Suspiria: Terror in Technicolor

Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC recalls the details of his approach to Dario Argento’s legendary 1977 horror film.

Author’s Note: This retrospective article was originally published in the February 2010 issue of AC. A PDF of that original magazine layout can be found here.

The horror film is stylistically rooted in German Expressionism of the 1920s, but the 1970s found the genre in transition. Smash Hollywood hits such as The Exorcist (1973), Jaws (1975), Carrie (1976) and The Omen (1976) not only offered graphic shocks, but also transformed or completely shed the genre’s traditional trappings of ghouls, ghosts and goblins. Instead, the characters and situations became somewhat familiar, the settings were contemporary and even homey, and the films’ largely naturalistic cinematography firmly grounded the fantastic in reality.

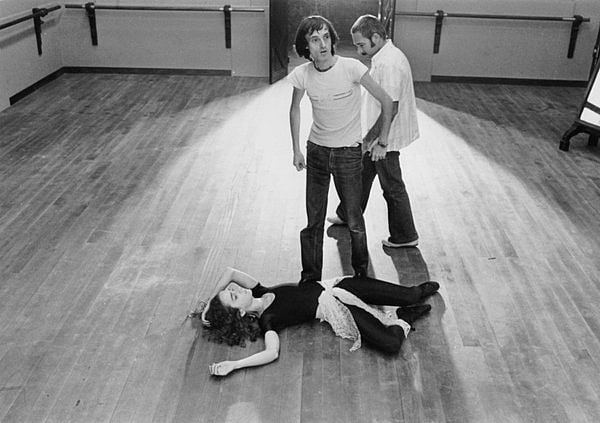

A world away, in Italy, filmmaker Dario Argento had carved out a unique niche in the fright-film business with such thrillers as The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970) and Deep Red (1975). These atmospheric stories, populated with demented killers and boasting grotesque set pieces, drip with equal parts gore and suspense — pop-culture products of the changing times. Flush with success, yet seeking a new creative direction, Argento then decided to envelop himself in the macabre lore of Old Europe. Working with fellow screenwriter Daria Nicolodi, he concocted a heady tale of witchcraft and the occult set in a ballet academy poised on the edge of Germany’s Black Forest. There, a young American student, Suzy (Jessica Harper), becomes the target of Mater Suspirium, the Mother of Sighs, a demonic headmistress whose murderous minions dispatch those around Suzy with operatic aplomb. Their elaborate, Grand Guignol-style deaths unfold in a series of blood-chilling sequences.

The evocatively titled Suspiria (1977), photographed by Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC, is a feast of intensely expressive images and sound. A creative touchstone among horror aficionados, the picture stands as an example to all filmmakers seeking to create tangible onscreen synergy between story, design, direction and cinematography.

Inspired in part by the Technicolor grandeur of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Argento wanted to achieve a palette rich with primary hues and deep blacks. Tovoli notes that when Argento approached him about the project, “I had not seen any of his films, but, of course, I knew him as a very successful director.” At the time, Tovoli was perhaps best known for his work in Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975). “Horror films did not interest me at that moment of my professional life — I was a very impressionable guy, you see,” he continues. “But I do remember one summer afternoon in my apartment, when I heard a loud noise coming from the street. I looked out and saw a huge crowd sprinting from one movie theater to another. I later discovered that both theaters were showing Argento’s The Cat O’ Nine Tails [1971], and they were hoping to find a free seat! I said to myself, ‘A director who provokes such brisk movement in a crowd should be a very good one!’ After that I searched to see all of his movies. Ignorance is a curable sickness!”

Tovoli was intrigued by Argento’s ideas for Suspiria. “I think describing it as a Gothic fairytale is correct, but normally, the director and cinematographer do not sit down the first day we meet and say, ‘This time we will do a Gothic fairytale.’ Instead, we start speaking about many subjects relating to — or sometimes not relating to — the film we have to do. A good director, or in this case a great one, does not give precise recipes or strict commands, but instead searches to influence his collaborators with the originality of his dream.”

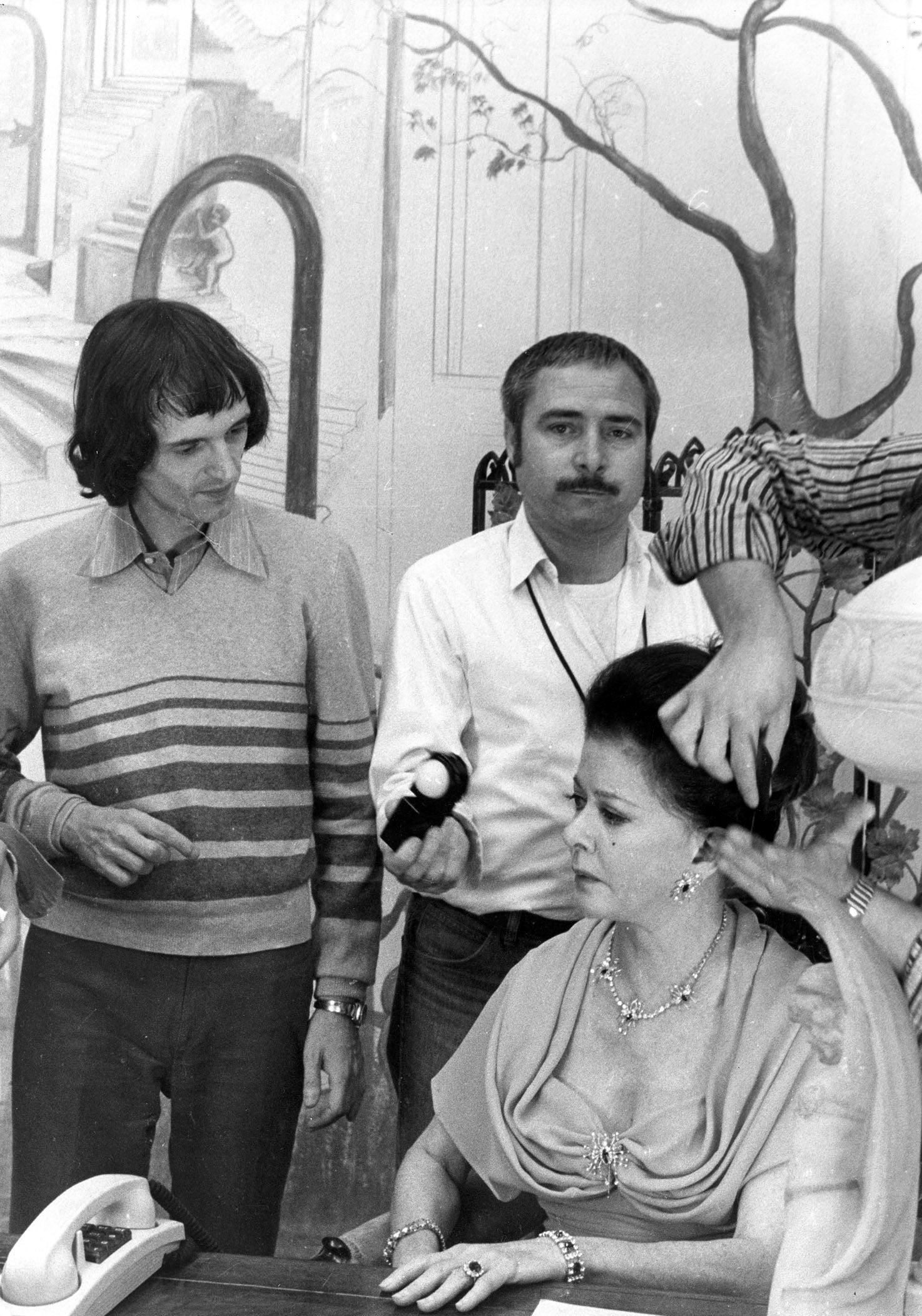

For Tovoli, one fundamental issue on Suspiria was “the choice of colors and the way I utilized them in accordance with [production designer] Giuseppe Bassan, who was working under Argento’s inspired guidance. We were often making our decisions in the flow of the shooting, without too many elaborate consultations or directions, but just in a kind of magic comprehension.

“I decided to intensively utilize primary colors — blue, green and red — to identify the normal flow of life, and then apply a complementary color, mainly yellow, to contaminate them,” continues Tovoli. “A horror film brings to the surface some of the ancestral fears that we hide deep inside us, and Suspiria would not have had the same cathartic function if I had utilized the fullness and consolatory sweetness of the full color spectrum. To immediately make Suspiria a total abstraction from what we call ‘everyday reality,’ I used the usually reassuring primary colors only in their purest essence, making them immediately, surprisingly violent and provocative. This brings the audience into the world of Suspiria.” But the brightly hued artifice also has a certain distancing effect on the viewer. “You say to yourself, ‘This will never happen to me because I have never seen such intense colors in my life,’” says Tovoli. “This makes you feel reassured and, at the same time, strangely attracted to proceed deeper and deeper into this colorful journey.”

The film’s opening shots quickly transport the audience, as Suzy makes her way through the Munich airport on her way to the ballet academy. “With colors forbidden in reality, the Munich airport becomes Suspiria airport,” says Tovoli. “Then, the first close-ups of her in a cab, as it’s raining furiously outside, express perfectly the dynamics of the full color palette I sought for the rest of the film — the pulsating, mixing and alternating primary and complementary colors.” Like Disney’s Snow White, to whom Harper bears more than a passing resemblance, Suzy is soon lost in a strange world of magic and witchcraft.

“I was deeply inspired by Jessica’s interesting face, by its volumes and proportions, and her beautifully expressive eyes,” Tovoli says of his star. “After I prepared the light and she arrived on the set, she was immediately shining so brilliantly that I was astonished every time, as was Argento. Of course, I tried to light her laterally as much as possible, with almost no light in the axis of the camera, to add a sense of perspective to her face. On other films, I had registered the fact that the lens loves some faces, but in Jessica’s case, the relationship was really phenomenal.”

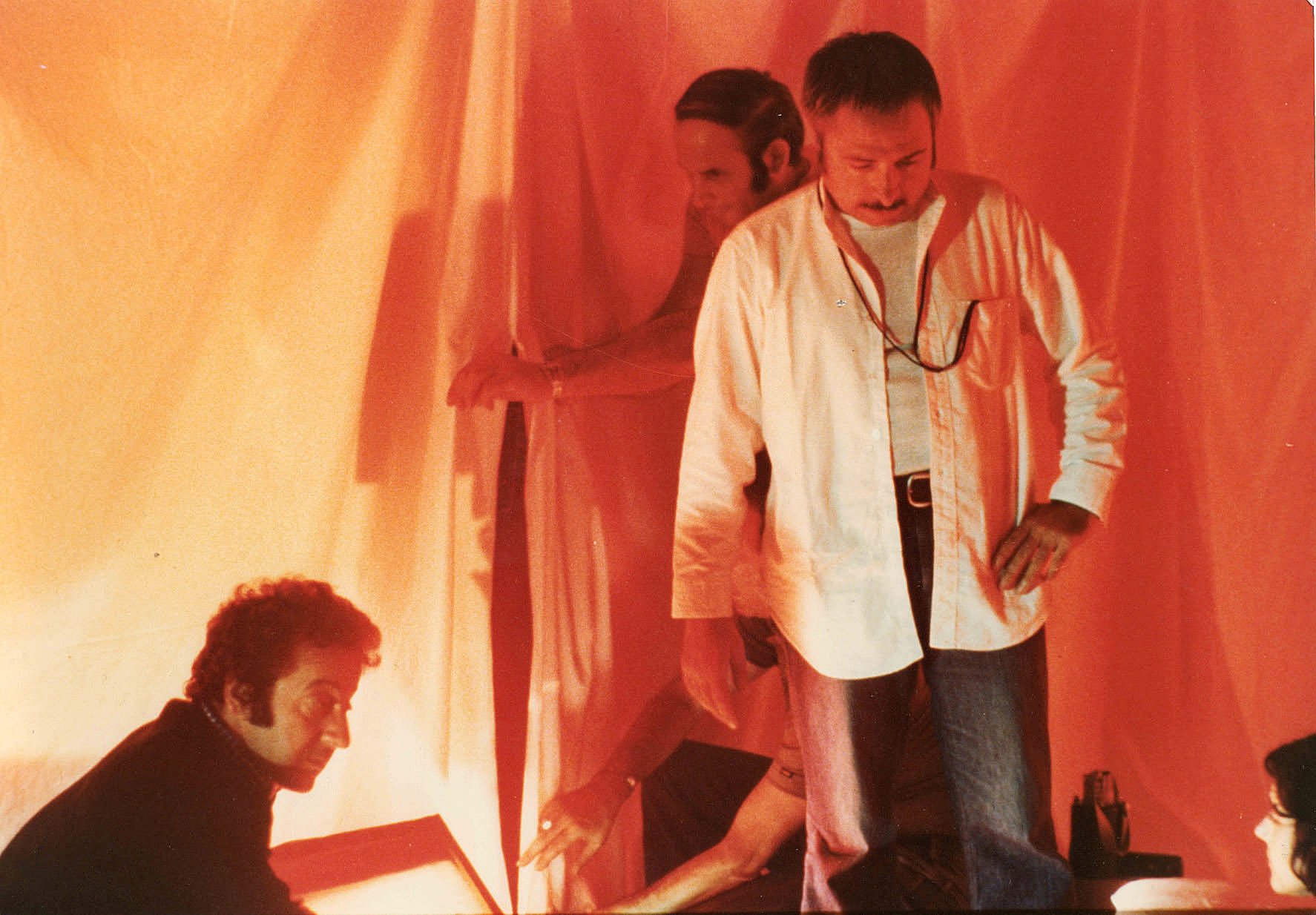

The theatrical, expressionistic approach Argento and Tovoli sought for Suspiria was unusual for the time, especially for a contemporary film. “It was surprising for a great part of our crew, who had never met a cinematographer who wanted to put the strongest possible lights so close to the actors through colored-velvet screens,” says Tovoli. “But it was very new for me as well. I had never lit a film like this before. For many years at the beginning of my career, I prayed only for the most natural light possible.”

Tovoli recalls a pledge that he and fellow future ASC member Nestor Alméndros made while they were attending the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome. “We promised over two glasses of good Tuscan red wine to never abandon the marvelous religion of real light,” he says. “I respected that oath for maybe a decade, but then I started to be quite bored. Alméndros, who was much more serious about this kind of thing than I, continued in the same direction with the most enviable success. Meanwhile, I started to study the work of the black-and-white cinematographers working at Cinecittà in Rome, in Hollywood and elsewhere. I searched to reconstruct their unbelievable lighting and complex technique; I watched the films over and over to learn how they achieved such great artistic results.” Among his favorites were Italian cinematographers Anchise Brizzi, Arturo Gallea, Ubaldo Arata, Carlo Montuori, Massimo Terzano, Otello Martelli, Aldo Tonti and, later, Aldo Graziati and Gianni Di Venanzo. “Working in black-and-white with Antonioni, Di Venanzo brought a substantial change to the technique, utilizing many small diffused lights for interiors instead of bigger Fresnel units,” Tovoli notes.

The cinematographer was initially reluctant to sign onto Suspiria “because I was conscious of my lack of experience and, more importantly, my lack of real passion for that kind of film,” he explains. “I’ve never accepted a job just to take a job. Also, even in the most insignificant film, I always searched to find some significance. That, of course, was not at all the case with Suspiria. But fortunately, Argento insisted I join him, and I still do not know why.

“I chose my camera crew very carefully,” he continues. “I brought in Idelmo Simonelli, one of the best camera operators, a true star. When he said, ‘This is by far the best take,’ it was by far the best take! I also brought the best first camera assistant, Peppino Tinelli; the best grip, Mario Moreschini; and the best gaffer, Alberto Altibrandi, whose nickname was ‘Gnaccheretta’ [Castanet].”

With only a few weeks of prep, Tovoli began camera and lighting tests in earnest. “After my first conversation with Argento, I vaguely imagined how to technically achieve this radical departure from my previous lighting style, but also, I needed to know if I had truly abandoned naturalism,” he says. “On The Passenger, I searched to force the strength of the real light, often overexposing, bringing the negative near the shoulder of the sensitometric curve to burn up some of the detail. In a way, this is what I did on Suspiria as well, but at a much higher level, ‘overexposing’ through the intensity of a specific color in a specific shot, with the negative [Eastman 5254] carefully exposed at the center of the curve. I utilized this technique on every shot in the film. I was always telling the production designer and scenic painter, ‘More red! More blue!’ I made the same recommendation to my very patient gaffer, Alberto, and, like a good friend, he asked me, ‘Are you sure? There is already a lot of green. It’s becoming quite disturbing!’ And to my inalterably happy face he asked, ‘Are you searching to be fired?’”

Part of Tovoli’s approach was to make extensive use of frames of brightly colored velour and tissue paper set in front of Arcs positioned very close to the performers. “I wanted to create light that would simulate the color coming from pots of paint thrown very respectfully on the actors’ faces, recalling Jackson Pollock’s fundamental gesture of splashing pure color on the canvas. In my imagination, our canvas was our actors’ faces. Soon, someone calmly explained to me that this was not possible for multiple reasons, and I was forced to find an alternative method of lighting the actors’ faces and, to an extent, the backgrounds, with the strongest possible light as close to the subject as possible. While shooting, our actors were very often reasonably worried they might be burned!”

Tovoli also employed mirrors to change the quality of the light. “The stratagem of the mirrors could double the distance between our light sources and the scene,” he explains, noting that he was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s use of mirrors in his work. “If I have to choose one impressive reference, why not go directly to the best? It’s always better to tap in at the highest level! I utilized mirrors not to destroy enemy ships, as Archimedes did in the war between Siracusa and Rome, but to destroy with a violent shaft of hypercolored light a universally ‘elegant’ or ‘refined’ image. This was driven by my desire to always go beyond what would be conventionally accepted. The aesthetic concept on Suspiria — and Argento will forgive me if I pretend to speak for him — was never to subtract, but to add.”

Bassan’s extensive use of wildly textured backgrounds, geometric shapes and colored surfaces add greatly to the picture’s crazy-quilt visual quality, and Tovoli sought to keep such elements in crisp focus. “Sharpness has always been another of my profound beliefs, in part as a form of respect for the optics specialists who work hard every day to improve the rendering of the lenses,” he says. “I do not use, or very scarcely use in lighter values, diffusers or colored filters. And I absolutely never used them on Suspiria. In general, I am not interested in ‘pictorial’ images. Watching a film, I get bored and lose interest when I see diffused smoke where there is not any justification for it apart from the desire to create a nice atmosphere. I’m tempted to call the fire brigade!

“When I first started to do photography, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston and Henri Cartier-Bresson, among many others, opened my eyes to the vast territory of sharpness and contrast as primordial values in photography — and cinematography, of course. On Suspiria, I lived with the illusion that I could make sharp the simple, flat volume of a monochromatic wall by using the pure intensity and pulsating vibrations of the color itself.”

Using Mitchell BNC and Arri 2-C cameras, Tovoli shot Suspiria in 2.35:1 Technovision anamorphic, a format he loves deeply. “The glorious Technovision anamorphic lens!” he exclaims. “The incredibly passionate Enrico Chroscicki believed so strongly in great panoramic images that he went to Paris in the early 1950s to search for the survivors of Henri Chrétien, the French astronomer who designed the Hypergonar lens, from which the first anamorphic lens was later derived. Chroscicki told me he also met with a very old collaborator of Chrétien’s in Nice, and found in a dusty drawer not only the original drawings of two lenses but also a single optical anamorphic element to be put in front of a normal primary lens. Thanks to this almost archaeological discovery — I baptized him the Winkelmann of lenses — Chroscicki, in his little workshop in Rome, made just one lens! It was a 50mm, and he rented this single lens for years before he had the money to build a full series of anamorphic lenses. How could I not shoot Suspiria with Enrico’s anamorphic Technovision lenses? Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] has shot all his films with Technovision lenses!”

Eastman 5254, a 100-ASA negative, “had beautiful contrast values and colors, which I admired, and that was so important for the Technicolor process separations we were to make from our negative, because we planned to force, violate and deteriorate the image’s normal color range,” he adds. From the outset, the filmmakers intended to use Technicolor’s legendary dye-transfer — or imbibition — printing process as the final step in creating the haunted realm of Suspiria. Technicolor Rome shut down its IB printing in 1978, making Argento’s film one of its last dye-transfer projects.

Tovoli recalls, “Technicolor Rome applied the negative-developing and positive-printing system with extreme accuracy, and they agreed, maybe for the first time in their history, to make a minor but important modification for us. They agreed to lose a diffuser that was typically used to slightly flash the yellow-cyan-magenta imbibed matrix, thus preventing any possible bleeding of the colors outside the physical contours of each image. The possible bleeding of colors was exactly what I was searching for with Argento — we wanted more contrast, more vibrating colors — so I proposed to Carlo Labella, the nicest man and a very talented color timer, that we lose this little attenuation of the color contrast. I am not ready to forget his friendly smile as he listened to my apparently absurd proposal!” Also, for the matrix printing of the cyan layer, lab technicians used a special filter that was more selective for the color red, which was particularly complicated to render in the dye-transfer process but also a key component of Suspiria’s palette. The filter enabled the post team to faithfully reproduce all the information present on the original negative.

Tovoli recently revisited Suspiria at Technicolor Rome to supervise a new HD transfer, which will result in a Blu-ray release this spring. “I worked with a very talented colorist, Fabrizio Conti, and we tried to stay as close as possible to the look of the original,” he says. “I think we did an extremely good job, but it is impossible to compare even the best digital master to a film printed with Technicolor’s dye-transfer process, especially for a film as extreme as Suspiria!”

The cinematographer’s bold use of color is showcased in one of Suspiria’s most bravura sequences, in which Suzy’s friend Sara (Stefania Casini) is relentlessly pursued by an unseen assailant. Terrified, she runs through a labyrinth of colorfully hued corridors in the boarding school, finally slamming shut a heavy door behind her. Leaning against it, she sees a straight razor slowly slide between the door and the jam as her attacker tries to flip open the simple lock. In a panic, Sara spots a tiny window that offers possible escape. Climbing through it, she cannot clearly see the room she is entering. She jumps to the floor, only to find the chamber filled with coils of barbed wire. Trapped and helpless, she struggles in this blue-tinged nightmare until the killer reaches her.

“That is one of my favorite scenes because Argento left me free to create a color symphony following only my emotion and taste,” says Tovoli. “That is very rare in the relationship between the director and the cinematographer. Looking at that sequence today, I realize I made it in a state of total pleasure, going on shot after shot with my collaborators, almost blindly utilizing the new alphabet of colors that had become our instinctive color language. The red, of course, is the aggression and danger, the blood that the unknown pursuer will soon force out of your body with his knife. The blue is the terrifying death sentence already pronounced and a color that accompanies you into the sinister world of death. The delicate orange coloration of the little window high in the wall of the room is the momentary illusion of safety, a painting done with colored lights. Then there is the shining metallic blue of the barbed wire, like a carnivorous plant that will capture and almost digest you forever. Such a very rich bouquet of gifts for a cinematographer! Thanks, Maestro Argento! The sequence of colors in the frantic pursuit was not planned at all. I made it absolutely on the inspiration of the moment.”

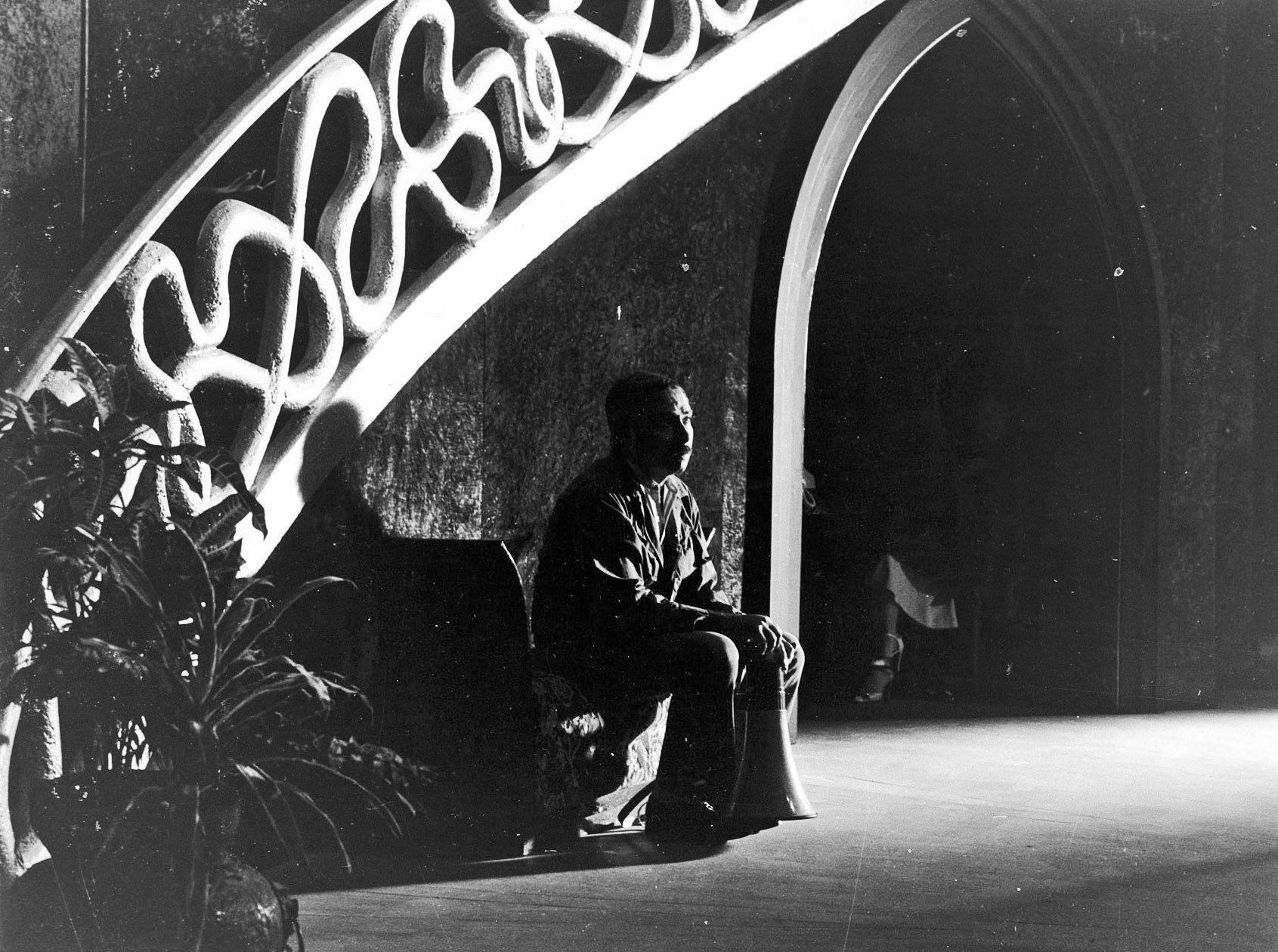

Conversely, another key set piece finds Argento and Tovoli bleeding off their elaborate color scheme to render an almost monochromatic milieu of nocturnal mayhem. In the sequence, blind pianist Daniel (Flavio Bucci) and his guide dog enter the vast Konigsplatz Square at night, the pale gray stone of the surrounding buildings starkly set against the darkness. Atop one roof, an imposing statue of a huge bird of prey peers down on the frightened man. Daniel cannot see that the creature disappears, but hears the flapping of great wings as something swoops down over the square at him as his dog barks incessantly. Then, in one of the great twists in horror cinema, Daniel is murdered, with his shockingly red blood punctuating the moment.

For Tovoli, the Konigsplatz Square offered a tremendous lighting challenge. “What kept me up at night was the dimension of the location,” the cinematographer says. “Since then, I have lit bigger spaces, including the huge Pula Arena in Croatia for Julie Taymor’s Titus [1999; AC Feb. ’00]. Knowing that Hitler utilized the Konigsplatz Square for his parades and speeches did not reassure me at all! We decided to not use color in the scene to enhance the loneliness of the empty space and make the sudden explosion of bloody red [more dramatic].

“The bird’s [point-of-view shot] was a very clear idea of Argento’s that we realized quite easily by running a thin steel cable from the top of one temple to the ground by a hand-released hook. When the ground hook was released, the elastic part of the cable brought our Arriflex camera off the solid ground and into the air to soar over the square. Of course, we got quite excited about the shot and pushed the special mechanical effect responsible to delay the release of the hook at the very last possible second.” The resulting POV effect adds an ingenious sense of menace to the already flamboyant scene.

“Discussing the film this way brings back the feeling of total happiness, a fabulous shooting time in which a young cinematographer not at all intimidated by the task before him took the opportunity to collaborate with a great director and sweet man named Dario Argento,” muses Tovoli, who would later shoot such Hollywood suspense films as Reversal of Fortune (1990) and Single White Female (1992). “I believe it is this human secret, not a technical one, that is behind the lasting long life of Suspiria.”

Afterward;

The author thanks D’Arienzo Antonio, Robert Hoffman, Bruce Heller and Rob Hummel for their assistance with this article.

In October of 2017, Tovoli was honored at the first annual IMAGO International Awards for Cinematography with their Lifetime Achievement in Cinematography Award for his extensive body of work.

Tovoli recently collaborated with Synapse Films on a 4K remastering and deluxe release of Suspiria on Blu-ray in the U.S., and this article was re-published in the included liner notes booklet.

You can read more about that restoration work here: Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC Joins Restoration of Fright Classic Suspiria.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, check out more AC Historical Coverage.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.

A complete story on the 2018 Suspiria remake, shot by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, can be found here: Suspiria: Season of the Witch.