Aspect Ratios for Home Exhibition

Setting the story within a particular frame imparts emotion and key information to the audience.

The composition of the image is a principal component of both visual storytelling and a filmmaker’s aesthetic. Setting the story within a particular frame imparts emotion and key information to the audience, and intrinsic to composition is the shape of the frame — the aspect ratio.

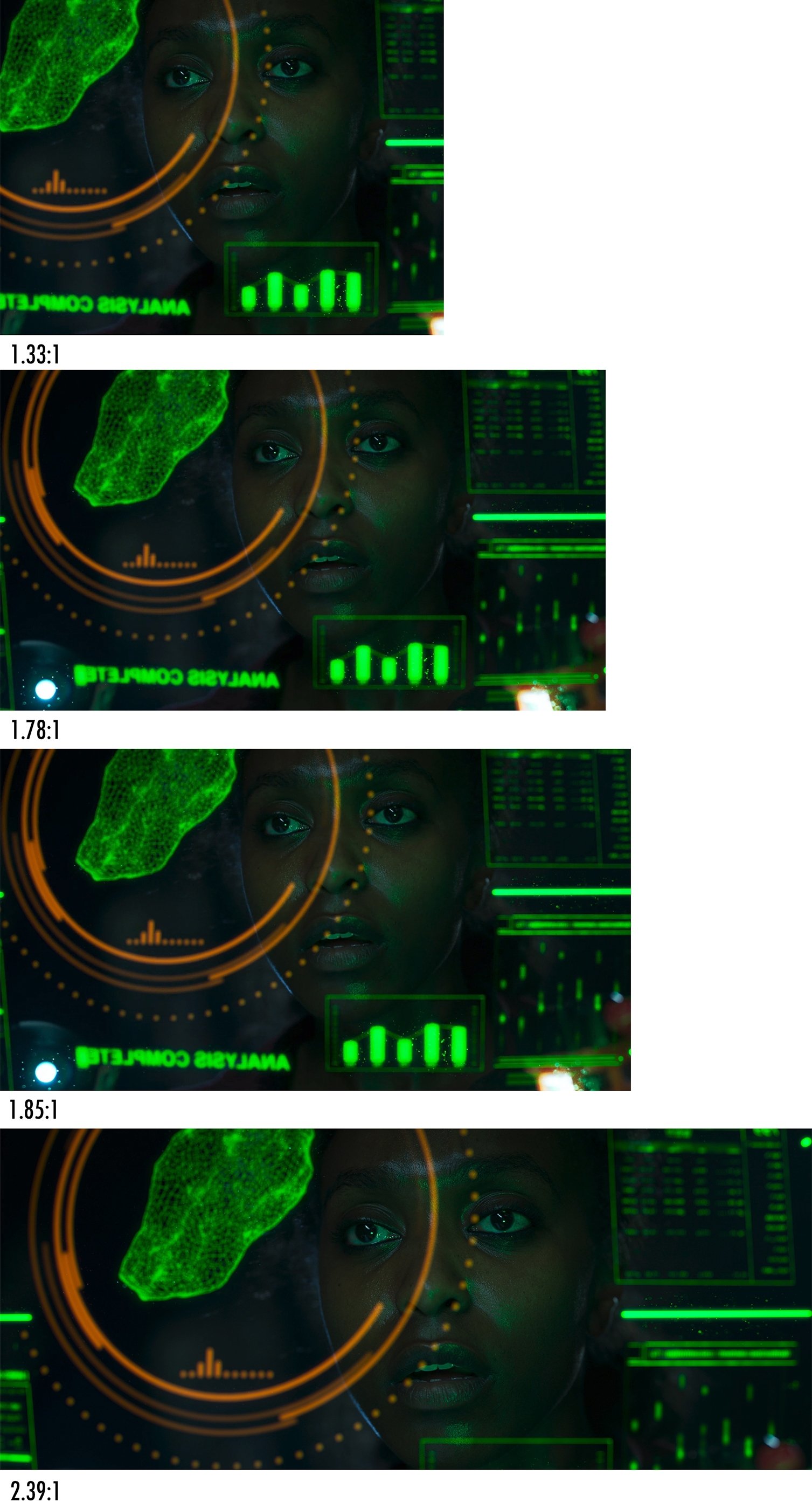

Aspect-ratio experiments have been conducted since the very birth of cinema — though starting in the late 1920s, with the advent of sound, there were many years of little to no experimentation, partly as the result of two world wars. Technology advanced fairly quickly after World War II, however, and when television became commonplace, the shape of its screen was based on the primary cinema standard of the time: 1.33:1, or 4:3.

Format Wars

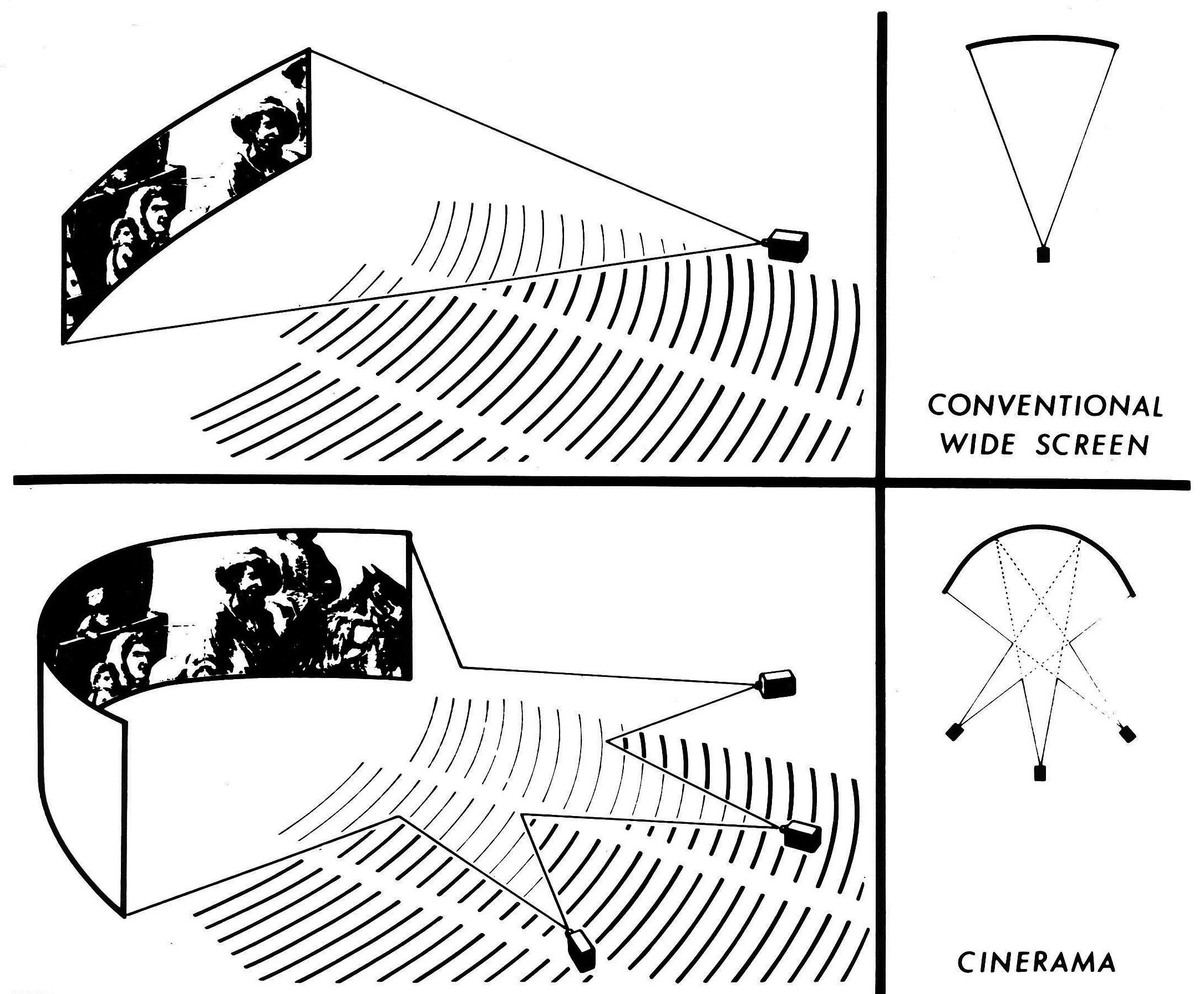

By 1952, the number of U.S. homes that had television sets was approaching 30,000,000 — and simultaneous to the rise of this new technology was the premiere of the documentary This Is Cinerama, which introduced a new kind of theatrical experience that featured specialized projection and super-widescreen presentation. This Is Cinerama and the handful of Cinerama-photographed films that followed were shot with a unique three-in-one camera system onto three individual strips of film. The respective reels were then projected from three projectors, and the slightly overlapping images created a single 2.59:1 image.

This Is Cinerama enjoyed phenomenal commercial success at a time when audiences weren’t going to the movies (more than 6,000 theaters closed in the U.S. in the early 1950s), but rather staying home and watching television. The combination of the decline of moviegoing and the success of Cinerama caused Hollywood studios to immediately put more widescreen movies into production to lure audiences back to theaters.

This sparked the infamous format wars of the 1950s, as dozens of different widescreen techniques were attempted.

Anamorphic, which originated as 20th Century Fox’s CinemaScope process, emerged as the most commonly used, offering an aspect ratio that settled into 2.35:1 (which became 2.39:1 in 1970). 1.85:1 was chosen as the standard for “flat” (non-anamorphic) spherical widescreen movies. These two formats became so commonplace in the United States that 1.33:1 practically died in cinemas. In Europe and other parts of the world, however, 1.66:1 became the dominant flat widescreen theatrical standard, along with 2.35/2.39.

Television, however, remained unchanged at 1.33:1 for nearly five decades.

Squeezing a Rectangle Into a Square

Theatrical releases were transferred to television at 1.33:1, significantly compromising many filmmakers’ framing and creative intent for images that originated in 1.66:1, 1.85:1 or 2.35/2.39:1.

2.39:1 films were transferred to television through a re-composition of the widescreen image, which was achieved either by adding edits that would cut from one side of the screen to the other to show pertinent information, or through a pan-and-scan process wherein the composition would dynamically “pan” across the frame during the shot, adding potentially awkward movement — and certainly movement the filmmakers did not intend.

In the current landscape, there’s no fixed standard for home exhibition.

Many 1.85:1 and 1.66:1 films — depending on how they were originated — were either vertically cropped (cutting off the sides of the im-age), or “opened” to show more image in the frame than was intended. (The latter method was employed for 1.85 and 1.66 films that were shot “full gate” — a common practice — which meant they were captured in 1.37:1 aspect ratio, the actual “Academy” format, for subsequent cropping to 1.66 or 1.85 for theatrical presentation.)

For more than 40 years, these destructive processes were the only methodologies available for transferring widescreen movies to tele-vision. Filmmakers and serious film aficionados cried out for another option.

Letterboxing

In 1984, RCA introduced letterboxing on its Capacitance Electronic Disc SelectaVision video-on-vinyl home-format release of Federico Fellini’s Amarcord. Letterboxing allowed a rectangular widescreen image to be presented in its full width on a square-ish television screen by reducing it in size and filling the empty space above and below the image with black bars. At about the same time, the Criterion Collection released, on LaserDisc, its first letterboxed title — Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

Steven Spielberg was a vocal critic of cropping and pan-and-scan techniques, and he convinced Warner Bros. to release The Color Purple on VHS in a letterboxed format. Explanatory text that preceded the 1985 film clarified the presence of the black bars as normal. When Spielberg’s drama Always was released on VHS a few years later, the same disclaimer was enhanced by a video message in which the filmmaker explained the reason for letterboxing.

One difficulty in presenting the proper aspect ratio when letterboxing for television was that with early video, picture resolution was lost. Since the VHS format had only 240 horizontal lines of resolution available, losing nearly 100 of them to black bars on a 2.35:1 aspect ratio made the image quality worse than many viewers would tolerate.

When cinéastes propelled the rise of LaserDiscs in the early 1990s, greater effort was made to preserve filmmakers’ creative intent, and letterboxing became more prevalent. An image that didn’t “fill” television screens was still unappealing to many consumers, however — so, in an effort to please everyone, studios released hundreds of theatrical titles on home video in two versions: one pan-and-scan and one letterboxed. That changed in 2003, when Blockbuster Video (which controlled the lion’s share of the home-video market) announced it would give preference to letterboxed DVDs in its rental business — which heralded a new era in which titles were only released in the wide format.

The benefit of letterboxing on DVDs was that the format evolved into a modified anamorphic image scheme, in which the widescreen picture was compressed in the full video resolution and then unsqueezed into the middle of the screen by the DVD player, which would then add the black bars at the top and bottom. This meant that the full video resolution was used on the actual picture area, and none of it was wasted in the bars — so a viewer’s experience of the image’s resolution was now limited only by the pixel count of the television moni-tor itself.

Even as letterboxing came to dominate the home-video market, broadcasters remained reluctant to present letterboxed images on air. Even premium cable channels refused. It was extremely rare to see a film in its proper aspect ratio on any broadcast, basic- or pay-cable channel.

HDTV

The introduction of high-definition television in the late 1990s also introduced a new aspect ratio: 16:9, or 1.78:1. The wider HDTV screen made it slightly easier for the masses to accept the black bars at the top and bottom of their screens. (Viewing options built into these new TVs also allowed the user who was opposed to letterboxing to expand the image by magnifying the picture to fill the height of the screen, thus cropping the sides and eliminating the bars.) Home-video releases in 1.66:1 and 1.85:1 just about died out.

In 2013, Netflix presented the series House of Cards, its first original production, in a native letterboxed format of 2.0:1, a compromise between 2.39:1 and full-screen 1.78:1. (This has since become a popular aspect ratio outside of the broadcast networks.)

Cable and Broadcast Catch Up

Eventually, letterboxing spread to cable television, appearing on such shows as FX’s Fargo (2.0:1 since Season 3), Showtime’s Escape at Dannemora (2.39:1), and USA Network’s Treadstone (1.95:1).

For decades, HBO maintained a “no black bars” policy — The Sopranos and Game of Thrones were 1.78:1 — but this legacy was broken in 2019 with their series Chernobyl (2.0:1) and Westworld (2.39:1 and 1.78:1). HBO has twice conducted studies of consumer response to letterboxing and determined that even today, it is neither widely understood nor appreciated by average TV viewers. According to HBO’s research, these viewers are distracted and confused by the black bars and still feel like they’re missing something.

Broadcast networks have been the slowest to change, but The CW aired its 2019 series Batwoman and Nancy Drew in 2.0:1, and Fox presented Prodigal Son in 2.0:1 that same year. Meanwhile, Netflix and Amazon have been leaving the decision entirely to the filmmakers — offering a variety of choices that include 1.33, 1.66, 1.78, 1.85, 1.89, 2.0, 2.1, 2.2, 2.35, 2.39 and 2.40:1.

So, while movie theater projection standards are mostly fixed at 1.33, 1.43 (Imax), 1.66, 1.85, 1.89 (Digital Imax) and 2.39 — with a rare outlier like Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight in Ultra Panavision 70 2.76:1 (70mm theatrical) — in the current landscape, there’s no fixed standard for home exhibition.