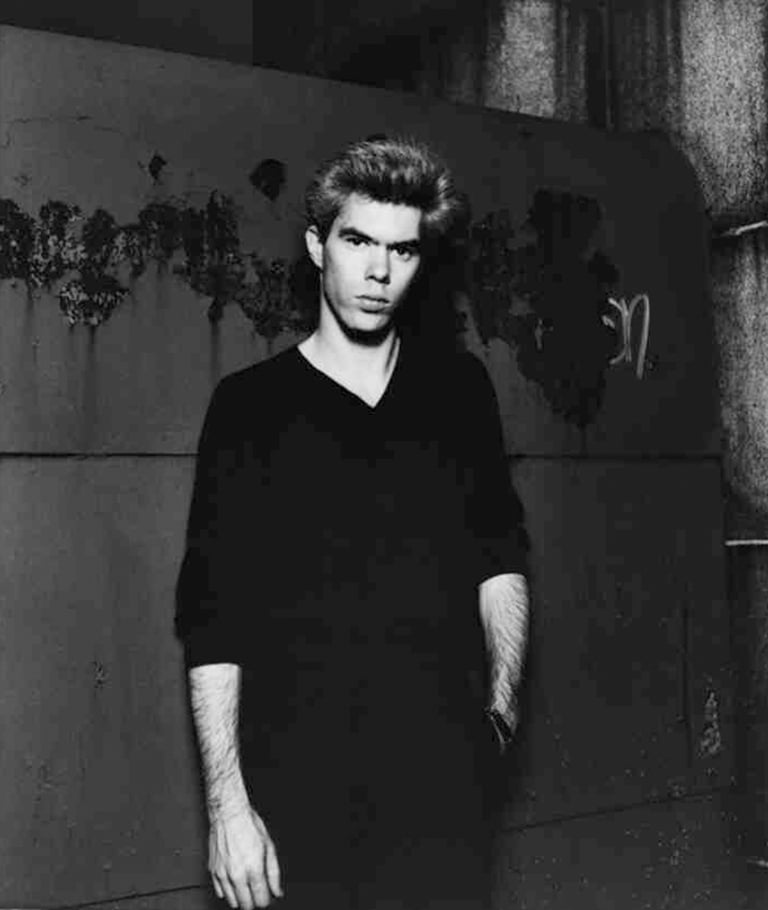

Jim Jarmusch and Stranger Than Paradise

“The beauty of the film is that it’s got a vitality all its own because it was created out of almost nothing,” says cinematographer Tom DiCillo.

This article originally appeared in AC, March 1985

Two years ago, Jim Jarmusch had an idea to make a short half-hour film with his friends who were actors, musicians and fellow alumni of New York University film school. He made the film for $8,000 and while he edited the short, Jarmusch wrote the second two-thirds for a feature. The film made the rounds in Europe and won several critic awards. Armed with the minor success of his first feature, Permanent Vacation, and the short, the poet-turned-filmmaker approached various producers for additional funds to complete the film, Stranger Than Paradise.

“I was meeting producers,” recalls Jarmusch, “giving them my script and discussing many possibilities. Some of them were liars and some of them were sincerely interested in giving me a good deal. I wanted to own part of it and I wasn’t interested in giving away something in which I had so much invested. Finally, this guy came along who had a great story about how he would produce the film, own half and stay out of the production completely. A few people had said this to me before, but, when I saw the terms on paper, it said something entirely different.”

The guy was Otto Grokenberger, a young influential producer who was active in German television and independent filmmaking. To Jarmusch’s surprise, Grokenberger’s contract arrived substantiating the verbal agreement and a partnership was formed.

Stranger showed promise, but, at the time, no one foresaw that it would become an international sensation, winning the Camera D’Or at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, Best Film, at Locarno, Switzerland and becoming a cause celebre of independent filmmakers everywhere.

“I’m still a little confused by Stranger’s success,” states Jarmusch. “I thought that formally and structurally the film would keep audiences at a distance, and it would become a cult film in Europe and there’d be little interest in America.”

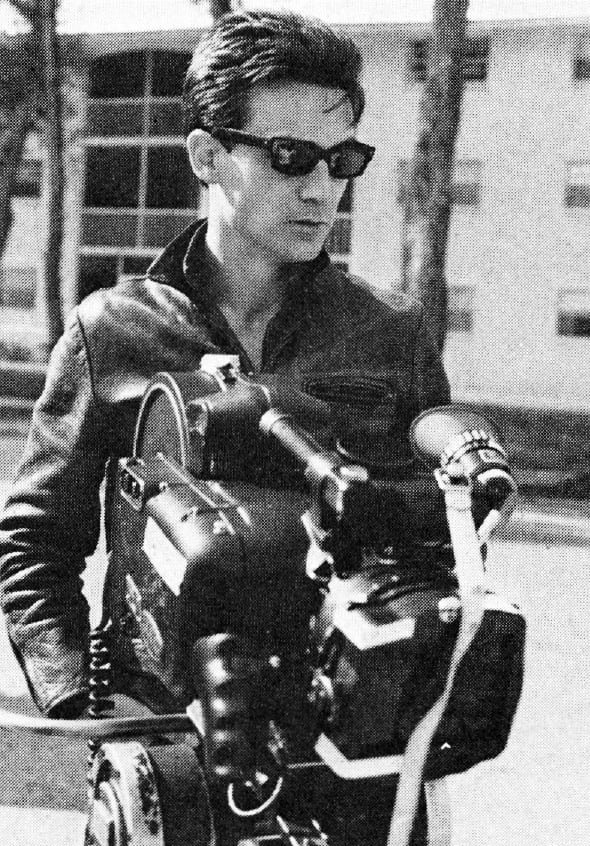

Filmed in grainy black-and-white on 35mm stock and shot in forced perspective, the film presents a stark look at reality that tells a simple story in a series of vignettes. Told with minimal dialogue, action and emotion, the strong visuals are heightened by stylized rhythm and editing/cutting to black. The bleak imagery, reinforced by an eclectic soundtrack, allows Jarmusch’s deadpan humor to surface, imbuing the film with quirky vitality.

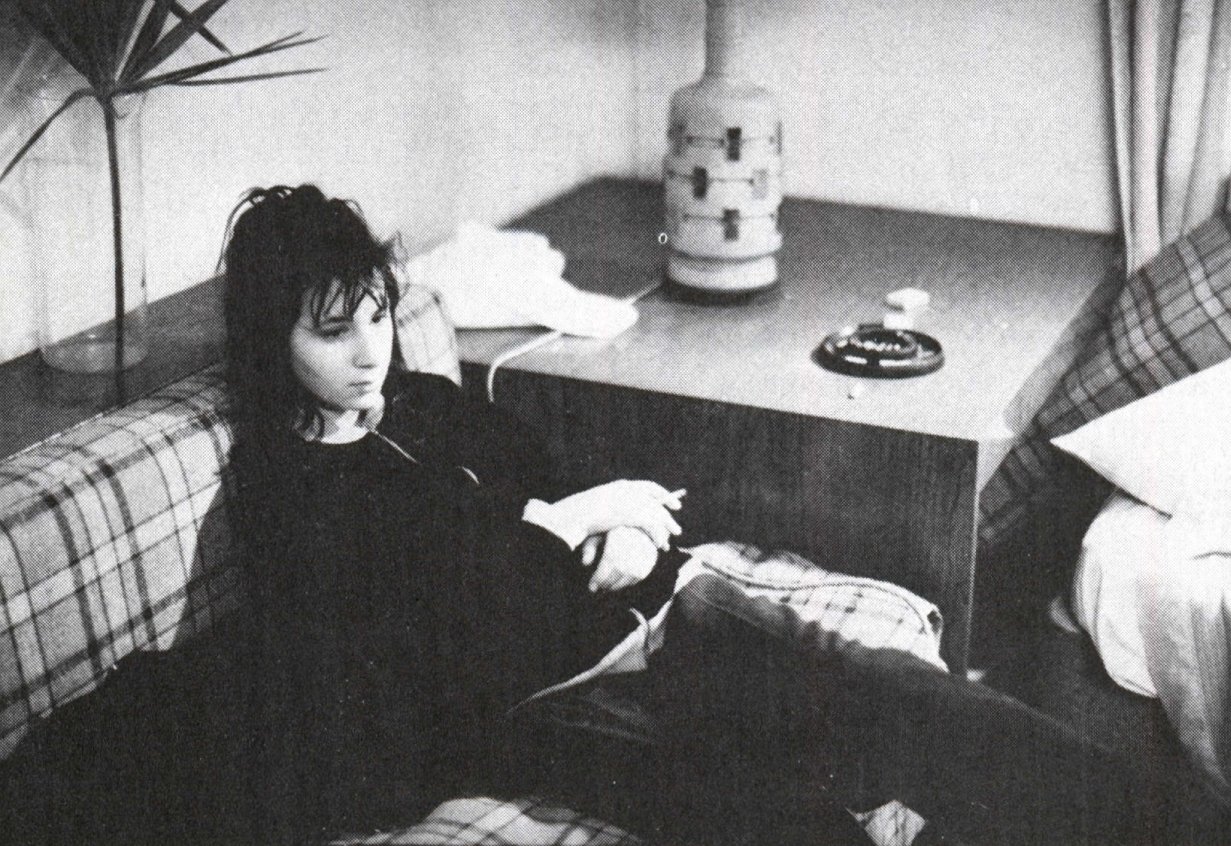

In synopsis, Stranger Than Paradise, is a story about three young individuals who are isolated in their own small world due to their inability to communicate their emotions. In the opening vignette, titled “The New World,” Eva, a young, raven-haired Hungarian girl in her late teens arrives in New York. En route to Cleveland to live with her Aunt Lotte, Eva stays with her cousin Willie, also a Hungarian, who immigrated to the “New World” 10 years earlier. To both Eva and Willie’s disappointment, the one-night stay turns into 10 days. Eva’s visit in one of the most exciting cities in the world is limited to Willie’s pathetically small, one-room apartment and American culture is garnered from TV shows, comic books and Willie’s limited perspective. Eddie, Willie’s buddy, is her only other contact. Slowly, Willie’s attitude changes towards his light lipped, matter-of-fact cousin and the two find a strained closeness.

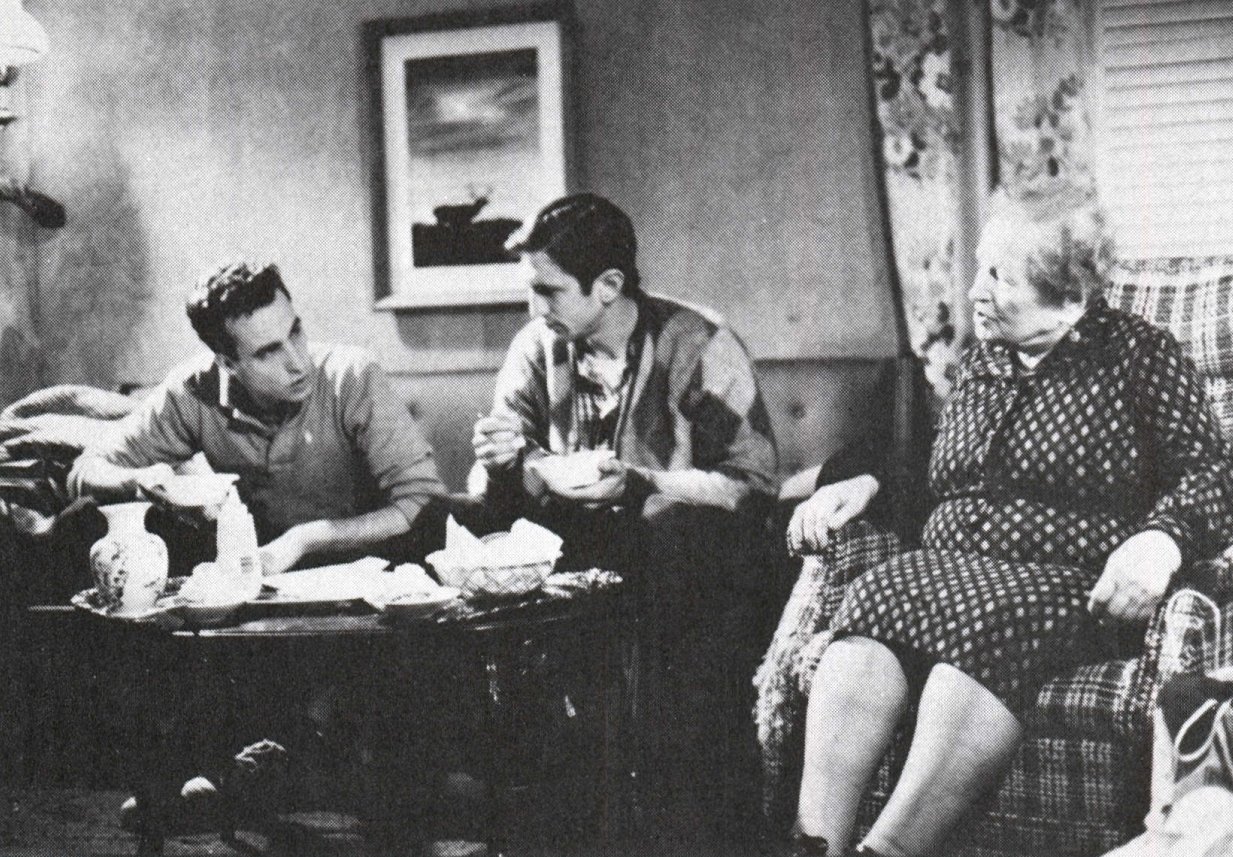

“One Year Later,” the second segment, Willie and Eddie win a bundle of money in a crooked poker game and decide to split for Cleveland and visit Eva. The two long faced buddies whom the film’s editor, Melody London, calls updated versions of Ralph and Norton of The Honeymooners-arrive in Cleveland in mid-winter to find Eva living a bleak existence.

For diversion, Willie and Eddie play cards with Aunt Lotte and eat bowl after bowl of homemade goulash. Meanwhile, Eva entertains a lackluster young suitor. Out of boredom, the New Yorkers leave Cleveland. On the road home, they realize that they have only spent a grand total of $50 of their original $600 and they decide to blow the money and head south to Florida. But first they rescue Eva and take her with them. In the final vignette, “Paradise,” to their dismay they find Florida a cold formidable foreign territory. Fun and relaxation eludes them and Eva becomes acquainted with the amenities of a cheap seaside hotel. Willie and Eddie revert to their old habits and go to the dog races, losing all their money. Eva consoles herself by reading comic books and playing her well-worn tape of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ song, “I Put A Spell on You.” From this point on, confusion builds as the three characters become separated. Eva considers returning to Europe while Willie and Eddie win back their money at the horse races. Willie and Eddie find Eva gone and head for the airport. Willie buys a ticket to get Eva off a Budapest bound plane and the plane leaves. The closing scene is of Eva returning to the motel.

Working with a total of $130,000 to complete the film as well as making the two films two years apart come together as a whole proved a taxing but exciting experience for all involved.

“I love black-and-white because it suggests a style of life removed from life. The medium lends itself to an expression of life that is altered.”

— cinematographer Tom DiCillo

Cinematographer Tom DiCillo compares the creation of Stranger as similar to garage rock where “you go into the garage and knock out the sound. The beauty of the film is that it’s got a vitality all its own because it was created out of almost nothing.” Not surprised by the success of the film, DiCillo, who is a paradox in filmmaking since he is now pursuing an acting career, sees the film in a unique light. “In New York, people were making films that were limp. Jim’s work got out of the New York style and stands on its own. It has certain artifices, while at the same time it has the feel of ‘Hey, look what we picked up at the junk pile.’”

For producer Sara Driver, the task of pulling the production in on budget was a feat of imaginative bargaining. Driver, who prides herself on getting a lot for a little, has worked with Jarmusch for the past five years. According to Driver, “We made Permanent Vacation [a full-length feature shot on 16mm color reversal stock] for $15,000. That’s when I learned about making ‘below-low’ budget films. Then I directed my own film, You Are Not I, which Jim shot for me. That was 50 minutes and made for $14,000. I had to blow up three cars, which I pulled off for $50 and the help of 30 volunteer firemen from New Jersey.”

“The second part of Stranger was shot on location in Cleveland and Florida,” added Jarmusch. “I guess we could have shot the Cleveland stuff in Long Island City which would have helped since the budget was so low. But for me, being on location is very important.”

Echoing Jarmusch’s sentiments about the locations, DiCillo, after recently viewing the film, found it to be “filled with the most desolate locations on earth.” This desolation is heightened by the wide-angle lens perspective and the use of black and white. Both director and cinematographer agree that the film would have become an entirely different story if color had been used.

DiCillo, whose strong background in black-and-white stills combined with his writing abilities got him into film school, sees shooting in color analogous to “shooting in a candy store filled with a lot of little jelly balls. You have to become very substractive when dealing with color. I love black-and-white because it suggests a style of life removed from life. The medium lends itself to an expression of life that is altered.”

Jarmusch sees the extensive use of color in today’s film as more of a marketing tool than as an artistic device. “I think it’s sad the way color is used. Usually, color is the standard because people have to shoot color to sell it to TV or whatever. Color can be used so beautifully, but usually it’s just taken for granted. Black-and-white just doesn’t give you as much information.”

In essence, Stranger is a testament to the unique properties of black-and-’white and a survivor in a vanishing technology. The first segment, “The New World” has a very grainy, gritty almost dirty quality. In contrast, the rest of the film is a cleaner, sharper print. Once again, budgetary constraints account for the differences. “The New World” was shot with leftover film which Jarmusch, then Nick Ray’s assistant on Wim Wender’s film Lighting Over Water received as a donation.

“This was processed at a slop lab in New York,” remarked Driver. “It’s very difficult to find someone who can process good black-and-white. DuArt matched the second part quite well. We were in Florida and Cleveland and would send the dailies up to Don Donigi at DuArt and he’d give me great daily reports. They’re good, but, like everyone else, they can make mistakes.”

For the New York Film Festival, Driver and Jarmusch’s company Cinesthesia Productions wanted top-notch prints. What was shown provoked film critic Vincent Canby to write an article in the New York Times which stated that the film looked as if it had been sitting on a windowsill for a year. Driver, who attributes the poor print quality to a company strike, pulled the film from the lab. Driver returned to DuArt with the negative after Samuel Goldwyn, the film’s U.S. distributor, had a difficult time pulling satisfactory prints.

“The prints from DuArt,” says Driver, “are now very beautiful. They have a wonderful silvery finish to them.”

Time limitations compounded with limited resources became critical during the filming of the second segment. According to DiCillo, “There was more pressure on the second shoot than the first. We were trying to make Cannes so we had to work very fast, shooting all day, every day for two and a half weeks. With such a tight schedule we had some near disasters. But I like to work fast. It brings out an element of freshness and you have to be creative. Also, Jim and I have a good working relationship because we’re so different.”

Due to their personalities — Jarmusch, the pensive, studied poet, as opposed to DiCillo’s electric, open, intuitive presence — they find their similarities and disparities a boon to their working relationship. This bond between the two formed while at NYU. “When Jim first talked to me about Stranger,” notes DiCillo, “I saw it as a very strange comic strip. The idea of doing each scene as a single take struck me as a single frame of a comic. The fact that there are no cuts forces you to look into the scene and see what is happening.”

“Where Jim and I fought was when he wanted to keep the camera away from the characters — distant. I’ve learned that if you’re continually distant, the image on the screen will die for the viewers. Not that I want TV close-ups, but I want to be closer.”

Jarmusch finds that DiCillo’s way of looking at things is very different than most cinematographers because he is also an actor. “Tom’s much more aware of the way certain characters move and other small details. Working with him is very exciting. He’s shot a lot· of film and has been a running thread through New York’s cinema. Tom’s sense of timing and movement and his use of light amazes me. He’s very poetic with light in a simple way. He doesn’t make it naturalistic but rather goes for effect and creativity.”

DiCillo accounts for lighting as the result of working with limited equipment. The bizarre light patterns that happen in the interior scenes in “The New World” were the result of working with “rinky-dink” 8mm lights which annoyed DiCillo to the point of forcing him to throw them out half-way through the breakneck two-day shoot. Using the last light left, he threw one bright line of light, coming from an irrational light source, out over the set. To Jarmusch’s satisfaction, DiCillo was able to create the look which was followed throughout the film.

Using an Arriflex-BL, DiCillo found using just two lenses, an 18mm and a 25mm, a fascinating exercise, yet his first priority is to what is in front of the lens. “I like to penetrate with the camera, to penetrate what is really happening. I look through the lens not for composition but for the life within the frame. That life is either within the objects or the actors. I think this is due to my training as an actor.

“But working with two lenses was exciting because most of the shots had to sustain themselves after two or three minutes with no cuts. I like things to happen accidentally. The composition continually rearranges itself within one frame.

“The last day we were in Cleveland, Jim wanted to shoot the lake. He thought it would be great. The sun was out and the fact that there was snow on the lake was to be part of the joke. No sooner did we get there and set up, but a snow squall came in off the lake. There we were shooting in the middle of a blizzard. It has the effect of looking into a ball of cotton — a total void.”

Sometimes, according to his own admission, DiCillo’s inexperience threw a cog in the wheel of production. Problems, which were later corrected with opticals, resulted on the Florida shoot due to the fact DiCillo was minus a ground glass with TV demarcations. He began framing for 1.85. The ordered glass never arrived and an hour before the crew packed up, Jarmusch was informed that the mike was in every frame.

Sound problems also plagued Stranger. London, who had dropped out of NYU to pursue a career in political documentaries, found the sound of the first part very different from the last segment. “Jim and I were very concerned because not only was the sound different technically, but the character of Eddie was so much more evolved in the second half. He’s so silent in the beginning. Jim kept asking me, ‘Is this the same Eddie?’”

“The sound recordist [Drew Kunin] had a hard time because the shots were so wide and he didn’t have a boom person and had to go it alone. The dailies would arrive with Drew’s apologies. Plus, the sub-zero weather in Cleveland made things very difficult."

To correct these problems, London and Jarmusch worked feverishly covering them with tome and redubbing in an attempt to send a completed film to the Cannes review. Editing difficulties were compounded by the low budget which prevailed.

“Usually, the budget for a documentary is around $60,000, for a half hour film. On Stranger we had a much lower budget. We edited at the Editing Machine in the Film Center Building on 9th Avenue. It’s really a grim place and the machine wasn’t very good. To make things tougher, we didn’t even code the film in sync.”

At first glance the way the film is edited appears simple or as if it was edited in the camera. Yet it is a highly sophisticated exercise in precise rhythm. Jarmusch had conceived of the structure before he and John Lurie, who plays Willie and is the film composer, wrote “The New World.”

For editor Melody London, Stranger was one of the most unusually challenging films to cut. “I loved editing in black-and-white. It’s beautiful. I’d study how the black leader and the shots would come together. In the composition, the element would move in and out of the picture. Working with Jim was very unusual because unlike most people I’ve worked with, Jim has a clear vision of the film. In that sense, my contribution was not as huge, but he was always open to suggestions. We worked very hard to leave the scene on an abrupt, ironic or comic note. Something that would make people laugh.

“Sometimes the lines didn’t work. In fact, we changed the whole ending in editing. Originally scripted, Eva goes to the airport and you clearly see that she is not going to get on the plane. I thought that it was more interesting to leave this more ambiguous. I pushed strongly for the change. It’s much more in keeping with the stylistic format of the film.”

Jarmusch is fascinated by unconventional twists taken by the plot. “The idea was not to cater to any expectations from the audience. The plot and structure are so minimal that if you stop the film at any moment and ask the audience what is going to happen, they’d have no idea. Tightly scripted or plotted films draw your attention to the form of the plot and I want to stay away from that.”

London questioned the idea of black leader as a constant pause between each scene. “I thought we should vary it because people would become aware of the formula and possibly become bored. Jim found this idea seductive but then he thought it would provoke analysis: ‘Why are they now going to white?’

“Experimenting with black was a complex process. We tried six seconds, then two, then five. Literally, we cut hundreds of precise lengths of black leader and cut them into the film. We would screen each version of the film in its entirety weekly at DuArt. Finally, we arrived at four seconds.”

At this point, John Lurie came into the edit room to work on the score. The soundtrack is a romantic bittersweet waltz that borrows heavily from [Béla] Bartók. Twisted into a unique sound by added elements of black music, Lurie’s unique compositional style is totally homogenous with Jarmusch’s visuals. Lurie brings to Stranger his background as leader of the New Wave band The Lounge Lizards and numerous film scores. In juxtaposition to the score is Eva’s favorite song, “I Put a Spell on You.”

Jarmusch actually built the story around Hawkins’ memorable 1956 blues tune. “I wanted Eva’s character to have some icon of American culture that she had attached herself to in Budapest. It’s her idea of America. It had to be something offbeat, not Michael Jackson or something more predictable. Plus I love Screamin’ Jay. It had to be black, which for me is the essence of American music. It’s the only rock-n-roll song that I can think of that has a waltz tempo. More importantly, thematically, ‘I Put a Spell on You,’ fit her character because she is a catalyst for any action that Willie and Eddie take. Without her, they are very indecisive.”

Due to Jarmusch’s and Lurie’s intense collaboration throughout the film, controversies arose in the editing room. “There was a controversy about the music in the driving scene. Jim felt strongly that the music should be cut and then picked up on the other side of the black leader. John had written it as a continual piece, and I had to agree with John. By this time, the editing room was a psychodrama. I was the psychiatrist, and they were both on the couch. If you have so much invested artistically in something, you’re gonna fight like hell to have your ideas represented. In that film, everyone’s personality is there. That’s why there’s an incredible balance.”

The sound mix was handled by Jack Cooley of Manhattan’s Magno Sound. His background as a musician and sensitivity to rhythm proved invaluable during the arduous sessions. “Jack was bewildered by some of the technical elements with sound dissolves and changes of the reel,” recounts London. “Jim and I did not want the black spaces to be voids. On the end of every reel there was black with a sound fade, then the next reel had black with sound carrying over. Jack would say ‘You guys are making so many problems for yourselves.’ He was sure the whole thing would fall apart and be butchered in projection.”

Stylistically and cinematically, Stranger evokes a sense of denial, and the repression of any sexuality adds slight tension. Jarmusch prevented any physical interaction between the characters and his direction to do so was a constant annoyance to the actors. Their frustration was apparent because of the actor’s input into the content of the characters in the second part of the story. “The story is so simple, and people’s sexuality is something really delicate,” states Jarmusch.

In editing, London would kid Jarmusch and point out possible sexual innuendos which heightened his fear that the film would be analyzed on this level.

Interesting enough, Jarmusch is presently writing his next film which is a love story dealing with teenage sexuality. “I’m superstitious and will not say anything more about it.” The young, silver-haired filmmaker pauses then adds lightly. “Only that it will be low-budget and devoid of any cliches.”

For DiCillo, his determination to act is his paramount concern. “After I shot Permanent Vacation, people were coming up to me saying, ‘I want my film to look just like that.’ There’s a danger that people will just see the style of Stranger which is so alluring and not see what’s within the style. I hope that we won’t see imitations of this film.

“People think I’m crazy when I could be out shooting and making money. But I’d rather paint apartments and study acting than let cinematography take me someplace I don’t want to be. So, it’s tough now. I was on a shoot the other day as an actor for Mark Rappaport’s Chain Letters. He came up to me and looked at me kind of funny. He said, ‘You’re a cinematographer, aren’t you?’ I answered, ‘No, I’m an actor.’”

“It’s hard for independents to keep going,” reflects London. “It gets discouraging finding money yet I’m very particular as to what I work on. As an editor you give a lot of time, a lot of care... you give your heart. I would never want to treat the craft as a money-making facility if I had to trade in interesting work.”

After Stranger, London produced a political documentary about Nicaragua called It’s the Real Thing. Driver is due to begin production on a feature. DiCillo has made the commitment to pursue his ideals in an even tougher arena, in front of the camera rather than behind it. What if he can’t make it? “I guess, before I’m one foot away from landing on the Bowery, I’ll beg for a dime, call up and say, ‘Hey, Jim. You need a gofer?’”

This BTS footage, shot on Super 8 film, demonstrates the film’s no-frills production approach:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.