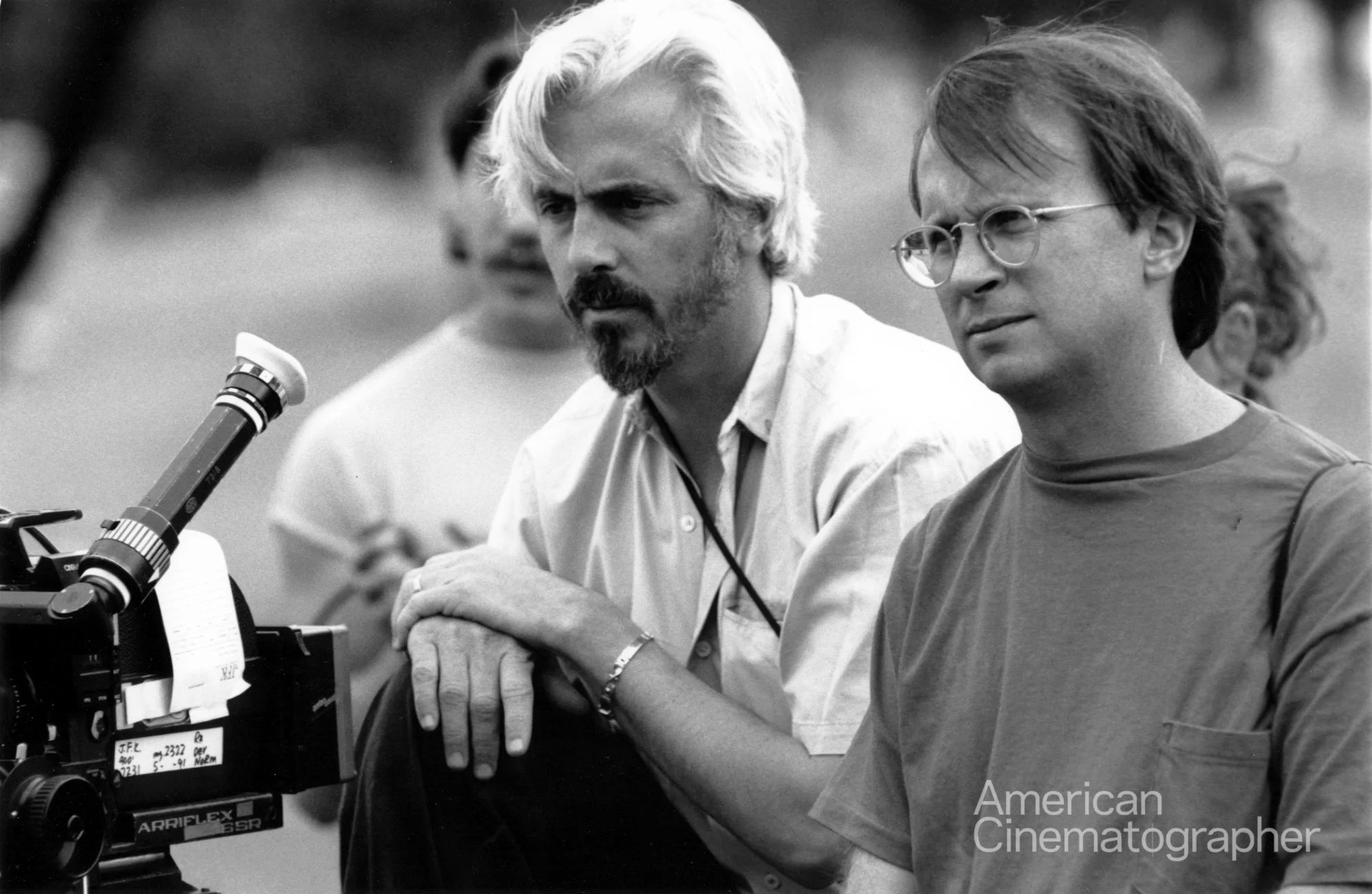

To create the multiple vantage points Stone wanted for the Dealey Plaza sequence, Richardson had two 35mm Panaflex cameras working. There were also five 16mm cameras, cleverly integrated into the setting as equipment for the news crews, in addition to a Super 8 camera.

“Oliver disdains convention. He tries to force you into things that are not classic. There’s this constant need to stretch, which forces your lighting into very diverse positions.”

On any production of such scale, it helps to consider 19th century Scottish poet Robert Bums' advice about "the best-laid plans of mice and men." Richardson's diary after the first day in Dealey Plaza offered an optimistic outlook, however:

"This has proved to be one of the smoothest first days I can remember. Oliver was in excellent spirits and well-focused. The material was essentially very good; I hope my decision to shoot 16mm does not backfire. The quality of the film is anything but beautiful. The grain, to be moderate, is horrendous in terms of blow-up, but what exactly are my options? There is very little 35mm period material, and none that I'm aware of from Dealey Plaza. It is my destiny to touch hands once again with my good old friend, 16mm film."

Dealey Plaza hasn't changed much since 1963. What had changed was redressed by production designer Victor Kempster. The sequence involving Oswald's role in the shooting was staged on the seventh floor of the book depository, instead of the sixth, where he allegedly fired on Kennedy (the sixth now houses a museum). Kempster faithfully reproduced the exact original setting.

The three cities used as locations also look remarkably like they did in 1963. The landmarks are largely the same, so the period look came, in part, from scores of vintage cars ("I don't know where they come from," says Richardson. "They just make a call, and they're there") and costuming by Marlene Stewart. "She did a remarkable job, because it wasn't a particularly interesting period," Richardson notes. "It was all suits. She didn't have many levels on which she could move."

The shoot soon began to pick up momentum:

"The days are sliding against each other with overlaps of memory for days 8, 9 and 10. We finally started shooting anamorphic 35mm color, such a treat after a week of 16mm black-and-white. Days 8 and 9 went smoothly. We completed Dealey Plaza on day 8, shooting the hobos' arrest, Oswald's escape, and a series of post-assassination interviews. Nothing serious. On day 9, we sat down to dinner with Kevin. The skies were horrible. First it rained. Then the sun came alive, and in the end, we were ablaze again. Hard to keep a match, but with a little help from the lab, I'll be fine."

Richardson covered the reenactment with Oswald in two ways. He shot with 35mm black-and-white with the cameras on tripods and dollies and he shot on 16mm black-and-white with handheld cameras. The 16mm version is meant to reproduce one reality (Garrison's) and the 35mm another (the Warren Commission's version of events). A visual clue tells the audience something about perception and the eye of the beholder. The Warren Commission and Garrison may see a scene the same way but for a subtle insert; the difference is something the audience is more likely to feel than see.

Richardson comments, "It all ends up on 35mm color print film, but the black-and-white footage has a stronger graphic quality. It's more dramatic. There are larger areas of blacks, more silhouettes and fewer soft tones. The Kodachrome has more texture than 16mm color negative film. It's very rich in contrast. Even the Super 8 film is gorgeous, though it's very grainy."

In the true spirit of credit-where-credit-is-due, he adds, "Dale Caldwell at DeLuxe Labs was the color timer. This is the third film I've done with him. There's a builtin understanding between us, and he knows Oliver's tastes. For me, the timer and the lab are the two most important choices for a director of photography."

Despite the seeming complexity of integrating various film stocks, Richardson found himself enjoying the diversity:

"We ended week two with a night shoot. The day should have been easy, but of course, with Oliver nothing really is. His new saying: 'What should be, won't be!’ The color section with Jim interviewing [a witness] was soft and simple. The material was daytime interior. I went with 5248, shot at approximately T4. The nighttime (black-and-white) material, on the other hand, was contrasty, and single-source motivated. We shall see. Black-and-white film — I'm in love with it."

During the New Orleans sequences, Richardson began drawing on his knowledge of film history in crafting the atmosphere:

"Garrison's office: I've preconceived New Orleans as having a quality of light which is a blend between the tropical texture of Alex Webb's photography and the lighting and composition [by cinematographer Robert Krasker, BSC] in The Third Man. Perhaps the 1963 material in New Orleans should take on a cooler look, which could best be described as without red, chalky; we are attempting to do that now with desaturation. The style of camera coverage might be most interesting if it felt motionless, with very few cuts. There could be a sense of loss through the use of frame balance — keeping faces peering into the near side of the frame. Also, try to reduce the number of metallic glints, to create a duller environment, rich in blacks, but without highlights."

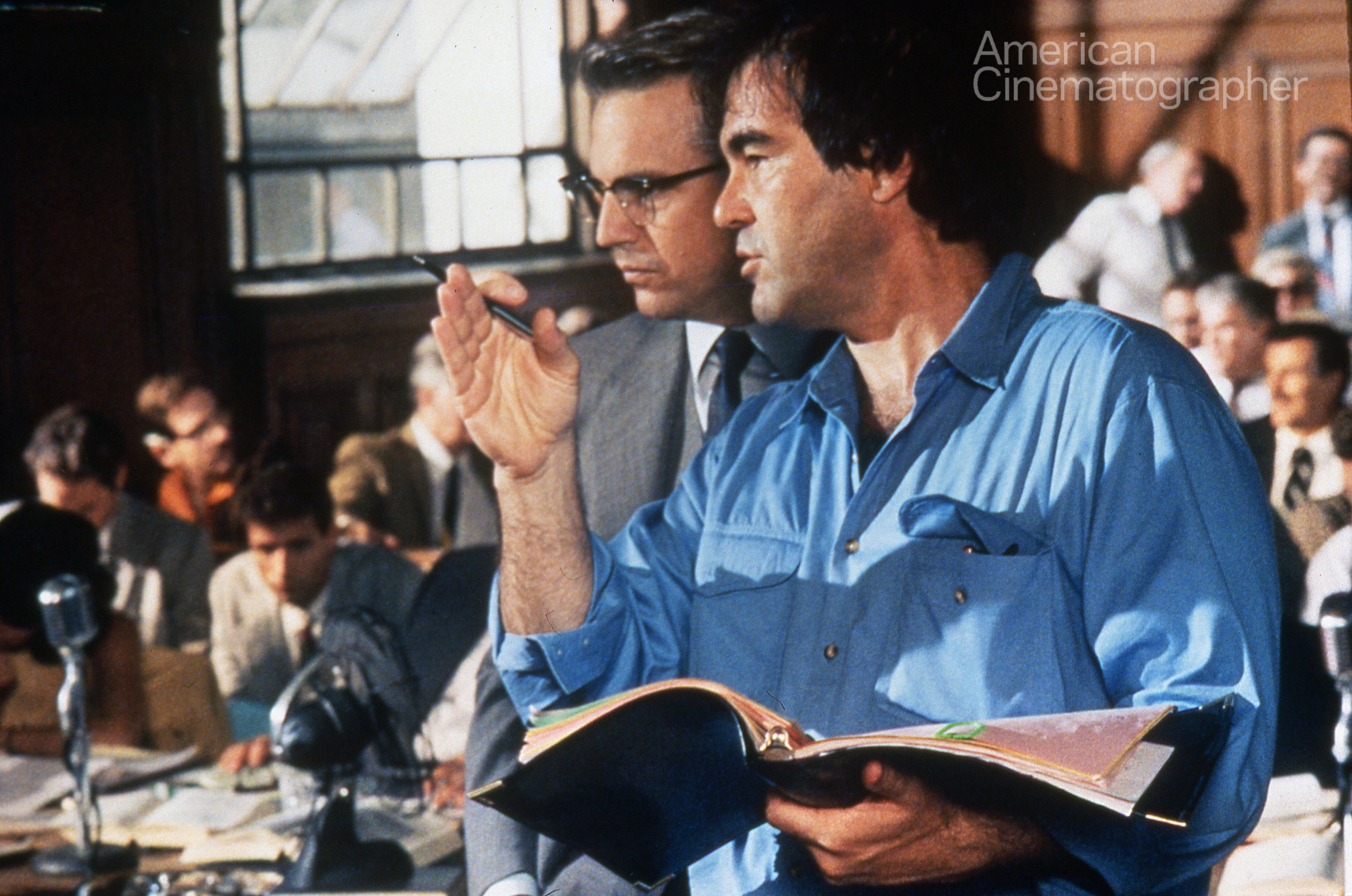

Garrison's offices were staged in a two-story courthouse in New Orleans. "We set up a lot of scaffolds, as though work was being done," he says. "We used that to hang our lights. We lit through windows, so we had natural-looking mixed sources. It was like converting a practical location into a sound stage."

At this point, Richardson wants the audience to feel they are sneaking a look into peoples' private lives at a time of great tragedy and sadness. It's a voyeuristic approach, more like peeping in through a window than actually being in the room.

Large elements of the later photography in JFK are impressionistic. "That was the result of long conversations with Oliver," he says. "There are things which occur outside the normal tangents of conversations between characters. For example, there were subjective flashbacks that illustrated the dialogue. That was incorporated into Oliver's original script, but not in concrete form. That came out of our discussions."

In the middle of a conversation where a character is describing an aspect of the assassination, the scene may cut to Super 8 footage of the shooting, or a brief illustrative clip photographed at three or six frames per second, providing an almost surrealistic insight into someone's memories. Earlier in the film, individual personalities seem almost impenetrable. Faces are masked in shadows, or behind a flag or some other object — visual references to Robert Frank and Ralph Eugene Meatyard. As Garrison's investigation moves forward, he begins to peel away these barriers, digging deeper into personalities. As the point of view becomes more subjective, the audience starts seeing faces and eyes, and what's behind them. Deeper into the script, the story begins to unfold through Garrison's eyes, revealing what he must have felt.

As Garrison pieced together parts of other people's lives and events, he started to believe there was more to the assassination than a random act of violence. Richardson felt himself being similarly drawn into the film. When he looked around one day, he saw it was happening to everyone on the crew: they were all living the story.

That involvement was in part fueled by Stone's directorial style:

"Oliver manages to split everyone into cells. It makes the work more difficult because you are always struggling to get someplace. He feeds on this. It creates an element of creativity that is very high. But it leaves you exhausted at the end of the day."

Stone's methods may be rigorous, but they often lead to movie magic. "Oliver disdains convention. He tries to force you into things that are not classic," Richardson relates. "There's this constant need to stretch, which forces your lighting into very diverse positions. Rarely do you resort to classic lighting modes. More often you do something quite contrary, which inevitably involves risk — and with risk comes failure or success."

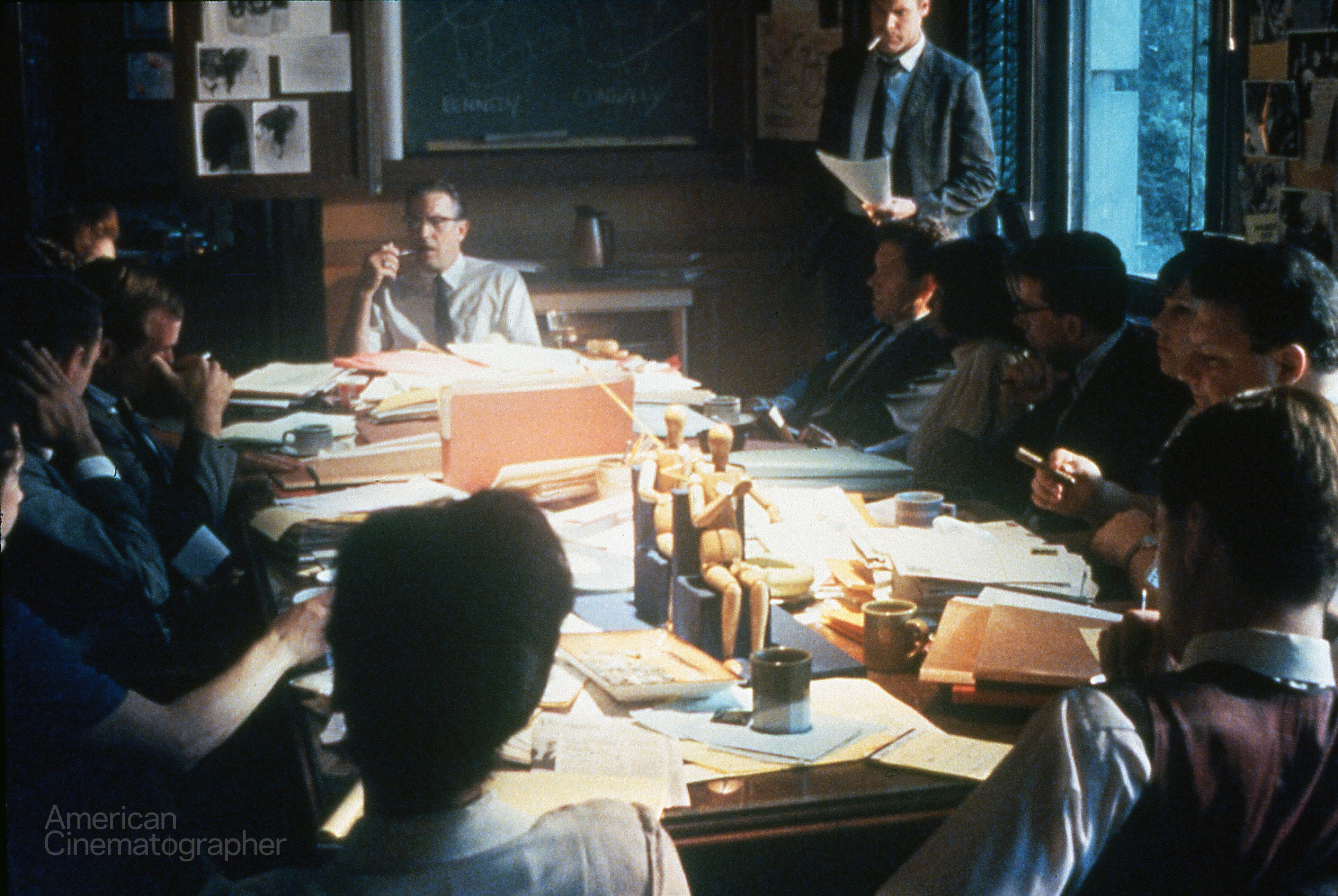

As an example, Richardson singled out a color 35mm scene in which Oswald plots the assassination with his co-conspirators: "Everything in the room played off one table. We took a series of HMI PARS directly overhead and we bounced the key light off the table. Then we had a low, hard light come through the near window. That's our edge light. The faces ranged in exposure from 2/3 overexposed [Oswald], to a stop and 1/2 under for those furthest from the table."

For a black-and-white scene in Dallas, where Kennedy's coffin is waiting to be transferred, Richardson blasted hot white light down from the nine separate tungsten PARs overhead. Ambience from the harsh white illumination reflected off the coffin, providing sufficient light to create moody contrast. The results are heartbreakingly elegiac and will undoubtedly prompt sad memories in many viewers.

Almost all interiors, both day and night, and nearly all night exteriors were recorded on Eastman EXR 5248 film, which Richardson exposed as recommended. "It's a cleaner look," he says. "Maybe no one will notice that but myself and my peers. But I think there's a difference, at least on the best first-run screens."

Richardson used the 50-speed EXR 5245 film for many daylight exteriors. He also employed some of the daylight balanced 250-speed Eastman 5297 film during several interior mixed-light situations. The 500-speed EXR 5296 film was used for several large evening exteriors, such as a scene outside of Garrison's house and for a particularly dimly-lit night interior.

There's a trade-off for using the 100-speed film, especially shooting in the anamorphic format. The lenses are generally slower — though Panavision now does offer some faster Primo lenses — in anamorphic. Richardson worked around this by simply pulling out the bigger guns. "Instead of using a 2K, you put up a bigger unit, like a 9 light or a 10K," he says. "It's just the nature of working with slower films. Of course, having a brilliant focus puller is essential, and Don Carlson certainly fills that bill." As the shoot progressed, Richardson began running into the usual array of challenges:

"Day one of week four was a disaster. We shot the Oval Office and rich men sequences. It was 16 hours of work. The sets are both complicated and diverse. The rich men set was small. Oliver was dissatisfied with his writing so we shot everyone in silhouette. I did my best; we shall see. The Oval Office is circular with curtains on all the windows. Oliver wanted 180 and 240 degrees of coverage in primary scenes. Pure hell. Phil Pfeiffer on second unit is doing a great job despite lack of support."

The last 45 minutes of the film was staged on the third floor of an actual New Orleans courtroom, which featured tall windows and a ceiling that was roughly 30 feet high. Chris Centrella, the key grip, used Condor cranes to bring daylight through the windows at the proper angle and intensity for time of day. The cavernous room provided an opportunity to fill the anamorphic frame with delicious images.

Garrison is in the majority of the scenes. He comes across as a flawed man determined to do the right thing, and his investigation is meticulous. Richardson and gaffer Ray Peschke used light to help the audience see all of Garrison's dimensions. For example, the lighting in his home is softer with warmer hues — more empathetic. "Perhaps I'm sentimental," Richardson says, "but I saw his home as the most stable and least threatening element in Jim's life."

His office is the opposite. Garrison provokes fights, and for these scenes, Richardson used hard-edged light, with additional blue, and he shot for a higher level of contrast.

"Every scene, and each character in it, defines its own look," Richardson says. "Kevin is the star, but we didn't treat him differently. It really came down to the way Oliver staged scenes. Typically, Garrison asks a question that sparks a flashback sequence. Or he's in the courtroom delineating his hypothesis. He's in the center of things. All of our visuals spread from there."

Many sequences incorporate dialogue, such as Garrison questioning witnesses or the Warren Commission meeting. Richardson frequently employed a second camera in those situations. Operated by Phil Pfeiffer, the second camera usually provided isolated coverage of reactions. In scenes involving complicated physical action, Richardson used a single camera, which was usually very active and mobile.

More from the diary:

"As Jim begins his investigation amidst a prevailing spirit of sadness, let's allow an almost funeral type atmosphere to rule. Tones and colors should reproduce in the darkest groups. All colors should appear without red, except act one, which is the documentary section. No primaries (colors) except the accent. As we slide into the beginning of the investigation, a feeling of life just budding should be apparent, Washington in the spring with cherry blossoms, trees in New Orleans with fresh green leaves, a feeling of freshness with things percolating above and below the visual surface. The colors must aid and reinforce hope in the face of adversity which eventually washes away."

Eventually, winter comes; the suits get darker and the colors fade away. Richardson added a level of warmth with gels and color transitions for scenes where he knew there would be flashbacks.

As the project neared completion, Richardson began to reflect on Stone's working methods and artistic progress:

"Over the past two weeks my admiration for Oliver has grown. His eye for actors has expanded. The nuances are superior to all of his previous films. He lets Kevin open and close the door to his soul; it's ice and fire."

While Richardson has certainly demonstrated an ability to do potent work with other directors (John Sayles' City of Hope is just one example), the magic of his collaboration with Stone is that it always unveils something fresh and new. Stone is always pushing Richardson to dig a little deeper and give more of himself to the project. And somehow Richardson finds that there is more to give.

In the end, JFK doesn't give the audience the answers it will be seeking. That's not Stone's way. Instead, it gives them options, and many things to think about long after the last scene has run its course.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.