Star Trek 50 Part V — Voyage Home Directing

Actor-director Leonard Nimoy describes the intricate production and post of this hit entry in the Trek feature franchise.

The fifth entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise.

The Fourth Trek: Leonard Nimoy Recollects

Leonard Nimoy’s office at Paramount Studios is modest in size and comfortable. Even if his name were not on the door, a quick glance around the quarters would identify the occupant. The outer office is filled with bits of Star Trek memorabilia, poems by Nimoy, pictures of Spock by fans and others – even a small plaque commemorating his current film, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The inner sanctum says a little more about the man. Beautiful photographs of whale flukes grace one wall. Another wall features lobby cards from one of his lesser-known films, an early-fifties serial called Zombies of the Stratosphere. Behind his desk hangs a poster from the one-man show Nimoy wrote, directed and starred in — “Vincent.” Clearly, there is much more to Leonard Nimoy than pointed ears and arched eyebrows.

Nimoy, who is best known and loved as the alien Mr. Spock, exercised more than his acting talent in this, the fourth Star Trek film. He shares credit for the story with Harve Bennett. And for the second time, Nimoy directed his long-time friends and associates as they reprised their roles as the crew of the USS Enterprise. With his second major motion picture in post production, Nimoy spoke confidently and with good humor about his role as director.

“I have been directing for a very long time. I started directing theater in the 1950s and films in the ’70s. I didn’t pursue it simply because I was having too good a time as an actor. I had wanted to direct Star Trek from the time we started doing the series. Bill Shatner and I both did. We were not allowed to. It’s just as simple as that. We were refused the opportunity.

“But the idea of directing is something I have been dealing with for some time, although not prominently. And when Spock died in the end of Star Trek II and the studio started talking about a resurrection — for lack of a better word — they called me and asked if there was anything I would like to do. ‘We would like you to be involved in the making of Star Trek III — meaning that they wanted me to act in the picture. We struck a deal. I said I wanted to direct. The reaction was very good, I must say.” Nimoy laughed, “They put me through the coals later to test my commitment and sincerity.” He added, “I felt that it was time I stopped fooling around with directing and really got serious about it. Stop dabbling and do it. And then I was asked to do Star Trek IV before Star Trek III even opened.”

“I definitely see the cinematographer as a fellow artist. The greater the artist the better I like it."

— Leonard Nimoy

Star Trek IV is important to Nimoy for many reasons. He has been involved with the film from the very beginning; consequently it reflects many of his own planetary concerns and his sense of humor. “I had a lot of input on the story — the story credit line reads story by Leonard Nimoy and Harve Bennett. When they asked me to start on Star Trek IV, Jeff Katzenberg (a Paramount executive who has since moved to Disney Studios) and I talked about who was going to make this picture. I had had some constraints on Star Trek III. He said flat out that they wanted my vision. ‘This is a Leonard Nimoy film.’ That being the case, Harve and I were asked to develop a concept. I went off to Europe to work in The Sun Also Rises. While I was there, I also wrote a seven- or eight-page outline of what I thought the film could be about. Harve came over and we collaborated on the material... it went in as the very first concept.”

As the initial concept developed, Nimoy got involved in some tantalizing research and some frightening philosophical questions. “When we started out to do this project, I went to three universities — the University of California, Santa Cruz, Harvard and MIT — to talk to three different professors who are physicists, scientists and futurists. I spent several hours talking with the professors about their immediate concerns for the future of the planet. We talked about their ideas for potential contact with extraterrestrials. What it might be like. Where it might come from. How it might come. How we would deal with it. The philosophy of it. And the immediate impact on the sociology of the planet, the religions of the planet. I had some great times.

“Then I was also in touch with Edward O. Wilson. In his book Biophilia he tells us that in the 1990s we could be losing as many as 10,000 species off this planet per year — many of them having gone unrecorded. We won’t even have known what they were and they will be gone. He touches on the concept of a keystone species. If you set up a house of cards you may be able to pull away one card successfully . . . and another card successfully. But as some point you are going to get to a card that is a keystone card. When that one is pulled away the whole thing will collapse. The same might be true of species: a planetary imbalance might be caused by the destruction or loss of just one.

“Also, I came away with the concern amongst these brilliant people that science is expected to quickly find solutions for the stupidity — or arrogance or lack of conscience or call it what you will — of the rest of society. Our tendency is to say, ‘Here’s this pressure group pestering us — but things aren’t really bad yet. Let’s pay attention to the things that we really have to.’ But when the ozone question or the species question or whatever gets really bad we’ll turn to scientists and say, ‘Okay, here’s the money, goddamnit. Fix it!’ They, at some point, may have to come back and say, ‘It’s too late. We cannot do that anymore, there was a time when we might have...’

“There is a fantasy that if we did have a holocaust kind of war on this planet, those who are left could eventually rebuild the planet. It’s simply not true. They could never again reach the technical accomplishments that we have reached today. There was a time when you drilled oil only when you saw it oozing out of the ground. Your equipment could be pretty crude. Now we need enormously sophisticated equipment to drill several hundred feet in the ground where it is suspected that there is oil. You wouldn’t have the technology to do that anymore because you need the oil in the first place to make that kind of equipment. In a sense, we are burning bridges behind us.”

Nimoy was not about to miss an opportunity to address these concerns on some level. “I became hopeful that we might be able to incorporate some of these ideas into the picture. I think that I have been successful in creating a fun picture. My idea was to make the philosophy the kind of stuff that lingers with you, that is revealed to you later. You think, ‘Was there something going on in that movie while I was sitting there enjoying myself? Could this possibly happen?’ This is not a China Syndrome, in other words, where the problem is what the picture is about.” Nimoy hesitated, “...It is and it isn’t. It’s handled in an entirely different way.”

Star Trek IV clearly has a serious side. But there is another side, too. No director can make a film in a vacuum. There are many things that must be considered, but Nimoy was confronted by an unprecedented dilemma. How many television shows have been developed into money-making, award-winning features? Not just one, but three. With the same cast. With 20 years of fans. With over 70 story lines that have already been developed. In other words, how could a director possibly come up with something original, but true to its origins? Nimoy no doubt called upon all his resources, plus those of his alter ego Spock, to come up with a new approach for a Star Trek movie. This one takes place primarily in contemporary San Francisco and it’s funny.

“What we have set out to do, frankly, is very dangerous. I was trying to serve a lot of masters. I wanted to continue and wrap up some threads that were left over from Star Trek III. At the same time I wanted to make an entirely different kind of film. Those ideas seemed in opposition to each other, but I think we pulled it off. At the same time, I wanted to make a film that would be accessible and enjoyable to people who had not seen Star Trek III. I hate to think that people would think that they have to have seen Star Trek III in order to enjoy this picture. I think we’re okay on that. I also wanted to make it accessible to people who don’t go to Star Trek movies. I wanted to make it a movie movie.”

To open up the possibilities for a “movie movie,” much of the film was shot on locations in the San Francisco area. It starts out in space — on Vulcan, right where the last one left off. Through a familiar science fiction device, our voyagers soon find themselves on the good old terra firma of the 1980s. “In the past, we have been confined to sound stages with Star Trek. Numbers I, II and III were all shot primarily on sound stages,” explained Nimoy. “This one is different in setting and in tone. Star Trek IV starts out like a Star Trek movie and then it makes a left turn. It is intentionally very different. I felt very strongly about the fact that II and III were really of a kind. They both were played with black-hat heavies. We are the good guys and they are the bad guys and we have to beat them. I really wanted to make a change in that this time.”

Nimoy was quick to point out that he had not forgotten the fans. They are a force that must be reckoned with if one makes Star Trek movies. “I don’t want to give any impression that we are turning our back on the fans or are leaving them behind at all. Quite the contrary, I think they are going to eat this up! One of the things that Star Trek fans always enjoyed a lot about the series was the humor. There was always something tongue-in-cheek if not flat-out comedy. There was always some wry look, a line, an eyebrow raised, something that let them in on the joke. On Star Trek I it was forbidden. I mean it was forbidden! It was decided that we were doing a serious motion picture here, we would not do funny stuff.

“I’ll give you an example. Star Trek I — which filmed for six months — was really a trial for the actors because we were not very much in it at all. We were, much of the time, looking off camera at things that would later be done by Doug Trumbull or his crew. We were looking in wonderment and awe and saying things like, ‘What do you think it is?’

“‘I don’t know.’

“‘What do you think it is going to do next?’

“‘I don’t know!’

“Very exciting stuff. At the end, in fact it was the last day of filming, we were shooting the tag scene on the bridge. The adventure is over. The world has been saved. Everybody is safe. Kirk had brought together this crew after an 11-year hiatus for this one special mission. He had taken McCoy out of retirement, called Spock off of Vulcan. Now it is time to take everybody back. He says to McCoy, ‘I can have you back on Earth in two days.’

“McCoy says, ‘Now that I’m here I might as well stay.’

“Then he says to Spock, ‘I suppose you want to go back to Vulcan.’

“Spock’s line, as written, was ‘My business there is finished.’

“Final rehearsal before the take, Kirk says, ‘I can have you back on Earth...’ McCoy says, ‘No, I’ll stay here...’ and he says, ‘I suppose you’ll want to go back to Vulcan.’ And I said, ‘If Dr. McCoy is to remain on board, then my presence here will be essential.’

“Everybody roared — which I knew they would. But then I saw the command group gather... They really huddled. Bob Wise came to me and he said, ‘Seems inappropriate to be doing humor at this point.’ I said, ‘I offer it to you. I can’t make you take it.’ They wouldn’t let me do it. They were really adamant about it. That picture had a very classy look. But it was not a lot of fun – either to do or to watch. There were touches of humor in Star Trek II and III. This picture has more humor in it than all three put together. And it is intentional. It is flat-out fun.”

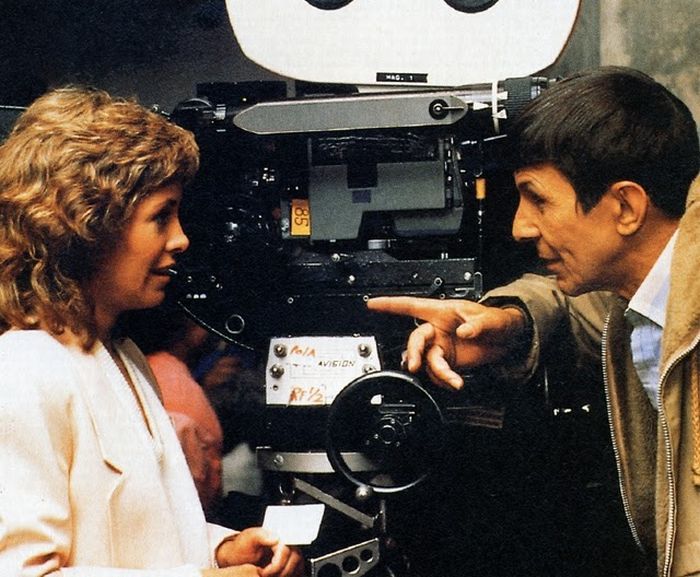

To bring his vision to the screen, Nimoy chose Don Peterman, ASC as director of photography. When asked about his relationship to and expectations of the cinematographer, Nimoy commented: “I definitely see the cinematographer as a fellow artist. The greater the artist the better I like it. Major contributions are possible and minimal contributions are harmful. I want the picture to have a certain look — a look we agree upon and that I feel he is capable of delivering and is committed to. I try as much as possible to give him time and authority to do that. Finally, at the end of a given period of time, I must evaluate whether or not the time that he is taking is being validated by the work that he is producing. I may feel that I would really like 12 set-ups today, but if he can only give me nine, I’ll find a way to do without — maybe combine the other three — if the nine are exemplary. That is very important.”

Nimoy continued, “I want him to know what I want thematically, what the central emotions are. I might say to him, ‘This is a fun scene. I don’t want moody lighting. I don’t want the audience searching for the characters and wondering what the psychological undertones are. This is flat-out fun. This is farce or this is poetic.’ Or, ‘This is dangerous. When he walks into the room, I want everybody to be scared.’ I want to communicate emotional ideas to him and I want to have confidence that he will deliver them.”

Peterman was chosen by Nimoy for very specific reasons. “Don Peterman shoots from an idea, I think. I saw stuff that he did that tells me somebody has been paying attention, there is tone; it’s not just, ‘Light it and get an image.’ The image has to come from the cinematographer. The director can’t do it... unless the director is a cinematographer. I happen to be a photographer, so I can look at a set and get some idea of what he is doing. But it is not my responsibility to tell him where to put the key lights or to backlight or frontlight or sidelight a character. It’s his responsibility. I can help him do that. If I want a scene shadowy and scary and he says, ‘Okay, if I can have a light source down here on the floor...’ I say, ‘Fine, I’ll have a character that knocks a lamp onto the floor.’ Then you’ve got your light the way you want it. I’ll help to provide him with tools to work with. He has to articulate it and take responsibility for the image.”

Nimoy has commented in the past that the first Star Trek movie was too dependent on special effects. He summed up the attitude of the producers of that first film as “Well, now that we have the budget to do all the effects that were denied to us on the television show, shouldn’t we do a lot of them?” But he also realized that it was practically impossible to make a Star Trek movie without special effects. With this in mind, Nimoy has tried to keep the effects in their proper place. “The spaceships are minor characters in this film. In spite of the fact that we spend a lot of time on one, it is not about the ship.” Nonetheless, he is pleased with the effects that do appear. “In addition to work done at ILM, there is a lot of brilliant physical effects work done by Michael Lantieri and his crew. We pulled off some very tough stuff technically during the shoot and came in three or four days under schedule.”

Special optical effects put a certain artistic burden on the director. Work can begin on the effects before a movie is cast. Everything is planned down to the smallest detail; but optical effects don’t usually come together until after the live action is complete. To maintain continuity and consistency in what finally appears on screen, the director must establish a common language with effects specialists early on. Nimoy explained his approach: “We start out with an exchange of ideas between me and the people at ILM. We use very specific drawings so that everyone is talking about the same image. I don’t necessarily storyboard the whole film, but all of the special effects are storyboarded. Some other scenes will be storyboarded if there are some special requirements.”

Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that what seems to work well in the storyboards will look as good on film. “Those images change as time goes on,” said Nimoy. “They are changing today — for various reasons. The storyboards are built on preconceived ideas of the images that go before them, the images that go after them, the length of time that that image will be on the screen and how much of the story to tell with it. Now, I have cut the picture long before those elements start to arrive. I’ll do my cut and I will say to myself that the picture is working. Then along comes one of those elements and I think, ‘This is jarring when it goes into that slot.’ It may be jarring in a good way or it may be jarring in a bad way. If it is jarring in a bad way, I may say to them, ‘Hey, I need something different.’ Or, ‘This is not what we agreed on. This ship isn’t flying fast enough or it should be coming from the top of the screen or it should look like it’s climbing instead of falling...’ Whatever. It may be something that has to be done again.

“On the other hand, I may see something come down from ILM that I love. I might have to make some adjustments to what comes before or after it because I want to keep all of what they have delivered. I want to make it work.

“Everything constantly changes. In the editing I may find that a shot we have contracted for and that is going to cost me 20 or 30 or 40 thousand dollars is no longer necessary. It happens. On the other hand, I may find a shot that we had not planned on that would be helpful. There is a constant adjustment in the accounting that goes on.” Nimoy paused and then laughed, “It is much easier to drive the price up than it is to drive the price down!”

He continued, “This kind of give and take has to go on right down to the final, final cut. I’m never sure how the film is going to look until it’s finished... not really. I may have a vision in my head of how I want it to look, and if I am lucky the ILM art director has the same vision. And if we are lucky as a team, his people deliver it looking exactly the right way. It can be an exciting process because they are very talented people at ILM.

“We have gone through some turmoil on this picture and I am not going to lie to you, but I really think we are coming out of the other side very well. I go for the ideal and I don’t think I will have to compromise.”

In spite of the diversity of cinematic problems, for Nimoy the greatest challenge was “to let the people in the film have fun that is palpable, fun that you can feel and see. On Star Trek III, I approached the film entirely differently. I may have been wrong; I may have been right. I felt that film was really about camaraderie. It was about commitment to friendship and loyalty amongst a band of people. During the course of the designing and framing of it, I kept saying to Charlie Correll, who filmed it, that I wanted it operatic. I wanted fire, storm, great passions! This is not just about life, it’s about commitment, personal need and demands! Dick Shickel in Time magazine said, among other things, that it was the first space opera really worthy of the name. I was so happy to see that, because I had really been talking Wagner — sturm und drang.

“The Voyage Home is entirely a different kind of movie. We have some pretty grim stuff to deal with because the threat is there. But ultimately, I wanted the people to have fun. There is a lot more of all the regular character in this and we have a wonderful performance from Catherine Hicks. Jane Wyatt is back for the first time since the series as Spock’s mother. John Schuck plays a Klingon ambassador.

“I have been around a long time. I have been on sound stages since 1950,” admitted Nimoy, who turned 55 in March. “But I never dreamed I would find myself directing a $22 or $24 million big, physical picture like this... and feeling totally comfortable, not awed by it at all. None of it scares me. I’ve seen it all done before, or I know a way can be found to do it if you get the right people.”

You'll find our complete story with cinematographer Don Peterman, ASC here.