Star Trek 50 Part X — Enterprise Goes Back to the Future

Director of photography Marvin V. Rush, ASC explores the early adventures of Starfleet in the new Star Trek series Enterprise.

The tenth entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise.

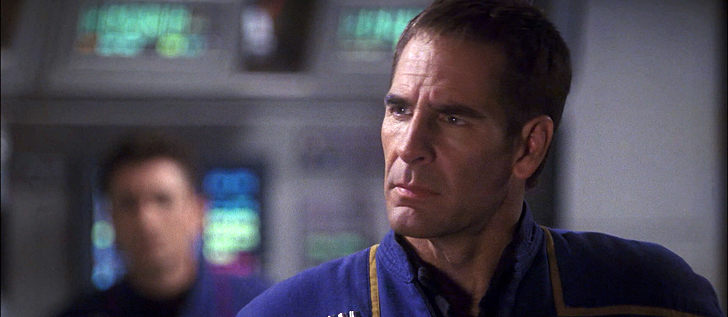

Zipped up in a basic jumpsuit with only the outlines of thin gold banding breaking up the uniform’s dark blue hue, Capt. Jonathan Archer sits motionless in a fat, royal blue mass of a chair that looks like an art-deco interpretation of a student’s classroom desk. Archer is lost in thought in his cramped Ready Room, which is sparsely furnished with brushed aluminum accents. The room’s low-slung ceiling features joists resembling metallic skeletal ribs that are just out of reach – when one is seated. In short, the Ready Room is the type of closet you’d find in the bowels of a ship or submarine. But a true bearing on the setting can be gained with a glance at one of the short walls, where four mounted sketches depict vessels progressing from sail to space. Each bear the name Enterprise, but the last sketch is the most important: it depicts a saucer with two trailing warp nacelles. This is the Enterprise NX-01.

The Ready Room’s door chime stirs Archer from his concentration. “Come in,” he says without looking up. What follows is an unexpectedly long pause, and his eyebrows furl in puzzlement. The door never slides open. “Or don’t come in, I don’t care,” he says matter-of-factly. Archer, also known as actor Scott Bakula, smirks and shrugs as the production crew’s laughter resonates throughout the set. Standing outside the ship’s Bridge in Paramount’s Stage 18, I can’t help but join in while I watch the comic miscue unfold.

A cry of “Cut!” resounds from the darkness as a grinning LeVar Burton emerges, pulling headphones off his ears. Burton, who could be seen on the other side of the cameras in his role as The Next Generation’s Georgi LaForge, is directing the “Terra Nova” episode of this new Star Trek series, which has been simply titled Enterprise. “Who’s on the door?” calls out the amused, script-wielding first assistant director Jerry Fleck, a longtime Star Trek crewmember.

Whereas Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Voyager became entangled in complicated and continuous alien race-wars, Enterprise takes a bold step back in time: the Federation has yet to form, there are no phasers that can be set to stun, and the transporter is voodoo technology at best. Set in the 22nd century, a short time after first contact with Vulcans and 100 years before the original 1960s series, Enterprise, with its rather contemporary crew, explores the galaxy with renewed awe and wonder. The show will answer the question long debated and hypothesized by Star Trek fans: what was space travel like before Capt. Kirk?

In leading this journey of discovery, the brash Archer commands an intrepid crew that includes the advising Vulcan Subcommander T’Pol (Jolene Blalock), Chief Engineer Charles “Trip” Tucker III (Connor Trinneer), British armory officer Lt. Malcolm Reed (Dominic Keating), helmsman Ensign Travis Mayweather (Anthony Montgomery), communications officer Ensign Hoshi Sato (Linda Park), and the alien doctor, Phlox (John Billingsley). These adventurers have the first encounters with Klingons and other alien favorites. There’s even a new menace, the Suliban, a genetically enhanced superspecies who are the pawns of an unknown time-traveling group.

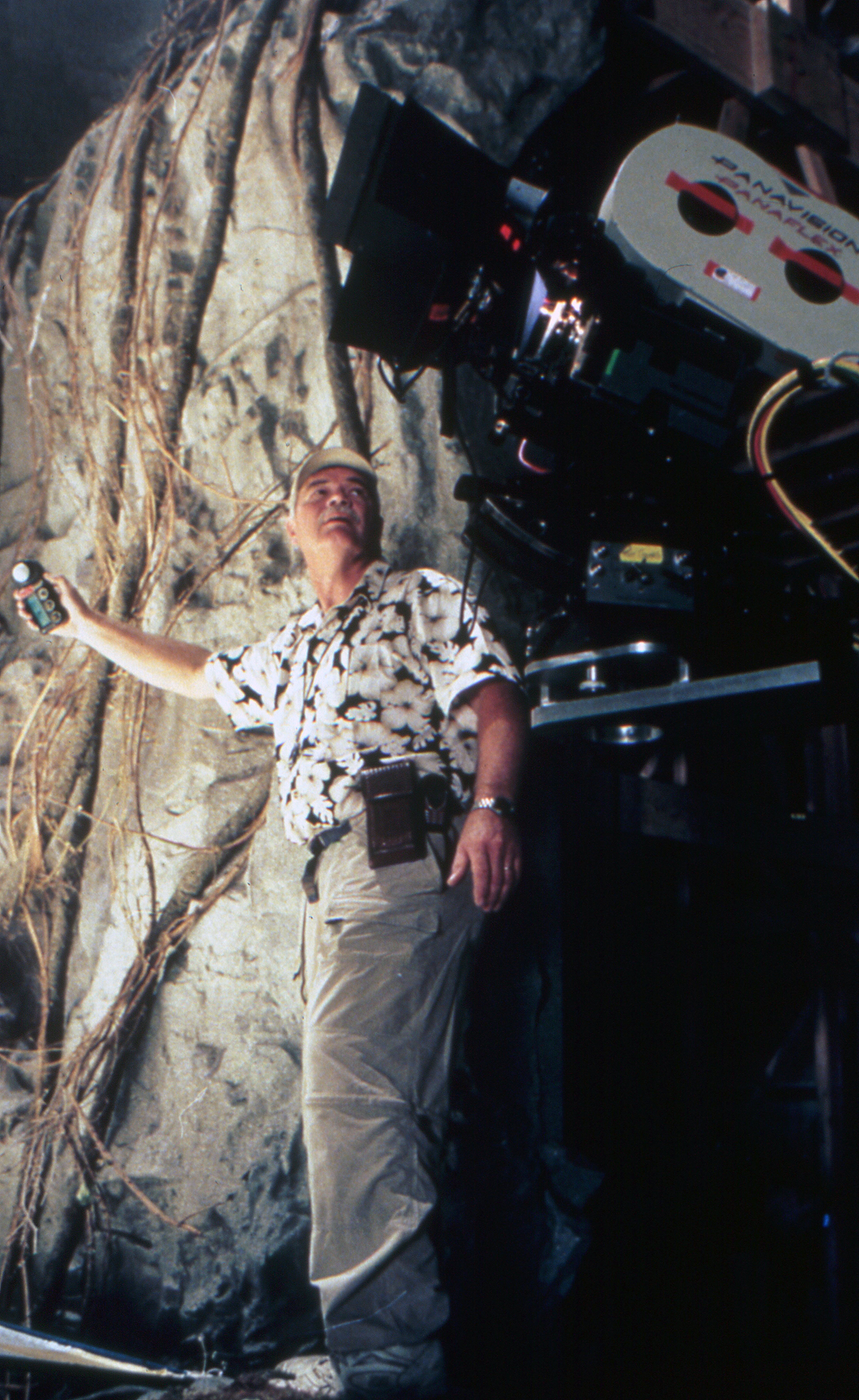

All of these actors are new to the Star Trek scene, but there are many familiar faces behind the scenes. In fact, a majority of the Enterprise production crew are Trek veterans, including director of photography Marvin V. Rush, ASC, who enlisted during the third season of The Next Generation series and has been photographing Starfleet’s TV adventures ever since. On this new show, however, it’s evident that excitement pervades Stage 18. “The original Star Trek influenced generations of people,” Rush says. To prove it, he points to the cell phone clinging to my hip. “Look at the flip phone from Motorola. Doesn’t it look like Kirk’s communicator? That’s not an accident. Star Trek and science fiction can influence the real future, so we have a chance to be a part of that, if we do our job right.”

Rush has a special fascination with space travel. His father, an aeronautical engineer for the Apollo space program, was involved with the design of the lunar-ascent engine that lifted astronauts off the moon’s surface. Coming up on his 13th year at the helm of the Star Trek series’ camera department, the younger Rush has been exploring uncharted reaches of the galaxy in his own way: on film. “It’s hard to walk away from a really great job for some unknown,” he says with a touch of irony. “I like the people I’m working with, and I like the stories we tell.”

“I think he is a brilliant cinematographer,” attests executive producer Rick Berman, who along with Brannon Braga has been a caretaker of the Star Trek world since creator Gene Roddenberry’s death a decade ago. “More importantly, after 13 years, Marvin comes to work every day and approaches each setup as if it were the first day of his first season. His enthusiasm and his unceasing desire to creatively find the best solutions to problems blows us away.”

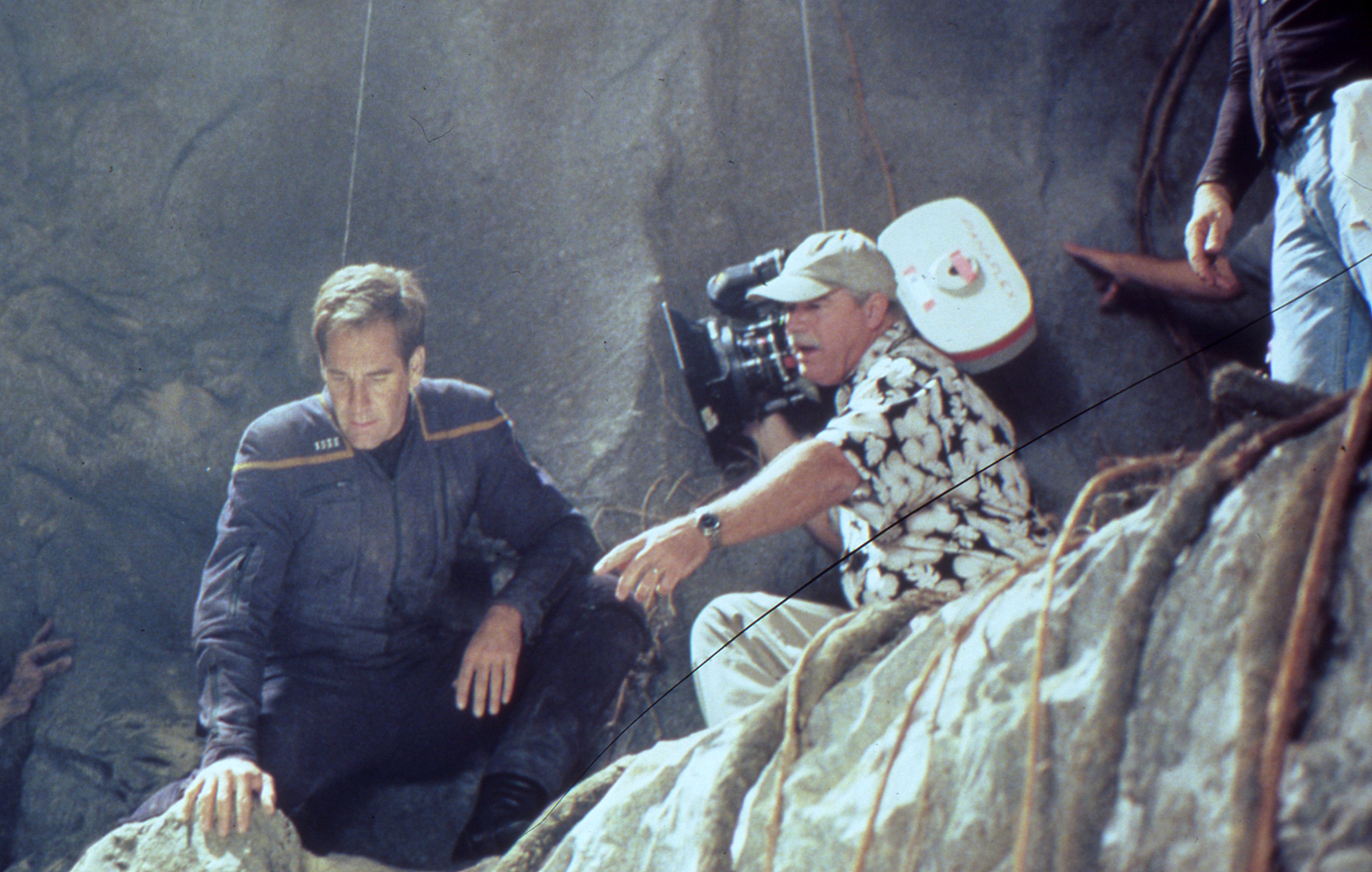

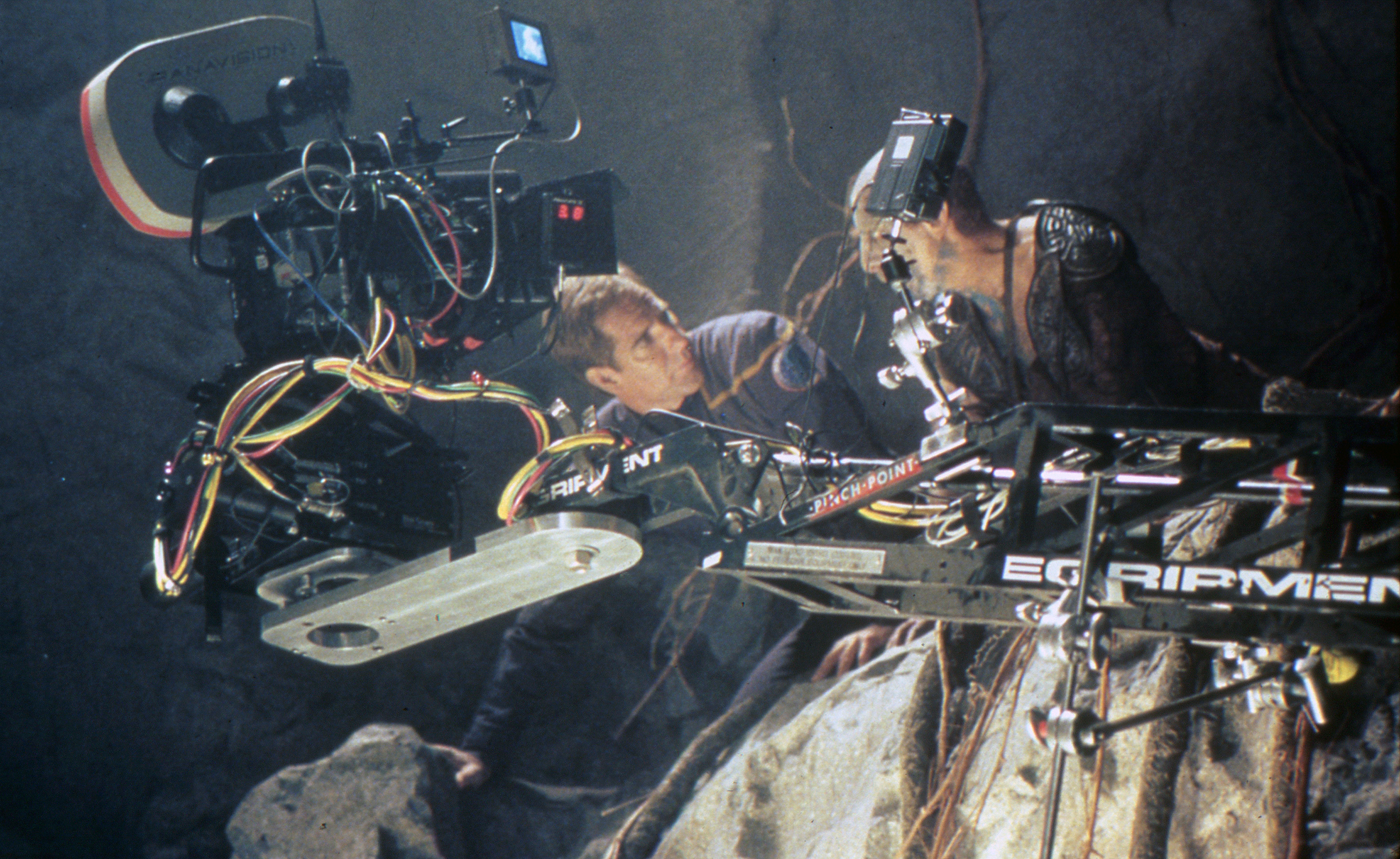

Rush and the crew relish the challenge of improvisation. After finally nailing the shot with that pesky door, Rush suggests to Burton that for the next setup, they should shoot over the tiny desk in the opposite corner from where Archer is seated, catching Mayweather and Sato in the foreground as they play a message recorded on a disk. In an instant, a wall is unscrewed and whisked away as the dolly carrying a Panaflex Gold II, the main studio camera, is set in place.

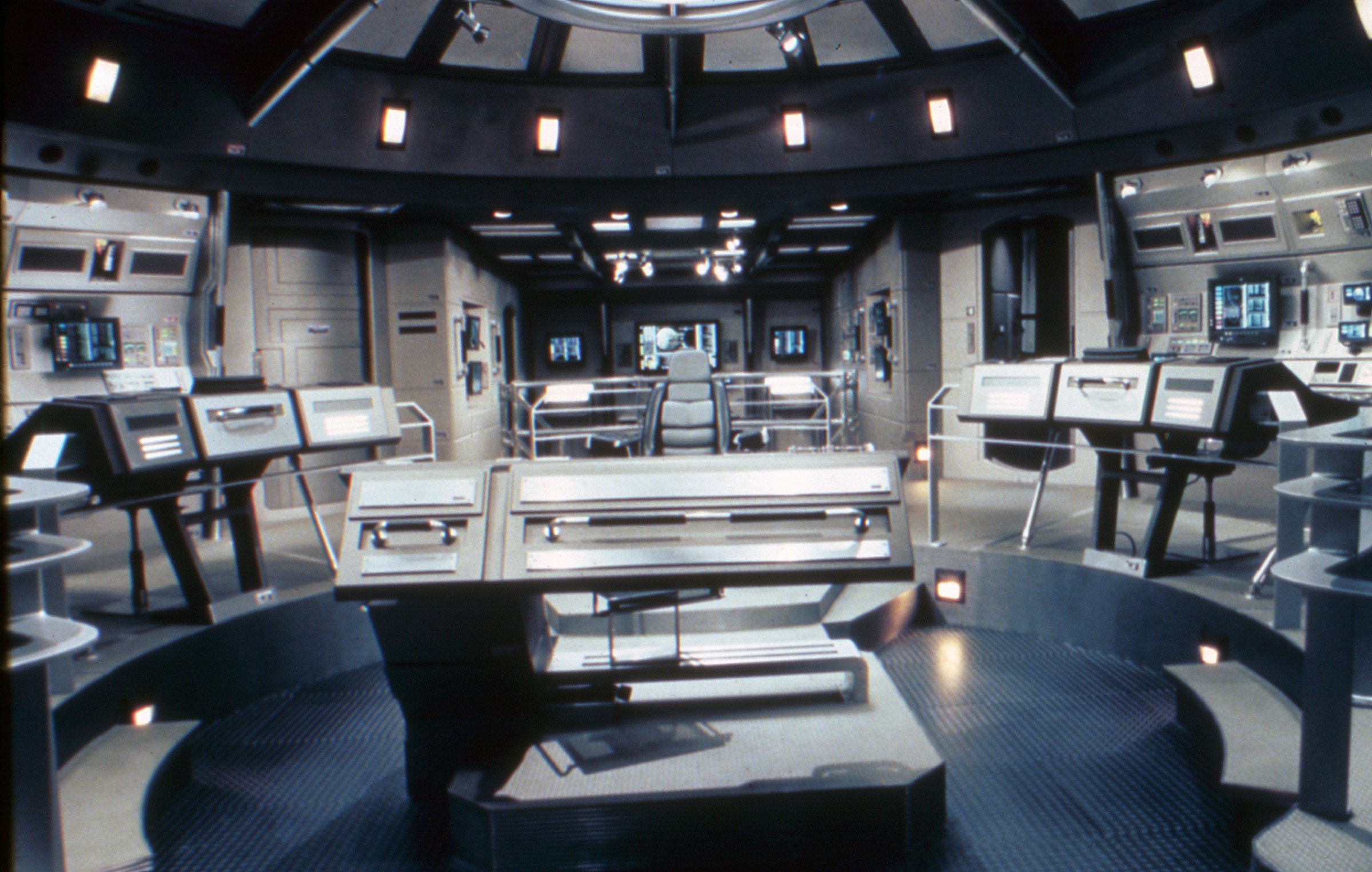

Production designer Herman Zimmerman constructed these mostly enclosed sets with an abundance of wild walls, creating endless shot possibilities. Stage 18 is home to the Bridge, Ready Room and Situation Room, as well as the engineering section, the shuttle bay and some corridors. Stages 8 and 9 contain sick bay, the mess hall, living quarters and swing sets.

The Enterprise interior, dressed in shades of gray and metallic textures, looks like a close cousin of today’s nuclear submarine, and Rush’s lighting plan follows that familiar scheme. “The director of the pilot, James Conway, and I actually screened The Hunt for Red October, which I’m a really big fan of,” says Rush. “If you notice the American submarine, this is a lot closer to that look, with recessed lighting and other units that are visible in the shot. We’ve created this sense of task or workspace lighting, and the sources are in the shot. In other words, areas and workspaces are lit from natural, practical sources. We occasionally have lens flare, but that’s all part of the look – if we think it’s working for us. We’re trying to lend this show more of that cinéma vérité, ‘you are there’ quality.”

Rush points to one of the many small units that have been incorporated into the set. “These are quartz lights, and we built little diffusions for them. For the wide shots, they provide a majority of the lighting for the set, and the same is true with the fixtures in the ceiling. These lamps are essentially household track lights that you can buy from a catalog. We found a design that looked modern and futuristic, one that Herman Zimmerman and I agreed was good for the show. They’re harder to flag because they’re not ‘movie lights,’ but we can shoot 360 degrees in this set without using any movie lights. These things have made the job easier in some ways and also artistically more liberating. When we go in for close-ups, of course, we’ll augment the look. But the object here was to make the set do 90 percent of the work and then be able to tweak the practical lights in a way that would look good and also look real.”

Much in the way that a painting is showcased with an overhead spotlight, Rush’s small fluorescent and quart lights illuminate the set’s work areas. A large cache of tiny Par 16, 20 and 30 bulbs is always close at hand. These bulbs, ranging from 35 to 60 watts in both flood and spot modes, have a color temperature slightly warmer than a 3200°K that is timed out. No matter which unit is used, all share the common trait of having very short, 3' throws.

Above the sets, hanging from a maze of pipe and chain, are bar 4' fluorescent tubes sleeved in Minus Green along with countless snooted Tweenies providing an overall ambient light level. “There’s an ambience to the set that we can take up or down depending upon the mood of the scene,” Rush details. “Sometimes when scenes get hairy and things are blowing up, you want to lose some ambience and maybe change the keys from being frontal to being more cross and back. But you still need to see everything.” The Bridge set has a high ceiling with segments of opaque Plexiglass through which these lights shine.

However, the same fixtures are readily visible above the Ready Room, which has low joists but no covering. “It’s an intentionally low ceiling because we want to create a sense of claustrophobia,” the cinematographer explains. “While that’s right for the designer and the storytelling, though, it is also inevitably one of the more difficult things to light. There are no really good angles from which to bring light into the actors’ faces. Although there are a whole bunch of Tweenies up there, they’re not useful for close-ups; we basically just use them to get exposure in our wider shots. Ultimately, we go in and relight for the close-ups, or we construct the shot in such a way that there are a few little toeholds where we can hide what we need. From a lighting standpoint, the Ready Room is the hardest set.”

After a dolly has been locked in place to prepare for an upcoming shot in the Ready Room, chief lighting technician William Peets oversees the quick installation of one of these small lighting additions in a joist toehold. This particular unit, a kind of homemade fluorescent softbox with diffusion on the front, is affixed to the high-tech structure with a few low-tech staples.

There are a number of these differently sized, handcrafted units about – even a shopping cart overflowing with them. Each unit contains one to four short fluorescent tubes with internal ballasts. They are designated with terms such as Albatross and Hot Pocket, nicknames that were created “so that everyone would know what we’re talking about,” Rush explains. “We needed to make lightweight fixtures that we could place anywhere. I had suggested to key grip Randy Burgess that he build something that would utilize the regular practicals yet allow us to control the light, and he dreamed these up. They’re made with a lot of Velcro and foamcore, they’ve got an adjustable snoot to extend the light out, and they also have frames that we can drop Frost [diffusion] into. If I want a harder light, I take the snoot off and remove the diffusion, but the homemade units have the same quality and color temperature as the practicals in the set. Some of the boxes contain multiple fixtures, so we can just unplug one for easy dimming.”

As he picks up a 2' variation of the foamcore units, he explains that “this is an example of another tool we’ve invented for our purposes. It’s called a Monitor, and it’s essentially a handheld eyelight. It’s got black on the inside to ensure less light reflection. I can have a fully steep key on somebody, and then I can bring this eyelight in and just nail him. It can be manually operated during the shot to finesse the look a bit.”

To the eye, the level of the shadowless light appears rather low, but Rush maintains a general exposure of around T2.8, exclusively using Kodak Vision 500T 5279 rated normally. “The 79 has tremendous latitude. That allows us a lot of creative freedom; we’re able to push the envelope further onboard the ship to create a unique look. That was the requirement – something we hadn’t seen before.”

Television’s current transitional state initially required the cinematographer to shoot in Super 35 but frame for full-frame 4:3 while protecting for the widescreen 1:78:1 aspect ratio, which created some difficult compositional compromises. However, midway through the season, the production has decided to use only the letterboxed 16x9 (1:78:1) aspect ratio. Episodes filmed previous to that decision will be re-telecined where necessary to have the wider picture extracted from the high-definition master via pan-and-scan methods; these shows will then be aired in letterboxed form. Rush is able to protect for this by using a special ground glass with 16x9 framelines that are undersized by 10 percent, leaving extra width and headroom on the negative. “Our actual picture is inside what we’re protecting for,” he explains.

Development is handled by Deluxe, and telecine is done in hi-def using a Cintel C-Reality at Level 3 Post. The HD transfer is then down-converted for NTSC. With time not being one of teleproduction’s best assets, one-pass color correction occurs at the time of telecine and is handled by George Svetlekana. During their 11-year working relationship, Rush has actually followed Svetlekana whenever the telecine operator has changed facilities. “I don’t think it’s very common for a cameraman to have that long a relationship with a telecine guy,” says Rush. “But timed dailies are what you see on the air; we don’t have a secondary color-correction pass. That approach requires us to nail it, so we have to have a good telecine man.”

A short distance from the dolly, which is resting where a wall had once been, Rush takes a seat behind a monitor and the two steering wheels of the Hot Gears control box. He uses the remote controls to show Burton what this angle of the Ready Room shot will look like with a 75mm Super Speed Z Series MKII lens, as first AC Gary Tachell adjusts focus with a Preston Microforce remote unit. “Oh, Marvin, this is great!” Burton exults at the success of another improvisation.

“One of the tricks around here is having a lot of capabilities, a lot of talented people and a lot of equipment so we can improvise rather quickly,” Rush says over his shoulder. “Flexible people and flexible thinking allow us to do something like this. If we can find ways to get the work done quickly, we can spend more time doing the things we want to do artistically.

“I like a light camera,” the cinematographer says when quizzed about his choice of lenses. “The Z Series are lighter lenses, and they work great. We’ll occasionally use Primos if we need something special, something specific like a focal length we can’t get any other way. I use the Cooke 5-1 [20-100mm T3] zoom as our workhorse, and I use it like I would a dolly. That requires a fine touch.”

A lightweight Panavision Millennium XL serves as a second camera for multi-camera sequences or as the main camera for handheld shots. Basic lens filtration on the show is a ½ White Tiffen Pro-Mist, which “adds a bit more life to the shadows,” notes Rush. A Soft/FX I is used for cosmetic applications in close-ups, and a Soft/FX 2 is employed for extreme close-ups.

As the Ready Room setup undergoes some final tweaking (such as gluing the recording disk back together after it accidentally falls apart in Bakula’s hand), grips easily remove the frontal wild wall of the Bridge set to prepare for the next batch of shots. The Bridge, with the Situation Room in back, begins to resemble a futuristic version of St. Peter’s Square – but with a ceiling.

Other crewmembers lay track into the nose of the Bridge and prime an Egripment Javelin crane, the key piece of equipment added for the new show. In fact, the multi-tiered sets were constructed with this crane in mind. “The design of the Bridge set is tied into the notion of using the crane for primary coverage,” Rush points out. “The benefit of the crane is that we can float in and out, playing out a shot very quickly. We can actually fly right over the furniture and into a close-up, and we do shots like that all the time. Imagine laying dolly track for this! Because of the multiple levels we’d have to roll out, it would be a nightmare. Without [the crane], this set would be unshootable, in my opinion. This way is much more efficient, and time is the commodity we have the least of.”

The Bridge is home to the usual stations familiar to Star Trek fans, and is thus surrounded by a vast array of plasma and small LCD screens. The advantages of using these flat-panel displays are that the need for phasing has been eliminated and they can be photographed at extremely oblique angles. The displays are fed non-interlaced graphics originating from Macintosh Cubes, meaning that for HDTV, every field of video will have full resolution for a level of detail unattainable with video playback and CRTs. Graphics are controlled from a hut referred to as “Mission Control,” off to one side of the stage.

Rush steps away from the monitor, and Douglas Knapp, with a crack of the knuckles, takes a seat behind the Hot Gears remote wheels. Knapp, who pulls double-duty as first-unit camera operator and second-unit director of photography, quickly practices the camera moves that will glide from actor to actor in the single sustained take. “We rely on the abilities of talented people,” Rush says. “If it weren’t for Doug being a terrific operator, I wouldn’t even attempt a shot like this. Finesse is required, and he has to be right on the money on cues that are kind of rubbery.”

As Knapp works on the timing of the moves, Peets is setting marks on a dimmer he has patched into the fluorescent fixture hidden in the joist, dimming the light about 50 percent when Bakula moves near it and ramping back up when he walks away. “With these short throws, the lights get bright really fast,” explains Rush. “Billy is dimming it down to take care of that when [Bakula] gets close. The light is fluorescent, so it doesn’t change color temperature [when it’s dimmed].”

Stage 18 falls silent as the call for quiet is shouted and the bell sounds. Everyone’s attention is fixed on the Ready Room as Archer, Mayweather and Sato listen closely to the recording of the Terra Novan leader’s final words. As the shot unfolds, Knapp orchestrates the twin wheels while Peets rotates the dimmer dial.

“It’s all a little dance, you know?” Rush whispers. At the end of the take he gives a subtle nod. “Bingo. That was the shot.” Everyone else knows it too, and they head to the Bridge for the next setup.

“I’m very proud of the look that we’re achieving,” Rush concludes. “It’s a look I haven’t done before, and it’s a lot of fun to learn this new landscape. I’m very eager to have a big audience for this program, because Star Trek poses a positive view of the future. My dream is that this show will rekindle the excitement of exploration, of the absolute unknown, of discovering what’s out there.”

This article was originally published in American Cinematographer, November, 2001. Some images are additional or alternate.