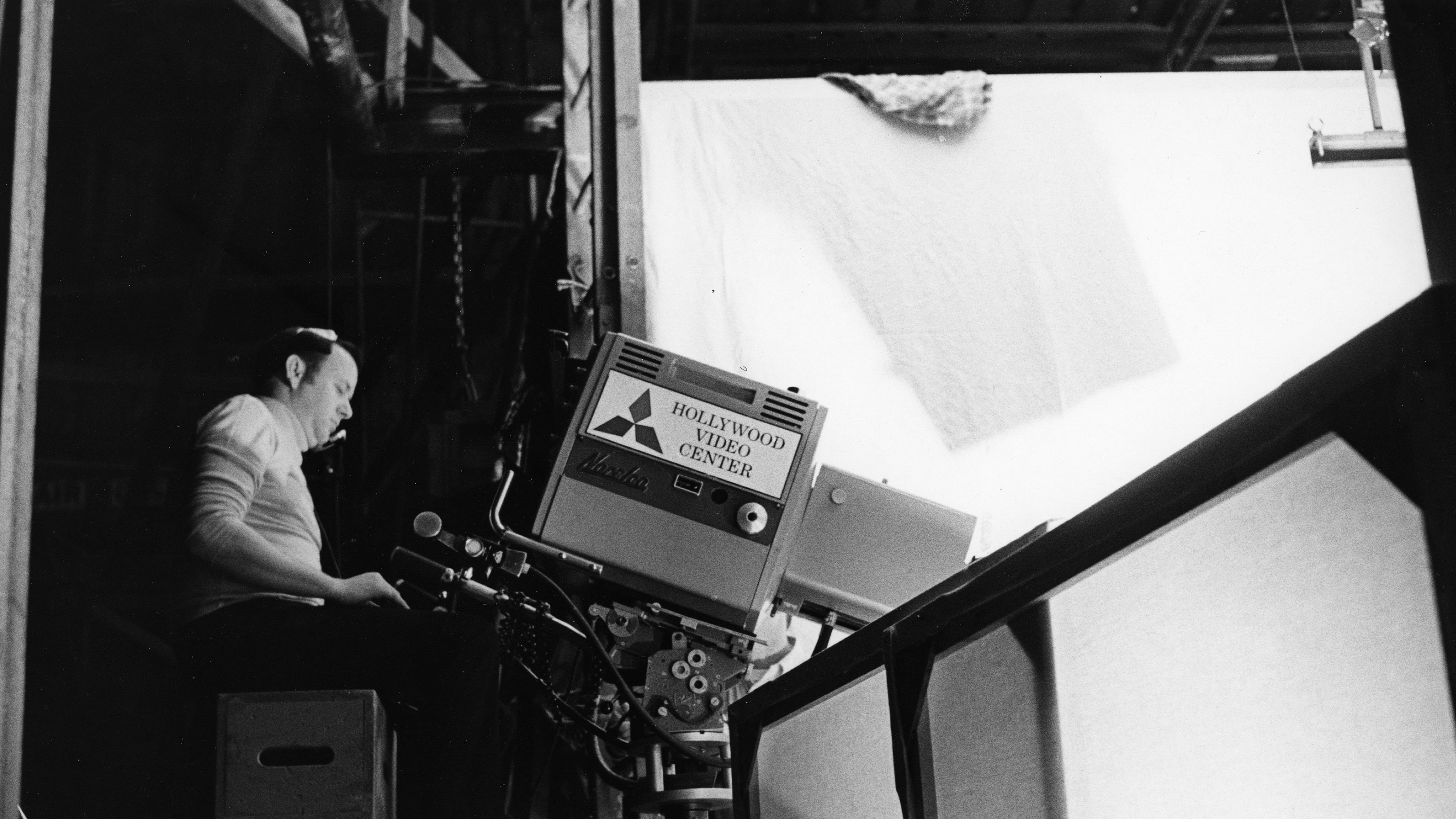

Photographing The Andromeda Strain

A student’s-eye-view of the behind-the-scenes world attendant to the production of a super-dramatic “whatdunit” science-fiction thriller based on a best-selling novel.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jon Bloom is a Communications student at Antioch College, with a major interest in Cinema. As part of a work-study program, he took a sabbatical from formal academic courses in order to accept an assignment as production assistant on The Andromeda Strain. In this capacity, he did a variety of jobs during the entire preproduction and shooting phases of the film, thereby gaining an opportunity to experience a complete over-view of professional feature production. The accompanying article is based on his observations, as a student, of the extremely complex technology involved in the making of such an unusual feature.

The Andromeda Strain, brought to the screen for Universal release by producer-director Robert Wise, is an off-beat thriller based on Michael Crichton’s best-selling novel of the same name. Although it falls within the category of science-fiction, it should, more accurately, be designated as sciencefact, because Andromeda is a story having a basic premise that is all too real. It projects an account of what could happen if an unknown and deadly outer-space organism should enter Earth’s atmosphere to plague its inhabitants. Just such an epidemic is greatly feared by present-day scientists — as witness the strict enforcement of a two-week isolation quarantine for American astronauts returning from the moon.

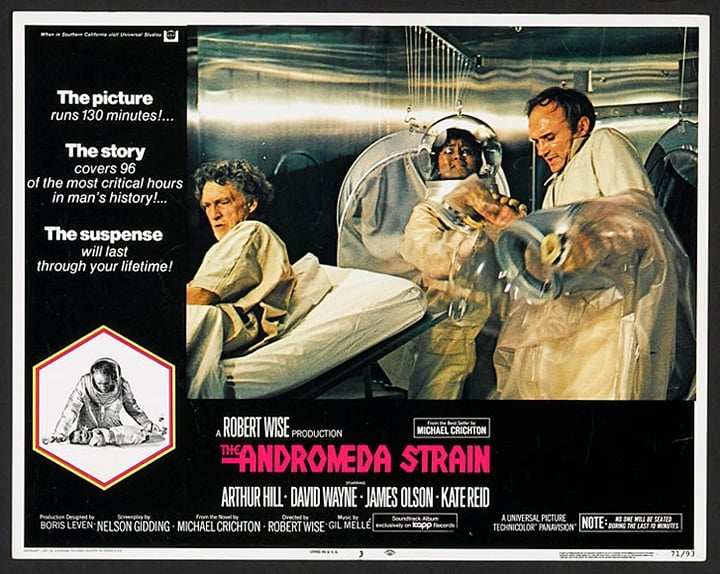

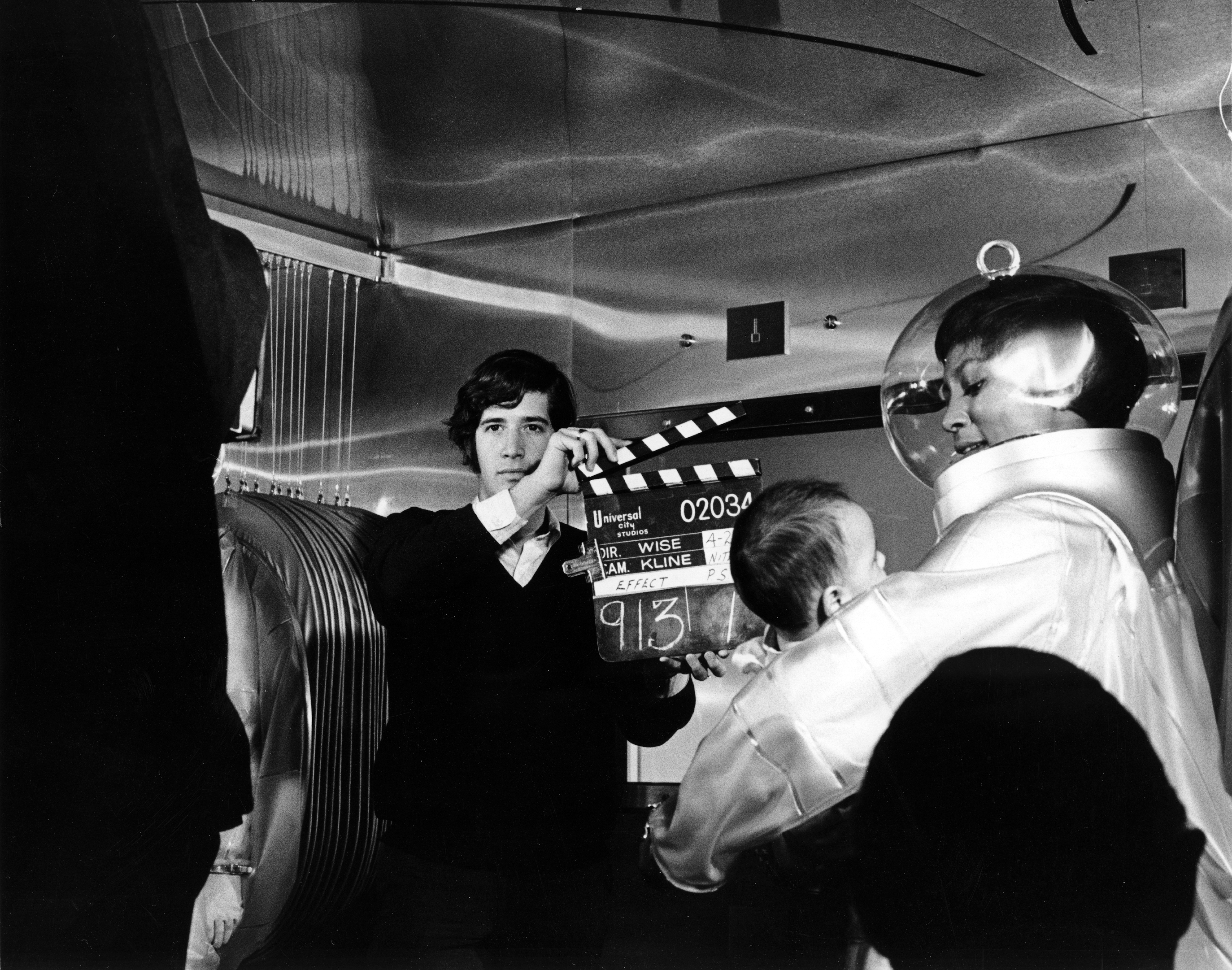

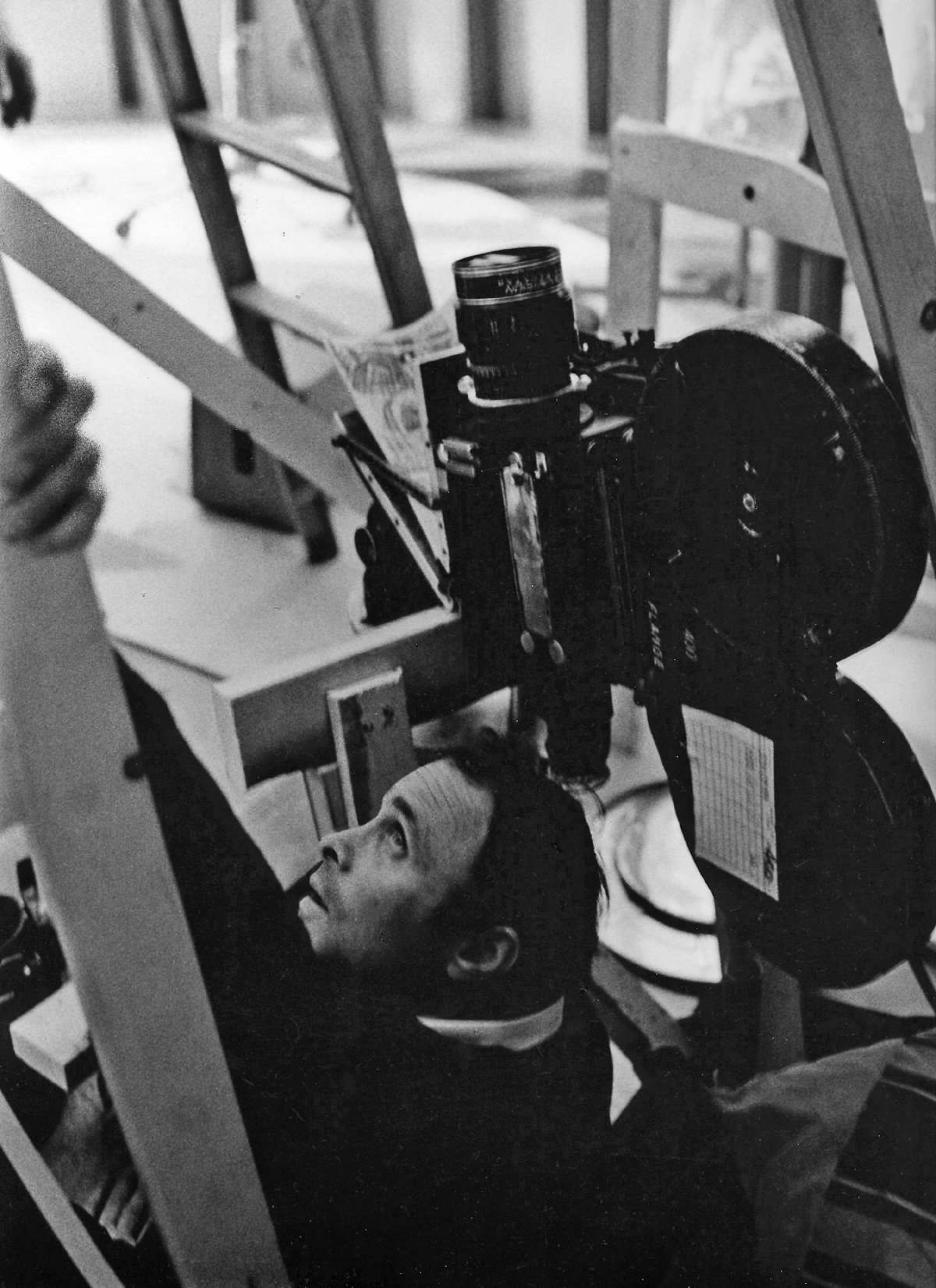

As written for the screen by Nelson Gidding and suspensefully photographed by Richard H. Kline, ASC, the film documents the results of an epidemic crisis which occurs when a lethal extra-terrestrial micro-organism descends to Earth aboard a returning space probe capsule, instantly wiping out all but two of the 48 inhabitants of a remote desert village. The Project Wildfire Alert, previously established by the government for precisely such an emergency, is activated. A team of four distinguished scientists is called in to a top-secret laboratory to race against time in an attempt to characterize, contain and exterminate the deadly space organism.

Wise, for whom the project marks the 34th picture in a phenomenal career, waited almost two years before finding in Andromeda the kind of contemporary story he had been seeking as a change of thematic pace from the period backgrounds of his last three ventures. “Andromeda,” he points out, “in many respects parallels what has been going on at the lunar receiving laboratory and is very much ‘now’ — about as contemporary as it is possible to get.”

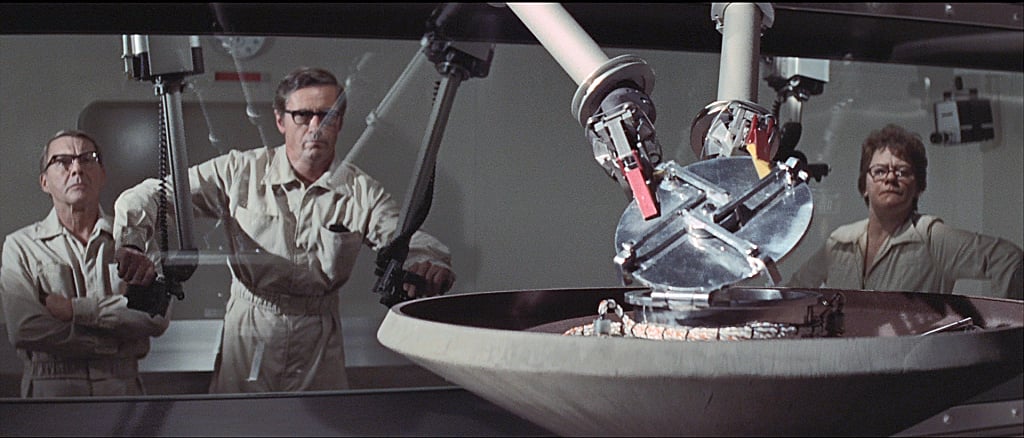

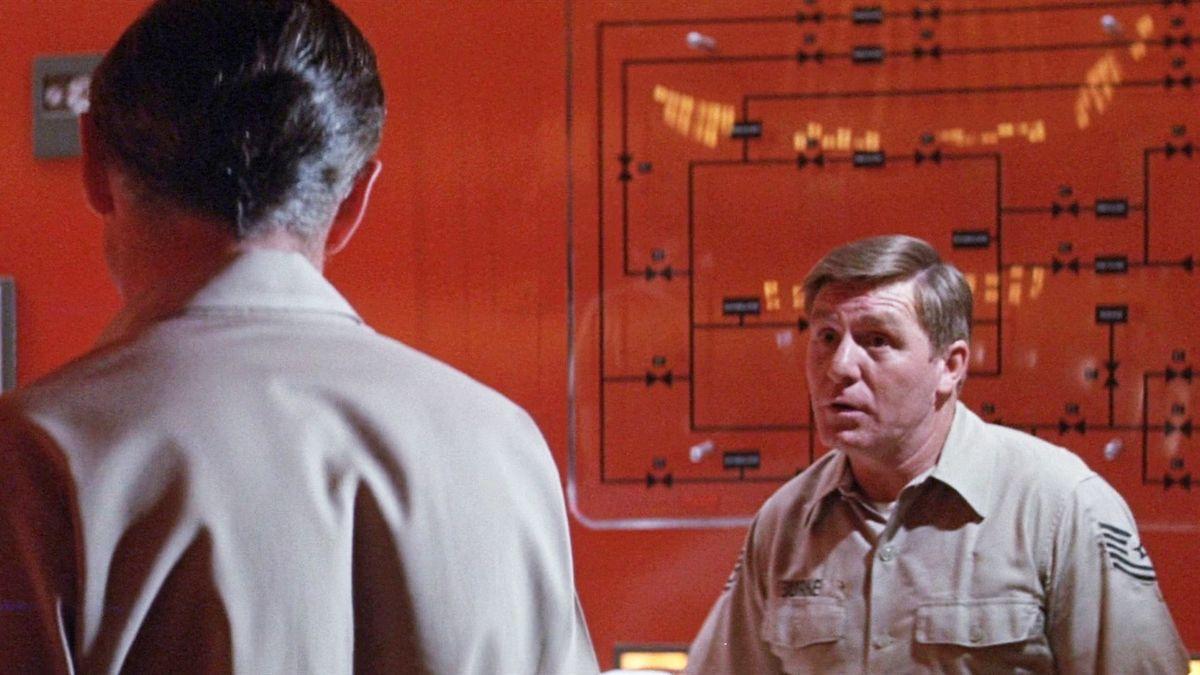

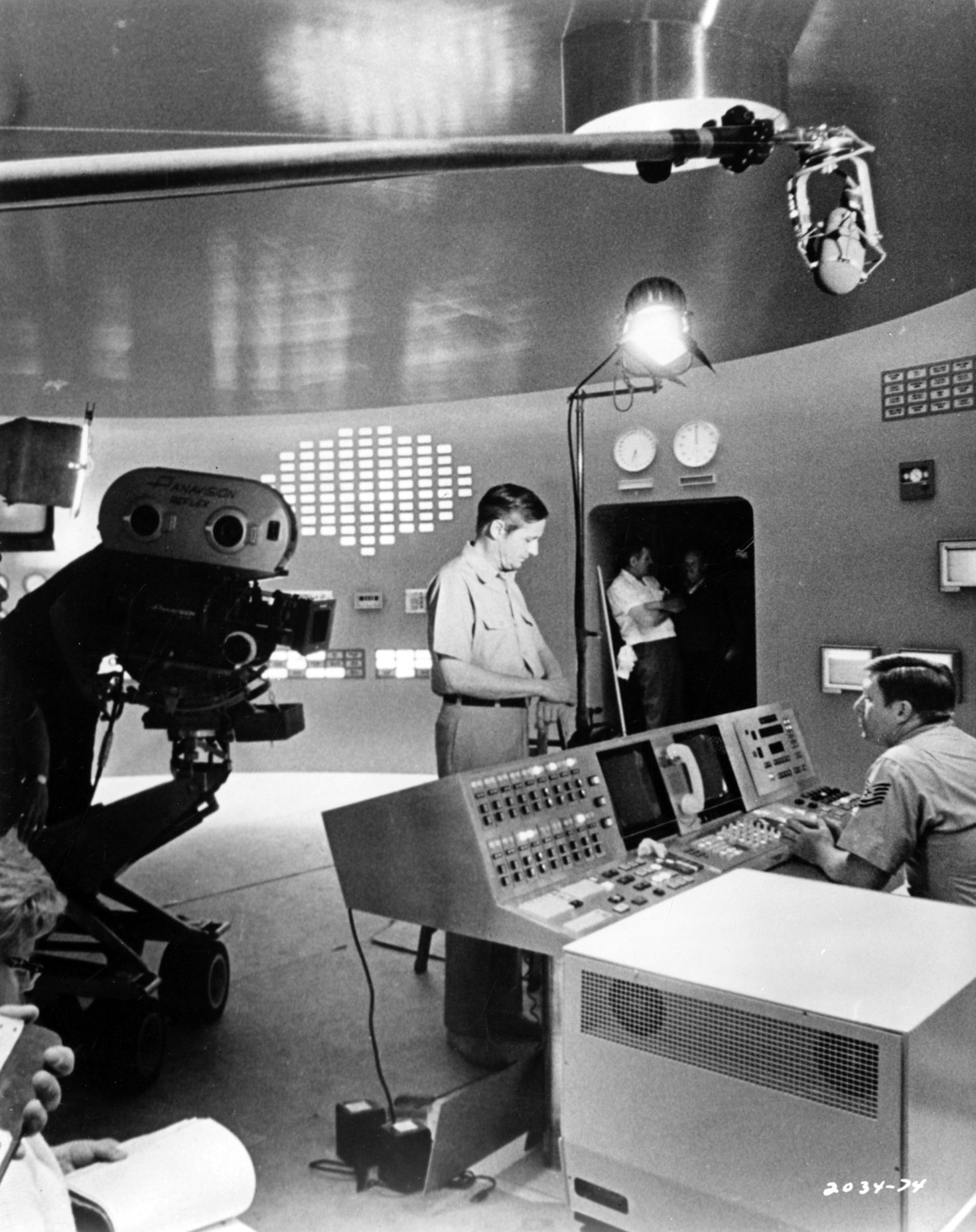

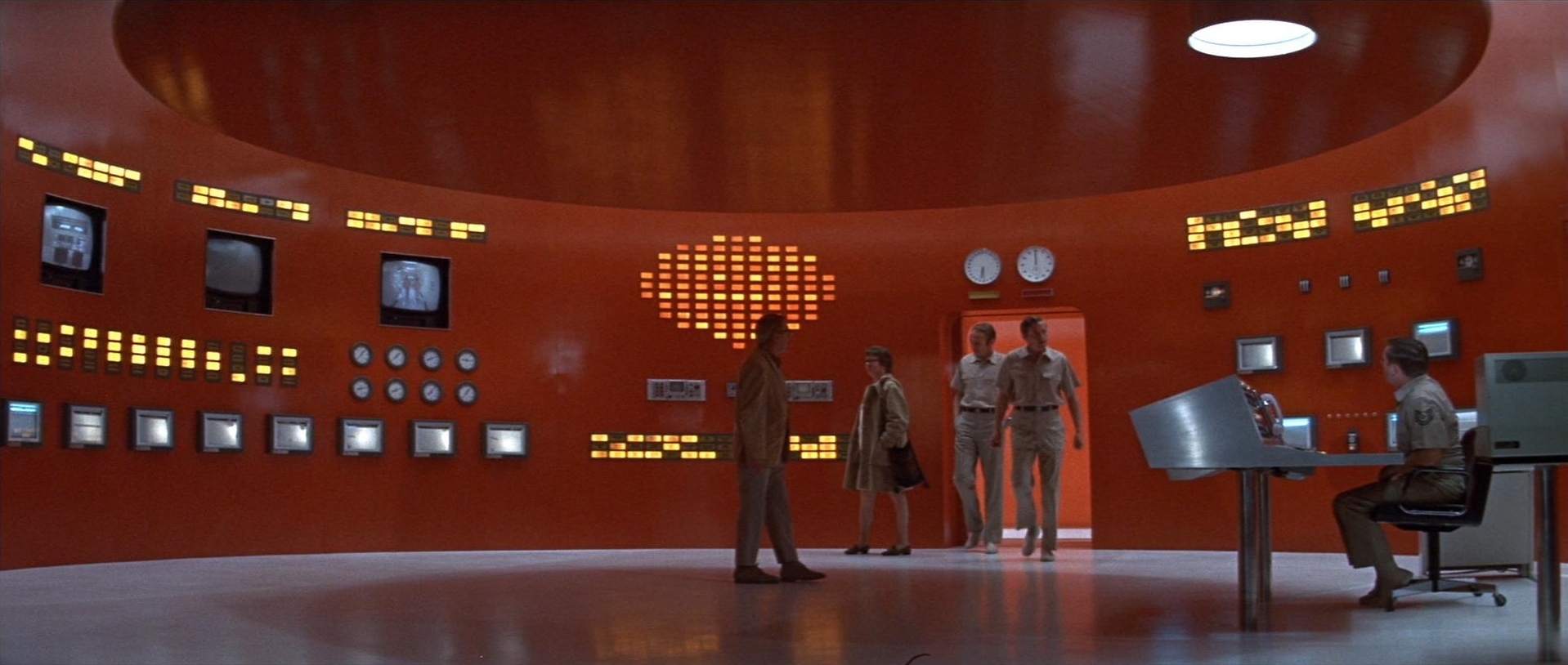

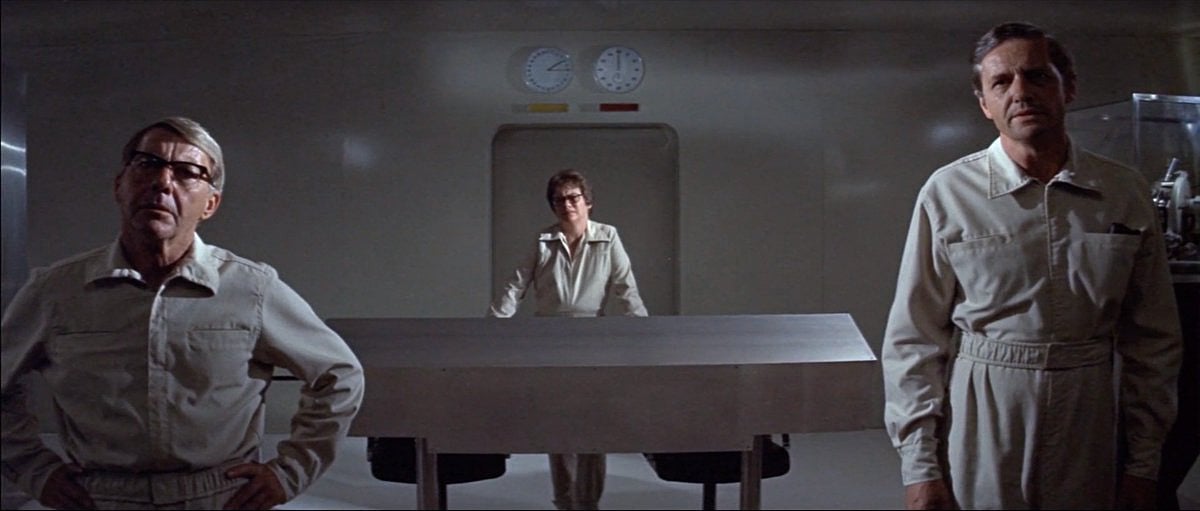

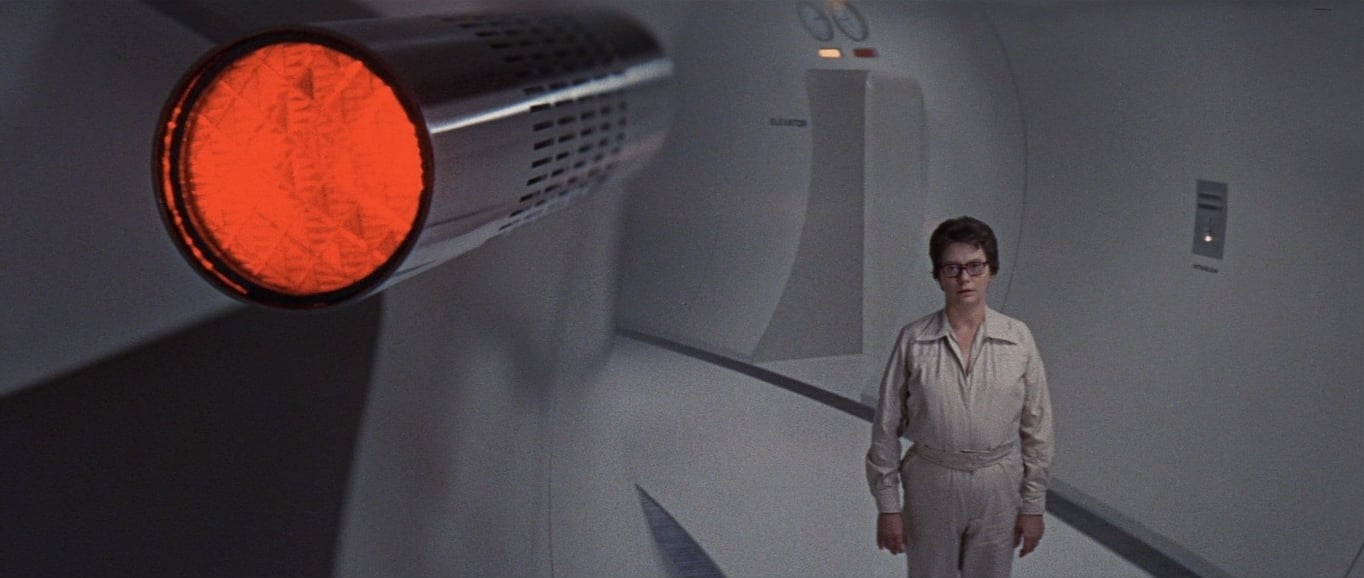

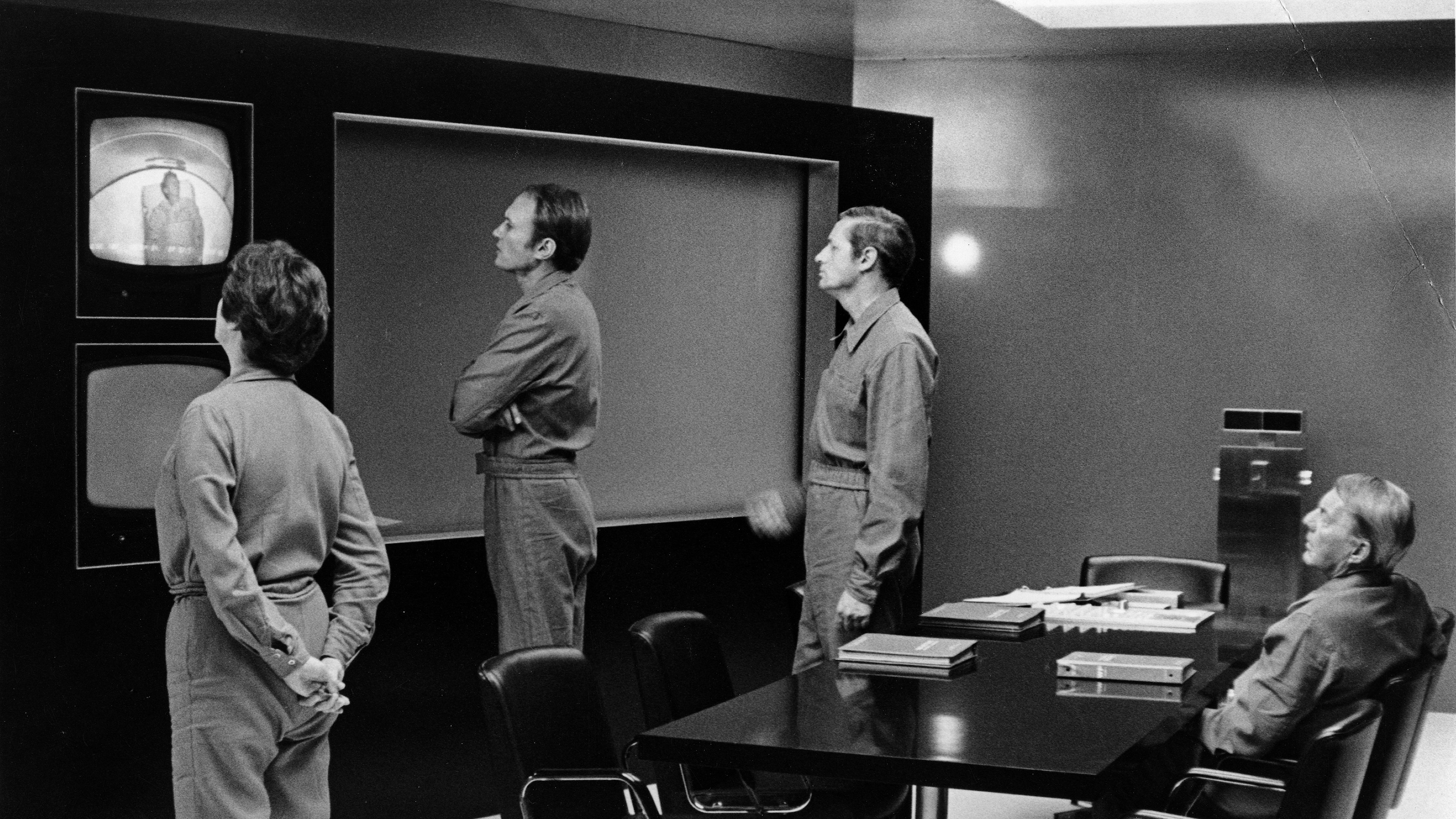

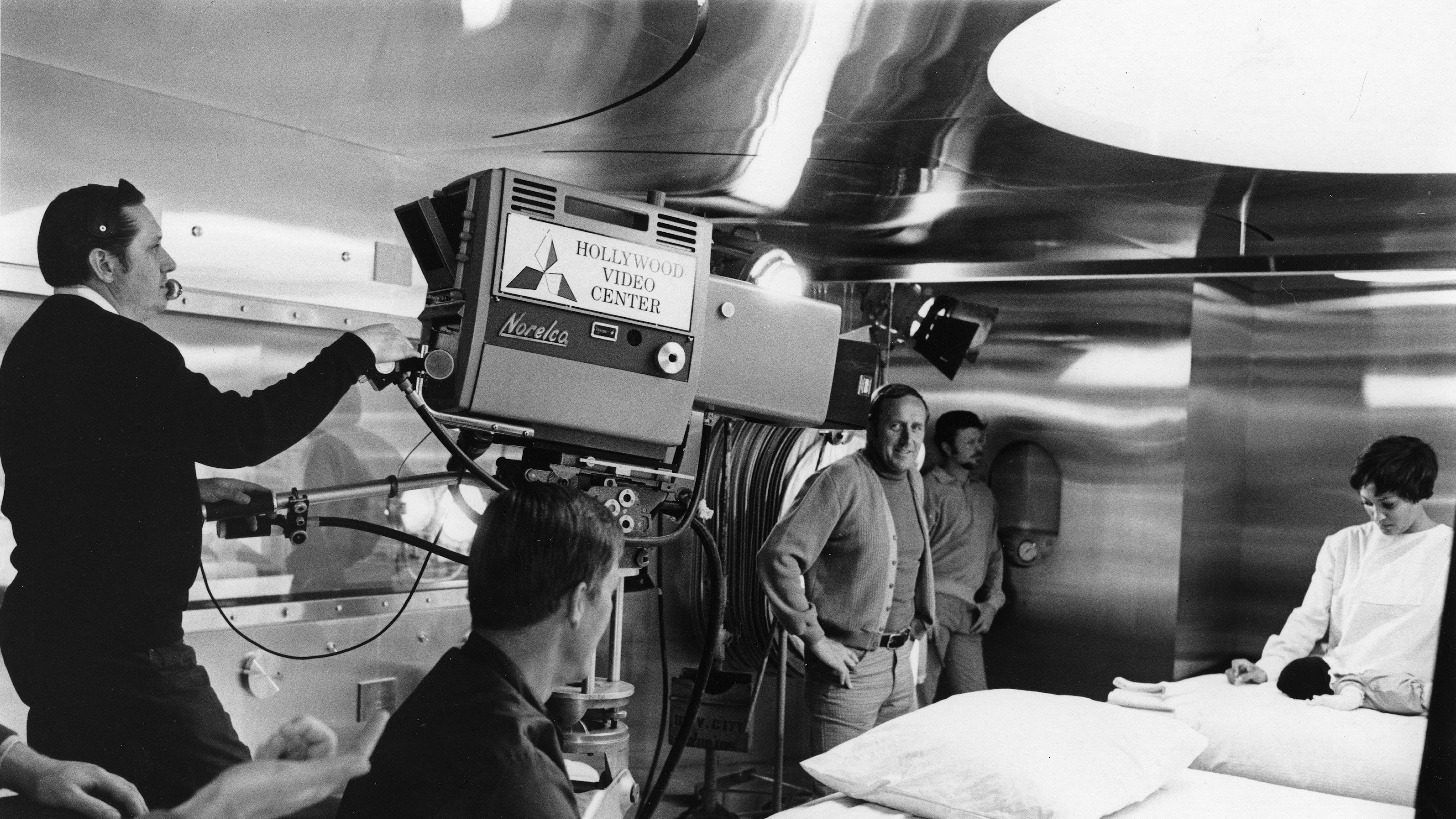

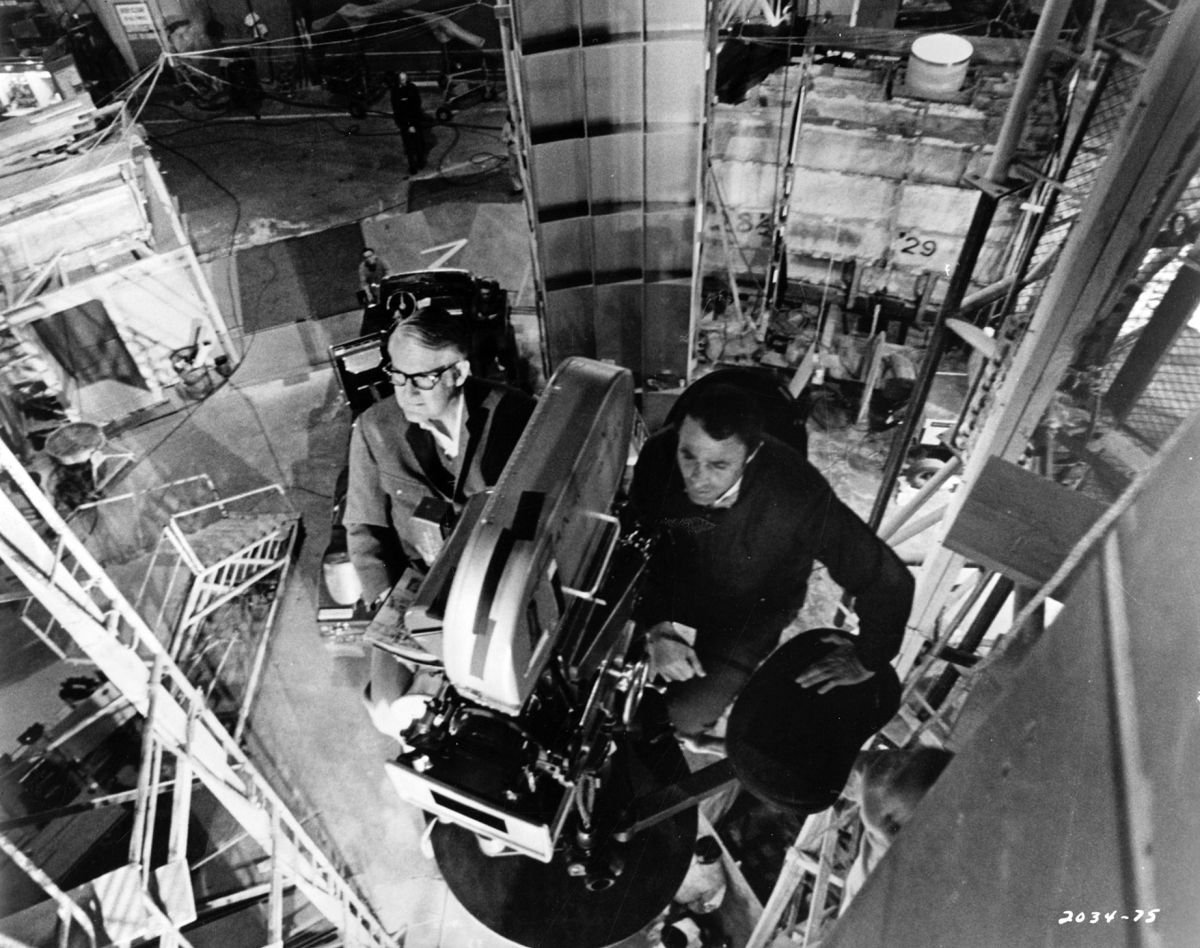

The Wildfire research laboratory, the main setting of The Andromeda Strain, is a completely sterile, five-level, underground facility equipped with the most sophisticated scientific and technological tools known to man. The set constructed to represent it was one of the most elaborately detailed interiors ever built and occupied almost every square inch of Universal’s cavernous Stage 12, which, large as it is, proved to be not quite high enough to accommodate the soaring five-story central core of the structure.

It was necessary to excavate 17' into the floor of the sound stage in order to erect this 70' set element. Its construction alone represented an expenditure of more than $300,000. A complete 360-degree circular corridor, 1/8-mile in circumference was also constructed to simulate the corridor of the underground emergency laboratory. An additional $4 million-worth of the most advanced scientific equipment, loaned by facilities from all over the world, was used to “dress” the sets, which were conceived by production designer Boris Leven, an Oscar-winner for his contributions to an earlier Wise production, West Side Story.

“Robert Wise is the most complete director that I have ever worked with.”

— Richard H. Kline, ASC

For director of photography Kline, Andromeda represented a radical departure from previous feature assignments, including the Academy Award-nominated Camelot, The Boston Strangler and Gaily, Gaily. Though the visuals of the picture flow in seemingly effortless fashion across the screen, Kline regards it as his most difficult challenge to date, in that he was called upon to lens several effects which had never before been photographed for a motion picture.

The diverse demands of The Andromeda Strain also took the company on location for over a month in Texas and California. Principal location sequences, simulating the isolated village of Piedmont, New Mexico, where the space probe satellite lands, were filmed at the near-ghost town of Shafter, Texas. Three weeks in February, 1970 were spent on location in the little Southwestern Texas town. Shafter underwent considerable face lifting to transform it into the stricken hamlet in which the Andromeda crisis originates.

Another location sequence, the agricultural station which hides the secret entrance to the underground lab, was filmed at Ocotillo Wells, California. The agricultural station and surrounding planted fields were especially constructed for the film.

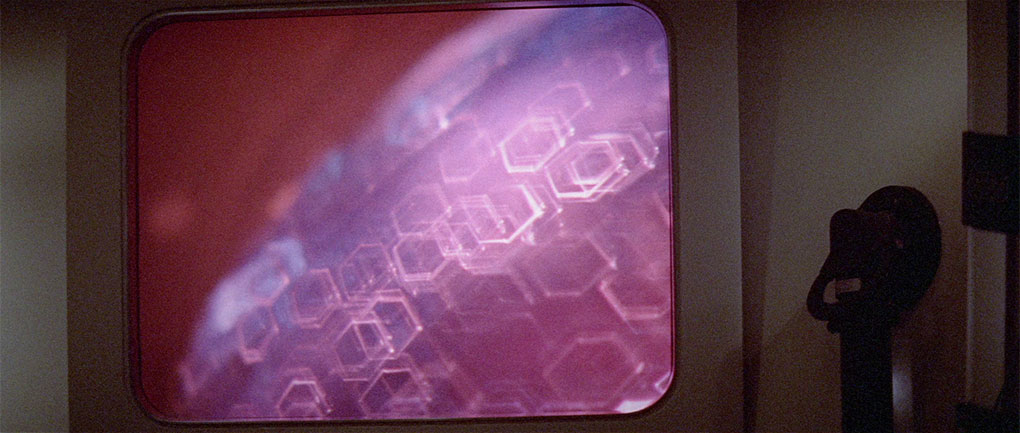

The visual impact of the dreaded microscopic organism was deemed so vital to the suspense drama, that $250,000 was allotted for the creation of special photographic effects by Douglas Trumbull of 2001: A Space Odyssey fame, and James Short. Trumbull “imagineered” the germ’s appearance, which in the story was seen on microscope and computer viewing screens at enlargements of up to one million times.

The major task for Wise in making The Andromeda Strain was to re-create the sense of utter reality which made the novel so successful. Kline had an important role in making the motion picture appear as an authentic, on-the-spot film-record of the five-day biological crisis. His efforts and creativity gave the picture the conviction of documentary footage.

Michael Crichton’s 1969 novel was popular because he had succeeded in making the story seem very real. The book was printed and laid out to look exactly like a government document, replete with “Top Secret” stamps, and warnings about the report’s highly classified nature. The book contains complex illustrations, charts, diagrams and graphs, most of which are far beyond the comprehension of laymen, but not really essential to understanding the plot. These illustrations helped to give seeming complexity to the novel. Crichton’s trick of citing imaginary authorities and the inclusion of an impressive reference bibliography (entirely fictional) added to the novel’s credibility. Written in a style which seems official and authentic, the book is nonetheless engaging and exciting. All these techniques worked together to present the story in the form of an authentic government report, released to the public. The goal of the film was to create that same sense of actuality and authenticity that so permeated the novel. Novelistic form is similar to filmic form in many ways. Style and mood in film, as in a novel, are created by many illusive techniques, which blend together to create an overall atmosphere.

In The Andromeda Strain, many things worked together to create a mood or feel of reality. Wise’s direction, the script, the editing, the acting, the art direction, the electric non-musical score; all these components — and, particularly, Kline’s cinematography — combined to create in The Andromeda Strain a unique synergistic reality, a sense of total believability — for the film as a whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Andromeda was strongly influenced by the need to make the film seem non-fictional. The four lead roles of scientists, played by Arthur Hill, David Wayne, James Olson and Kate Reid, were filled by very competent actors, although not “star” names. Wise purposely avoided casting superstars for the film because he felt they would be recognizable as themselves rather than becoming the characters they portrayed.

The story itself is complicated and scientific. It called for the photography of many unique processes and machines that had never been filmed before. Computer and microscope screens, and many other special effects needed to simulate actual scientific devices and processes, were essential to the story. Kline made many tests, trail-blazing new techniques, in discovering methods to meet Andromeda’s unusual visual demands.

When Kline began pre-production preparation and testing in January of 1969, Wise told him that he wanted The Andromeda Strain to have a “documentary look.” Color negative film gives beautiful results, but both Wise and Kline felt that eliminating the film’s high polish would help create the overall realistic effect they wanted.

Toward this end, Kline began experimentation to give the Eastman 5254 color negative a more pronounced grain. In conjunction with Technicolor, he experimented with the addition of grain to the positive print. Results of these experiments were disappointing.

Next, he experimented with a process commonly used to increase film sensitivity in poor light — forced development. Tests were shot, pushing the film one, two, and an unusual three and four stops in development — which proved to be too much. A two-stop forced development was just right. It dulled the inherent gloss of the film stock and produced the reality look that Andromeda needed. A beneficial side effect was greater depth-of-field, as the lens would be stopped down. The entire film was forced two stops.

Technically, pushing two stops means that the raw stock is two stops underexposed in the camera. Then, in the lab, the film is over-developed two stops to compensate.

“On location,” Kline explains, “the push helped to create the stark, barren, awesome look we wanted, while in the laboratory it contributed to the sterile, blank, icy look the story needed.” He summed up by saying, “The two-stop push gave us the documentary texture we were after without resorting to a sloppy kind of photography. The film still has a rich professional look, but an appearance which is very different from the ordinary, and one that works well for the picture.”

The sets and locations of The Andromeda Strain were perhaps the most important factor in achieving complete verisimilitude. However, they also created special problems for cameraman Kline. As the production began, Wise said, “The sets are the stars of Andromeda” — and they most certainly were. The backgrounds and settings were the biggest factor in establishing authenticity. It was essential that the underground laboratory, where over half the story takes place, look as though it really existed.

Production designer Boris Leven combined extensive research with imaginative design in order to create brilliant but credible sets. A big reason why the story seems so real is that the sets, in many cases, are functional and much of the hardware is operable. The story of Andromeda unfolds in two basic places: the town of Piedmont, New Mexico, and within Wildfire, the underground government laboratory. Leven, in cooperation with Kline, conceived basic color schemes for these two primary locations which were highly effective, although unobtrusively so, in conveying the moods the story demanded.

Piedmont, N.M., scene of the disaster, needed a dead, hot, barren look. Soft earth colors of browns, reds and yellows, along with unusual camera angles of townspeople suddenly killed by the germ, conveyed the desired feeling.

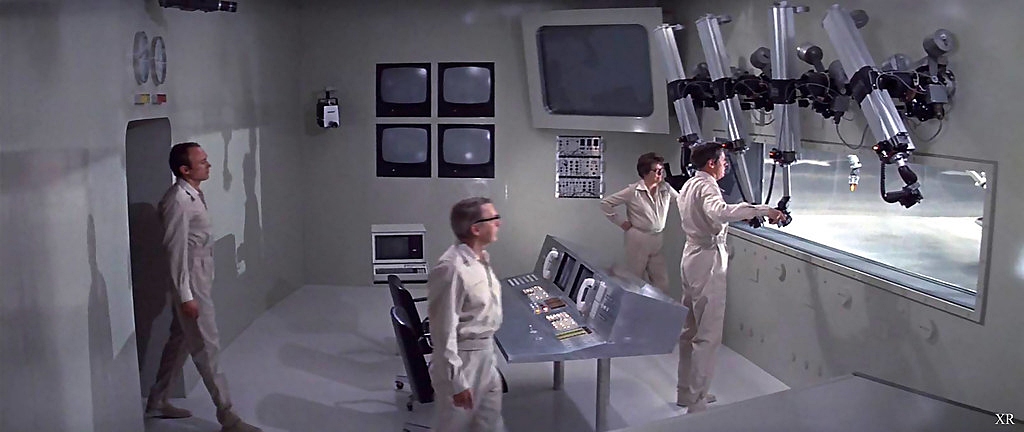

The tense, sterile, frigid feeling the laboratory sequences required was in sharp contrast to Piedmont. The Wildfire lab color scheme was designed with cool, low-key colors of blues, greys and off-whites.

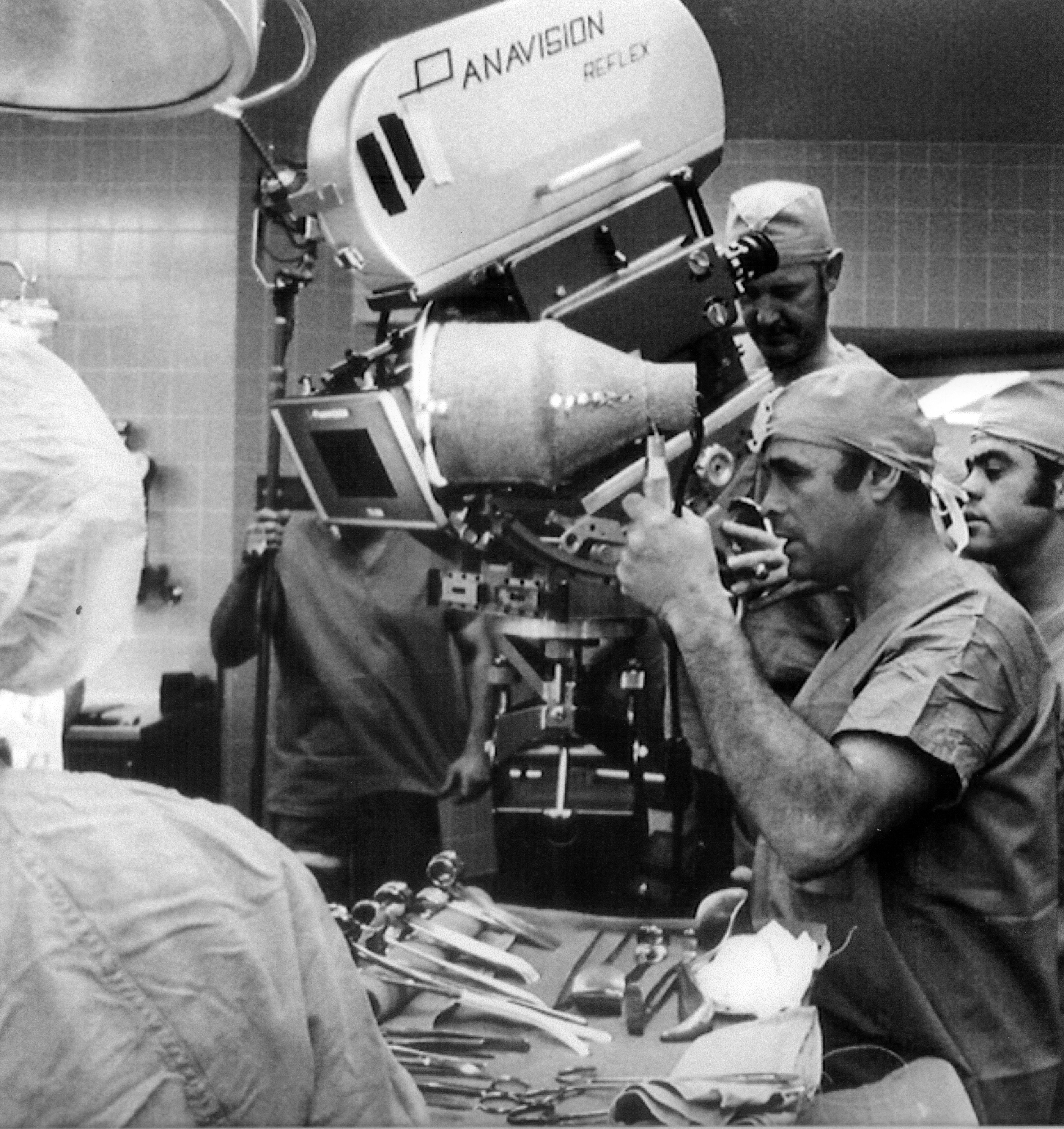

The laboratory sets were designed and built unconventionally. Almost all of the sets were four-walled and ceilinged, with very few wild (removable) walls, and they were provided with practical fixtures as well. These unique sets created photographic problems such as are rarely encountered in sound stage shooting, but the sets were built for realism, not convenience. The cinematography had to be adapted to the sets, making the use of realistic techniques a necessity.

Special demands were placed on the lighting utilized because of the enclosed sets. Said Kline, “To achieve an effective source lighting, the key light usually came from existing fixtures, and supplementary fill was provided by means of bounce light.”

On Andromeda, Kline worked at a low-key intensity because this makes it easier to balance light and use natural source illumination. Working at a very low light level, he averaged approximately 40 foot candles, which is about the intensity of ceiling fixtures, and sometimes dropped as low as 15 foot candles. Another reason for the use of such a low light level was that fixtures and illuminated buttons on consoles were important story points, and only at a low light level would these register well on the film. Also, the two-stop push increased film sensitivity and permitted the use of less light.

Each set contained expensive working scientific equipment, loaned by manufacturers to Andromeda. The equipment, valued at over $4,000,000, necessitated 24-hour guards on all sets.

In the laboratory sets the biggest photographic and lighting problem, or “challenge” as Kline called it, was caused by glare from high-gloss metallic paint. Indirect bounce lighting was an effective answer. A few Andromeda sets were constructed entirely from stainless steel used on three walls, floor and ceiling. These surfaces, which were extremely reflective to objects as well as any direct light had to be lit by means of bounce light only.

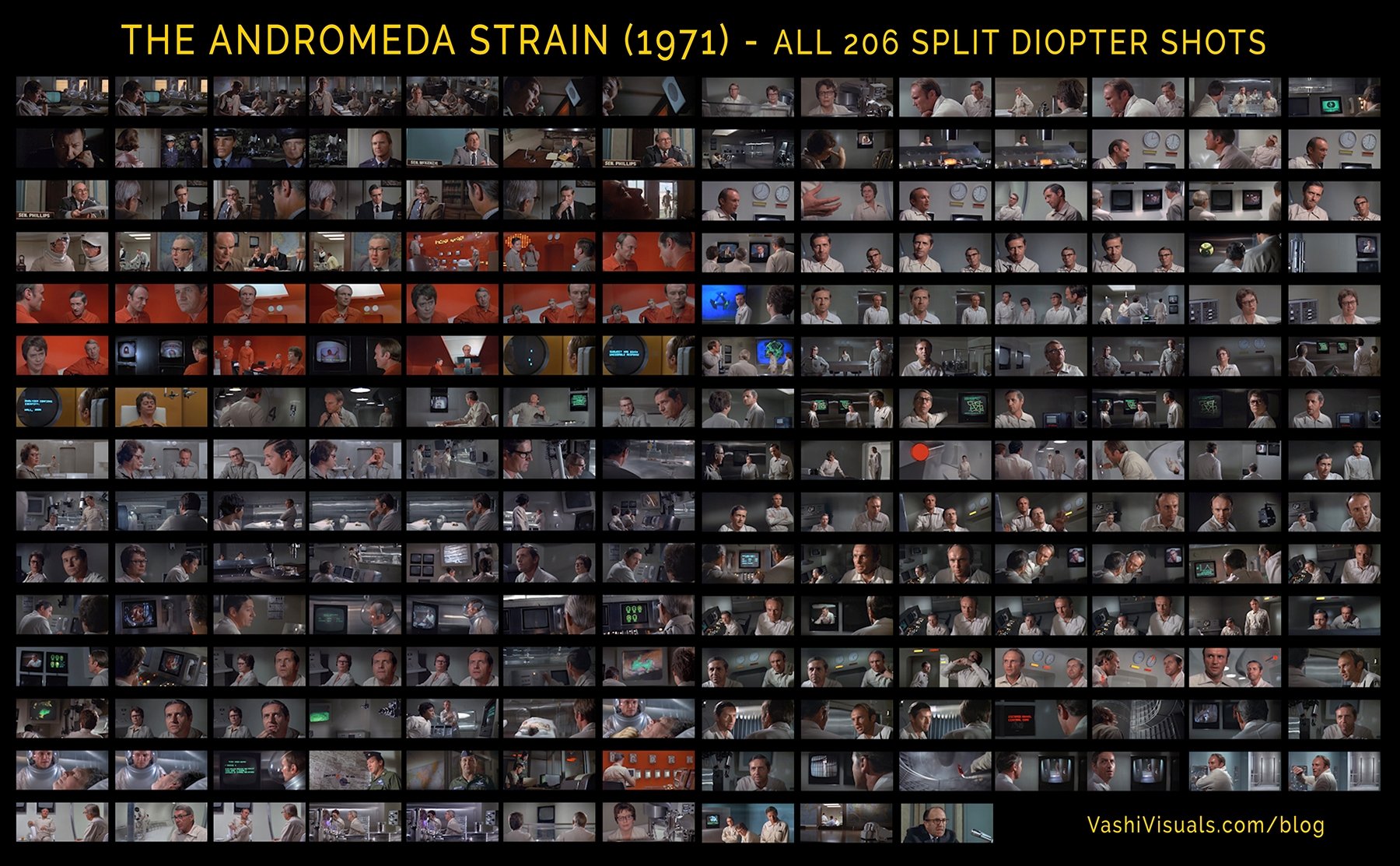

Extensive use was made of split-field diopters in photographing Andromeda. Split-field diopter lenses are partial auxiliary lenses, cut so that they cover only a portion of the prime lens. They may be compared with bifocals for human vision. They have an advantage over bifocals, however, in that they make possible sharp focus on both near and far objects simultaneously. Kline reported that more than half of the scenes in the film were composed as diopter shots. Split-field diopters are not new to cinematography, as they have been available for many years, but they have been rarely used because positioning is very difficult. To camouflage the edge of the split-field diopter it is necessary to position the edge on a vertical line of the set being photographed. Without a reflex camera, exact positioning could only be estimated, and camera movement was impossible. However, today’s new reflex cameras make possible perfect positioning and allow a constant check of the diopter's effectiveness during actor as well as camera movements.

Kline used as many as three split-field diopters in a single shot. They were even slipped in and out of the frame during the shot, particularly on zooms. Staging and preparing setups which utilized split-field diopters was, of course, quite complicated. The actors had to be cooperative because of the restricted area in which they could move. “Once we got used to working with the diopters,” says Kline, “there was virtually no extra setup time required. The sharp focus we maintained helped greatly in making the scenes look real and it also showed off the equipment and sets to best advantage.”

The split-field diopter allows the director great versatility in frame composition. Andromeda was shot in Panavision, which has an aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The advent of widescreen itself has been a boon to some directors because it has enabled them to say and show more within the frame. Diopters allow for even more versatile usage of the widescreen format and Andromeda proves the point. The picture includes numerous diopter shots which incorporate extensive actor and even camera movements, achieved by slipping diopters in and out of the frame. This technique permits unlimited new composition possibilities with increased depth-of-field.

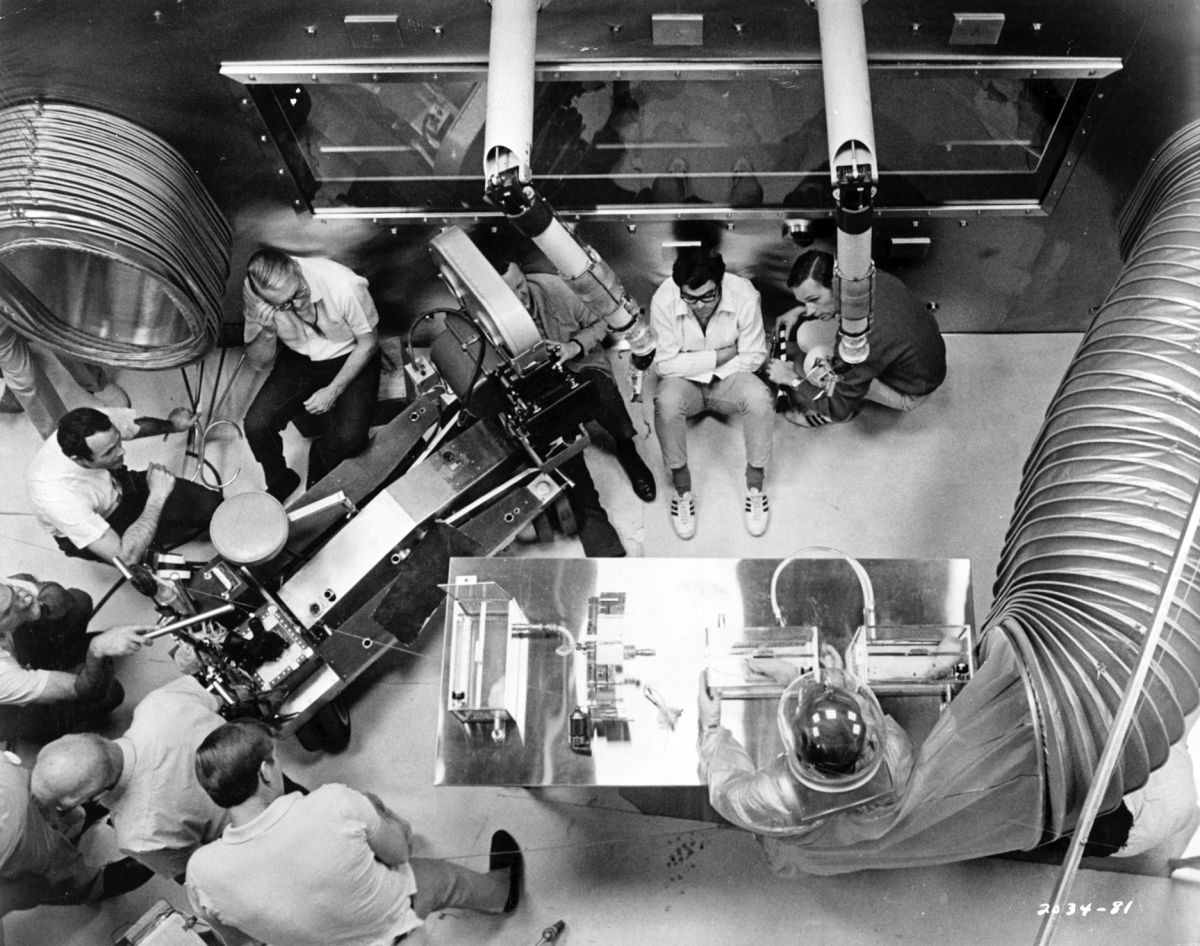

Doug Trumbull’s microscopic photography was rear projected onto laboratory viewing screens. In some shots, a total of four rear projections (two process projectors and two stereo slide projectors, projected on two different screens) were in use concurrently. These projectors had to be turned on and off according to cues.

“The main problem,” Kline explained, “was to maintain a color consistency in special materials made by Trumbull. The color values had to be correct and consistent, and the detail had to be very sharp. We usually worked at low light levels and Kelvin temperature and light intensity of the projectors had to be balanced with that of the lighting used in the surrounding set. The low light level at which we needed the projectors to work caused a distortion balance problem in relation to the projected images. We decreased the intensity of the projected light by placing ordinary single, double and triple scrims in front of the projector’s carbon-arc light source. This reduced the light output, but didn’t interfere with the image sharpness because the filtration was introduced at a point before the light reached the film.”

The opening scene of The Andromeda Strain takes place in the desert at night. Two Air Force technicians, sent to retrieve the space capsule, discover that the inhabitants of Piedmont have mysteriously died. This sequence was filmed day-for-night because the desert area was physically too large to light.

The tremendously bright blue Texas sky posed a serious problem. When the film was printed down the sky was still a bright blue, and the scene looked artificial. To overcome this, Kline asked Technicolor to duplicate a technique originally created by Deluxe-General Labs. A panchromatic black and white dupe of the scene was made. The color positive and the panchromatic dupe were then printed together. The panchromatic dupe was used as a kind of mask to desaturate the color density of the positive. This technique, in effect, partially substitutes varying shades of grey for the full-strength colors in the positive. Since the blue of the sky was the only strong color in the scene, the blue became toned down to a charcoal color. The result was an excellent night effect — so realistic, in fact, that this process will most likely become standard practice in shooting day-for-night scenes.

Nelson Gidding’s script for Andromeda made many new and special demands upon Kline’s cinematography. The story called for the photography of actual or simulated processes, events and objects which had rarely been shot before.

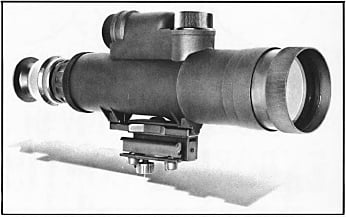

For example, in the opening sequence, a new viewing scope, called an N.V.D. (Night Vision Device) is seen. This device gathers available starlight and moonlight and actually enables viewing in near darkness. The N.V.D. is a light amplifier which magnifies brightness more than 40,000 times and then projects the image onto a photocathode screen within the scope.

Kline tested an actual N.V.D. to see if an acceptable picture could actually be shot through it. One evening, before the company began principal photography, he and a small crew made a photographic test on the backlot. Holding the N.V.D. in front of a macro lens, Kline filmed several tests. He bracketed the exposures to determine the best exposure level. Viewing the test footage, he was surprised to see that a correct exposure had been made in near darkness, through the N.V.D., shooting at f/5.6.

The image had a strong, grainy, green tint, accurately duplicating the effect caused by the N.V.D. photocathode. Then, on location, Kline repeated the same procedure to make a picture of the contaminated village of Piedmont.

The script called for a point-of-view shot supposedly made from a reconnaissance plane sent out to observe the village. “In view of the fact that we didn’t have a jet available,” says Kline, “and also because a jet would have flown too fast for the audience to be able to see what was going on, we took ‘dramatic license’ and mounted the camera on a Tyler Vibrationless Mount atop a Chapman Titan Crane extended as high as it would go. Using a 50-500mm zoom lens and combining the zoom effect with the movement of the crane, we were able to get a nice smooth motion pattern. I would tilt and pan the camera into the village, zoom in, and then lift up as if we were pulling away, racking the zoom back to its widest angle at the same time. The effect, without over-cranking, was a realistic simulation of a fly-over.”

A sticky photographic problem encountered during the filming of exteriors and actual interiors for the Piedmont sequence arose from the fact that the members of the Wildfire investigating team were wearing highly reflective visors.

“These curved masks reflected everything in sight within an angle of about 200 degrees,” Kline recalls. “That meant that we not only had to camouflage the camera and crew, but that we were also severely limited as to the kind and amount of lighting that could be used without having it reflected by the visors. We did all of the shooting, both exterior and interior, with six reflectors and four FAY lights. That’s all. For the interiors, we could occasionally bounce a bit of light off a wall by means of reflectors aimed through doorways or windows. We didn't use any hidden quartz lights, or anything like that.”

The Andromeda Strain includes a sequence in which laboratory animals are exposed to the organism and then immediately die. This is a very important sequence in the film, because it demonstrates with frightening reality the lethal nature of the germ. These scenes had to look real, and yet not harm any animals. With the help of Dr. M. W. Blackmore, U.S.C. Chief Veterinarian, a simple, safe and effective system was devised.

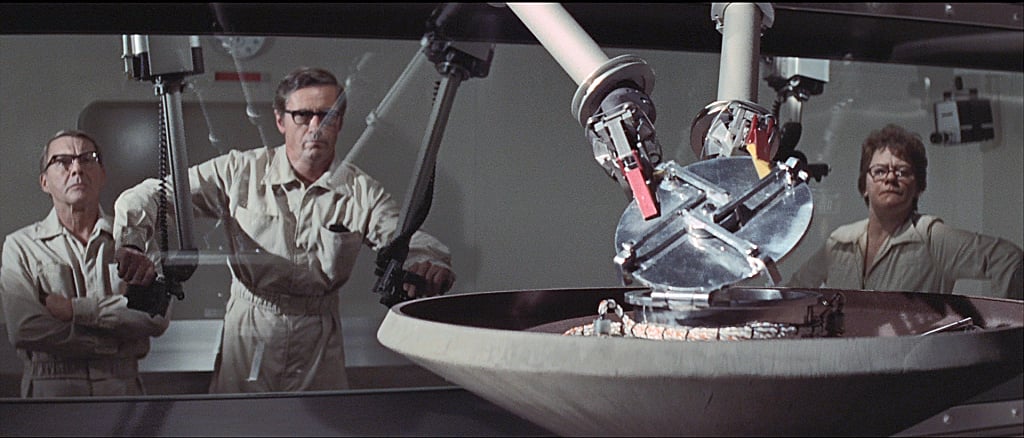

The laboratory sets were divided into “safe” areas and “contaminated” areas. The safe areas were for research personnel; the so-called “hot rooms” were for the infected survivors, plus the contaminated capsule. The two types of rooms were usually separated by means of large plate-glass windows. The hot rooms were made air-tight and then filled with C02 gas. To test the “infectious” nature of the organism, the animals, which were in airtight little cages with oxygen, were lowered into the C02 filled rooms. Then a mechanical hand was used to open the lids of the cages and the invisible C02 gas would rush inside. This sudden change would make the rat or monkey lose consciousness, to be revived seconds later. Just to make certain that no harm was done to the animals, a man wearing a scuba tank was positioned off-camera in the C02-filled hot room and he would grab the unconscious animal and bring it outside the hot room to Dr. Blackmore, who would administer oxygen. Because of these precautions, no harm was done to any animal. A total of two monkeys and three rats were photographed and all recovered perfectly in a matter of minutes. These scenes, which are so powerfully realistic, had to be staged with scientific exactitude and were filmed with two cameras shooting through the glass window.

Laser beams, which had rarely been photographed before, were another special demand of the Andromeda story. In the final scene within the Wildfire central core tower, Dr. Hall is shot at with actual automatic laser beam guns. Ordinarily, the illusion of laser beams would be added to the scene afterward by means of special effects. In the core, Dr. Hall has to scale a ladder while trying to dodge the lasers and out-climb an escaping “poisonous” gas. The laser beams, which can only be seen when they hit a solid object, became visible as they passed through the gas fumes released from the bottom of the core. The green laser beams used in Andromeda were not strong enough to be dangerous, unless looked into directly with the naked eye.

Here again, Kline made tests to ascertain the correct exposure level of the lasers. Once he arrived at the optimum level, he lit the entire huge set at the exposure level which would permit the best photography of the beams. In all these examples, the genuine working devices described in the script were used. This was a key factor in giving Andromeda an air of unimpeachable authenticity.

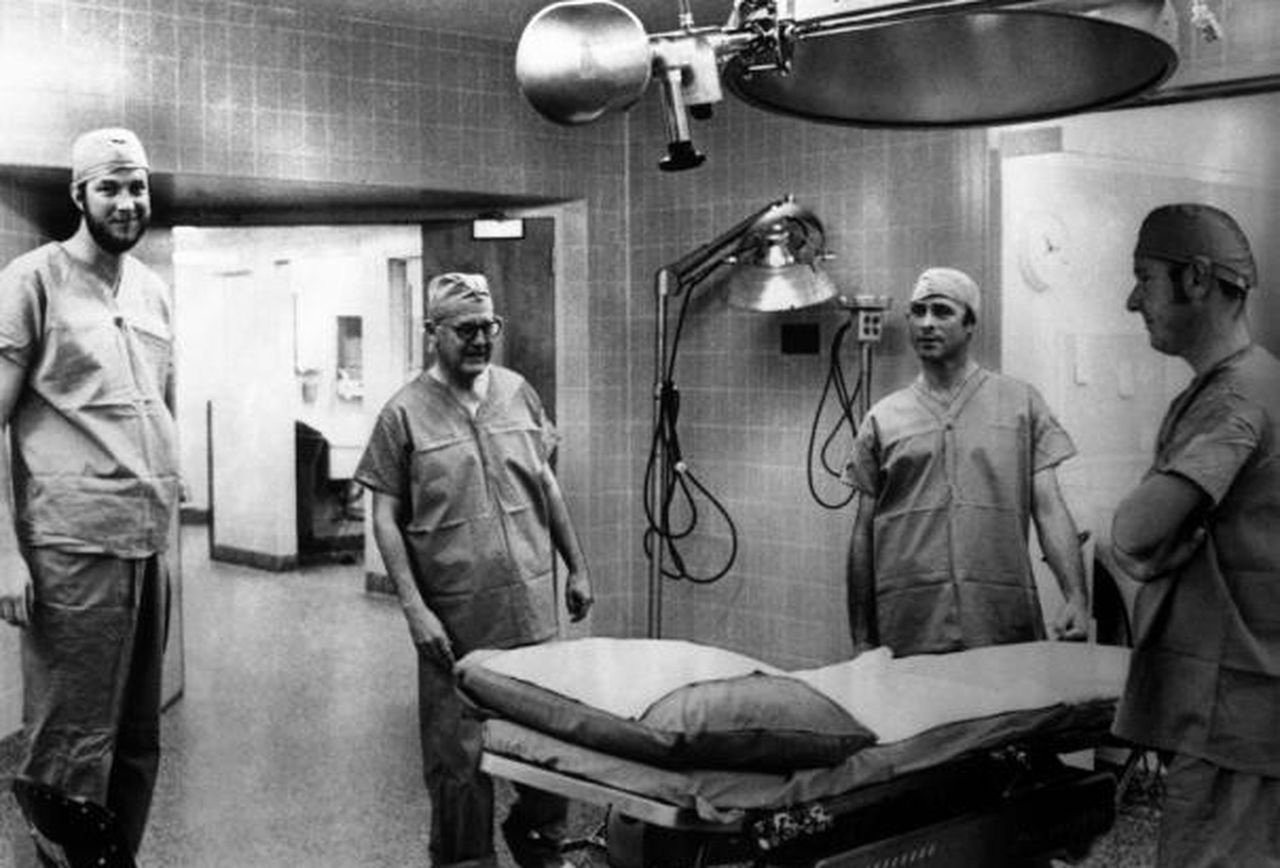

Two key scenes in were filmed away from Universal’s sound stages at authentic locations. Both Dr. Leavitt’s laboratory and Dr. Hall's hospital operating room were filmed on actual locations in Los Angeles.

Dr. Leavitt’s lab sequence was shot in a real Cal Tech research laboratory, though some additional set dressings were installed to satisfy the story. The windows were darkened with black cloth to achieve the effect of night and the window panes were sprayed to simulate frost and snow. The main reason that this sequence was photographed away from the studio was the availability of the very delicate, large and expensive spectrograph, an apparatus which analyzes basic elements of chemical composition. This machine was available only at Cal Tech and so Andromeda went to it.

Similarly, Dr. Hall’s operating room sequence was photographed in an actual operating room at the Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, Calif. It was necessary for all equipment to be scrubbed down with an antiseptic and for all crew members to scrub and wear sterile operating-room garments in order to preserve the room's antisepsis.

Andromeda necessarily dealt with scientific information of a complex nature. Scenarist Gidding (who previously worked with Wise on I Want to Live and The Haunting) developed a radically different script, dubbed a “cinescript,” in order to assist cast and crew in rapid comprehension of highly sophisticated cinematic techniques, many to be used for the first time. The cinescript incorporates such visual aids as illustrations, diagrams, schematics, computerized animation, multi-screen effects and computer printouts.

Kline was frequently photographing live action for inclusion within multi-screen sequences which, in final form, would fill only a portion of the frame. The cinescript was a valuable blueprint, enabling him to quickly understand the complex and specific demands of many sequences.

As the film nears its climax, there is an interesting distortion shot representing Dr. Hall’s point-of-view. The script calls for a composition to simulate the dazed and near-unconscious state of the scientist. Wise and Kline created the effect by using an old CinemaScope lens and reversing the anamorphic optical squeeze during the shot to give the illusion of Hall fainting and losing his equilibrium.

“Robert Wise is the most complete director that I have ever worked with,” said Kline.

Wise said of Kline, “Dick was willing to try new things and experiment and innovate. He realizes the importance of working as a team, in close cooperation with all of the creative members of the production staff. He contributed tremendously.”

Andromeda was a difficult motion picture to make because nothing like it had ever been done before. There were no compromises in any of the technical, highly unpredictable areas. The filming was dependent on many non-theatrical, scientific machines and several other processes and events which, though true to the spirit of the story, were cinematically unknown.

The film’s action unfolds upon the screen at such a pace and with such a smooth flow that the average viewer cannot possibly imagine the vast amount of preparation and work that went into the project, nor gain an idea of its complexity. The skilled direction of Robert Wise, the imaginative cinematography of Richard Kline, ASC, and the devoted efforts of many other top Hollywood technicians all combined to create the spectre of frightening reality that is The Andromeda Strain.

Richard H. Klein went on to shoot features including Soylent Green (1973), King Kong (1976; earning his second Oscar nomination), Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979; also directed by Wise) and Body Heat (1981). He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003.

AC contributor Jon Bloom wrote this piece while still a student at Antioch College in Ohio, which offered a unique co-operative education program that allowed him to spend time in Los Angeles pursuing work in the entertainment field as part of his studies. At the age of 19, one of his first positions was as an assistant to Robert Wise during the production of The Andromeda Strain. He would later assist Robert Altman and then serve as an assistant editor on The Godfather: Part II. In 1980, he founded his own production company, BloomFilm, which would become known for creative theatrical trailers, TV and radio spots and other marketing media. In 1984, the producer-director earned an Academy Award nomination for his short Overnight Sensation. Bloom has also earned six Emmy nominations and won a Clio Award (plus six additional Clio nominations), among other honors. In 2020, Bloom was re-elected to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences Board of Governors. This marks his seventh three-year term representing the Short Films & Feature Animation Branch.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.