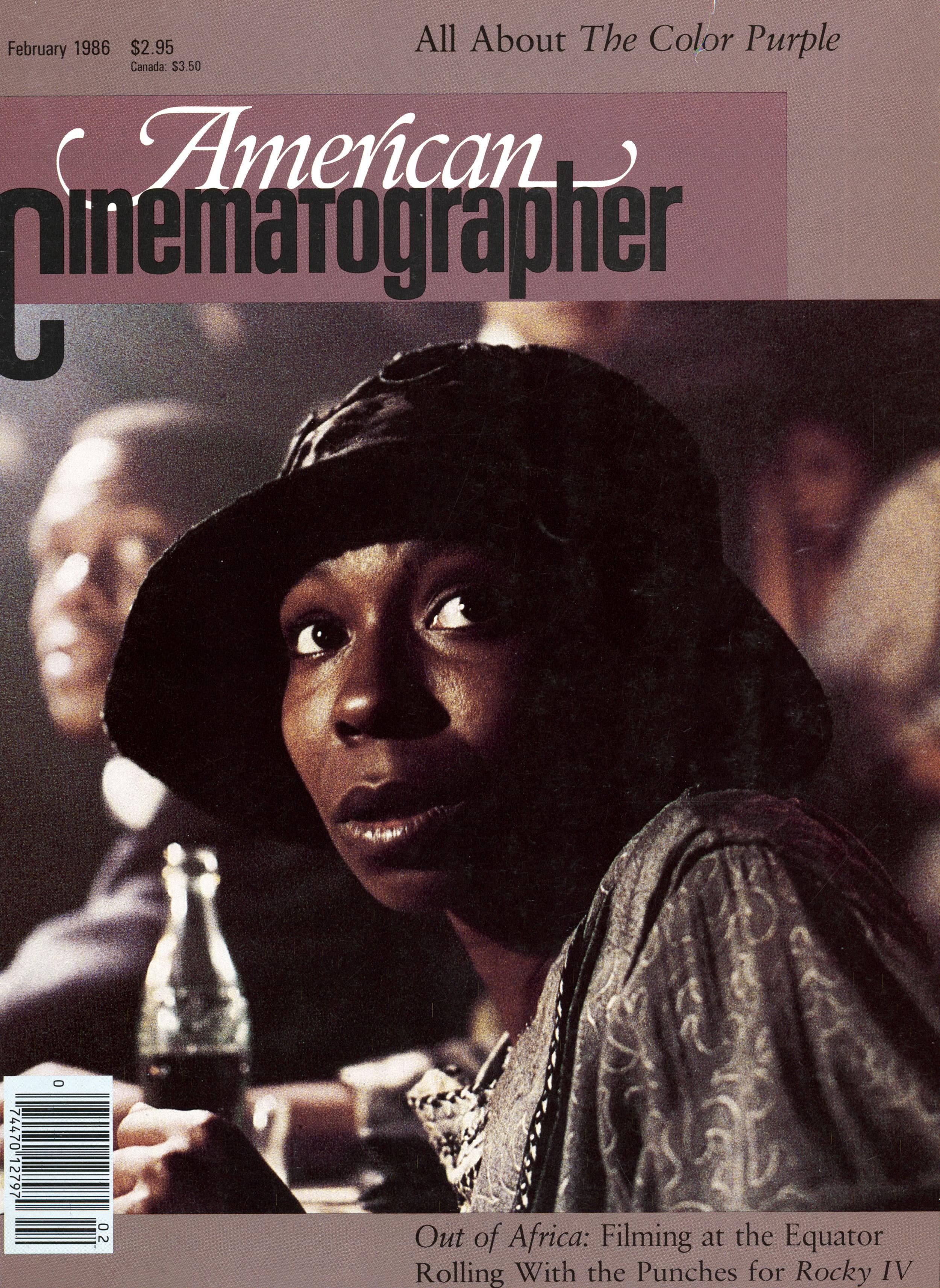

The Look of The Color Purple

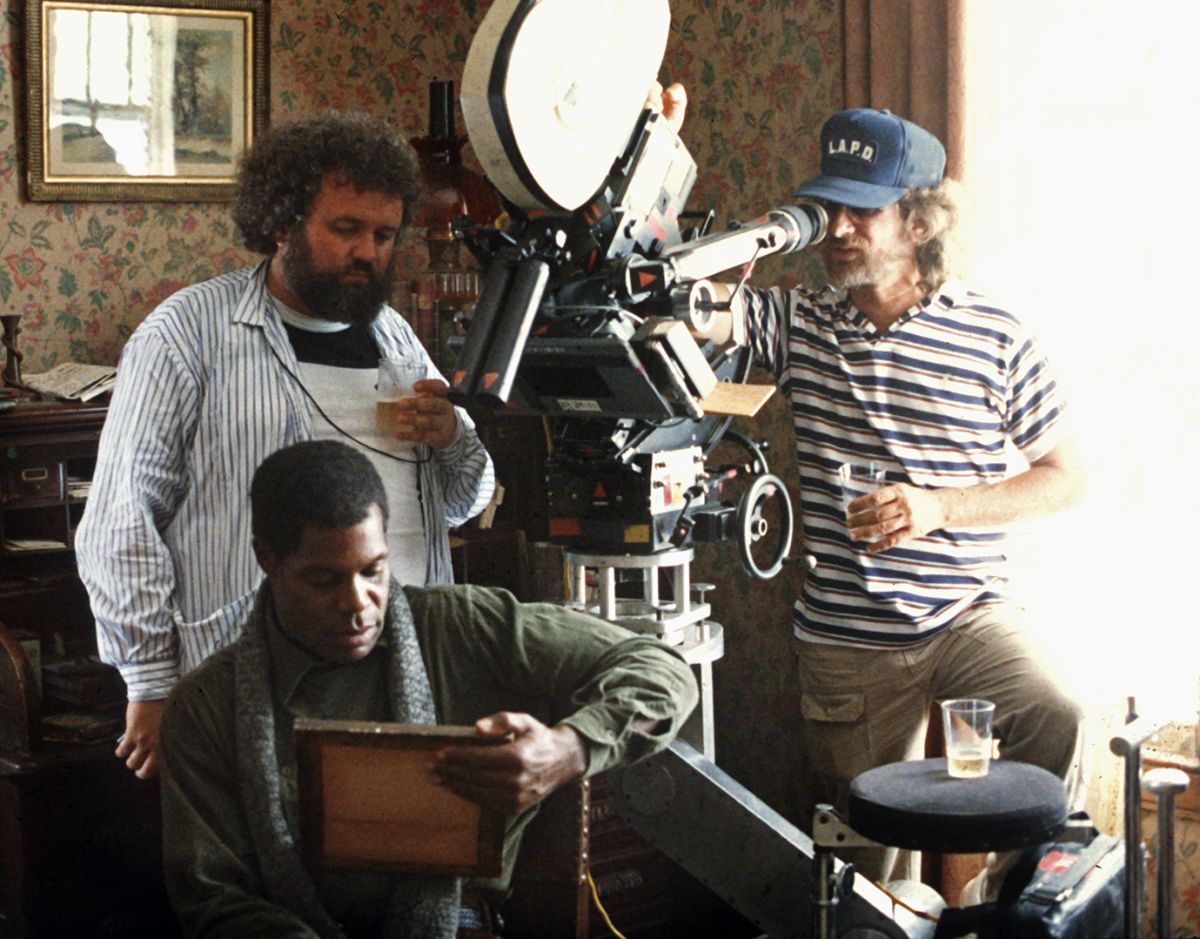

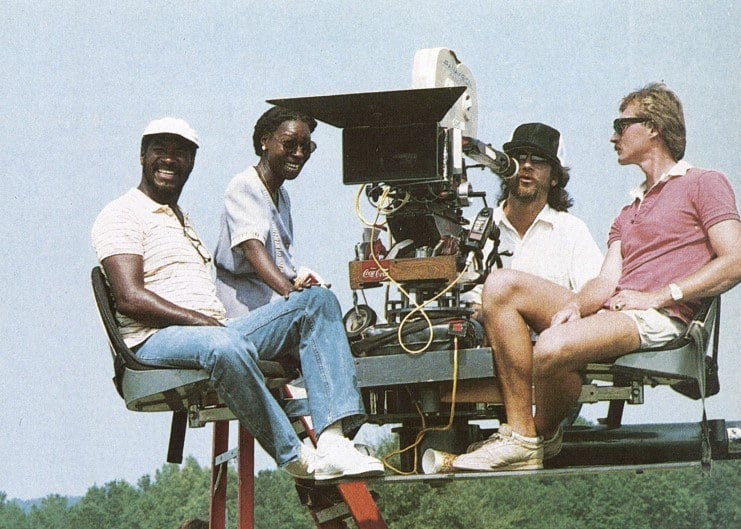

Allen Daviau details his photographic approach to this striking period drama directed by Steven Spielberg.

It isn’t very often that a great book is successfully translated into a film. Too often the author’s intent and sense of storytelling is subverted in the translation, either because the filmmaker couldn’t find the cinematic diction and technique to match the literary diction and technique, or because the filmmaker bends the story to whatever the current Hollywood whim dictates.

If the book being translated has the substructure of poetry — a sort of elusiveness that sets off emotional and intellectual depth charges in the readers consciousness, then the task of making the film as a translation is compounded.

So, when Allen Daviau was assigned to photograph Menno Meyjes’ adaptation of Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Color Purple, he and the film’s director, Steven Spielberg, were going to test their skills not only as movie makers, but also as storytellers. They were testing themselves minus the technological safety net of special effects that Spielberg has employed for over a decade.

Early on, Daviau realized that “so much of this film is a piece of storytelling; and we have an enormous story to tell. The photography had to serve the clarity of the storytelling first. This ranks first along with the delineation of these characters that you’re going to live with for more than 30 years of the story.”

In the 30 years that both the book and movie span, Walker tells the story of Celie, a black girl who grows into a woman who discovers not only her sexuality, but also her own inherent strength of character through her involvement with Shug Avery, a blues singer. This odyssey of self discovery is charted first in a series of childlike letters to God, that contain a spare, aching sense of poetry; then in a series of quietly raging letters to the sister that she was separated from, when she’s “given” in marriage to the haunted and embittered Mister.

Mister loves Shug Avery, but is forced to take a “decent” woman as his wife by his tyrannical father.

The letters also chronicle, as does the film, the wary, but mutual, stirrings of respect that both Celie and Mister begin to realize in each other. Celie is played by humorist and actress Whoopi Goldberg and Danny Glover plays Mister.

As in all Spielberg films, the quality of light is used both to define environment in the story and to sculpt character. Daviau and Spielberg like to use light almost as an actor, allowing it to shape a scene almost as much as the actors in the scene.

Production designer Michael Riva notes that, “Allen and I scouted locations with an eye toward a certain quality of light. Steven wanted to shoot in the morning and at ‘magic hour’ outside, and go inside at the other times of day.”

In North Carolina, location manager Kokayi Ampah found a farm that had the light quality Daviau and Spielberg were looking for, as well as encompassing the geography for the environment Riva, Daviau, and Spielberg had agreed on in pre-production meetings. The farm, outside the town of Wadesboro, would be transformed into a 1920s farm, and aged, as Michael Riva points out, “to give the farm and the house a sense of character over the 30 year period of the movie.”

In terms of the quality of light the location presented, Daviau says, “I, quite frankly, not being experienced with shooting in North Carolina, had envisioned the light to be somewhat stark with a harsher quality to it since we were shooting in July and August.”

However, the light wasn’t always stark and harsh. The air was often moist and tended to soften the light. This was due to the higher than usual number of thunderstorms and overcast days in the region.

The major location secured, the $12 million production could now begin on the soundstage work, scheduled for three weeks on the Universal lot. In the meantime, Daviau had spent the days on the farm location going over with Riva what Spielberg had thought would be the most effective angles, how roads would run from one area to another, how buildings would tie one to the other. Now, Daviau would have to apply the same exacting attention to environmental details on the interiors built on the soundstage.

Daviau likes to get in early on the pre-production phase of the movie he is shooting and get involved in those details. “Something I’ve been able to do at Amblin Productions that I think should be done everywhere, is become involved at the very beginning of a movie; to have the week or 10 days, when the production designs are being formulated, when the locations are being scouted, when all these opinions are being given that will decide the look of the film.”

Daviau stresses that, “next to the director, my closest relationship on the film is with the production designer.” In terms of lighting and camera, he notes that the relationship with the production designer can give rise to suggestions of the designer “that will effect something vital in your thinking of the film.”

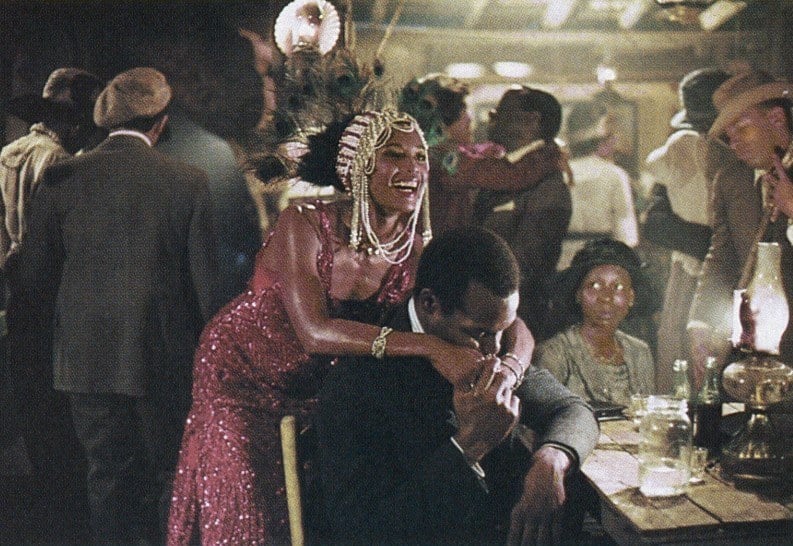

Riva’s “jook joint” set on the Universal soundstage was the most elaborate. He had built an authentic juke joint, a rural nightclub, of the early ’20s. In terms of lighting, and overall sense of the movie, the sequences shot on this set were very important. They would be the first scenes photographed on the schedule.

“I don’t think Michael Riva ever claimed it was going to be an easy set,” Daviau says of the “jook joint,” which was one of the many sets on the stage, including the farm house interiors.

Two scenes involving the juke joint were shot on the set, which was congested and humid, the humidity sometimes causing condensation to form on the lens. The major scene in the “jook joint” takes place at sunset, then fades into evening on a summer’s night. It is the scene of the character Shug Avery returning to sing, and every major character is in the scene.

“On the soundstage,” Daviau says, “the set was designed without windows. So half of the “jook joint” was a screened porch area. We had a lot of space, including slots in the roof boards to have beams of light coming in. So, we had the motivation of the setting sun pouring through one end of the juke joint, and the other end had no windows and was as dark as night time and lit only by oil lanterns.

“Knowing that these lanterns would supply the motivating sources in many areas, my gaffer, Norm Harris, had these lanterns ‘gimmicked’ to provide a certain amount of specific area lighting.”

“Bruton Peterson, one of his electricians, built some gadget lights — high intensity halogen globes — that would go on the back of the lanterns. We could gel for color and control their intensity with a dimmer. By placing these gadget lights outside the lanterns, we were able to keep a real kerosene flame burning inside the lanterns.”

When moving the camera, either on dolly tracks or with the steadicam rig, care had to be taken to avoid seeing the gadget lights in a shot. So, Coca-Cola and whiskey bottles were strategically placed to mask the gadget lights during these intricate camera moves that are a signature of Spielberg’s work.

Since the gadget lights were lighting specific areas, they didn’t cover all the lighting needs. So, advantage was taken of the the beams and rafters and support posts on the set. They became places to hide what Norm Harris calls “gator lights.” These are small, very lightweight, R-40 mushroom globe lamps, that can be fitted with gels and diffusion and controlled on dimmers.

Most of the lighting for the juke joint scene used the “gator lights” to “extend” the lanterns, though conventional lighting units were used, particularly to light the eye and create the sun shafts streaming through the rafters.

“Another factor limiting the use of ‘normal’ units in the ‘jook joint’,” Daviau says, “was the presence of a real ceiling that was often visible in shots where Shug Avery’s fans were sitting in the rafters, their dangling feet carrying the lens down to the frantic action on the stage and dance floor.” The addition of filtration — a mild Superfrost — “added to the scene a certain shimmer,” Daviau says, and created a palpable sense of the thickly humid atmosphere.

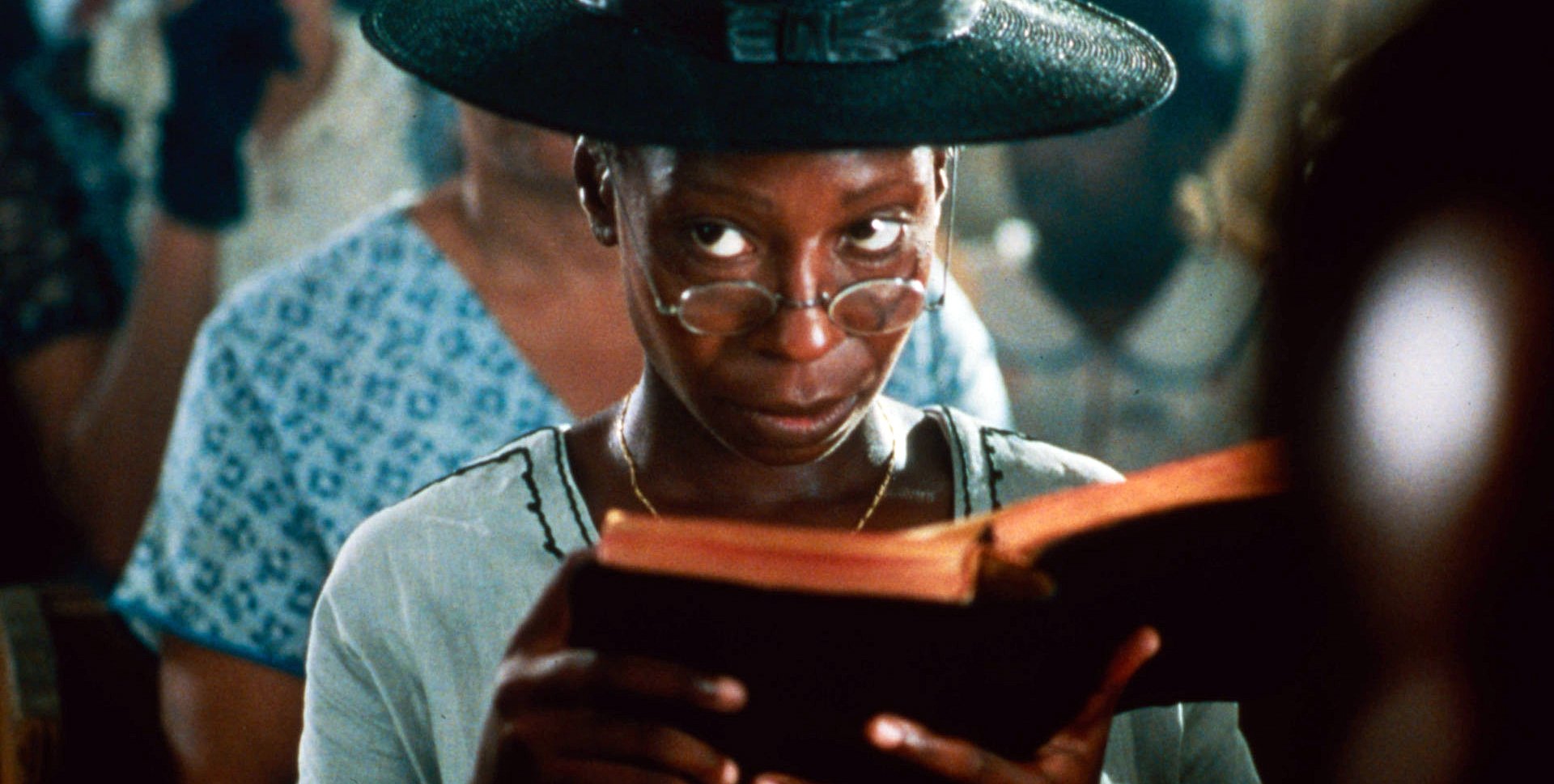

A cameraman often talks about the discovery of a lighting style that works for a person or place. Daviau uses the example of the Celie character, in this humid, frentic “jook joint” scene as an illustration of that discovery process.

“We have this tiny, scared woman, who has barely been off her farm in over a decade, yet there she is in a nightclub, a ‘jook joint,’ seeing a life she didn’t know existed, as a church going woman of that time,” Daviau says. “Here she was, almost hiding, in this marvelous old hat that Aggie Rogers, the costume designer got her, as all the action of the ‘jook joint’ happens around her.

“There was a quality to her, as she sat with her Coca-Cola, the kerosene lantern on the table beside her. We hid one of Norm Harris’ tiny gadget lights on the table, separate from the lantern, and I used this as her key light.

“This light worked so well for her. It was actually sitting on the table, so it motivates perfectly, in terms of direction; while it worked under the hat as a fairly sharp sculpting light.

“This shot is when we first realized the magic of Whoopi Goldberg’s eyes,” Daviau says, the emotions that this scene generated is readily recalled in his own. “It was one of those wonderful moments, when you’re working on a movie and you realize something special is really happening. You feel that you’ve just seen a character live on screen and you really know where the movie is going.

“Even though it might’ve been done for logistical reasons, it was a stroke of real genius by Steven to choose to start in the ‘jook joint.’ I think he knew in his heart that a lot of things would come together in this scene. It was one of those magic decisions that sets the tone for the film in all aspects.”

Within this scene, Daviau had run into some unique photographic problems that occur when shooting a film with basically an all-black cast.

“One of the things Michael Riva and I dealt with early on was having the set interiors and set decorations darker than normal,” Daviau says, his reasoning illustrating a seeming paradox when dealing with black faces on screen. “It is easier to deal with dark faces against a mid-tone or darker background than it is against a light background. The lighting on the faces can be much more subtle, and it is an awful lot easier to keep control of your walls, even when using large lighting sources.

“It is the face that you’re trying to keep in the foreground, so you don’t want clothes or walls or set decorations competing with the face.”

Both Riva and set decorator Linda DeScenna took this photographic consideration into the design and fabric of the sets and costumes, as did costume designer Aggie Rogers in her concepts. However, there were times when a period authenticity had to be maintained, so that neither set nor costume could be “teched down,” a term Daviau uses when mid-tones or dark colors and textures are used in set decoration and costuming in order to photographically complement the black movie actor.

According to Daviau, on The Color Purple, “Teching down, or subtly darkening certain scene elements by means other than lighting controls, was a very important area of cooperation with Michael Riva and all his departments. Normally, I pride myself on being able to handle a vast range of set, costume, and decor brightness. But when we were striving to keep black faces the primary point of focus for the audience, it was vital not to have the background elements compete with them. And, since Steven often wants complete masters of very mobile actors filmed with very wide angle lenses, traditional lighting control via flagging or scrimming is often just not possible. So, to twist John Alton’s phrase, we were forced to light with paint rather than paint with light.”

From this “teching down” consideration, Daviau was able to formulate some specific ideas about lighting dark faces. These ideas involved coordination with makeup artist Ken Chase, since not only did Chase have to deal with enhancing the actors’ normal look, but also with aging them over a 30-year period. “Ken likes a natural look and doesn’t like people overly ‘patted down.’ Particularly in The Color Purple we wanted the natural reflectivity of the skin to help the faces come out at you without overly lighting them,” Daviau says.

In commenting on how the aging make up worked for the photography, Daviau has special praise for Chase’s work. “To keep the skin from going dead by maintaining the reflectivity of their normal skin was quite a task.”

Skin reflectivity often determined how the actors were lit. Pigmentation and reflectivity don’t always go hand-in-hand. Often, though an actor may have been extremely dark, the actor was actually relatively easy to photograph because the natural oils in the skin reflected the light.

With the bulk of the interiors shot in the three weeks on the Universal sound stages, production moved to the North Carolina location for eight weeks.

Six weeks had passed since Daviau and Riva had walked around the farm discussing the look of the film. In that six-week period, greensman Danny Ondrejko had turned the farm into the landscape needed for the picture — fields of tobacco, pearl millet and sunflowers swayed in the summer breeze. Riva and his crew had built the “jook joint,” Harpo’s house, and had bought a church that had gone up for sale by its congregation, and transported it onto one of the open fields in view of the farm houses.

Daviau was using two cameras and two camera crews for the location work. The “A” camera crew, with operator Norm Langley, 1st assistant Todd Henry and 2nd assistant Joe Stanton, would be filming the primary scenes. The “B” crew, with operator Eric Engler, 1st assistant Reggie Newkirk, and 2nd assistant Bobby Samuels, would supplement the “A” camera, as well as stand by in a documentary-like readiness in order to photograph sudden changes in light and weather that could be cut into the film’s montage sequences that set up environment.

Both crews used Panaflex Golds with the rotating viewfinder, and Daviau used Kodak 5294 and 5247 for the exteriors, rating the 94 at ASA 250 for tungsten and ASA 200 for daylight. The 47 was rated at ASA 64. Both camera crews had to be extremely flexible because of the vagaries of scheduling and weather. Often as the “A” camera would be setting up for a scene and a sudden storm would arise, the “B” camera team would take advantage of the approaching storm and film it for a later sequence.

The first time we see the character Shug is a good example of how the two camera system worked. She arrives on the farm just as a storm is gathering in the distance. There is a montage of shots showing Celie on the porch waiting for Mister's return; a nervously quick series of shots of the animals reacting to the approaching storm, and shots of the darkening skies.

The sequence is a combination of footage. It is footage of the scene staged for the “A” camera and footage shot by both cameras, in that documentary-like way of catching the photographically interesting light or weather change, and in some cases shots of a darkening sky where grads were used to emphasize the storm quality of the sky. However, there are a number of shots that are genuinely afternoon thunderstorms.

“In fact,” Daviau says, “In the Shug arrival scene, where Celie is standing on the porch watching, we have real bolts of lighting. A bolt of lightning hit center frame. Steve said, at the time, that everyone is going to think ILM put in the lightning bolt.”

Regardless of weather or quality of light, there was still one other factor that was of major consideration on the location. It was a consideration that dictated the shooting schedule: the SAG regulations. “These may sound like boring things that shouldn’t have anything to do with photography, but often times they’re the really pertinent things that determine what time of the day a scene is shot,” Daviau says.

He adds, “Just because it was summer with longer hours of light, didn’t mean that certain guild restrictions were relaxed. If an actor worked into the evening, to take advantage of a beautiful sunset; it meant the actor couldn’t report to work until late the next day, unless the company pays for the expense of giving the actor a ‘forced call.’

“This means that the director and cinematographer are forced to choose between morning and evening ‘beauty’ light on a fairly consistent basis in order to keep the actors on a sensible schedule during the longer summer days.

“In the case of The Color Purple, the afternoon into evening phase on the farm proved to be most useful. Many of the scenes were planned around the low light in the fields and yards,” Daviau continues.

“Our editor, Michael Kahn, has certainly chosen, with an eye to continuity, from what actually was many different afternoons. However, all of us will be haunted by morning mists, ground fogs and sparkling, dewy mornings that were never filmed.”

This moist air quality, regardless of the angle of the sun, helped to soften the light. What Daviau calls “light fronts” were also useful. These fronts created a veil of light haze that added in the scenes of mid-winter in the movie, even though these scenes were filmed in August.

For the winter scenes, Riva and his crew defoliated the trees, as well as created snow. “We used little Epsom salts for the snow,” he says, “There was another material like flux, that was bio-degradable, that we used for the snow. Special blowers were rigged to blow the snow on the ground and in the streets of the town location.”

Besides snow, Riva also imported tons of red clay-like earth and spread it out on the streets to create the Georgia red clay. This red clay colored the way scenes were played, because it reflected back on the actors, highlighting their skin tones and separating them from the background.

For the location scenes in town, Daviau subscribed to the “world of two suns theory.” This theory of lighting allows the cinematographer and the audience visual continuity for scenes that start shooting in morning light and finish at sunset as the light is running out. This theory permits the cameraman to shoot in backlight as much as possible, because, “it gives smoother continuity for the audience, than going from back light to front light,” according to Daviau.

How to use light and the kind of light to use, in order to help shape a scene, was constantly examined in telling the story of the characters, as was creating a sense of inhabited environment for the characters.

“Steven Spielberg is always concerned about the audience understanding the geography — whether it be this entire farm or what’s happening inside a single room. He never wants anybody to be confused as to where they are,” Daviau says. “Early on he likes to tie together things; thus he has shots designed to show how places relate to each other.

“This genuine sense of environment and your orientation in this environment is established very early, so that as the story progresses and the editing style becomes more elliptical, with montage-like transitions occurring between and during scenes, you can’t be confused as to where you are.”

This sense of place had to be acute, because the camera was constantly moving about and exploring both the environment and the characters. The environment, in effect, is as much of a character as the actors. According to Riva, “The house had to undergo 30 years of history; and specific care was given to make the house have a sense of character.”

Because of the extensive camera movement, key grip Gene Kearney and dolly grip Don Hartley had to be ready to track hundreds of feet on short notice. Kearney, who has worked on a lot of films, says The Color Purple is probably a record holder for the number of feet tracked combining dolly and crane moves.

Even though Daviau was especially conscious of his lighting within the framework of the constantly prowling and examining dolly and crane moves, he admits that, “when you’re dealing with real exterior light, you’re going to have to rely on your timing in the laboratory.”

As far as the use of coral filters for color correction, he says,”I prefer to add color in the lab, working on the theory that it is easier to warm up an image than to cool it off.” Though Daviau did use an 85 filter, again his rationale is based solely on what occurs in the timing. “I like the positioning on the printing light scale that the 85 gives me.”

This strict consideration of what the lab work on a film contributes underscores Daviau’s position that, “When a cinematographer is working 3,000 miles from the lab and won’t see the dailies for one or two days, the telephone communication between the cinematographer and the lab is absolutely vital. In this case, the lab was Deluxe, and Michael Crane or Terry Claborn were available to assure me all was well or to alert me if there was a problem.

“The Color Purple was a picture free of techno-terrors, as we unfondly call them. Also, Jim Schurmann, the color timer of the final prints, was able to stop in on dailies occasionally and his input was always valuable.”

“I tend to agree with something Ansel Adams said: ‘The negative is the score and the print is the performance,’” Daviau points out.

Achieving that performance — particularly under the unusual circumstances of creating the score, with Spielberg eschewing the use of storyboards and allowing the acting to shape a scene, the constraints of time and weather, the fact that no one considers this translation a commercial venture of the scope of previous Spielberg films, and the very act of translating what is essentially prose poetry into visual poetry — would be a major photographic accomplishment.

But then Daviau and Spielberg are fully aware of the capabilities of that single instrument — light —and what it contributes to the score. And regardless of how the film performs, critically or commercially, it is a ground breaking film for a number of reasons. Allen Daviau’s work in the film’s translation of the literate into the cinematic has to be considered one of those reasons.

The cinematographer earned an Academy Award nomination for his expert camerawork, with the film earning nine others, including Best Picture.

Daviau was later invited to become a member of the ASC and honored with the Society's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.