Sunshine: Let There Be Light

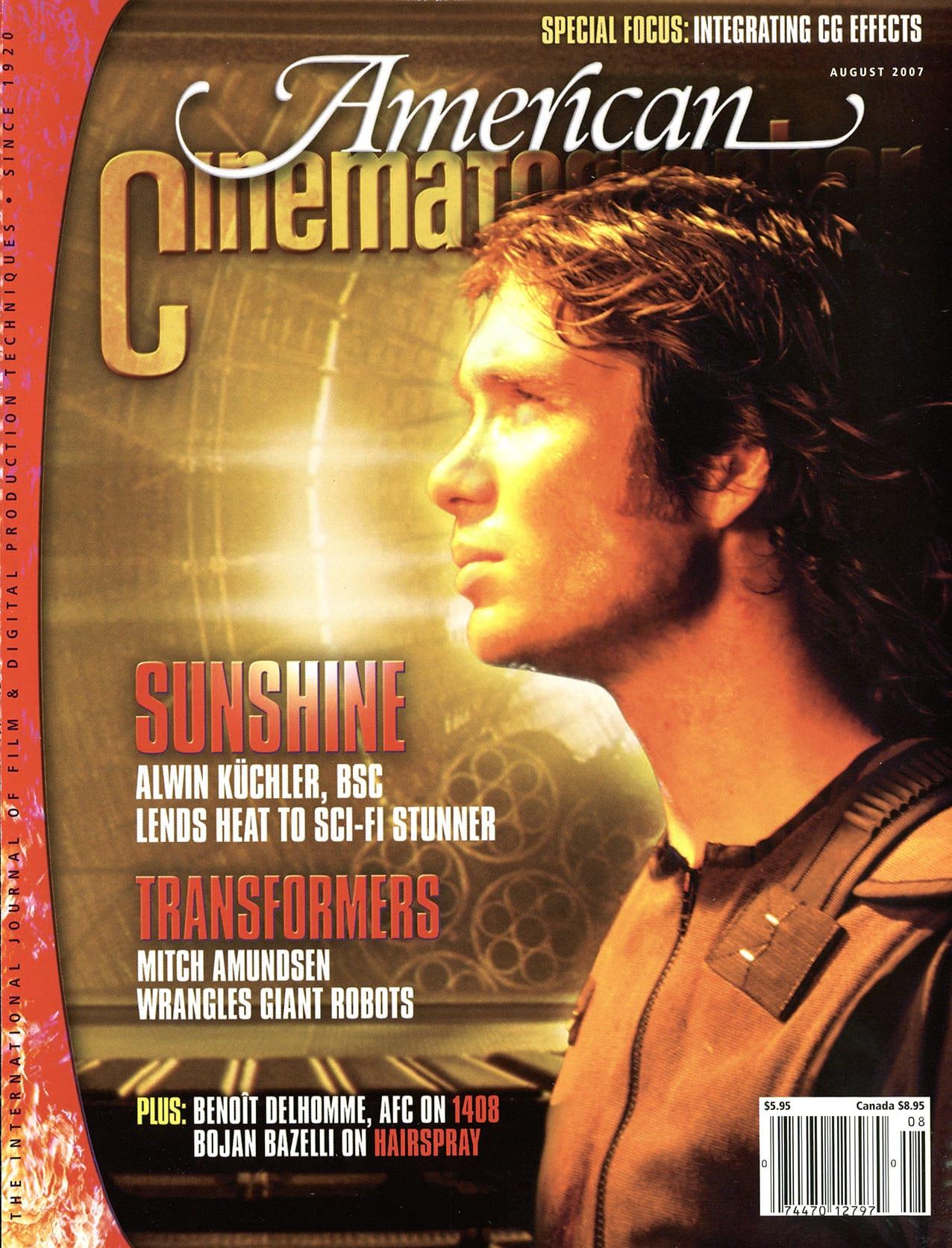

Alwin Küchler, BSC uses three formats and creative visual effects to realize Danny Boyle’s sci-fi thriller, which sends a team of astronauts on a mission to revive the dying sun.

Unit photography by Alex Bailey

The sci-fi drama Sunshine is set 50 years from now, and global warming is no longer a threat. In fact, the sun is dying and the world has started to freeze. In an attempt to reverse its slow fade, a team of scientists has been sent into space aboard the Icarus II with a large nuclear bomb that they hope will reignite the dying star. Capa (Cillian Murphy), the crew’s physicist and the film’s narrator, explains that another crew set out on an identical mission several years earlier and disappeared before reaching their objective.

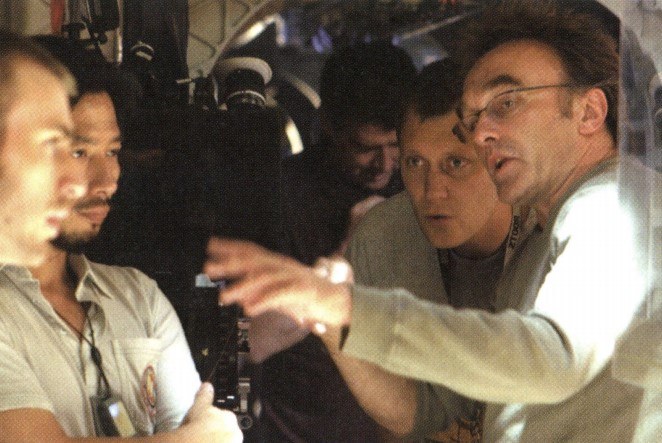

Sunshine marks the first feature collaboration between director Danny Boyle and Alwin Küchler, BSC, whose credits include The Claim (AC March ’01), Code 46 (AC Sept. ’04), The Mother and Proof. A native of Düsseldorf, Germany, who has lived in England since 1989, Küchler worked with Boyle briefly in 2002, when he shot some pickups on 28 Days Later (AC July ’03) for Anthony Dod Mantle, DFF, BSC.

According to Boyle, the first of many challenges the team confronted on Sunshine was how to craft visuals that would differentiate the film from its well-known predecessors. “If you’re going to make a space movie, you’ve got to make something a bit different — you can’t just remake Alien,” says the director.

“Space is infinite but claustrophobic at the same time. There’s no real reprieve — you can’t step outside for a breath of fresh air.”

— director Danny Boyle

“In other genres there’s a lot of terrain to work with, but in space movies you can’t escape tight corridors and little rooms surrounded by metal. And when you’re working in those tight corridors, you’re keenly aware of all the filmmakers who’ve done amazing work before you in the same kind of corridors; you can feel them right there with you, and that challenges you to make your own mark in that corridor for future filmmakers to bump into.”

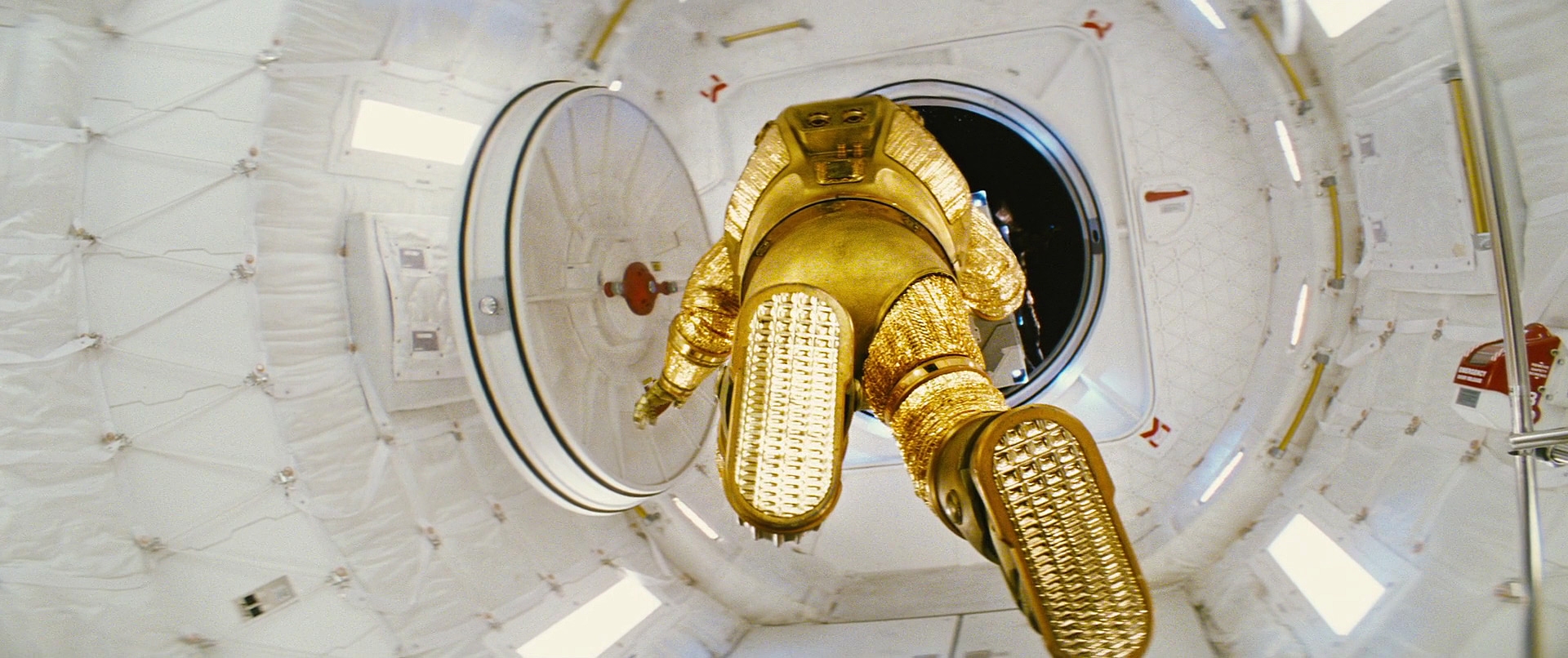

Although Alien was a reference for the filmmakers, the German film Das Boot was more influential, according to Küchler. “That movie really helped us lock onto the idea of a very claustrophobic world and the tension that can arise when a group of people have to share a tight space for a long period of time,” he says. Boyle adds, “Space is infinite but claustrophobic at the same time. There’s no real reprieve — you can’t step outside for a breath of fresh air.” To heighten the sense of claustrophobia aboard the Icarus II, production designer Mark Tildesley built hard ceilings into the sets, and Küchler slowly increased the focal length of the lenses as the story progressed to compress the space further. “Danny wanted to play around with scale,” recalls the cinematographer. “As they approach the sun, the sun takes up more space in each character’s psyche and the tension ratchets up.”

“Mixing formats enabled us to get horizontal flares in interiors and circular flares for all the scenes involving the sun.”

— Alwin Küchler, BSC

Another challenge was “how to sustain a film about light, especially when that light has to become more powerful as the characters get closer to it,” says Boyle. “In a movie theater you can only get so bright, and you can only sustain that kind of white-out brightness for a second or so before the effect is totally lost. We had to very carefully parcel out when the audience was able to go into the light, yet we always had to keep light alive as a character in the film.”

Part of the solution was the use of color. “We had the color police on set every day, making sure that no orange or yellow or red was anywhere in sight,” recalls Boyle. “The film’s gray-blue palette is a convention of space movies; it’s a diet the audience expects. We take it a step further and starve them of any warm colors until they see the sun itself.”

Notes Küchler, “There are certain things you plan, like starving the audience of warm colors to make the visuals of the sun more powerful, but there are some things you just stumble across that almost end up being more important. For example, we started shooting macro close-ups of eyes now and then, and without even talking about it we started shooting more and more of them. We realized the pupil of the eye is like a negative image of the sun itself, and looking into someone’s eye like that is like looking into his soul. You find these abstract images that express a lot, and it’s a lot of fun to discover them.”

To suggest the sun’s presence when it isn’t onscreen, the filmmakers decided to make lens flares a significant player in the visual scheme. “A flare is atoms of light coming into your eyes, a moment when the surface of the screen seems to be broken and things are out of control and the relationship between the audience and the screen is penetrated,” says Boyle. “I became very interested in not just washing the audience with light, but actually reaching out to them, through them, with light.”

Küchler shot anamorphic and Super 35mm to create two different types of flares, using Hawk anamorphic lenses to film the ship’s artificially lit interiors and Zeiss Ultra and Master Primes to film any scenes featuring sunlight (including ship exteriors and interiors such as the observation room). “Mixing formats enabled us to get horizontal flares in interiors and circular flares for all the scenes involving the sun,” says Küchler. “This was my first anamorphic shoot, and I tortured myself for three weeks over which lenses to choose, but in the end the Hawks won, mainly because we wanted to look different than Alien and Event Horizon.”

Küchler’s main cameras were an Arricam Studio, two Arri 435 Xtremes, and an Arri 235, and Arri Munich manufactured a special ground glass that marked a 2.40:1 anamorphic center extraction on the Super 35mm area so he wouldn’t need another camera for anamorphic work. “I tend to favor Arri cameras when I’m dealing with tight spaces because I find Panavision cameras aren’t as advanced in adaptability — you can’t move the viewfinder from one side of the camera to the other, for example, and in tight spaces that can be a lifesaver. We used the 235 in tight spaces and when we had to be very physical and fast, like in the fight scenes where we got into the action.”

The rule on the set was no protection for the lens — no matteboxes, no flags around the lens. Küchler chose lights specifically for their flaring potential, selecting mainly smaller bulbs with small filaments to hit the lens with hard, point sources. “We collected flares like people collect butterflies!” he says. “We collected anything that was interesting and used it when necessary for the right effect.”

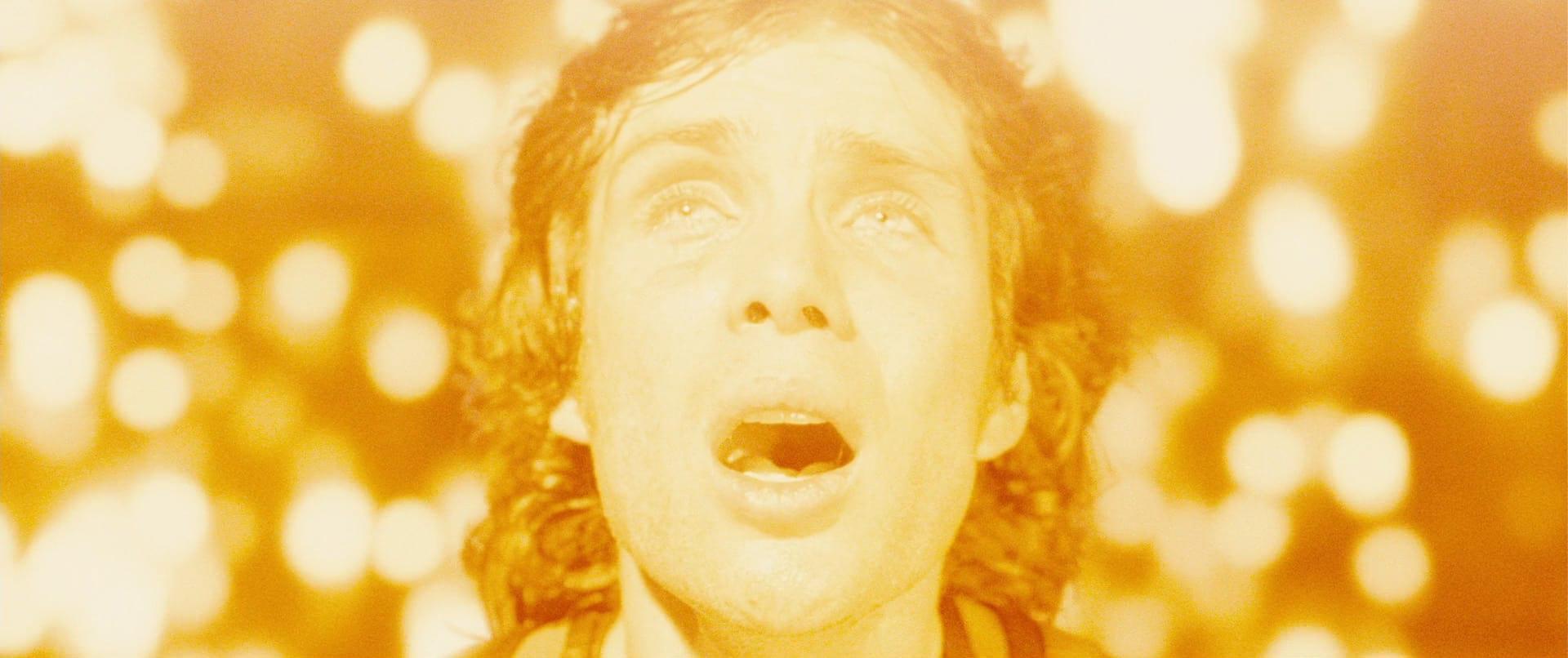

In one scene, Capa awakens from a nightmare in which he is falling to the surface of the sun. Fellow crewmember Cassie (Rose Byrne), the ship’s pilot, is there to commiserate with him. Both actors are shot in singles, and a prominent flare takes up a large portion of the frame in both shots, suggesting Capa’s unsettled mental condition. Küchler created the effect by holding a small, low-voltage Luxeon LED light with a spot lens at the end of a flexible wire and positioning it for the best flare. “At that point in the film, everybody’s consciousness is slightly warped because the presence of the sun has become overwhelming,” he explains. “The flares, the feeling of light out of control, really helped express that feeling.”

Flares were also incorporated into the film’s digital effects, which were created at The Moving Picture Co. (MPC) in London under the direction of visual-effects supervisor Tom Wood. However, most of the flares utilized in the CG elements were real, taken from Küchler’s test footage and from additional flare footage he filmed specifically for Wood’s team. “CG lens flares often look too processed and clean, so I prefer using proper camera flares when possible,” says Wood. “We used almost every flare Alwin had shot in his tests, and when we started to run out of them, he spent a day shooting hundreds of feet of flares specifically for us. He shot all of the flare work on black, so they were incredibly easy to composite into our work.”

Prior to Sunshine, neither Küchler nor Boyle had worked on a CGI-heavy project, and the cinematographer says the experience “was a huge learning curve for both of us. We both felt we should try to do as much as possible in camera and fill in the blanks with CG effects, and Tom Wood agreed. I think the relationship between the cinematographer and the visual-effects supervisor should be just as close as the relationship between the cinematographer and the production designer; everyone brings a different taste, aesthetic and experience to a film, and it’s important that you’re all working from the same philosophy and toward the same goals. With Tom, we were definitely all on the same page.”

Wood adds, “I wanted everything we created to look like something Alwin had shot. Most visual-effects supervisors will say they’re working to achieve the director’s vision, and that’s true, but I think that making it look like the director’s vision shot through the cinematographer’s camera is the key to great effects work.”

The filmmakers used 65mm to achieve one particularly surreal effect. In the scene, volatile crewmember Mace (Chris Evans) is trying to chill out in the “Earth Room,” a virtual-reality environment designed to simulate earthly environments that relax the spectator. Mace appears to be present as massive waves crash into a pier and spray bystanders with water; the scene changes briefly to a forest, then back to the pier (below). “We wanted to give the Earth Room a surreal feel, so we decided to shoot the plates and Chris on 65mm,” says Küchler. “That footage was scanned and integrated into the final film in the digital intermediate [DI].”

During the DI, which was also handled by MPC, most of the footage was scanned at 4K through the Spirit DataCine, but visual-effects sequences were scanned on a Northlight. The 65mm sequences were scanned at 5K and down-rezzed to 2K for integration into the final, which was filmed out on an Arrilaser.

Küchler shot the picture on a single stock, Kodak Vision2 500T 5218, but notes he would have liked another option. “I would have loved to use reversal stock for our most extreme images, but Kodak stopped making its 400 [ISO] reversals,” he laments. “Reversal stock has such a great palette, and it behaves so differently than negative stocks. I tested removing the remjet backing on the emulsion to get a different kind of chemical reaction to highlights, but unfortunately, the insurance companies won’t cover the negative if you do that, so I was left with negative stock. The blessing and curse is that today’s stocks are really good; I could overexpose a scene by 5 or 6 stops and easily bring it back to normal in the digital grade. When we wanted the image to really burn out, I had to overexpose by 8, 9, even 10 stops to really burn the information away to the point where we couldn’t get it back. We wanted to physically attack the stock with light to get the right effect. When Searle [played by Cliff Curtis] is exposed to the sun, that’s 10 stops overexposed, and what you see is literally the only information left on the negative — there’s nothing else there.”

Küchler decided to light the interior of the Icarus II primarily with practical fixtures built into the sets, which were constructed at 3 Mills Studios in London. “About 80 percent of the lighting in the ship is practicals,” says Küchler. “We worked really hard with Mark Tildesley to design the lighting into the set. Most of the sets were so tight there wasn’t any room for us to bring in a 2K or big Kino Flos, so we decided to integrate the lighting and supplement it with small floor instruments when necessary.”

Working with practical-lighting specialist Joe McGee, Küchler and his gaffer, Reuben Garrett, chose a lot of Osram compact fluorescent tubes, which were integrated into custom fixtures and housings throughout the set, as well as a number of hi-tech LED fixtures. “The Osrams have a really high output in a small, low-power fitting,” notes Garrett. “They were built into the ceilings in housings that could be adjusted up and down, and most of them had louver-like eggcrate honeycombs on them to control spill and direct the light. You can get the Osram and Philips bulbs in a range of colors; 930s are tungsten, 940s are around 4500°K, and 950s are daylight. They all have a very high CRI, so there’s no green spike, and they can all be dimmed down to about 30 percent.”

McGee and Garrett hooked all of the fluorescent fixtures into DMX-addressable high-frequency ballasts that all ran back to a Light by Numbers dimmer-control board operated by Stephen Mathie. “Light by Numbers was really important to us,” states Küchler. “We had more than 800 practicals in the set, all individually controlled by that dimmer board.” Garrett adds, “We had all sorts of macros programmed that we could trigger with the press of a button and dim up or down, whatever we needed. It’s fantastic to be able to have the board operator next to you with a little PDA in his hands and have full and immediate control over everything.

“In the walls of the social quarters, we also used long, skinny cathode fixtures, bulbs that were about 1/4-inch in diameter and 14 inches long,” continues Garrett. “We also used a number of the Luxeon 1- and 3-watt LED lights in special fixtures that allowed us to choose the lenses we wanted so we could get some punchy, hot backlights or kicks where needed. Also, Osram makes these great strips of LEDs about 1?4-inch wide with an adhesive backing. We could slap that up anywhere. In prep, Joe McGee gave us a wealth of lights and fixtures to pick from.”

When supplemental lighting was required, Küchler and Garrett used 15" Kino Flos and Kino fixtures lamped with the same compact fluorescent U-tube bulbs used in the practicals, and a smattering of Dedo lights for extra punch. “We often had several actors in a scene and were trying to squeeze three or four of them into each shot, and the floor fixtures helped fill in the gaps and pick out faces,” notes the gaffer. “I have to say we had a great collaboration with Mark Tildesley and his crew. It was a tight partnership that we certainly pushed to the limits in prep. While they were building the set, Alwin and I walked around with a Kino Flo and said, ‘We need a light here, and here, and here …’ and they cut the holes where we needed them.”

Although most of the set is filled with carefully placed soft sources, Küchler occasionally used very hard sources to accentuate the emotions of a scene. “I generally use soft light, but there are times when I want to make something scream a bit. It’s very much like a dissonant chord in music, something that gets into your head. That’s what hard lighting can be. Sometimes you want that hot, noisy light to really punctuate a moment. Sometimes you want it to be ugly because it’s what the scene is about. That’s usually when I turn to harder, hotter lighting.”

Küchler strove to create a delicate balance between bright and dim areas throughout the Icarus II. The ship’s oxygen garden, where masses of plants are grown to produce natural oxygen for the crew, is bright and open, in contrast to the dark and moody bridge. “Some areas in a ship are naturally dark, like the rooms where they need to read lots of instrument panels,” he notes. “Also, the crew of a ship like this would want to conserve energy and not use unnecessary lighting. We felt we couldn’t totally starve the audience of light, of course, but we did try to design periods of darkness before scenes that featured the sun, stretches of maybe 10 minutes or so, so that the light of the sun would be that much more impressive when it appeared.”

The sunlight — or lack thereof — was a significant challenge for Wood and his team on shots of the ship’s exterior. “Usually in space movies, the ship at hand is lit by an apparent solar light source, but in Sunshine the ship is traveling behind a huge shield that protects it from the sun’s intensity,” says Wood. “That took awhile to get our heads around. We had to create a ship that was traveling in the shadow of the universe’s only light source, but, of course, we had to see it. That meant the ship had to be entirely self-illuminated. I took a page out of Alwin’s book and put a lot of little lights on the exterior that we allowed to flare the lens and help fill in the shadows. It continued the visual concept of uncontrolled light that the camera is struggling to cope with, even artificial light generated by the ship itself.

“We had to be very literal in our interpretation of how the sun looked onscreen because it’s our sun,” continues Wood. “There’s a massive amount of footage available, especially from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, which has a satellite that sits between Earth and the sun. We wanted to hold on to familiar images but add less familiar ones, such as gamma radiation views, extreme X-rays and extreme ultraviolet images all combined into a single image. We wanted to create an image of the sun that was familiar but also awe-inspiring.”

Sunshine opens with Searle, the ship’s psychologist, sitting in the observation room looking at the sun (above). We soon learn we’re seeing a highly filtered image of the sun, about 2 percent of its intensity. Searle asks the ship’s computer to dial down the filtration as far as is safe, and he then sees the sun at 3.2 percent of its intensity, which is blindingly bright. “From that point forward,” says Wood, “it’s understood that we’re looking at a manipulated image of the sun throughout the film, a filtered image, even when we’re outside of the ship, so the audience can see detail in sun’s surface, which wouldn’t otherwise be possible.”

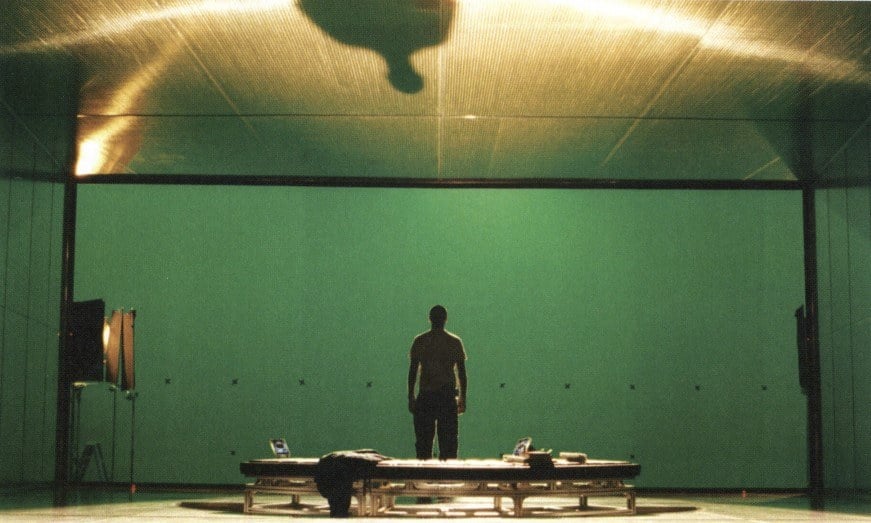

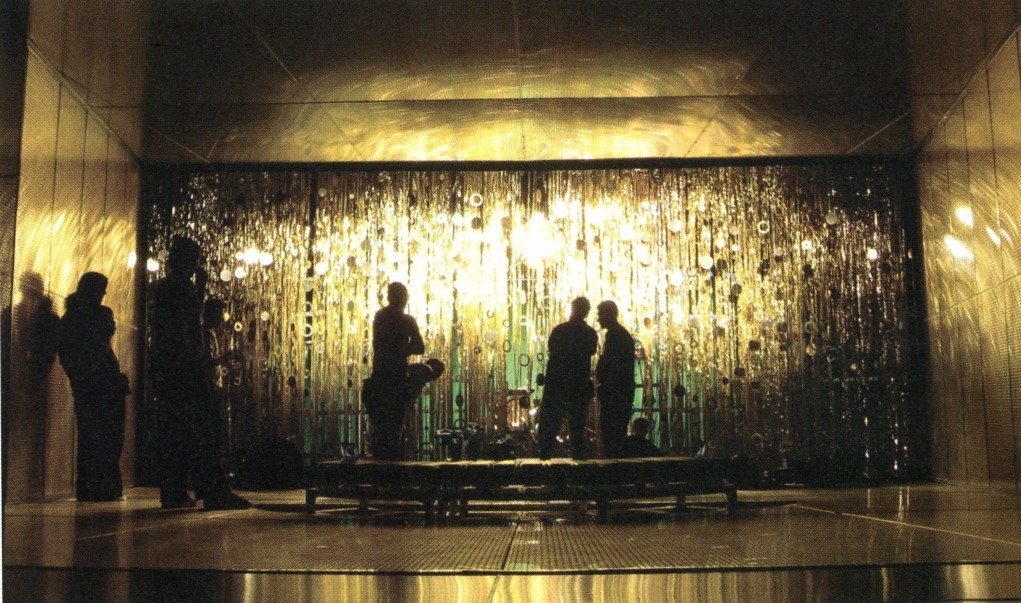

Although some might expect filmmakers to merely bring in a lot of very bright lights to represent the sun, Küchler and Boyle wanted to give the sunlight texture, life and animation. “In the observation room, Danny was nervous about shooting the actors in front of a big greenscreen and not giving them anything to react to when they’re supposed to be experiencing the majesty of the sun,” recalls the cinematographer. Küchler decided to create a large, animated light source that was actually thousands of small lights put together. Early in prep, he had spotted a vendor’s sign made up of hundreds of tiny reflective circles that fluttered in the wind. He decided to integrate this concept into his version of sunlight in the observation room. Garrett recalls, “During testing, we brought in a board covered with tiny reflectors, bounced a light into it and got a lot of movement and individual flares from hundreds of specular reflections. The light seemed to be dancing all around the room, and that was exactly the effect Alwin wanted.”

Creating a large-scale reflector board covered with thousands of miniature reflectors turned out to be too expensive, so Küchler and Garrett had to improvise. They ended up hanging a “disco curtain” made of thin strips of gold Mylar across the front of the observation room, an area 35' high and 60' wide. In front of that, they suspended several hundred gold discs in various sizes on fishing line. They split the curtain in half and then angled the halves at 45° so they could bounce several Dinos into each side, and placed fans on the curtain to flutter the reflections. “We had 10 Dinos on each side and another six across the top, along with a number of Source Four Lekos randomly placed to add extra punch,” details Garrett. “The Dinos were lamped with CP62 medium-spot bulbs and were all on dimmers. For shots when they’re getting really close to the sun, we put a 20K Molebeam in the middle of the curtain and aimed it straight into the observation room through the wall.”

“We dimmed down all the Wendy lights [Dinos] to about 10 percent for normal sun viewing in the room, but when they turn up the brightness, we brought up the lights, and you could really feel the sudden increase in heat in the room,” notes Kuchler. “That certainly gave the actors something real to react to! Having the support of the director for an effect like this was crucial, because it was not cheap.”

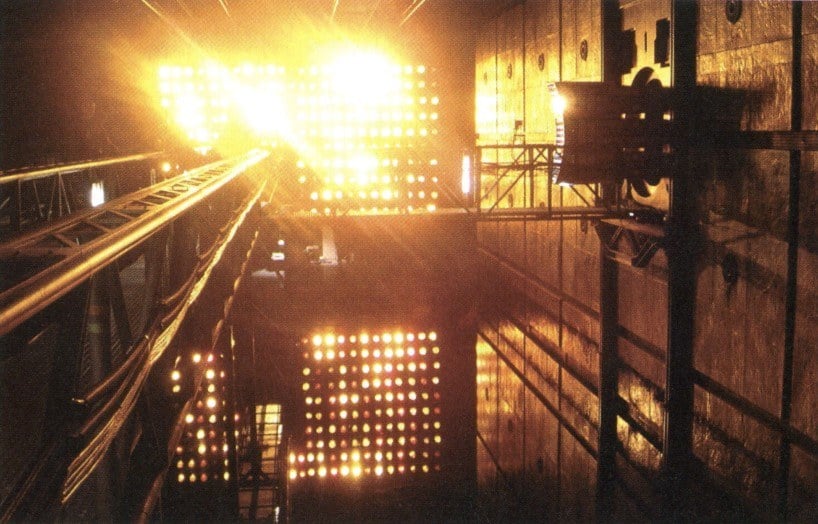

At the end of Sunshine, Capa is on a part of the ship that is suddenly directly exposed to the sun. The walls are literally ripped open and a fireball tears through the ship toward Capa. To achieve this effect, Küchler and Garrett created a 60'-wide traveling rig of 180 Par cans that could be flown at the actor. “We wanted to move a whole wall of light right at Cillian,” says Küchler.

The Par cans were rigged in sets of six on standard Par can bars, then six sets of bars were lined up to create 24 lights across. At its largest point, the rig was 10 Par cans high by 24 wide. The whole grid was suspended on rollers attached to I-beams on the stage’s ceiling. Some of the Par cans were lamped with CP62 medium-spot bulbs, while others were lamped with CP61 spot bulbs. Garrett used a mix of gels — Yellow, Primary Red, and CTO ranging from 1/2 to Double Full — and placed them at random throughout the rig. All of the fixtures were connected to the Light by Numbers dimmer board, and a series of chases was programmed to create a fire effect. The rig itself was cable-controlled and could move at 5-7 mph down its 60' track toward Murphy. “When we moved that massive light closer to Cillian, it would start to wrap around his face and go from a fairly direct source to a very large soft source, and you could feel it traveling toward him like the fireball is supposed to do,” says Garrett.

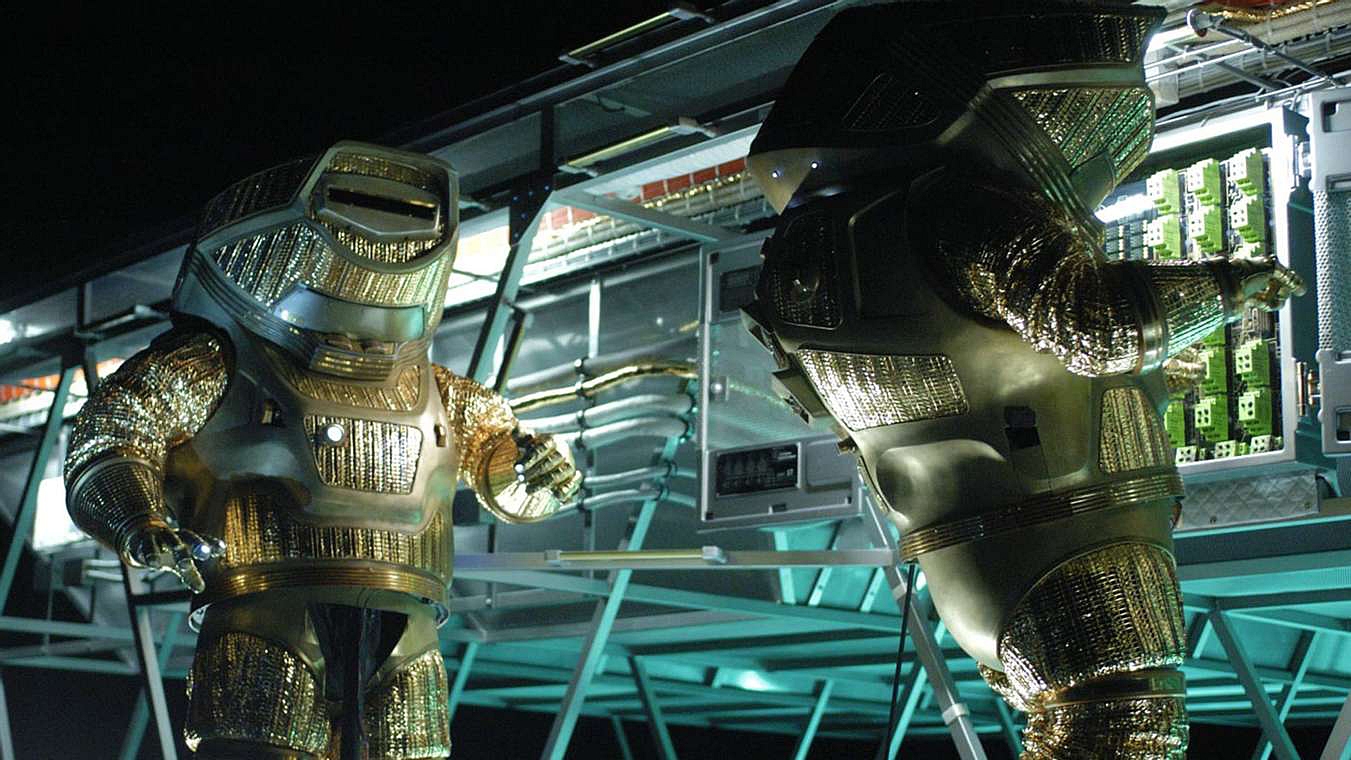

During their mission, the crew comes across the original Icarus still orbiting the sun. Theorizing that two bombs are better than one, they decide to dock with the dead ship and try to obtain the original bomb to double their chances of a successful mission. But the plan is a bust: the ship’s power supply and controls have been destroyed, and there is no means of capturing or controlling the bomb aboard. Upon returning to the Icarus II, the crew discovers a lethal stowaway: Capt. Pinbacker (Mark Strong), the original mission’s only survivor. Having lived alone in close proximity to the sun for seven years, Pinbacker has become something not entirely human, and he is perhaps Sunshine’s most unique and perplexing visual effect — one achieved entirely in camera.

“Pinbacker is a human being, but the forces of light he’s been exposed to have reorganized his protons and neutrons,” says Boyle. “It’s something I’m not sure I can explain. He’s seriously burned by prolonged exposure to the sun, but the light has changed him in other ways as well. Imagine the power the sun has, the energy, and what might be gained by being in close proximity to that power for seven years. He’s not a god, but he has been exposed to the extraordinary. The way he’s seen onscreen represents how the characters see him — they can’t quite focus on him. It’s like trying to stare at the sun for too long.”

Because Pinbacker appears in some two-shots, Küchler had to find a way to create the effect that wouldn’t affect anyone else in the frame. “We did a lot of testing and finally came up with a fairly simple solution: we put a prism in front of the lens to distort the image and manipulated it manually,” he says. He utilized a front-projection beam splitter with a 45° half (50-percent transparent) mirror. On the other side, instead of a projector, Küchler and key grip Adrian McCarthy mounted a second camera so that both cameras would shoot exactly the same image through the aid of the 45° half mirror. Each camera had the same focal-length lens on it, and Küchler handheld Schneider 10" diopters in front of one of the cameras to distort the image of Pinbacker while the second camera remained clean.

“We moved the diopters in and out and twisted them,” explains Kuchler. “The rig was very large — it required two focus pullers and one person operating the diopters, usually me or my loader. Of course, we had to tent in the lenses to avoid any extra reflections on the 45-degree mirror. In addition, Danny wanted to Dutch the shots, but the rig was so big and heavy we actually broke our Dutch head after the first week of working with it! Adrian made a new Dutch head out of an old heavy-duty video head and combined that with our OConnor head; that was the only way to withstand the weight of the rig and get the shots Danny wanted. We used two cameras so the images could be combined later, and Danny could pick and choose when he wanted the effect and where it would fall in the frame.”

“Making a film like Sunshine is a bit like setting out on a journey to the Arctic: you’ve got to have everything you need when you set off because there’s no going back,” says Boyle.

“A film like this takes an incredible amount of preparation and planning. There’s a great quote from John Boorman: ‘Filmmaking is the process of turning money into light.’ Making Sunshine was literally taking all of our lives, and a lot of money, and turning it into light.”

2.40:1 35mm and 65mm

Arricam Studio; Arri 435 Xtreme, 235; Arriflex 765

Hawk Anamorphic; Zeiss Ultra Prime, Master Prime lenses

Kodak Vision2 500T 5218

Digital Intermediate