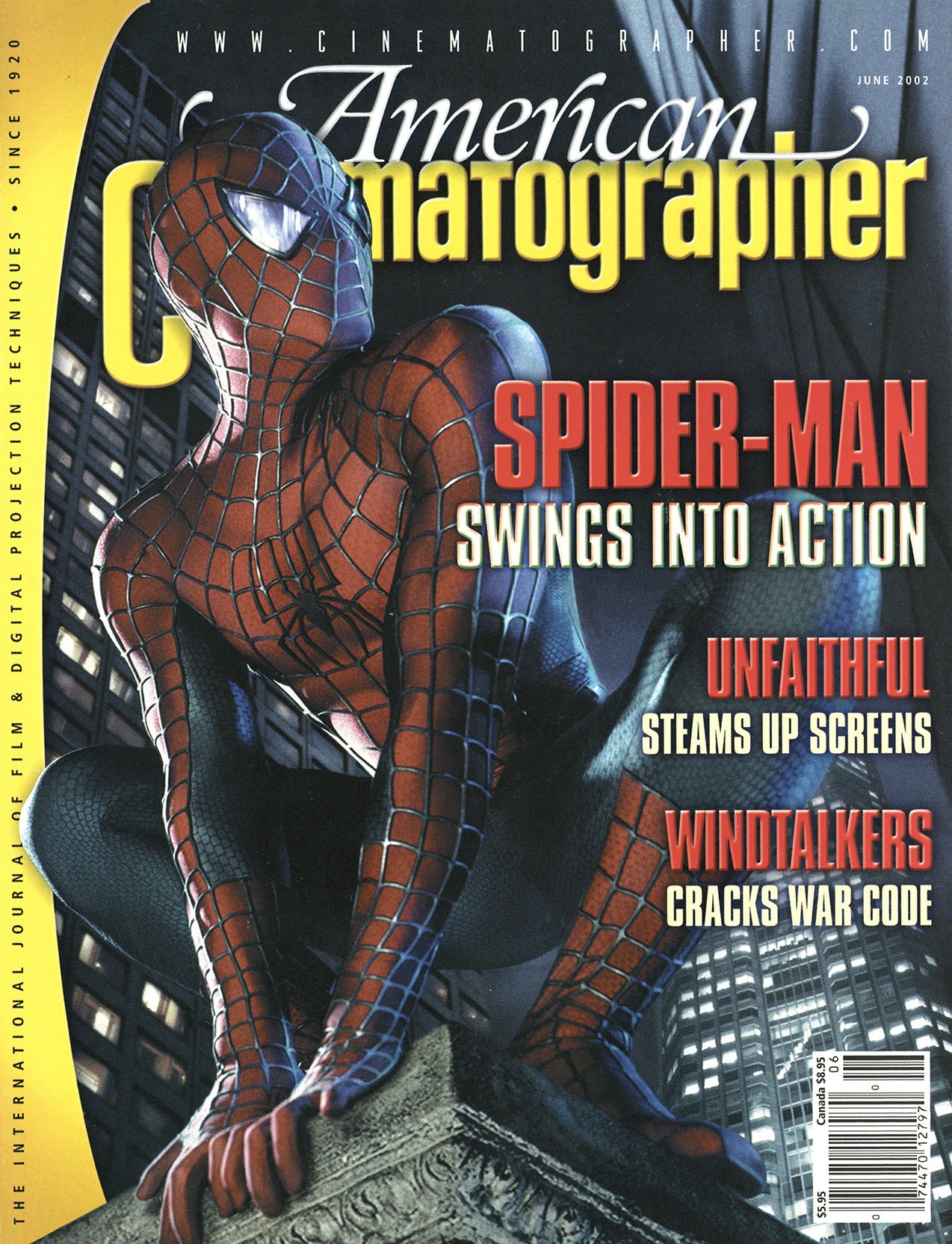

Spider’s Stratagem: Spider-Man

Don Burgess, ASC teams up with director Sam Raimi to bring a Marvel Comics icon to life onscreen.

Unit photography by Zade Rosenthal and Peter Iovino

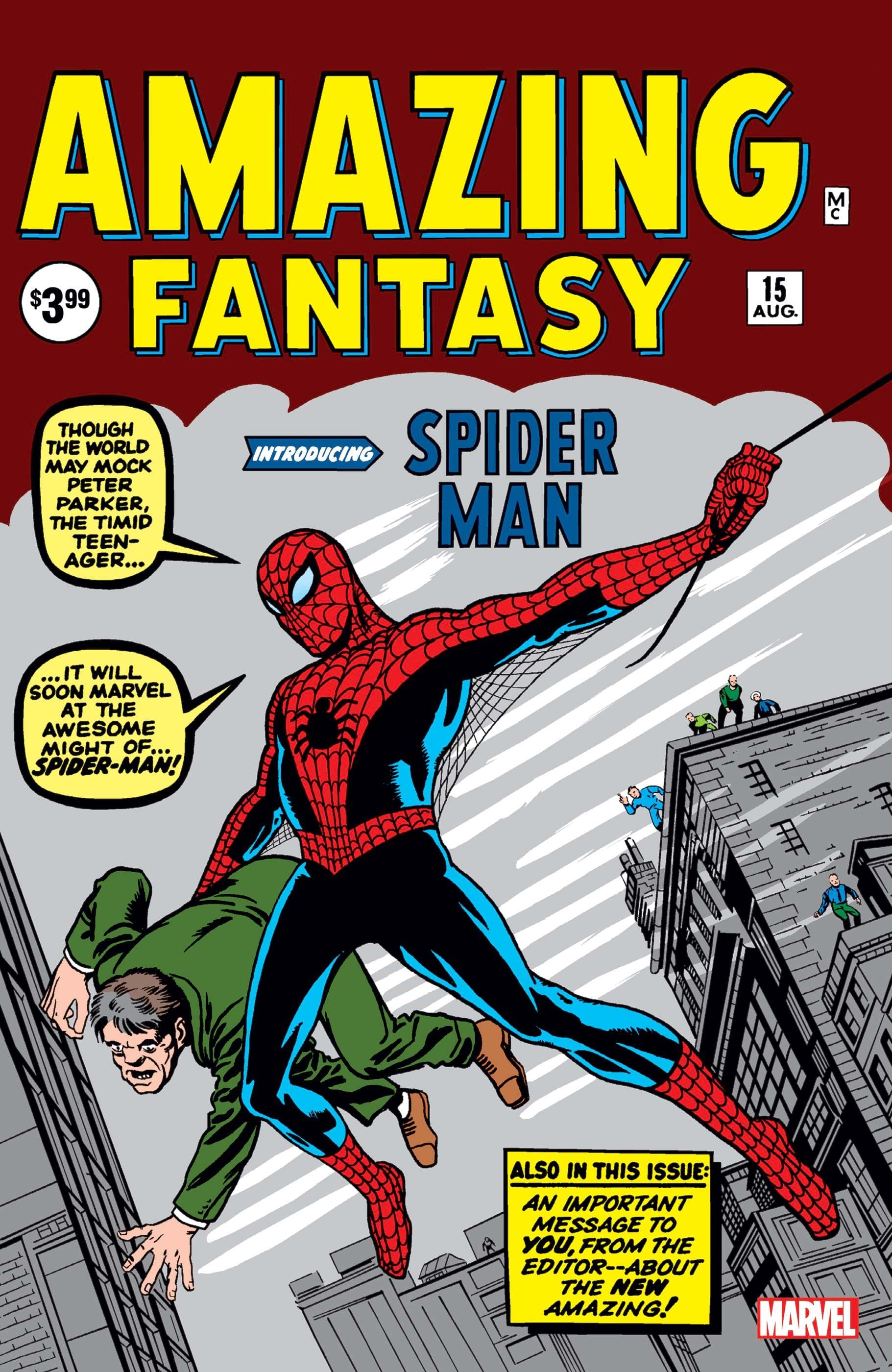

The brainchild of writer Stan Lee and illustrator Steve Ditko, Spider-Man (a.k.a. Peter Parker) swung out of the pages of an Amazing Fantasy comic book in 1962. He was a new kind of superhero, a teenager who struggled with the responsibility of his newfound powers but didn’t bother to hide from the limelight. Lee’s publisher had actually rejected the idea of Spider-Man as being too dark and scary for kids, so Lee slipped the web-slinging, wisecracking wonder into the last issue of Amazing Fantasy. Comic fans clamored for more, and a cultural icon was born.

After years of entanglement in a different kind of web — the Hollywood labyrinth of development and rights negotiations — Parker and his alter ego have finally come to the silver screen. Spider-Man marks director Sam Raimi’s first collaboration with cinematographer Don Burgess, ASC, whose resume includes an Academy Award nomination for his work on Forrest Gump (AC, Oct. 1994). “I was a bit hesitant when I first heard that Sam was interested in meeting me about Spider-Man,” confesses Burgess. “I hadn’t read a single Spider-Man comic, and I didn’t really have a lot of interest or excitement about doing a comic-book movie. But I’d heard a lot of good things about Sam and wanted to meet him, and once we sat down and had a conversation, he really got me excited about his take on the project.

"Spider-Man isn’t a stylized, Tim Burton kind of movie,” he continues. “Our approach is much more reality-based, a kind of heightened reality. The settings are New Jersey and New York City, but we searched for the unique qualities of those locations and heightened them. We found architecture and colors in New York that looked like they could be in a comic-book world, and our general approach was to take those elements and design the movie around them.”

Spider-Man’s origins are traced to a high-school field trip that takes Parker (played by Tobey Maguire) to a museum that’s exhibiting genetically altered spiders. After Parker is bitten by one of the creatures, he inherits its strength and agility along with a keen, ESP-like “spider sense.” As any red-blooded American teen might do, Parker first uses his new talents for profit, but after a tragedy hits close to home, he vows to dedicate his life to fighting crime. “The premise of the whole story is that with great power comes great responsibility,” Burgess observes. “That’s the lesson Peter has to learn along the way.”

Bringing the web-slinger to life in a live-action feature was no small feat. Spider-Man spends most of his time amid the rooftops of New York, swinging from one building to another on the steel-like strength of his webs. During preproduction, the filmmakers spent a great deal of time analyzing the New York skyline to see how feasible shooting on location would be. In the end, they opted for the greater control afforded by shooting on soundstages.

“For pretty much every sequence, we’d start with the storyboards and literally go through every frame and discuss how to break down the elements,” Burgess recalls. “What’s the foreground? What’s the middle ground? What’s the background? Are these real actors, stunt doubles or CG characters? Is it a background plate, a Translate or a painted backing? Is the foreground a set piece or a CG element? All of the departments sat down and hashed it out. That kind of work takes hours and hours, and it’s very tedious. It was also difficult to imagine the sheer number of shots we were talking about and how it would all work. Sam ended up incorporating a computer program that allowed the storyboard artists to not only draw the boards, but also create an animatic version of the sequence. That helped everybody understand what the shots were about and how each shot would tie into the next — it gave everyone a much better idea of what we were up against.

“Filmmaking has changed greatly in the last decade. I don’t know how long it’s been since I’ve done a movie that had fewer than 300 effects shots.”

“Filmmaking has changed greatly in the last decade,” Burgess continues. “I don’t know how long it’s been since I’ve done a movie that had fewer than 300 effects shots. Everyone’s thinking has had to evolve in order to facilitate the extensive communication that’s necessary among all the departments involved in every shot.”

One of Burgess’ key tools in maintaining that communication has been the Kodak/Panavision PreView System. “I started using it on commercials just prior to shooting Cast Away (AC, Jan. 2001), and I found it invaluable,” he attests. “The PreView System is a wonderful tool not only for communicating with the lab but also for showing the director exactly what you’re doing and for communicating with different units. It’s also a wonderful continuity tool. From the very beginning, we had three or four different units shooting at the same time on Spider-Man. With the PreView System, I’d shoot a digital still of each sequence we were doing on first unit and then hand those stills off to the other units so that they knew exactly what to match.

trademark suit and tie, directs an effects shot.

“For each shot, I’ll take a reference digital still and send it to the lab along with the film. The next morning, I get the shot back with the printer lights written on it so that I know exactly where I’m exposing the negative. I’m much happier at dailies now that I’ve started doing that.”

Burgess notes that he rarely uses the system for its color-correction abilities, but rather as a shorthand reference for his color timer and additional cinematographers. “At the beginning of the show, I set up specific printer lights on the computer for daytime interiors and exteriors and nighttime interiors and exteriors; those ultimately serve as my reference points, and they don’t change. I keep all of the digital stills in notebooks so we can refer back to them at any time; I can also send copies off with another unit if they need to match a shot. All of the pictures have basic information such as lens stops and filters, and I often add more detail, such as lighting and special-effects information. We also take a grab right from the video tap as a frame-specific reference. We’ll do one PreView shot for each scene, and I’ll do one frame grab for every shot. As a result, we have a wealth of specific continuity information at our fingertips. I wasn’t available for some reshoots on Spider-Man, but the notebooks were there, and that made it much easier to match the additional shots to the rest of the film.

“There’s nothing worse than trying to shoot something for another cameraman based on video clips,” adds Burgess, whose second-unit credits include Backdraft, Batman Returns and Death Becomes Her. “It can be a real nightmare. Now we’ve started using digital cameras and calibrated workstations on each unit. They’ll shoot a still of what they’re working on and send it over to me, and I can look at it right away and recommend adjustments. That way, they know their work will cut in with what were doing. The PreView System makes it much easier to do multiple-unit work, and it’s especially useful on a movie like Spider-Man!’

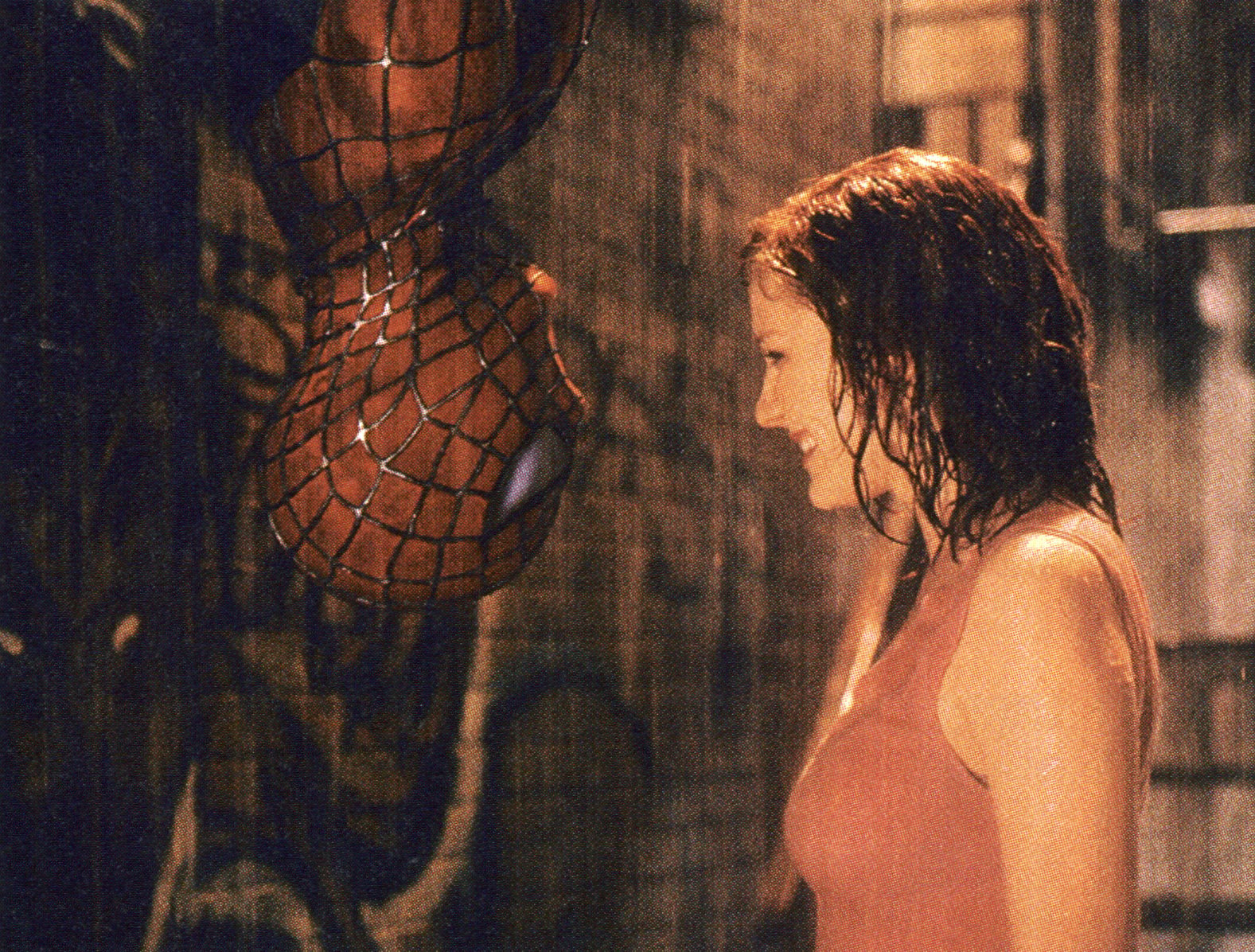

One of the early challenges for the production was creating a Spider-Man costume that would satisfy the filmmakers’ needs and survive the scrutiny of Spider-Man’s fans. Costume designer James Acheson, who won Academy Awards for his contributions to The Last Emperor, Dangerous Liaisons and Restoration, created the web-slinger's uniform. “One of the problems we identified early on was that if his costume wasn’t exactly the right colors, Spider-Man didn’t look like he belonged in the scene,” notes Burgess. “If the saturation was too little or too much for the environment, he often looked like he’d been poorly composited into the shot. We went through a number of iterations with Jim Acheson, and because of the ways in which the colors reacted to light, we finally decided on different costumes for night exteriors, night interiors, day exteriors and day interiors. We had to use a more desaturated suit for day exteriors and a much more vibrant outfit for the night exteriors so that Spider-Man didn’t just disappear into the night.

“Also, today’s superheroes have to look as if they spend most of their time in the weight room, and even though Tobey is in great shape, the costume had to accentuate that to make him become more of a specimen. Instead of bulking up the suit with latex muscles, which would have made it cumbersome, Jim Acheson added more than 120 silkscreened muscle-tone shading details to the suit. It also had a bit of a reflective quality, and I wound up using very large sources whenever I could to bring out that detail. We used 20- by-20 muslins and things of that nature to help the suit really stand out, especially against the night.”

Spider-Man also shows us the genesis of Spidey’s arch-enemy, the Green Goblin (a.k.a. Norman Osborn, played by Willem Dafoe). Norman is an eccentric tycoon and CEO of Oscorp, a cutting-edge technology firm; his son Harry (James Franco) is Parker’s best friend. When an experiment goes awry, Norman is exposed to a dangerous formula that increases his strength and intelligence but also drives him insane. He becomes the Green Goblin, a foe intent on wreaking havoc at every turn.

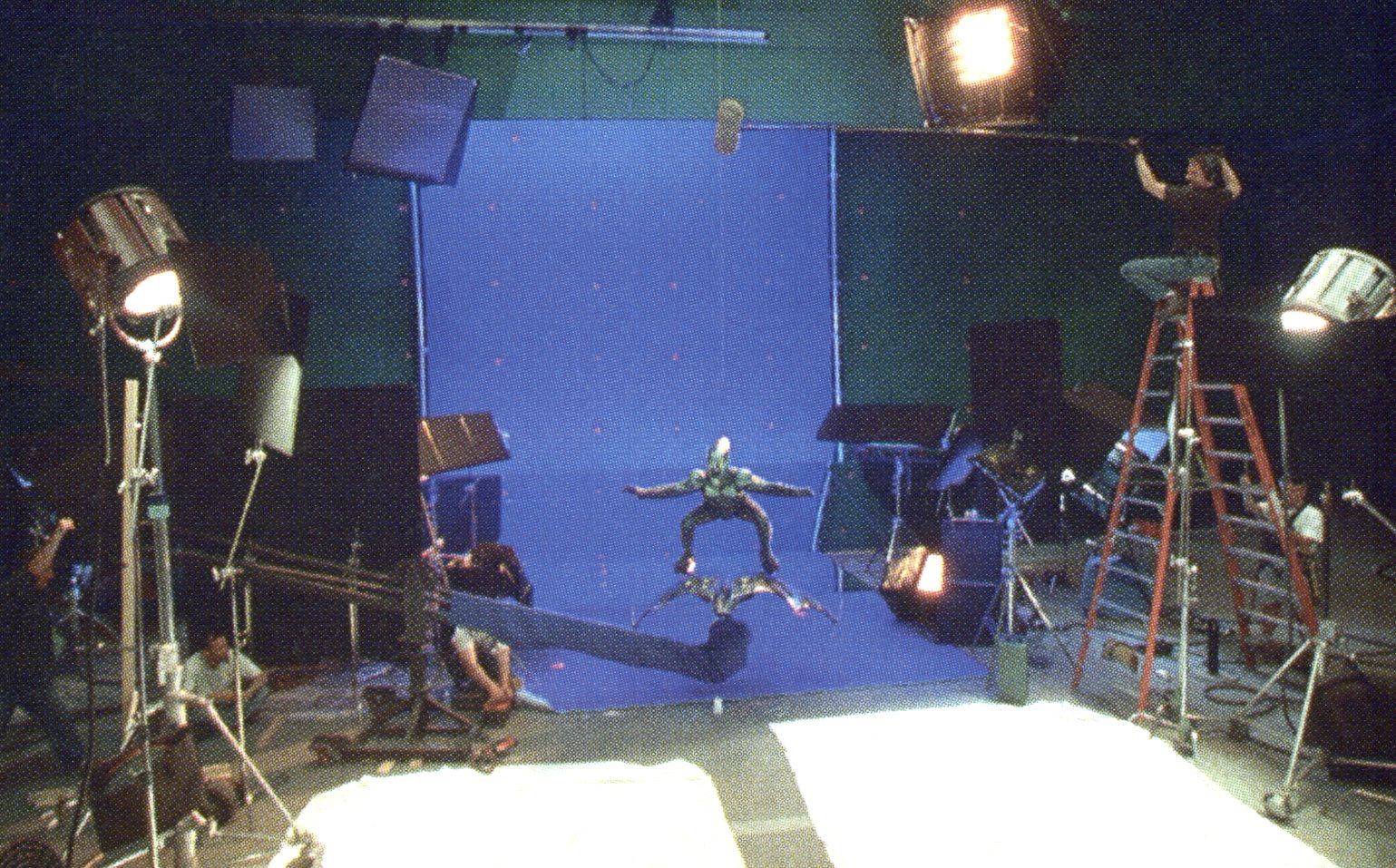

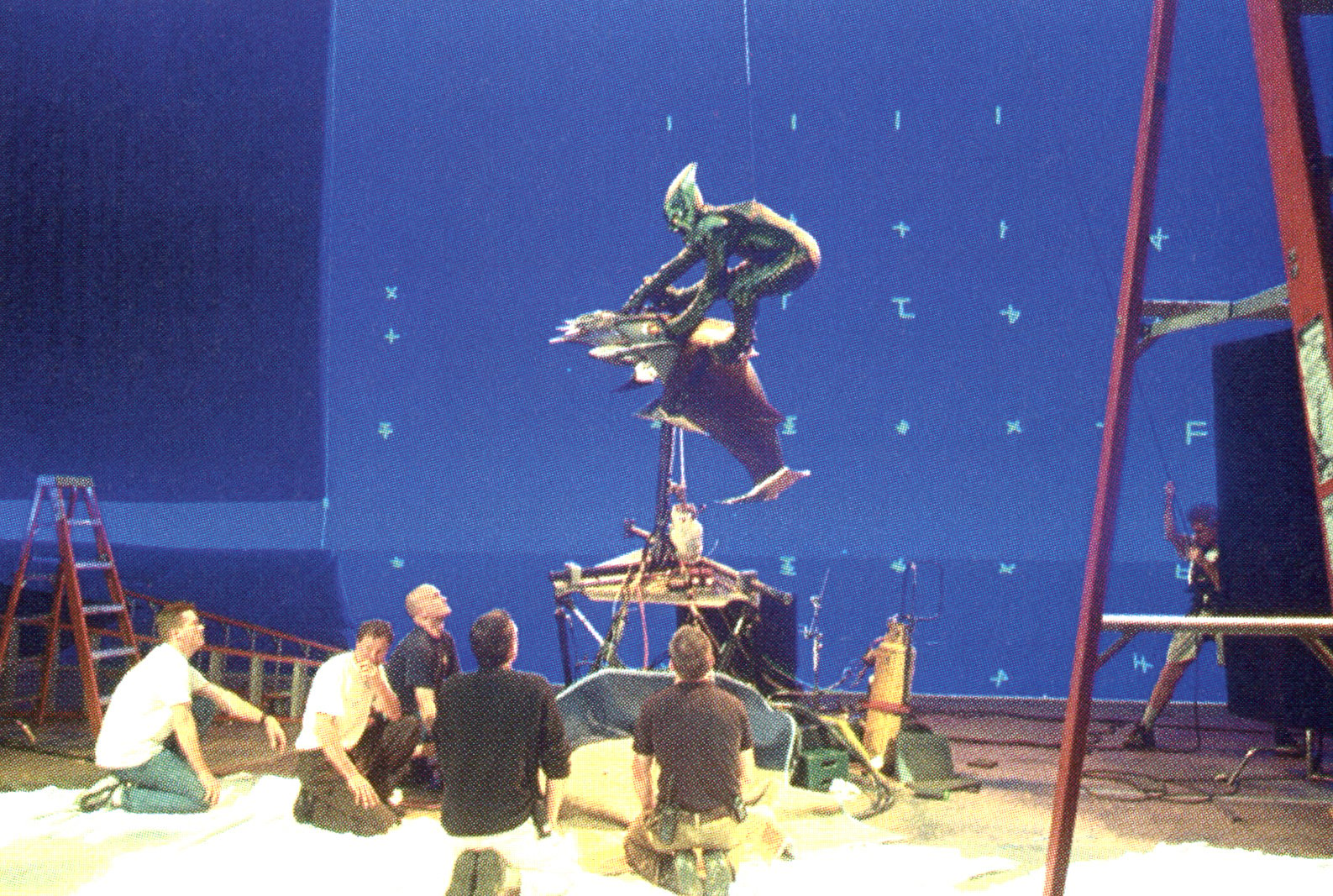

With Spider-Man wearing red and blue and his nemesis clad in a vibrant green, shooting composite elements of the characters in front of a green- or bluescreen became a very complicated matter. “Luckily, those two characters weren’t together very often,” notes Burgess. “When they were, we filmed them both in front of a bluescreen because the Green Goblin costume was more reflective, so it was easier to differentiate the blue of Spider-Man’s costume with the screen and pull the mattes.”

Burgess typically lit the screens with Kino Flo Image 80s with either blue-spike or green-spike tubes, depending on the color of the screen. On the greenscreens, he also used HMIs gelled with Full Green and didn’t correct them to tungsten balance first. Gaffer Steve McGee and his crew placed a Mylar-covered ramp at the base of the greenscreen; the ramp hid the ground row of Kinos and reflected the center of the screen to create a seamless edge on the floor. The crew also used a series of teasers in the greenbeds to mask off the top row of lights and keep them out of the camera’s view. “Because a lot of Sam’s angles were extremely dynamic, we gave him as much leeway as possible by putting up the teasers so we could shoot right off the top of the screen if necessary,” Burgess explains. “We could quickly extend the greenscreen for any shot by adding teasers wherever we needed them.”

“We’ve gotten so entrenched in digital sequences on this film that Sam [Raimi] has created a whole new vocabulary for us: we don’t roll cameras anymore, we commence capture.”

“We used mainly two cranes on Spider-Man,” he continues. “They were the Phoenix, a large crane that gives you a 50-foot reach, and the Felix, a smaller version of the Phoenix that reaches up to 15 feet. We used the Felix on interiors and tighter situations. I tend to always use the remote head because it gives me much more flexibility to create more movement within shots, to adjust shots during takes and to change my mind between takes.”

Burgess shot the majority of Spider-Man on Kodak Vision 200T 5274 stock. “We used a lot of the 200 [ASA] tungsten stock mainly because we could use it inside and out, and it’s very compatible with the SFX 200T visual-effects stock, which we used for all of the blue- and greenscreen shots. Also, a lot of creative ideas occur during postproduction, and to protect the image, it’s best to shoot a stock that will hold up later if it’s enhanced with an effect. I’ve found many times that with a 500- ASA stock, for example, the resulting effects shot wasn’t the kind of image I had in mind. So I tend to shoot the 200-speed stock or lower.”

Burgess kept his shooting stop around a T4 for interiors and a T8- T11 for day exteriors. “I tried to maintain as much depth of field as possible. A large part of the ‘comic book look’ is that everything is in focus from one inch to infinity, so I lit the sets to a T4 at 200 [ISO], and when we went with the wider lenses it worked out quite well.” The cinematographer also used a bit of filtration, a Tiffen White Pro-Mist for interior work and a Warm Pro-Mist for day exteriors. He typically chose filters in the ⅛ to ¼ range.

Visually interpreting Spider-Man was not an easy task, Burgess notes. “On most films, we normally come up with a lens and camera movement concept that progresses with the story, but that was a little tough to do on this project because so much of it is virtual, and it took me a little while to get into the rhythm of how Sam sees the world and how he saw this story. We also had to find the logic of the character's superhuman abilities. Would they do everything twice as fast as a normal person? If so, how do we represent that on film? We started by shooting the action sequences with a wider range of lenses, around the 14mm to 21mm range, to create a more dynamic effect of perspective. The wider the lens is, the faster the movement appears to be, and then you get a sense of speed when the characters are throwing a punch. You go in tighter and slow down the moment of impact to get a more dramatic effect. For the sequences that show Peter Parker as a normal kid, we switched to the more ‘normal’ range of lenses: 27mm, 35mm and 40mm.”

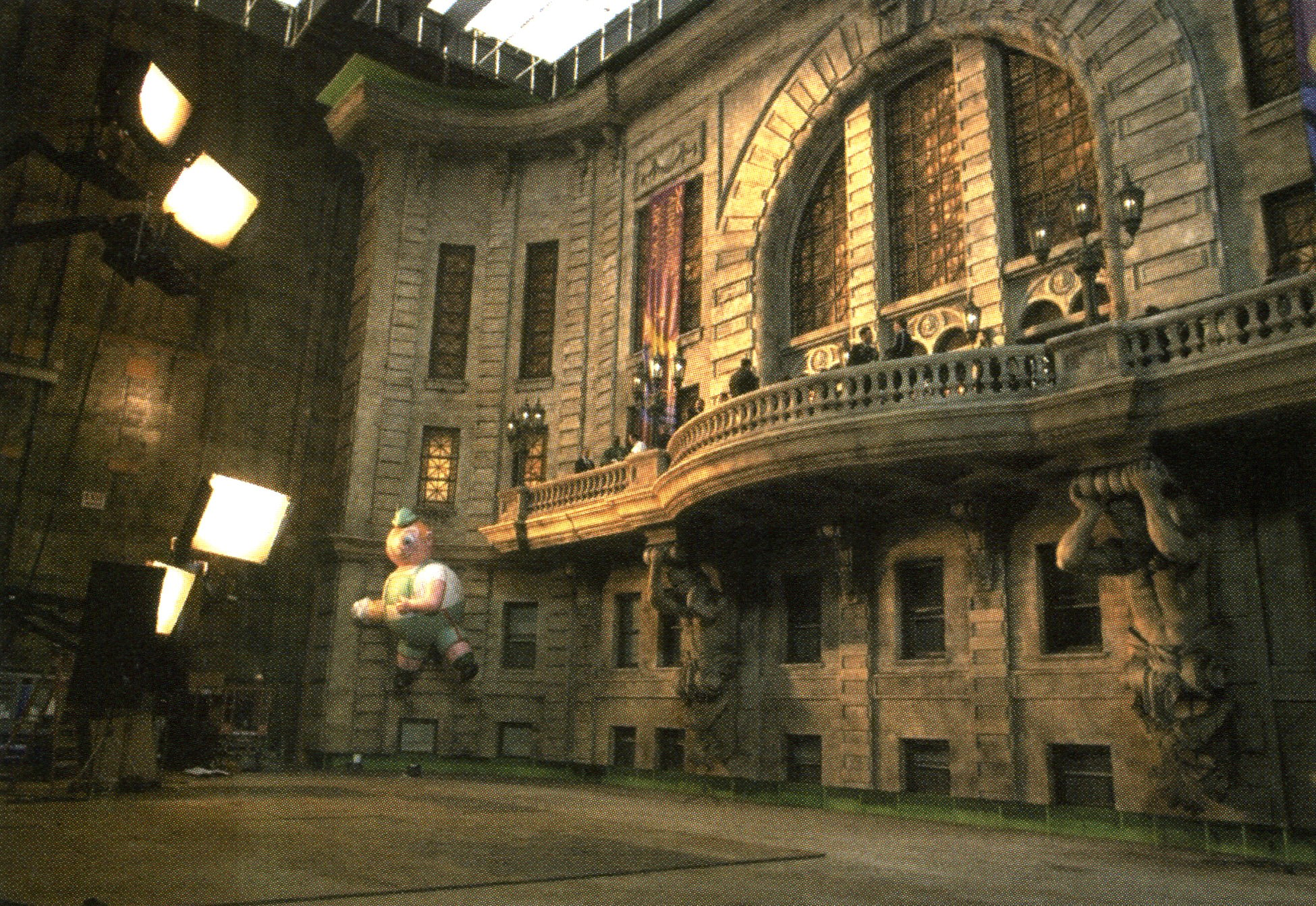

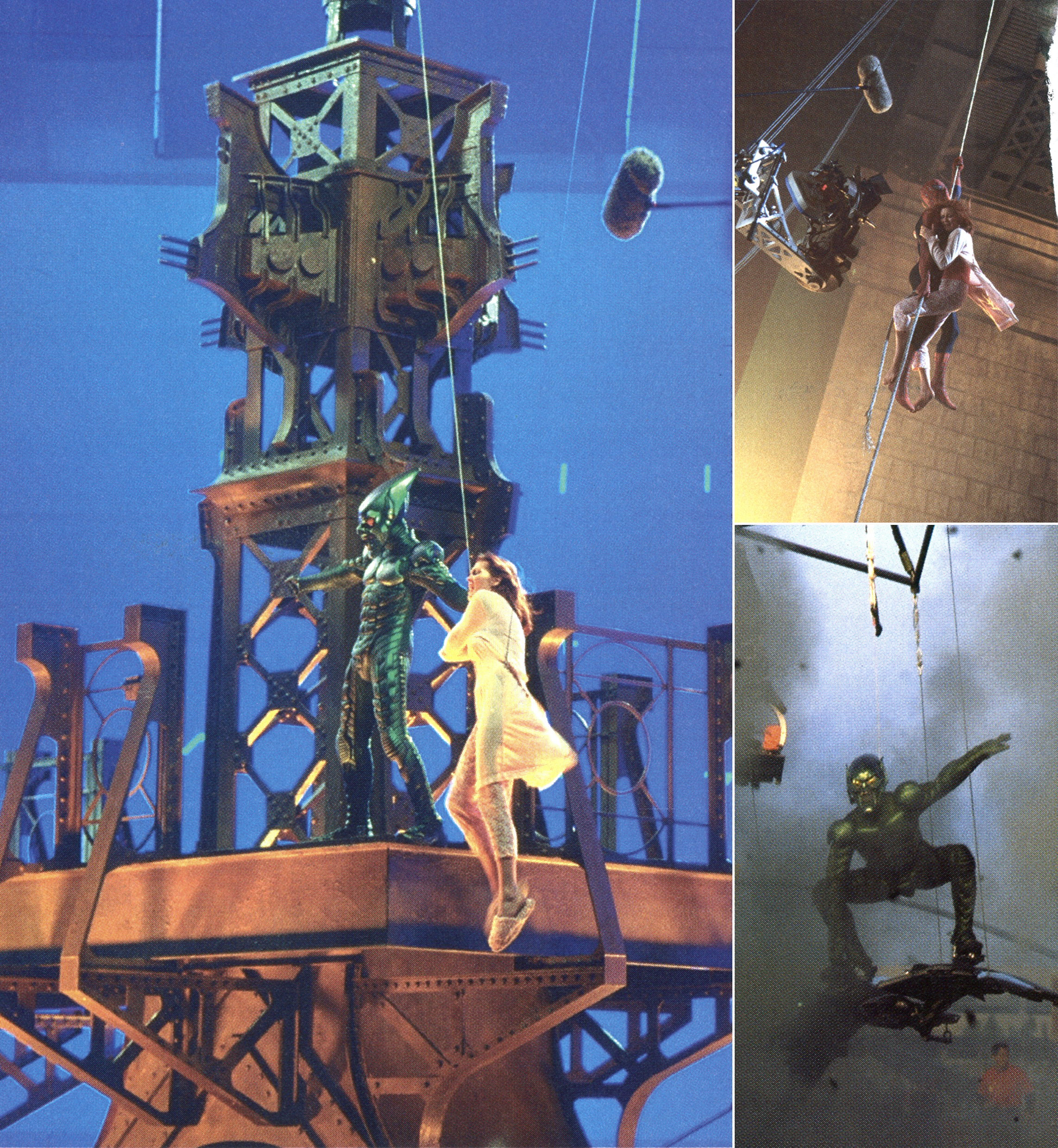

Most of Spider-Man was filmed on stages at Sony Pictures, but the production spent a few weeks shooting in New York to help establish the story’s locations. One of the film’s key sequences takes place in Times Square during the World Unity Festival. During the celebration, the Green Goblin sweeps in and starts to wreak havoc, and Parker must slip off and become Spider-Man in order to save the day. When the Goblin attacks, Mary Jane Watson (Kirsten Dunst), the object of Parker’s secret crush, is standing on the same balcony where Dick Clark does his famous New Year’s Eve telecast. The balcony collapses, and Spider-Man has to come to her rescue.

Realizing the complicated sequence required a number of different elements and different locations. “Planning this kind of sequence is very tedious,” Burgess says, “and I’ve always got to begin by finding something to hang my hat on. For the Times Square sequence, I started with photo studies.” Shooting stills every 30 minutes from dawn to dusk on rooftop locations surrounding Times Square, Burgess was able to determine that 4:30 p.m. would be the optimum time to film the scene. “That hour was perfect from a lighting standpoint. The sun is just low enough that it rakes down the alleys of some of the buildings, giving us warm sidelight along with the cold, afternoon skylight and the cool shadows at the base of the buildings. I knew I could recreate that look no matter where we went.

“We then tried to figure out how we were going to tackle this sequence,” Burgess continues. “The battle that ensues between Spider-Man and the Green Goblin is really an aerial battle. We started with a number of aerial plates shot with Cable Cam-style rigs in Times Square, and then started looking for a stage where we could build a set. We looked at the Spruce Goose hangar [in Long Beach, California], but it just wasn’t big enough. Our visual-effects supervisor, John Dykstra [ASC], needed camera angles from 140 feet up to make all of the plates work properly. We finally realized that we weren’t going to find a stage big enough to facilitate that, so we built a replica footprint of the building in the parking lot of the former Boeing plant in Downey, California. We flew two 60-by-120- foot silks from construction cranes over the set and brought in Condors with about a dozen Dinos lamped with 3200°K Firestarter globes to recreate the warm sidelight, and I added a bit more overall warmth with a Warm Pro-Mist on the lens.”

Additional elements of the sequence were shot on Sony’s Stage 27, where a replica of the Times Square balcony was constructed and rigged to collapse. This time Burgess recreated the soft overhead daylight with 6K Spacelights, and he brought in the Dinos for the raking backlight. Backings for this sequence included blue- and greenscreens, as well as TransLites made from photos taken at Times Square.

Another tricky sequence — also a battle between Spidey and his nemesis — takes place atop New York’s Queensboro Bridge. Production designer Neil Spisak recreated the bridge’s pilings on Stage 30. “Neil was essentially bringing the scale of the city onto the stage by taking a small element of [the structure] and making it appear as large as the real thing, if not larger,” Burgess explains. “Those sets were probably the biggest I’d ever shot.” For the bridge’s background, Burgess opted for painted backings. “It’s a pretty dark night sky, so we used the painted backing to add a little bit of texture without kicking the cost of the sequence through the roof.

“We first see the Green Goblin in a golden light because he’s in front of a very warm fire,” Burgess continues. “I tried to keep that motif for him throughout the picture, so I lit the bridge with a sodium-vapor look using tungsten lights gelled with Lee Apricot (#147) and Straw (#103). That looked great on both costumes, and we tried to keep it as backlight around the action. We generally kept the fill sources clean white. We lit the Goblin’s costume the way we lit Spider-Man’s, creating specular reflections with large a 20-by-20-foot muslin bounce.”

One of the film’s early sequences was shot at a practical location in Los Angeles: the Museum of Natural History. The museum was standing in for the lab where Parker is bitten by the spider. The museum’s ceiling is a large, circular skylight, and the crew masked it off and floated two 10K lighting blimps inside to create a soft source that would cover the whole room. Burgess then augmented the overhead light with Kino Flos and regular fluorescent sources placed on the floor around the actors.

“It’s a fun scene. Ultimately, Parker has to call upon some of his Spider-Man ability to stay alive.”

Shortly after discovering his new powers, Parker decides to make some quick cash by entering an open wrestling competition. He finds himself in a giant cage, face to face with Bone Saw McGraw (played by World Wrestling Federation superstar “Macho Man” Randy Savage). “They bring down a giant cage that goes around the ring so that Peter can’t get out, and they put him in there with a pro wrestler who’s about three times the size of Tobey,” Burgess says with a chuckle. “It’s a fun scene. Ultimately, Parker has to call upon some of his Spider-Man ability to stay alive.

“The idea was to make it as cheesy as we could — the cheesier the better. We basically created a whole stadium and did what I call ‘disco lighting,’ which is theatrical stuff. We threw up spotlights and runways and just had fun; we brought in a bunch of Intellibeam sources and just had them go crazy. They’re a lot of fun to work with because they can do so many different things — you can swing them, spot them, change the color, flood them and create different patterns, all on the fly. You can also program them so that you can repeat the same look over and over for each take.”

Of course, one of Spidey’s most famous attributes is his ability to crawl up and down buildings the way a spider would. A gravity-defying effect is typically achieved in films by laying the set and camera on their sides to make it appear as though the shot is vertical. Spider-Man special-effects supervisor John Frazier and stunt coordinator Jeff Habberstad took this technique further by suspending Maguire from the set on wires so that he could move about completely weightless on the seemingly vertical surface.

When it comes to incorporating CG effects into live-action footage, Burgess reaches for interactive elements as often as he can. “I do as much interactive lighting for CG elements as I can because it always helps,” he says. “In this film, we have a lot of [CG] fires and explosions, and I always try to have something happening in the foreground, which helps to sell the effect. The Queensboro Bridge sequence features a CG shot of the Green Goblin making a fly-by, and I made sure to have a spark effect hit so that as he flies by and hits the bridge, we set off a big spark and flame. Mary Jane is perched on top of the bridge as he swoops by, and the practical effect gives her something to react to. By doing that, there’s much more energy in the shot. I’ll also throw in fixtures on dimmers as often as I can, like a Maxi-Brute with some Firestarters, to accentuate an explosion. It helps everyone in the scene react to something more concrete, and you get a better feel for the action when you’re shooting.

“We’ve gotten so entrenched in digital sequences on this film that Sam [Raimi] has created a whole new vocabulary for us: we don’t roll cameras anymore, we commence capture,” Burgess adds. “Sam was really the reason I signed onto this project, and I’m very excited about what we’ve done. It became a matter of how far we could push this idea visually. We said, ‘Let’s make it feel like this could really happen,’ and it became a matter of taking the cartoon out of the book and putting it into real life. Spider-Man is real life with an edge.”

1.85:1

35mm Panavision Platinum and Millennium XL Primo lenses

Kodak Vision 200T 5274, SFX 200T

Print Stock: Kodak Vision 2383