Star Trek 50 Part I — Original Series Effects

Three of the world’s foremost visual effects experts — ASC members Howard A. Anderson, Joe Westheimer and Linwood Dunn — discuss behind-the-scenes technology of creating illusions for imaginative TV space series.

The first entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise. This article originally ran in AC, October 1967. Some images are additional or alternate.

Out-of-This-World Special Effects for Star Trek

EDITOR’S NOTE: In a unique triple parlay of highly technical skills and talents, three of the world’s foremost studios of screen wizardry received a joint 1966 Emmy Award nomination in the Special Photographic Effects category in recognition of the spectacular illusions created for the Desilu-NBC outer space television series Star Trek. These studios are the Howard A. Anderson Company, Film Effects of Hollywood, Inc., and the Westheimer Co., all of which, headed by top ASC Special Effects experts, worked separately but in a spirit of cordial collaboration to produce some of the most stunning and literally “far out” visual effects ever to be recorded on color film. At the request of American Cinematographer, the Presidents of the respective companies involved kindly consented to explain the technology involved in creating several of the aforementioned effects, and their individual comments follow.

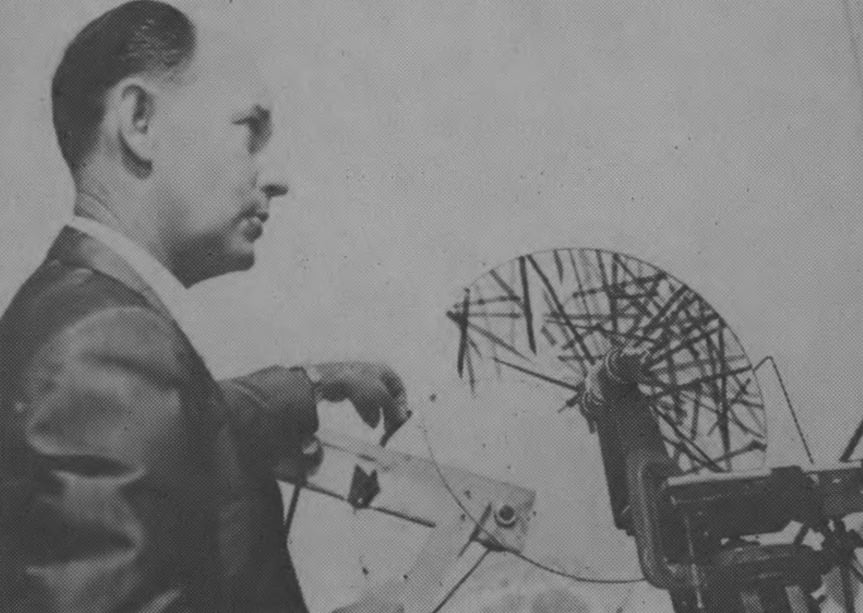

HOWARD A. ANDERSON, ASC

President, Howard A. Anderson Co.

Our contributions to the photographic special effects for Star Trek, which were responsible for our receiving an Emmy nomination, fall into three principal areas:

(1.) The design and building of the miniatures of the spaceship, the U.S.S. Enterprise.

(2.) The creation of the effect of traveling through space at speeds beyond comprehension.

(3.) The de-materialization and re-materialization effects in the transport chamber of the Enterprise.

This work, which required the creative talents and experience of 20 of our technicians, was conducted under the direction of Darrell Anderson.

Our work on Star Trek began a full year before the first pilot (there were two pilots) was made. [Executive producer and series creator] Gene Roddenberry outlined the concept of the series for us and asked us, aided by the Star Trek art director, Matt Jeffries, to design a model of the Enterprise.

One of our most difficult assignments for the series was to create the impression that the Enterprise was racing through space at an incredible — faster than the speed of light, which is 6,000,000,000,000 miles a year.

Other space shows have shown spacecraft more or less “drifting” through space. We wanted to avoid that cliché. The solution did not come easily or quickly. We experimented with dozens of ideas before we hit on an effective solution.

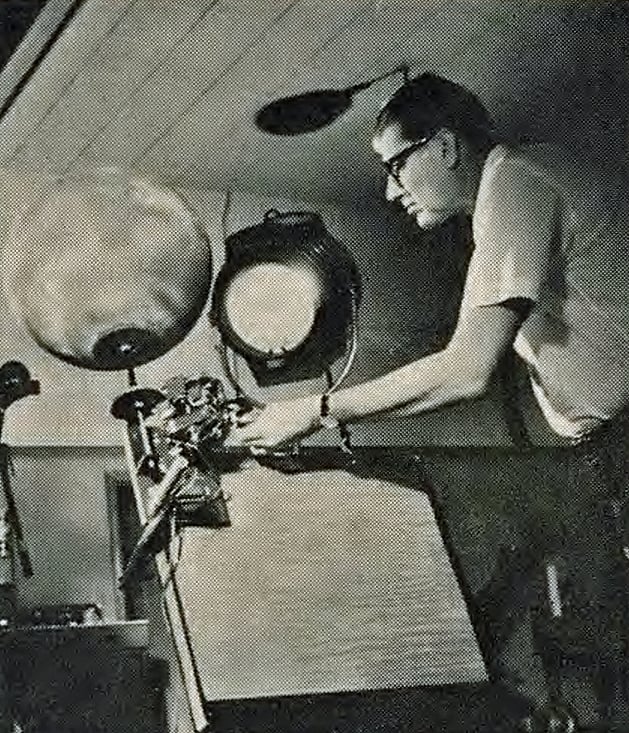

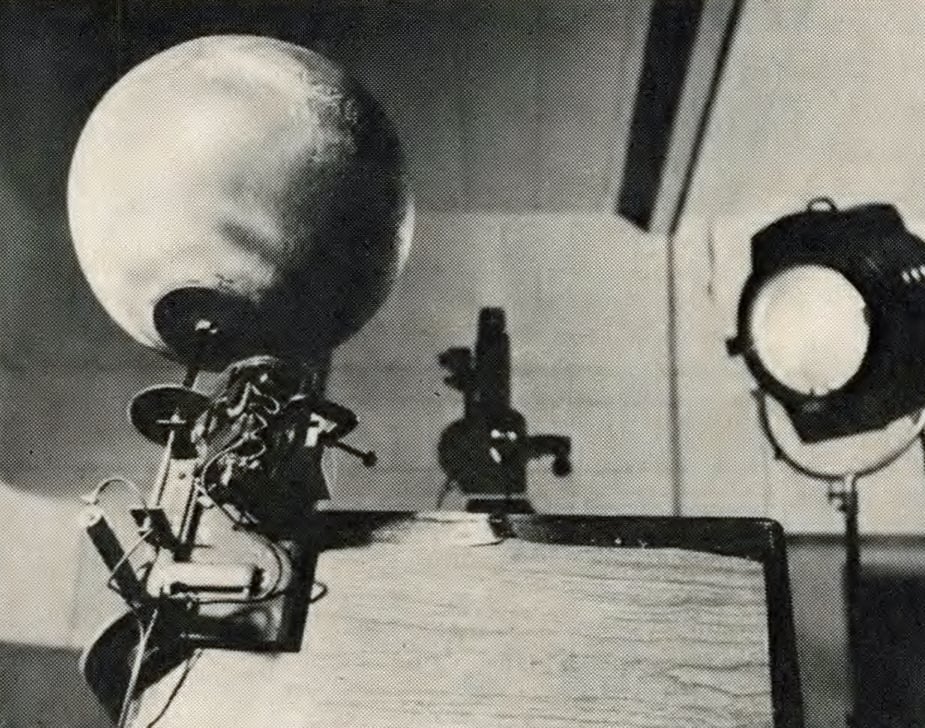

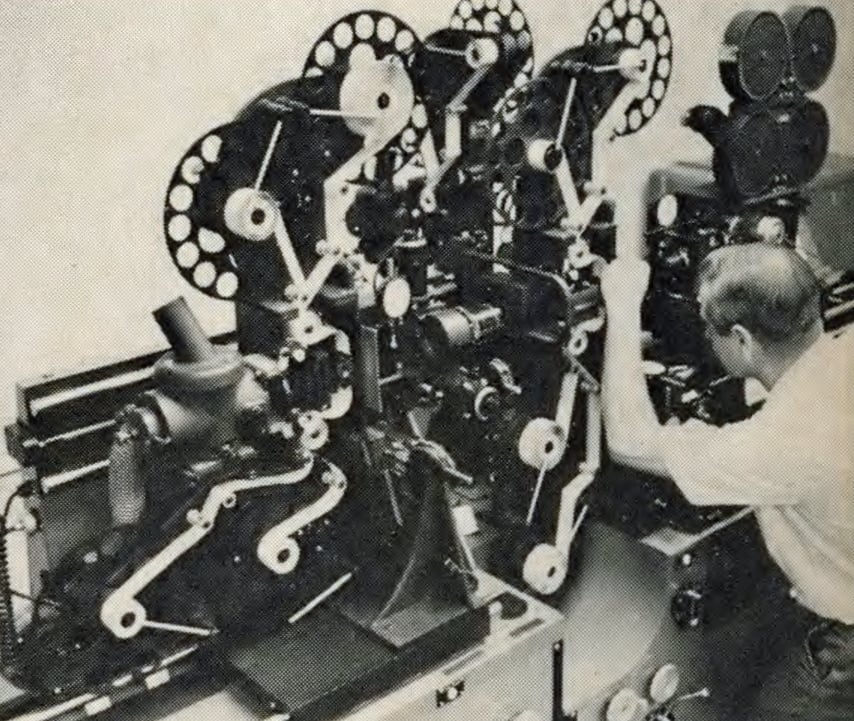

The principal elements in our solution are a space sky and the use of an Oxberry optical printer. To make the space sky, we painted black stars on a white background about 2 ½ feet by 3 feet, arriving at a suitable design. We then made a series of black-out mattes that we could use later with the sky in the optical printer.

The advanced Oxberry printer was unique at the time. It is capable of making a 5-to-1 reduction through a 4-to-1 enlargement with continued automatic focusing. The space sky was photographed and a still frame used on the optical printer. We tracked the space sky to the left, to the right, to the top and to the bottom, using a different black-out matte on each pass and superimposed these various moves at different speeds. We were able to create the illusion that the Enterprise was racing through space at an incredible speed. We start with a space sky filled with some 500 stars and finish with perhaps 30 on each pass. In the automatic focusing process, we got from a 3-foot scope down to about 10 inches.

The spaceship, as imagined by the producer, was larger than a battleship, had eight separate levels, or decks, and carried a crew of over 400.

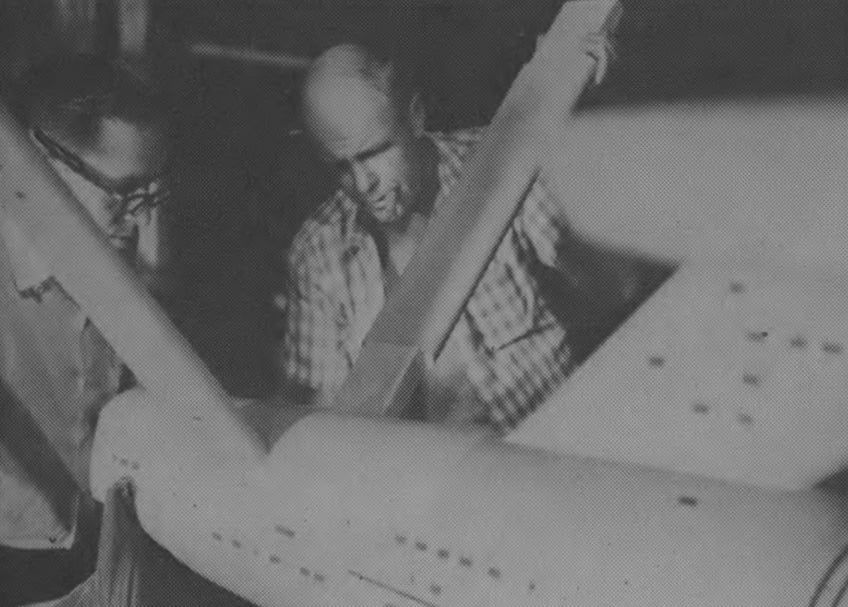

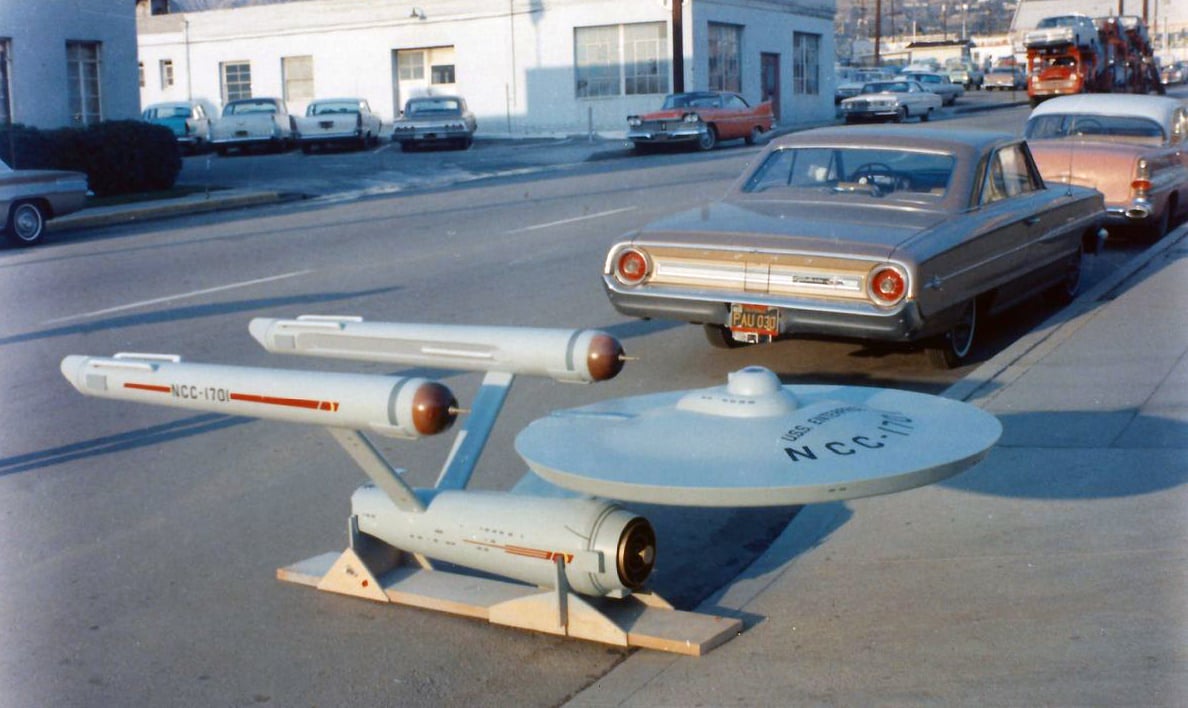

The first step was a series of art renderings by Jeffries. When Roddenberry approved his final design, we moved to the next step: translating the rendering into a 4-inch scale model, constructed of wood.

Our next step was the construction of a 3' model, which again was constructed of solid wood. This model, of course, had far more detail than the first. Once it had been approved by Roddenberry, we were ready to proceed with the large, detailed model.

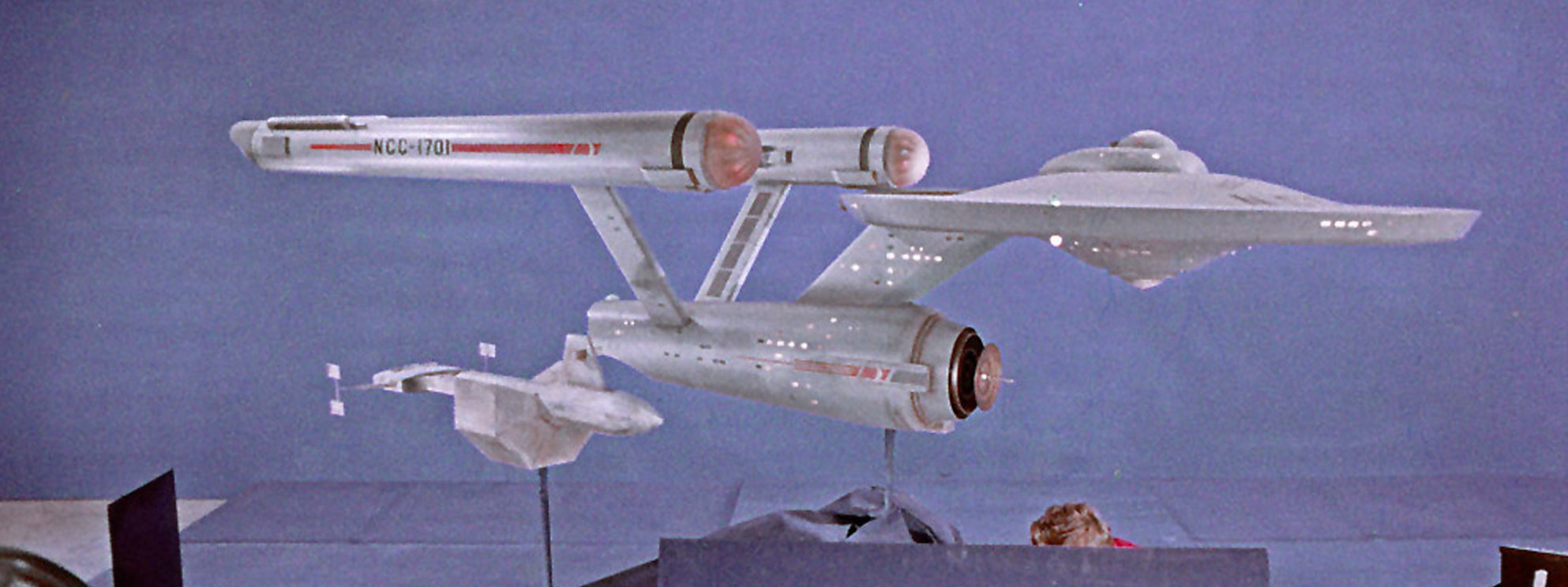

This was an elaborate 14' model, which was made mostly of sheet plastic and required hundreds of man-hours of work. The diameter of the dome — or main body — of the ship was 10 feet. The pods were hand-tooled from hardwood.

After the first pilot was made, two major changes were made in the design of the Enterprise for the second pilot. First, at Roddenberry’s suggestion, we built a landing deck on the rear of the spaceship. And, second, at our suggestion, he approved a complex electrical system for interior lighting. This, we felt, would convey the feeling of life and activity aboard the spaceship. And it also helped to create a more vivid illusion of the enormous size of the craft.

The process proved to be extremely effective. It gave a feeling of passing through the stars and planets and not merely passing by them.

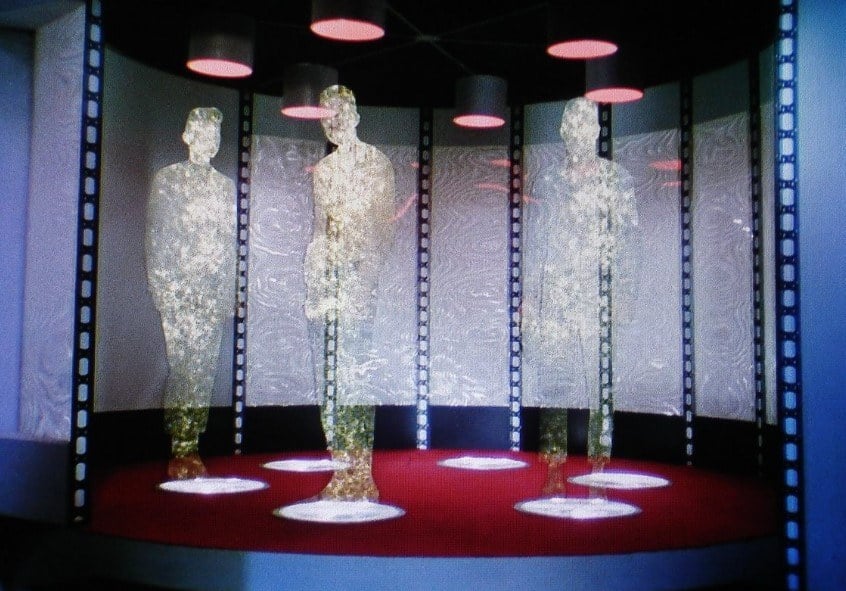

The third major effect we created for the series was the de-materialization and re-materialization in the transport chamber. This is the room in the Enterprise from which or to which the crew of the spacecraft and other life forms are sent to or brought from other spacecraft or planets.

A simple answer would have been the standard use of mattes and dissolves. We decided to try to develop something fresh and distinctive and were successful.

Normally, the effect would be accomplished in the following steps:

- The person (or persons) to be “transported” is filmed in the transporter set.

- The camera freezes, the person steps out of the scene, and the camera films the empty set.

- From a dupe negative, a matte is made of the figure at the freeze point.

- The figure is then dissolved out, leaving the empty set.

But for the transporter effect, we added another element: a glitter effect in the de-materialization and re-materialization. To obtain the glitter effect, we used aluminum dust falling through a beam of high intensity light. This was photographed on one of our stages at our Fairfax Ave. plant.

In addition to making a matte of the figure to be transported, we also make an identically shaped matte of the falling particles of aluminum.

Then, using the two mattes, we slowly dissolve the person, leaving only the glitter effect, then slowly dissolve the glitter effect to leave nothing but the empty chamber.

The three areas discussed by no means represent the full extent of efforts for Star Trek. But each constituted a distinct and unique challenge to our creative ability. And each brought us a great satisfaction in fulfillment of that challenge.

LINWOOD G. DUNN, ASC

President, Film Effects of Hollywood, Inc.

Special photographic effects created by Film Effects of Hollywood for the Desilu-NBC Star Trek series include many creative optical printing techniques combining a variety of unique original film elements. This work includes distortion of contrasts and color values of normal scenes, mysterious planets and images streaking through space, comets with varicolored tails, fire balls, “phaser” beams, and a great assortment of out-of-this world effects and strange transformations. Churning, weaving forms and masses hanging in space, as seen through the U.S.S. Enterprise’s viewing screen, were created by photographing the action of special dyes fed into a tank of clear liquid. With a certain measure of control over the action of the dyes, fascinating and often unexpected varieties of weird, shapeless forms and colors evolved.

In some instances relatively simple devices were utilized for shock effects, such as a sword passing through a figure, the appearance and disappearance of objects, overall color and diffusion manipulations, etc. An intriguing time roll-back device was created when our space travelers stepped through a wall of smoke emanating from the inside of a rock-like frame which glowed in modulation to the voice of a “master spirit.” Inside this frame, time was rolled back before the eyes as scenes from the past streaked by, pausing momentarily at significant eras.

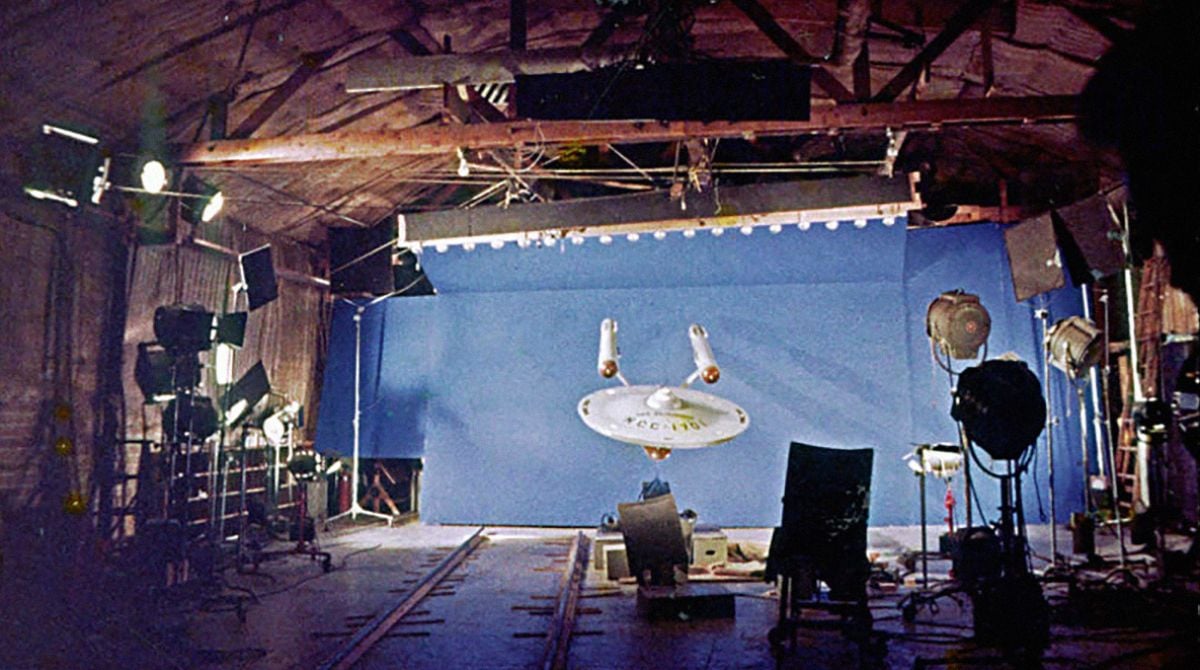

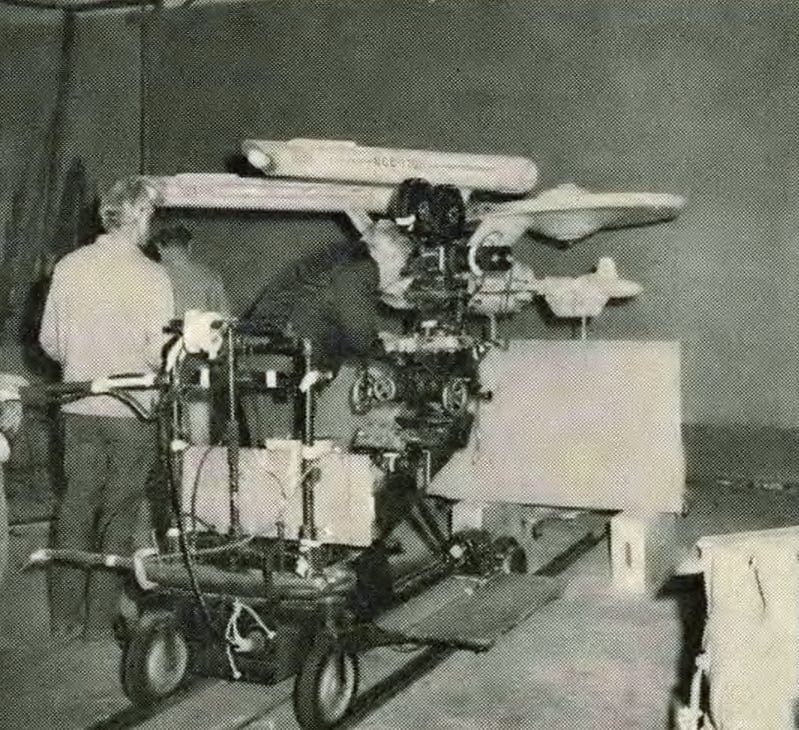

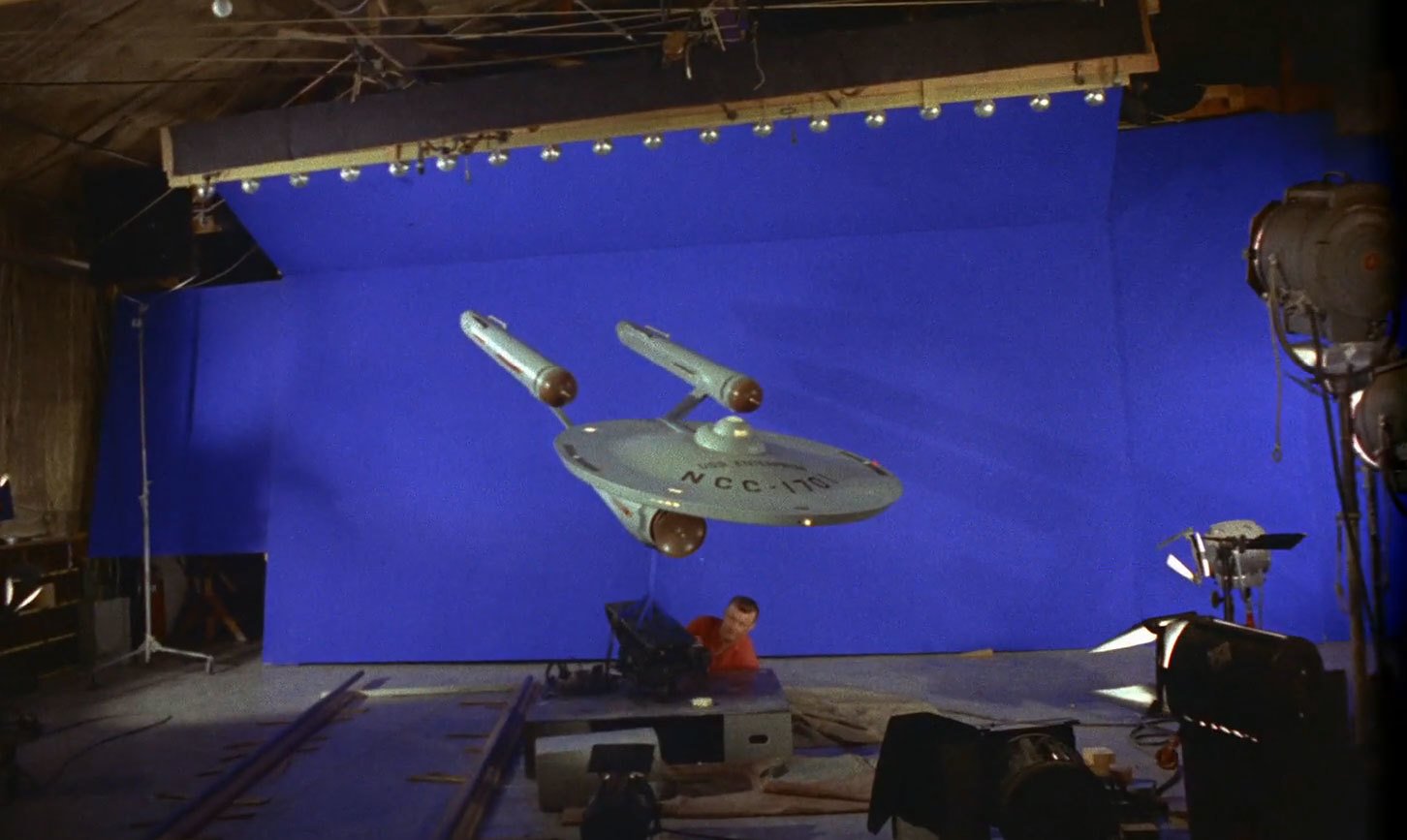

Film Effects was given the assignment to carry on with the fine work started by The Anderson Company, in the photography of the space ship U.S.S. Enterprise. Three-foot and 12-foot models were used, the latter fully equipped with interior and exterior lights, and twin motors emitting flashing multi-colored light effects, spinning on the noses of the engine nacelles. Most of the apparent motion of the ship was produced by the camera’s travel forward and back. All motions were motorized — the dolly travel, the camera boom raising or lowering, the tripod head panning or tilting, and the lens zooming forward or back. In addition, the Enterprise, mounted on a shaft attached to a tilting and panning tripod head could execute certain remotely controlled motions which, when combined with the camera’s actions, could carry out practically any type of maneuver. The use of an 18mm lens made it possible to accentuate the speed of travel as well as retain an adequate depth of field.

Certain elaborate shots were required, such as combining the actions of the Enterprise with those of other ships, as when the Enterprise overtakes a smaller ship and jockeys into position to “lock on” by means of a magnetic force. A larger-scale model of the Enterprise flight deck was built, from which its small “shuttlecraft” takes off and returns, the rear clam-shell doors sliding open and closed. The craft’s movement forward and back, and to and from the revolving platform on the deck, was maneuvered by wires which also controlled the craft as it soared into “space,” suspended from a special rigging mounted high outside and above the flight deck.

In all cases where the backgrounds were to be star fields the blue-screen traveling matte process was used in the standard manner. Some problems were encountered in matching the pedestal and tripod head on which the Enterprise was mounted, to the blue background screen. A very important step in the compositing of foreground scenes with the star fields was the matting out of all but the bluescreen areas. This was particularly difficult when the camera dolly made fast moves, as it became a frame-by-frame or foot-by-foot hand matting procedure, executed on the rotoscope crane. There, the scene was projected on the animation platen, and mattes were painted, blocking out the unwanted areas, to produce supplementary mattes for use with the photographic mattes created by the reaction of the blue background to the special separation filters.

The background star fields were created by punching holes of various sizes, in proper scale and location, in large sheets of black paper, backed up by special diffusion screens and color filters to create the desired effect. By combining scenes made at varying camera distances and travel speeds, a realistic illusion of depth was created. This was particularly important in star fields which tied-in with forward or reverse travel of the ship, and seen on its forward viewing screen.

Tremendous imagination is evident in the scripts produced by producer Gene Roddenberry and his staff. As the unique Star Trek format is conducive to free creativity, there were obviously times when certain effects were found to be difficult to produce within the budget and time limitations allowed. Modifications, incorporated as the work progressed, often resulted in very acceptable substitutions. Flexibility of this sort is primarily a matter of understanding and cooperation between all parties concerned, and is the kind of relationship that we enjoyed with the production staff of Star Trek.

JOSEPH WESTHEIMER, ASC

President, Westheimer Company

The special photographic effects on the Star Trek show fall into five major categories.

First are the shots of the U.S.S. Enterprise flying in space or orbiting a planet. The planet varies in color from show to show so either the color of existing planets are altered or new ones shot to meet the requirements of the producer. In addition to color changes they may be shifted to different parts of the scene, turned over or even used upside down.

The second type of effect is materialization of the people as they are transported to the ship from a planet or to the planet from the ship. The U.S.S. Enterprise is a space ship, official designation “Star Ship Class” and is somewhat larger than a present-day naval cruiser. There are various Transporter Rooms throughout the vessel. In a Transporter Room there is a console controlled by the transportation officer and a technician. They, in concert or singly, can transport up to six people at a time and of course return them. At times objects out in space which are close to the ship can be brought aboard.

The transporter itself is essentially a device which brings crew or cargo to and from planet surfaces and/or other space vessels. It converts material temporarily into energy, places that energy into a fixed place, then reconverts it back into the original material structure. The materialization or transporter effect is accomplished by superimposing a glitter over the form of the people or object which is being transported.

The third, phaser effect, can be divided into two classes. The “hand phaser,” which is hardly much larger than a king-size package of cigarettes, and the “phaser pistol,” which consists of the hand phaser snapped into a pistol-grip mount; the handle of which is a power pack. This greatly increases the range and power of the weapon. Both the hand phaser and phaser pistol have a variety of settings and adjustments. Most often used is the stun effect which can knock a man down and render him unconscious without harming him. Full effect, which causes an object to dematerialize and disappear, is another. The phaser is also capable of being set to cause an object to explode or put a hole through an object similar to a cutting torch. Visually the phaser is a pulsating beam which varies in color depending upon whether “stun effect” or “full effect” is desired. The full beam is animated across the screen and varies in width as well as density.

The fourth type of effect is the television reductions and superimposures. Aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise are many viewing screens. The most important is the Bridge Viewing Screen. It is an elaborate device which can be pointed outside in any direction and with various magnifications. Most often it is pointed straight ahead and we see stars pass as well as approaching planets and asteroids. Other television screens are used throughout the vessel as intercoms. There is also a rectangular screen in the library computer station on which can be flashed visual information from the ship’s recoding tapes. When these effects are required, mattes are made for the screens and scenes are reduced optically into the screen area.

Fifth and finally are the scenes or sequences in which an optical effect is created literally from scratch. These effects can be classified as “esoteric adventures.” The producer will, for example, have a sequence in which the ship is approaching a glowing sun at high speeds. A slow zoom shot of the sun is required, growing from pin point size to almost filling the screen, at which time the ship will veer away to avoid collision. Another request might involve a chase between the Enterprise and an alien ship which zig-zags away from its course as our ship follows in pursuit much like a World War I dog fight.

A recent request, to quote the script, was for a “columnar-like area of blurry, misty interference of some sort. It is rather like a gentle whirlwind, but one of force rather than air current. Faint pastel lights and shades appear and disappear. It moves from side to side gently and then disappears.”

From this description our optical company must create on film the effect that the writer has conceived. After the production meeting and further discussions with the director, ground rules are laid out so the production scenes are shot in such a way that they can be composited optically.

Conferences are held with the executive producer, the producer and associate producer. Tests are made of the “pastel lights and shade” and overall shape.

Finally, a shot is composited as a test. Suggestions for improving the effect are offered and the shot is composited.

In some way with uncommon persistence, the producers obtain optical results comparable to the high quality of the production itself. It is the technical awareness and competence of all members of the Star Trek production and editorial staff which enables communication with the optical house to be on a high professional level.

The show itself is challenging, intelligently produced and well written. To be associated with a production of this caliber is itself an honor.

The original 11' Enterprise NCC-1701 studio model was received by the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum from Paramount Studios on March 1, 1974. It was restored in coordination with original prop designer Matt Jeffries and series creator Gene Roddenberry and put on public display. Additional restorations were done in 1984 and 1991. On June 22, 1999, the model underwent X-Ray analysis at QC Laboratories, Inc., in Aberdeen, Maryland. It was completely overhauled in 2014-’16, with model totally restored, and remains on display today.

Missing since 1978, the original 3' Enterprise model was rediscovered in 2024 after being placed on a public auction site. It was then acquired by Roddenberry Entertainment.