Schindler’s List Finds Heroism Amidst Holocaust

Cinematographer exploits black-and-white’s somber palette for Spielberg’s World War II drama.

By Karen Erbach

Unit photography by David James

Twelve years after arriving in the United States as a political refugee, Janusz Kamiński returned to Poland to photograph Steven Spielberg’s stirring interpretation of Schindler’s List. Kaminski came to Chicago in 1981 speaking only enough English to order himself eggs and toast. After enrolling in a language course, he moved on to study film at Columbia College in Chicago. He completed his education at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles as a cinematography fellow, and later served an internship with John A. Alonzo, ASC on Nothing In Common.

Kamiński seized the opportunity to shoot his first feature, Grim Prairie Tales, by cold calling a production listing in The Hollywood Reporter. Since then, he has gone on to shoot 15 features, including Cool As Ice, Wild Flower, Class Of ’61 and The Adventures Of Huck Finn. Kamiński’s longtime gaffer and friend, Mauro Fiore, also a Columbia College alumnus, flew out to Los Angeles five years ago on the hot prospect of gripping on a Roger Corman film, Not of This Earth. Kamiński and Fiore have worked together ever since.

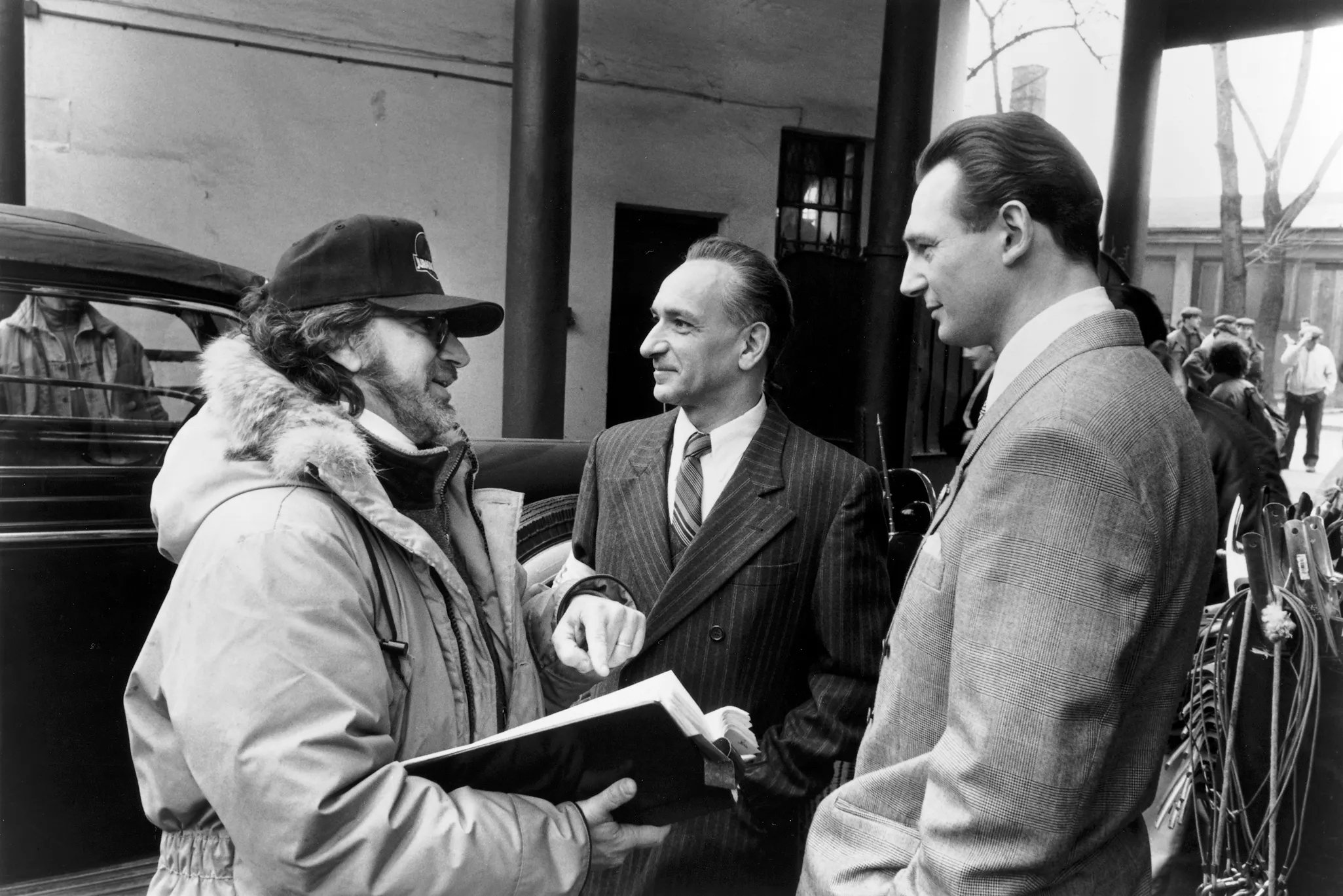

Shooting for Steven Spielberg unquestionably marks an acceptance into Hollywood and catapults Kamiński into a different league. How does one make the leap from low-budget features to high-profile projects such as Schindler’s List?Kamiński replies, “Wild Flower got me the job. Steven watches a lot of television and caught Wild Flower, which was directed by Diane Keaton, on Lifetime. The next day, I received his phone call offering me the [Amblin-produced Civil War] TV movie Class Of ’61. Looking back, I think maybe that movie was a test because later I found out he had also been considering me for Schindler’s List.”

After the completion of Class Of ’61, Spielberg and Kamiński met again. By then Spielberg had decided to offer Kamiński his next, very personal project, Schindler’s List. The director solicited Kamiński’s thoughts about shooting in black-and-white, and also asked the cameraman if he was comfortable doing a film that would undoubtedly garner international publicity. Spielberg encouraged Kamiński by telling him, “You just did a beautiful movie for Amblin in 22 days. It would be amazing to see your work on a 75-day shooting schedule.”

“It shows what one person can do with the power that they have.”

— Janusz Kamiński

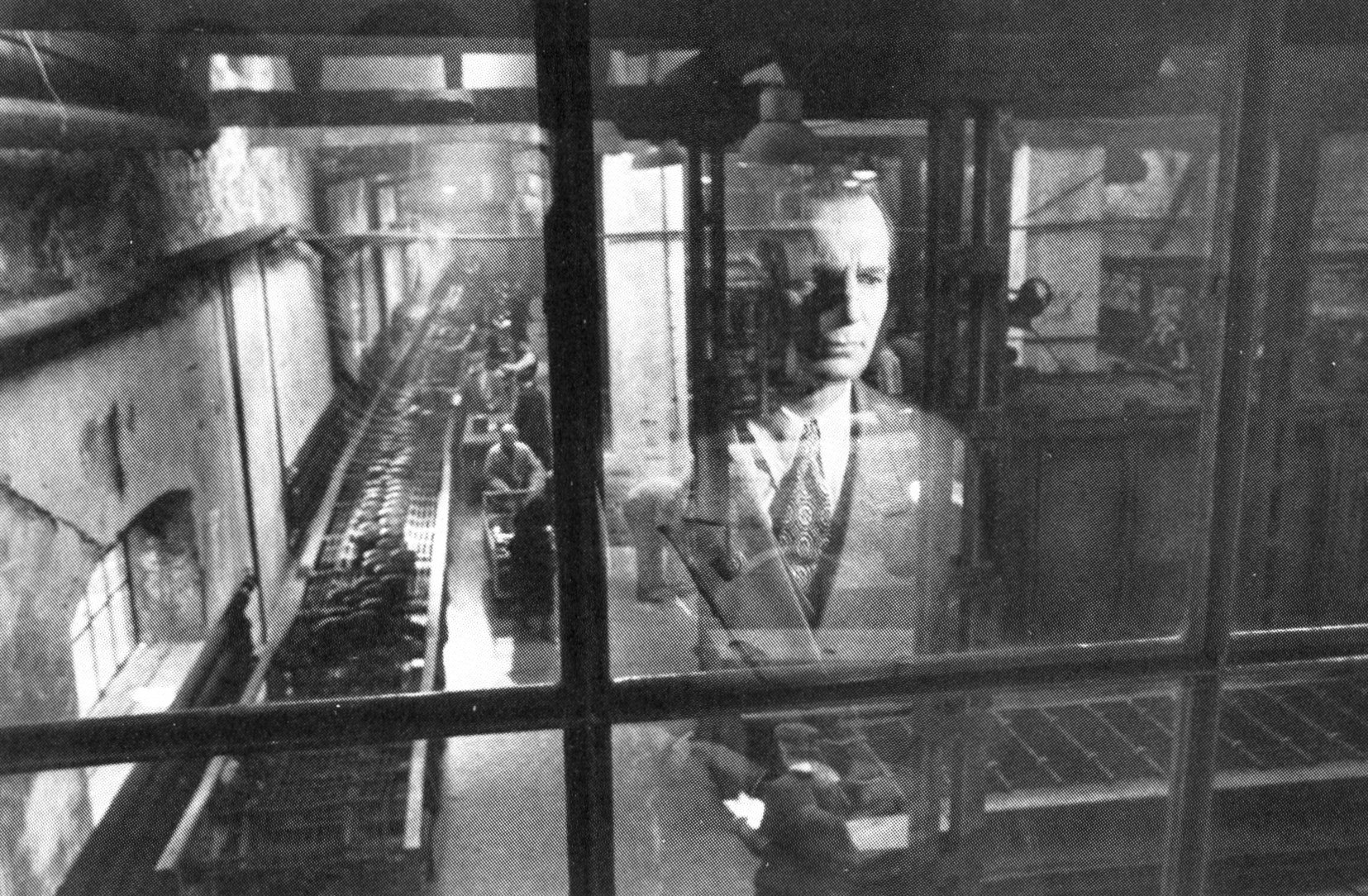

And so it began. Spielberg, Kamiński and a fine international crew set out for Poland to film the inspiring and poignant story. Based on Thomas Keneally's book, Schindler’s List is the true account of Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), a German Catholic industrialist whose membership in the Nazi party ironically helped more than 1,300 Jews escape extermination. A womanizer and heavy drinker, Schindler became an unlikely hero by taking over an enamelware works in Krakow and creating a benevolent and humane work camp for the Jews.

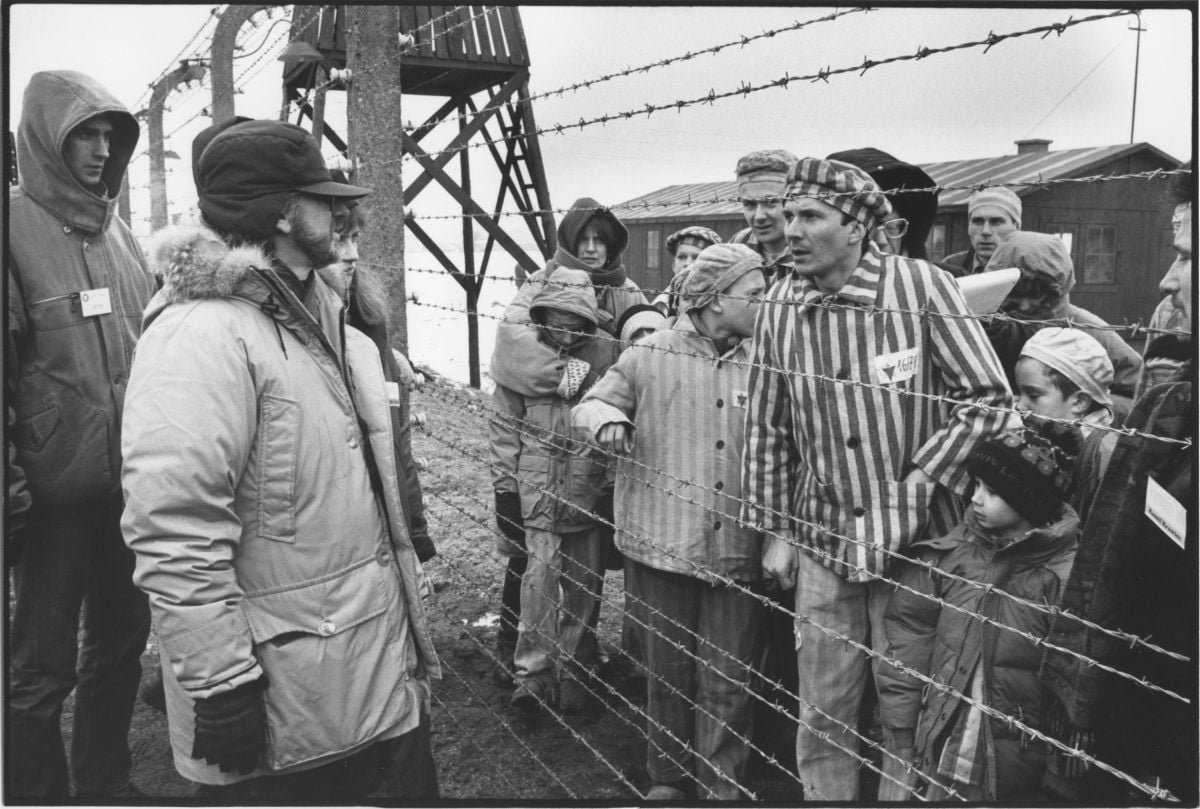

For Kamiński, the experience touched him on both personal and professional levels. “Here I am [after] 12 years in the United States, going back to the country where I was born, accompanied by Steven Spielberg. I was ecstatic to be working with Steven, and yet when we began filming it brought home the sickening reality of the Holocaust. The newsreel quality of the black-and-white seemed to fade the barriers of time, making [the footage] feel like an ongoing horror that I was witnessing firsthand. I think I can speak for the whole crew when I say the experience was sobering.”

Kamiński expressed an initial pride in returning home to Krakow, only to be deeply discouraged by recurring anti-Semitic remarks aimed at the cast and crew. “Although I’d like to romanticize about returning to Poland, I realized that America is really my home,” he says.

Kamiński knew for a year and a half that he’d be shooting Schindler’s List, and he used the preparation time to learn more about black-and-white photography by studying books from that era. “I used A Vanished World by Roman Vishniac as sort of my bible. Vishniac photographed Jewish settlements in the period between 1920 and 1939. I found inspiration in that book because this man, Roman Vishniac, had nothing — inferior equipment, inferior film stock and only available light — yet he managed to create really beautiful pictures with a timeless quality. When you look at the book you really don’t know when the photos were taken except for giveaways like clothing and street signs and such.”

“You also have to remember that Spielberg has wanted to make this movie for 10 years. Perhaps Jurassic Park closes one stage of his life and Schindler’s List represents a new one.”

shot of what Jewish women saw upon arriving at Auschwitz.

Historical preparations were also important, and although the retelling of World War II genocide was part of Kamiński's education, he felt further study would only benefit his photography. “You try and get as close to the subject matter as possible,” he says, “hoping that the knowledge will evoke the emotions you have about the period and will ultimately contribute to your creativity.”

As the director and cinematographer were completing work on separate projects (Spielberg was directing Jurassic Park and Kamiński was shooting Huck Finn) they found time to meet and view films such as In Cold Blood and The Grapes Of Wrath. Kaminski points out that “although we discussed the styles and techniques of Conrad Hall and Gregg Toland, we were far from making creative decisions about Schindler’s List. We primarily watched the work of others to see how style could create mood.”

Once Spielberg and Kaminski were in actual pre-production, the time had come to finalize decisions, such as which film stock to use. Against studio hopes, the final print of Schindler’s List would be black-and-white. The filmmakers had to decide between shooting on black-and-white negative or draining the hues from color negative. Spielberg wanted to colorize specific elements in certain shots, ultimately forcing the duo to utilize some color negative. Kamiński’s big concern was whether the manipulated color would match with the black-and-white.

“After doing some tests, we used Kodak color 5247 and 5296 to match with black-and-white 5231 and 5222, which are the only available emulsions,” explains Kamiński. “We had to really fight with relatively inferior and dated film stock, basically because technology has changed but the film stock hasn’t.”

Kamiński worked with Don Donigi from Du Art to devise some tests. The first test Kamiński performed was to find out if a manipulated color negative could pose as black-and-white. “We had two cameras, side-by-side, with the lenses at the same focal length, shooting simultaneously. One was loaded with 5296 color negative. The other had 5222 black-and-white negative. Don printed the 5296 on color print stock but pulled out all the color. The black-and-white was printed on standard black-and-white stock. We set up the projectors side-by-side for viewing. The black-and-white had a completely different quality than the drained color negative. The black-and-white looked much more realistic, with more grain, while the color had a faint blue tint.”

Since Kamiński wasn’t satisfied with the look, Donigi conducted another test. He explains the concept and results, in layman’s terms: “Black-and-white negative film is made up of silver halide and printed on silver release positive. Color is made up of silver coupled with dye. When the silver gets exposed it ignites the dye, creating color images. During the bleach and fixing process, the silver comes out of the film and all that remains is the dye. When we tried to print the color/dyed image onto black-and-white release positive it was unacceptable. This is because the print stock is orthochromatic, all you pick up is the blue information of the negative. I decided to print the color negative onto a special panchromatic high-con stock which is sensitive to all colors and used primarily for titles. Because this high-contrast stock has virtually no middle greys, I altered the process in order to extend the greyscale.”

Kamiński recalls his impressions of Donigi’s tests: “When I saw the results I was just blown away. They were so beautiful. From 5296 he printed it on this panchromatic stock and broadened the range. The results were amazing — no grain, no haze.”

The next phase of testing involved filters. Kamiński explains how he was trying to brighten faces so that they'd appear white rather than grey: “Sometimes I’d succeed, sometimes I’d fail. I used yellow #15 and orange #21 to brighten skin tones. The principles in black-and-white are as such: if you have a red object and you apply a red filter, the red object will become lighter. Because most people’s faces have a lot of orange, when you apply an orange filter, it neutralizes the orange, making the face appear lighter. With red filters, you have to be careful. We used red #23 on occasion, but the faces became too bright and the lips became too dark. Lips have a lot of blue in them and red accentuates this while increasing the contrast. Another technique was to ‘overlight’ the faces according to my meter; when we saw the dailies, they were the perfect tone of white.”

Another concern for Kamiński was how black-and-white film would interpret color tones. “We began the tests with makeup and wardrobe. We wanted to know how tones in the wardrobe would photograph because we weren’t dealing with color as a final result. But of course, color still had to be considered.

“For example, in color film, green and blue have distinct differences, but in black-and-white they read the same. This is because they have the same tone. But this is not the case in red and blue. The color red is not lighter than blue, but red stands out more in black-and-white because the tone is brighter. For this reason, tones became more important than colors. I worked with both Alan Starksi, the production designer, and Anna Biedrzycka Sheppard, the costume designer, to coordinate the tones, making sure that they were either brighter or darker than skin tone.”

Kamiński thought he’d solved all his problems with black-and-white — that is, until shooting commenced. “We began to have problems with the negative discharge of electricity that happens only with black-and-white because of the silver content in the emulsion. We would have spots on the negative that looked like little dots with arms of lightning. Sometimes we would have lines running across the top of the frame like lightning in the sky. It’s very hard to avoid, and we failed. I still don’t know how to avoid it. I read some comments in American Cinematographer by Walt Lloyd, who shot Kafka, [and he said] that he had the same problems. Basically, the room has to be static-free. We’d spray the room and be careful when loading or unloading to avoid any friction between the winds of emulsion. Soon we realized that a lot of the static occurred at the beginning of the roll. So we’d shoot off 60' to 80' at the head of every roll, providing [some room] to protect ourselves. However, there’s still some footage that has static and people will see it. I don’t think it's terrible — the image is not ruined — but it’s unavoidable. We were shooting under harsh weather and production conditions. All those elements contribute to static discharge.”

Don Donigi at Du Art reports that he hears similar stories from other cinematographers and divulged some tricks brought back from the field. One involves placing a humidifier in the camera truck and blowing air to deionize the environment wherever the film is loaded or rewound. The most original idea was sticking a damp sponge inside the camera unit, assuring moisture.

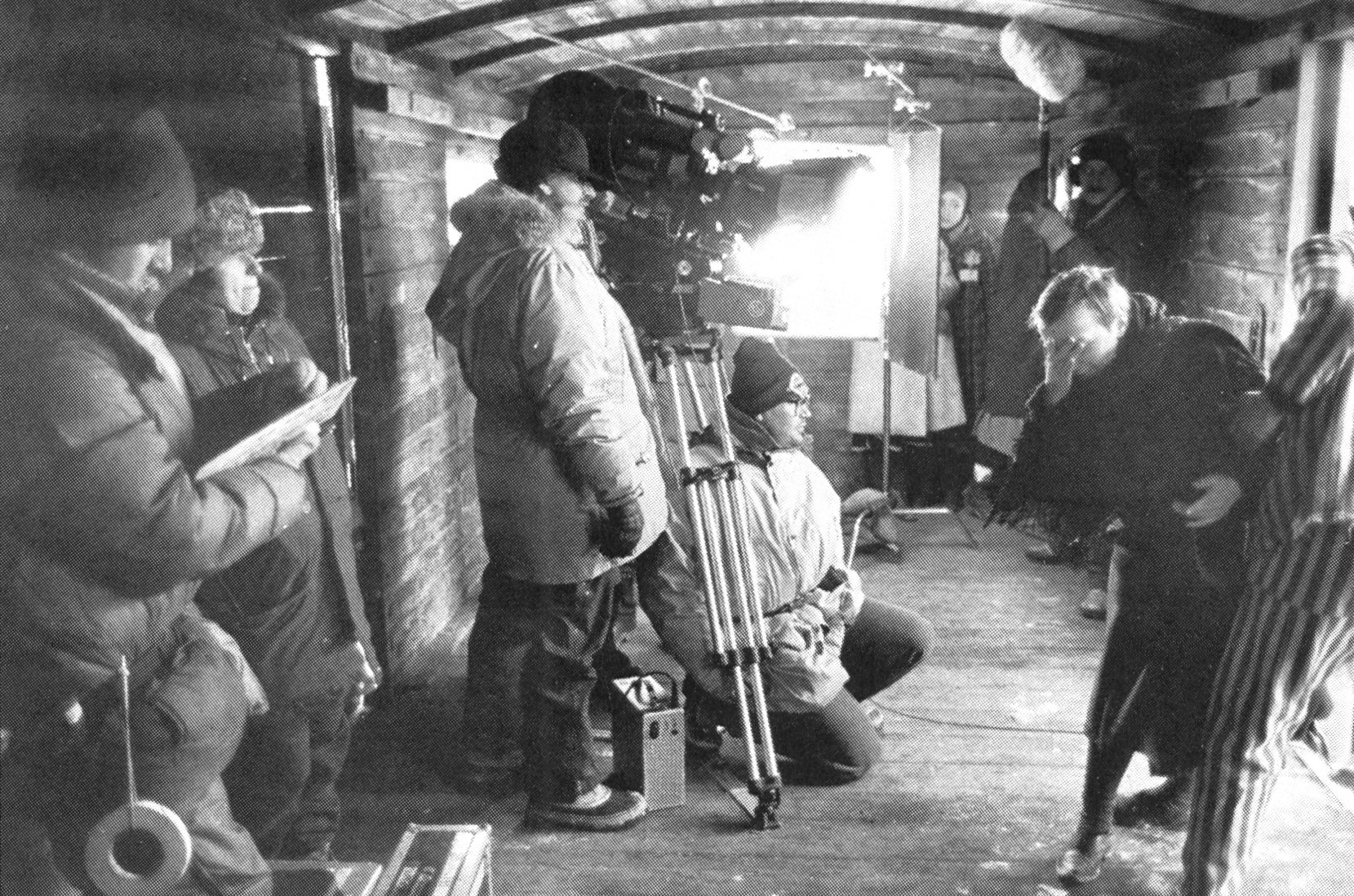

Kamiński also confronted the logistics of shooting in a foreign country, with all of the potential problems regarding equipment and manpower. Fortunately for Kamiński, he was able to bring with him longtime collaborators, some of whom spoke Polish. “I have a crew here in Los Angeles that I've worked with for five years,” he relates. “Mauro Fiore has gaffed every movie I’ve photographed, and we’ve reached a point where he can light many of the scenes without much discussion between us. Steve Tate, my first assistant, will share credit with Stevie Meizler, my second AC, who pulled focus on all B-camera and handheld shots. I also brought my best boy electrician, Jarek Gorczycki, whom I met at AFI and who, coincidentally, moved to America from Poland at about the same time I did. I was secure with the electrical crew chiefly because of Mauro and Jarak. I was a little worried about the foreign grip department. In general, Europeans don’t use grip equipment like Americans, who are so specialized. If you want a little shadow on the wall, you’ve got the equipment. In Europe, if you want to create shadow you have to cut it from a piece of cardboard.”

“Mauro was extremely helpful,” Kamiński adds. “It’s easy for me to say, ‘I’d like some lights here, and some there,’ but he’s actually the one who had to deal with the logistics and the language problems.”

On one occasion, after Fiore had rigged a second-story interior with Condors and many lights, Kamiński turned to him and said, “That looks nice; now let’s turn everything off.” Then he turned to Spielberg and said, “Steven, this looks great the way it is. We have enough daylight for two hours. Do you think two hours is sufficient time to complete the scene?” When Spielberg said that it was, the scene was shot with available light only, negating all of Fiore's efforts. Most of the time, however, Kamiński found himself using every single light that his gaffer had set up and then “kissing his hand” in gratitude.

Amblin Productions got its entire lighting and camera package from Arri. Kamiński used both the Arri 535 and the brand-new Arri 535-B camera. The 535-B camera is more lightweight than the 535 because Arri did away with all the electronics. It also has additional handles for easy transport. Arri made further adjustments for Kamiński, eliminating excess weight by removing the filter box brackets and adjusting the gate for the black-and-white film. Kamiński used the 535 as his “A” camera and the 535-B as the “B” unit. For Steadicam work, he employed a MovieCam.

Kamiński used Zeiss prime lenses, both Super Speed and Standard Speed, and felt that they were perfect for this film. “Because Zeiss lenses don't have as sharp an edge as the Primos, we got a very realistic look,” he says. “In addition, the minimal focus [of the Zeisses] is greater than the Primos, which allowed us to come closer to the actors.

We usually shot our closeups at around 29mm, which is something I would never do if I wanted to glamorize. I usually use a 50mm or higher. But for this film, the 29mm seemed to provide a more realistic effect.”

Kamiński arrived in Poland in January of ’93, Spielberg arrived in February, and shooting commenced in March. As production began, Spielberg and Kamiński still hadn’t discussed a specific photographic style for the film. “He gave me 100 percent free rein, which was really amazing for me,” Kamiński says. “It was very exciting. Steven has always employed a certain mood or those ‘Spielberg touches,’ but this movie has a completely different style than his previous films. Schindler’s List was shot in a very crude technical manner. We were kind of aiming toward imperfection, little so-called ‘flaws’ that might be considered mistakes, such as handheld shots in scenes that would normally be shot on the dolly. Often we would set up the Pee Wee dolly and then have the operator, Raymond Stella, hand-hold while sitting on the dolly seat.”

Kamiński saw a method in the “mistakes,” an integrity that surpassed style and flash. “I approached this movie as if I had to photograph it 50 years ago, with no lights, no dolly, no tripod. How would I do it? Naturally, a lot of it would be handheld, and a lot of it would be set on the ground where the camera was not level. We weren’t making dutch angles and shots like that; that was not the purpose. It was simply more real to have certain imperfections in the camera movement, or soft images. All those elements will add to the emotional side of the movie. When people go to see this movie and expect to see a Steven Spielberg blockbuster, they will find something else — a dark and unobtrusive tone. The performance that Ben Kingsley [as Itzhak Stern] gave was so subtle that very often I would not pick up on the emotional impact until later. But Spielberg was guiding this story in his own way, and the dailies projected an emotional wallop that made us all uneasy in our chairs. You also have to remember that Spielberg has wanted to make this movie for 10 years. Perhaps Jurassic Park closes one stage of his life and Schindler’s List represents a new one.”

Despite the freedom he allowed his cameraman, Spielberg still had some definite ideas about he'd approach some of the scenes. “For instance,” Kamiński recalls, “there was one scene when Nazis raid a ghetto. Steven wanted a flash effect [to simulate] machine guns firing in the hallways, but he only wanted to see the shadows of the soldiers. We placed two separate strobes at different heights, and as you look down the corridor all you see is the shadows of the soldiers created by the firing machine guns. We used a similar effect during a courtyard raid. We had a camera set outside in a courtyard and we placed seven strobe lights in various windows. On cue, we would hit. each strobe, giving the illusion of a massacre inside. That intercuts with the interior, where we see Germans shooting into the furniture, into the walls, and into the ceiling. The Jews would create fake walls so that they could hide. The idea was that we would see the Germans firing into the wall and then cut back to the exterior to see the windows flashing. All the while we would see the Nazis loading exterminated victims into the trucks. Then we cut back inside the building to see blood dripping from the walls.”

One example of Spielberg’s colorization idea was a scene in a town square where hundreds of Jews wait for Nazi officials to decide whether or not they would receive a “blauschein,” or blue stamp. The stamp would buy the Jews time by allowing them to work in branches of the Nazi industry that were essential to the war machine. Kamiński explains, “As the stamp is coming down on the document, Steven wanted the imprint to be a very faded blue. Everything else in the frame would remain black-and-white.”

Spielberg also used colorization during a scene in which a little girl wearing a red dress is running through a raid. “He wanted the girl’s dress colorized,” Kamiński notes. “That image has something to do with how strange life can be. There is this beautiful little girl with blonde hair wearing this red dress and running through this madness, where Nazis are arresting, shooting and dragging people off the streets. The little girl just runs through the crowd and nobody bothers to stop her.”

Kamiński says that surprisingly little planning went into the film, despite its broad scope. Spielberg had no storyboards, no shot lists, and very often would show up on the set not knowing exactly what he would do that day. One of the tools Kamiński incorporated in order to keep up with the spontaneous energy was a small portable tape recorder, which he used to record his thoughts about lighting, problems or equipment he might need.

When scouting locations, Spielberg would sometimes get ideas on how he was going to stage a scene. Kamiński would dictate those ideas and then later transfer them to the script so that he would be better prepared. "I'd make my comments to the lab, record what I'd done and what I was trying to achieve. Then later, when I saw dailies, I could compare my notes and see if I achieved what I wanted or if I failed. It was especially useful with black-and-white because I was still learning the medium. And on a daily basis, I would make adjustments, either through my lighting, exposure or filtration."

Kamiński offered to share some of the verbal and written notes he had made about several scenes. What follows are excerpts from the original script, along with Kamiński's thoughts on how he would light the scenes:

INT. GHETTO APT — DAY

Clothes boiling on the stove in big pots stirred by a woman in rags; sheets hanging from the lines stretched across the room over a few sticks of furniture; children with coughs; the Nussbaums staring in dismay from the doorway.

SHOOTING: "Sunset. Man shaving in front of mirror on wall. The man is not lit. The wall reads f4. I expose at f2.8. As the Nussbaums open the door, Mrs. Nussbaum reads f4. I expose at f2.8. As they walk into apartment it drops to fl.4. As they go into the other room they stand in a strong pool of light. I backlight Mr. Nussbaum at fl6. Mrs. Nussbaum will be a bit darker. When he turns to the camera he is the key at 2.8. To the eye the scene looks well-balanced."

DAILIES: "The scene was very contrasty. Moody. A sense of complete poverty and desolation. Not a pretty scene. I feel like the attention will be drawn to the "realness" of the situation and not to the photography."

EXT. COUNTRYSIDE — DAY

SHOOTING: "A locked off shot of a German staff car driving by. Dusk. Light meter shaded from sky reads fl.3, the sky reads split f2.8/4. It's getting dark and I fear underexposure."

DAILIES: "Looked good. It always amazes me how much light is actually caught even though the light meter tells me that it won't work."

Although Kamiński did his best to prepare, there are bound to be mistakes when a cinematographer doesn't have a storyboard or shot list and must deal with 100 speaking roles and 30,000 extras. He recognizes them freely: "In one instance, I had a strobing problem. It was a big dolly shot that we will not be able to use in the final cut. We were just dollying past too many objects too quickly. But sometimes you get excited and forget how technical it is to be a cinematographer. Also, I wish some faces from certain scenes shot earlier were brighter. I was exposing as if I would be exposing color emulsion and relying on what I knew the best. It was the beginning of shooting, and being insecure [at that point] you always rely on what you know the best. I mean, it'll work for the average audience, but in my opinion, it was a mistake. You have to be very honest with yourself and not listen to other people when they tell you it looks great. But you learn."

When asked about some of the most difficult scenes to shoot, Kamiński sighs as he reflects back on some of the interior factory scenes or night exteriors at the camp. "I was always worried about the factories. I'd never dealt with such a scope. I was not working with high-speed color emulsion; I was working with an emulsion with an ASA of 200. As I said earlier, if you expose black-and-white with the given ASA reading, you're not going to get the results you want, so you have to overexpose by putting in a lot of light. I would rate the 200 ASA as though it were 100 ASA, which meant that some nights we had every single light working."

Kamiński describes a particularly unsettling day: "There was a scene at Birkenau, where a group of women are being lead into a transfer room. They've been stripped of their identity and deprived of their privacy. Like those women, we don't know if they're going to live or die. They've been told they'll be showered and clothed in uniforms. But as we all know, very few got what they were promised. The Nazis liked to create a facade of normalcy to avoid panic among the prisoners. Also remember that during the transport to Auschwitz and Birkenau, these people were living for days in tightly packed cattle cars, without food or ventilation. Spielberg had some specific ideas on how to handle this scene photographically. I placed single light bulbs on the ceiling and along the walls. When the women were led into the shower room or gas chamber all the lights suddenly shut off, leaving the women in complete darkness. There were screams for 5 to 10 seconds until a strong spotlight came on and pointed toward the camera. The light outlined the nude women crowded next to each other, holding each other for comfort, not knowing whether they'll live or die. All of a sudden, the sprinklers came on and the water sprayed out. It's the most amazing scene. It's so emotional that even now, it's tough for me to hold a strong voice.

"What Steven did was to mimic Nazi sadism so that the audience, like the women, are in the dark, afraid for what could happen. It was not manipulative or sentimental. It was real. And the crew's reaction on the set was hatred — hatred for the ignorance that could do this to a group of people. But look, it's still happening in former Yugoslavia. Same stuff, 50 years later. What did we learn? Nothing. That's the purpose of the movie — to remind people that it's so easy to slip into the same thing."

One of the final scenes is the liberation of the factory and Schindler's final exit. His workers present him with a ring cast from their gold teeth. Inside the ring, the Hebrew inscription reads: "Whoever saves one life saves the world."

Kamiński describes the final moments: "We see an open field with puffy clouds. Hundreds of people are coming over the horizon toward us. The next shot is in color and in Jerusalem. It's a hot, dry land. We see hundreds of people again. But this time it's the real remaining survivors and their relatives walking toward us."

The next shot is in a Christian cemetery in Jerusalem, and the long line of survivors stretches toward the camera. In the foreground, we see Oskar Schindler's grave. Each person puts a pebble on the grave, and the little pebbles eventually become a mass of stones piled high; it's estimated that the roughly 1,300 people Schindler saved have produced close to 10,000 relatives.

“It shows what one person can do with the power that they have,” Kamiński concludes.

The cinematographer earned Academy and ASC Awards for his expert camerawork in the picture, which won another six Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director.

Kamiński has photographed every one of Spielberg’s feature projects since, including The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Amistad, Saving Private Ryan (earning his second Academy Award), Munich, Minority Report, War Horse, Lincoln, Bridge of Spies, and, most recently, their remake of West Side Story.

In 2019, Schindler’s List was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.