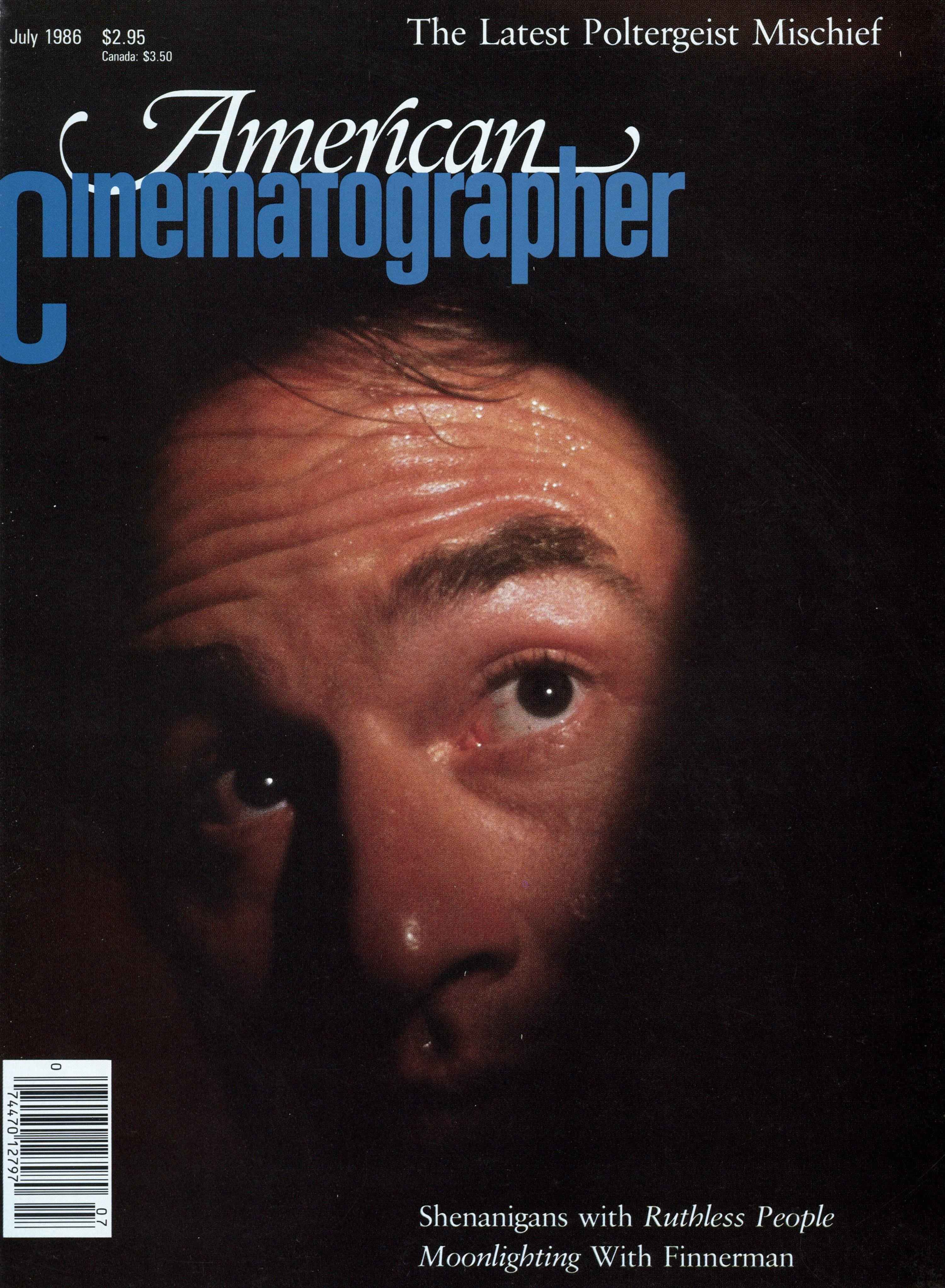

Tender Loving Care for Moonlighting

Director of photography Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC discusses the creative approach that makes this unorthodox comedy work.

It was just a quick take of Cybill Shepherd exchanging some snappy dialogue with Bruce Willis; just a few seconds out of 60 minutes.

But director of photography Gerald Perry Finnerman, ASC sees something no one else does — a tiny spot of light on Shepherd’s nose. If you blink, you miss it. Maybe it will be imperceptible on the video screen. Perhaps no one else will care. However, Finnerman does. He calls the problem to the director’s attention, adjusts the light, and shoots the scene again.

That’s Moonlighting, 80 to 90 pages of script (50 is more typical for an hour-long TV episode) which requires nine long days to shoot, plus large doses of tender loving care.

There is nothing else quite like it. There’s great dialogue, and if you think that’s something that doesn’t concern a director of photography, try shooting some of those fast-paced scenes with dual mikes and overlapping lines.

There’s Shepherd and Willis, a “1980s version” of Bogart and Hepburn. Try lighting Shepherd, who never stands still or looks in the same direction twice; then factor in Willis for a two-shot. It takes more than a little thinking, and a great deal of attention to detail.

Try shooting all of the script pages, with maybe 35% of production done at practical locations, day and night, interiors and exteriors, where no two settings are ever the same. Try a theater that seems as big as the Los Angeles Coliseum, and as difficult to light; or a posh restaurant; or a dark parking garage; or a seedy bar.

In an industry where imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, there are no Moonlighting clones. This isn’t going to be an easy act to follow.

Finnerman recalls that it started with a call from Jay Daniel. “I had worked with Jay when I was at Columbia between 1975 and 1980. He was a producer for Police Story and a number of other programs. Jay said they [ABC Circle Films] had an idea for a dramatic comedy — something like The Thin Man.”

The story: Shepherd plays the part of a successful model whose business agent takes off with most of her money. Willis fast-talks her into keeping a bogus detective agency that was part of the scam. The producers wanted a very high-class look. They wanted Shepherd to look not just good, but fantastic. And Willis, for the concept to work, must provide balance for Shepherd’s brilliant glamour with his unpolished demeanor.

Daniel and producer-writer Glenn Gordon Caron laid out the parameters for shooting Moonlighting in their first meeting with Finnerman. Most of all, they told him to be daring. That’s like telling a thoroughbred race horse to feel free to run.

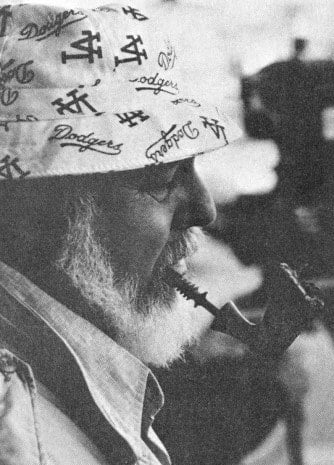

Finnerman grew up in Los Angeles. His father, Perry Finnerman, Sr., was an operator for Bob Surtees, ASC and Harry Stradling, Sr., ASC, and later became a contract cameraman at Warner Bros. Finnerman earned his degree at Loyola University, and did graduate work in secondary education with a minor in abnormal psychology at UCLA. During vacations he worked in the loading room at Warner Bros.

“All I ever wanted to do was become a cameraman.”

Finnerman started as an assistant on his father’s crew. When his father died during the mid-1950s, Harry Stradling, Sr. took Finnerman under his wing. He worked as an assistant and later as an operator for Stradling, Sr., who recommended him for his first job as a director of photography when the Star Trek TV series started in 1966.

Finnerman earned his first Emmy nomination for visual effects photography on that show and his second, in 1973, for Kojak which was produced by Universal Studios. There were three more nominations during his Columbia and Universal years, including The Gangster Chronicles (Universal, 1980-’81), From Here to Eternity (Columbia, 1979-’80) and Ziegfeld (Columbia, 1977-’78); the latter yielded an Emmy for best achievement for long form show in cinematography.

One of the most important rules for shooting Moonlighting is that zoom lenses are never used. The show is shot entirely with primes. The camera is almost always moving, tying the people together. That dictates the use of lots of dolly track and cross-lighting.

“You can’t dolly around a room with a 10K in the back of a camera,” Finnerman says. “We’ll go from a master to a two-shot, and then look over someone’s shoulder, and we are into a closeup for a reaction shot. And, it all has to blend with the master.”

For two-shots, he borrowed an idea from the past — split diffusion. Maybe he’ll have a Mitchell C filter in the half of the matte box, and clear glass in the other half; or a Mitchell A or B, or various other combinations. This allows him to soften Shepherd’s half of a two shot in very subtle contrast to Willis depending upon the scene and setting.

For his tools, Finnerman selected Arri BL-3 cameras with Zeiss prime lenses, Eastman color high-speed negative film 5294 for interiors and night exteriors, and Eastman color negative film 5247 for daylight.

“I’ve used Zeiss lenses for years,” Finnerman says. “There’s nothing sharper, or crisper, and if you want vivid images, what’s more important than that?”

All camera gear is rented from Ultravision. “They do an excellent job of servicing and maintaining their equipment,” says Finnerman. “That’s the key. Any camera is going to have problems if you don’t maintain it. We’re shooting 12 to 14 hours a day. Once we shot for 20 straight days. And we haven’t had a single down time problem from our Arri BL-3s.”

Finnerman also tested all of the available low-light sensitive films before settling on the Eastman 5294. “It has the latitude that I need for this show,” he says. “It holds up well at low-light levels; the blacks stay black, the tones are rich, the faces don’t go muddy, and the shadows don’t go green.”

The photography is highly stylized. Finnerman lays out every master shot like a complex ballet. He has dolly track and 3/4" thick plywood boards painted to match every carpet color on standing sets at 20th Century-Fox. One stage has sets for Shepherd’s home. Another stage houses the office complex for the Blue Moon Detective Agency.

Finnerman uses diverse lighting packages — “They [the producers] haven’t denied me anything,” he says — mainly inkies for interiors and HMIs for daylight. Many locations are shot with practical light and small boosters for modeling and balance. He generally avoids overhead light — “That flattens the image,” he explains.

But, in one of the office sets, where the ceiling is only 8' high, Finnerman uses ambient light overhead. Otherwise, most of his light comes from units on the floor.

His stages are generally lit so he can work at stop T/4 or 4.5 which he feels yields the best resolution with the Zeiss primes. But, of course, this also depends upon the location and the particular illusion.

“You have to be flexible,” Finnerman says. “We have very little time for preparation. Usually, I send an electrician with a Kelvin meter to locations ahead of us so we’ll know how to approach lighting. That tells us what we need — do we have to mix with fluorescents? Do we need inkies, or HMIs or color correction filters?”

There was one location at a hotel near Los Angeles International Airport. The lobby was surrounded by windows, and it was a very overcast day. Finnerman tinted the windows with neutral density material, used a coral filter to warm up the image a bit, and worked at stop T/1.8. “It was a warm, lovely look, which was what that scene required,” he says.

Finnerman uses four basic exposures with the 5294 film. Most scenes are photographed in tungsten 3200K light at the 400 exposure index recommended by Kodak. For night interiors, he’ll go down a half-a-stop and rate the film for an EI of 650. For low-key, moody scenes, he goes down a full-stop to EI 800. “We still get very rich blacks (at El 650),” he says.

Finally, in moonlight, Finnerman rates the film at EI 1200, and still the blacks don’t go milky. “It’s a very subtle film,” he says. “And DeLuxe Labs does wonderful work with it.”

“In a way, it reminds me of Star Trek. Viewers are fiercely loyal. Working on this show is like belonging to a special club.”

One of the keys is the way Finnerman lights Shepherd. “Every frame of Cybill is lit like an individual portrait,” he says. This is done with the aid of a 10-dimmer console which allows Finnerman to subtly vary the angles of light on Shepherd as she paces through the office complex or her home.

The stage sequences are lit almost like a three-camera film show,” he explains. “There are two people on the dimmer console. Anyplace she stops, we put the right key on her and bring down the level in the area she just left.” It’s very smooth.

“Her best lighting is up high... butterfly lighting, from the Harry Stradling, Sr., school of photography... or Bob Surtees... or Burnie Guffey. All three of them mastered the art of putting a beautiful actress in her best light by masking tiny wrinkles and laugh lines.”

Also, there is always an obie on the camera to put some sparkle in the performer’s eyes. That you expect. But, Finnerman adds some nice twists when it comes to lighting Shepherd.

“Most blonde hair goes white when you backlight,” he explains.

Not Shepherd’s. She comes through as a rich honey blonde, and that’s no accident. Finnerman uses straw #54 color gels on the lights for daylight scenes, and adds a half MT filter to warm her hair up a bit for night scenes. Add backlighting to that mix, and the results are spectacular. It’s almost like a commercial; only Finnerman does it while he is shooting nine pages of some very complex photography a day.

“One trick I learned from Harry [Stradling, Sr.] is that in situations like this you fill-light the woman and crosslight the man,” he says.

Finnerman has special brackets on the matte box that allow him to use ring diffusion and sliding diffusion — which most directors of photography haven’t used for 20 or 30 years. “It’s the kind of thing that people like Stradling, Sr., Surtees, Guffey and my own father used to do so well with actresses like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford,” says Finnerman. “Sliding diffusion disappeared with the zoom lens. Our use of prime lenses lets us use enhancements like this.”

Finnerman even employs a special netting that Stradling, Sr., used to diffuse the light on Audrey Hepburn when he shot My Fair Lady. “I was Stradlng, Sr’s., operator when we won the Oscar for My Fair Lady, and I’ve saved that netting for all of these years,” he says.

The production schedule can be best described as hectic and vigorous. Finnerman figures that each page accounts for some 30 seconds of air-time, twice normal because of the fast pacing and rapid dialogue. “There is a lot of double miking and overlapping dialogue,” he adds. “I believe the words and pictures complement each other.”

Because of the nature of the show, the producers always want to be able to see faces and expressions, and reactions to dialogue.

Much use is made of multiple cameras to cover action from various perspectives. This makes lighting even more complex. There are many car shots, and Finnerman typically shoots these with three Arri cameras. Two of the cameras are on one shots for individual reactions. A third is a cross camera set for a deep focus on a two-shot.

The front cameras are set on the hood at stop T/4 and they are loaded with the medium speed 5247 film. “We’re shooting in daylight with a No. 85 filter on the camera lenses,” he says.

The side camera has a 35 mm lens, and it is set for a tremendous split at stop T/6.3 or 8. “I use the high speed film for this because it gives me two stops,” Finnerman explains.

Even in a tight shot like this, there is no problem mixing 5247 and 5294 films. “They’re that close in image characteristics,” says Finnerman.

[Editor's Note: Orson Welles made his last appearance onscreen when he recorded this intro for the "The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice" episode. He died five days prior to its airing.]

That brings us to “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice,” a mainly black-and-white episode, which received broad national media attention. “It was Glenn’s idea,” says Finnerman. “He asked me how I would like to shoot a black-and-white episode. I had never shot anything in black-and-white, though I was Harry’s operator on some black-and-white features.”

The story involves a visit that the detectives make to see a prospective client at an old night club, The Flamingo. They hear about a murder that occurred at the club 40 years earlier. A musician was murdered and his wife, a singer with the band, was arrested. However, there were still doubts as to whether her lover, a trumpet player, actually committed the crime or was a reluctant accomplice.

That night both Willis and Shepherd dream about the murder — in black-and-white. In Shepherd’s dream, the wife is an innocent bystander who gets blamed for the murder. In Willis’ dream, the trumpet player marches to the scheming wife’s tune.

Finnerman’s first thought was that he could shoot the whole thing in color, and have the lab or video post-production house pull black-and-white prints. However, once he heard the full scope of the idea, he was fascinated and focused on shooting the dreams in black-and-white. “The idea was to shoot one dream with a 1940s MGM look and the other in the Warner Bros, style, more down-and-dirty,” he says. “We had a meeting involving the art director, production designer, wardrobe, the producers and myself, where we started thinking in terms of gray tones. Colors record differently on black-and-white panchromatic film depending upon their reflectivity. Blue photographs as white, red comes through dark, and so on.”

“We settled on A Streetcar Named Desire as a model for Cybill’s dream, and Casablanca for Bruce. Then, I forgot all of the rules about shooting color.”

Props selected for the black-and-white episode were mainly black, brown, beige and red. Finnerman knew a retired makeup man, Dave Grayson, who had broad black-and-white experience, and wardrobe developed costumes which were properly color-corrected. Dave supervised the makeup on the show.

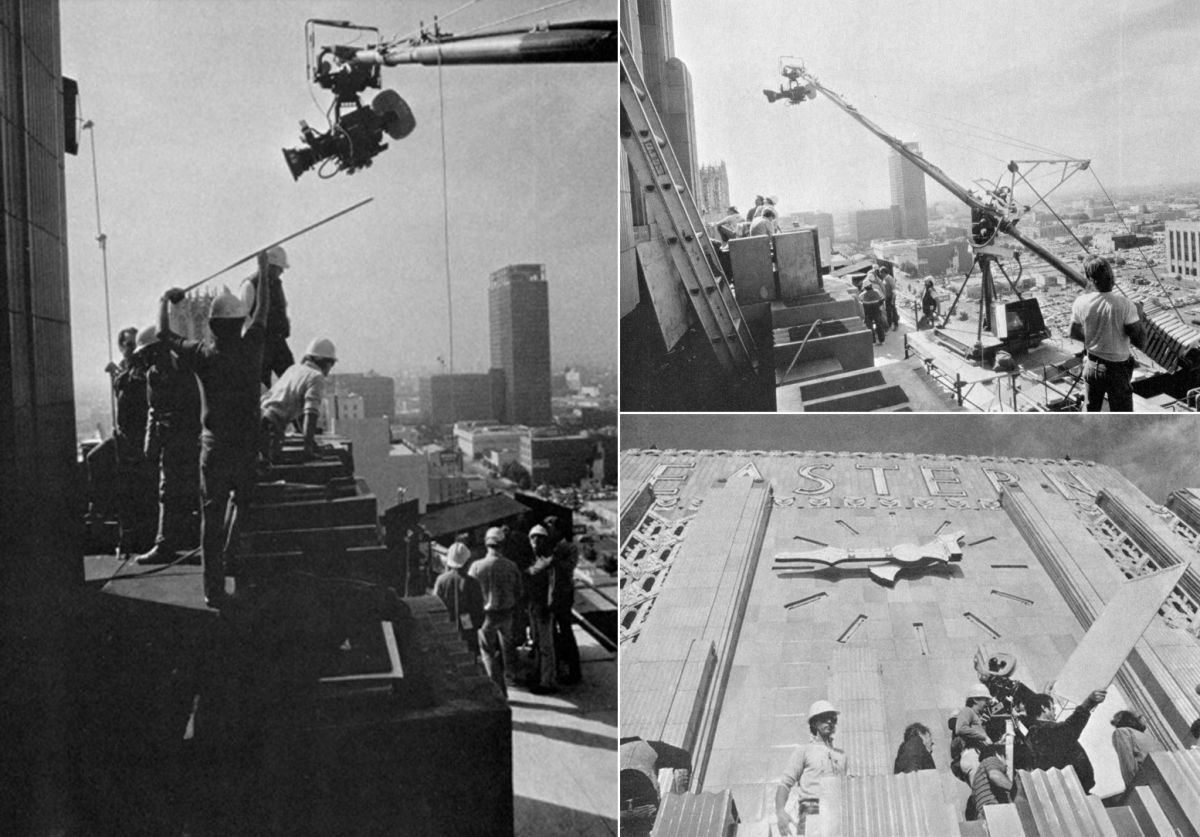

The main location was the Aquarius Theatre, in Hollywood, a monstrous interior. “We tore it apart, aged and rebuilt it,” says Finnerman.

Finnerman tested both Eastman Plus-X and Double-X films. “I would have needed more than 300 foot-candles to shoot at stop T/4 with the Plus-X film, he Above: On location above downtown L. A. Left: Three cameras are used in photographing the many in-car scenes. says. “That just wouldn’t have been practical.”

Double-X film is rated for an El of 200, but Finnerman found that it tested well at 400... “I couldn’t see a real difference,” he says. “It was just a marginally flatter look.”

He shot tests with 25 foot-candles of key light, and pulled good depth at stop T/2.8. Fortunately, the theater had a dimmer lighting system covering the stage where band scenes were filmed.

“The panchromatic film doesn’t see Kelvin, so using the theater lights was no problem,” Finnerman explains.

That allowed him to spot his fill light on scaffolds. “We did that to create dimension,” he says.

The vast interior had a basic key light level of 15 to 20 foot-candles, and Finnerman worked mainly at stop T/2.3.

In order to develop two contrasting lighting styles, Finnerman and the producers spent a lot of time looking at old MGM and Warner Bros, movies, including Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon, A Streetcar Named Desire and Mildred Pierce.

“I remembered Harry [Stradling, Sr., ASC] telling me to take the light around until it scares you when shooting low-key black-and-white scenes.”

“We settled on A Streetcar Named Desire as a model for Cybill’s dream, and Casablanca for Bruce,” he says. “Then, I forgot all of the rules about shooting color. I remembered Harry [Stradling, Sr.] telling me to take the light around until it scares you when shooting low-key black-and-white scenes. I did everything but front light, except for a dance number that Cybill did and that was front-lit. We used cross and backlighting to create dimension.”

In contrast, the Willis dream was more guttural. Finnerman used light and shadows to create halftones, and double fog filters to manufacture the illusion of grain, a more down-and-dirty image.

The differences were very subtle; something that viewers were more likely to sense than see. Most of the time, Finnerman was running two or three cameras for coverage and five on the musical numbers. The biggest problem was separating the walls. “They were hot,” he says. “I hung just about every light that we had. MGM Labs did a great job... they gave us just the right gamma for each of the two versions.”

For Cybill’s song numbers, Finnerman used the netting that he saved from My Fair Lady, which flared reflected light from a necklace she was wearing. This created a similar effect to a star filter.

“She’s a bubbly personality with a great voice,” Finnerman says of Shepherd. “It was easy to imagine that you were there in the mid-’40s, and she was a songstress with a dance band. I think she looks even better in black-and-white than color. And Willis, he’s a young Bogart.”

What makes Moonlighting so special? “In a way, it reminds me of Star Trek,” Finnerman answers. “Viewers are fiercely loyal. Working on this show is like belonging to a special club.”

It also proves you can create good television without committing mayhem. “Violence on TV is depressing,” Finnerman observes. “You only get a couple of fleeting moments here on Earth, and I want to do something good in that time. “I’m not a purist, but everyone has to make a stand someplace,” he continues. “Working on the production of an episodic TV show entails long, hard hours, and it can be very stressful work. If you are going to put yourself through that, you might as well be doing something which you can be proud of.”

“You have to remember, in the end, people are going to come to you, and if something was less than perfect, you can’t blame it on the camera, lens, film or the operator. You’re the one they picked to do the job right. It’s your responsibility.”

In recent years, Finnerman had mainly worked on TV movies and mini-series. Why put himself through a grind like Moonlighting? “I couldn’t be happier if I had just shot Out of Africa” he says. “I look forward to coming to work everyday. I believe that we have done something special — the cast and crew are very much a family.”

Bill Clark is Finnerman’s operator, and Bill Loranger and Mike Stradling are assistants. The second unit is headed by Roger Shearman; the operators are “Chuy” Elizondo and Dick Thorpe, and Joe Valentine handles the Steadicam image stabilization device used on locations.

“My key grip, Walter Cripps, was my dad’s key crab dolly man,” Finnerman notes. “We’ve been together almost from the day I started as an assistant, 32 years ago.”

Finnerman directed the final episode of the current season and is slated to direct some shows next year. “I’m looking forward to that,” he relates. “Earlier in my career, when I was at Universal Studios, I directed several episodes of Night Gallery. I remember that I directed one episode starring Leonard Nimoy. Later, he directed an episode that I was shooting. That was an interesting experience. You can learn some important lessons by occasionally stepping out of your normal role.”

One of the things he has learned is that on Moonlighting or any other film, ultimately you are lighting to please yourself, rather than 20 or 30 million viewers. Of course, this occurs within the parameters of the show and the obligations you have to the producer, director and cast.

What advice would he offer to a youngster breaking in?

“Never be lazy,” Finnerman answers. “Try to be creative. Anyone can bounce light for exposure or to get a soft look. To be different you need to learn what happens when light strikes a particular emulsion. How can you bend the film to get the most out of it during a particular situation? You can work with and stretch your film. If you are having a good time, you are probably doing good work.”

Of course, there are some things you are born with. “I’m a very visual person,” says Finnerman. “I read a script, and I draw pictures in my mind of what the scene should look like. I envision every nuance of light, and I can tell you then whether the key should be 10 or 20 foot-candles.

“But, you can’t sit in your chair on the set. You have to be thinking and looking every second. I’ll move that scrim here, and turn that light off, and another one on, and add a little color until everything falls perfectly into place. I am a great admirer of Joe Biroc [ASC], who works this way.

“Most of all, you have to remember, in the end, people are going to come to you, and if something was less than perfect, you can’t blame it on the camera, lens, film or the operator. You’re the one they picked to do the job right. It’s your responsibility.”

Finnerman earned an Emmy Nomination for “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” in the Outstanding Cinematography for a Series category in 1986. He spoke to the Archive of American Television in 2002 about shooting the episode:

He was nominated again in 1988 for the Moonlighting episode “Here’s Living with You, Kid.”

He passed away in 2011.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.