Star Trek 50 — Part II Shooting The Motion Picture

The cinematographer on the film’s photographic challenges on a cosmic scale, including the lighting of an alien entity located somewhere east of the sun and west of the moon.

The second entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Trek franchise.

In a sense, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a victim of not enough time in preparation.

Unfortunately, in the production of all science-fiction films, there never seems to be enough time — so we were not unique in that respect. Up until the filming of the very last sequence, planning had to be done on a day-to-day basis.

One of the major problems was the fact that Doug Trumbull and his special effects team did not enter the scene until deep into the filming of the principal action. Unfortunately he was not around during the pre-planning stages — which would have made it much easier for us to forge ahead. As it was, Robert Wise, Harold Michelson (the production designer) and I, along with a production sketch artist and several other talented concept individuals had to constantly put our heads together and try to plan ahead. There was hardly a day that we didn’t meet during lunch to discuss what we were going to be doing after lunch. It always seemed to be “right up to air time.”

That is the sort of pressure we were under in trying to get the project completed properly and on time, in trying to shoot the most sophisticated of all science-fiction films without sufficient pre-planning. Our main problems stemmed from not having Doug Trumbull and company aboard earlier, plus the fact that the story was being written as we went along — which made it most difficult to plan ahead.

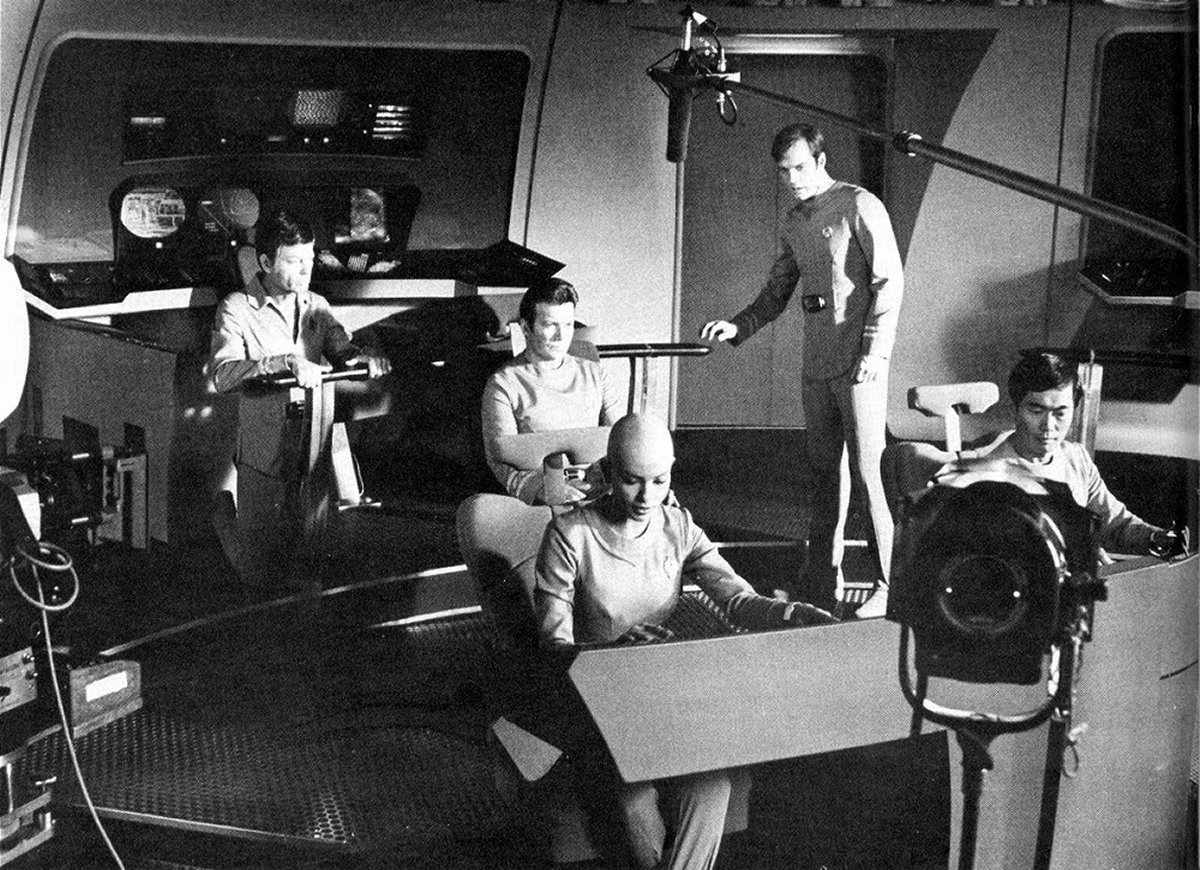

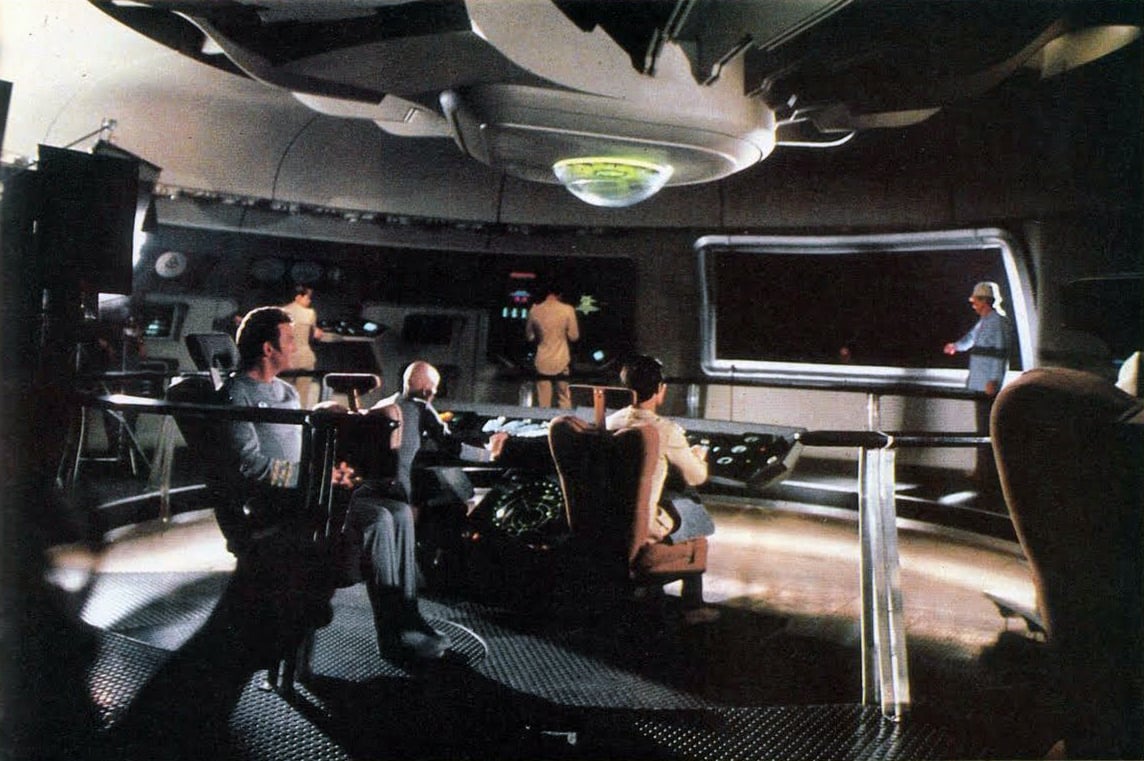

I would say that roughly three-fifths of the action of the film takes place on the bridge of the Enterprise, where a lot of effects occur (the majority of them being postproduction effects). We endeavored to at least make it easy for the effects people by making sure that what we were shooting on the Bridge would relate in both texture and color values to the postproduction effects that hadn’t been created yet. That’s where Bob Wise, Harold Michelson, the sketch artist and myself had our heads together all the time.

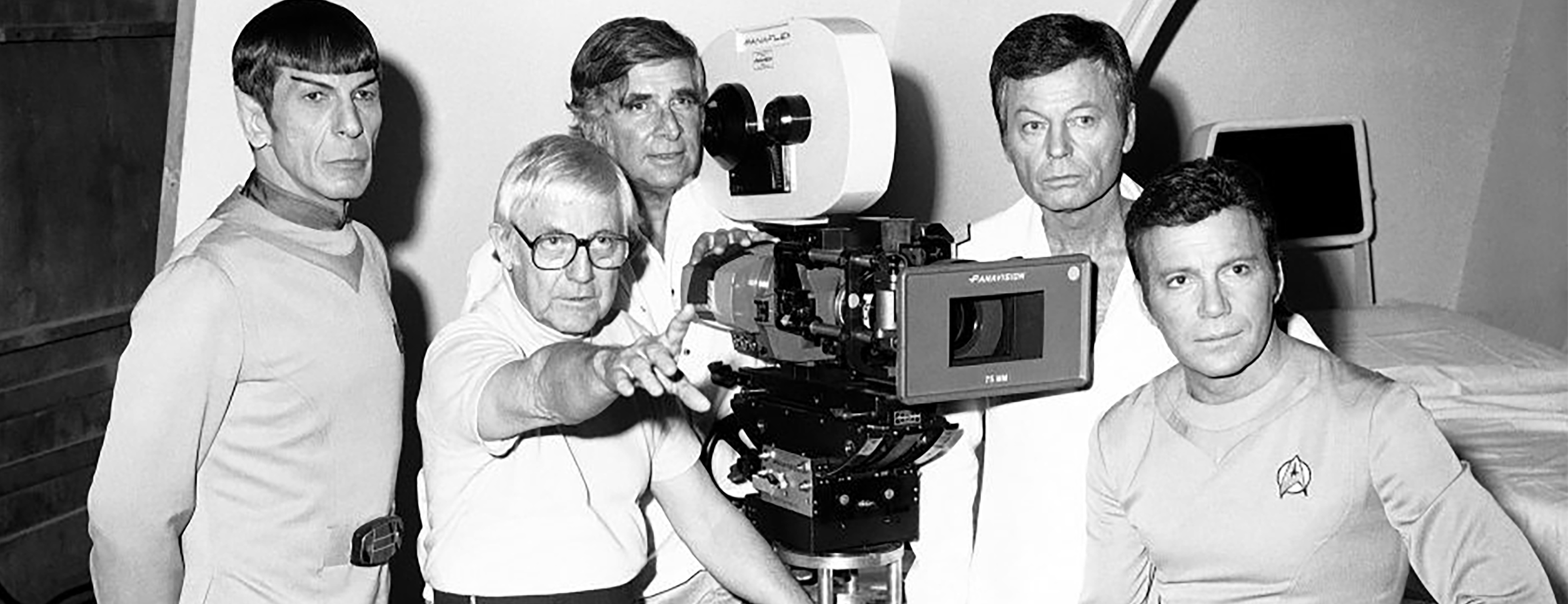

Diverging from technical details a bit, I must say that the members of the cast were delightful to work with. Almost all of them were veterans of the original TV series, which had not been produced for a decade, but it was as if they had been put into cryogenic deep freeze and brought back to life for this feature. They looked marvelous, their attitudes were brilliant and they were very well-coordinated in their playing.

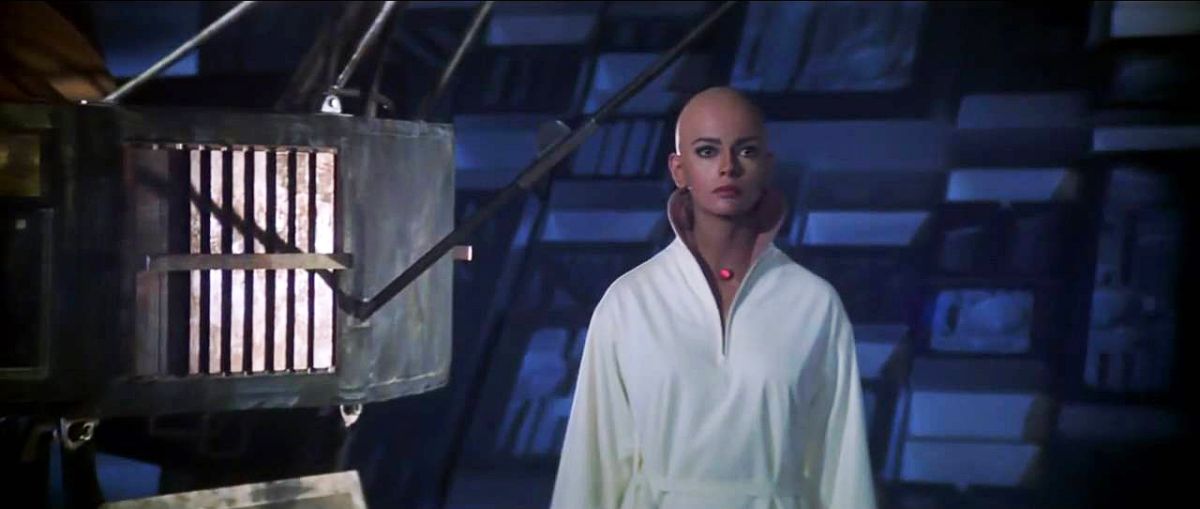

One of the two new major cast members was Persis Khambatta, a very striking woman who had to shave her head completely to play the role. That might sound easy enough, but I must say that it was rather difficult to retain a visual continuity because, just like a man with his beard, she would develop a “five o’clock shadow” on her head. Also, as a result of the constant shaving of her head day after day, she would develop a rash and a very clever type of makeup had to be applied constantly in order to hide it.

I must say that she was extremely cooperative, especially in view of the fact that there was another annoying element that she had to live with. It was a prop — a small red light that she had to wear around her throat. In terms of story point, it was supposed to be a sensor light, a direct feed to whatever was controlling her. At any rate, it was about twice the size of a nickel and twice as thick and we would have to stick it onto her throat in the cavity above the chest and then run two wires around to her back, where there was a battery. I must say that the poor girl was taped and untaped more times than a Rams linebacker is before and after games during his entire career. But again, she was extremely cooperative, and would stand for hours while we applied these various devices to her. From the photographic standpoint, concealment of the wires was a constant problem and the battery on her back was very difficult to light around.

Meanwhile, back on the bridge, it was very difficult to get camera movement into the photography, mainly because the set was on several tiers. This meant that every time someone wanted to move the camera the dolly track had to be elevated and shored up, or there would be some sort of obstacle in the way of what otherwise would have been an easily accessible dolly movement or camera position. The fact that the principal command seats (for Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock) were locked in position and couldn’t be shifted gave us some problems.

One of the challenges we had to cope with from the start was the fact that the bridge was surrounded by computer readouts that were rear-projected, for the most part (although others were put in by means of blue screen). In order to make these rear-projections read on the screen, the general lighting level had to be kept very low. I was working at approximately 20 footcandles throughout the filming of the entire picture. Now, one of Robert Wise’s requests — and one which I agreed with — was for a rich depth of field, which is quite difficult to achieve when you are working in the anamorphic format at very low light levels. To solve that problem I used split-diopters on, I would say, 80 percent of the scenes — sometimes as many as three. I feel that these did an excellent job for us and we were able to slide them on and off as we panned the camera; we weren’t confined to stationary shots. The main consideration was always to hide the blend line with a shadow, a hot spot or a vertical line in the set.

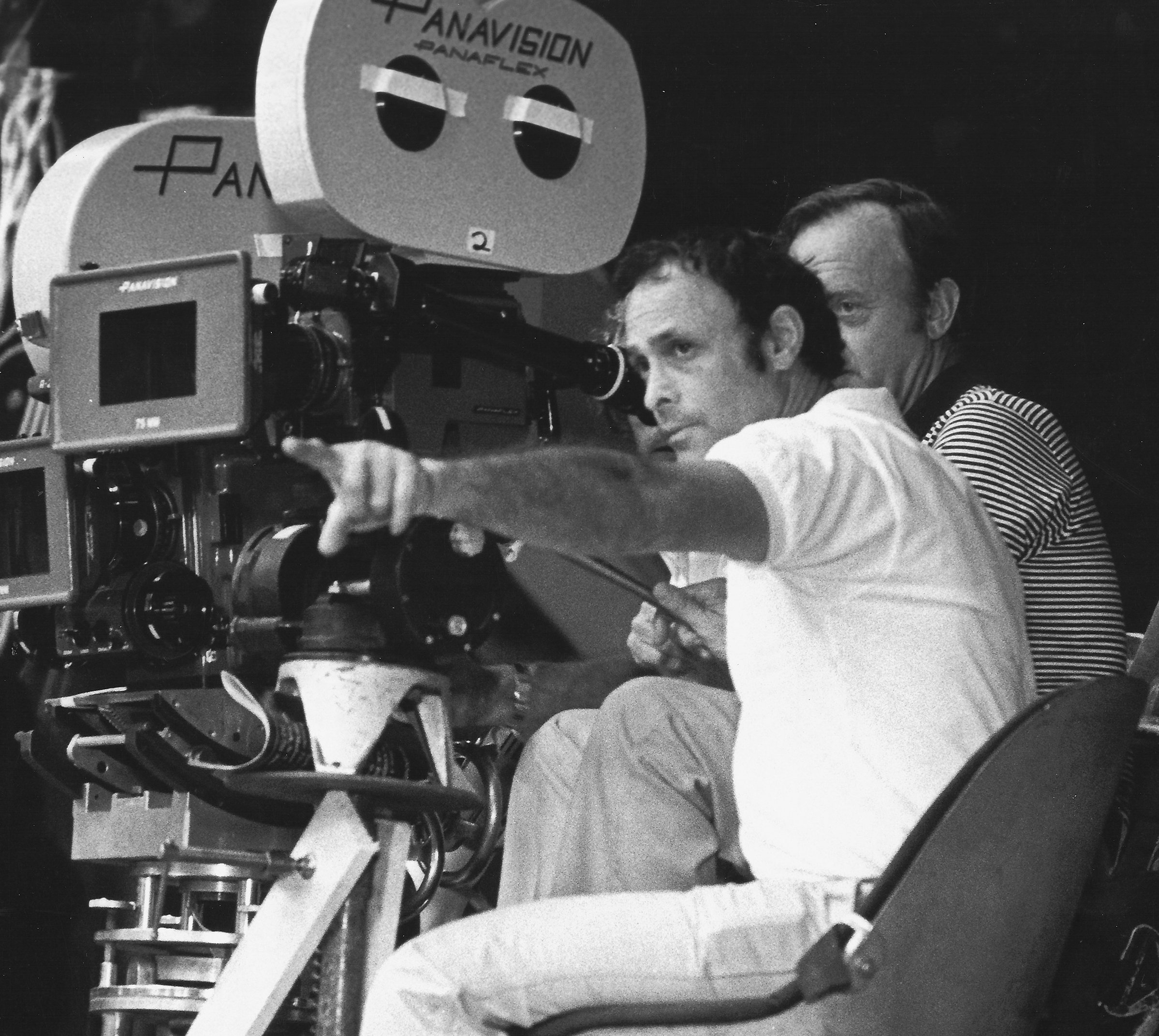

The style of the sets, as designed by Bob Wise and Harold Michelson, was to be very sterile and we were always careful to have everything spotless. It had a pristine look to it. So the visual style added up to a combination of this sterile look, very soft (not harsh) colors and great depth of field achieved through the use of split-diopters (of which Panavision’s are, without a doubt, the best). The availability of the Panaflex camera also enabled us to get into tight corners where a conventional camera would never fit.

With all of these elements working together, I do think we have a striking-looking film. It is very stark and the characters are very bold visually. They are unique-looking. The wardrobe was very carefully designed and every detail was approved by Bob Wise. He is very thorough and probably the most “complete” director I’ve ever worked with. This marked the second occasion that I’ve worked with him (the first was The Andromeda Strain) and I must say that without Bob Wise I don’t know where this picture would have been. I don’t know how we would have achieved what we did. His thorough knowledge of every aspect of production and his unrelenting determination to get what he wanted onto film were always in evidence. He would not give up on anything. He would try, try, try something else.

The major illumination in the sets was basically a lot of bounce light, but in order to avoid the monotonous look of flat, soft light, I used it in a contrasty manner — soft light, but projected from side angles. I also used quite a bit of straight backlight. For example, I would light a wall and let an actor go semi-silhouette or full-silhouette against that wall.

Unfortunately, we were limited by a set that was not a breakaway set. Everything was practical. There were ceilings and there was really very little chance to conceal lights. In addition, with the myriad of monitors that had reflective glass in front, you couldn’t hide light where you wanted to because the glass was always picking up reflections. So I did use soft light, many times bouncing it off of cards or Foamcore. Sometimes, as I have said, it was quite contrasty; at other times I used the same kind of light, but in a very low-key way.

What I tried to do was avoid the monotony of one type of lighting. In this respect, some color values were used to add another dimension, and there is a variety of textures throughout the entire film. These helped to get away from any sameness in the use of soft light.

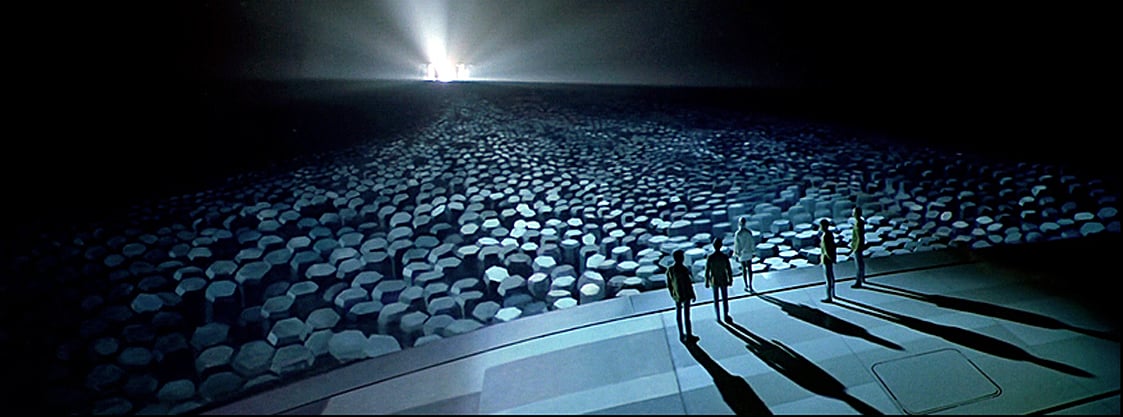

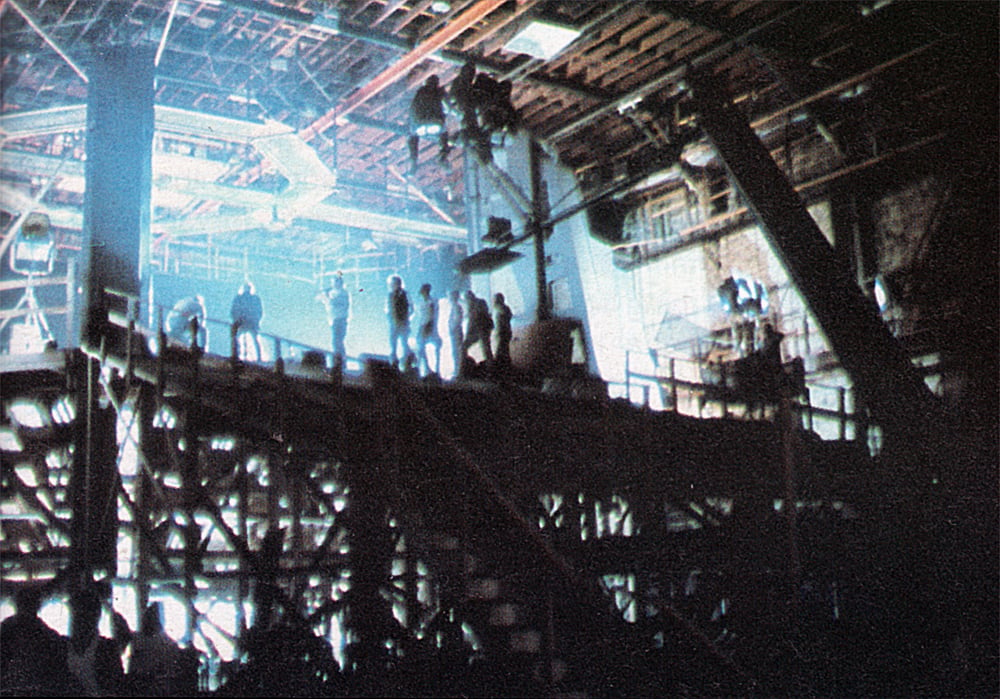

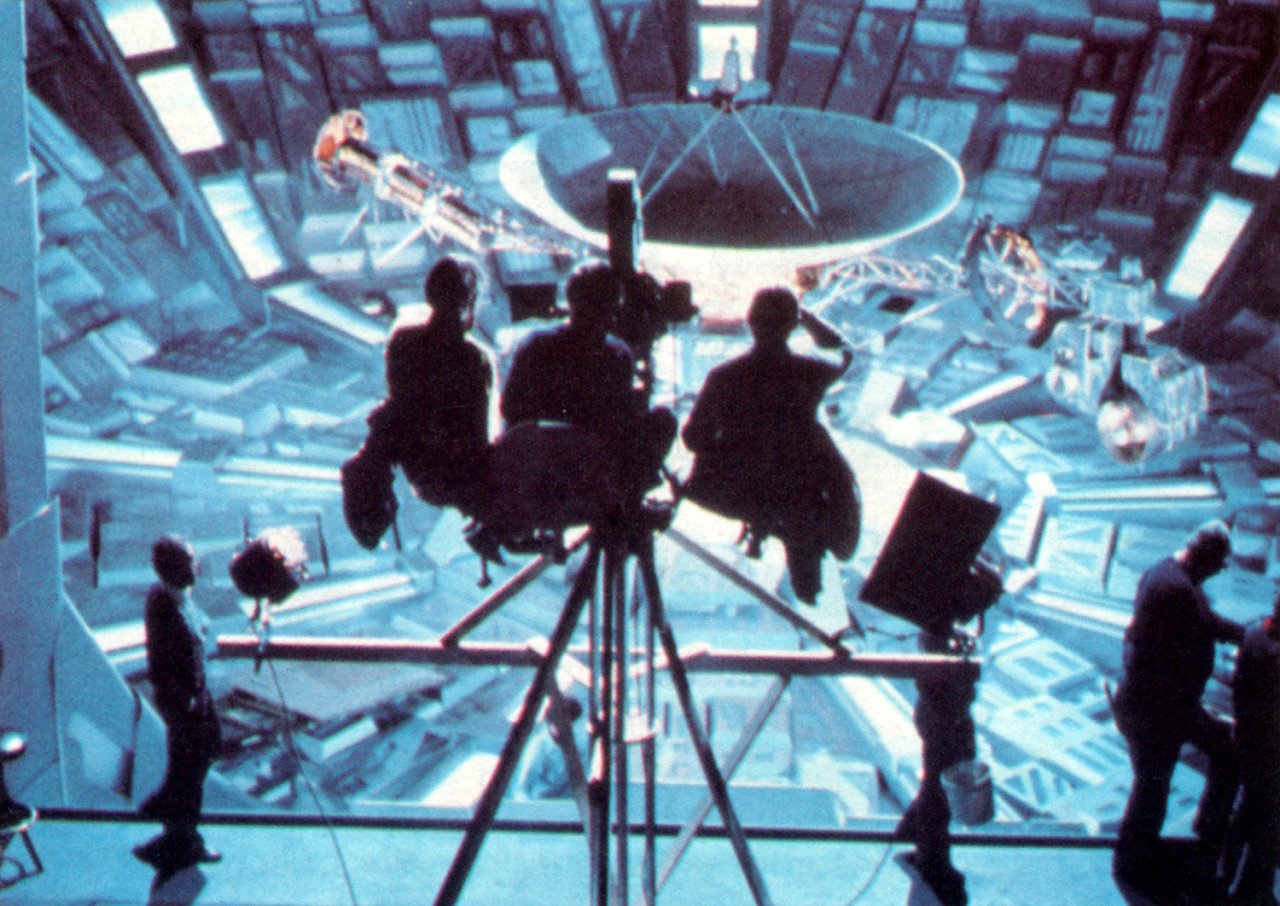

HMI lighting was used quite a bit in photographing this feature, and it was projected directly into the set — not bounced, as with soft light. For one specific sequence at the end of the film, in what was known as the “V’ger” set, we used practically every HMI light in Hollywood. Also incorporated into this unique set were projected lights that were designed by two very able technicians, Sam Nicholson and Brian Longbotham. All of these elements, combined with quite a few matte shots created by Doug Trumbull in post-production, resulted in an interesting effect. We all put our heads together to come up with something quite unusual.

Speaking of HMI lights, we fortunately did not have any flicker problems (and this was before flicker meters were available), but we did have grounding problems and we almost lost an electrician through electrocution. I think there is still a bug here and there in relation to the safety factors of HMI, but the principle is superb and I love the light. I’m very cautious with the HMIs from the standpoint of safety, and I do hope that at some point in the near future, the safety factors will be improved and the cabling made less dangerous.

One of the reasons why we used the HMI light inside was to achieve a blue cast, which we wanted, and we shot without corrective filters. However, throughout the sequence there were many color and light changes, which were achieved by means of gels that were slipped on and off the lights during the scene. For example, two lights with shutters would often be set up side-by-side. The shutters would be synchronized so that one opened as the other closed, thus giving us desired changes in light value or color value or intensity. We switched from red to green to blue to glaring white light, and we had a marvelous relationship with the Rosco people, who provided us with many different colors of gels. Their representative, Mike Niehenke, was on the set almost every day, asking what we needed and making sure that it got there. As I said before, we were not able to do proper pre-planning, so that’s why we needed the Rosco people to be at our beck and call as we went along, and they responded brilliantly. I don’t have any statistic on the amount of gels that we used, but we went through roll after roll. They even had to send to the East Coast for extra supplies, because they didn’t have enough here to meet our demands. The bill was enormous.

When the astronauts penetrate the alien entity, they emerge from the Enterprise and walk across a pathway of stones that are suspended in air. We shot them doing this, but the scene was enhanced in post-production by means of miniature artwork. After they cross the stones they arrive at a glaring mound, which is “V’ger.” They don’t know what it is at this point, but it glares and has a mystic aura about it. They ascend an area, arrive on top and look down into a bowl that is the V’ger site. They descend to explore and that is the moment when various things begin to happen. There are color changes and density changes and other elements are flashing. There are some marvelous pyrotechnics, but not like those we’ve seen before in science-fiction films. This has a real poetry to it and there is an intrigue that completes the story and explains what has gone before. Again, this is where we used HMI units exclusively, in combination with the projected light images by Nicholson and Longbotham.

Despite the low light level that I used in photographing most of the scenes, there was absolutely no forced-developing in the picture — not one foot of it. We used high-speed lenses and, also, the laboratory helped us out so that we were able to function without building up grain. All of our shots that were to include effects to be added later were filmed in 65mm for optimum original quality, but in using the 65mm cameras, we did not have the super-speed lenses that are available with the normal Panavision complement of sophisticated equipment. This meant that we were limited as to the lenses that we could use. We did have a couple of lenses — a 40mm and a 50mm — that were fairly fast, but even here we avoided forced development and, throughout our entire filming, utilized the printing range for achieving normal exposure.

My reason for not forcing the development is that, despite what one hears to the contrary, there is a certain degradation of the image, even at a one-stop push. My feeling is that if the entire picture is pushed, then you have nothing to compare it to and the forced development can be magnificent, but I am talking about going to another generation for post-production and that’s the reason we didn’t want to compound the build-up of grain.

Regarding the split-diopters that I mentioned using, I feel that the set-up Panavision has for these auxiliary elements is the only one of its kind in existence. They have a marvelous range of diopters fitted into rings that are easily slipped in and out. They also have unmounted ones that we could tape on or just hold by hand. Quite often, by just hand-holding the diopter, it could be slipped very gently as the operator looked through the lens. The Panavision set-up for diopters is magnificent and I use them on practically all my shows. I first learned about them when I did The Andromeda Strain with Bob Wise and we used them for about one-third of the shooting. Since then I’ve gained a lot of experience with split-diopters and feel very comfortable with them. We certainly used them constantly on the Star Trek feature.

The bowl-shaped V’ger set was constructed of moulded plastic material that really was not as strong as it should have been. Consequently, we could not dolly inside it because it would not stand the excess weight. Instead we used the Chapman Titan crane exclusively, which gave us a nice floating motion, the freedom of slipping right and left and up and down again. It is a superb piece of equipment and it worked perfectly for us, enabling us to move in almost any direction we wanted.

We used prime lenses throughout the filming, except for a couple of isolated shots where a zoom lens was necessary. But this was a picture that called for prime lenses. It has a prime lens look and feel to it.

Filters were used very selectively in the shooting, ranging from heavy fog to low contrast, but they weren’t used exclusively. We wanted a sharp look and I think it would have been wrong to shoot the whole picture with low contrast filters. We used them in specific segments where we wanted to create a softer mood or a flarey effect and we used both fog and low contrast filers. When it comes to fog filters I prefer the Tiffens because they have a more graduated range than the other lines and one can fine-tune the degree of softness better with them.

There was one very tricky effect that we shot in the principal camera, rather than doing it in post-production. Persis Khambatta is shown inside a sort of unique cubicle taking a “sonic shower” to cleanse herself. The intent was for her to appear nude. You see the form of her body but no details. You see her nude silhouette and then, at some point there is a change of light and we all of a sudden see her fully dressed. She opens the door of the cubicle and steps out wearing a kind of silver tunic.

In order to get the effect, we utilized the front-projection technique involving 3-M Scotch-light material. We had the form-fitting tunic made out of the 3-M material, then put her in the cubicle and projected flesh-colored light through the beam-splitter onto her body, using a Rosco gel. She went through the various motions of taking the sonic shower, with a ripple pattern projected onto the face of the cubicle. That was created by means of a rippling device, with waves of water in a pan reflected into a mirror and then through the beam splitter. We turned off the sonic rippling device by means of a shutter and simultaneously turned off the flesh-colored light that was being projected onto her Scotch-light tunic. The light was now normal and she stepped out of the shower cubicle wearing the 3-M tunic that matched the silver outfit that she usually wore.

Because of the fact that we had to light the principal action to match illumination coming from effects that would be created much later in post-production, there was necessarily considerable guessing going on. Most of this guessing transpired during the filming of the sequences on the Bridge. We had to design ambient light that was supposedly coming from viewing screens that had some activity on them, so it became a matter of coordinating various colors, the intensity of light and the type of light to match a complex set of sequences. We had to set up multiple lights with dimmers and shutters and some flashing devices that would form patterns on the faces of the actors or the bulkheads of the Bridge. Generally they would build up and then taper off.

There were some sketchy, not totally complete descriptions of suggested effects that were incorporated into the script. The writers gave us a kind of hint and then left the rest of it up to us — to Bob Wise, Harold Michelson, Doug Trumbull and myself. It’s awfully hard to put into words something in a science-fiction vein that exists primarily in the imagination and it did take a lot of talking for us to get our heads together and discover what to do. I think that we guessed well in most instances and gave the post-production units something safe and effective that would provide them with the flexibility they needed to create what had not yet been created.

Photographing Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a tremendous challenge and a lot of hard work, but I can’t emphasize too much how enjoyable it always is to work with Bob Wise. He knows every phase of filmmaking and, consequently, that makes our work easier and we can do a better job. There is never a time when you can’t go to Bob and get a definite answer to any question you may have. He’s always present; he’s always thinking about the picture; he’s always working ahead with the sketch artist or the Production Designer or the effects people. He’s very close to his editor, having been a top editor himself. He’s abreast of every element while you are filming. He’s very considerate with actors. He’s a perfectionist who will not settle for second best, but he also knows when you can go just so far in trying to get the best result. So he’s not unrealistic. He’s extraordinarily creative and, to my mind, the complete director.

This story retains the original text and style as it was originally published. The original 1980 issue of AC contains much more material about the making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture and is available to AC Archive subscribers.

In 2022, a new 4K reconstruction of the “Director’s Edition” of the picture — overseen by Wise — was released, featuring additional visual effects and improved image quality.

Read more stories in our Trek retrospective collection here.