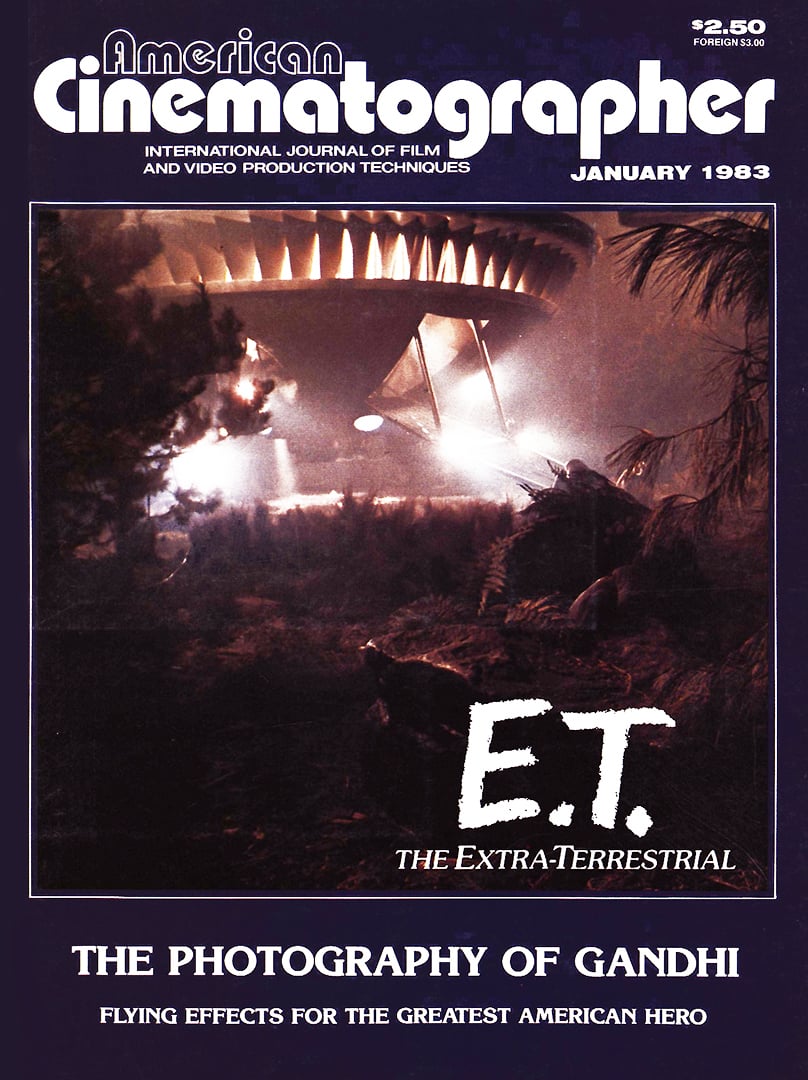

The Cinematography of E.T.

Allen Daviau, ASC discusses his visual approach, techniques and collaboration with Steven Spielberg on this 1982 sci-fi fantasy classic.

It is well known in the motion picture industry that any successful picture owes much of its achievement to its cinematographer. This is doubly true if the story deals with fantasy and yet must be presented in a convincing, realistic manner. Such a film is E.T., which has proved to be the most talked about and widely seen theatrical venture of the past year.

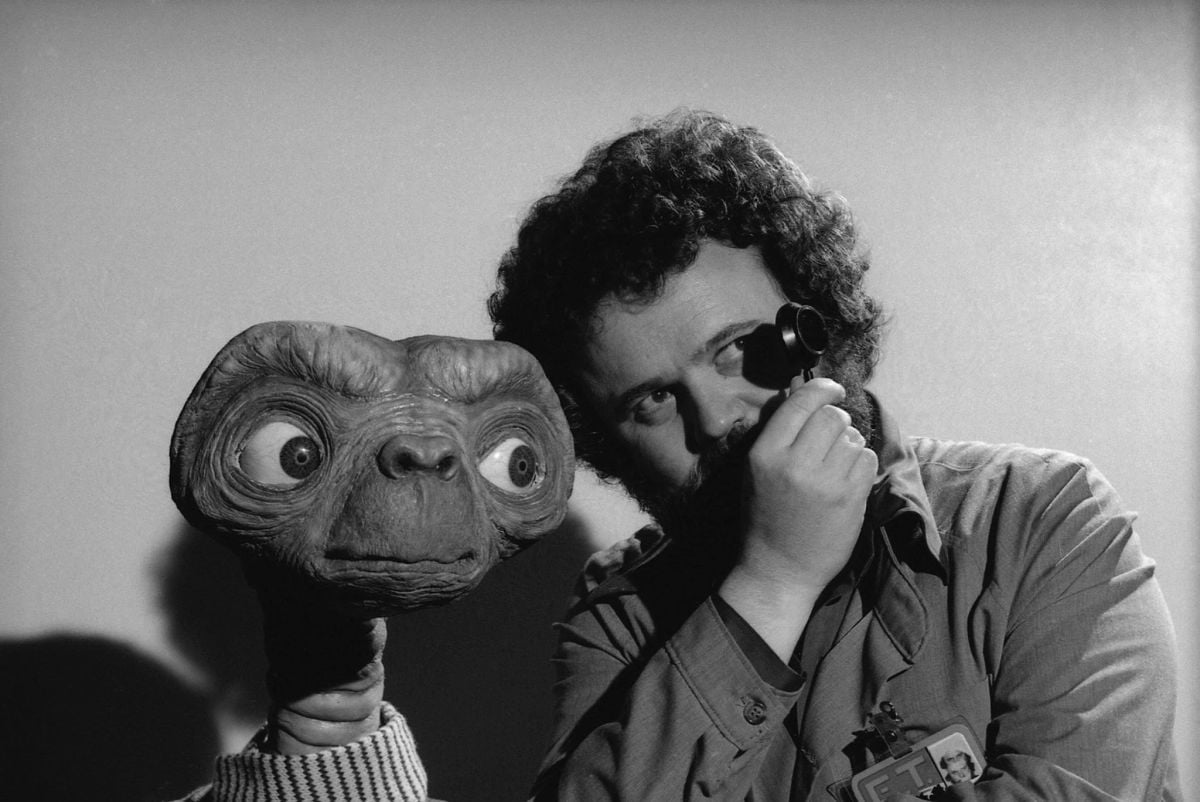

Allen Daviau, whose work as E.T.’s director of photography has brought him out of near-obscurity and into the spotlight, is as nearly a self-made success as can be found in Hollywood. He never attended film school but learned how cinematographers work by “gate-crashing” at various studios and watching his idols in action.

“I was a fanatic about movies and early TV,” Daviau recalls. “I watched the last days of ‘live’ television and marveled at the skill of the cameramen who were able to get so much variety out of a continuing performance. Then I watched Charles B. Lang [ASC] photograph some of One Eyed Jacks, and that was even more impressive. I still think Lang is one of the greatest cinematographers of all and I learned a great deal from watching him work.”

“Incidentally, nobody who knew Steven back in ’67 is in the least bit surprised at his success.”

Born in New Orleans during World War II, Daviau has spent most of his life in Los Angeles. While in high school he learned something about lighting equipment by handling the lighting on several stage plays. Unable to find any kind of job in the movie studios, he worked in camera stores and film labs, learning all he could about equipment and what it takes to put good images on film. In 1966, he bought a 16mm Beaulieu camera and launched himself as a freelance cameraman, shooting local television commercials and rock band promotional films for recording companies. Some of these were unusual enough to attract considerable attention. “Sometimes things get done because you’re too dumb to know they can’t be done,” Daviau says. He soon built a good reputation in the commercial field and was assigned as director of photography to many national commercials filmed in Hollywood, New York and Chicago.

“I still shoot a lot of commercials,” he says. “They’re the mainstay of keeping busy. You always have good equipment and crews, plenty of location work, lots of real interiors as well as studio sets, and an ever-changing variety of subject matter. I like anything that offers interesting lighting challenges.”

He also entered the documentary and educational film fields. Say Goodbye, which he helped photograph for David Wolper Productions, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary. His career received a big boost when he did several movie of the week features for television.

“Director Jerrold Freedman gave me my first break, [the TV movie] The Boy Who Drank Too Much,” Daviau recalls. “It was filmed on a 19-day schedule and I tried for as much theatrical quality as possible. I think any cinematographer should do that if he’s lucky enough to work with production people who will let you go after the ‘class’ look. When there are limitations of time and money, it’s best to get them to let you concentrate your best efforts on the scenes that will do the most good and do the rest more simply. I used the same approach on two other movie of the week entries, Streets of L.A., also directed by Jerry Freedman and starring Joanne Woodward, and Rage, directed by William Graham.

“One time he told me, ‘Allen, if you blow a scene because you went too far, I won’t be half as mad at you as I would be if you blew it because you played it too safe.’”

“Steven [Spielberg] saw some of my 16mm work back in 1967 and hired me to shoot Amblin’, a short subject that started us both up the ladder. He and I shared a great love of movies and tried to show it in this little film, which was my first in 35mm.

“Incidentally,” Daviau adds, “nobody who knew Steven back in ’67 is in the least bit surprised at his success.”

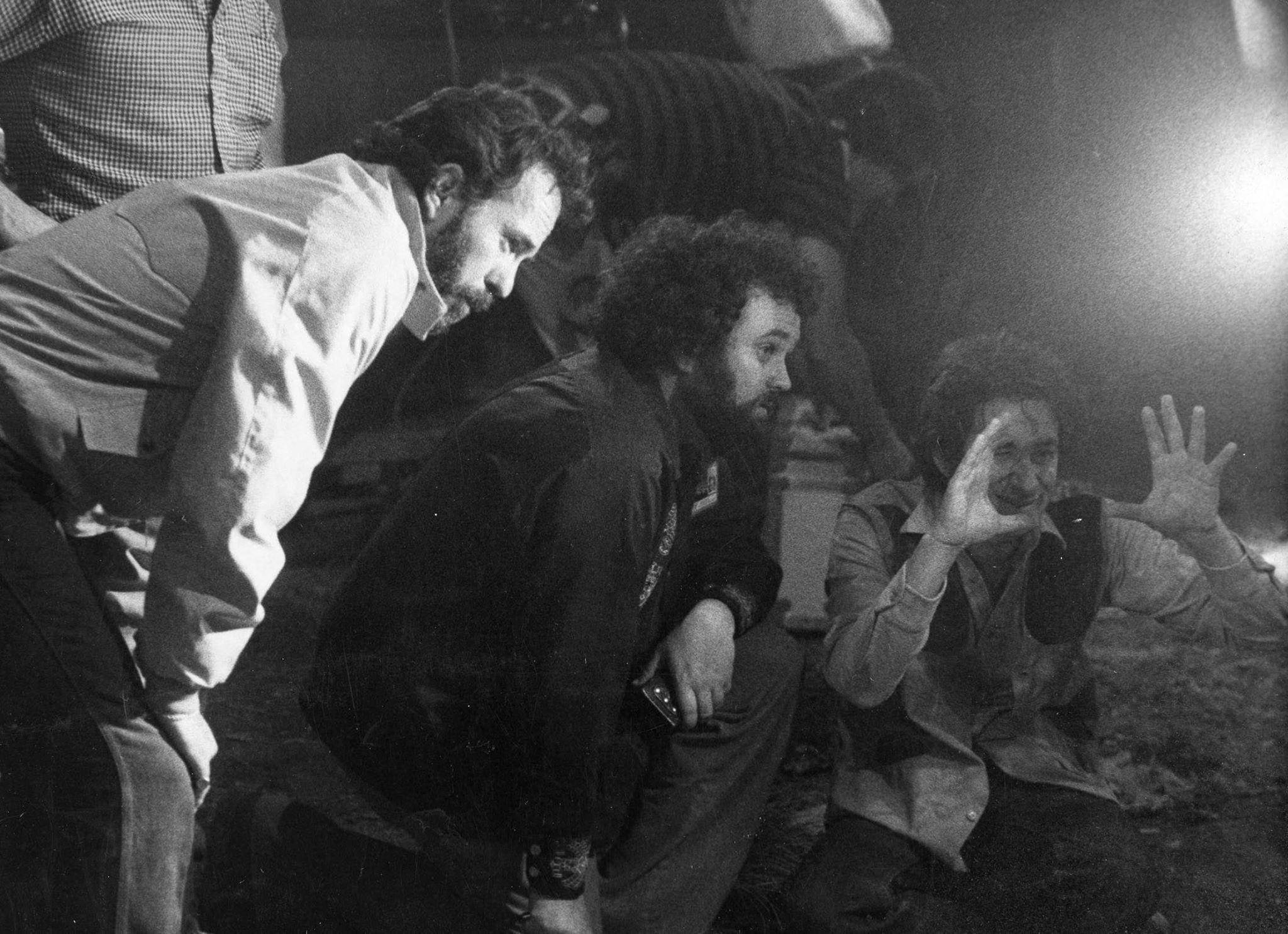

The next time Daviau worked with Spielberg was shortly after he received his IATSE designation. “It was the Gobi Desert sequence for the special edition of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Steven had seen The Boy Who Drank Too Much and called me. When anybody asks what it’s like working with Steven, I answer in two words: ‘never dull.’ He pushes you beyond what you thought you could do and brings out the best in you. He makes you look and think and never stop searching for something new. You will never get complacent on a Spielberg film.

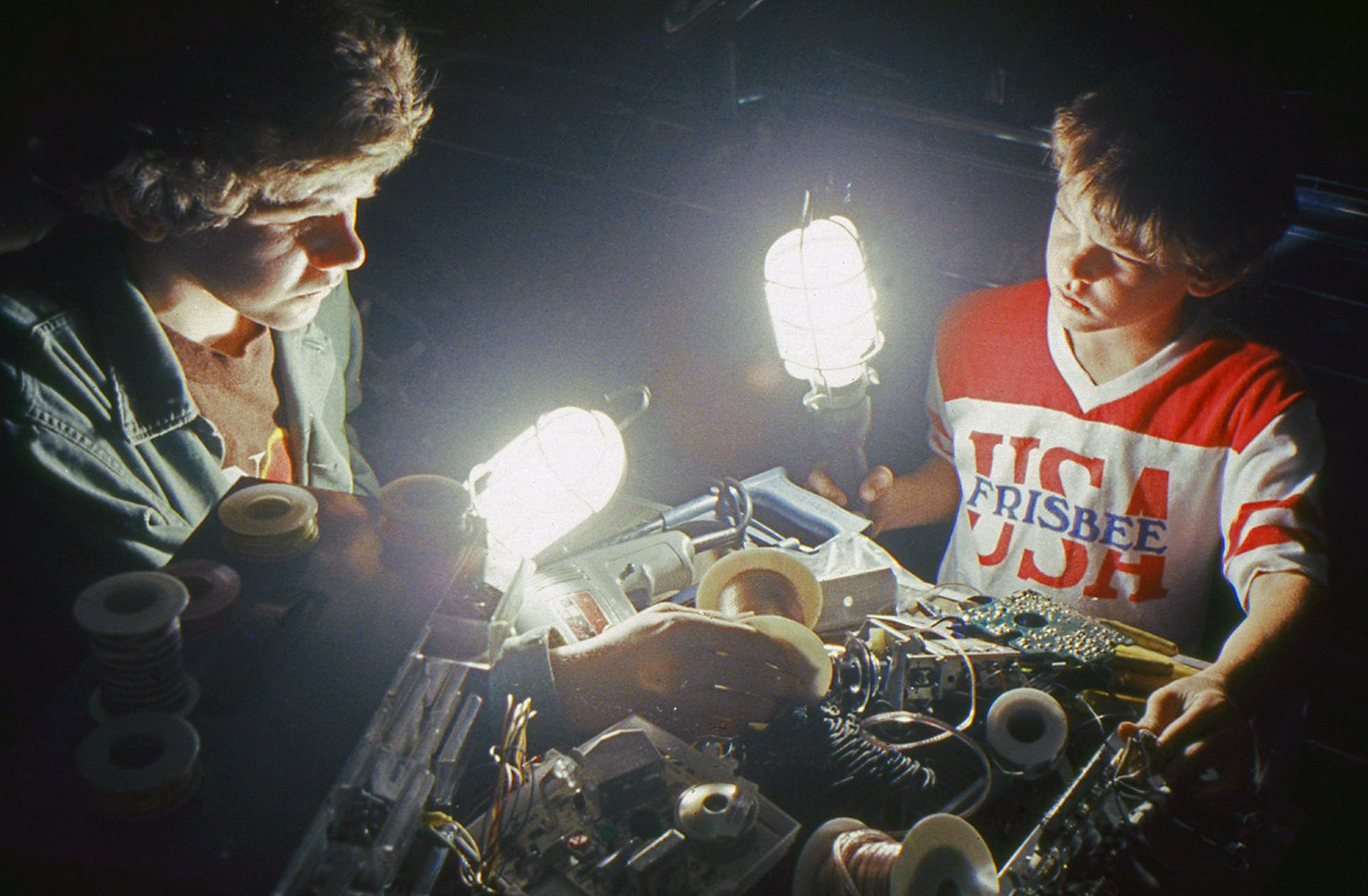

“One time he told me, ‘Allen, if you blow a scene because you went too far, I won’t be half as mad at you as I would be if you blew it because you played it too safe.’ For instance, one time he asked, ‘How would it look if we overexposed somebody’s face five stops?’ I wasn’t sure, but I gave it a try and held my breath throughout. It was when the boys were searching the garage for objects to build the communicator. The extreme contrast made a dramatic effect and the scene is in the picture.

“Steven will say two things that may appear contradictory. That means he wants you to work toward incorporating both. For example, he wanted E.T.’s skin to glisten but wanted him to stay indistinct. Another time he said, ‘I don’t want to see his face, but I want to see just enough.’ Challenges like that make for distinctive photography. For that scene in the bedroom where Elliott entices E.T. out of the closet, I had to make E.T. as near a silhouette as possible and still show his eyes!

“We first talked about E.T. in February of ’81. It was originally to start in May but it was postponed many times. Steven was finishing ADR on Raiders of the Lost Ark at Goldwyn Studio and I sat outside, reading the script. He said that if you’re going to do a modern fantasy in suburbia it has to have a basis in reality.

“It didn’t start shooting until September. One big advantage on this picture was to be on the job when the production designer, Jim Bissell, was planning the sets. Usually, the cinematographer is the last person hired and has to make do with whatever is handed him. This was the first time I was able to talk with the designer about, for example, where the windows would go.

“We sat down with Steven and started screening movies together. This is the best way I know to get started, watching our own movies and other people’s movies, discussing them, evolving the style we want. We watched Night of the Hunter, Alien, Apocalypse Now, Last Tango in Paris — I forget what all.

“Originally, it was to be storyboarded in detail, like all of his other pictures, but suddenly there wasn’t enough time. So only the special effects sequences were storyboarded. Otherwise, we were winging it. The house was as real as we could make it. The original house that was selected was in Northridge [California], but we wanted one that was backed up closer to the mountains. It was found in nearby Tujunga. We had to make it cut together with the neighborhood at Northridge.

“I told Jim that as much of the story takes place in the closet in Elliott’s room that it must have a window, otherwise how would the audience be able to tell day from night? And he figured out how to do it without it seeming strange that there should be a window — a stained glass window — in a closet! It’s just another example of how a first-rate production designer makes a cinematographer’s work more rewarding.”

Daviau also believes that much of the photographic success of E.T. is due to a first class lighting and camera crew.

“I first met my gaffer, Jim Plannette, and my key grip, Gene Kearney, on the set of Cannery Row at MGM. Jim introduced me to one of my heroes, Sven Nykvist [ASC], and I found myself unable to tell him how much his work has meant to me. The size of the set he was photographing was awesome and I was very impressed with the way Jim and Gene had rigged it to allow easy transitions from one time of day to another. This flexibility was carried over to E.T. With our schedule, day and night had to interchange with a minimum of delay, and with the help of their expert pre-planning and extensive improvisational abilities we were able to change time and mood almost as quickly as we changed our minds.

“One thing we borrowed from Sven was the use of muslin ceilings in the interior rooms. We were able to rig light from above that, when diffused by the muslin, added just the smallest touch of ambience to the day scenes without the look of ‘fill’ light.”

Interiors were staged at Laird International Studio in Culver City, which has a venerable history. Built originally in 1917 by producer Thomas H. Ince, it later became the Pathe Studio, Pathe-DeMille, and RKO Pathe. Such notable independent producers as Edward Small, Sol Lesser and David O. Selznick produced their best-known films there.

“I enjoyed working on the lot where King Kong and Gone With the Wind were filmed,” Daviau says. “In my mind there is a presence to a studio where great pictures have been made. I would at times have traded a small amount of that presence for a few more feet of grid height for the night backyard set on Stage 3, though. Poor John Fleckenstein, my operator, always had to just miss the low-hanging 10K above the garden. And on the widest of the wide shots we are seeing every inch of set that Jim Bissell had been able to fit in there. But, as they say, limitations can become strengths if you go with the flow. One of the perverse joys of cinematography is knowing that just outside of a perfectly framed scene lies total chaos.

“We used a lot of mist every day on that stage, which became known as ‘misty valley.’ Working with smoke and fog is an interesting experience. We were shooting in the late summer without refrigeration, and everything was okay in the morning while it was cool but as the day went on all the fog would roll toward the west wall, where the heat of the sun attracted it. We had to try to finish shooting before the fog started drifting.

“It’s very tricky, especially in big exteriors, to judge exposures in smoke or fog. I had to literally ‘light air.’ We had a few days of testing so we could play with the fog on stage. I found that averaging exposures using a spot meter was the best way. We did tests with a meter on a tripod and found there were no set methods or simple guides to exposure where you have to view elements in both the foreground and background. My advice is don’t try to jump around in the printing light trying to get exposures.

“It’s magic stuff. In the forest scenes, sometime the trees are only 20 feet away and the smoke gives the illusion of depth. Just look at the old Universal Sherlock Holmes mysteries; they were made on low budgets but they had real atmosphere and an effect of scope. They used ‘fog’ the way we did.

“I try never to become prejudiced in favor of only one kind of lighting. I always like to explore different ways of lighting. In this I got to use just about every technique of lighting I ever learned — hard-edged, old fashioned, visible source, tiny lights. We wanted the color clean, unfiltered, with good, solid blacks.

“Whether they like it or not, cinematographers had better get ready for electronic presentation of their work.”

“We used spherical format, with a 1:85 frame and 1:66 hard matte. We were working with a low light grid a lot, seldom no more wide open than T2.5, although we used the fast lenses. We used Eastman 5247 throughout with no pushing, no flashing — just the normal processing for natural, healthy negatives. We decided the texture should be sharp and clean with rich blacks.”

In the house interiors, Daviau used both soft light from practical lamps included in the decor and hard light as well. “The set decorator, Jackie Carr, and her assistant, Sandra Renfroe, brought in dozens of lamps and we auditioned lamps to choose the ones we wanted. We had to get fantasy colors and yet make them seem to come from natural sources.

“It was difficult figuring ways to keep E.T. working as something other than a mechanical thing. One way is having backlight behind him at all times with a lower light level in front so there is little detail in the face but with a catchlight in those wonderfully expressive eyes.”

One scene which helped to establish this style was, to the cinematographer’s sorrow, cut from the release version. “It’s near the first, when Elliott’s mother calls him upstairs. There’s an overhead light on, for the only time in the entire picture. As Elliott listens to the lecture, he turns off the overhead light, reducing his mother to a silhouette, and then he goes around turning on all the little lights he had placed around the room, relighting the place to his satisfaction. It was cut, dammit — but it was wonderful in that it established where all the lights came from that were used for all the scenes that followed in that room.”

When the field hospital was set up at the house the lighting effects were hard and the warm, homey atmosphere was gone. Yet the photographic technique remained consistent with the earlier scenes. “The field hospital sequence is a classic case of being able to have the light sources in the picture. Most of the lighting comes from real medical equipment. Steven likes the motif of lights shining right into the lenses. Remember Close Encounters? And we gave him plenty of that. We had great freedom to move around. My men, John Fleckenstein and [1st AC] Steven Shaw, were kept busy chasing people through those plastic tubes with the camera.

“The forest scenes are some of the toughest work in the film. You’d be amazed at how much cable it took for us to able to move around the forest at night. We had to be able to move the lights, find the boxes and not break our necks.”

Daviau doesn’t feel that a cinematographer’s job is done until the release prints are ready. “If a cinematographer is interested in what goes into the theaters he must follow the film through the lab. If it’s for TV he should oversee the electronic transfers. Whether they like it or not, cinematographers had better get ready for electronic presentation of their work.

“If I had to choose a favorite [scene], it would be the one in which the youngster [Henry Thomas] says, ‘I’m keeping him.’”

“For E.T., Deluxe did the first stage work and Technicolor made the release prints. We had no duped dissolves, it was all A and B work. The only dupes are in the actual optical effects work, as we wanted first-generation film whenever possible. The dailies were on 81 print stock, and by the time we got to the release prints we used 83 print stock. Steven said to keep it saturated, keep it strong and they did. Deadlines were fierce on E.T. but we had good rapport with both Deluxe and Technicolor for 10 weeks, and the color timer, Bob Raring, really knocked himself out for us.”

The consistency of photographic style is one of the remarkable things about E.T. Daviau says that much of the credit goes to the film editor, Carol Littleton, “who did a terrific job of keeping the style together.”

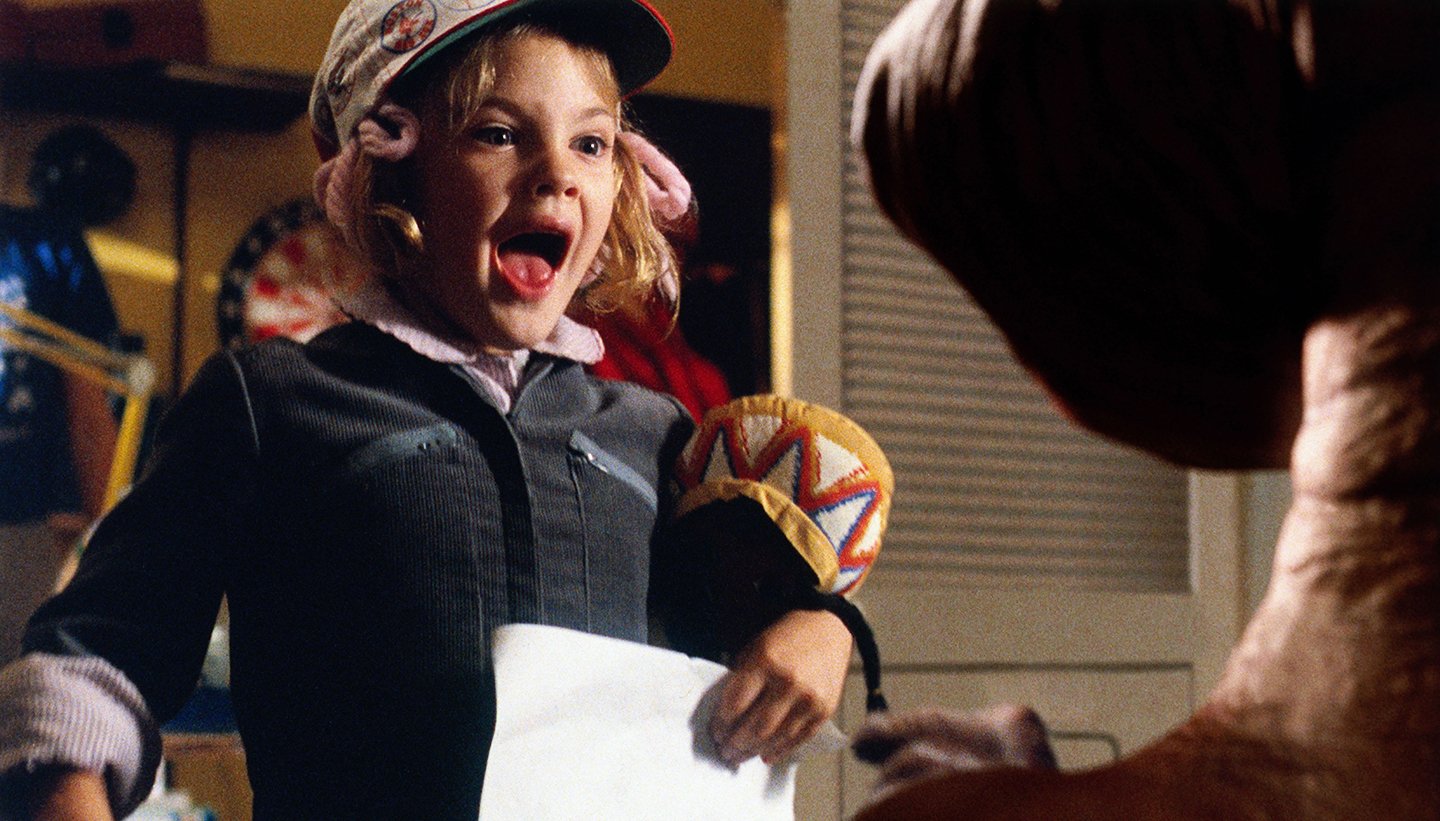

Every cinematographer has a favorite scene in each picture he works on, one that captures best what he wants to put on the screen. “If I had to choose a favorite,” Daviau says, “it would be the one in which the youngster [Henry Thomas] says, ‘I’m keeping him.’ The little girl [Drew Barrymore] walks forward, there are highlights in E.T.’s eyes, no detail in the face, and the light is yellow, the effect is very much that of a Maxfield Parrish painting.”

You'll find a companion story featuring director Steven Spielberg's take on making this classic film here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.