Family Business: Supernatural

Serge Ladouceur, CSC details how his visual approach to this imaginative, long-running genre series evolved with storytelling tactics and technology, leading to new creative choices.

Unit photography by Sergei Bachlakov, Dean Buscher, Michael Courtney, David Gray, Justin Lubin, Diyah Pera, Jack Rowand and Katie Yu. Images courtesy of The CW/Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All photos ©2020 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Additional images courtesy of Serge Ladouceur, CSC.

Editor’s Note: This is an expanded version of the feature story that appears in the March 2020 edition of AC. Some images are additional or alternate. The series finalé, originally planned to air May 18, was postponed until November 11 due to COVID-19-related delays in production and post.

“We started shooting today,” Supernatural director of photography Serge Ladouceur, CSC told AC on Jan. 7, as the cast and crew resumed production the show’s 15th and final season after a holiday hiatus. “It feels strange to think we’re into our last run.” And what a run it’s been.

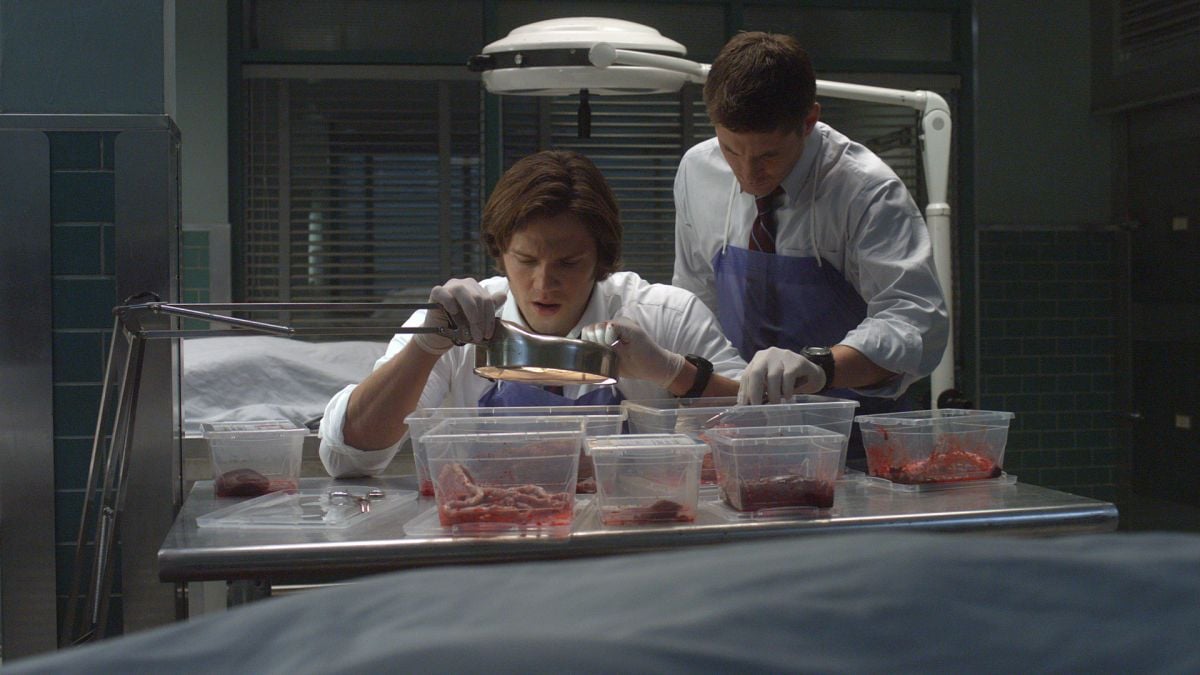

Since the CW series made its debut in 2005, the labyrinthine exploits of intrepid “hunters” Sam and Dean Winchester (played by Jared Padalecki and Jensen Ackles) have seen them repeatedly crisscross the country, as well as journey to both heaven and hell, along with stints in purgatory and alternate dimensions. Throughout, the boys have tangled with and dispatched all manner of inhuman antagonists — a “family business” trade they learned in childhood from their stern father (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) — backed up by the fallen angel Castiel (Misha Collins) and surrogate dad Bobby (Jim Beaver), among many others. But whether confronted by ghosts, ghouls, witches, angels, demons or even God himself, the brothers’ resourcefulness — as well as their jet-black 1967 Chevy Impala lovingly known as “Baby” — saw them through to the next episode. And along for this entire wild ride has been Ladouceur, also a co-producer in the show.

The French-Canadian cinematographer joined the Supernatural family immediately after the show’s dark and spooky pilot was completed in Los Angeles— photographed by Aaron Schneider, ASC — and the production established a permanent home base in Vancouver. There they began an odyssey across 327 episodes, 320 of which were shot by Ladouceur with help from his many invaluable crew people who cycled through the production over the years. Another seven episodes were shot by Bradley S. Creasser, Ladouceur’s longtime A-camera operator, three of which the cinematographer directed, and they split credit on two more.

Initially, Supernatural took key visual cues from the groundbreaking show The X Files — the narrative construction of which it also resembled, as Sam and Dean investigate paranormal activity and even frequently impersonate FBI agents to do so. Yet by embracing the existence of the macabre, the saintly and often the ghastly, the show also developed a distinct elasticity in terms of storytelling, routinely breaking format and often delivering a loving parody or meta, fourth-wall-testing satire on its own existence.

Since the beginning, Supernatural has been shot on stage at the Canadian Motion Picture Park (CMPP) in Burnaby and on location in and around Vancouver, with few standing sets and the ratio of stage-to-location work depending on the needs of the scripts.

Not long after its inception, the show evolved from being distinctly episodic to the serialized story-arc format in vogue today, which brought new creative opportunities to Ladouceur. Supernatural also serves as a case study in the transition to digital production — as the pilot and first three seasons were shot on 35mm film and then captured on a series of increasingly capable digital cinema cameras: the Arri D-21, the Red One Mysterium-X, and ultimately ARRI’s Alexa family. Also, rapid advances in LED lighting and other tools have also made a major impact on the show.

A native of Quebec, Ladouceur studied filmmaking at the London International Film School and later worked his way up from camera assistant to operator, and then from second-unit cinematographer to director of photography. His other credits include the feature La Nuit du Déluge (Night of the Flood; for which he earned a CSC Award and a Genie nomination in 1997), Armistead Maupin’s More (And Further) Tales Of The City; Bonanno: A Godfather’s Story; Rudy: The Rudy Giuliani Story; Mambo Italiano and The Case of the Whitechapel Vampire. The latter brought him an ASC Award nomination in 2003.

Regarding the conclusion of Supernatural, Ladouceur explains, “Peter Roth, president of Warner Brothers Television, and Mark Pedowitz, president of The CW, both said that, as long as the boys — Jared and Jensen — wanted to do the show, we were good to go. But we now know the show is ending, not canceled. And that’s a strong point for me; Supernatural will never have the tag ‘canceled.’ It’s just ending.”

The cinematographer spoke with AC about how he kept his creativity fresh over the course of 15 seasons, how he embraced the show’s digital transition, and much more.

“Let’s take into consideration that nobody knew we were going to last 15 seasons. Again, how can you?”

— Serge Ladouceur, CSC

American Cinematographer: When I began researching the phenomenon that is Supernatural, I found that for many of the key people involved in the show, especially you, the IMDb entries abruptly end — and I realized it was because you’ve all been on Supernatural for 15 years. That’s crazy in this day and age.

Serge Ladouceur, CSC: It is crazy, and I never expected it, because how can you?

Isn’t this the dream situation for anyone who wants to focus on telling a complex story and explore different waves of characters? As well as the outrageous phenomenon that makes up this particular show?

It is a dream situation, you’re right, and it’s not only because the length of time we’ve been on the show. Let’s take into consideration that nobody knew we were going to last 15 seasons. Again, how can you? There are many aspects to the Supernatural series that made it what it was. The duration of the show also provided a space and time to explore the characters as they are going through their lives, but many other aspects came together to create this ideal frame of work that was the production of Supernatural. First of all, there was a vision, and that came from Eric Kripke, who created the characters and set them on their courses. And then there was the implementation of that vision, and this is where Robert Singer, executive producer, comes into play. Bob has been the driving force behind the production, setting up the main elements, writers, production crew and studios. He is also a great director combining lyrical approach and sharp vision. I liked the many challenges he threw at me over the years. He will have done 49 episodes when we shoot the series finalé at the end of March. I owe Bob my job on Supernatural and will be forever grateful to him. Now we are finding ourselves, and I’m finding myself, looking back at all these years.

Well, you’ve all shared this joint life adventure.

Absolutely, but how do you summarize the last 15 years of your life? First, you have to talk about life itself because life happened as we were shooting Supernatural. Jared was 22 when the show started; now he’s 37. And Jensen is turning 42 in March. They’re both married and have three kids each. My son Antoine was 13 when we started the show and is now a man and works in the videogame industry as a level designer. And it tints life as a whole. Lucky, I’m married to a wonderful woman who works in the film industry as an actress first and as a writer-producer now, so besides being my supporter and sometimes my toughest critic, she understands this world with its long hours… and being away. Working on this show was like being in a big family with its moods and pleasures. And I share that with many people on my crew who stayed for the ride. And, yes, we can also talk about the evolution of the characters in that 15-year span, living with them, witnessing their stories, which deepened with time, adding layers upon layers. And this was great on a writing level, because as the seasons passed and more secondary characters were added, it created a mythology and a backstory from which characters could return, even after 10 years.

“What [series creator Eric Kripke] wanted to see were stories where the supernatural would manifest itself in real time and in real life.”

You’re working with a great team of writers and producers who’ve been very creative in keeping the show fresh. And, of course, having steady work is an incredible luxury for any cinematographer these days.

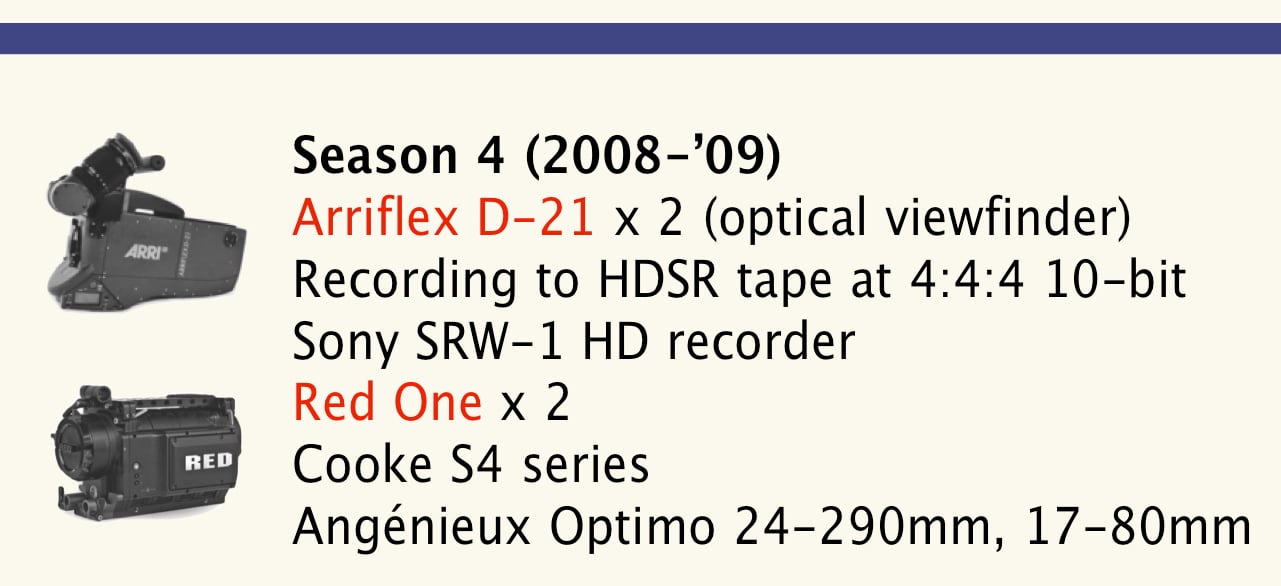

That’s a very good point, yeah. [Laughter] There are many things we can talk about, like the evolution of the style through the changes in formats. We transitioned to digital from 35mm film at the start of Season 4. And then even in digital, we went through different phases, going from the earlier digital cameras — the ARRI D-21 and the Red One — to our current technical state with the ARRI Alexa.

Clearly, your producers always had in their creative vision a show that was dynamic, dark, moody, and expressive. Tell us about the meeting you had early on with series creator Eric Kripke, and how you all found that you were on a similar creative wavelength.

Eric wanted the show to be embedded in reality. He didn’t want to create a fantasy world. What he wanted to see were stories where the supernatural would manifest itself in real time and in real life. This is what he wanted to convey and I was in sync with this concept as I was talking about a naturalistic approach to the lighting. Moreover, and as an example, he was against slow-motion. He didn’t want to beautify the fights by camera techniques. Even to this day we sometimes ask ourselves, “What would Eric want?” And that’s one thing.

Do you feel that sort of outlook has continued fairly consistently throughout the entire run of the show?

It has stayed with us, but rules are meant to be broken, so sometimes it was good to do that. Talking about camera speed, sometimes we would shoot, let’s say, at 96 or 120 frames per second, and use it to ramp in post, having a piece of the action going faster, and then slowing down for a beat. So, in that regard, yes, we did some slow-motion and in-camera tampering with the action.

When you look back, what kept you with the show instead of going off to do something else?

For the first five seasons, there was no real question about staying or going. I was happy to be there, because the mood that was created by the producers, the crew, and the boys, Jensen, Jared, and Misha from the start of Season 4, was very good. Also, the photographic challenges kept coming. Digging into the reasons, I think a good part was due to the fact that there were no standing sets at first and for many seasons, although [father figure monster hunter] Bobby Singer’s house was a set that we went back to many times. That kept the show on a constant discovery path with new looks and new environments to photograph. Even timelines were part of the changing nature of the show with the time-travel episodes. And that’s what I liked and thrived on. Eric Kripke had a story arc for five seasons. At the end of the Season 5, Eric said, “This is it for me, I’ve told the story I wanted to tell and this is it. If somebody else wants to carry the torch, so be it.” And that’s what happened. Sera Gamble became the showrunner for two seasons. Jeremy Carver and Andrew Dabb were the subsequent showrunners. At the end of Season 5, I wasn’t readily stating my interest to keep going. Not at all because I was bored, but when you’ve been on a show for five seasons and there is a dramatic arc that concludes, it was the right moment to ask myself if I wanted to carry on. Also, when I read the script to the Season 5 finalé episode, I thought: “That could be it for me, this is a nice wrap-up, and I could go do something else.” But then, Eric Kripke and Robert Singer had me on the phone from L.A., and they said, “We’re coming back next season, and we’d like you to stay.” So I stayed. And then, after each season, I asked myself the same question, “Should I stay or should I go?” And I kept staying, because of the challenges the show kept bringing, because of the spirit within the crew, because of the feeling I had more and more that I would like to see this show to its end. Which we are now at. A little longer than I expected! That’s what kept me there, the everlasting novelty, the differences that each day brought. And, I should add, the freedom to create and to sometimes go off-script.

“Supernatural was a show that didn’t take itself seriously, but we were doing it seriously.”

Regarding standing sets in those early seasons, there was always the cheap motel that the brothers would find on the road. [Laughs]

There’s always a motel, yes, but since Season 8, there was the Men of Letters headquarters set, which became Sam and Dean’s base, and we kept going back there. We’ve done a lot in the Men of Letters bunker; it’s our only standing set. I have to say, the art department, with our production designer Jerry Wanek, kept producing beautiful, interesting sets and transformed locations. I feel blessed to have had that complicity with Jerry.

Even after the show started changing toward a serialized story format, it seems the writers and producers consistently created episodes that were completely out of left field. For example, “Monster Movie” from Season 4, in which you did a black-and-white episode, and played with all the tropes of Universal horror movies.

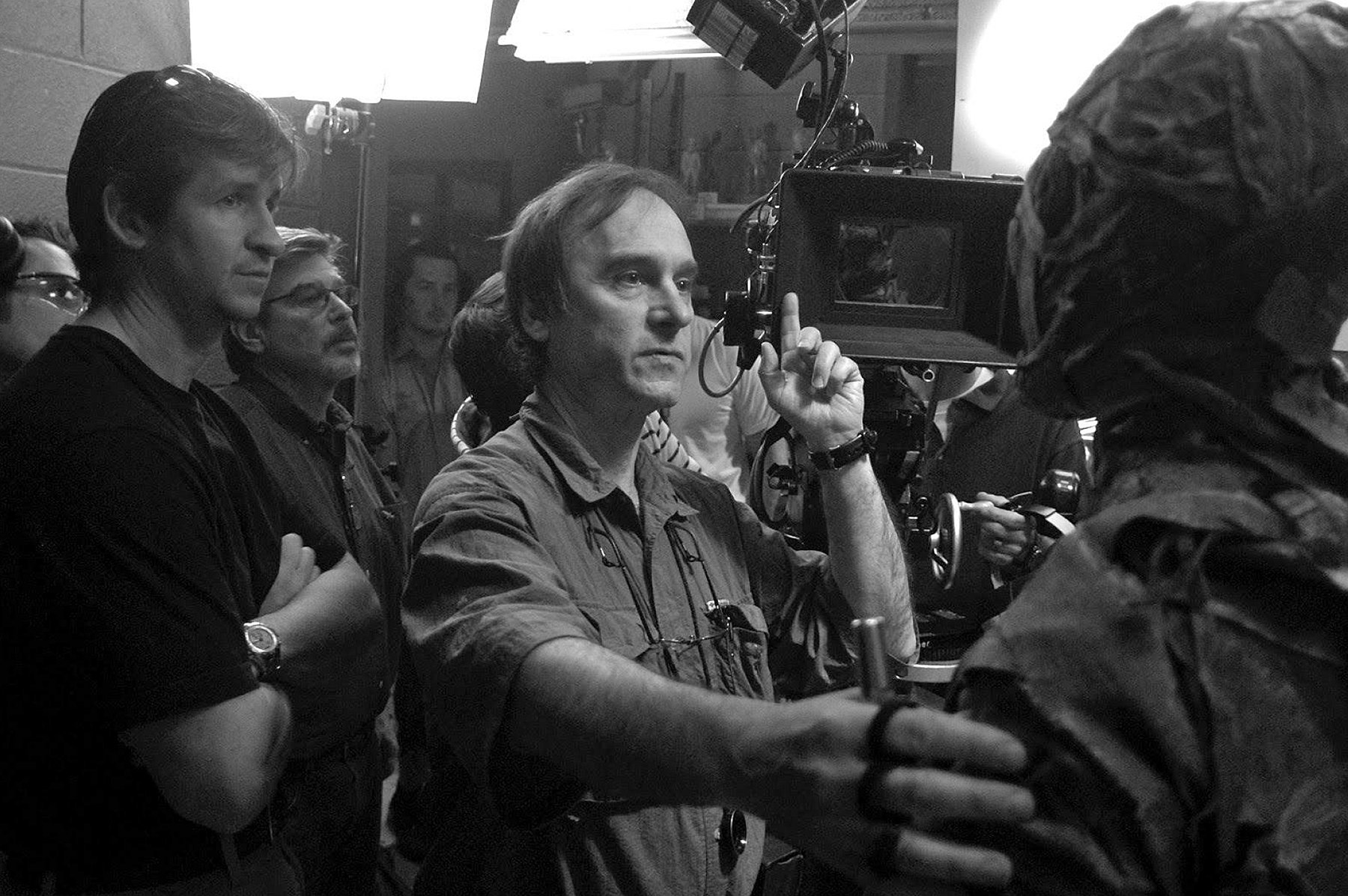

“Monster Movie,” what a treat! Robert Singer directed it and we had a ball doing that episode. I was emulating the look of [Eastman] Plus X 5231 — sadly discontinued in 2010 — aiming to have as little grain as possible. We were in our first episodes after transitioning from film and that episode was shot with the ARRI D-21.

There are lots of other format-breaking episodes, such as the Groundhog Day-inspired episode “Mystery Spot” from Season 3, in which Sam watches Dean repeatedly die hundreds of times in various ways all the while trying to figure why he’s being killed and who’s doing it.

“Mystery Spot,” that’s way back, yeah. A Kim Manners-directed episode.

Way back. That must have been a huge challenge when shooting the same scenes and action over and over again, and doing it in an interesting, engaging way that keeps it fresh so the audience remains interested. And then, in Season 14, the show went to the extreme of doing a fully animated episode with “Scoobynatural,” again making fun of itself and having fun with the horror genre by transporting Sam and Dean into the cartoon realm of Scooby-Doo. And then, “The French Mistake,” which played with the whole nature of television production in a very meta way, with the boys in a parallel universe inhabiting the bodies of actors “Jensen Ackles” and “Jared Padalecki,” making a TV show called Supernatural. So having serialized episodes and then those special episodes sprinkled throughout must be a great opportunity for your cast and crew to refresh your creativity.

Totally, not only because it brought new challenges, but it was a way to keep it interesting. Supernatural was a show that didn’t take itself seriously, but we were doing it seriously.

After the first few seasons of the show, you stopped taking on other projects during the hiatus. Why was that, and can you speak to the need of taking time to recharge your creative batteries?

For me, it was imperative to take that time off, outside of the production “cocoon” existence. That time is not just to recharge the creative batteries, which it does, but to reconnect with life and with my family, my wife, and my son — who is now married. They are in Montreal; I’m in Vancouver shooting. That means a lot of phone calls and Facetime. Even with a second home in Vancouver, the time off is very important and essential. Only once did I take a project during a hiatus. It was between Season 1 and Season 2. It was not clear if Supernatural was going to be picked up, so I did shoot a Canada/UK co-production miniseries that wrapped up in France four days before the start of Season 2. It was a good and interesting project, but I did not do that again because, from that point on, pickups were always announced relatively early.

It must be a challenge to find something as fulfilling as being on show that’s so long-lasting. When I’ve mentioned to people that we’re doing this story, and how many episodes you’ve shot, they stop and say, “Wait a minute… How many episodes?” [Laughs.] Nobody can believe it. They were like, “What? What?!” It’s very unusual.

Sometimes I even have difficulty believing it myself. But we took the time to do it: 15 years! I didn’t photograph all of them though, first of all because there are three episodes I directed, so I didn’t shoot those, plus the ones that were being shot during my preps. To shoot these episodes, we upgraded Bradley Creasser, my A-camera operator, to DP. Brad, who is a very talented and skilled operator, fills in for me when I’m not there — going on survey days, for example. And he also does the 2nd and insert units. So, all together, Brad shot seven episodes, plus we share the credit on two. All in all, I will have shot 320 episodes by the time we wrap.

You briefly mentioned standing sets, and things that would be consistent and you could rely on, a sort of a go-to. And one standing set that you have had, since the very first episode, is the Impala.

You’re absolutely right about the Impala being a standing set.

“At times, to me, [the Impala] became this privileged space for the characters, outside of the time and space of the story, where raw emotions played out, sometimes in the effect of a confessional, or a psychiatrist’s couch.”

There’s so much dialogue and screen time that takes place in the Impala. What was your general approach to using the car to the best effect?

The Impala was kind of the boys’ home until they discovered the Men of Letters bunker [in Season 8]. But over the years the car, “Baby,” has been more than The Car. At times, to me, it became this privileged space for the characters, outside of the time and space of the story, where raw emotions played out, sometimes in the effect of a confessional, or a psychiatrist’s couch. In that sense, the car never lost its meaning as a metaphorical space. In my mind, the current look of our Poor Man’s Process scenes reflect that notion:

So how did shooting in the car evolve? Clearly some of it was on the road, some of it is Poor Man’s Process in the studio, and a small portion of it is greenscreen.

We didn’t do much greenscreen with the Impala. The scenes we did that way were in Season 1 — sending a crew to film plate shots and compositing in post. We went through that process for some episodes, but because of the visual effects costs with outside vendors, the production went another way. Since Season 2, we have had a full-on visual effects department that’s part of the production, so every visual effect is done in-house. It was very convenient to have the visual effect department right here by our stages, so if last-minute questions arose, our VFX supervisor, Mark Meloche, is close by to answer these questions and guide us into the process, on top of having a VFX department representative on set for the days we deal with those shots. Mark was a great asset on Supernatural, having been on the show for its whole duration. He started with the team as the lead artist and then became the VFX supervisor in Season 8, after the departure of Ivan Hayden.

Going back to the Impala, in regard to our PMP, it took a few episodes to really set the approach and the look for the car, which was then developed and improved over the years. One note here: PMP to me works when the car travels in the countryside. It doesn’t work for a city look if you want to create a sense of environment; seeing through the windows. For our city look, I was always pushing for practical shooting, whether on a process trailer or free driving. So that’s why the PMP shots are almost always cut with countryside shots at night.

To talk about the technique itself, we started with basic Poor Man’s Process, like rotating lights, people dressed in black carrying little flashlights at the back of the car for the front shots to create following headlights, or on the side through slats to again create far-away lights from houses or streetlights. This approach can be very rewarding in terms of conveying the effect of a car movement through the night when you embrace the notion and put your heart into it. It’s the land of imagination. Then we started mechanizing some of the process. For instance, we built a rig that we call the “Highways” for our side or profile shots:

Those are two big devices, 20' long each, with two wheels carrying conveyor belts, to which we’ve attached little battery-powered LED lights that go past slats of cut-out black material to create the impression of the car moving. When we designed that, I wanted that one wheel goes a little faster than the other, in order to create the impression of distance; the farther the lights are in the background the slower they would appear to move. That was the idea.

Driving scenes take up a considerable amount of screen time in certain episodes, so it must have been worth the investment.

Yes. When we started discussing that with production manager Craig Matheson and producer Jim Michaels, both saw the benefits and said, “Okay, because we spend a lot of screen time in these scenes, let’s do this.” So, we built one, and then after experiencing shooting with one Highway rig, I said it would be great to have another one in order to cover more angles on a two-camera shoot. The response from the production was: “Okay, we’ll go for another one.” It was great to have that understanding and commitment from the production.

Did that process change after you made the transition to digital?

It didn’t change much as far as the PMP is concerned. What we started doing on film we carried it through our transition to digital. But going digital opened up a range of possibilities in terms of playing with the Impala. We started to go outside at night and free drive, meaning not on a process trailer and with very minimal lighting. Because the Alexa’s response to low light is so great, you don’t need much light outside at night to create an image, provided there are streetlights, city lighting, or some other available source.

Was this just in terms of seeing backgrounds or did this include your lighting for the actors?

A few times we did go out at night with the actors doing free drive on a secured road, using minimal lighting, like strips of LEDs. We would then shoot French overs and side shots from within the car, or from a hostess tray attached to the side window. For these setups, we had a follow van with our monitors and iris control so the director, me and the script supervisor could watch the take from 20' to 50' back. The first AC would be either in the car or in the following vehicle with remote focus.

What about getting long-shot B-roll of the Impala driving in various conditions? It’s very important connective material throughout the show.

As far as B-roll of the car is concerned, Phil Sgriccia, who was an executive producer and in charge of postproduction up to Season 14, went out in the country a few times with a small crew, and for two or three days, they would shoot B-roll. They shot night and day shots, multiple angles, with photo doubles. He created a bank of footage that the editors could go to whenever they needed a shot of the Impala on the road. Whenever we had the car driving into the distance, those were the shots he gathered during these expeditions. On main unit, we were still shooting some specific shots with the Impala, but these ones that Phil gathered proved to be very useful. Phil is also a wonderful director who did 45 episodes, always pushing to explore new ways of portraying the stories.

“The concept [of the episode ‘Baby’] was that the camera would never leave the Impala and the whole story would be told from the point of view of the car.”

And then there is the episode “Baby,” from Season 11, which was shot almost entirely from a POV within the Impala.

Yes, and what a great episode that one is. It was directed by Thomas J. Wright, who did 18 episodes over the years. The concept was that the camera would never leave the Impala and the whole story would be told from the point of view of the car. So we rigged the Impala with sometimes as many as four cameras at a time. They were small cameras, like Canon 5Ds, the Sony a7 III, and our Alexa Mini as well. And then we sent it on the road with the actors in a free-drive mode. Safety was our priority and we had full control of the road where we were filming. It was a challenging, exciting shoot. We shot in the middle of August and it was mostly sunny, a challenge in itself, but at least the sun was constant.

So, early on, your primary standing sets were the motel room and the Impala.

Yeah the motels! But they were never the same, always different. Jerry Wanek created so many motels rooms that they became a sort of anthology of Americana imageries. The final count — as we are filming episode 1516, “Drag Me Away (From You)” — is 176 different motel or hotel sets. All convey an idea or a flavor of America — all beautiful in their own and particular way.

Would the Impala and the motels serve as your cover sets for when you had inclement weather, or…?

There was never a cover set, really. If it was raining, it was raining. Only three times over the years did we change the schedule because it was imperative that the weather be good. We embraced the rain, the snow, the winds, dealing with whatever was thrown at us. On tech surveys, though, I would often ask to change the order of the scenes to benefit for a better position of the sun, for example. But, basically, we never altered the projected scheduling in terms of days. Nonetheless, I can tell you about one major change we made.

When we were prepping the Season 2 finalé, the climax scene with the Yellow-Eyed Demon [Fredric Lehne] and John Winchester [Jeffrey Dean Morgan] was going to be shot outside at night on a cemetery set. The projected weather was going to be so nasty and difficult that the production decided to create the cemetery on stage. It was a big undertaking, but it helped to counter the weather. In general, the Vancouver weather is very particular. Most of the time, and I’m talking mainly about the fall and winter months, you have this beautiful overcast — although drizzly and rainy at times — that was very beneficial to the look of the show. The summer months are mostly sunny and it’s a different approach. I try to avoid direct sunlight on the actors, favoring backlit shots and covering them with a ¼ or full grid cloth in direct sunlight.

Tell me a little bit about the collaboration you’ve had with your location manager or location scouts for the show. Especially, since you’ve been in the Vancouver area for so long, now, it’s got to be a continual challenge to find interesting locations that you’ve not already used.

Yes, indeed, but they keep finding nice locations, and even now, in Season 15, we’re going to places we’ve never been before. What we call the Lower Mainland, which Vancouver is a part of, has a lot to offer in terms of the variety of natural, countryside and city landscapes. I’m not involved in the scouts, but Jerry Wanek, production designer, would often come to me and say, “What do you think of this? I’m thinking of doing that.” “What do you think if we’re going in that kind of location?” We kept this conversation going and it had been a very good relationship.

What about your approach in prep?

Since I’m shooting every episode and not part of the actual prep, I have to get advance warnings of special situations. And for that, my rigging gaffer, Michael Mayo, who’s been with me since Season 3, and who’s constantly on the prep side, has been great for keeping me posted on the upcoming challenges. Michael has been an invaluable asset on the ongoing shooting of Supernatural. By being constantly occupied with prep, he would come to me with layouts of lighting plans he thought would suit me for a set or a location, and then we would discuss it. And I have the same thing to say about David Neveaux, who has been with me all along as rigging key grip. Those two were the backbones of the shooting process of Supernatural. Sometimes, though, I would leave the set to Brad, to fill in as DP, and go on the tech survey for the next episode so I could see things for myself. I prefer that, but I sometimes find myself torn between staying on set because of a special lighting situation or going on the tech survey. For the times I found myself not going, I relied on my gaffer and key grip to survey the work ahead and plan for it. We’ve been working for so long together that they know my ways and what I would like. I trust my guys to do a good prep because often I would arrive in a location, and that’s the first time I’ve seen it. And if I wanted to make a last-minute change, I could, again, rely on the rigging crew to make these adjustments. All that made it possible for me to be constantly shooting, as opposed to alternating episodes with another DP.

Over the years, what’s been your retention rate in terms of your crew? How much of your crew has been with you since the beginning of the show? Have you been able to keep much of the team together?

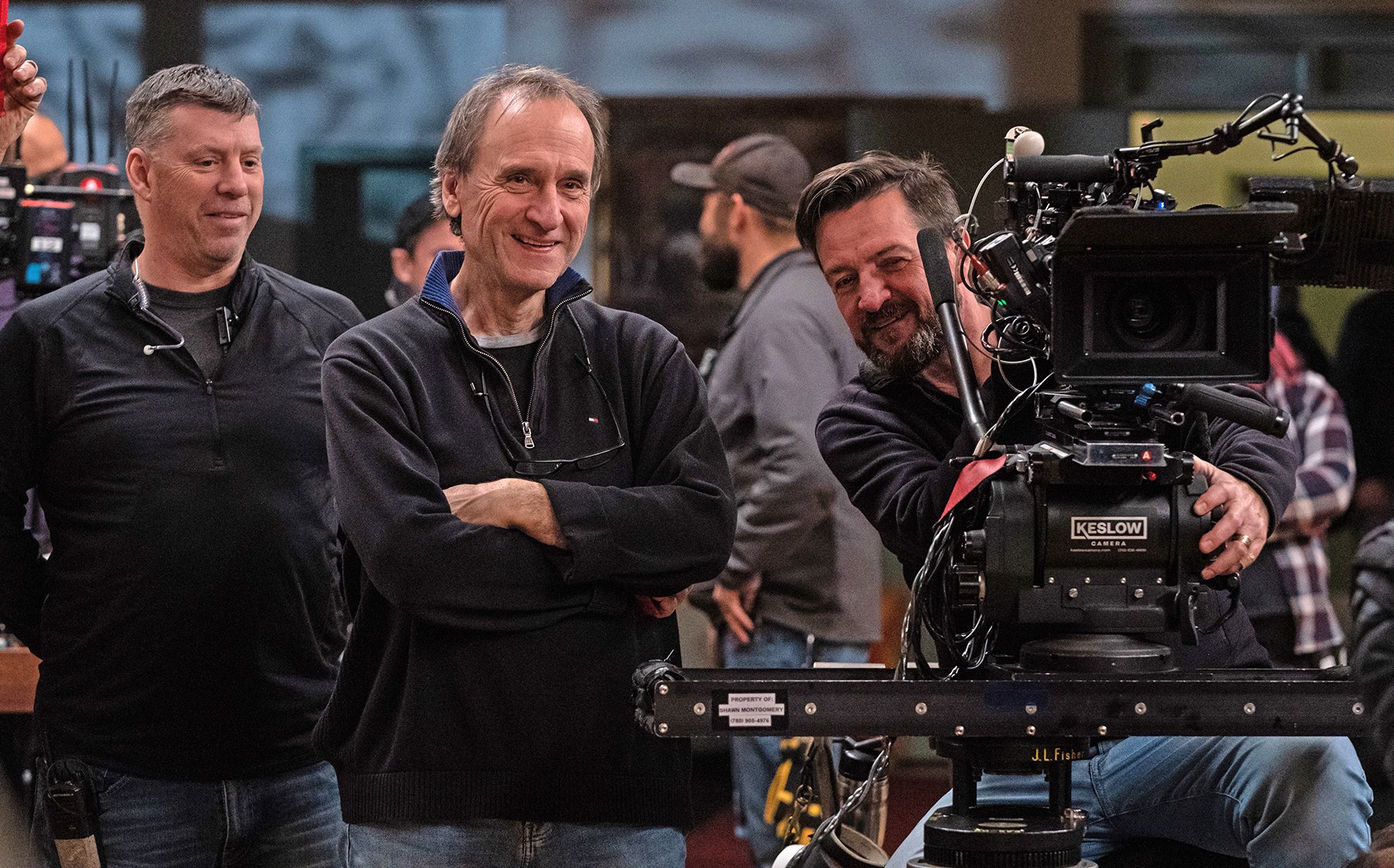

Yes, pretty much. My gaffer, Chris Cochrane, has been there the whole time. My first key grip, Harvey Fedor, was with me until Season 13. After that, Peter Grotek carried the torch for two years, and now I have James Vinblad, who came on board in Season 14. On the camera side, Bradley Creasser, A-camera operator, has been with me since episode 14 of Season 1. Matt Tichenor was my A camera 1stAC up to Season 13 when he left to pursue his career as an operator. Tim Monayan and Brian Rose were 2ndcamera and Steadicam operators for many years. Right now, I have Robin Forst as 2ndcamera and Steadicam operator. Robin had first worked with us on Season 4 and came back after a 10-year hiatus, he joked. Other members of the camera crew are Peter Hunter, 2nd AC with upgrades to 1stAC; Jose Manzano, who started as a 2ndAC and who’s now 1stAC with upgrades to operating and Steadicam; and Clayton Bachynsky, 1stAC on B camera since Season 10. More recently, Christian Cretu and Pierre Cabrejo-Jones joined the team as 2nd AC. My DIT from Season 4 to 13 was Ray Wong, whom I have to credit with the implementation and the smooth running of all the digital systems from Season 4’s tethered D-21 cameras to our current four-camera Alexa Mini package. My current DIT is Jason Haycock, who had been around the show for a long time, starting as 2ndunit DIT. Over the years, we had many camera technicians come to work with us — some as trainees who came back on later as a 2nd AC or crane tech, for example.

After making the transition to digital in Season 4, how did you take advantage of being able to shoot at higher ISOs than you could on film?

At the time we transitioned from 35mm to digital, the cameras were not faster in terms of ISO than what we had with film. The ARRI D-21 was 320 ISO in reality — not ultra-fast. I was rating it at 400 ISO, though. On film, the fastest stock I was using was Kodak Vision3 5219, 500 ISO, with a push of one stop always conveniently available without much added grain.

And you were using the Red One for night work in Season 4?

One of the reasons I chose to add the Red One to our camera package was because the D-21 was a relatively heavy camera for Steadicam and handheld work — not impossible, but heavy. Also, the D-21 was tethered, and I wanted to have a camera that was autonomous. The original Red One was 320 ISO, the same as the D-21, but, on our second year of using the Red, the new MX sensor had a sensitivity of 800 ISO. That’s when I started dedicating more scenes to the Red, [specifically for] our night exteriors and low-light interiors. But I was eyeing the Alexa, which was in the making and was to be ready for Season 6. The release of the Alexa took a little longer, though, and the demand for these cameras was so huge that it wasn’t until the Christmas break of Season 6 that we could make the change. So we completed Season 6 with three Alexas. “The French Mistake” was the first episode we shot entirely with them. For subsequent seasons, we had four Alexa EVs. When the Alexa Mini became available, we swapped one of our EVs to a Mini, and eventually transitioned to four Minis by Season 14. This is the best camera package in terms of flexibility.

After that progression, how did having the option to shoot at higher ISOs with the Mini make a difference?

I set the Alexas at 800 ISO and go from there. There are other ways to improve the performance of the cameras if I want, apart from pushing the sensor to 1,000, 1,200 or 1,600 ISO: I can play with the shutter angle in a way I could not with a film camera. In a film camera, the limit is a 180-degree shutter, but with the Alexas — and other digital cameras — you can go all the way to open shutter. I do not like open shutter, as it adds more blur to the image, but I would go to a 270- or 300-degree shutter to gain an extra 1/2 or 2/3 of a stop, if needed, bringing the theoretical ISO of the camera close to 1,200. I have used this with earlier, less-sensitive cameras, and I still use it today when I want to use the benefits of existing practical lights on locations, or on night exteriors where I would not use extra lighting to bring the background to life, for instance.

“When we switched to digital, I wanted to keep the same look and make the transition from film as seamless as possible.”

How does that in any way change your use of lenses?

When we switched to digital, I wanted to keep the same look and make the transition from film as seamless as possible. To achieve this, I went to a camera system that would be similar in terms of sensor size to a 35mm film negative, and kept the same lens package. Keeping the same depth of field was important to me. A smaller sensor size with a greater depth of field would not cut it. I stayed with Cooke S4s until Season 12, when I switched to Cooke S5s, to dig more in low light with the T1.4 lenses, but keeping the S4 lenses that were not included in the S5 series, namely the 14mm, 21mm, 27mm and 180mm. I also had the Angénieux 12-290mm (T2.8) and 17-80mm (T2.2). The Angénieux zooms, although a little warmer, are great lenses and a good match to the Cookes. Also, we started carrying a Century Periscope [T4.0] all the time for extreme low-angle shots. With our four cameras, it’s a bit of a package for a feature, when you look at it.

In terms of camera and lenses, who supported the production over the years, from film through the digital transition?

Clairmont Camera was our equipment provider from the start until August 2017, when the company was bought by Keslow Camera. The outstanding service that we had for all these years with Clairmont was carried with the new owner. When the options were flying in regards to the transition to digital in 2008, I had the full support of Denny Clairmont. At the time, Denny was watching the development of the Red One camera, and when I told him that I wanted to include it in my package, he jumped in with me and I was then able to combine it with the D-21. He put his facilities and resources behind my choices. I always felt supported and encouraged. Robert Keslow has the same dedication as Denny Clairmont and whenever I had a special request, it was fulfilled with the same enthusiasm. On the grip-electric side of things, besides gaffer Chris Cochrane and rigging gaffer Michael Mayo — who own equipment — we would deal with Sim in Vancouver.

How do you approach shooting with multiple cameras?

Basically, we shoot two cameras, unless for special days when we hire a third operator. Having four cameras makes it possible to have the A and B ready for studio mode on dollies, the C camera handheld-ready, and the D camera Steadicam-ready. In stunt situations, we would often set up a third camera in a lock-off position to grab an extra angle. That saves a lot of time. If we have a crane or Technocrane day, one camera goes to the crane while we operate with the others. So, you know, they don’t wait for us. [Laughter]

How many days would you generally have to shoot an episode?

Eight days, with an occasional 2nd-unit day. It is fast-paced, but in line with the schedules of other series that have similar production patterns. Sometimes, at the prep level when there is an appearance of a crunch in terms of feasibility, things get worked out with everyone involved, writers, executive producers, first ADs, stunt coordinator, visual effects supervisor, etc… So when we go to camera, we are shooting a realistic script. I have to mention one thing here: the producers have made a point early on to cap our days at 14 hours. Most of the time we do 11, 12, 13, sometimes 10, but we are not allowed to go beyond 14. So there were no 15, 16, 17-hour days on Supernatural. And that was one aspect of shooting on Supernatural that made it a production people liked to work on.

One of your other key people is your colorist at Technicolor, Steven Arckle.

Yes, Steven Arckle — whom we call “Sparkle” — has been with the show since the very beginning and he works out of Technicolor in L.A. The most important thing for me is to transmit my detailed intentions to him so he can finesse the images. If a scene has a blue-green bias, for example, or warm or cool, it will be baked into the dailies. He will see that and will know what I’m after. Technically, it's simple in a way. We record the images in Log C QuickTime ProRes clips in the Alexa. On set, we get a Log camera signal, to which we apply a base LUT. Initially, we used the [FilmLight] TrueLight system for coloring from Season 8 through 11. Season 12 and beyond we moved to FSI Box I/O and Teradek COLRs with [Pomfort] LiveGrade software to create our Color Decision List [CDL].

Our recipe with LUT and CDLs applied at Technicolor creates the dailies and transmits them to editing, and from editing the material goes to color timing [which he performs with Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve]. The important point is to leave Steven with enough latitude in the color timing. To make this possible, and make his job easier, we agreed to a set of parameters early on during production. For example, the black and white levels: I don’t go to extremes, no blacks under four divisions and no whites over the 100 mark unless it’s clear I don’t want details in this region. This is where my DIT comes into play and makes sure we abide by these “rules.”

Steven will later push the envelope for me in color timing. Also, I don’t do any iris pulls unless it’s critical. In a situation where I would do an iris pull, I will rather set the T stop in between and let him do the pull — or the dynamic — in the bay. Rather quickly, we came to an understanding about the look of the show, the level of contrast and the color treatment. For a few seasons at the beginning of the show, I used to go to LA around September and sit with him to review the first episodes of a new season before the show began to air in October. Starting shooting in July left us with time to do just that. But we got to a point where we’d been doing it for so long that I didn’t need to be on his back. Once I see the online of an episode — and if I think some scenes needed to be particularly addressed — I’d simply send him notes by email. I miss these color timing sessions though, especially with Steven, but on a fast-paced series like Supernatural, and because I’m doing every episode, I just do not have the time.

How did you establish the initial look of the show once it went to series?

I wanted to experiment with a bleach-bypass look, but applied digitally, an emulation of that photochemical process. I liked it very much at the time. Steven right away was on board with me because there was nothing similar at the time, although The X-Files ventured somehow into this concept years before. Bleach bypass, or silver retention, is the lab process by which exposure latitude and saturation are reduced, and I thought it would be appropriate for the look of Supernatural: desaturated, contrasty, blown-out whites, deep shadows, Gothic!

“We should go back toward what we had, because this is the look of the show, this is what we’re all about, darkness and shadows.”

As you describe that, there’s an episode in the first season, “Wendigo,” that’s a perfect example of...

Yes, that’s the first episode we shot after the pilot.

There were all these wonderful daylight exteriors in the woods, as Sam and Dean search for missing campers who have been abducted by this creature. But the shadows are so crushed, it almost feels like they’re in moonlight as opposed to sunlight — it’s so dark and foreboding. It really gives the feeling of that contrast.

That episode is a very good example. This is the bleach-bypass look that we implemented, which we pulled back a little bit from over the course of the first two seasons, culminating in Season 3, which was almost full color, probably the most extreme in terms of color, going the other way. Because The CW at the time wanted the show to be more colorful, we complied. But by the beginning of Season 4, I wrote to Eric Kripke, “We should go back toward what we had, because this is the look of the show, this is what we’re all about, darkness and shadows.” And he agreed. So we went back closer to the look that we had at first, but for specific scenes, the scary ones, while keeping a good relationship with The CW! [Laughs.]

When you have episodes that are more standalone in nature, do you go out of your way to make them look significantly different from those that are a continuing part of the story?

Yes, but also keeping in line with the generally dark look of the show, whether it’s set in a time-travel timeline, an alternate universe, the Bad Place or Purgatory.

When you mention time travel, I think of the episode “In the Beginning” — set in the early 1970s, when the boys meet their mother and father as young people just falling in love. We see their roots and we learn the truth about their mother, who was also a hunter.

I loved those episodes, because it was an occasion for me to go into a different mood, different colors and tones.

Regarding those episodes, do you immediately start a discussion with wardrobe, production design, and your other collaborators? Are they generally all sort of in that same interest, as well, to break the mold?

Questions and discussions were part of our daily routine. We were a very well-oiled machine. I never felt like it was another day at the office, even after 15 years. I never sensed that taken-for-granted attitude among the crew. Even in these last weeks it still feels like we’ve been on the show since the morning and wanting to do our best.

When composing a shot, do you generally consider Sam and Dean differently from the other characters?

We’re driven by the story and the director’s approach to it. Of course, we would favor our main characters in terms of camera angles and composition, achieving the hero shots that the show thrives on, but, first of all, for myself, I rely on what the director wants to see. I like to be the person who provides him or her with the means of achieving his or her vision, to be the director’s eyes and help him of her in any way I can to tell the story. I remember [executive producer and frequent director] Kim Manners always liked the low-angle shots, setting the camera lower than the eyes. Kim liked long lenses while others liked wide-angle compositions. It really depends on the director.

There’s so much of The X-Files in the DNA of Supernatural. I have to imagine that Kim Manners — who produced and directed so many episodes of that show — brought a lot of his experience to Supernatural, especially in those early seasons, to help it establish its ongoing look.

Kim was a shot designer; he spent a lot of time doing his homework, working out the mechanics of each shot, to the point where he was calling the shots with a technical precision that was impressive. Script revisions were a nightmare for him, especially when they were coming at a later stage in prep. And yes, he had a big influence on the early look of the show. And when you say there’s X-Files in the DNA of Supernatural, you are right — many people on set worked on X-Files the decade before. Kim was with us until Season 4, when he passed away halfway through the season. “Metamorphosis” was his farewell episode. It was a great loss for us. I learned a lot from him. He was a mentor for me and for many people on set.

What were some of the other contributions from directors from within the show — like executive producers Robert Singer and Philip Sgriccia — and from the outside?

Bob and Phil were major contributors to the concepts and rhythms of the show. Bob, in his capacity of co-showrunner, and Phil, in charge of post, both had enormous influence. Combined, they directed 94 episodes. They made and broke rules, challenging us, challenging me. They were from the inside, as was Jensen Ackles — who directed six episodes while acting in all 327. As the seasons passed, many directors worked on the show and brought their talent and vision, enhancing the experience of Supernatural and pushing the look forward. More than 60 directors worked on the show over the years. I have to name a few here: John Showalter [“Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid,” “Back and to the Future” and 24 more]; Charles Beeson [“Playthings,” “Changing Channels,” “The French Mistake,” “The Gamblers” and 10 more]; John Badham [“First Born,” “The Vessel” and seven more]; Richard Speight Jr., the actor who played the Trickster and the angel Gabriel [“Just My Imagination” and 10 more]; Steve Boyum [“The End,” “Swan Song” and seven more]; Eduardo Sanchez [“Rock Never Dies” and four more]; P. J. Pesce [“Good Intentions” and four more]; Amanda Tapping, the actress who played the angel Naomi [“The Future” and three more]; Nina Lopez-Corrado [“Tombstone” and five more]; Guy Norman Bee [“Asylum” and 10 more); Mike Rohl [“Appointment in Samarra” and nine more] and Stefan Pleszczynski [“Safe House” and three more]. All brought a special spark to the series and were wonderful to work with.

There are so many fantastic-looking series — on cable, network and streaming — so was there ever any feeling of needing the production values, the look of the show, to grow or expand to remain competitive in the marketplace? No show can afford to look like it’s being lazy on a creative level. Do you ever feel pressure about that, or is that not a consideration?

It is a consideration, but the pressure is more about doing the next shot as best as we can. Without being complacent, we like to think of ourselves as a good show, as something people keep coming back to, so we owe the show our best. But do I feel like I’m in competition with other shows? Not really even if we all are, in a way.

What things did you initially look for in each script? Did you keep an eye out for certain things where you could be more creative?

When I read a script for the first time, I read it for the story and for how it pushes the mythology forward. I’m interested in the character’s journey and by how they will be transformed. Words suggest images in the mind and, for me, they also carry their light, their mood. And that’s before I see any plans for a set or any location. Supernatural, because of the many layers in the overall story, because of the different time periods and universes we went through, offered an array of looks, an abundance of experimentation. First there are the looks in which Sam and Dean evolve before a case sets them on an adventure. That is their basic reality, whether they were on the road in a motel, up to Season 8, or, later on, in the Men of Letters bunker. This is their reality and it should feel like it’s the reality of our world, where the supernatural awaits. Then we can talk about the time-travel episodes which were another aspect of that experimentation on looks. For these episodes, or scenes, I should say, because time travel is often a portion of an episode, I liked to set them into a different look, so they have their own flavor. Two examples of this are “Frontierland,” episode 18 of Season 6, and “Time after Time,” episode 12 of Season 7.

In “Time After Time,” Dean goes back to 1944 and meets Elliot Ness. At that point, I was starting to move away from my film-based training and thinking and started to play more with the many possibilities offered by the digital medium, like the Kelvin setup in camera, for instance. For most of the back-in-time scenes in this episode, I set the Kelvin at 11,000, which gave me the brownish look from the natural daylight and artificial sources and the hyper-yellow-saturated hues from the practicals, which were regular incandescent bulbs.

What is your approach to lighting? What is your frame of mind when you light?

To answer this, it’s almost giving a definition of cinematography for myself. When I light a scene, I go with the emotion of the scene. Ultimately, the goal is to show an emotion before any word of dialogue is spoken, and I think this is the case for most DPs. What is the right mood, the right lighting for the scene? Those are the questions we’re asking ourselves all the time. Directors always have a take on how it should look, but sometimes they leave me to decide, because they know I’ve been on the show for so long and that I assure the continuity of the look. In the last few seasons though, we mainly had directors who have been on the show before, so they are familiar with its imagery. Having said that, every director will bring his or her own approach. For example, there’s one director who likes to compose with wide-angle lens, and I like it.

Is there a recent episode, that would be a good example of what you’re describing? One in which, the script had a scene that made you think, “This is where I could really play into the emotions of the situation, and try and help deliver that performance”?

There’s a scene in episode 14 of Season 14, “Good Intentions,” that I can use as an example: it’s a night scene between Mary [Samantha Smith] and Bobby [Jim Beaver] in the Alternate Universe as they converse, while Jack [Alexander Calvert] is entertaining kids in the background. It’s a touching moment and I think the ratio between light and dark creates a shell in which they have their moment.

What about the Men of Letters secret-headqurters bunker set, which has that great 1950s sort of industrial-Deco design? Can you tell us how it was to work there since it was introduced in Season 8 as the show’s first traditional standing set?

The bunker, which became Sam and Dean’s home, had its own set of challenges. Over the eight seasons that we have used the bunker, many different stories have taken place inside there. The bunker itself has been the starting point of stories because of its unique quality of being the repository of the knowledge and artifacts of the Men of Letters. It offered an unlimited source of plots and ideas. The challenge for me was to keep the scenes interesting even though they were set up in environments we had seen already. Again, and I hope I succeeded, I was going for the mood and emotions of the scenes, rearranging the lighting setups every time, not just switching the lights back on or off.

The physical set allowed me to do just that, because of the ease of lowering the grids and quickly repositioning the lights in the Library, and in the Crow’s Nest where they have the map table. The other parts of the bunker, like the corridors, the galley, the armory, the dungeon, and the heroes’ rooms, were well equipped with lights already positioned on the grids, thanks to my rigging gaffer, Michael Mayo, so, again, it was easy to position and focus them for the needs of the scenes. With the addition of flying certain walls all around the bunker it was a dream set to work in.

Since 2005, not only has there been a huge transition in terms of camera technology but in lighting as well, a revolution with LED sources. How did that affect your approach?

We started using digital lights from Kino Flo, the Celebs, in 2016 at the beginning of Season 12. To me, they were a leap forward in lighting technology and I saw the benefits of using them right away thanks again to Michael Mayo, who was instrumental in spotting them early on. We totally embraced them. We were the first show in Canada to use Celebs to light whole sets and we had the largest supply of them for more than a year. The main factor was their versatility — their dimming capability without changing color temp, their easy DMX remote-control aspect, and instant switching from 3,200 to 4,300 to 5600 and everything in-between. If I want to adjust the color temperature to match a house bulb in a table lamp, for instance, I can dial it in very easily, instead of adding gels to the existing conventional lights. So, yes, they’re great tools and we’re saving a lot of money in gels. [Laughs.]

And so much production time. Anything that can save five minutes on every set up adds up to hours, maybe saving your day.

Oh, totally! For instance, we’re daytime in a location and we know we’re going to go nighttime after that. So, during the day, let’s say, I have daylight coming through the non-corrected window, so we set these lights at 5,600K or an approximation of that — and then when night comes, it’s just a flip of the switch and I have a 3,200K- or 2,700K-balanced set. Like many DPs, I started in film, so I was raised and trained in the photochemical process with very defined parameters: 3,200K- versus 5,600K-balanced film stocks, conversion filters and so on. And then, when I started shooting digital, I realized that, on top of everything I knew from my film background, I could start playing with more elements the digital world was offering and introduced those as part of the palette, therefore moving away from my film background thinking. And it would, again, make our life easier on set and on a budgetary aspect. Another example: sometimes at night in the forest where no other lights are involved, I would set the Kelvin to 2,300 and use 3,200K balloons for practicality and budgetary reasons. By doing so, I shift the balance to the blue spectrum so the lighting becomes bluish, similar to adding a ¼ CTS to an HMI, or a ¾ CTB to a 3,200K light on a 3,200K-balanced camera. If I have an 18K in the distance on a crane, I would have a Full CTS on it and it would give me that bluish backlight, again because of the 2,300K setting. Once I let go of photochemical thinking, digital opened up a world of possibilities.

Did you at any point feel that you were resisting using some of the attributes of digital, before you started going down that road? Did you ever feel, like, “No, this is the way I know how to do it”?

There was a bit of a pinch when we abandoned film, but because I had worked in video, back in the 1980s and ’90s, the digital world was not new to me. For some years, back then, I was alternating between video and film. I could be doing a project on video and I would be switching to 35mm or 16mm after that. I had training in both formats, so I embraced digital, I really did.

How did the decision come to start shooting digital with the D-21? What kind of testing did you do to have the confidence to fully embrace that?

Even before we knew we were going to go digital we tested the D-21 because we were curious about it. I say “we” because it was a collective thinking. I have to credit my first AC at the time, Matt Tichenor, with the idea of bringing the D-21 on set and making some comparison tests between film and digital. Matt was a great element of the camera crew, always on top of everything technical. He left the show a few seasons back, but we have him as often as possible as an extra operator. That was Season 3, which as shortened due to the writer’s strike in 2007 to ’08, and we could feel digital coming. At the end of that season, it was finally decided that from then on, Supernatural would be shot digitally. And then, when it was a go, I did more extensive testing. My main worries were in relation with exterior shooting and especially bright skies, because, at that time, some 13 years ago, there were still notions that you couldn’t shoot skies properly with digital. But after these tests, I realized that yes, we could shoot outside against the sky, and that even the earlier versions of the digital cameras were quite tolerant and already advanced in terms of dynamic range. But still, a sky can get very bright at times and difficult to handle with whatever medium you use. In our early days of digital shooting, I created many LUTs for color and luminance control. In regard to bright skies, I created a LUT that I named SKY LUT. It was basically a white compression setup that allowed me to shoot against a bright sky without losing too much detail. It was very helpful. I also had LUTs for fluorescent Cool White, one to emulate the look of an 81EF filter on 3,200K film, and also black-and-white one. In Season 8, we moved to the Truelight on-set grading system using CDLs. With that system in place, there was no need to have a series of predetermined looks, as I was able to create the look of a scene, if not for a specific shot, on the go. So we saved the CDLs that were specific to a given environment and then recalling them as a starting point when we would find ourselves in the same or a similar environment.

“The work I’ve done here reflects, in parts, my approach to cinematography — and it will be the longest creative project of my career, I have no doubt — but I also look forward to new approaches. Supernatural was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

You sent me a list of some of the lighting instruments that your crew has created over time. We talked about the PMP setup, the Highways, but then, there are others that you mentioned, including the Angel light and the Azazel light.

Yes, for the Azazel light [named for a demonic antagonist on the show] I wanted a light that was flickering but not with a mechanical, strobe-y bias. I wanted something more organic, and that’s how the Azazel light came to life. I didn’t want to use a Magic Gadget sort-of device, so, with [rigging gaffer] Michael Mayo, we created a wavy-flickering light. I don’t think we have it anymore, because we used it a few times, and then it was dismantled and the parts went to something different. Regarding the Angel light: when an angel is killed, they go in a brilliant blast of illumination:

I needed a powerful source that would respond quickly to dim ups and downs. Standard 5K or 10K bulbs will always ramp, and are not as fast as I would like, especially when dimming down — the hot filaments linger and the light doesn’t disappear fast enough. So, Michael built a device that was made of 12 x 1,000-watt quartz bulbs, so, 12,000K, with each bulb on a different channel. It’s fast, and gets very hot very quickly. It’s a reasonably sized box — 60cm x 10cm — and weighs a bit, but we can suspend it or whatever. This is something we created, along with other instruments.

As you complete your final weeks of production, how do you feel about 15 years of work on Supernatural as a major part of your life and creative legacy? I’m sure there is a lot of introspection going on with your crew.

Among my crew — in particular, gaffer Chris Cochrane, rigging gaffer Michael Mayo and rigging grip Dave Neveaux — there is talk about what will come next, because we have formed a family and we would like to continue the dynamic we have created after so many years. On the camera crew, operator Brad Creasser is my “accomplice.” I know he wants to move on to shoot, and he has done such a great job shooting scenes when I was away, perfectly matching or anticipating what I would have done. I’m encouraging him to do so even though I would miss him greatly as a camera operator. Although I’m sad [the show] is coming to an end, I’m happy it’s ending the way it is. We’ve lived something unique and special, but we will move on. The work I’ve done here reflects, in parts, my approach to cinematography — and it will be the longest creative project of my career, I have no doubt — but I also look forward to new approaches. Supernatural was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Special thanks to Serge Ladouceur for his diligent participation in the creation of this story, and to Warner Bros. Television and The CW for generously opening up their photo archives.