Steven Spielberg and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

The director discusses his inspirations, creative process and collaborating with Allen Daviau, ASC and Dennis Muren, ASC on his 1982 sci-fi fantasy classic.

About 32 years ago, Howard Hawks produced The Thing From Another World, a masterful film about a malevolent being from another planet wreaking havoc at a far outpost of our earth. The title character, portrayed by James Arness, not only scared the daylights out of millions of patrons but instilled in them a distrust of anything from “out there” as they heeded the warning spoken at the close of the picture: “Keep watching the skies!”

Producer-director-writer Steven Spielberg changed all that some years ago with Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a highly successful film about benign visitors from outer space. Recently he went a step further and brought to the screen an alien being that is not only benign but lovable — a strange little creature known only as E.T. The picture in which the being appears is E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which has been the most talked about and financially successful film of the past year.

Already a “cult” film, E.T. will, in all probability, become a perennial audience favorite like a mere handful of fantasy films such as King Kong and The Wizard of Oz.

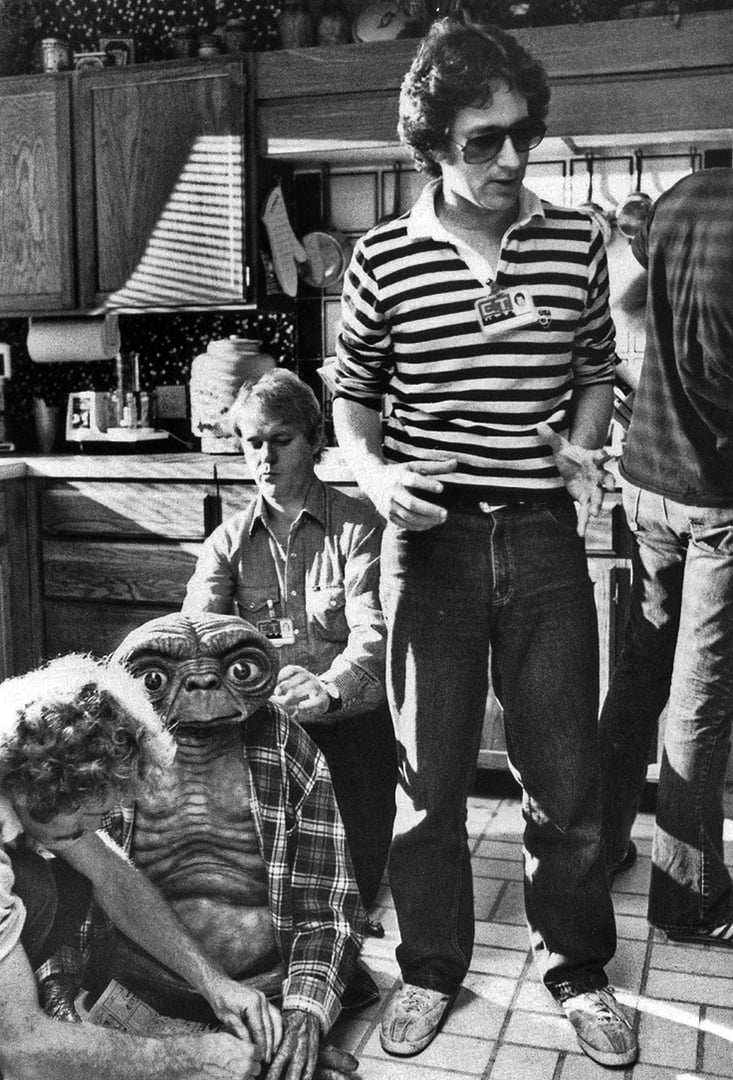

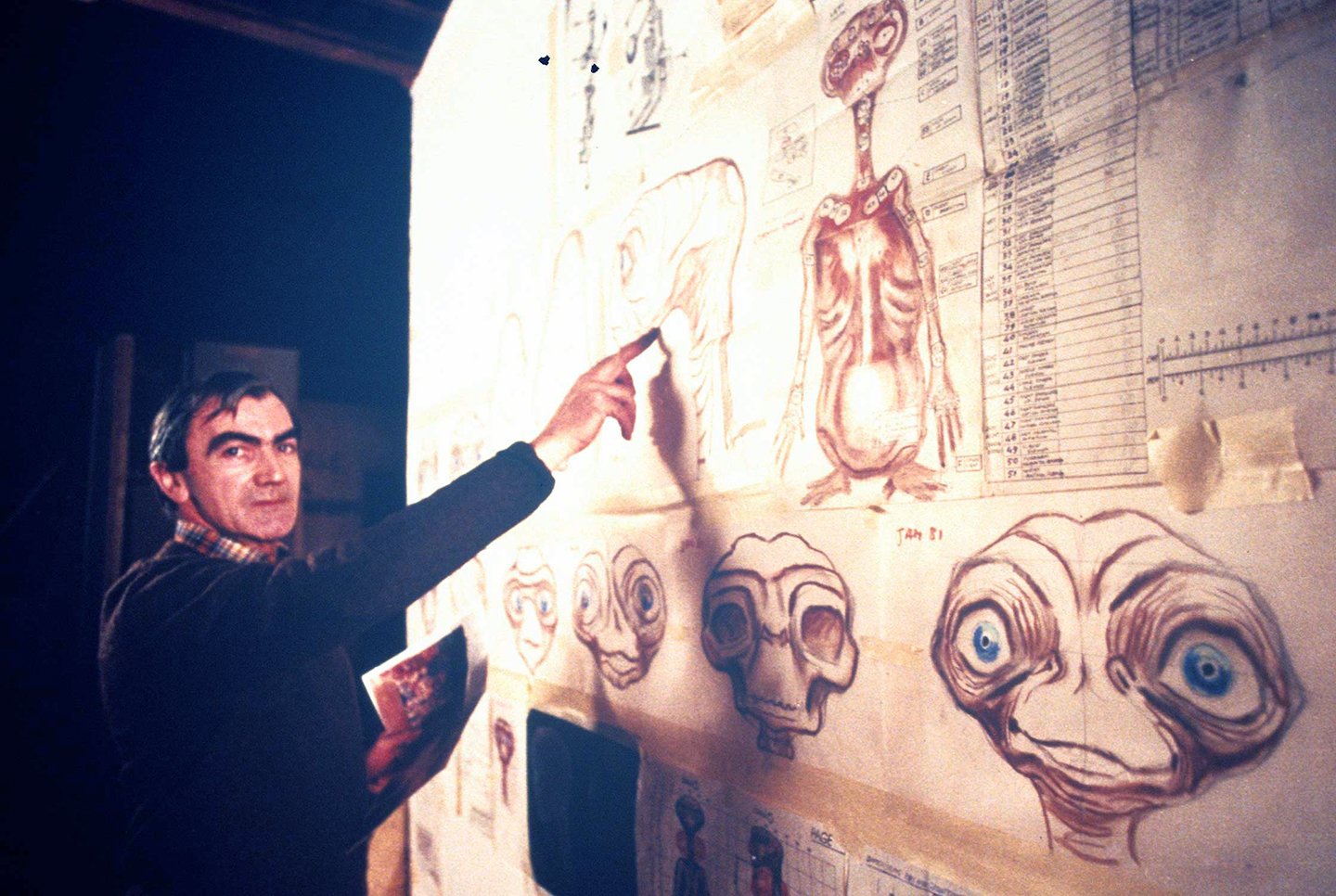

As for Spielberg himself, he is a pleasantly eloquent young man in his mid-thirties who first gained attention with his direction of a segment of Night Gallery and the TV feature Duel, gained fame with the celebrated Jaws, and has flourished as one of Hollywood’s top filmmakers with Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1941, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Poltergeist. That he has managed to invest E.T. — a mechanical being engineered by Carlo Rambaldi — with a charm and personality achieved by few real performers — is a remarkable achievement.

“I don’t think anything in film comes to anyone in a blinding flash,” Spielberg said when American Cinematographer asked how he was inspired to create E.T. “Creative people in art or architecture or filmmaking or theater or writing are all products of a collection of impressions from our earliest memories. I don’t think there is such a thing as a cathartic flash of white genius light — that’s a popular myth. We’re all inspired. I’m inspired all the time, but my inspirations are a sum of all my parts, and all of my parts started back in 1947 when I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and kind of accumulated the dust or the pollen of my experience right up until E.T.

“So, I can’t really say that E.T. dropped out of the sky and hit me on the head without a number of experiences from the time my father made me go with him at two o’clock in the morning to watch a meteor shower when I was six years old and I suddenly realized that the sky up there and the stars are worthy of closer scrutiny, all the way to the time I saw The Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan and every Disney film ever made and all the films of Hitchcock and Kubrick and read all the novels of Steinbeck and Faulkner and all the experiences I ever had in elementary and grammar school and high school and college to bring me to a place in my life where I found myself standing out in the Sahara Desert shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark and, indeed, something did fall out of the sky and hit me on the head in the shape of a small, fat little squashy character named E.T.

Spielberg had high praise for the work of cinematographer Allen Daviau, his choice for E.T. “It was a choice I had made once before when I was a student at Long Beach State College. I wanted to break into the film business and my 8mm and 16mm films weren’t doing the trick — the studio heads and producers weren’t looking at 8mm in their offices anymore — so I raised some money from a young man who wanted to be a producer, who had the same burning desire to produce as I had to direct. He had an optical company and he could afford $10,000 toward a film. It was a film called Amblin’. I had worked with Allen Daviau on a short film that was never finished called Slipstream, which was about a bicycle race starring Tony Bill made when I was about 18 years old. That film was shot by a director of photography named Serge Haigner, but Allen Daviau assisted him and Allen and I became pretty good friends. I offered Allen a chance to D.P. Amblin’, so it was a pretty big break for both of us.

“I really liked Allen’s work in Amblin’ because his work in that was as slick as my work was and Allen and I are proud of the movie in different ways. I like Amblin’ because it worked and got me into the film business and Allen liked it because it was shot in 35mm. I don’t know how crazy we are about our individual work in that film, but I always think of Allen as a terrifically versatile cinematographer who can do anything with light and shadow. I’ve worked with some of the greats. Bill Fraker [ASC] probably has been one of my greatest experiences on a movie studio floor or on location, and Vilmos Zsigmond [ASC] was very fulfilling to work with, and yet I didn’t want to work with a high profile cinematographer on this. I wanted to work with someone who was a little hungry, hadn’t done a theatrical feature before, was going to make an audacious first impression, and was going to help bring this picture in for ten-and-a-half million dollars and no more than 58 shooting days. I just didn’t know if I could get any of the guys I’d worked with before to shoot an adventure film in 58 days. I thought I could probably get Fraker to do it; Billy can shoot very quickly with great quality, but he was busy at the time. I remember approaching Billy first and he was working on something and really wasn’t available when I needed him. I offered the film to [Vittorio] Storaro [ASC], but he was just coming off of One From the Heart and he was very bitter about his experience in having to take a lighting design credit and not being able to get the director of photography credit because of the bylaws of the IATSE. He just didn’t want to make another picture in America and I was willing to fight for him, but he wanted to go back to Italy and work for Bertolucci and he was sort of fed up with the whole Hollywood business.

“Well it was the darndest thing, I was watching a TV movie [The Boy Who Drank Too Much] and it was something Allen Daviau had photographed. I was really impressed and I did something that I rarely do, I didn’t think twice: I picked up the telephone that night and phoned Allen and said, ‘Would you photograph my next feature?’ There was a rather stunned pause on the other end of the phone and Allen said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘I just saw something on television which knocked me out and I’d love for you to work on this.’

“Allen and I had decided long ago, before we ever did any concept sketches, I didn’t want to show E.T.’s face for about 25 minutes — that’s the way I wrote it in the script. Yet E.T. and his friends are on the screen from the second or third shot of the picture. I didn’t want to see his face until very late in the first act of the movie, and that probably gave Allen his biggest challenge. We would see him in silhouette, we would always view him in backlight, but you would never get a good look at his face until much later in the movie. It took many, many small, small units of light and many pieces of aluminum foil to use as bounce cards. We were really able to mold light with E.T., but you couldn’t do it in the master shots or the lights would show. And E.T. was really limited in movement when Allen had to make him more mysterious. It took a lot more time to light E.T. than I did to light any of the human beings in the movie, and I think Allen spent his best days and his most talented hours in giving E.T. more expressions than perhaps Carlo Rambaldi and I had envisioned, because he found by moving a light, by moving the source of the key from half-light to top-light, E.T.’s 40 expressions were suddenly 80. E.T. could not only look sad but he could look curiously sad. Not by the way we controlled E.T. mechanically but by the way Allen shifted light.”

Another necessary aspect of the film was to keep the viewpoint that of a child. This meant, Spielberg recalled, “that the camera was always on the Fisher dolly and the lens was usually around four feet, eight inches in the air. There are a lot of ceilings in the movie because so often a child’s point of view does look up, especially Elliott’s point of view of his older brother. I’d always drop the camera a little lower because that was Henry Thomas’s point of view, and E.T.’s point of view was even lower than that, two feet, nine inches off the ground. For this and other reasons I chose not to show faces of adults except for Mary, the mother, because I didn’t really consider her an adult, I thought of her as one of the kids in that household. She was just like anybody else who could keep a secret. But I avoided showing the biology teacher, avoided showing any of the policemen or any adult strangers until the very end of the movie, when you finally were confronted with all the doctors and scientists.

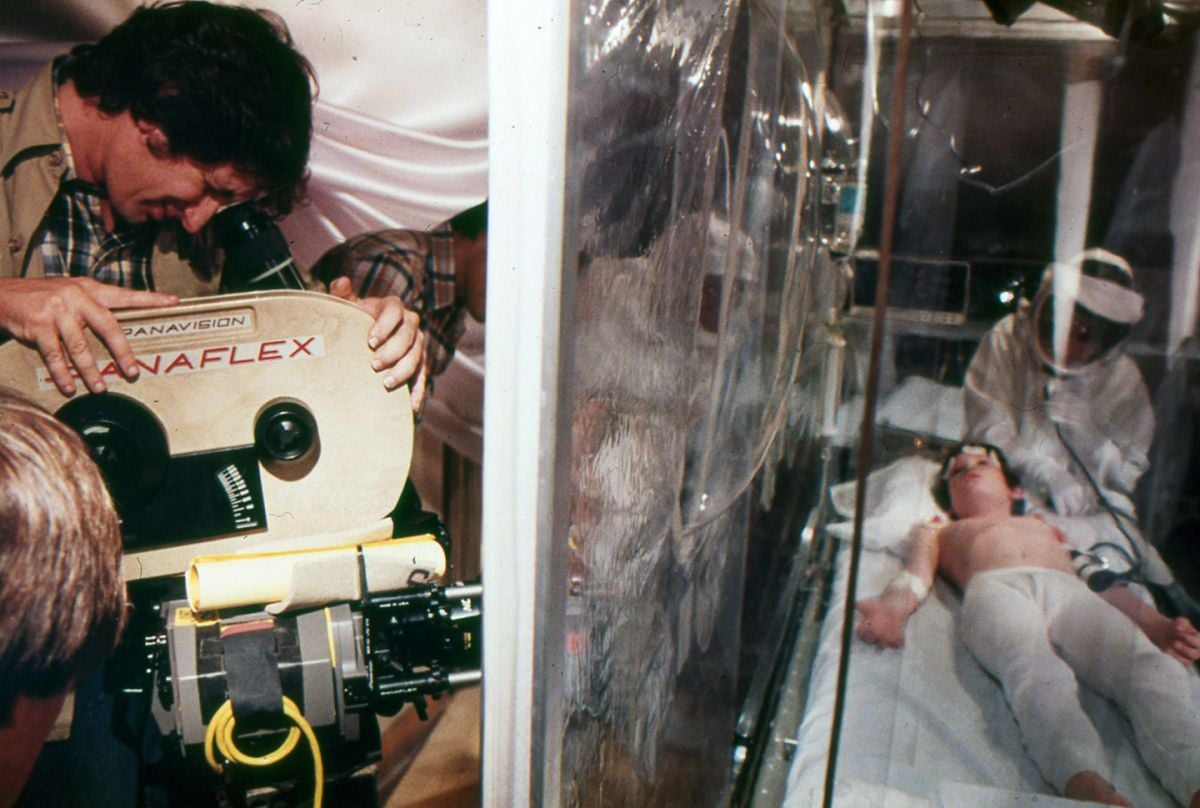

“Very early in our relationship we discussed concepts of lighting style. I wanted the movie to look very realistic, meaning that if it’s 10 o’clock in the morning the sun’s going to come directly through both windows and blinds of Elliott’s bedroom and they’re going to be very hot in contrast to the rest of the room, which would be dark to the taste of the kids — Elliott’s taste as a little boy growing up in suburbia, with all the trappings of suburbia, such as the dark posters on the wall and the electronics on the work table. So we went for a very extreme key to fill ratio in lighting most of the scenes at the beginning of the picture, but we reserved the closet where E.T. makes his home as a kind of magical wonderland. We took great pains to stylize all the shots inside the closet; for instance, it was Allen’s idea to put a yellow neckerchief over the lamp in the closet to bask everyone in a kind of whimsical sunset. I wanted a stained glass window in the closet to be able to justify spattered colored lights. This continued the magic of E.T. in the only place he’s going to be able to call home for the next couple of weeks, so we decided to really let the closet be the magical hideaway but let every other room in the house be brutally dramatic and not suggest that we were making a picture about contemporary fantasy but, in fact, we were making a movie about contemporary suburbia and all the visual reality suburbia seems to invite. But the closet was magic, and then we decided conceptually that once the scientists and doctors occupied the house and the front and backyards we would go for a rather antiseptic white on white AMA look.

“A lot of that was due to a fantastic production designer, Jim Bissell, who really helped our concept in somewhat ‘painting’ everybody white on white, from Deborah Scott’s environmental protection suits, which were white or a very pale blue — what we called the clean room suits — to the scientific hardware which Bissell assembled and the actual clean room environment with the see-through, clear plastic shower curtains and the clear plastic that was embroidering the entire living room, dining room and kitchen, which had been turned into a field hospital from an ordinary Hot Point kitchen. You could almost smell the antiseptic.

“He lit everything where you can see the lights. The lights that help to light the antiseptic clean rooms are actually in the picture — they’re clip-ons on top of the clean room area. Allen was very conscious of what kind of day it was and he kept pressuring me to give him the exact time of day when each moment took place inside the clean room, because that would certainly affect what kind of light seeps through the windows which are covered over by many layers of clear plastic. That had a dramatic effect, like in the scene where E.T. dies and Elliott says goodbye to him, that is a very early morning; there’s almost a pale red coming from the two windows behind Henry Thomas as he bids his final farewell to E.T. As the day progresses the reds were removed and the windows became warmer and then suddenly they became suddenly hotter as you lead into a late-afternoon chase.

“We don't really pay very much attention to how long it takes Elliott to evacuate E.T. from the clean room and into the Econoline van. But we do abbreviate our day, because by the time we were on the road and escaping the police it's late afternoon with dust rapidly approaching. We take some time license with that part of the movie, but it was very important, I thought, to suggest a pinkish color to the goodbye scene with E.T. Allen was very, very aware of time and even how time moved. The look of Elliott's bedroom when the mother puts him to bed when he's feigning illness and sticks a thermometer in his mouth, that's before school starts, about 8:30 in the morning, so the sun is very strong through all the layers and hitting everybody. By the time school's over and Elliott’s brother Michael comes home and Elliott shows Michael E.T. for the first time, the entire source of the sun has shifted and it's no longer coming from the windows over Elliott's bed, it's coming from the windows by the workbench, so the sun has gone across the sky. Allen was very time conscious about the source of the sunlight.

“There aren't many pictures that all take place in a child's bedroom closet, and I'm used to painting on a large tapestry. Condensing the story to human people and to extraterrestrial people and to a closet environment suddenly got me thinking we don't have a thousand extras to paint my canvas with but we do have light, we do have the sun, and we do have a kind of color texture to work with, let's let the lighting give the movie the production value. So in this movie, more than most of my films in the past, lighting really supplies a lot of value. Lighting puts money on the screen more than background extras or numbers of cars. I think as a director I was more conscious of lighting on E.T. than I have ever been on any other movie before. Especially where E.T. was concerned, because the lighting on E.T. was very important.

“You saw only the back of the principal’s head and shoulders and hands, but you never saw his face. It has Harrison Ford and he consented to do a day for me, but that scene never made it into the final movie. So I owe Harrison about seven more close-ups on the next Indiana Jones feature, which starts in April.”

E.T. is more of a personal film for Spielberg than is Raiders of the Lost Ark, which he directed for producer George Lucas. “Raiders, for me, is more George Lucas's dream that I realized because George stopped making movies, at least temporarily. It's something I wouldn't have come up with — I never would have thought to make a feature version of a Republic serial, you have to leave it to George Lucas to think of something like that. I'll always consider Raiders to be my film as a director but George’s film as a creator. The one thing we always have in common is that we just love audience movies, slightly taller than life.”

Other Spielberg films have been extensively storyboarded before principal photography was undertaken. E.T. is the one exception. “I decided that storyboards might smother the spontaneous reaction that young children might have to a sequence,” Spielberg explains. “So, I purposely didn't do any storyboards and just came onto the set and winged it every day and made the movie as close to my own sensibilities and instincts as I possibly could.”

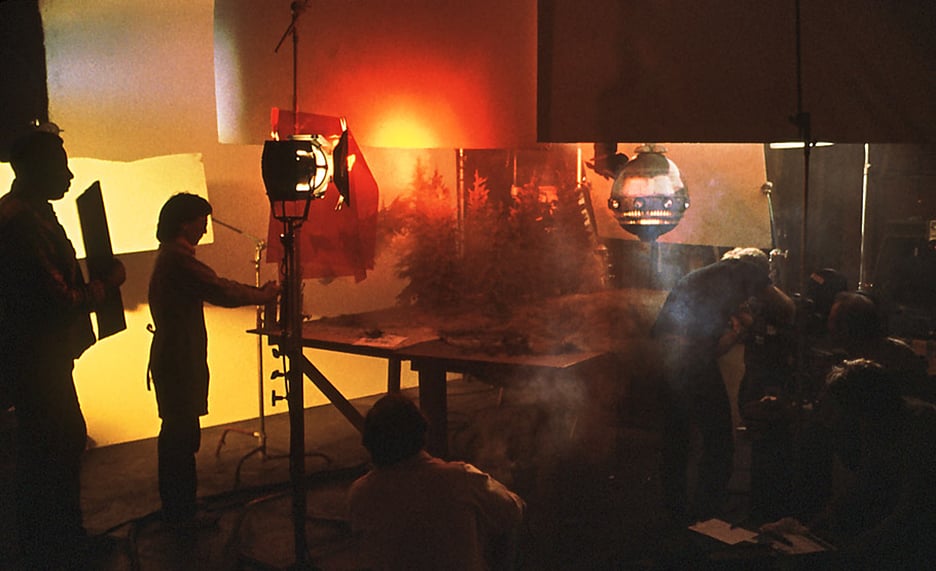

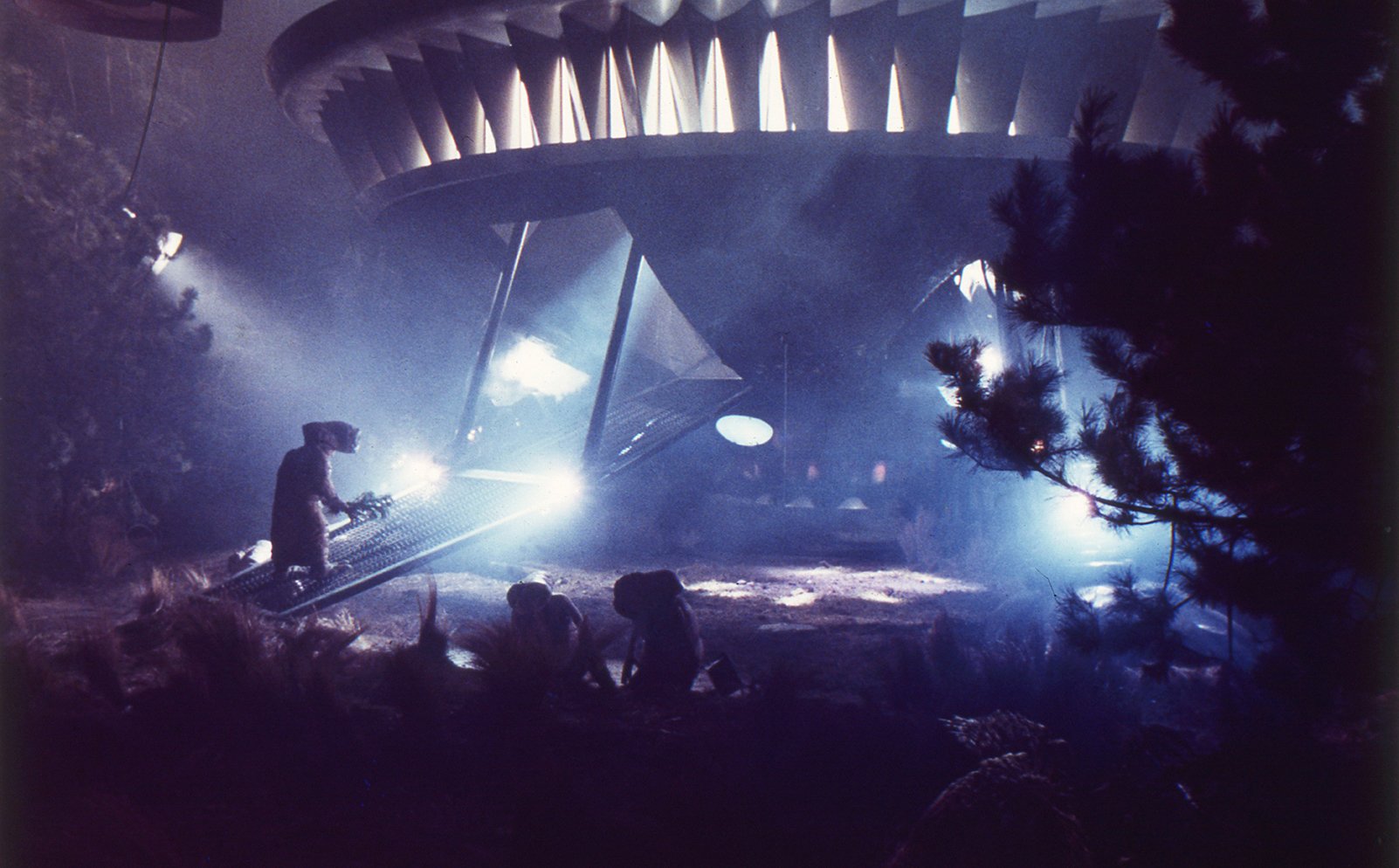

This did not apply to the special effects scenes which were done under Dennis Muren [ASC]’s supervision at Industrial Light and Magic in Marin County, California. In this specialized area storyboards are essential, according to Spielberg.

“I did storyboard about 45 special effects shots because ILM is paid by the shot and it's very important that you are specific right down to where the light is coming from and write down to the exact frame count for the shot. You can wait for the muse to strike on a soundstage if you're responsible for the ultimate schedule, but where ILM or any special effects shop is concerned, every shot cause X amount of dollars. Often they’ll give you a handle on each side of the usable portion of the shot, but even the handles start to cost money. Because Kathy Kennedy and myself were trying very hard to make this picture for under $11 million and — of course, we succeeded in that.”

“Dennis Muren is an artist as well as a technician, and he has a way of flavoring each shot so that it gives you more than originally imagined. Dennis would always add so much more to each concept to make the shots really come to life. You know, concept is only a battle plan, but there is an individual effort given by everybody who works in the special effects. They're dedicated, and their love shows.

“We kept driving for a reality. The fantasy was a concept, but the reality was what sold it. The concept of flying bicycles is a fantasy right out of our 8-year-old dreams, but the concept of how real the sun should look and how much would it flare the lens — that's the reality that sold the shots.”

The Spielberg approach differs substantially from the way most fantasy films have been done in the past. The producers of The Wizard of Oz, The Bluebird and Peter Pan deliberately re-created an atmosphere reminiscent of the great fairy tale illustrations of Rackham and Dore, but Spielberg wanted nothing of Never-Neverland in E.T. “I mean, midday clouds are white, not purple. I just think if you’re going to have to go find some clouds the clouds should be white. It's very important with E.T. that everybody who saw the movie believes that E.T. could come into their backyards and walk into their homes to visit their children. You really can't do that if you set the stage for storybook unreal. I think you have to get just the opposite. I work very hard to juxtapose a kind of contemporary suburban or urban truth on fantasy images.”

Spielberg emphasized the importance of editing in creating the realistic fantasy he wanted. “I worked with a new film editor, a woman named Carol Littleton, who made countless fantastic contributions in post-production to the assembly of E.T. She's one of the few editors I know who cuts to music, and she selected some fantastic music for our temp tracks to cut to. She found some Shostokovich, which she cut the first movement of the film [the chase in the forest], and Howard Hanson's romantic symphony which we paced the final ‘goodbye’ scene to, and even some of the soundtrack from Hal Ashby's film Being There — some of that wonderful music by Johnny Mandel. We were very successful in putting some of our images to music and then taking the music out so Johnny Williams could have a fair shot at imagining his own themes. Carol is a wonderful film editor, and she works long, hard hours. She's a genius at rhythm, at a frame off and adding a frame here or a frame there. She's just one of the best experiences I've had in the editing room. I feel very, very honored to now have worked with three of the best film editors in the business: Verna Field, Michael Kahn and Carol Littleton.

“Also, this was a triumph for new faces. We had so many first-timers on E.T. We had a majority of women working key positions on the crew and in administrating, from Melissa Mathison, who wrote the script, to Kathy Kennedy, who co-produced it with me, to Katy Emde, who was the first assistant director, to Deborah Scott, who did the costumes — there were so many women in positions often, in the past, filled by men. It felt very womb-like going to the set every day.

“It was, un-technically, Allen Daviau’s first feature — he had made a film in Canada — but it was his first theatrical feature film. It was Jim Bissell’s first theatrical feature as a production designer and art director. It was Kathy Kennedy's first feature as a producer and Melissa's first feature as an associate producer.”

One thing that amazes Spielberg is that so many patrons return to see certain of his productions over and over again. “It's kind of like playing video games. A kid plays a video game and he receives a perk for his quarter, so we put another quarter in for another perk, and of course it's a series of diminishing perks because once he conquered the idea and once he overcomes the challenge of the game, he goes on to other games. I hate to compare movies to video games; in a way with repeat business it's a fair comparison, it's one of the few comparisons around. People go to a movie to be entertained, but they also would love to have some measure of control over the experience. It's a phenomenon to me why these people see movies more than twice. I get letters from people who have seen Raiders 20 times and E.T. 30 or 40 times and I don't answer their mail because I'm not a qualified shrink.”

On the other hand, Spielberg admits he likes to see certain favorite scenes again. “I look forward to seeing the fragmented moments, like in The African Queen I always liked the sequence with the leeches and I like the sequence where they hit the falls for the first time and have to maneuver their way out. It doesn't have to be the whole movie you yearn to re-experience, it can just be precious, highly prized antiquities left over from a film in your memory.”

Spielberg sometimes likes to include an homage to some favorite old movie scene in his pictures. One such gesture honored stuntman Yakima Canutt’s famous fall under the racing stagecoach in John Ford’s 1938 Stagecoach. “We did a version of that stunt in Raiders of the Lost Ark when Terry Leonard, doubling for Harrison Ford, falls off the bumper and grabs the universal joint of the truck and goes hand over hand all the way down to the tail bumper, where he uses his whip to climb back on. That was a Western homage, a variation on a Canutt theme.”

You'll find a companion story featuring cinematographer Allen Daviau, ASC's take on making this classic film here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.