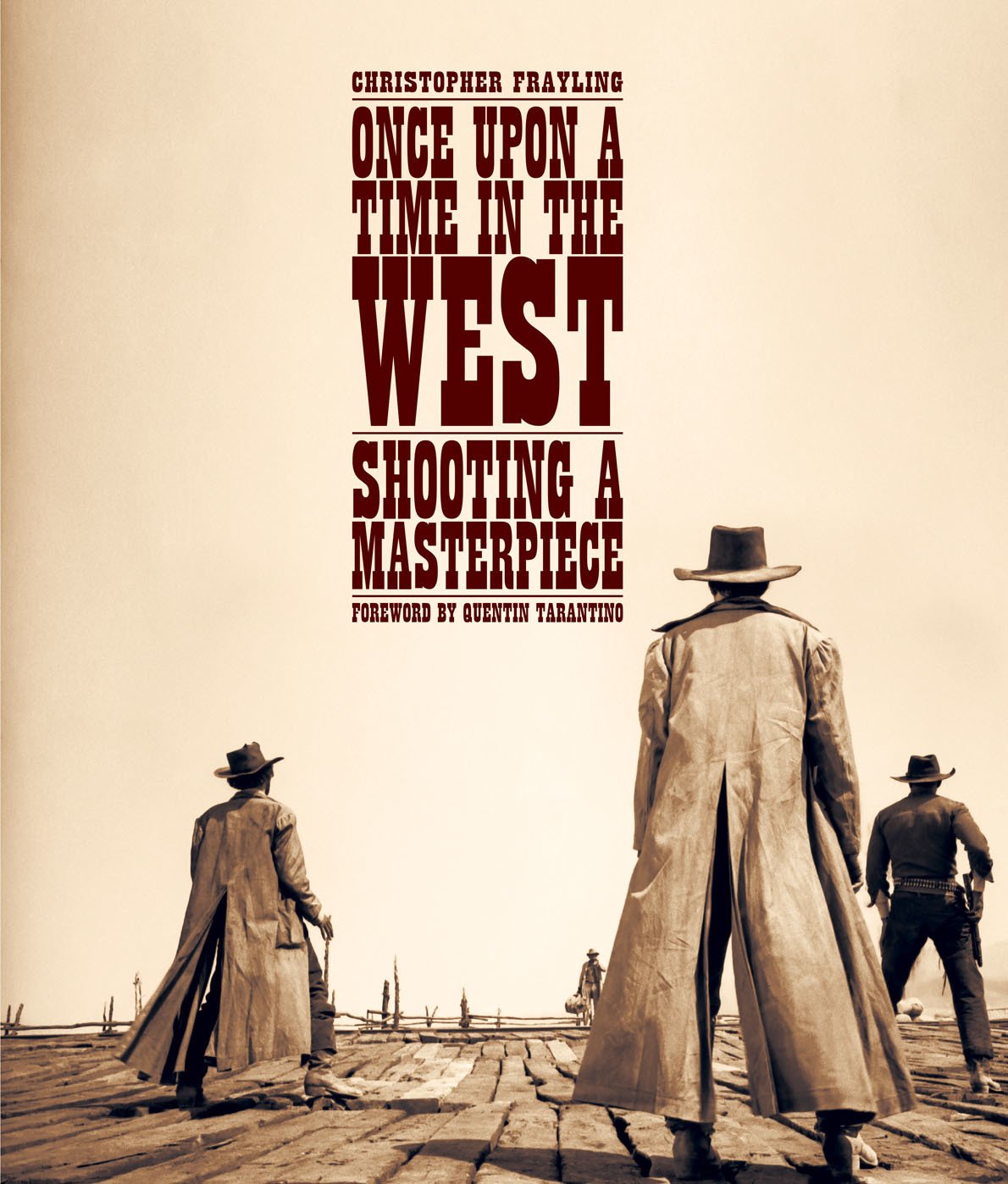

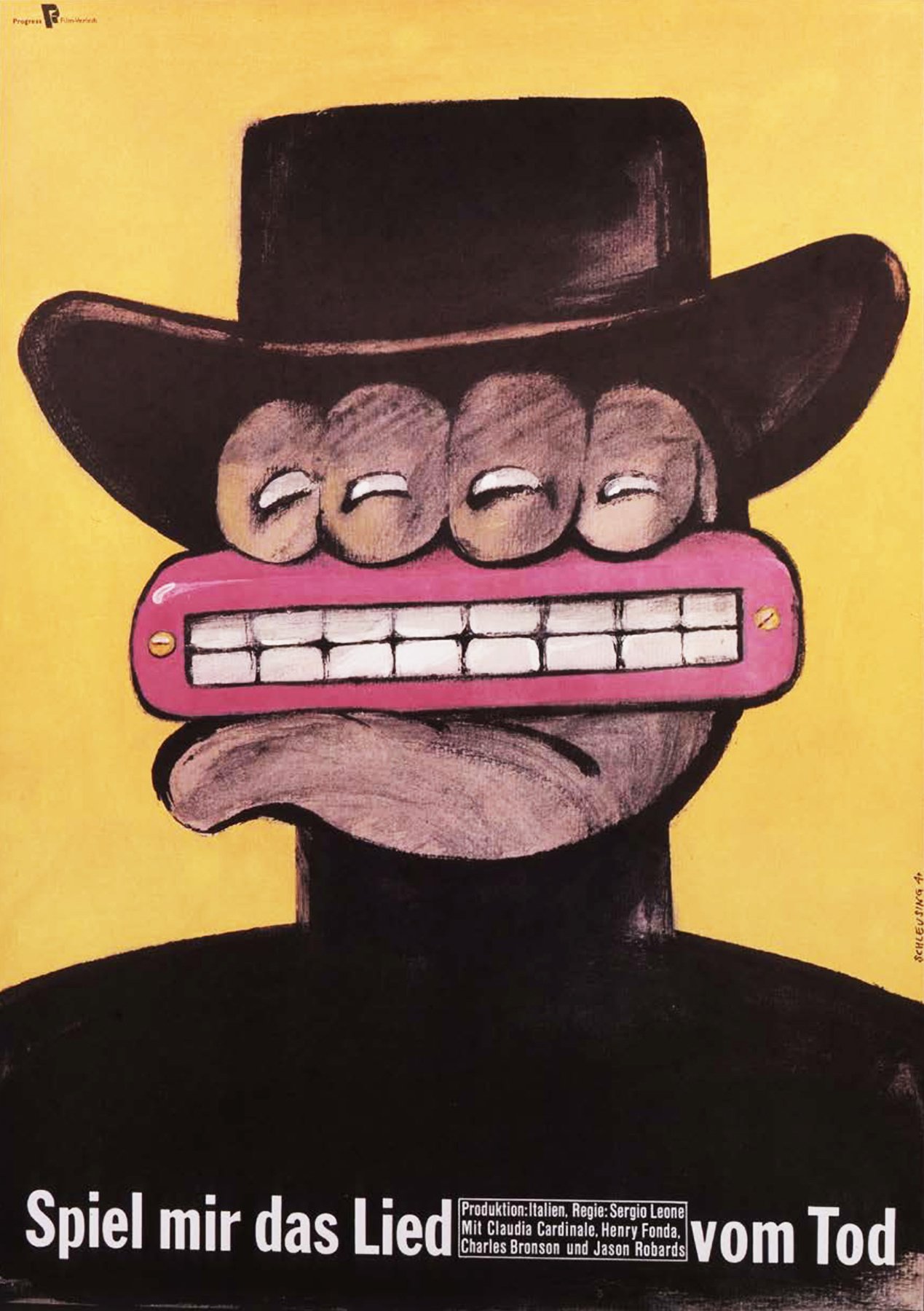

Once Upon a Time in the West: Shooting A Masterpiece

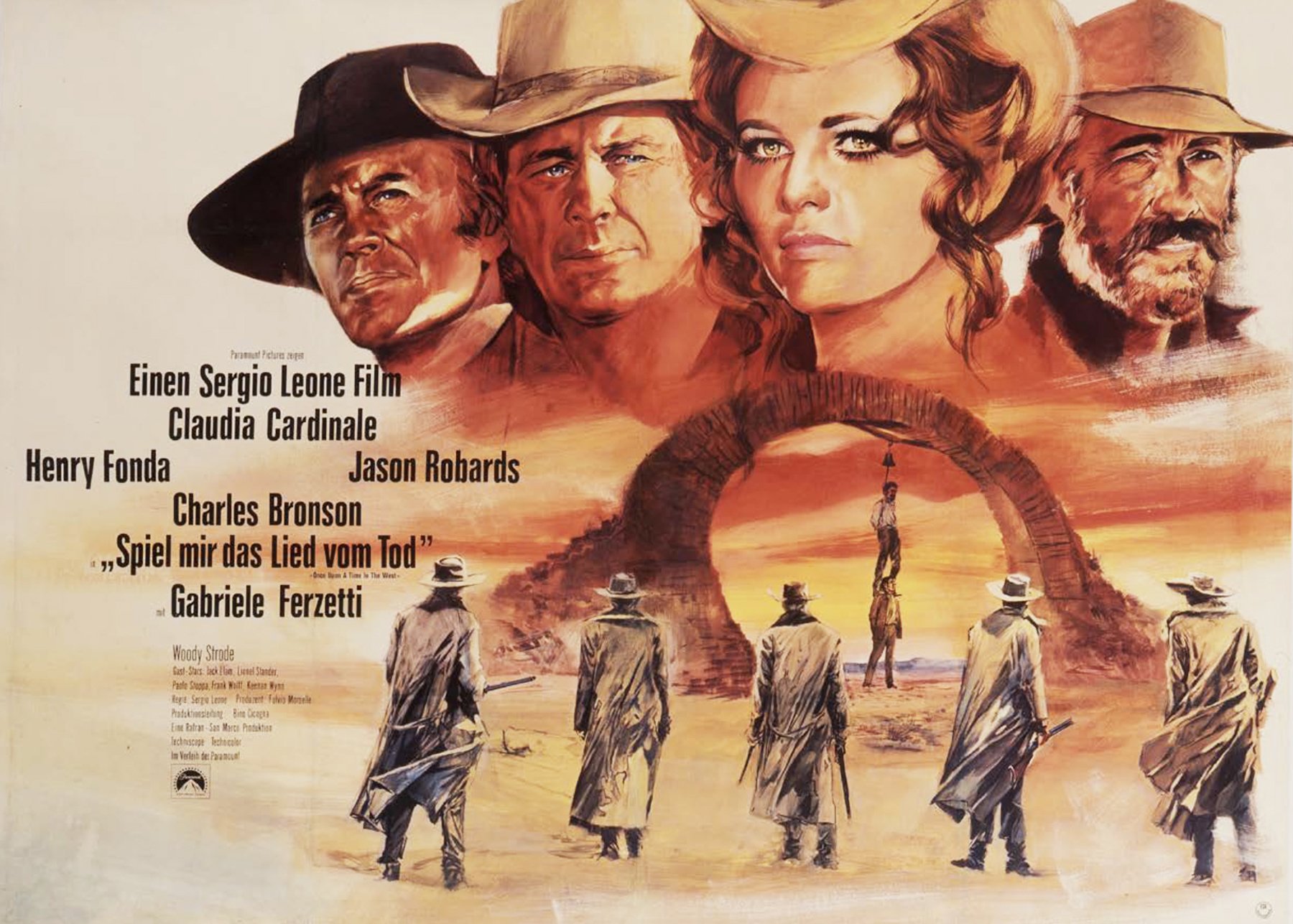

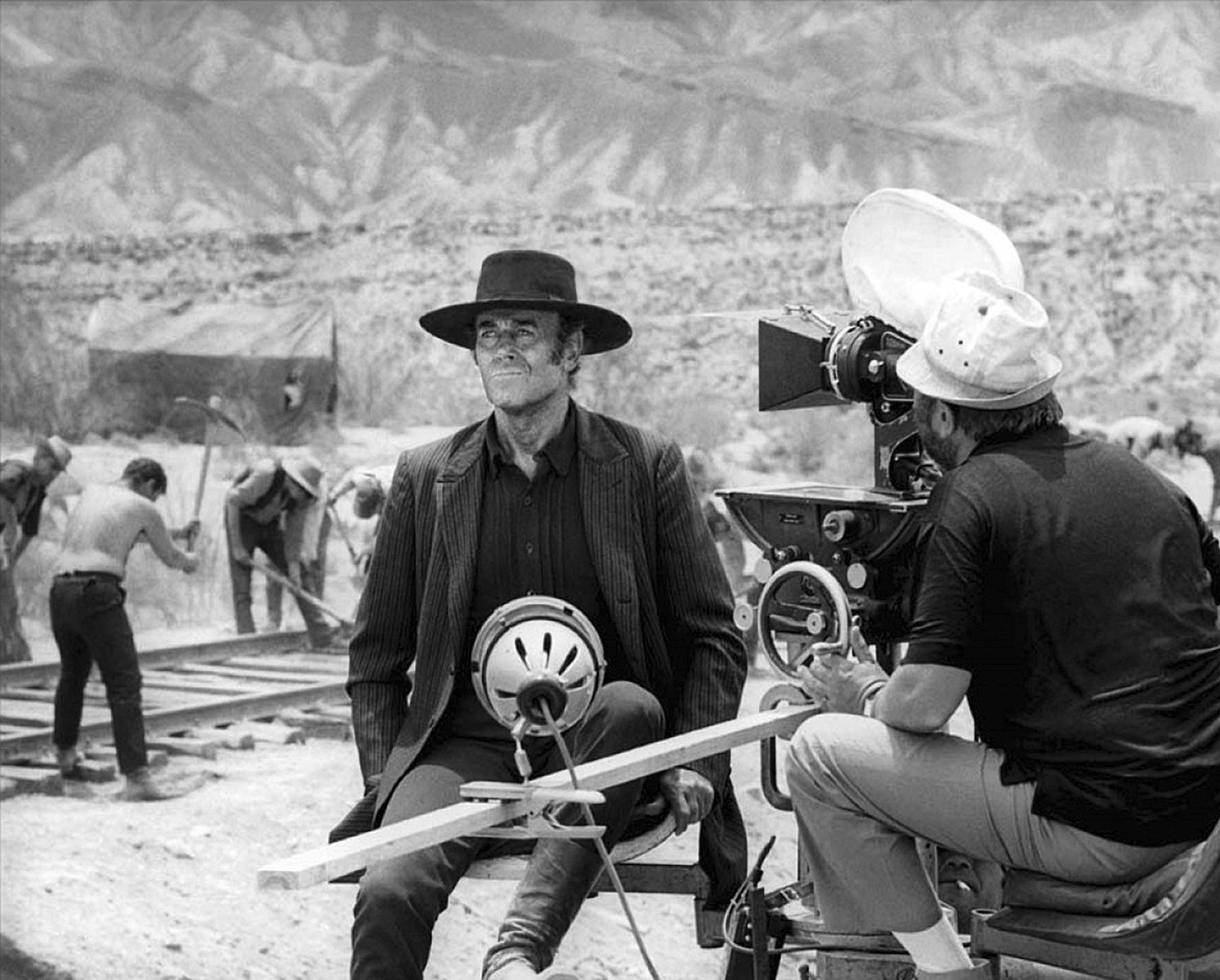

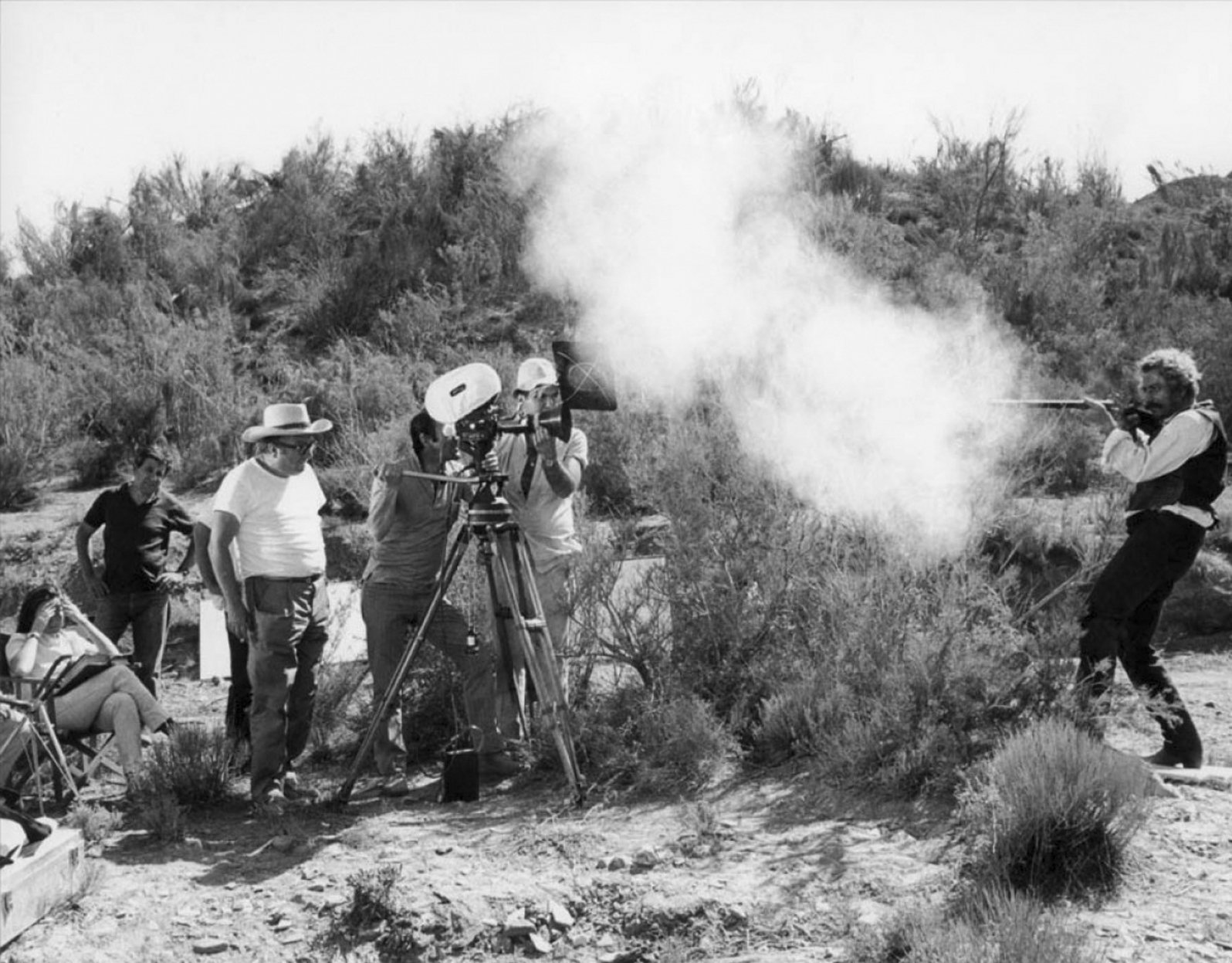

Esteemed Italian cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, AIC recalls working with director Sergio Leone on this memorable 1968 Western.

Esteemed Italian cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, AIC recalls working with director Sergio Leone on this memorable 1968 western.

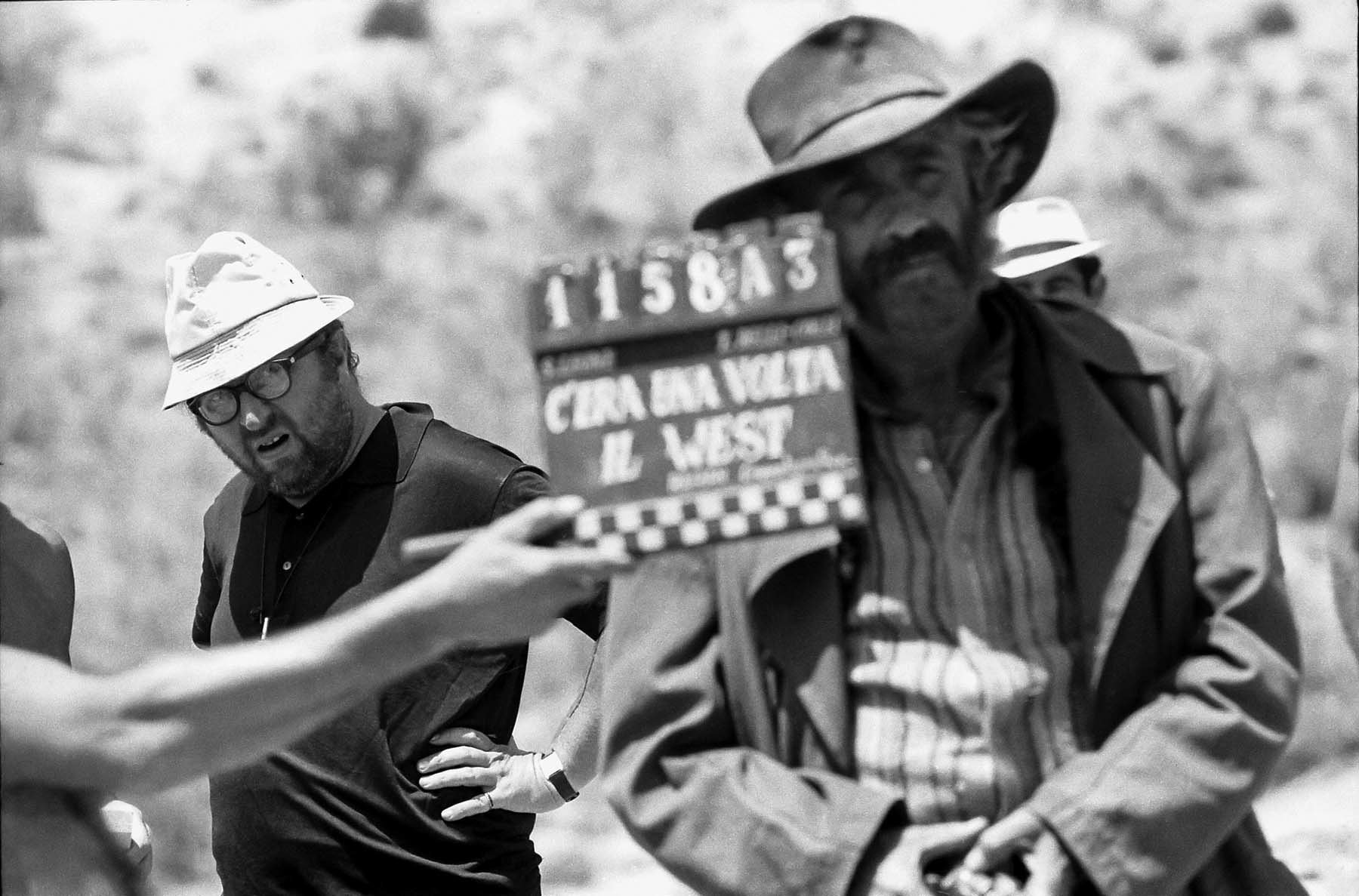

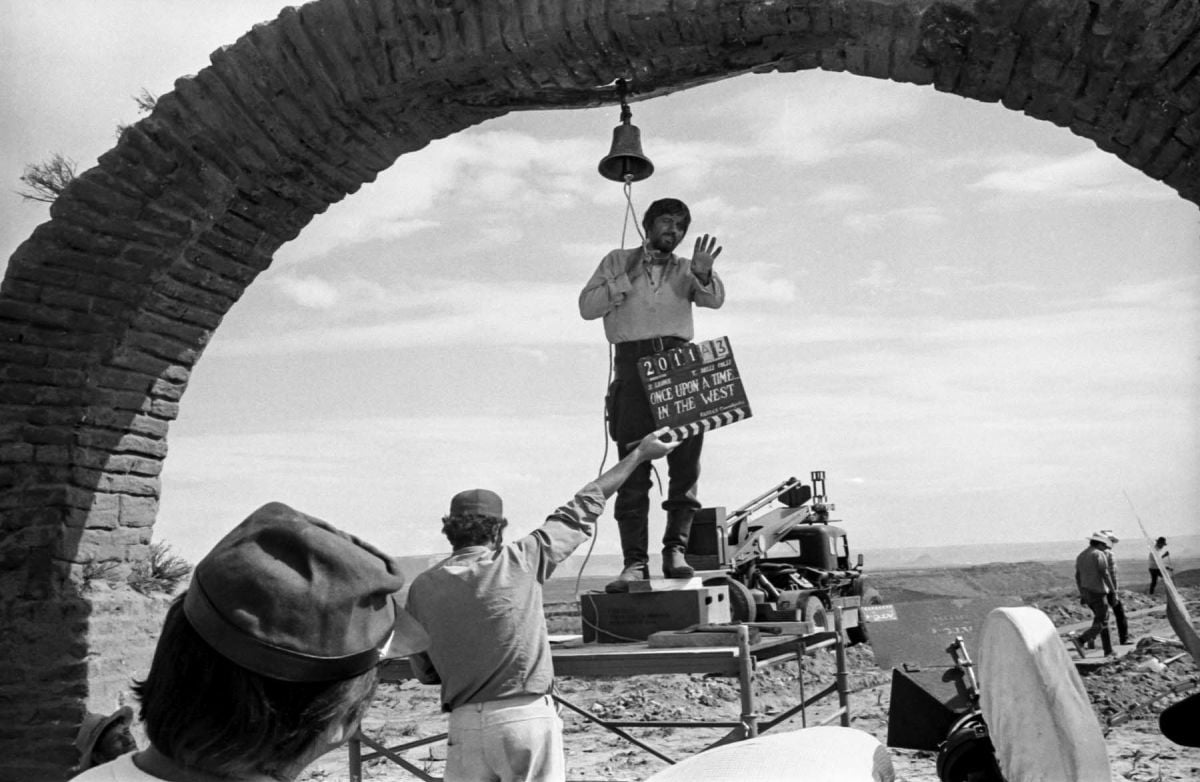

The following interview is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Once Upon a Time in the West: Shooting a Masterpiece, written by Sir Christopher Frayling and published by Reel Art Press. To be released on April 23, the in-depth, 336-page tome details the entire production, from script to screen — celebrating the 50th anniversary of the film’s release.

With a forward by Quentin Tarantino, the book also features tribute essays by John Carpenter, John Milius, Joe Dante and Martin Scorsese.

In the chapter below, Delli Colli discusses his work on this epic “Spaghetti Western,” his long collaboration with Leone — including The Good, The Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon A Time in America (1984) — and memories of often shooting many, many takes to achieve the visual perfection Leone sought.

This conversation occurred in two places — in France at the Montpellier Festival of Mediterranean Cinema, October 1998, during a symposium and exhibition devoted to Sergio Leone and Carlo Simi; and at the Taormina Film Festival in Sicily, July 2002. Tonino had a notably down-to-earth sense of humour — and was well-known to be touchy about critics and academics. He kept calling me “the Professore”...

Q: When you worked together on The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, were there a lot of discussions with Sergio about the visual aspects of the project?

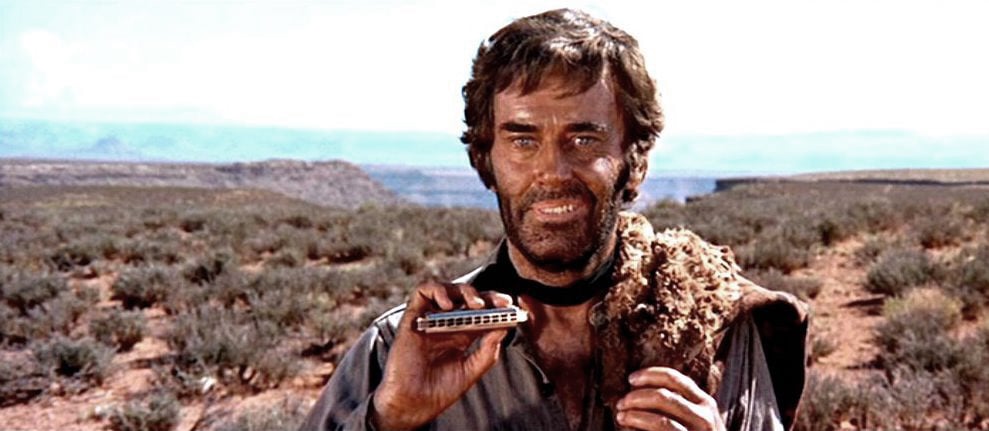

TONINO DELLI COLLI: You know, a critic once asked me about the sequence at the Indian cliffside village in Once Upon a Time in the West and the sunset lighting. He asked if I got inspiration from a painter for this. ‘What, the sunset?’ I’m afraid my answer was short and mean, and he never spoke to me again! The thing was, with The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, that you can’t have too many colours in a Western: red, brown, beige, earthy, off-white. A lot of dust, constructions made of wood, sand-coloured tones. There wasn’t really much to talk about. We shared the same point of departure: not too many colours. [Costume designer] Carlo Simi was a fantastic colleague, a great help. Together with Sergio, they had studied a lot of books on the American West, and in the Almería scenes of For a Few Dollars More they had created a setting, for the first time, exactly the way Sergio wanted it. Sergio and I understood each other very well indeed. There was never any need for much discussion.

Q: But didn’t Sergio Leone use paintings as reference points for the visuals? Giorgio De Chirico, for example?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: While we were actually working, we didn’t refer to paintings. Sometimes we referred to them during the preparation stage as a kind of shorthand for costumes and sets, but that’s about it. For documentation rather than composition. Maybe for lighting, sometimes. We certainly looked at photographs of the period — that library of American books collected by Sergio and Carlo Simi. But, look, whatever Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC; another great Italian cinematographer] says, we are not making poetry. We turn the lights on, and we switch them off. That’s what we do. I don’t remember De Chirico. The resemblance could be by accident.

Q: Sergio was famously meticulous about his work, a real perfectionist. Did this create difficulties?

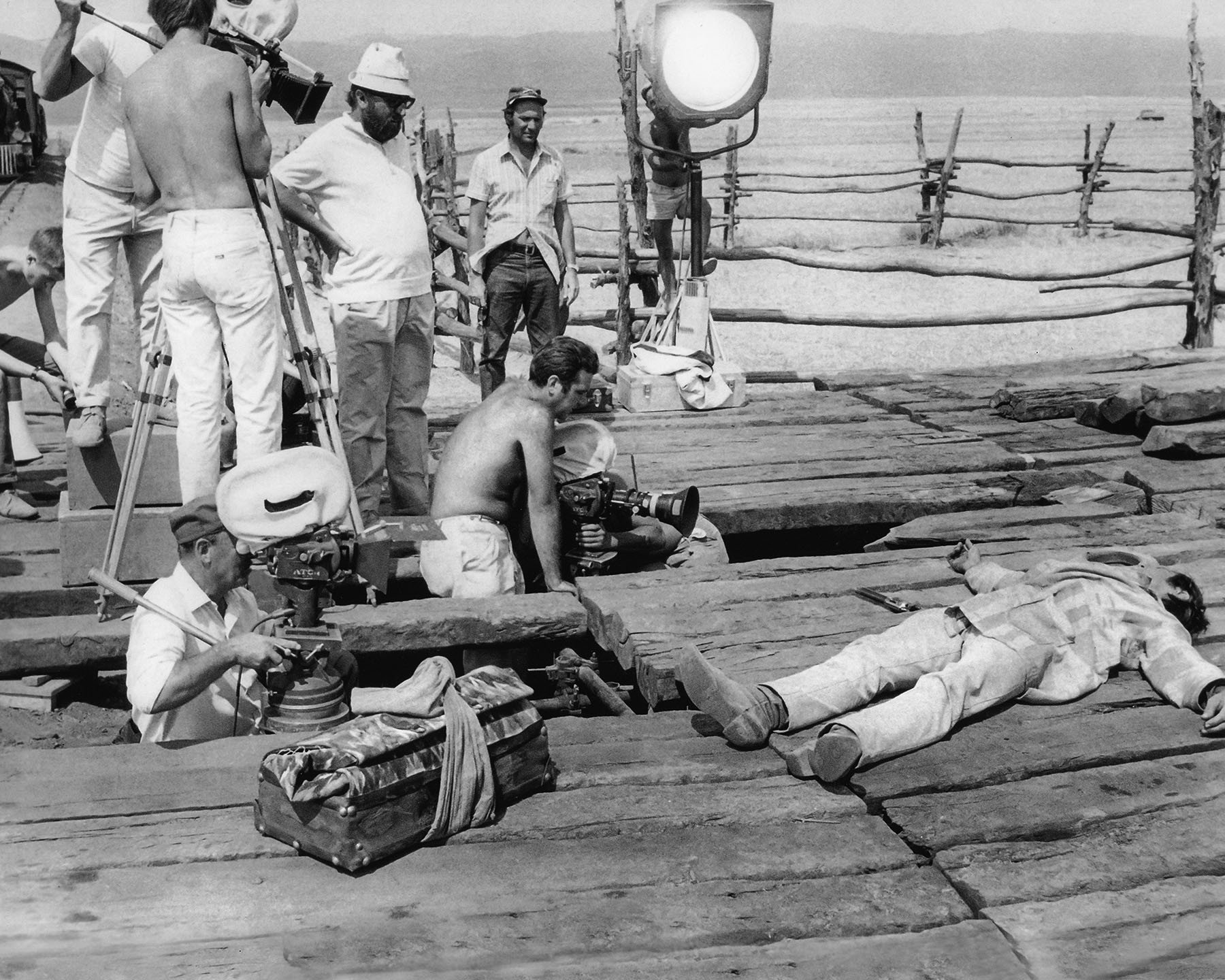

TONINO DELLI COLLI: The one problem about working with him was that he would never leave the set until he had completely finished what he was doing. We worked sometimes for 14 to 15 hours a day. Each day was filled to the brim! In America, those extra hours would have been well paid, but not with us. There were sometimes discussions about the long working hours. They consisted of Sergio saying,‘ Bugger off — we’ll continue till I am ready.’ He would start the day with a wide lens and finish with a big close-up; the close-ups were usually in the evening. In Spain there was daylight till 9:30, so we worked from first thing in the morning till late. I would try and pack away the camera, shut it away at the end of the day, and he would remember that there was just one more close-up to do. I would tell him, ‘We can shoot it tomorrow,’ because it could be done at any moment since you couldn’t see anything else in the shot apart from the extreme close-up.

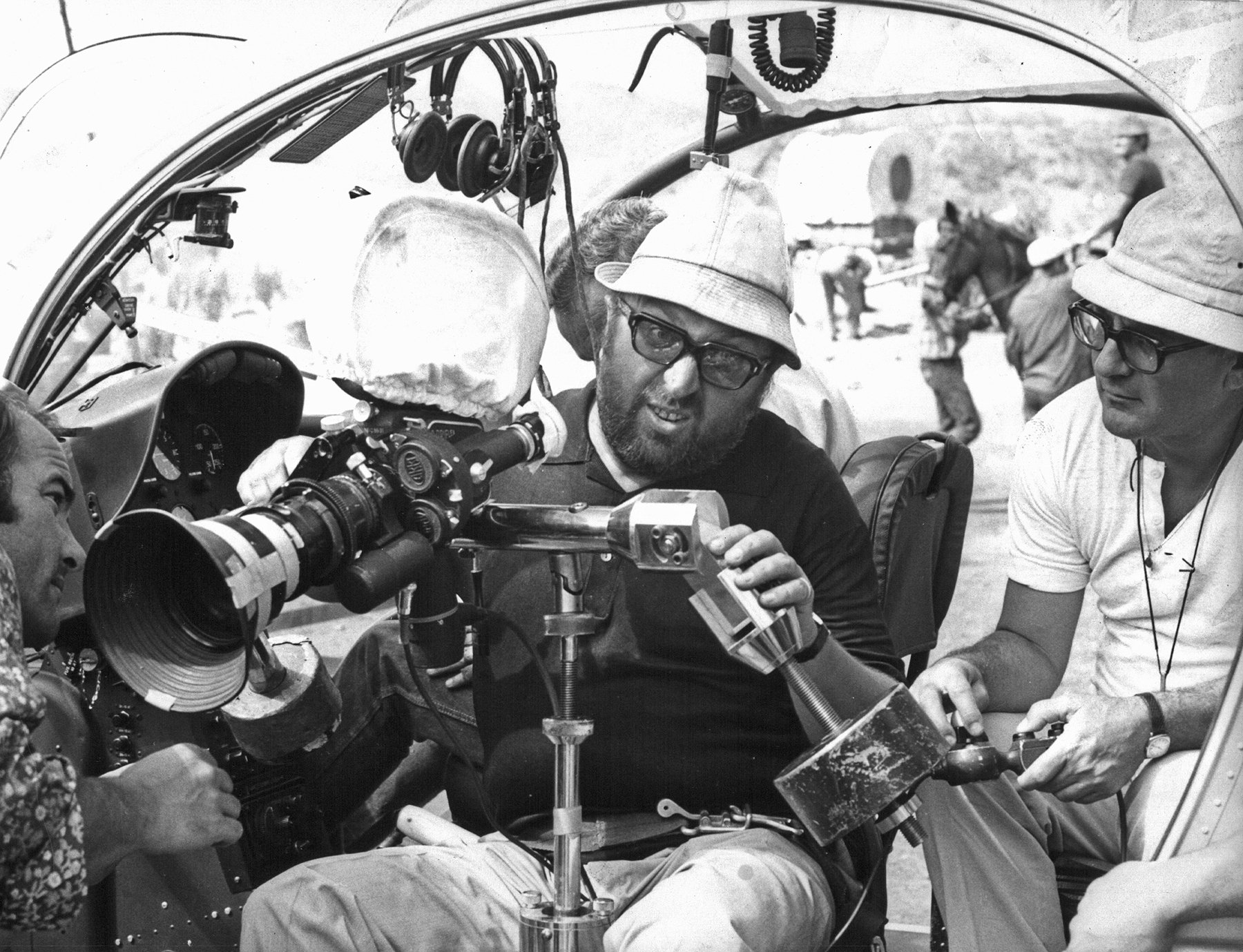

Q: He seems to have known a lot about the technology of filmmaking and enjoyed it too.

TONINO DELLI COLLI: He put a lot of work into the script — a lot of people would work on it; he contributed but there were also screenwriters. Because he was never happy and made a lot of changes... then he would closely follow this detailed script. Technically, he was perfect; technically, he was a great director. Sometimes he would ask for a small dolly of 20 centimetres, and I would say, ‘Why a dolly?’ but when it was edited, you could notice those 20 centimetres. The public didn’t realise about things like this at a technical level, but felt them psychologically. His films were very carefully shot, and it paid off with audiences. He was very precise. He would rarely improvise, because he had it all in his head. He knew in advance what each set-up would be like, and he knew how each set-up would be composed. He’d never just show up in the morning and then decide...

Q: Were the scenes at the cemetery — the end of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — a particular challenge?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: When we filmed Eli Wallach running around the cemetery, I had the idea that in order to cut the close-up and the long-shot together, I’d put a pole on the tripod and put a camera at each end of it — at one end a camera with a 25mm lens and at the other a camera with a 75mm lens. The cameras turned together, so if the actor was framed with the 75mm lens, the 25mm would automatically be okay as well. It took half the time to shoot it, and it was better for the editing as well. In this way, we made a lot of circles all at the same time, while Eli Wallach did a lot of running. That’s how that was done.

Q: Sergio liked to use music on the set, didn’t he?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Morricone had a starting version of the music, ready and recorded, which would be elaborated on and improved later. Sergio wanted music from the beginning of the project, before starting to shoot. He usually had it playing in the studio for the interiors, which used to irritate me because I couldn’t talk to the electricians. He liked to work with a musical track, to create atmospheres. But when we actually went for a take, he cut the music so we’d have good production sound.

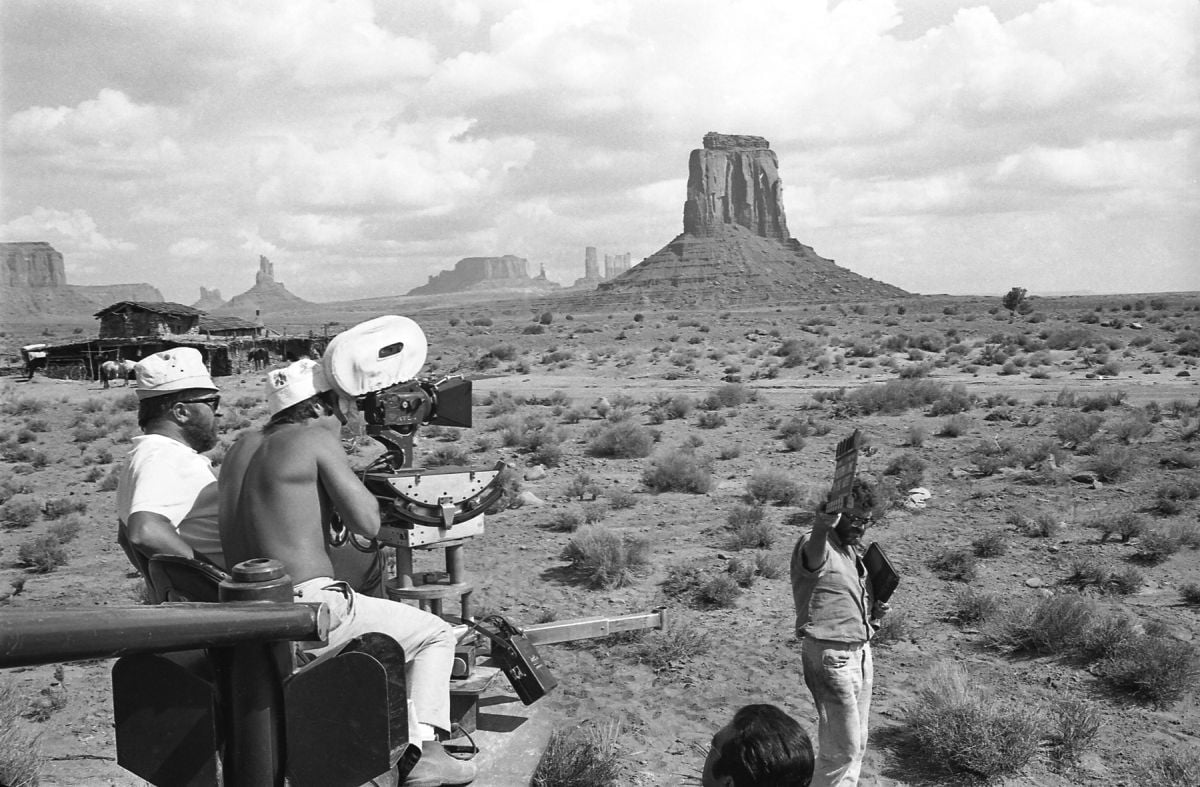

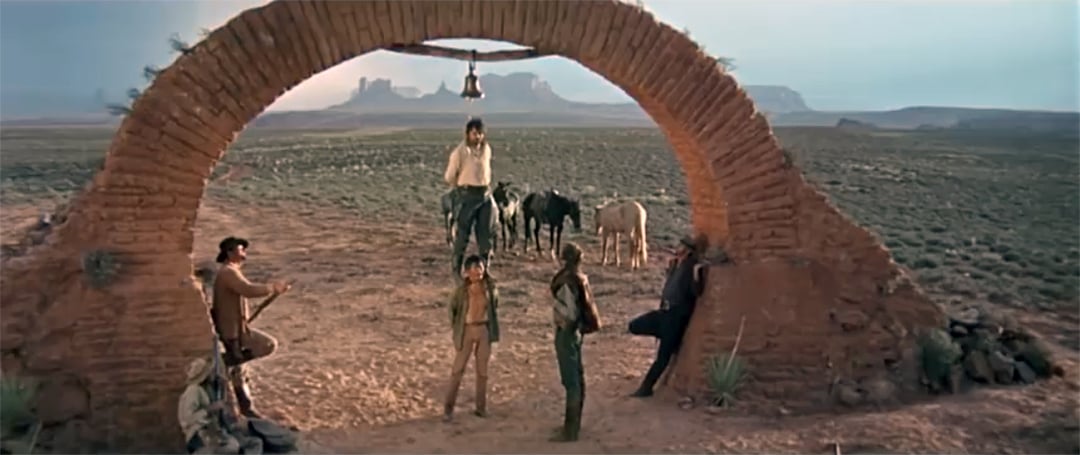

Q: You’ve mentioned the recce to Monument Valley for Once Upon a Time in the West...

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Yes, we were in Arizona, looking for a place to build the exterior of the posada, the place in the desert where Claudia Cardinale and Paolo Stoppa arrive. In the end, we found a good place with a small building, a hut, on it. We called to see whether anyone was at home, and we met the owner. You won’t believe this, but when we arrived he was making pasta — and doing it by the book. ‘First I have to finish this, and then we can talk.’ He was measuring fettucine with a ruler! Anyway, Sergio said to him, ‘You don’t do it like that, you do it like this’ — and Sergio taught this man how to make Italian pasta! The man simply couldn’t believe it... a pasta lesson in the Arizona desert!

Q: And after the recce — filming in Almería, trying to make it match the Arizona desert...

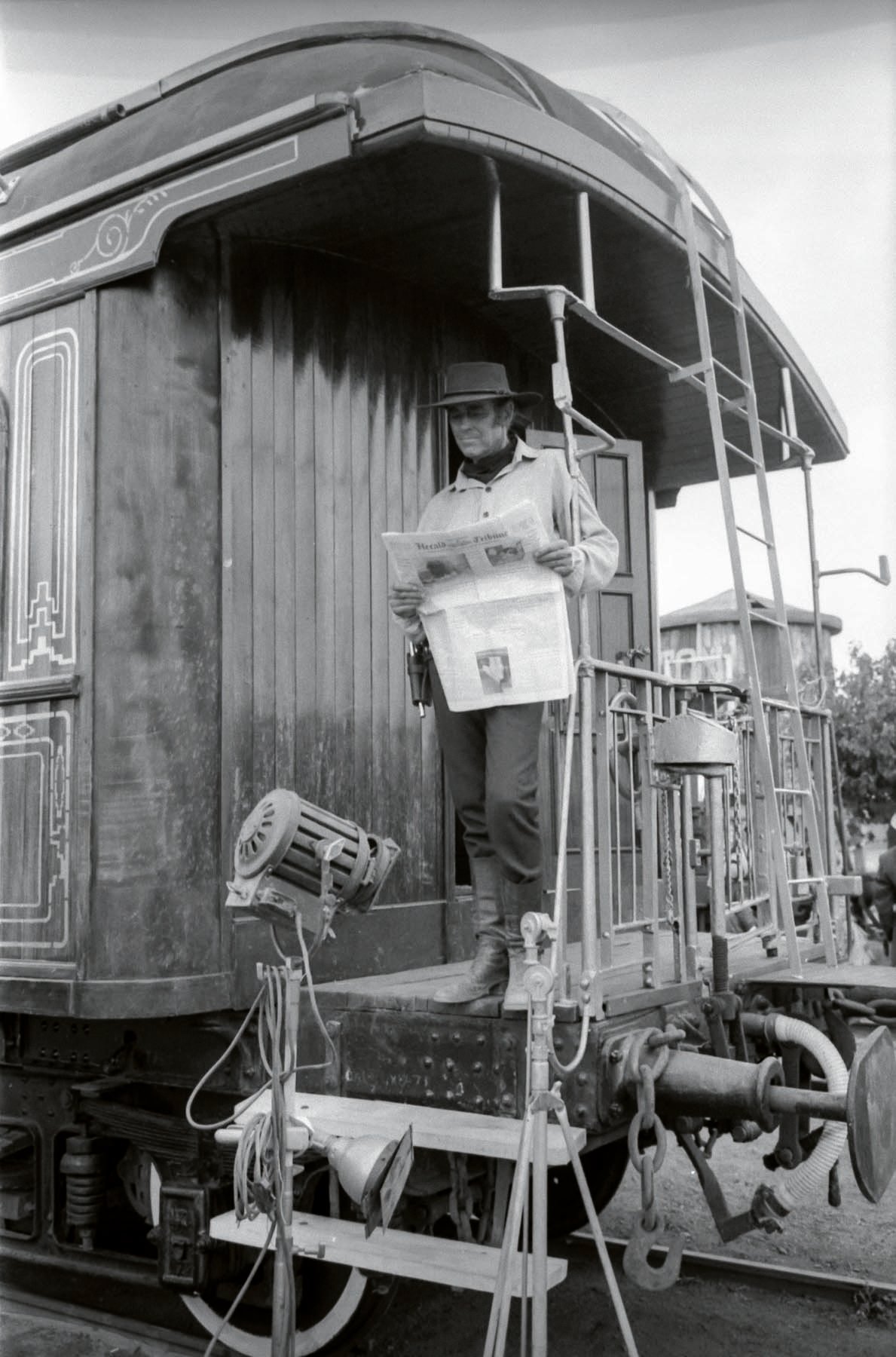

TONINO DELLI COLLI: In Almería, Sergio even had two kilometres of railway built and arranged for the locomotive and wagons to be transported to the canyon on the location. When he had made up his mind about something like that, it was impossible to change it. We argued a lot about things over the years, but he was, above all, a good friend.

Q: I get the feeling that you are not too comfortable talking about some of these things — that you share the philosophy of Tuco in the bathtub in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: ‘If you’re going to shoot, shoot; don’t talk!’

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Well, I do get a bit cross with some of the critics and the questions they ask. At the time, Sergio’s films did not interest the critics, though the films were huge commercial successes. Now, after the fact, things are being put right. Critics in general I don’t have much time for. They confuse films with Picasso paintings.

Q: How did working with Sergio Leone differ from other important directors?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Sergio made his own kind of film very well. Their slow pace... The films would last three, three and a half hours and you wouldn’t notice it.The audience in the cinema are proof of this, because Sergio Leone’s films made a lot of money. Someone made the calculation that in order to make that much money, most people must have gone twice to see the films, some even three times. Because they couldn’t have made that much money if people only went once. So his slowness certainly didn’t put people off.

Q: What sort of system did you use? Can you remember?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West we shot in Techniscope, which was a system developed by Technicolor printed on two frames of negative, anamorphic. That is, the frame was halved — so we saved a lot of raw film. And since it was the Technicolor trepellicole [three-strip] system, the old Technicolor system, the sharpness of the image was fantastic. Even now, when they have been reformatted for television, they have a sharpness about them... The old American films shot in Technicolor, too, have a depth of field... then they changed system, the old Technicolor system was over, and we now have the monopak, which has problems precisely with this sharpness.

Q: How did he manage with the English language?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Sergio didn’t speak much English, just like me, but he understood a little and he would cheat... He managed to get by in English because he was smart. And film is an international language, some things are all the same. And so when he spoke with someone in English,if the other guy smiled, he would smile; if the other guy looked sad, he would look sad, to make the other guy think that he understood. But he understood nothing. I would ask him, ‘Sergio — how much of that did you understand?’ And he would send me to hell. He’d say,‘Mind your own business.’ It was the same with Henry Fonda or Charles Bronson — but they all wanted to work with him, even the ones with big names, even though he would do 30 takes of a scene. Honestly, I remember the ultimate of this, on Once Upon a Time in America. Leone would do 25 to 30 takes until he was happy. When he said,‘Stop! Va bene,’ I would be changing camera position and then he’d say,‘I’ve been talking with De Niro, and he says he’d like to do one more.’ Then we’d do another 10. But they all wanted to work with him.Those close-ups!

Q: The same with the Westerns?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: During the Westerns, yes, he would do many takes. He wasn’t the sort of director to do just two takes, because he would perfect a take while he was shooting. He shot a lot of film.

Q: Did he have people he collaborated with regularly?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: More or less. Simi was his set designer. I did three films. Baragli was his editor, Morricone for the music. Morricone practically got his start with him.

Q: Did it take a long time to shoot his films?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Sergio’s films took 13, 14 weeks—but they were really ‘double films’ because they were three to three and a half hours long, then he would cut a little...! For instance, America was ruined by the Americans. In Europe, everyone saw the real film. In America, they ruined it, cut all the flashbacks and turned it into a ‘filmetto’... The Americans certainly didn’t help Sergio — like they don’t help European cinema. Same with Once Upon a Time in the West. You had to see the real film in Italy or France.

Q: Did Sergio invent special ways of shooting?

TONINO DELLI COLLI: He loved the Chapman crane. When he saw one, it made him happy and he would get up on the Chapman and never come down!

Q: Have you been back to Almería, since West? Some of the sets are still standing.

TONINO DELLI COLLI: Yes. I went back to Almería after they’d finished with the Western films. Almería had 10,000 inhabitants in the old days — now it has 60,000. Almería was built up with money from the movies. They started constructing residences, hotels, then restaurants. There were 10,000 — now 60,000. I went back a few years ago, and didn’t recognise it any more.

In February of 2005, the cinematographer was honored by the ASC with its International Award for his exemplary body of work. You can read our entire tribute piece here. He would die just months later in Rome at the age of 81 on August 16.

In 2019, the film was included in the ASC’s roster of 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century. Learn more about this list here.