Shooting Motion-Picture Negative With a Still Camera

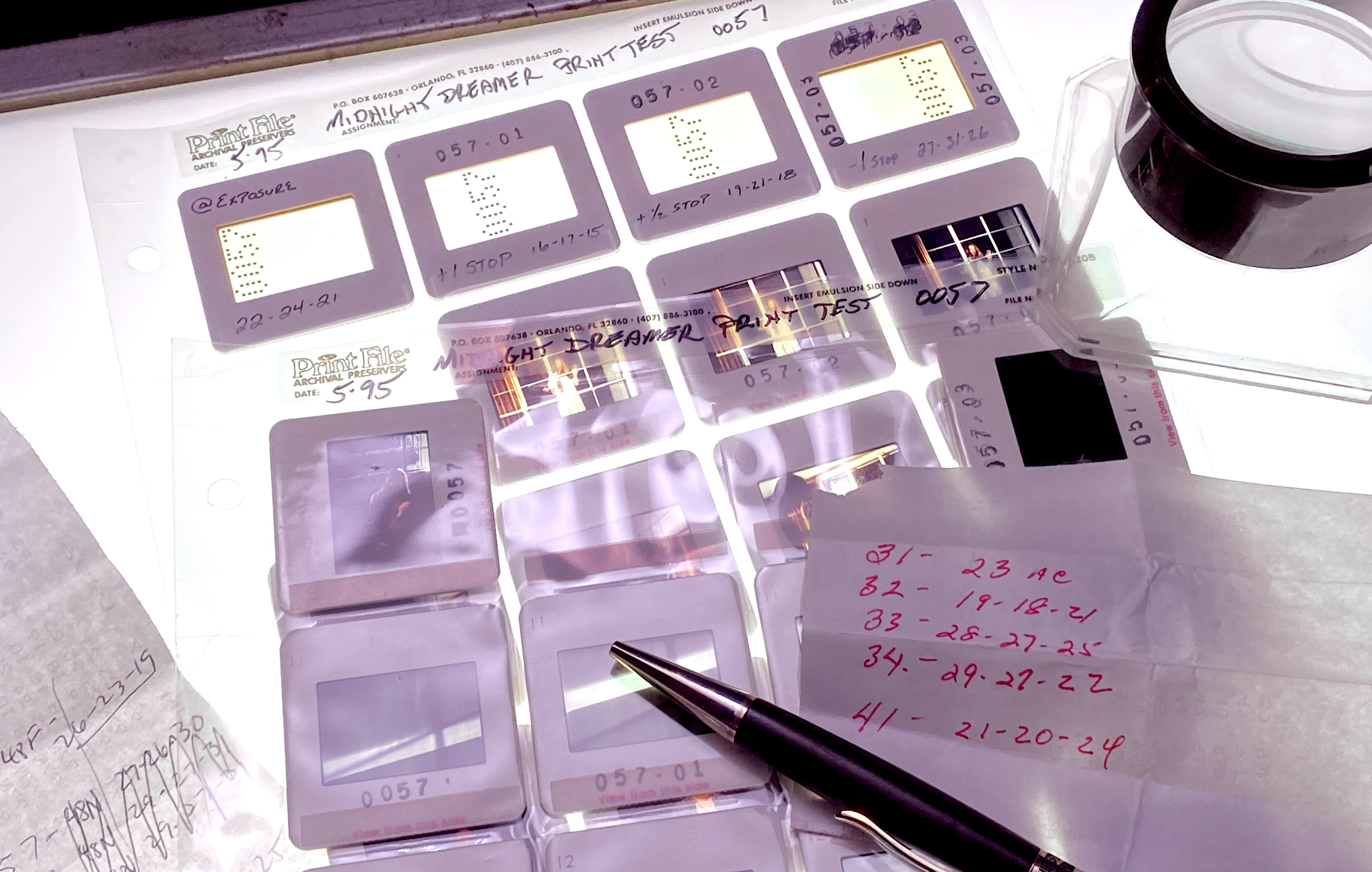

One can learn film emulsions and traditional printer lights by printing several versions of positive-print slides at various densities.

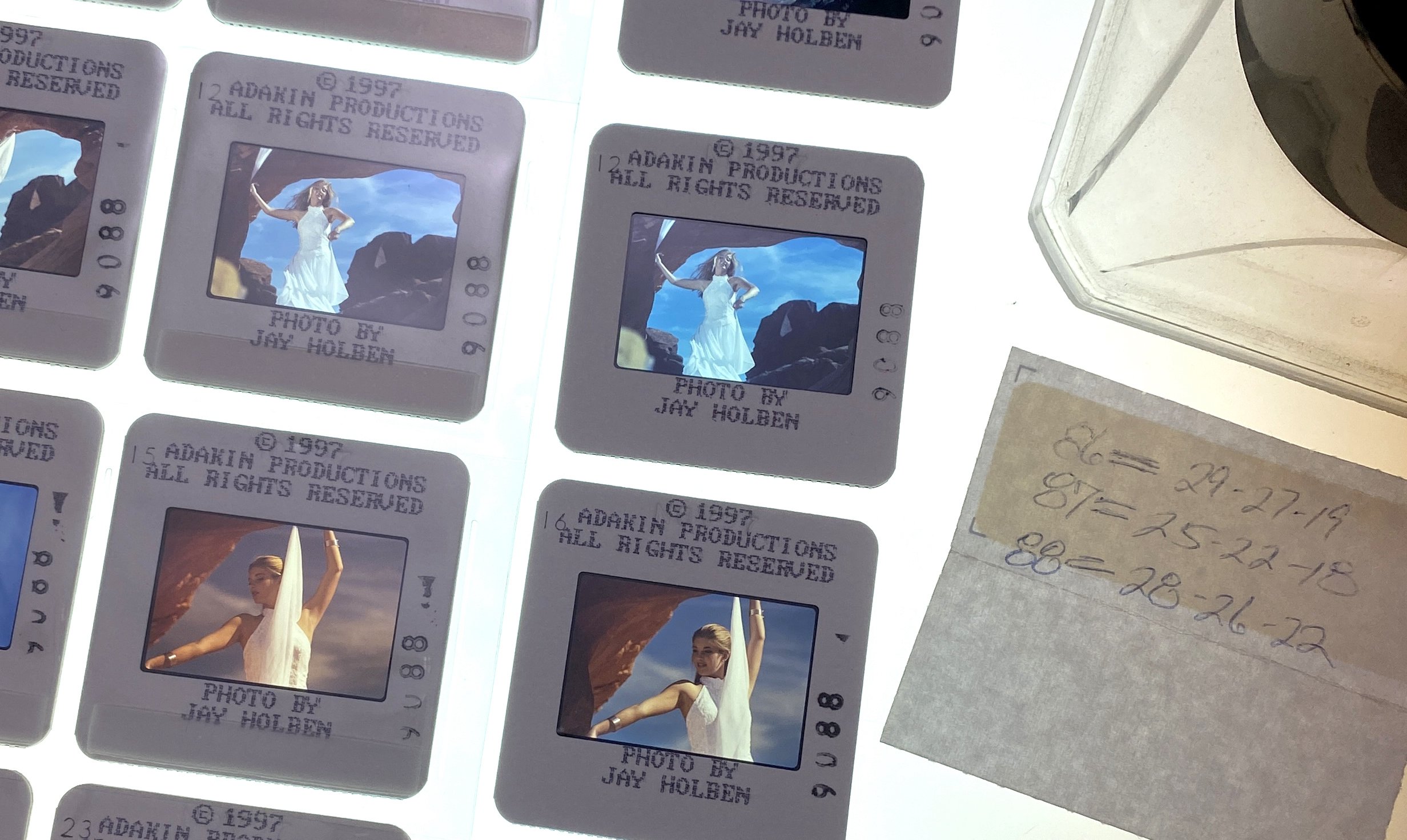

Photos courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

There’s no substitute for practical experience, and back in the pre-digital era, it was a significant challenge to get a 16mm or 35mm camera package to experiment with exposure and learn the sensitivities and characteristics of each available film stock. Further, it was prohibitively expensive to buy the film and then get it processed in a lab, especially when I was living in Phoenix, Ariz. So, when the concept of shooting moving-image film with still cameras came to my attention, it was quite a revelation.

RGB to the Rescue

RGB Color Lab in Los Angeles was a small company on Highland Avenue run by William and Nadine Beale, and they sold Eastman Kodak motion-picture stock rolled into 35mm-still-film canisters (135 format). From Arizona, I could mail-order rolls of the latest film stocks, shoot them in a still camera and send the exposed rolls back to RGB, which would develop them and print slides.

This was a game-changer. I couldn’t afford to obtain an Arriflex or an Aaton to test film, but I absolutely could order film negative and take test photos (almost) to my heart’s content. Further, RGB allowed the opportunity to dictate printer lights (before digital scanning was prevalent), which allowed for advanced experiments and achieving the same experience of making a film print in the lab. (This may sound strange to younger cinematographers, but before there was digital projection, film prints for theaters were color-corrected on a Hazeltine, using a system based on values of red, green and blue called “printer lights.”)

So, when it came time to actually film a 35mm motion picture, I was more than prepared.

This process didn’t stop when I became a cinematographer. On a production, the ACs would save the “waste” film (unexposed film of less than 50'), which could be hand-rolled into 135-format still canisters. While film cameras running at 24 fps expose 90' of 35mm film per minute, a 36-exposure still canister of the same 35mm film is only 5.5' long — so 50' of what would otherwise be trash could become eight to nine still rolls.

In its heyday, RGB Color Lab was processing 6,000-8,000 slides per day. Sadly, RGB closed in the early 2000s. There were other companies offering a similar service, but by the early 2010s, they too were all gone.

Still vs. Motion-Picture Stock Processing

Several factors can complicate the efforts to shoot motion-picture film stock with a still camera, and they all stem from how motion-picture and still film are respectively processed. While you might think it is possible to take any motion-picture film to any film lab (or even a local pharmacy) for processing — or, for that matter, take the still canisters loaded with movie film to any motion-picture lab — you’d be wrong, as the processes for developing motion-picture film and still film are quite different.

Motion-picture negative is unique among film types for multiple reasons. Pioneered by Eastman Kodak in 1889, roll-film emulsion evolved significantly over a century to become the pinnacle of analog image capture. Designed for the motion-picture workflow, it was not optimized for paper prints — rather, it was designed to be malleable in color correction to facilitate an interpositive (created from the original negative), an internegative (created from the interpositive) and a release print (created from the internegative). The color science was crafted to be subdued — somewhat like today’s log digital image — to take full advantage of the abilities of the negative-and-print combination.

Thanks to a reinvigorated interest in shooting on film, there has been a resurgence of independent labs that will work with 135-format canisters of motion-picture stock.

Originally, as this film moved through a motion-picture camera at 16 fps (or more), there was a problem with static electricity building up inside the camera from the celluloid running against the pressure plate. This buildup of static could discharge in a spark, leaving spiderweb-like ghost images on the negative. To solve this, a carbon-polymer backing called “rem-jet” was applied to the film emulsion on the back side (which runs against the pressure plate in the camera) to create a slick surface, eliminating static buildup. Rem-jet has a secondary effect, in that it eliminates light reflection off the camera’s highly polished pressure plate, which passes back through the film; this secondary exposure results in halation effects on bright highlights.

The rem-jet backing requires motion-picture film to be processed in a unique way, wherein the backing must first be stripped off in a pre-bath before developing. This yields a sludge of dissolved rem-jet carbon. As still labs are not typically designed for this additional step, if the process were attempted in one, the residue could contaminate the development chemicals and even harm the processing machinery. There are also a number of other complicated steps in the processing of motion-picture film that aren’t involved in developing standard still film. Kodak called this process ECN-2 (Eastman Color Negative 2 — the second iteration of their chemical process introduced in the mid-1970s). The ECN-2 process was specifically designed to produce lower contrast and color saturation in the image — properties that are optimal for photochemical finishing. Color still film, on the other hand, is developed with a more simplified process identified as C-41, which uses different chemicals and fewer steps in its developing path. (See section “A Second Life,” page 14, for more on when to develop motion-picture-film stills with ECN-2 vs. C-41.)

Furthermore, the labs created to process motion-picture film are designed to develop thousands of feet of film simultaneously in long strips through a complicated series of specially designed chemical chambers. Putting 5.5' rolls through these machines would require manually splicing the film together to create long strips — which is not only labor-intensive, but would also require hundreds of these smaller rolls to process simultaneously. A single breakage could then ruin an entire batch of film. It’s not a process undertaken by many labs.

A Second Life

Thanks to a reinvigorated interest in shooting on film, there has been a resurgence of independent labs that will work with 135-format canisters of motion-picture stock.

As did RGB Color Lab, Dunwoody Photo in Dunwoody, Ga., has created an infrastructure to develop ECN-2 negative in the traditional chemical bath for 135-format rolls.

Collaborating with Dunwoody, Atlanta Film Co. sells Kodak Vision3 stocks hand-rolled into 35mm film canisters in 50D, 250D, 500T, and even Double-X black-and-white. You can buy the film through Atlanta Film Co., process through Dunwoody and then have your negative scanned.

Bellows Film Lab in Miami, Fla., and Chicago, Ill., and Andrew’s Analog Service Center, a home-based business in Pennsylvania, will also develop true ECN-2 film and scan it for you.

Though C-41 chemicals can develop motion-picture negative, this bath — as opposed to the ECN-2 bath — results in a denser negative that has more contrast and color saturation. This technique is called “cross-processing.” When cross-processed stock is put through interpositive, internegative and release print, the result is an image with super-saturated colors and very high contrast. (Cross-processing has been a creative choice for some filmmakers seeking to create a unique look through the photochemical process.) It’s important to note that cross-processing produces a “normal” still-film image straight out of the bath, which is ideal for printing and scanning. Therefore, if one’s goal is to become familiar with the film stocks to apply to the motion-picture workflow — for which scanning and post is different from that of still photography — then you need ECN-2. But if you’re shooting ECN-2 for stills, then you want C-41 processing.

Several labs process small-roll ECN-2 in C-41 by conducting their own pre-bath rem-jet removal before they process the film. These include Blue Moon Camera & Machine in Portland, Ore.; Old School Photo Lab in Dover, N.H.; and Boutique Film Lab in Mount Juliet, Tenn.

Several of these companies also offer different sizes of negatives, including 120 (65mm film negative cut down to 61.5mm small rolls), which allows for experimentation in the medium-format world.

At last, you can once again explore motion-picture stocks on a much lower budget! Shoot test shots or location scouts, or just expand your still-photo repertoire with motion-picture emulsions.

While film cameras running at 24 fps expose 90' of 35mm film per minute, a 36-exposure still canister of the same 35mm film is only 5.5' long — so 50' of what would otherwise be trash could become eight to nine still rolls.

Processing at Home

Perhaps even more exciting: Some companies have devised an in-home development process for ECN-2, so you can do it yourself. They have simplified the process so it doesn’t contain the dangerous chemicals associated with traditional ECN-2 large-batch processing, and it takes just a few steps. For example, Flic Film in Longview, Alberta, Canada, provides a home kit that is available from retailers including B&H Photo Video, Freestyle Photo & Imaging Supplies, and Hunt’s Photo & Video.

Taking a different approach, Los Angeles-based siblings Brandon and Brian Wright of CineStill Film work closely with Eastman Kodak to provide specially altered motion-picture stock that has had the rem-jet removed and is optimized for developing in C-41. (It’s not just repackaged motion-picture stock.) They provide 50D, 400D and 800T options that can be developed anywhere C-41 is processed and still retain the qualities of the motion-picture negative. Alternatively, they also sell simplified at-home kits for their film — or for standard C-41 still stock — called Cs41, as well as their own Cs2 chemicals, which can provide an ECN-2-like development process for motion-picture stock you’ve rolled yourself or purchased elsewhere. This results in the “proper” development of motion-picture stock — yielding the traditional lower contrast and color saturation.

DIY Rem-Jet Removal

Interestingly, it’s not hard to remove rem-jet from the back of motion-picture stock yourself — it just takes a high-pH and high-salt-content pre-bath.

Mix 2.5 tablespoons of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) with 1 liter of 100°F water in your developing canister, agitate vigorously for 30 seconds, wait 30 seconds, agitate vigorously for another 30 seconds, and then pour out and dispose of the dark-gray water. Rinse and agitate until the water you pour out is clear. The rem-jet is now gone, and you can process your film either with a C-41 or ECN-2 bath — depending on what you’re aiming to learn!

The author thanks cinematographer and Sigma cine account specialist Francisco Ramirez and the Studio C-41 blog and podcast for their substantial research assistance.

Jay Holben is an ASC associate member and AC’s technical editor. He is also the co-author of The Cine Lens Manual and co-chair of the MITC Lens Committee.