CinemaScope and Stereophonic Sound: The Big Changeover

When 20th Century-Fox studios decided to abandon conventional filmmaking in favor of CinemaScope productions exclusively, it meant making many changes in equipment, procedure and techniques.

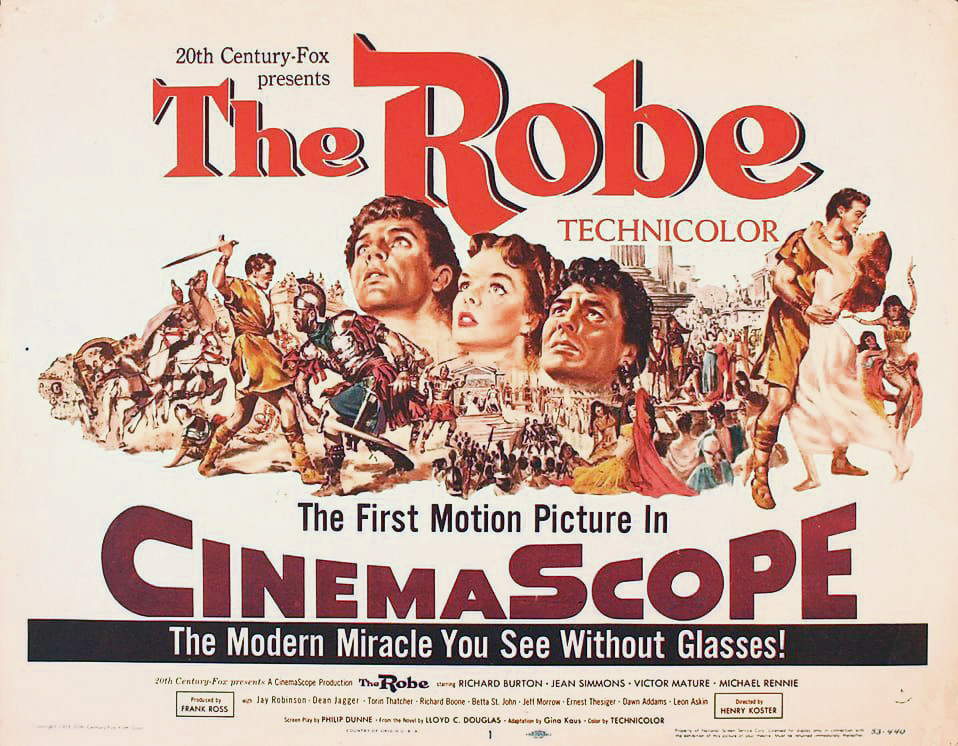

When theater curtains opened last month to reveal CinemaScope and its first vehicle, The Robe, produced by 20th Century-Fox, millions of Americans were greeted by two of the most momentous and inspiring events to happen in the motion picture industry in more than 20 years.

The release of The Robe has come after more than 10 years of untiring effort and preparation by the studio, and is almost unanimously considered to be the greatest motion picture of our time. Directly contrasting the many years which have gone into The Robe is the story of CinemaScope. It is a short story — less than 10 months old — but it has already been written in indelible ink on the history pages of the motion picture industry, thanks to the vision and foresight of Spyros P. Skouras, president of 20th Century-Fox, and Darryl F. Zanuck, vice-president of the company in charge of production, both of whom immediately saw the potentials of this new medium.

CinemaScope is a new horizon in motion picture technique. Technically, it is the greatest development since the introduction of sound 25 years ago. And it has represented as great a challenge to the technicians and artists at Twentieth as did the introduction of Movietone at the studio in 1927.

The story of Twentieth’s conversion — the “big changeover” — to CinemaScope is an unusual interesting one because it reveals how one of the industry’s biggest studios suddenly changed its whole course at a time when the industry was in the doldrums, and in face of dire warnings that such a move simply wasn’t possible. The story is further important because the unprecedented success of CinemaScope portends similar moves by other studios.

The studio’s first manifestation of the revolutionary French panoramic screen process came in January of this year when its Camera Department received one “Dr. Chrétien” anamorphic lens. The first probings at the new medium consisted of photographic tests. To screen and evaluate these, a makeshift projection room was built on Stage 6 of the Western Avenue studios. Here a giant, curved screen 63' wide, having a new-type reflective coating was installed. It was planned originally to carry on a program of tests and proving of the anamorphic lens for a period of six months or more. However, after Mr. Zanuck saw the first tests screened, he decided to photograph The Robe in this new medium, starting as soon as possible.

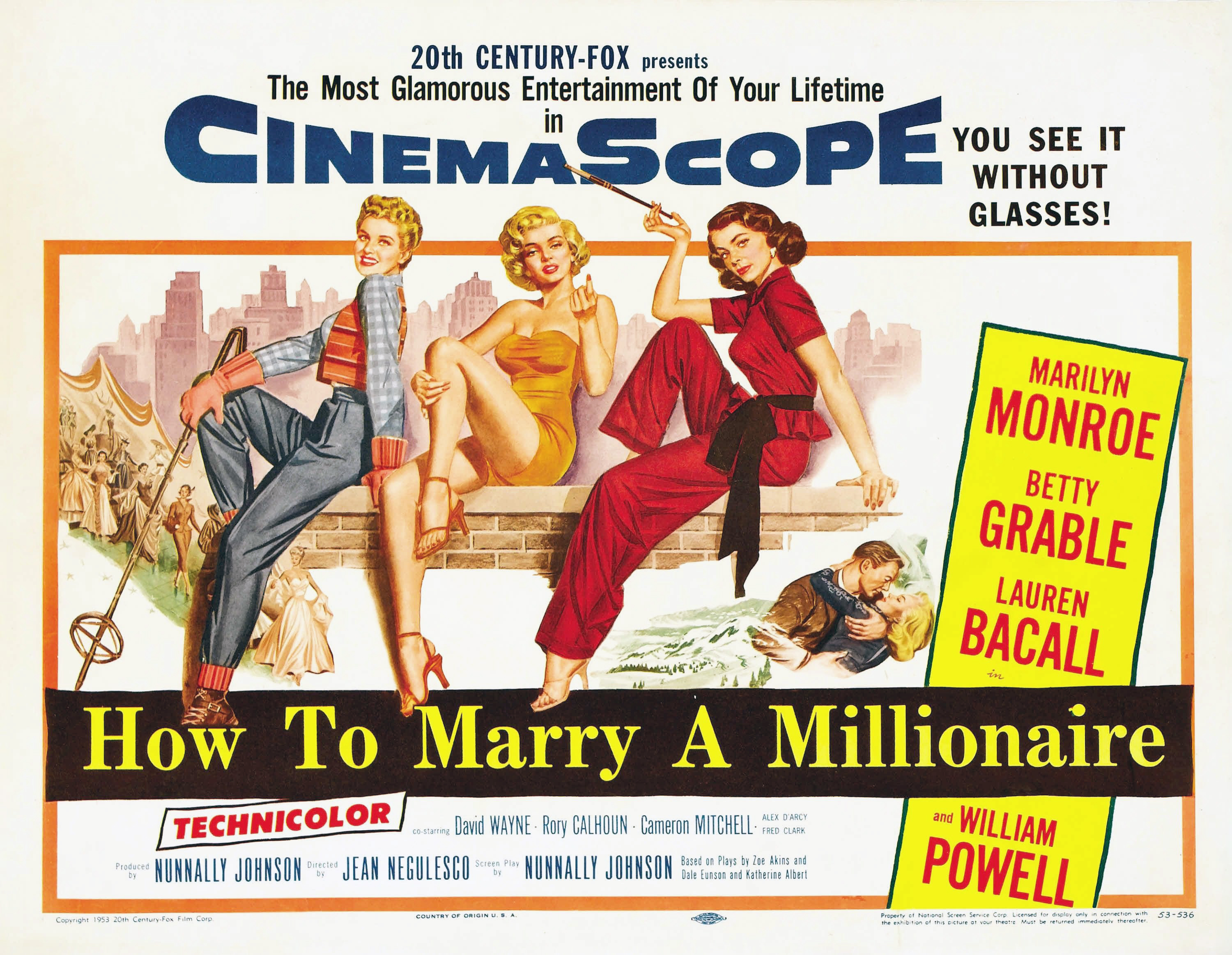

The entire CinemaScope program of the studio’s camera department was conducted under leadership of Sol Halprin, ASC — head of the department. The first real production tests were made of actual scenes and sets of The Robe. When the second French anamorphic lens was received by the studio, it opened the way for production of a second picture in CinemaScope. As actual production photography on The Robe began, How To Marry A Millionaire was being readied to go before the second CinemaScope camera.

The significance of the studio’s decision to convert all production to CinemaScope was felt immediately. It affected procedures in almost every department related to production. Involved immediately in changing to the new CinemaScope technique were those employed in cinematography, set lighting, film editing, and sound recording. Early tests indicated several changes in design of the anamorphic lens would greatly improve photographic results as well as simplify use of the lens in production photography. For one thing, the original French lenses were in square mounts and required unweildy apparatus to hold them before the cameras. These had very crude follow-focus attachments on them. All this meant that special methods had to be devised to hold the anamorphic lenses so they could be mounted properly before the studio’s cameras. Before long plans were set in motion to have the anamorphic lens re-designed and mounted in a conventional barrel-like housing. This task was given to Bausch & Lomb Optical Company. Before the end of April, five of the improved CinemaScope camera lenses were delivered to Sol Halprin.

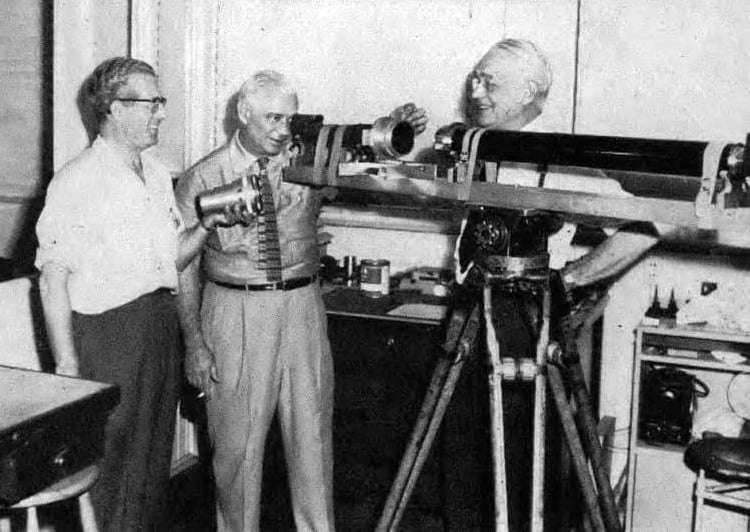

Prior to this, technicians in the studio’s camera department spent many nights checking and re-checking the calibrations on the original two anamorphic lenses that were being used in shooting the initial CinemaScope productions. Special types of telescopes had to be purchased so that the Camera Department could check the lenses for quality of focus and calibrations, to make sure the calibrations were holding up, and at the same time to determine if anything could be done to aid and improve sharpness of focus.

The studio’s Camera Precision Machine Shop staff had to go to work immediately building new holders and designing new matte boxes. It had to design means and methods of using the conventional finders of the cameras in order to get the extremely wide-angle view that the anamorphic lens yields; and this all had to be ready in time for use in the photography of three CinemaScope pictures — Beneath The 12-Mile Reef having now been added to the schedule of CinemaScope productions.

As difficult and complex seemed the problem of converting to CinemaScope, this was only half the story. CinemaScope had a complementary new feature, sterephonic sound, which in one sense posed a more involved conversion problem to the Sound Department than did CinemaScope to the Camera Department. Whereas the Camera Department was able to use standard photographic equipment in conjunction with the CinemaScope lens, the Sound Department was confronted with the task of redesigning the entire sound recording system to a multiple-track system. Like CinemaScope, the sound conversion program began early this year. Local directorship of this program was undertaken by Sound Department head Carl Faulkner and sound development technician Lorin Grignon, with the overall sound conversion being supervised by New York technical director Earl Sponable.

First step was the development of a magnetic sound recorder and mixing panel which would handle three or more separate sound channels. Where one track carried all the dialogue before, three individual tracks would now be employed for dialogue. In conventional sound recording, the soundtrack ran along the edge of the 35mm film strip.

Where would there be room for three or four soundtracks? Here was the answer: It was obvious that there wouldn’t be enough room for multiple soundtracks on the film strip as it was. The only variables were the sprocket holes and the picture itself. By cutting down the width of the sprocket holes and by cutting the aspect ratio from 2.66-to-l to 2.55-to-l, two soundtracks could be placed on either side of both rows of sprocket holes.

Because of the problems involved in multiple photographic soundtracks, it was obvious that magnetic sound recording would be the only feasible method for stereophonic sound release. Now, a practical method for “striping,” or laying the several soundtracks on the picture film, had to be devised. The final details of this operation have been worked out, so that highest fidelity magnetic tracks can be placed on the film strip to ensure top quality sound reproduction on all tracks.

To be sure, there were many things to tackle in the development of a multiple-track sound system. By production necessity, one of the first was the design and construction of a sound recorder, for putting dialogue on three separate tracks simultaneously. The first triple-track recorder designed for recording and playback was seven feet high and weighed 600 pounds. Although it was good from an operational viewpoint, it was impractical because of its great bulk. So the next problem was to put all the components of stereophonic sound recording into a more practical and portable form. This development was carried out swiftly and effectively, the new triple-track recorder being every bit as compact and portable as the former single-track recorder. It was a project which required two and a half weeks of intense research and design, night and day. Yet it represented only a small phase of the Sound Department’s job of converting to stereophonic sound. In effect, the entire sound channel (all the equipment necessary to handle the various steps of sound recording and reproduction) had to be rebuilt for stereophonic sound. Not only was this a monumental task, but it was one which had to be accomplished in an amazingly short time, so the new system could be used in the entire CinemaScope program and so theaters could gear for stereophonic sound.

By the nature of the principal involved, the intermediate CinemaScope image is greatly distorted. This fact presented a problem to the film editor, who views all footage in the Moviola in order to edit it. The CinemaScope scenes were squeezed out of proportion to the degree that the cutter was unable to select and match scenes with any degree of accuracy. This meant that some sort of compensating lens would have to be adapted to the Moviola so that the film editor could view scenes in their normal proportion. An additional “fly in the ointment” was the fact that several different types of Moviolas are in use on the lot. Different types of lenses would have to be designed for each type of Moviola. The Precision Machine Shop went to work and developed lucite lenses which, when placed in front of the Moviola viewing area, unsqueezed the picture so it had the normal CinemaScope look. New lenses had to be built for the projection-type Moviolas used by shooting companies for picking and matching action on the set. These were built so that the Moviolas could throw a CinemaScope picture onto a small screen.

Also being built by the Camera Department is any entirely new type of finder which will encompass the wide angle of CinemaScope and will give the cameraman good, clear viewing on the set. The first prototype is nearly completed and will be tested soon. Camera personnel itself has played a tremendous part in the pioneer work that marked the earliest days of CinemaScope photography. Cameramen, operators and assistants, through their ability and enthusiasm, have mastered a heretofore unknown technique almost overnight.

Since projection is a necessary complement to photography, all of the camera changes resulting from the conversion to CinemaScope have been accompanied by changes in projection technique. Most important of these, of course, is the compensating anamorphic lens which, when attached to the projector, returns the squeezed scene to its original proportion. To accommodate the new triple-track sound system, projectors had to be equipped with a new magnetic sound reproduction head. This reproducing head was a development of Earl Sponable and his New York research staff and the sound department.

The installation of new sprockets for exact registration with the new smaller sprocket holes has been completed on several of the studio’s projectors.

A 31-foot Miracle Mirror screen has been set up in projection room 1. Projection room 5 has a 22-foot picture and Mr. Zanuck’s projection room has a 17- foot picture. Stage 2, which is the new re-recording stage, has a 42-foot picture as well as two special screens on Stage 1 for the Music Department. Projection room 3 has a 26-foot screen and six of the studio’s regular projection rooms are being equipped to handle CinemaScope pictures. All projection changes have been supervised by Sol Halprin and Chief Projectionist Bill Weisheit.

Equipment used by the Special Photographic Effects Department under Ray Kellogg and the Optical Printing Department under Jim Gordon have undergone numerous changes. New types of mounts have been built, and many methods have been devised to fit the mounts onto the many types of camera set-ups that these departments employ with the new anamorphic lenses.

The Electrical Production Department has very definitely been affected by the new dimensions of CinemaScope. Naturally, there is little additional lighting problem for outdoor scenes photographed in the new medium. But in the case of large interior sets which had to be lit artificially, there was a problem. The greatly expanded range of the camera equipped with anamorphic lens prevented electricians from moving their lights in as closely as they could in conventional photography. This meant that larger units had to be employed to compensate for the light loss incurred by the greater throw. In addition to this new obstacle, the fact that often in CinemaScope greater areas have to be lighted for larger scenes has put additional requirements on the Electrical Production Department for more and more light.

In one sense, the conversion of the Moviolas used by the Cutting Department has been a problem of the Camera and Sound Departments. But the Film Editorial Department has had many other obstacles to overcome. The single strip Eastman color film that is used with CinemaScope is a thicker stock than the magnetic sound footage. Since film editors use the double system when editing (picture on one track, sound on another), the problem arose of the picture reel and sound reel being of different sizes. In other words, a 1,000' reel will hold 1,000' of sound track but only 800' of picture, because of the greater thickness of the latter. This presented a problem wherever the two tracks had to be rewound together. It was solved by employing a clutch on the sound reel to slow it down to the speed of the picture reel.

Many other operating adjustments have had to be made since the first reel of CinemaScope footage reached the cutting rooms. All of these adaptations to the new medium have been accomplished without delay, at minimum cost. According to Jerry Webb, head of the Cutting Department, CinemaScope has a terrific asset over conventional photography, from the cutter’s point of view. The wide range of CinemaScope scenes tends to eliminate over-cutting. The result is a smoother product, with less cuts than were required by the old system.

Contrasting the radical changes that many departments have undergone in the conversion process, a few production departments have had to alter their operating procedure very little due to CinemaScope. For example, supervising art direct Lyle Wheeler reveals that his department has been virtually unaffected by the transition to the CinemaScope process. For instance, the interior tent scenes in The Robe were originally designed for conventional photography, yet the set was not altered at all. In the case of larger sets, the shapes have been changed slightly to conform to the new aspect ratio, the emphasis being on width. This change in picture frame proportion is an advantage to the Art Department inasmuch as it eliminates the necessity for many of the matte shots that would have been required in the old system. So the conversion to CinemaScope by the Art Department has been a natural and most advantageous one.

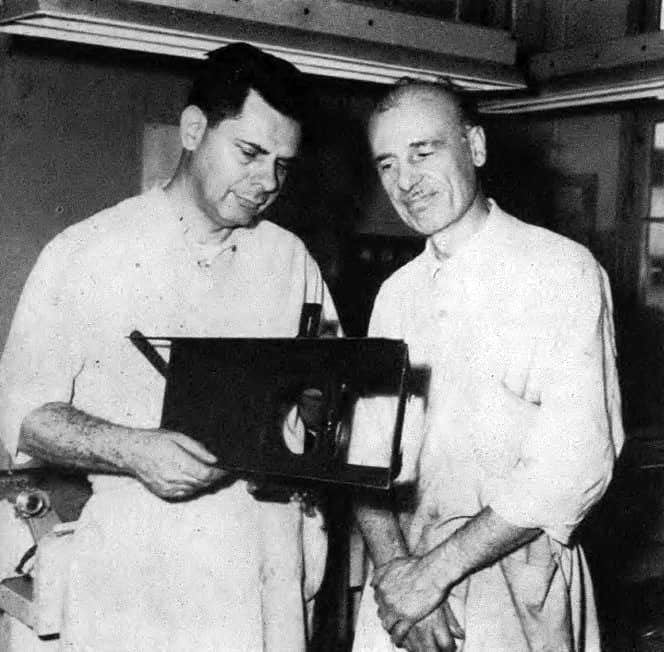

tests with the CinemaScope lens and later photographed The Robe — discusses the first anamorphic lens

imported from France with TCP studio's technical

director, Earl Sponable.

To the director, CinemaScope offers a great new opportunity for expression. No longer will he be limited by the proscenium. Coupled with stereophonic sound, his visual and aural selectivity are greatly augmented.

To the actor, CinemaScope provides a more solid basis on which to display genuine acting ability. By the same token, its requirements of the actor are far greater than were those of the conventional medium. The actor in CinemaScope is often required to do entire scenes without a break, much like the technique employed in stage acting. This means that the actor must memorize more lines and must have a greater understanding of the character he is portraying. In repayment for this extra efort, the actor has the satisfaction of “living” his part not fragmentarily but completely, thus yielding a greater performance.

To mention 3, 6 or 20 of the studio’s departments in the conversion to CinemaScope would be far from the whole story. For in one way or another, every department and person on the lot has been affected by the introduction of this new medium into production technique. Whether the individual transition has been great or small, it has been an important part of the overall conversion.

To name all the heroes in the story of CinemaScope would be impossible here. It is the result of the combined effort of specialists in many fields, all of whom felt that the challenge of CinemaScope could be met.

You'll find much more on technical advances and various other widescreen systems introduced in the 1950s here. And here is a brief history of widescreen in motion pictures.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.