Star Trek 50 Part VI — Voyage Home Cinematography

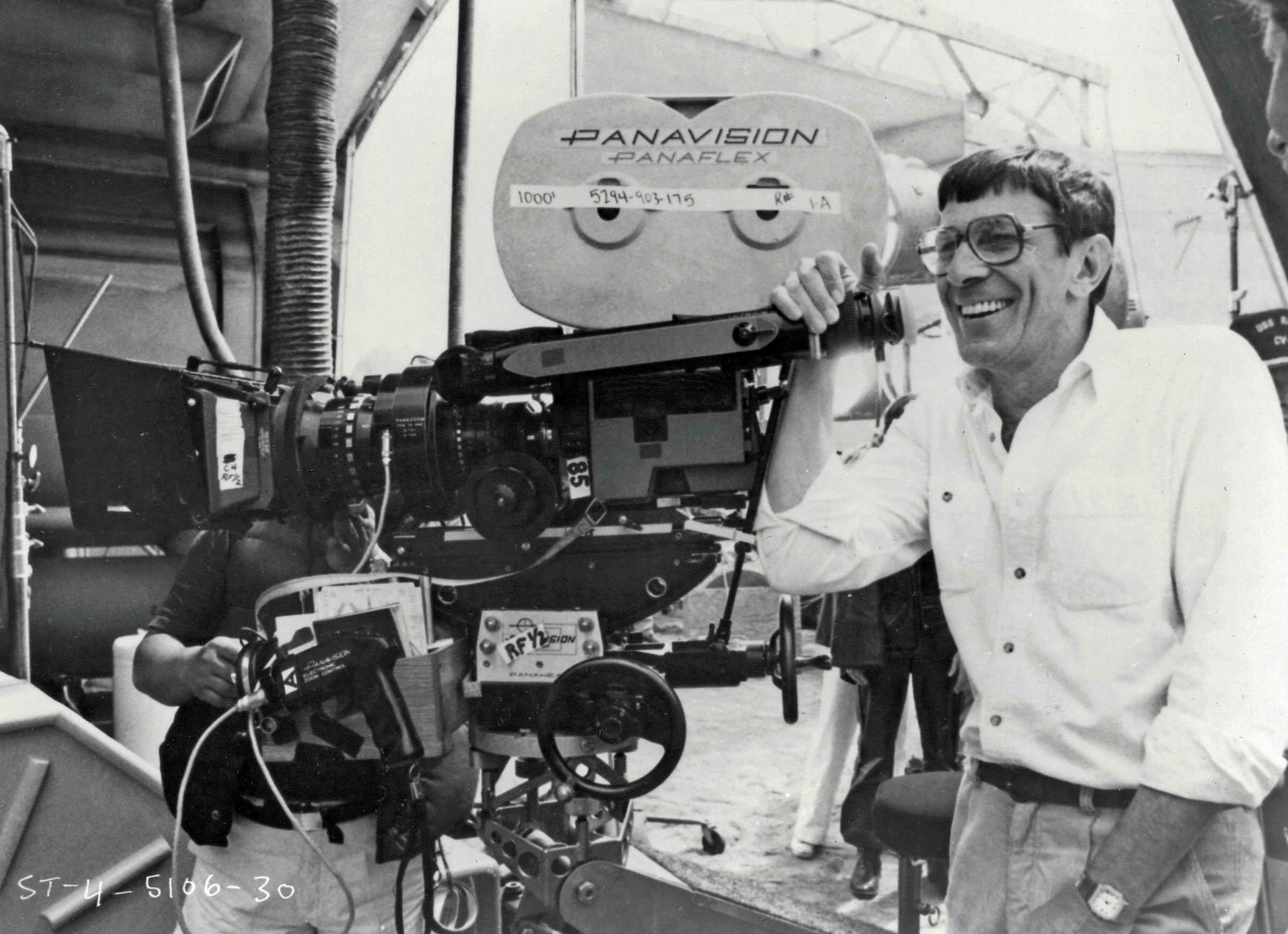

Don Peterman, ASC details working with director-star Leonard Nimoy on this smash hit entry in the Trek feature film series.

The sixth entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise.

The Fourth Trek: Don Peterman on Earth

“Leonard Nimoy wanted to make this movie altogether unlike any Star Trek that had gone before. When I went in for an interview, he said, ‘I want to make this really, really different, because it isn’t about a war out in space. I want to change the look of it because they’re coming back to 1985.’”

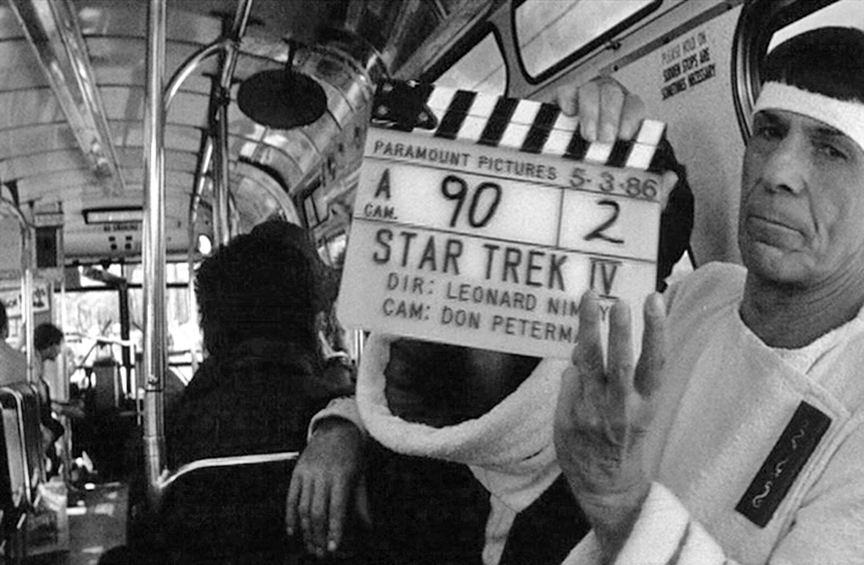

Don Peterman, ASC went on to say that his interview with director/actor Nimoy resulted in one of his most unusual and interesting assignments — as director of photography of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Paramount’s $23 million episode in the popular interplanetary saga which began 20 years ago as a television series. Even without “wars out in space” the new adventure reaches the big screen as a spectacular entertainment to dazzle the eye, but it is — literally — more down to earth than its predecessors. It was produced on the Paramount lot and on location in San Francisco, San Diego and other coastal areas. While production was underway, Peterman said that principal photography was scheduled for 55 days “and we finished three days early.”

“There were a lot of days inside the Klingon spaceship.” (In Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the traditional starship under Captain Kirk’s command, the U.S.S. Enterprise, was destroyed and the crew escaped in the Bird of Prey, a warship belonging to their enemies, the Klingons.) “It’s actually a different kind of ship than was used in III, where they built only a small part of it. They built a new ship and completely redesigned it because you didn’t see enough of it in III to really know what it was like. Jack Collis, the production designer, and I were determined to make it low ceilinged and realistic, like an old freighter type of ship. He painted it in an olive drab and brown inside and kept it in a monotone of warm tones. All the readouts were put in in red and amber and it has a few white lights, but we didn’t have a wide mixture of colors and there are no cool colors in it.”

“I light by eye and then hope it’s enough.”

— Don Peterman, ASC

Peterman, who won acclaim for his distinctive lighting in such unusual pictures as Flashdance and Cocoon, is said to direct light sparingly. “I use more bounce light — I bounce light into cards and let it come back through paper,” he confirmed. “Inside the spaceship there were consoles — Spock and Doc sat at one and Shatner at another and two people at each of the other two. These were like control boards, so I put milk glass where the panels would be and lit them very softly. It wasn’t like flashlights shooting up, it looked as though the light was coming off the panels. I put some 3200°K lights in there and put them on dimmers. We also had a big console board made out of glass and plastic. I put lights underneath and shined them up into white cards that bounced the light through the glass.

“In that ship they have a lot of light changes. They go around the sun to get back to 1985, a time warp, so as they got closer to the sun we shook everything and then it went into a warning mode and it got very hot and yellow. We had all these light changes going on in each take, in close-ups and everything else. It went from normal to shaking, to red, and finally the whole ship is about two stops overexposed within a yellow light. We put a lot of smoke into every shot. We shot about 15 days in there, so we tried to keep the smoke consistent. At first all the actors were cold to the idea, but then Shatner realized that it needed that look. Most of their ship scenes in the past were aboard the Enterprise, which was very clean, but the smoke and dirty look worked for the Klingon ship.”

The indirect lighting technique proved useful in photographing the actors who have been essential to the series for two decades, as well as a gorgeous new leading lady, Catherine Hicks. “Most everything in there was soft, ambient light, with no big keylight, so it worked out pretty well for Catherine,” Peterman explained. “Remember, I’ve got actors in here who are in their 50s and I’m trying to make them look 30, so it worked for them, too. When I did a close-up of her I did it more the way I’ve shot cosmetic commercials, using a lot of double-soft lights. But I didn’t compromise very much between her and the men. I lit DeForest Kelley about the same, with soft light and no big source.”

The old Enterprise set on Stage 9 appears briefly at the beginning of the picture. It represents the sister ship to the Enterprise. After these scenes were completed, half of the set was redone to represent the New Enterprise, which appears at the climax of the show. “After everything has happened and they save the world, Kirk and his crew get their new ship and they see that the ship that blew up in III has been reconditioned,” Peterman said. “We only have one scene in the New Enterprise, where they go inside and then take off. We shot it to look very clean. The ship has been changed: it’s now white and has stainless steel struts. We did all the read-outs in blue and green — the very opposite of the Bird of Prey. It’s very high-tech, crisp, with no diffusion and no smoke.”

Another impressive Voyage Home set is the control area, which includes three large process screens. “It’s nothing as elaborate as what Bill Fraker [ASC] did on War Games,” Peterman noted. “All our process plates were put onto video and they broke them up so that the image was fading, because the earth was supposedly being surrounded by clouds which interrupted transmission. We shot the three screens with people in front of them and had no trouble with any of them. Of course we had Bill Hansard and his brother, Don, working with us almost all the time.” The Hansard brothers are experts in projection process work. “We had perfect exposures on those screens and everything worked out great.

“We have some scenes with screens and some big windows. It’s supposed to be on a hill overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge. When we shot toward the windows we used a blue backing and Industrial Light and Magic, the Lucasfilm visual effects facility in Northern California, put a futuristic city out there with the Golden Gate Bridge. There’s a big console in the middle, and the whole table was bottom lit with just white milk glass on top, so that the people standing around are all lit from it, and then from the screens. When the lights went out it was great. The screens had what we call snow now, but for 300 years from now we made it different, with long lines in black, white and gray running across. We silhouetted the players against them, with the only light being just the screens and people panicking in front of them in silhouette. It’s one of my favorite shots.”

“Star Trek always was filmed mostly on a stage before and they could never use long lenses because it’s impossible to get back far enough. We tried to make it a little different by using really long lenses as much as we could, 500mm and 1000mm."

Another matte shot which was composited by ILM was described by Peterman: “Down inside the space ship at the bottom level is a storage area. Scotty is in charge of that and he went down and supposedly emptied it of all the stuff that was stored. Then they put glass up and beamed the two whales into this area of the ship. That’s a bluescreen shot, and we now have a matte shot from ILM in which our actors are standing there and the whales are floating in the tank right behind them. These are miniature whales which were photographed at ILM. “We had a set built for the trial when the crew returns from its adventures in III. To save money, we double-ended the set. At one end there’s a big screen and the president of the federation is up high and there are rows of seats along the side. The Klingon ambassador is down on the floor. I put a pool of light — a real hot HMI — shooting straight down. I put the Klingon in that.”

The “double-ended” set made it possible to make the reverse angle shots without having to build a gigantic set. The set was built to only half of its actual length but both end walls were constructed, one being the front which includes a large process screen, the other being the back, which includes a door. Peterman described the ingenious method used in making the set appear twice as long: “When we had to shoot toward the doorway, we moved the pool of light and put it on the back wall and doorway where the front had been. Then we flipped the people in the seats around and put them on the opposite sides. It was like getting both halves of the place for the price of one. It looks big and the set only cost about $65,000.”

The unusual lighting used on the courtroom set created an aura of mystery well-suited to the delegates, who are somewhat reminiscent of the intergalactic spacemen in the canteen sequence of the first Star Wars picture. “The courtroom was full of strange aliens because the federation is made up of people from all the different planets,” Peterman pointed out. “The fluorescent lights under the milk glass counters made a glow, and I had some little desk lights. I didn’t use any studio lights in there; we put a big muslin over the top and I think I had six chicken coops up there and I took them way down low on the dimmer. Once in a while, if we had some dialogue, I’d use a bounce light card. Overall we worked with very low light, maybe 15 footcandles.”

Some of the most unusual work done at the studio for Voyage Home involved the big surface tank on the front lot. This is a shallow tank which was designed many years ago for the staging of miniature ship action. It originally lay behind the Western town set, which was torn down several years ago to become a parking lot. The tank, which I depressed four feet, is now part of the parking area when it isn’t being used for filming. The IV company built a bridge which runs through the middle of the full length of the tank. Parallels of varying heights were set up in and around the water for the deployment of wind machines, lighting arc devices, camera platforms and overhead diffusion materials. A huge taffeta sheet was stretched on cables high over the entire tank, with wide strips of black, opaque plastic material positioned on the overheads so they could be drawn like curtains over the taffeta. The cables were moored at the ends of the tank by large “bull” spikes driven into asphalt. Near the middle of the tank, a 20 x 40-foot pit descended 12 feet below the floor and housed some underwater sets. Tracks were laid from one end of the tank to the other to accommodate the movements of two manmade whales.

“We put up that gigantic taffeta because these scenes occur during a storm, so I tried to knock the light down as much as I could,” Peterman explained. “I felt that if I put black up there it would get too dark. We had a little trouble with the lightning reading well, I would have liked a little more, but exposure gets so high in the daytime, even through the taffeta. We shot all day, but I tried to do most of it at times when the lightning would show up best.

“My plan was to put up the taffeta so I could get light through it if I wanted to, then run strips of black down the cloth and have grips stationed on each end of the parallels to put them on or take them off as necessary. We put on four of them and got the exposure down pretty low. It had the feeling of overcast that I wanted. We put a special gray backing over the old blue sky backing and when we put smoke in front of that it looked deep. You never really see the backing, but it was there in case there was a hole in the smoke. I used 20mm and 24mm lenses to give it depth and stayed on that backing in case the smoke didn’t cover it.

“We had a whale going by, we had the big tail that came out and splashed down, and there’s another shot where the whale comes through and a fin goes up. We had gas wind machines; it has to be gas, the electric ones just aren’t enough for a job this size. We had five of those and we blew water into one of them and smoke into another. We had three water pumpers which chopped the ‘sea’ up pretty well. You’ll be amazed when you see that footage. It was all in the tank and you’d swear to God it’s a hundred square yards of ocean.”

“Our full-size whales were put on a track which started at one end of the tank, went under the water and went over humps here and there and down through the pit and on to the other end. One was a tail section, and as it would go along under water it would surface, then the flukes would come up in the air, then it would go under and come up again farther on.”

AC was at the scene when the storm was staged and can add that even with all the equipment and a small army of crewmen surrounding it, the Paramount storm at sea was enormously impressive. The effect was not achieved without difficulty. “About the biggest problem we had out there was the wind,” Peterman revealed. “When we turned the wind machines on, they lifted that taffeta up like a sail or a parachute. It put pressure on the parallel and pulled those ‘bull’ spikes that were holding the cables, about 20 of them, right out of the asphalt. It ripped the cloth down one side and everything was about to go into the tank. That taffeta alone is worth $5,000. We had to resew it.

“There was an underwater set that Jack Cooperman [ASC] shot for us. That pit is only 20 x 40 and because of the budget they wouldn’t make it bigger. It has been there a long time and they just dug it out — it hadn’t been used in years.”

Peterman made it clear that one doesn’t photograph real humpback whales cavorting in four feet of fresh water. The full-scale whales were constructed on the lot under the supervision of Mike Lantieri, a young mechanical effects expert. Other whales were built in miniature at Industrial Light and Magic. “Our full-size whales were put on a track which started at one end of the tank, went under the water and went over humps here and there and down through the pit and on to the other end. One was a tail section, and as it would go along under water it would surface, then the flukes would come up in the air, then it would go under and come up again farther on. The tail was eight feet across. It was pulled by power winches and we could run it in either direction. We had another which was the side of the whale with a fin on it, and at one point the fin went up and then down again, like it was saying goodbye to the guys. It was 30 feet long. The tail of the other whale was eight feet across. During the storm this giant tail goes up in the foreground and then splashes. It looks great. There’s a little bit of a jerk in it when it’s going down in the take that Leonard liked, but not very bad. I was really impressed at the way those guys did that. Mike Lantieri deserves a lot of credit. He worked with me on Flashdance, too; he really knows what he is doing.”

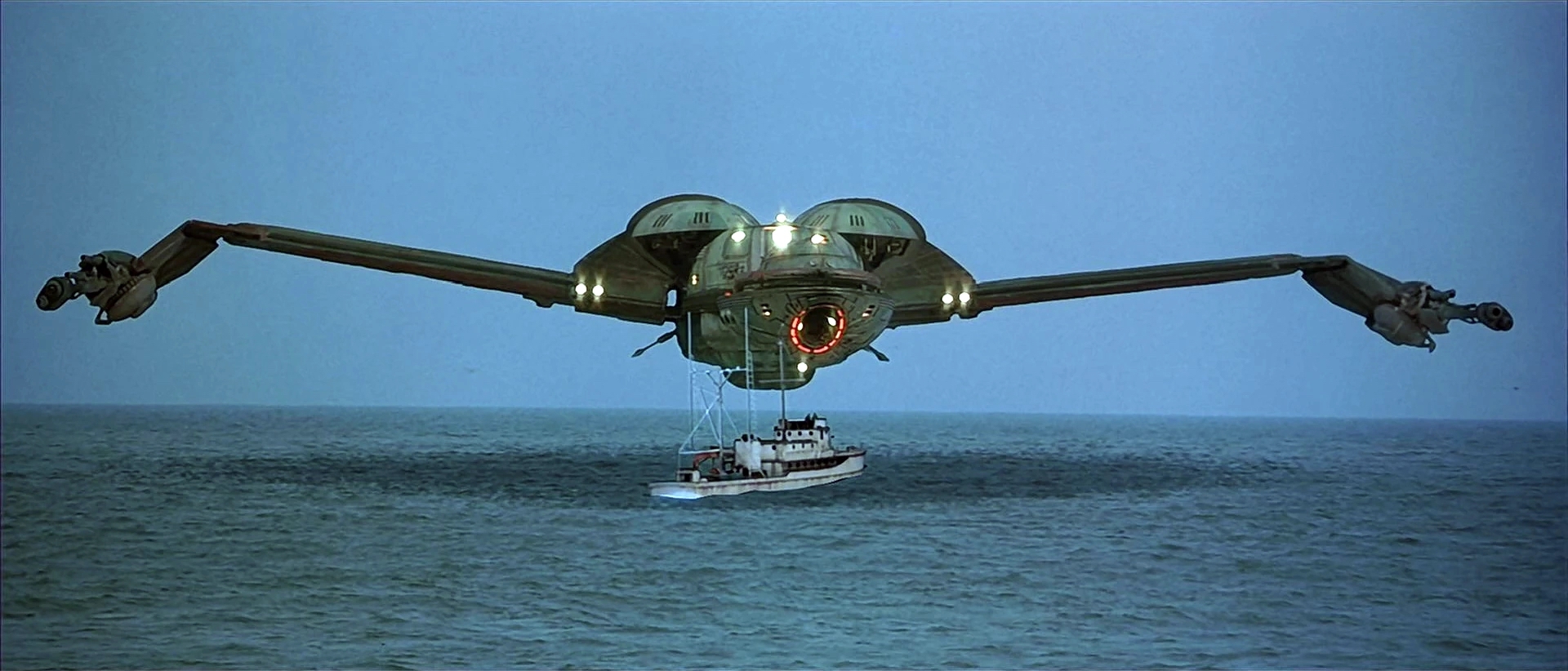

Two whales were sent to San Francisco to be photographed by a second unit for the ending of the picture. “The ship is supposed to have crashed under the Golden Gate Bridge,” Peterman noted. “We towed them out to sea and photographed them from behind as they went out toward the bridge, like they were going home.”

In order to enter a time warp and go into the past, Kirk and company must go out around the sun and return to earth. They land in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco at night and learn that they’re in 1985 AD. The landing sequence, for the sake of convenience, was actually shot on the polo field at Will Rogers State Park in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“It’s a big field and it has eucalyptus trees all around it,” Peterman recalled. “I took light — 10Ks — down on the lower road and shot them back on an angle through the trees. I was very lucky; the fog came in and created shafts of light — it was really kind of eerie. It moved in every night but one that I shot there. Then I had to put smoke in, but it wasn’t as big a shot as the others. This huge thing lands right in the middle of the park, but you never see it. Remember how they could cloak the Klingon ship in III and make it disappear? In IV they cloak it out before it lands — actually to save on production costs — so you just see an imprint of the big thing sinking the grass down, which is a special effect. We shot that with a B unit over at the side: a big imprint of this foot in miniature crushes the grass down. That’s the way we landed it. A truck comes up and stops in a driveway and there’s some dialogue, the two trash men look around and a gigantic wind comes up and the ramp comes down and the passengers walk out onto the ramp. You can’t see the ship, but you can see them and the ramp because they’re not cloaked.”

“People would be walking by and hear Shatner yelling, ‘God damn you!’ and that created quite a stir!”

Much of the San Francisco action really was photographed in San Francisco, where the unique local color of the city provides the background for some highly amusing situations for the visitors from the future, who know next to nothing about Twentieth Century life. These sequences in particular are a sharp departure from previous Star Trek yarns. Peterman described his efforts to give these scenes an atmosphere unlike that associated with the other voyages: “Star Trek always was filmed mostly on a stage before and they could never use long lenses because it’s impossible to get back far enough. We tried to make it a little different by using really long lenses as much as we could, 500mm and 1000mm lenses. That way we could stack the city up and make it a design. I did use the 50-to-500mm zoom up in the city as a long lens because when you’re working in traffic and it’s uncontrolled, it’s nice if you can squeeze the zoom a little bit instead of having to move the camera. We tried to stay away from all the cliché places. We used the bridge, because that’s part of establishing the story, and when we shot downtown we showed part of the TransAmerica Building, but we didn’t go to Fisherman’s Wharf or Coit’s Tower — we stayed around the gritty parts of the city.

“It was interesting, walking around the streets of San Francisco, in the middle of the city, with those outfits on. We had a scene where Shatner goes across the street and a cab comes around the corner and somebody yells something like, ‘Get outta the way, you dumb ass,’ and Shatner turns and says, ‘Double dumb ass on you!’ They don’t know anything about cursing in the 23rd Century and pretty soon they all start cursing. People would be walking by and hear Shatner yelling, ‘God damn you!’ and that created quite a stir!

“Another funny thing was when they’d see Leonard, all dressed in his robes and with his ears on, behind the camera directing the cast — and then he’d step into the scene. It’s okay when Robert Redford does it, because he looks like a normal guy; but when you have a guy with long, pointed ears it’s different. The most interesting thing about it is that we finally got the Star Trek stars out on location.

“We had another unit in Hawaii, right off Maui, photographing live whales,” Peterman said. “There’s a man and his wife there who have a license to allow photography of humpback whales. You have to have a license to get your boat close to them because of the possibility you’re going to ram into one or scare them. So we cut above the water and see these shots.

“We also shot in San Diego for a while on the U.S.S. Ranger, the same aircraft carrier that was used in Top Gun. They even go down in a nuclear sub.”

There was more action with man-made whales in a large, deep tank at McDonnell-Douglas in Huntington Beach. This is the tank in which astronauts are trained to live under zero-gravity conditions. The story has the group from the 23rd Century go to San Francisco looking for whales and they learn that there are two humpback whales in the aquarium at Monterey. They go there and join the guided tour. Actual scenes made at Monterey are intercut with ILM composites and scenes made in the NASA tank at Huntington Beach. The sequence is filled with shot of whales, but as Peterman pointed out, “There are no real whales — they were built by the special effects department out of Styrofoam, 30 feet long, and they move.”

Star Trek IV was photographed in anamorphic format for wide screen presentation. Not all cinematographers are fond of working in anamorphic, but Peterman declared that he enjoys it. “I did Gung Ho! in anamorphic; that was just a comedy, but we had cars on an assembly line and so we figured the format would work well. And in American Flyer we had all those bicycles running across the screen, which means you can get more of them in the scene and you don’t need the headroom. I don’t mind anamorphic unless I have to work at too low a light level; if you work at 1.4 or something like that you have focus trouble, but I find that if you stop down to about 2.5 or 2.8 the lenses are fine. I think I have only one soft shot in all of IV, out of maybe 1,300 shots or so. When there is trouble it is mostly with the wider lenses. A four-inch is no problem, but when you use, say, 33mm or 40mm anamorphic is about like a 23mm. I find that if I shoot those wide open, they start to drift at the sides.”

Peterman said he made little effort to maintain the same aperture from scene to scene. “I light by eye and then hope it’s enough,” he declared. “I try to stay at anywhere from 2.5 to 3.2 inside because of the focus, but don’t like to get much higher than that because the light is traveling farther and making shadows that don’t come from the true source. For interiors I used all prime anamorphic lenses and didn’t use a zoom at all except outside as a long lens once in a while. I used a lot of wide angle lenses inside, like a 24mm, and then I’d shoot the close-ups with a 100mm or 150mm. We used all Eastman 5292 negative on the interiors and on our one night exterior. For outside day scenes I used 5247.”

No snorkels, Louma Crane, Panaglide or other sophisticated equipment was employed in IV. There is considerable dollying in many scenes. Some of the moves were done on a deceptively simple piece of equipment which Peterman finds to be exceptionally versatile: a wheelchair of his own design. “It’s a specially made wheelchair by the man who makes them for the paraplegic basketball teams. I had one of these made up of very light aluminum and we have quick-mount change of wheels. We have a rough tire for working in skid areas and we have a smooth tire. We can put those on right away. It has a seat in it and it has a place where you can stand. I use it all the time. I put an operator in there and, hand-holding the camera, he can even make a boom up. We can make it dolly on anything. Instead of laying track on a sidewalk we use this thing. Also, you can put the camera close to the ground if you’re following feet or something like that. We used it in Cocoon on the deck of the boat.”

At the time he talked to AC, Peterman hadn’t seen many of the finished effects from ILM. “You can’t tell much about the final look of the picture till we get all the ILM parts in,” he said. “That makes it work.”

You'll find our complete story with actor-director Leonard Nimoy here.