Shot Craft: The Art of On-Set Still Photography

The BTS photographer must be a true ninja — you should not be seen, heard, smelled or even sensed by the talent or crew around you.

The cinematographer, in control and at the top of their game, oversees the capture of a complex shot. Two actors play off of each other with an energy that typifies their characters’ unique bond.

You might assume that any talented photographer who understands the filmmaking process can take great set photographs like these.

Not true.

Behind-the-scenes photography is an art unto itself. It’s also a job that many young cinematographers gravitate to because it’s an opportunity to get on set, be part of the crew and work with a camera. If you find yourself in that position, here are some things to remember.

Be Invisible

The BTS photographer must be a true ninja — you should not be seen, heard, smelled or even sensed by the talent or crew around you. The best of them can be standing right next to you for 10 minutes before you’re aware they’re there.

This means your camera must be silent. In the film days, set photographers had to blimp their cameras, but many of today’s digital cameras have a silent mode. Your camera cannot “click” as you take a photo, especially because you’ll be shooting actors during rehearsals. Your lens must be silent as well. Some autofocus still lenses have loud motors. Choose wisely.

Being invisible is critical, because the job of the BTS photographer is, generally speaking, intrusive. It can be distracting to all who are being captured. Yes, the actors are used to the camera, but they’re used to the production camera, and having an additional lens on them can feel overwhelming — like they’re never getting a break between shots.

As for crew, many of them are behind the camera for a reason, and being photographed can make them self-conscious. There’s also a really fine line here: You can’t intrude on someone’s privacy — and capture them in non-professional light — without their permission. If production has done its job, the crew have all signed release waivers granting permission for their photos to be taken while they’re working, but if they’re having a private moment, don’t shoot them.

Read the room. Creatives are passionate people, and filmmaking can be a high-stress endeavor. Tempers can flare. Personalities can clash. That’s the time to step back and disappear. BTS photography is intended to promote and sell the project. You’re not there to document every moment, especially the awkward ones. You want to capture moments of strength, positivity and triumph. If a key member of the production is having a bad day, it might be best to wholly avoid them that day or return to the set on another day altogether.

And this should go without saying: Never, ever use flash. Ever.

“You’ve got to move fast to get these moments. Keep a keen eye on what’s happening and plan ahead as much as you can. If you’re paying attention, you will often know what’s going to happen next.”

Be Prepared

Know the script and the shooting schedule — know what’s being shot, when and where. The unit production manager, line producer or 1st AD can give you the schedule. You’ll need to know it inside and out. Production will probably limit your days on set for financial reasons, so choose your days wisely. (Production may actually dictate your days, but don’t be afraid to speak up if there are other days you think are important.)

But this doesn’t mean to only show up on days when big explosions are happening. It’s your job to have an idea of how to capture the best representation of the whole production — which also means being familiar with the script. Which story moments are key? And which ones are spoilers? What are the big set pieces? Your photography should include samples of each major location, each major set, all the major moments in the script and any scenes that are complicated to execute.

Also know which setups are not good to shoot. A love scene isn’t necessarily a good day to show up unless you’re specifically requested. And the second, third and fourth days of the same 15-page dialogue scene probably don’t require your presence, either.

If multiple units are shooting simultaneously, it can be tough to know where to be and when. The AD is your best friend here. Stay in close communication with them, but understand that they have 10,000 things to deal with, and you are just one of them.

Be prepared with your equipment. The film may be beautifully lit, but the milieu behind the camera won’t be — it’s quite often horribly lit. It behooves you to have a highly sensitive camera and very fast lenses for capturing these moments. Yes, you can shoot with slower frame rates, but your work is useless if it all has motion blur in it. Don’t overestimate your ability to handhold a camera at slow frame rates!

The rule of thumb is a minimum shutter speed “equal” to the focal length of the lens. So, if you’re shooting with a 100mm lens, don’t ever shoot below 1/100 of a second. If you’re shooting with a 25mm lens, you can slow down to 1/25 of a second.

Your Shot List

It’s also your job to simulate what the production camera captures and get those “hero” moments that represent the film. (Even in this era of high-photosite cinema cameras, your still camera is usually even higher, so it’s your images that production relies upon to provide clear, crisp representations of the filmmakers’ work.) These moments are generally captured during camera rehearsals, when the lighting is set and the first-team actors are working the scene. (This is also where silence is critical.) You want to emulate the production camera as closely as possible, including camera settings of ISO, white balance and aperture — and the field of view.

In some instances on some productions, you can tuck in on the “dumb” side of the camera right next to the lens and grab shots, but this might be verboten. It depends greatly on the operator, assistant, cinematographer and situation. When this isn’t possible, it’s best to be behind the production camera on a slightly longer lens, capturing a close approximation of the field of view of the shot.

Get those powerful moments of the actors doing their work! Imagine what the trailer for this production might look like and create the still frames from that trailer with your camera. The more emotional or intense the talent is, the more powerful the image will be. That doesn’t mean quiet, still moments aren’t good, but grab these hero shots.

Depending on the director’s style, there might not be a camera rehearsal. In that case, it’s your job to shoot during a take, which is generally frowned upon. Do it in the early takes and then fall back. Your ninja skills will be put to the ultimate test in these situations. Be aware of all the components required to execute the shot, and don’t get in the way of any crew doing their jobs.

Also, shoot both landscape and portrait mode of everything you photograph. If you only shoot landscape (horizontally), then your work will be of limited use. Adding portrait opens the door to a lot more possibilities. Consider that your work might end up on the poster — or on the cover of this magazine!

Find the Story

Here’s where the real art comes into play. What and how do you shoot in order to capture the work happening behind the camera?

First, tell the story! Imagine you are shooting a movie about the making of the movie. Who are the “lead characters”? How do you tell the story of what they’re giving the audience? Make sure every shot you take has a clear subject. A big wide shot of the whole set is helpful sometimes, but it can also be a waste if there’s no clear subject and focus.

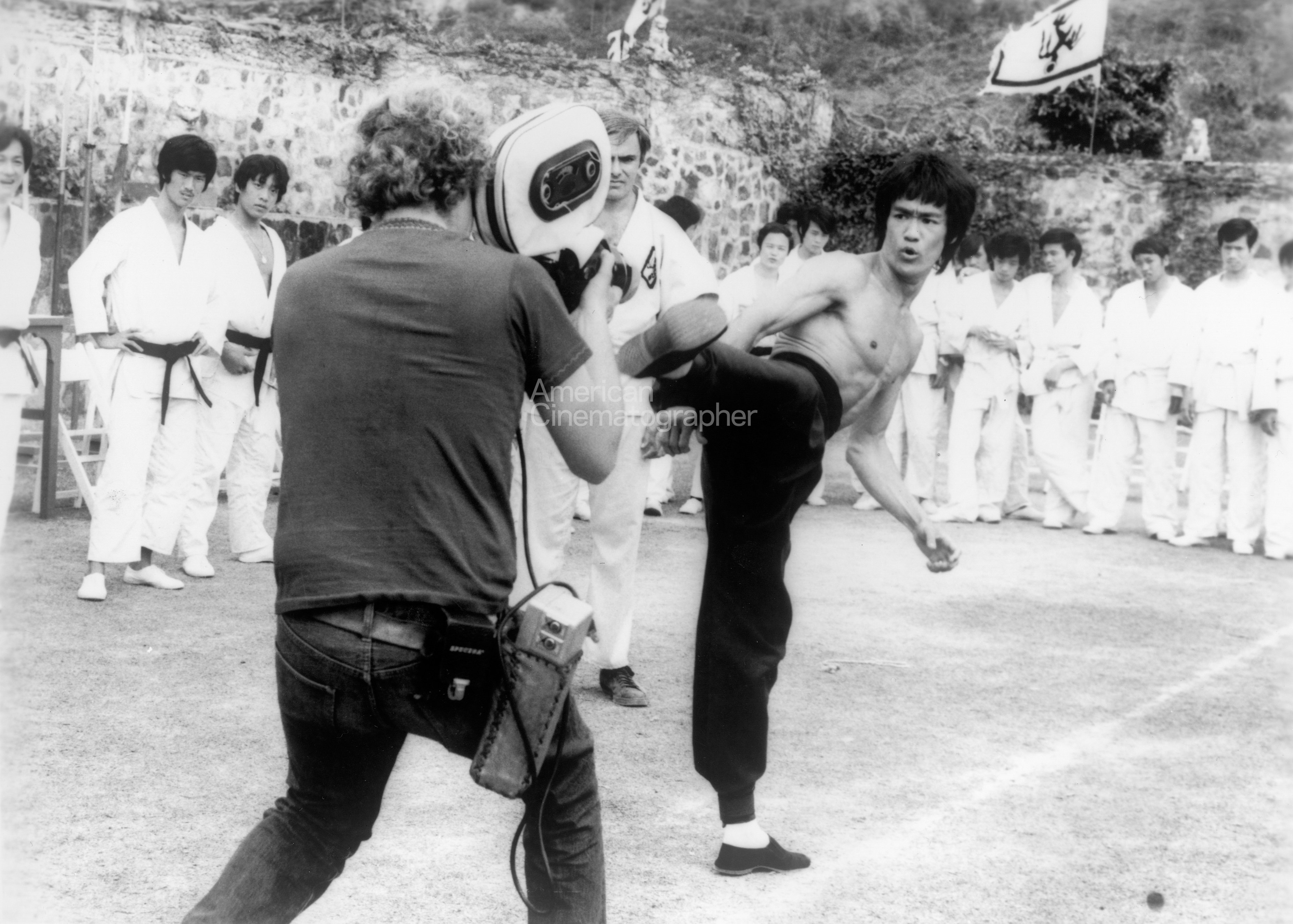

What’s happening with any given setup? There’s often a “star” for each moment of production — it could be the stunt coordinator and their team working with an actor or a stunt double, or grips building a special platform that will make the actor appear to be suspended in air. Find what’s special about this moment and tell that story in your photographs. Remember that “art photos” are significantly less important than ones that clearly tell the story and feature the prominent individuals and gear — though a clear story plus artistic composition can yield an epic BTS shot.

Capture interactions. Get the director talking to actors, the director with the cinematographer, the cinematographer with the gaffer, the production designer with the art director. Imagine you’re shooting a movie about them. Show faces. Concentrate on the human. Two- and three-shots are important, but so are over-the-shoulder close-ups.

Just make sure you’re paying attention to the dynamics of the interaction and getting proper coverage. If it’s the director talking to the cinematographer, get that closeup OTS of the director’s hero and then quietly move around to get the cinematographer’s OTS.

You’ve got to move fast to get these moments. Keep a keen eye on what’s happening and plan ahead as much as you can. If you’re paying attention, you will often know what’s going to happen next.

Spread the Love, Capture Achievements

It’s important to get every crewmember “in action” doing their job. You want the cinematographer at the camera — or checking the light, or otherwise prepping a shot — and the director giving direction, especially when it’s their spotlight moment. If there’s use of prosthetic makeup, get the makeup artist on set touching up the actor. If there’s a big move to a set, capture the production designer interacting with their team. If there’s an elaborate dolly move, get that dolly grip at the height of their concentration.

And along with these hero shots, make sure to also capture what it is they’re accomplishing. Where are they? What scene are they working on? Why are they doing what they’re doing? (If it’s the cinematographer who is captured in a photo like this, and AC ends up covering the production, the image will make the editorial team’s day!)

Take close-ups and/or hero shots of every member of the crew at least once and every department head at least half a dozen times. Keep in mind that some departments are removed from the main set, especially makeup, hair, wardrobe, props and production. (Don’t forget the people in the office!) The sound mixer is often a ninja, too, but don’t forget them.

Get the call sheet every day and check off the individuals you’ve photographed. Make sure that by the end of the show, you’ve captured everyone.

The Devil in the Details

The particulars matter. Get a hero shot of the cameras; lenses; lighting; grip equipment; makeup, sound-mixer and prop kits; and so on. If it has a company label on it, get a shot of it. You’re going to have more time than you think you will, so take the time to get these shots. Avoid hanging around craft service and go after these details. The many companies that support the film industry thrive on these photos — especially shots of crew actually using their equipment — and it helps the production in innumerable ways.

Look at what it takes to accomplish every setup you’re photographing, and capture the individuals involved and the tools they use. It’s all part of the story. Tell that story with your photos and your work will be invaluable.