Without Limits: Robert Richardson, ASC

Our 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award honoree continues to demonstrate an uncontainable spirit of cinematic exploration.

By Patricia Thomson

Photos by Alex Bailey; Sidney Baldwin; Keith Bernstein; Jaap Buitendijk, SMPSP; Phillip Caruso; Andrew Cooper, SMPSP; François Duhamel, SMPSP; Roland Neveu; and Zade Rosenthal. All images courtesy of the AC archives.

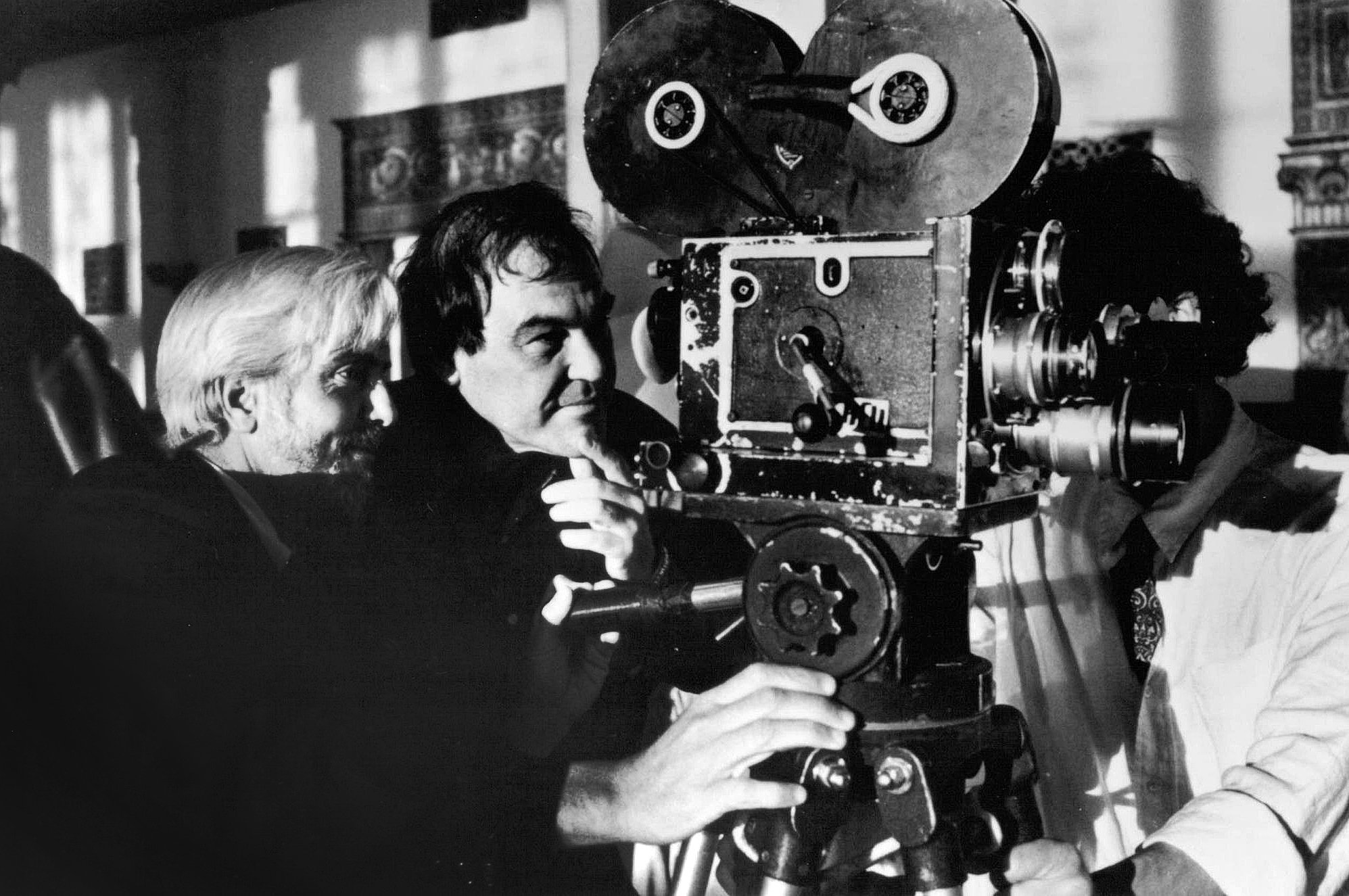

The fact that Robert Richardson, ASC — the recipient of this year’s ASC Lifetime Achievement Award — counts Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC as a big influence is a telling detail. It’s not just Storaro’s expressionistic lighting and mastery of camera moves that Richardson admires. It’s also his collaborative spirit, which led to long and fruitful relationships with such renowned directors as Bernardo Bertolucci, Francis Ford Coppola and Carlos Saura.

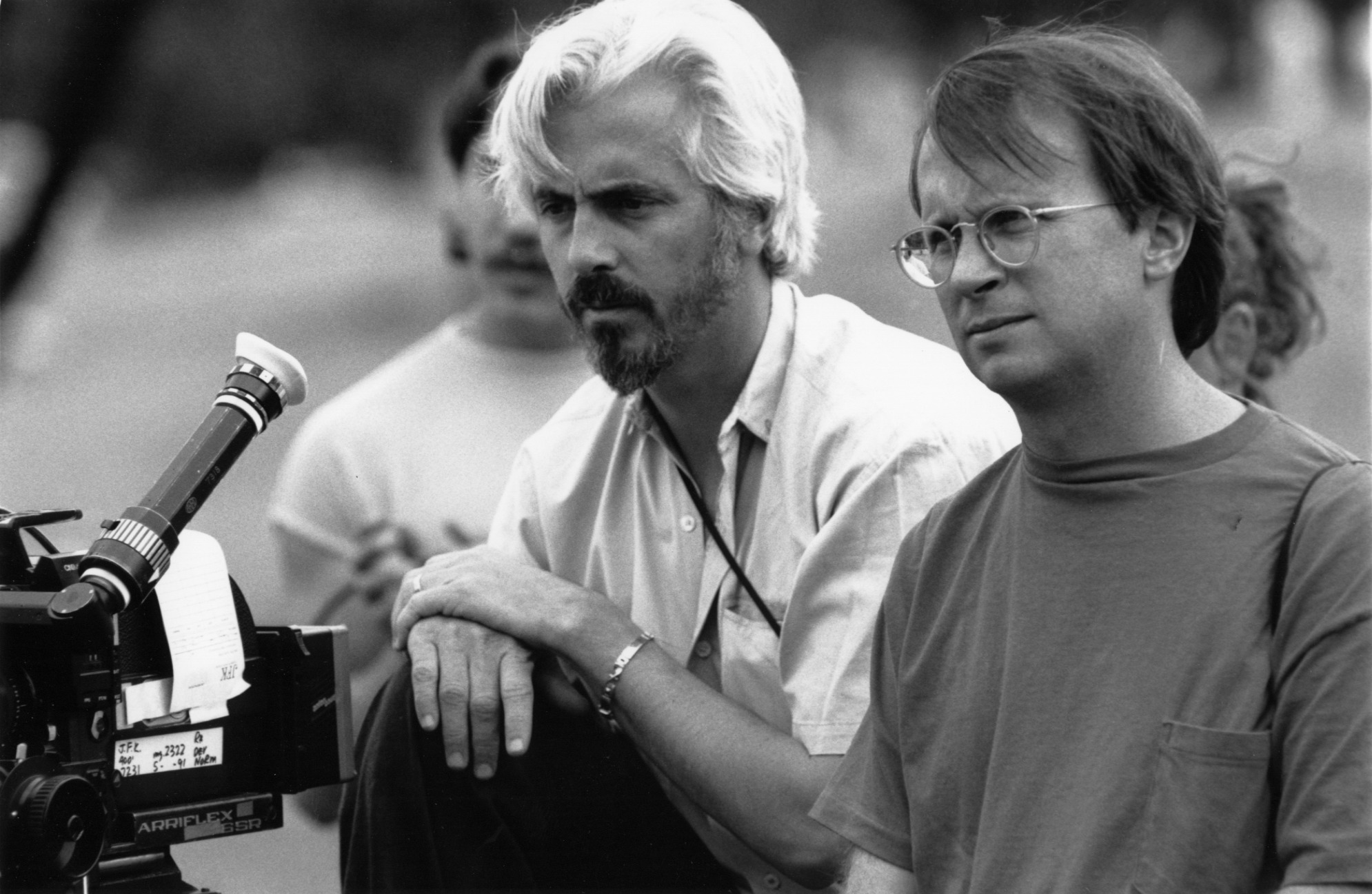

Now, almost 40 years into his career, Richardson occupies a similar position: He’s lauded as a master operator who’s equally adept at expressive lighting, and he’s forged long and fruitful relationships with his own roster of brilliant auteurs, most notably Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino. With Stone, he shot 11 films and got his first Academy Award nomination (Platoon) and first win (JFK). His output with Scorsese includes seven films and two Oscars (The Aviator and Hugo). He just wrapped his sixth opus with Tarantino; the first five racked up three more cinematography nominations from the Academy (Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight). His filmography also includes work with directors Scott Hicks (snagging yet another Oscar nomination, for Snow Falling on Cedars), John Sayles, Barry Levinson, Robert De Niro, Ben Affleck, Robert Redford, and Matthew Heineman, among others.

“Bob doesn’t settle. He doesn’t do a shot just to knock it off the shot list. With Bob, every shot is 100 percent, even if it’s just 36 frames.”

Filmmaker Errol Morris, who’s collaborated with Richardson on three documentaries and various commercials, says, “I sometimes give DPs two grades: a grade for operating and a grade for lighting. Bob gets an A+ for both.” Visual-effects supervisor and 2nd-unit director-cinematographer Rob Legato, ASC says working with Richardson is like playing tennis with a top pro who ups your game tenfold: “The assumption is, if you show up at center court at Wimbledon, you’re expected to play championship tennis.” Richardson’s longtime key grip Chris Centrella observes, “Bob doesn’t settle. He doesn’t do a shot just to knock it off the shot list. With Bob, every shot is 100 percent, even if it’s just 36 frames.”

It took some time, however, for Richardson to find his niche. Born on Cape Cod, where his family owned and operated the Cape Cod Sea Camps, he had a childhood of sun and sea that was mixed with divorce as well as serious ear maladies and repeated hospitalizations. Richardson describes himself and his older brother as “wild children” and “uncontainable.” He was sent to Proctor Academy “for his own good,” he says, and it was there that he discovered photography. But when it came time to declare a major at the University of Vermont, he picked oceanography — “because I was lost,” he tells Jana Hojdová, a Czech director-cinematographer who is preparing a book and documentary on Richardson

“When I met Oliver, I felt there was a magical air about him — as strong a mind and spirit as I’d yet encountered. I believed he could pull anything out of his magic hat. A magician he was. Or a shaman.”

The youth’s salvation came in the form of an Ingmar Bergman series at the university art house. He went from being perplexed about his future to nursing a burning desire to learn everything possible about cinema. “Bergman’s films were cerebral and did not have the flash of commercial films,” he elaborates by email from the set of Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. “Bergman’s work — along with Fellini, Truffaut, Godard, Costa-Gavras, Kurosawa — lifted me away from that which I had tended to watch. Whether dealing with a spiritual issue (Silence), mortality (Wild Strawberries, Seventh Seal), or whatever Bergman deemed to tackle, I was drawn toward his mind. But furthermore, beneath each of his films I felt a current of passion.”

Taking a year off from school, Richardson worked as a theater manager — and purchased his first camera, a Bolex. His first hands-on training came at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he was exposed to an even wider cinematic universe, including the avant-garde works of Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, Man Ray, et al. — a well he later tapped when making such visually textured films as Natural Born Killers (AC Nov. ’94) and Fast, Cheap & Out of Control. “It’s extremely important to expose yourself to a broad range of films, not just while a student but throughout your career,” he insists. Richardson remains a cinephile to the core, possessing a couple thousand DVDs and an unflagging appetite for watching films of every kind.

At the American Film Institute, Richardson had to pick a specialty for his MFA. “I’d fallen in love with seeing the world through a lens, so I chose that path.” His training included internships with Néstor Almendros, ASC on Still of the Night and Bergman cinematographer Sven Nykvist, ASC on Cannery Row. “Both Néstor and Sven were amazing to watch work,” he recalls. “My relationship with both was meager; I was far to the side, and they were barely aware of my existence. That said, their work is an inspiration of the deepest magnitude.”

Important connections were forged at AFI. First and foremost was Centrella, who gave Richardson his first post-grad job as director of photography. The film was a documentary Centrella was producing: Desperate Dreams (1982), about the Western States Endurance Run, a 100-mile ultramarathon in Northern California. Coverage required Richardson to leapfrog the runners six times over the course of 24 hours, often on inaccessible roads. “That was definitely Bob’s M.O.,” says Centrella. “Bob has boundless energy and an amazing amount of endurance.”

“To work side by side with Chris for over 30 years is one of the happiest of relationships I’ve found in this business,” Richardson adds. “Alongside Chris is my relationship with both [gaffer] Ian Kincaid and [camera assistant] Gregor Tavenner — lifelong creative relationships, and masters all.”

After graduation, Richardson suffered through long stretches of phone silence and filled the empty hours watching films, but felt himself “rusting away.”

He caught a break when a former AFI classmate gave his name to documentary producer-director Jeff B. Harmon, who was prepping The Front Line (1982). The project would intertwine opposing sides in El Salvador’s civil war, and Harmon needed a cinematographer to follow the military death squads. During his interview, Richardson was asked whether he’d been to war before and whether he could shoot under fire, and was informed he’d need a bulletproof vest. “The experience was life-changing,” attests Richardson, who did indeed come under fire multiple times. Nonetheless, “that experience cemented my deep love and need for filming.”

Richardson subsequently got a taste of feature-film magic and some industry credibility doing pickup shots on Alex Cox’s Repo Man and 2nd-unit work on Making the Grade, directed by his AFI buddy Dorian Walker.

Then came a stroke of “monumental good luck,” according to Richardson. Oliver Stone was crewing up Salvador (1986), about a photojournalist caught in the middle of the civil war. Stone was looking for a handheld style of photography, and two AFI alums recommended Richardson. Stone felt the cinematographer’s work on The Front Line had the right stuff. Plus, “I liked him,” says the director. “I liked his attitude. He was raw. He was volatile. He was interesting. We got along very well.”

“When I met Oliver, I felt there was a magical air about him — as strong a mind and spirit as I’d yet encountered. I believed he could pull anything out of his magic hat. A magician he was. Or a shaman,” Richardson recounts to Hojdová. “I recognized immediately that I was not going to shoot what would be called a ‘beautiful’ film. I let go and absorbed the harsh conditions. Made the shadows characters. Made the grit characters. Bring on the grain.”

“Bob would line up a series of cameras in a row, fully loaded — from Super 8 to 35mm. He’d shoot one camera, then pick up another and shoot that camera, then pick up a third and keep shooting.”

By the time production wrapped, Stone had invited Richardson to shoot his next film, a deeply personal project about Vietnam called Platoon (1986). Production in the hot, humid Philippine jungle was as grueling as any boot camp. “Oliver did not believe in bending if a location was too far or difficult to get to — Herzog in that way,” the cinematographer tells AC. “But by doing this, we all bonded. Actors would help the crew carry gear when they could, and Oliver created a small army devoted to his vision.” It helped that the film was largely shot in sequence, and that whenever a character was killed, that actor would exit the production, leaving an increasingly small band of brothers.

After Platoon brought home four Oscars — for Best Picture, Director, Sound, and Editing — Stone’s and Richardson’s reputations skyrocketed in tandem. They rode the wave, completing a rapid succession of films, including Wall Street (1987), Talk Radio (1988), Born on the Fourth of July (AC Feb. ’90) and The Doors (1991).

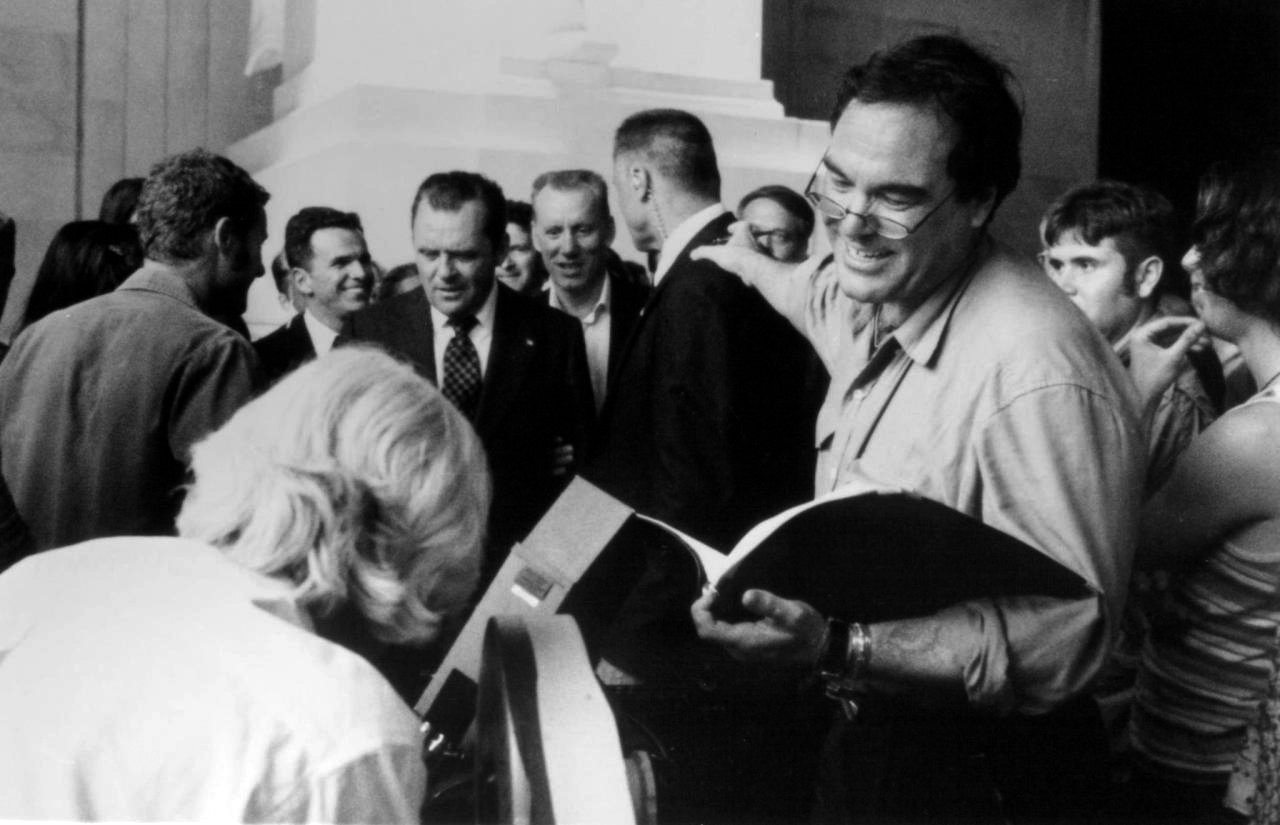

It was their collaboration on the political thriller JFK (AC Feb. ’92) — with its multitude of formats, film stocks and visual textures — that made the deepest impression on Legato. “It was like, ‘Holy smoke! Who is this guy Bob Richardson?’ I think the ‘Bob style’ started here, the A++ Bob. You notice his work from that moment on.”

As striking for its visual complexity as for its hotly debated conspiracy theory, JFK is a tapestry of formats. “That was driven by the core of the assassination: the 8mm Zapruder film,” Richardson says. “We slowly took hold of that film and moved outside to evaluate how to incorporate the remainder of formats.”

Written as a “jigsaw” and “a fragmentation of reality,” says Stone, the script follows New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) as he peels back the layers of the official line about Kennedy’s assassination and discovers competing versions of the truth. Stone wanted the visuals to be equally fractured — “anything that would dent the narrative,” he says. Black-and-white 16mm and 35mm re-create events on Dealey Plaza and in government back rooms; shots on 8mm color echo the Zapruder film; video, archival footage, and news photographs come into play, plus different styles of shooting.

“Bob had a documentary background, which we used a lot in Salvador, but we’d refined it by the time we got to JFK,” says Stone. “The suggestions for all the visual stocks and things to make it more fragmented, a lot of that came from Bob and from the editors. It was a hectic shoot, very hectic. In Dealey Plaza, where we opened the film, we had about 16 cameras at one point. It was a massive assemblage of footage and different stocks even there.”

“Marty got used to coming up with the bones of the shot, then had Bob fill in the blanks and turn it into art. On the Bob and Marty movies, the combo artistry is at a very high level.”

A few years later, Errol Morris also tapped Richardson’s dexterity with formats and emulsions. The film was Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997), which interlaced profiles of a lion tamer, a robotics scientist, a mole-rat specialist, and a topiary gardener. “We shot straight 8, Super 8, 16mm, Super 16, 35mm, 35mm step-printed, black-and-white, infrared color, infrared black-and-white — on and on, the kitchen sink of film stocks and cameras,” Morris says. “We’d be shooting the Clyde Beatty Cole Bros. Circus, and Bob would line up a series of cameras in a row, fully loaded — from Super 8 to 35mm. He’d shoot one camera, then pick up another and shoot that camera, then pick up a third and keep shooting. He would have a way with each camera, each format, each emulsion, of creating unique images. Extraordinary images. Who else could really have done that?”

Meanwhile, Richardson and Stone completed another four films together, and during their 11-year collaboration, Stone watched Richardson mature. “How does a cinematographer grow? He’s able to take more risks, he’s able to judge the outcomes easier, faster, with fewer mistakes. By the time we did U Turn [AC Oct. ’97], he was shooting reversal stock, which is risky. We had to get a waiver from the insurance company; there was no protection, no net,” Stone says. “So in other words, Bob became more confident and became who he is.”

For his part, Richardson regards Stone as an older brother who took him under his wing during his formative years. And the director passed on an ethos that Richardson still holds dear: Preparation is fundamental. “Oliver really researched his films’ subjects, and that gave him a magnificent control over the material,” the cinematographer says. “That was and is one of the great lessons I took from Oliver: Research cannot be underestimated, whether in the form of reading material or visual/audio. There can be no limit.”

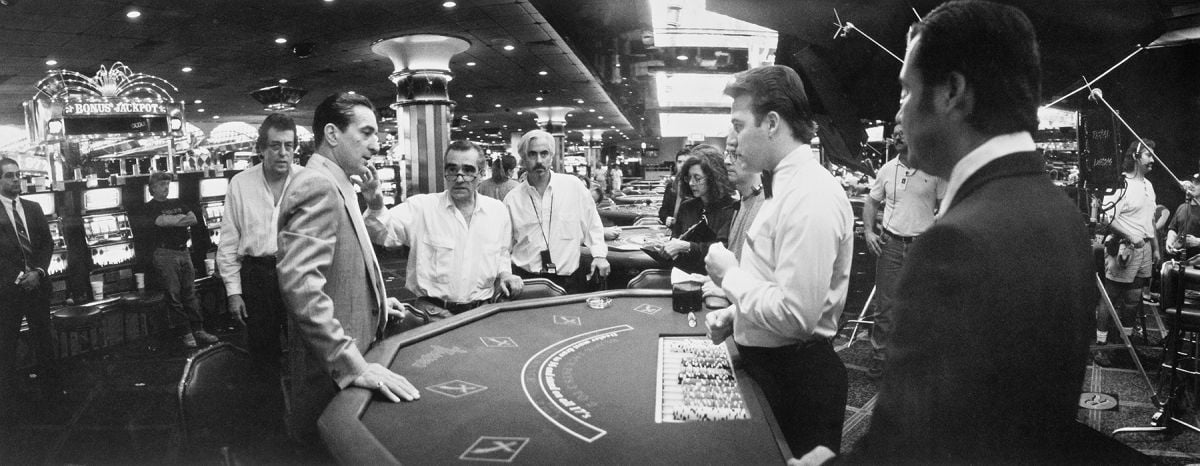

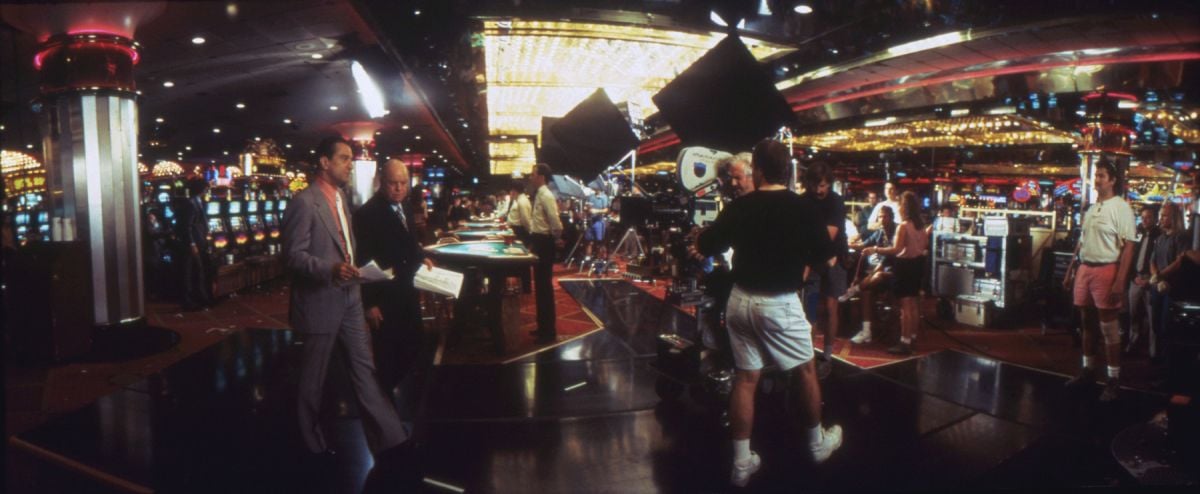

A new chapter began with Casino (AC Nov. ’95), the cinematographer’s first collaboration with Scorsese. They’d met years earlier for an interview that was “beyond daunting,” according to Richardson. The subject was Cape Fear. No script was available, but Richardson knew the 1962 version with Robert Mitchum. He brought some atmospheric photographs by Kentuckian Ralph Eugene Meatyard, which he felt suggested “ghosts that reeked of something rotten, shifting in a slow, hot Southern wind,” as he told Hojdová. Scorsese was polite but said he wanted hard lights and deep contrast, and had already decided on Freddie Francis, BSC as director of photography.

Four years after that meeting, Richardson was hired for Casino, his first Super 35 feature. Depicting the final days of the Chicago mob in Vegas, the film was the culmination of Scorsese’s gangster trilogy, which started with Mean Streets and Goodfellas, then progressed to the Vegas wiseguys at the height of their power, before they self-immolated from greed. Casino involved a much larger canvas, with more than 289 scenes and six weeks of filming inside a working casino. Taking the classic crime movies shot by John Alton as their inspiration, the team updated that noir look with flashy saturated colors, swish pans, fast dolly moves, and bravura camerawork worthy of the story’s 1970s and ’80s world of excess.

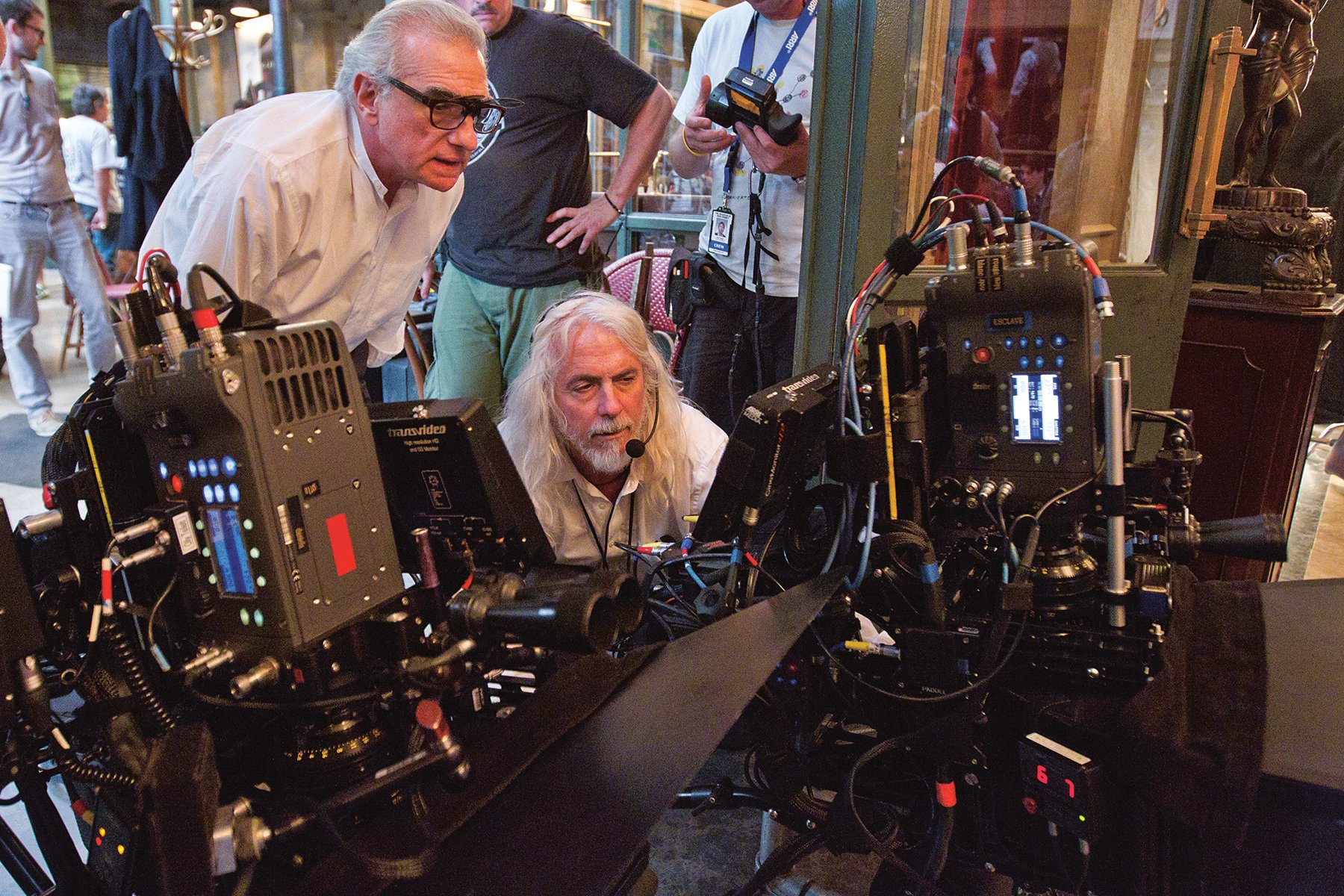

After their scout, Scorsese vanished to finish the script. Richardson made use of his time by drawing up a shot list. But upon presenting some pages to Scorsese, he learned he was dealing with a different type of director. Scorsese designed the shots, period. Richardson would stick to lighting and operating.

“Marty doesn’t really want to hear your version of the shot, because it may unduly alter or influence the storyboarding of the sequence created in his imagination,” explains Legato, a veteran of eight Scorsese projects. But about halfway through Casino’s production — and increasingly as the years rolled by — Scorsese became more open to Richardson’s refining his shots and adjusting their choreography. “They had a pretty great relationship,” Legato observes. “Marty got used to coming up with the bones of the shot, then had Bob fill in the blanks and turn it into art. On the Bob and Marty movies, the combo artistry is at a very high level.”

“On more than one occasion, Bob has said, ‘You don’t want the shot to suffer just because of geography.’ You do the better shot if it still drives the movie forward.”

Clearly the Academy thought so on The Aviator and Hugo. In addition to their art, both films involved a high degree of technical prowess to achieve their looks. The Aviator (AC Jan. ’05) replicated 2-strip and 3-strip Technicolor, while Hugo (AC Dec. ’11) merged the palette of early 20th-century autochromes with 3D filmmaking done the classic way, using dual cameras on set rather than a conversion in post. What’s more, Hugo’s cameras were prototypes of Arri’s Alexa, making it both Richardson’s and Scorsese’s first digital feature.

The cinematographer has always been open to new technologies and what they offer. “One must be in an industry and a world where there are constant shifts, whether at a molecular or cellular level, or social, or whether in our craft with lighting, digital capture, lensing, etc.,” he says. “I believe in blending the best of the past, present and future.”

Throughout it all, Richardson developed his own approach to lighting. Many observers consider his signature touch to be a high top- and backlight, which might blow out the rim, bounce off tabletops, or accent the space — or set a topiary giraffe on fire, as happened on Fast, Cheap & Out of Control — though Richardson has dialed this back in recent years. Another preference: large, soft sources controlled with layers of muslin, especially to get the facial tones right. “He’s a believer in big sources a little farther away so the falloff is more natural,” Centrella notes.

Most importantly, Richardson isn’t afraid to ignore the conventional “rules” of lighting if doing so will result in a better shot. That includes the rulebook on motivated lighting. If he needs to change the direction of the key light within a scene, or backlight both characters in a shot-reverse-shot, so be it. “On more than one occasion, Bob has said, ‘You don’t want the shot to suffer just because of geography,’” says Centrella. “You do the better shot if it still drives the movie forward.”

“That was a big eye-opener,” says Legato, “that freedom of expression to ‘make every shot look great.’ Once you do it, it’s very hard to get off of it. It’s like a drug. You get used to doing your very best.”

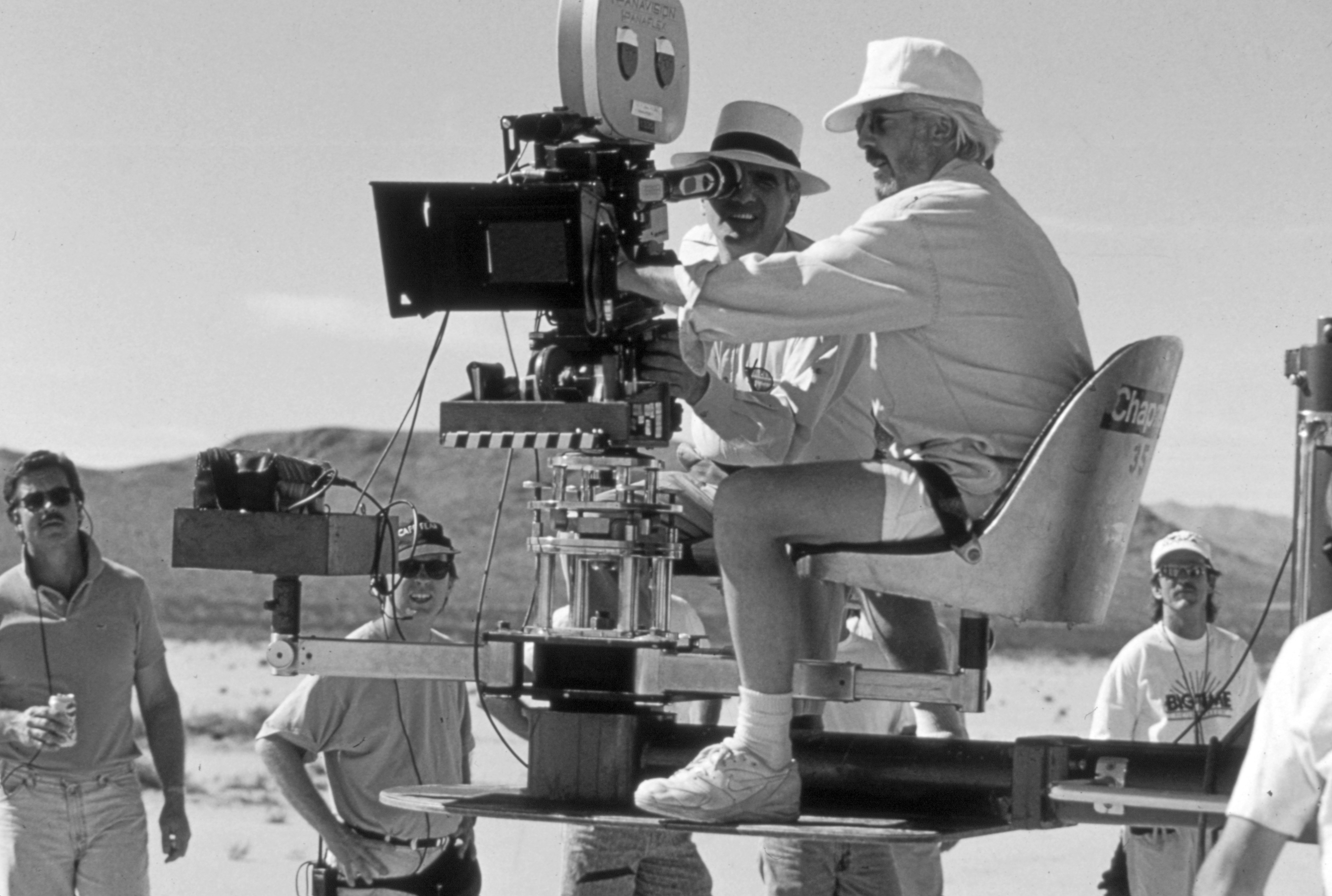

Richardson routinely operates camera, whether he has to hire an operator or not. On crane shots, he prefers to ride a manual crane with a fluid head, the better to connect with actors and action through the lens.

Morris identifies another Richardson trait: “Bob is the only cameraman I’ve worked with who would actually edit in camera,” he says. “You could take a strip of Super 16 he had shot, all handheld, that might contain a hundred images. All of them could be used without having to cut them at all; they’d been pre-edited in camera. That is amazing.”

Legato recalls a related experience on 2nd unit for The Good Shepherd (AC Jan. ’07). “We did a dolly shot, and I needed a few feet to get up to speed; then the extras filled in and that became the shot.” Legato thought the result looked pretty good. Richardson didn’t. “‘What did you shoot that for?’” Legato recalls him saying. “‘Well, this part of the shot is good.’ ‘Yeah, but the rest isn’t. And they may use it.’ I said, ‘What would you have me do?’ He said, ‘Don’t turn on the camera during that part, because if they don’t have it, they can’t use it. Start the dolly, then turn on the camera.’ That stuck with me. So whenever I shot anything, I made sure the meat of the shot was the only thing photographed — because they might use the other part.”

“I was exhilarated at the incredible vibrancy and detail of the images. It was a revelation. All previous films shot on 35mm now reminded me of either 16mm blown up to 35mm, or Super 8.”

Richardson’s specificity syncs well with the production style of Quentin Tarantino, who’s often quoted as saying, “I don’t select, I direct.” The two began their journey together in 2002, with the 155-day shoot that became the two-part revenge flick Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (AC Oct. ’03) and Vol. 2. Shot on Super 35mm with heavy use of Tarantino’s beloved zooms, Richardson’s cinematography pays homage to action films from East and West: kick-ass kung fu, samurai sword fests, operatic Spaghetti Westerns, black-and-white noir, and more.

Like Scorsese, Tarantino has an encyclopedic knowledge of film, which the Kill Bill mash-ups fully exploit. As Centrella has observed, “Marty and Quentin know shots from movies literally 30 years ago and say, ‘We want that part of that shot.’ And Bob’s knowledge of film is enough that he can achieve it.”

After reteaming on the features Inglourious Basterds (AC Sept. ’09) and Django Unchained (AC Jan. ’13), Richardson and Tarantino took a giant leap of faith with The Hateful Eight (AC Dec. ’15), for which they resurrected Ultra Panavision 70 for the first time in almost 50 years. Their original idea was to shoot the snowy Western in standard 65mm, but while sniffing around a back room at Panavision, Richardson spotted the old lenses in a dark corner. Those Ultra Panavision lenses, last used on 1966’s Khartoum, set The Hateful Eight on a new course, one that ended up with 70mm projection prints. This endeavor required Panavision to refurbish 15 lenses, retrofit cameras, create 2,000' mags for 65mm, and ensure the gear would hold up in the Rockies’ freezing temperatures. Richardson made the super-wide 2.76:1 format work for everything: vast landscapes, actor close-ups, inserts, and the two-thirds of the film set inside a stagecoach post.

“The first time I viewed our test footage,” Richardson recalls, “I was exhilarated at the incredible vibrancy and detail of the images. It was a revelation. All previous films shot on 35mm now reminded me of either 16mm blown up to 35mm, or Super 8.”

Select audiences were able to see the film print in all its glory, no digital intermediate intervening, as a special “roadshow” was arranged for 100-some theaters, complete with printed programs, intermission, projectors and the 70mm prints. “That both frightened me and gave me great pleasure,” Richardson says.

Today, Richardson’s energy is as high as ever. Looking ahead, “There are many technologies I would like to step into,” he says. “To create a film in the manner that Caleb [Deschanel, ASC] and Rob Legato just completed with The Lion King is one example of a technology I’d love to work with. HFR [high frame rate] is another. I see no end to what I’d be willing to explore.”

Richardson being presented with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award by Quentin Tarantino:

You'll find our complete coverage on the 33rd Annual ASC Awards for Outstanding Cinematography ceremony here.