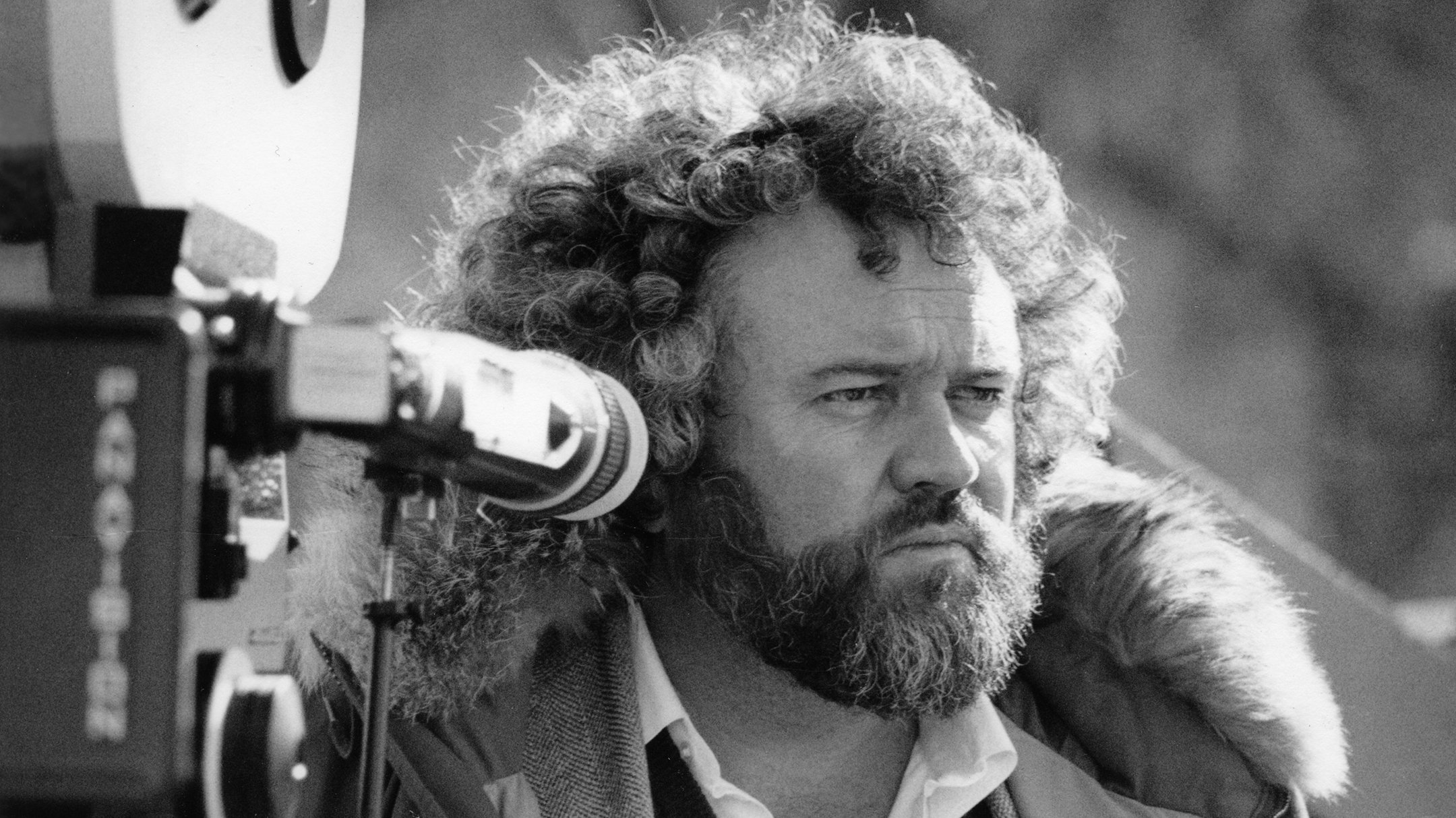

In Memoriam: Allen Daviau, ASC (1942-2020)

The exceptional cinematographer left behind an inspirational artistic legacy with such films as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, The Color Purple, Empire of the Sun, Avalon and Bugsy.

Esteemed ASC member Allen Daviau died on April 15, 2020 at the age of 77.

A longtime resident of the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital, he suffered from complications of the coronavirus. In his memory, we hereby re-publish this career-spanning profile from 2007, when he was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award.

We’ll publish a special remembrance piece on Daviau in the next available issue of American Cinematographer.

A Movie Buff’s Moment: Allen Daviau, ASC

One of cinematography’s most enthusiastic and accomplished ambassadors reflects on his career after earning the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award.

By David E. Williams

“I remember the first time I ever heard about the American Society of Cinematographers,” Allen Daviau, ASC said recently, addressing peers and friends at the Society’s Hollywood headquarters. He recalled a childhood of ardent moviegoing, during which he at one point noted the initials “ASC” after a particular cinematographer’s screen credit. At his mother’s suggestion, he did some detective work and called the Motion Picture Academy, which referred him to the ASC. He found a few answers that day, but his interest in cinematography was just beginning.

In the five decades since, Daviau has built an inspiring career, photographing such features as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Twilight Zone: The Movie, The Falcon and the Snowman, The Color Purple, Empire of the Sun, Avalon, Bugsy, Fearless and Van Helsing. Among other honors, Daviau has earned five Academy Award nominations and two ASC Awards. In recognition of his expertise in establishing period and mood, he has also been honored with the Art Directors Guild’s Distinguished Career Award.

Next month, the cinematographer will receive the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award. “I’m certain that some of Allen’s most important work is still ahead of him, but he has already made an indelible impression on the art of filmmaking,” says ASC President Daryn Okada. “His determination to pursue a seemingly impossible dream is a source of inspiration for filmmakers everywhere in the world.”

Born in New Orleans on June 14, 1942, Daviau was raised in the Los Angeles area. “Seeing color television for the first time at age 12 started my fascination with the technology of light and photography,” Daviau recently told an interviewer, noting that he was later employed at camera stores and film labs, where he gained experience and information. “These studies were enriched by meeting a remarkable guy named Bob Epstein, who was attending the University of Southern California Cinema Department during the late Fifties and early Sixties. He introduced us to De Sica, Fellini, Bergman, Bresson, Ozu and Kurosawa, and I soon realized what a phenomenal international artform this marvelous technology could deliver.

‘‘At about the same time, I was gate-crashing the set of One-Eyed Jacks, which Marlon Brando was directing and Charles B. Lang [ASC] was shooting. Lang was lighting this enormous interior, shooting Vista Vision on what was probably 50-ASA color negative. He seemed to be everywhere at once, fine-tuning the frame with the operator, adjusting the positions of the background players, tweaking the light from dozens of Babies. As he led a beautiful actress to her mark and subtly adjusted the shadow on her forehead, I thought to myself, ‘This man has the very best job in the history of the world.’” Daviau was hooked.

“Sometimes things get done because you’re too dumb to know they can’t be done.”

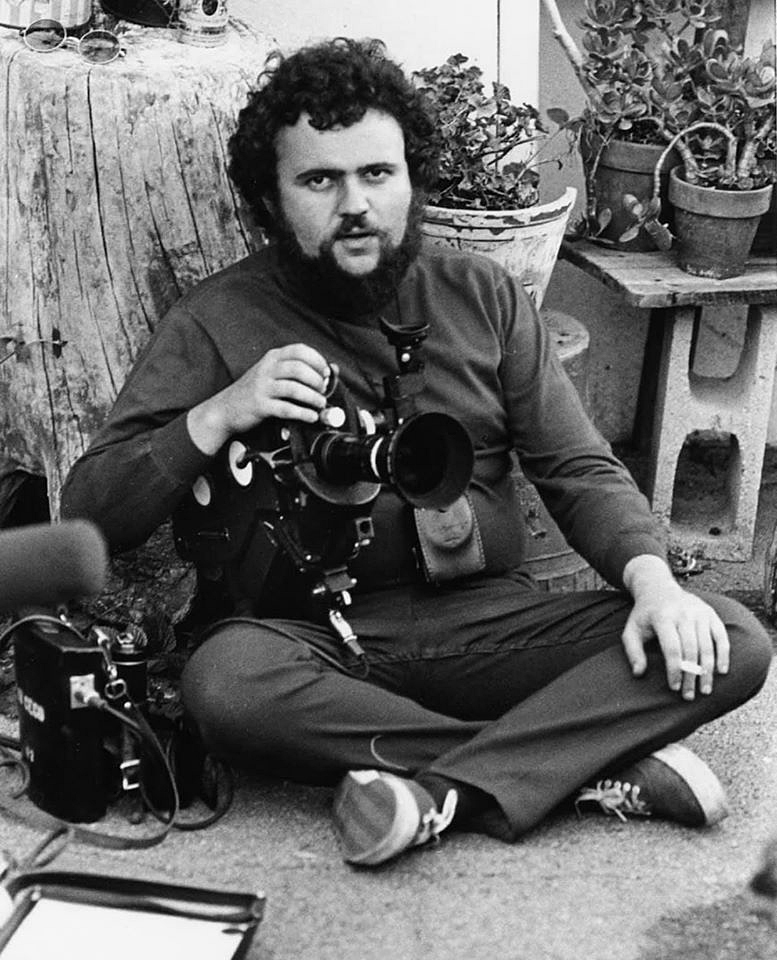

After graduating from high school in 1960, Daviau bought a 16mm Beaulieu R16E camera and three Angenieux prime lenses. He started shooting student projects, a music series for local station KHJTV, and proto-music videos for acts such as The Who, The Animals and Jimi Hendrix. He also worked as a still photographer on the TV series The Monkees.

“Sometimes things get done because you’re too dumb to know they can’t be done,” he later told American Cinematographer, describing how his unusual images gained him work shooting national commercials. “Commercials are the mainstay of keeping busy. You always have good equipment and crews, plenty of location work, lots of real interiors as well as studio sets, and an ever-changing variety of subject matter.”

In 1967, Daviau was introduced to young filmmaker Steven Spielberg, with whom he collaborated on the short film Amblin’. “Steven had seen some of my 16mm work,” he recalls. “He and I shared a great love of movies and tried to show that in this little film.”

Spielberg later told AC: “I wanted to break into the film business, and my 8mm and 16mm films weren’t doing the trick. When I was about 18, I’d worked with Allen on a short film that was never finished called Slipstream; it was shot by Serge Haignere, but Allen operated the B camera, and Allen and I became good friends. Amblin’ was a pretty big break for both of us. I don’t know how crazy we are today about our individual work in that film, but I always think of Allen as a terrifically versatile cinematographer.”

“[Before E.T.] I shot thousands of commercials, as well as documentaries, industrials and educationals — anything to keep myself working and expanding my knowledge of film. It was very difficult.”

Like many of his peers at the time, Daviau was not allowed entrance into the camera guild for many years and had to seek credits on non-union productions. As he explained to one interviewer, ‘‘After Amblin’, Steven tried to bring me along with him, and Universal even tried to sign me some sort of deal, but the union said, ‘Forget it.’ Back then, the union was nepotistic, and if you didn’t have a close personal contact [in the guild], you just did not get in. It took Andy Davis, me, and a handful of other cinematographers, including [later ASC members] Caleb Deschanel and Tak Fujimoto, a decade to gain entrance into the International Photographers Guild, and we finally had to file suit to do it. But, before that, I shot thousands of commercials, as well as documentaries, industrials and educationals — anything to keep myself working and expanding my knowledge of film. It was very difficult.”

This era included serving as a creator of psychedelic special-effects lighting on Roger Corman’s The Trip, and photographing the comedy Mooch Goes to Hollywood, the Oscar-nominated environment documentary Say Goodbyeand the absurdist feature Everything You Know Is Wrong.

After finally earning his IATSE designation, Daviau landed his first union job on the telefilm The Boy Who Drank Too Much. “[Director] Jerry Freedman gave me my first break with that project. It was filmed on a 19-day schedule and I tried for as much of a theatrical quality as possible. I think any cinematographer should try to do that if he’s lucky enough to work with production people who will let him go after as dramatic a look as possible. When time and money are limited, it’s best to concentrate your best efforts on the scenes that will do the most good and do the rest more simply.”

Daviau used the same approach on his next two telefilms, The Streets of L.A. and Rage! Soon, his tactics paid off in a big way. Shortly after shooting the feature Harry Tracy, Desperado, directed by Billy Graham, he received a momentous phone call. “Someone from Spielberg’s office called my agent to get another cameraman’s reel, and my agent asked them to look at my work as well,” recalls Daviau. “[Producer] Kathleen Kennedy said, ‘Sure, we’d love to: Well, I was doing a lawnmower commercial in Arizona at the time, and my agent immediately called me up to see what I could show Steven. Harry Tracy was still in post, so I decided to send him The Boy Who Drank Too Much; it had a lot of mood, and it’s about kids, so I knew Steven would watch it!” But, at the time, no print or tape of the film was available in Los Angeles, so an air print was sprung from the CBS vault, mounted on reels and delivered to the director.

That night, “I did something I rarely do,” Spielberg later told AC. “I didn’t think twice; I picked up the phone and asked Allen if he would photograph my next feature.”

Daviau recalls, “Steven said, I’m on reel three and this is exactly how I want my next movie to look: The next day I read the script for E.T. I had no idea how it was going to be done, but it was the greatest opportunity anyone could ever wish for.”

“I was an unknown person before E.T., so I know how fortunate I am as a result of that film.”

Seen through the eyes of a shy young boy, E.T. (cinematography story here and directing story here) details the youth’s befriending of a wayward alien stranded on Earth. This character-inspired perspective proved to be an overriding creative inspiration, with Daviau’s camera usually mounted low on a dolly. When the boy looks up at his older brother or mother, the camera also sees the upper walls and ceilings. Other shots represent E.T.’s perspective, an eye level that was not quite 3' off the floor.

Another distinctive aspect of the film is Daviau’s expert use of smoke effects, which in essence allowed him to “light air” using a practical-heavy approach in which sources were generally left in plain view. This technique was perhaps most expressively employed during the film’s extensive forest “exteriors,” some of which were shot on stages in Culver City that were originally built in 1917. The sense of history was not lost on Daviau, who noted, “I enjoyed working on the lot where King Kong and Gone With the Wind were filmed. There is a presence to a studio where great films have been made, and production designer Jim Bissell made the most of it.”

To maintain a sense of mystery and wonder, Spielberg didn’t want audiences to see E.T.’s face until late in the first act. “That probably gave Allen his biggest challenge;’ the director said later. “We’d see E.T. in silhouette, we’d see him in backlight, but we’d never get a good look at his face until later in the movie. It took many, many small lighting units, and because E.T. was very limited in terms of [range of] movement, it took a lot more time to light him than it did to light any of the humans. Allen spent hours giving E.T. more expressions than perhaps [mechanical creature-effects creator] Carlo Rambaldi and I ever envisioned, because he found by moving a light, by moving the source of the key from half-light to toplight, E.T.’s 40 possible expressions were suddenly 80. [It was all in] the way Allen shifted his light.”

“In describing what he wants in a shot, Steven will sometimes say two things that may appear contradictory,” Daviau told AC. “That means he wants you to work toward incorporating both. For example, he’d say, ‘I don’t want to see E.T.’s face, but I want to see him just enough.’ Challenges like that make for distinctive photography. For a scene in the bedroom where Elliot entices E.T. out of the closet, I had to make E.T. as near a silhouette as possible and still show his eyes!”

A runaway success that long dominated box-office charts, E.T. was a breakthrough for Daviau on all levels, instantly elevating him from relative obscurity and earning him Academy and BAFTA nominations. “I was an unknown person before E.T., so I know how fortunate I am as a result of that film,” he says.

He revisited the picture for its 20th anniversary theatrical re-release in 2002, and found the original negative and accompanying archival interpositive in pristine condition at Universal. “The experience was a testament to the archival quality of motion-picture film,” he notes.

After collaborating with Spielberg again on the Twilight Zone: The Movie fantasy segment “Kick the Can” and director George Miller’s rip- roaring horror entry “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” Daviau stepped into reality-based drama with the Cold War thriller The Falcon and the Snowman.

Daviau became a member of the ASC on July 1, 1985, after being proposed for membership by members Stephen H. Burum, Caleb Deschanel and Howard Schwartz.

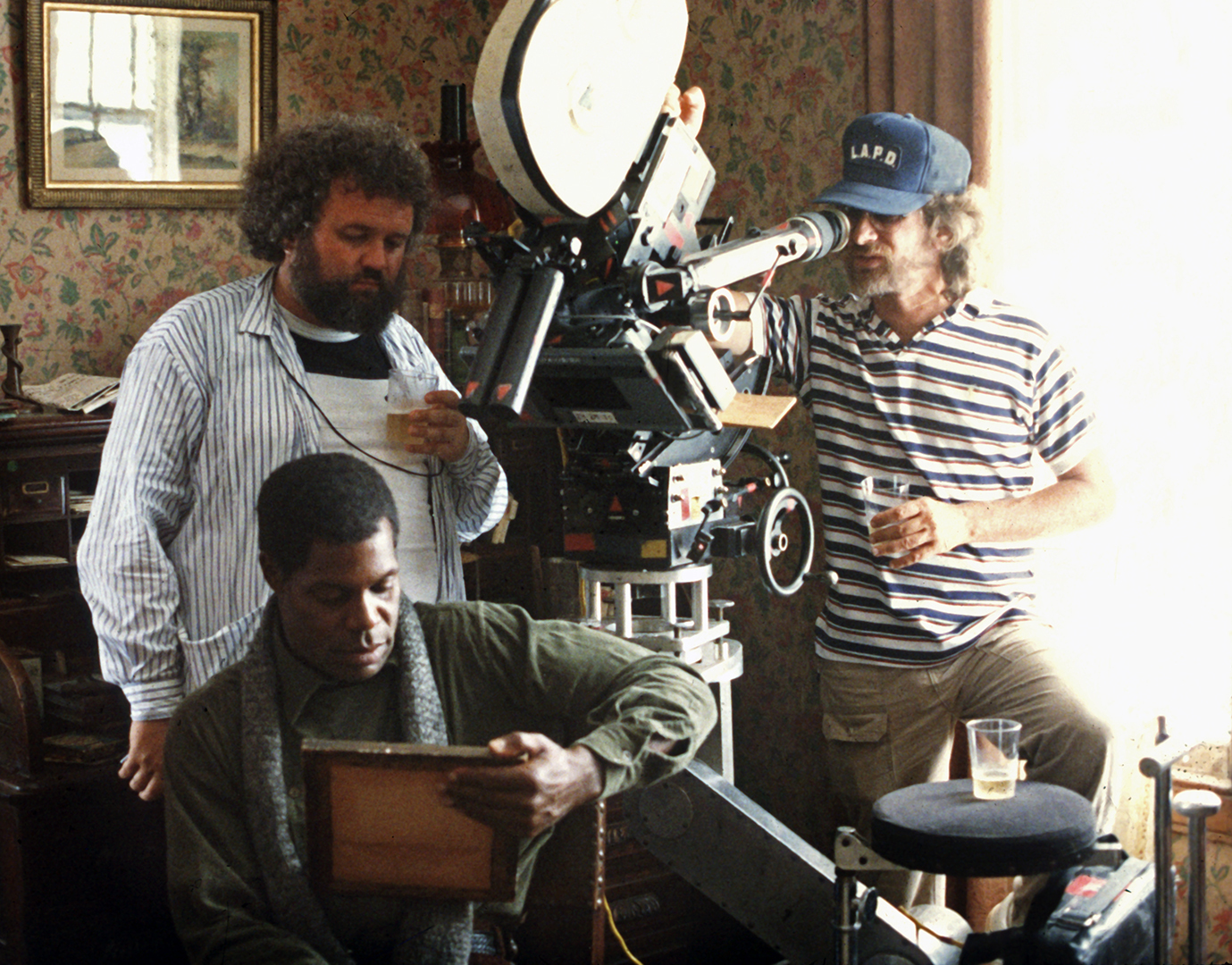

After re-teaming with Spielberg on an episode of the series Amazing Stories (“Ghost Train”) and shooting second unit on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the duo tackled a high-profile project that would endure heavy scrutiny throughout its production, The Color Purple (AC Feb. ’86). “When you make a movie from a Pulitzer Prize-winning book that has been widely read and greatly appreciated, everyone is just waiting to see what you will do with it,” Daviau told AC. “And it was an enormous story to tell. The photography had to serve the clarity of the storytelling first, and also delineate these characters you’re going to live with for over 30 years.”

“I tend to agree with something Ansel Adams said: ‘The negative is the score and the print is the performance.”’

Alice Walker’s tale is told in the form of “letters to God” written by a naive, long-suffering African-American woman (played by Whoopi Goldberg), and the film maintains this very human viewpoint throughout.

On location m North Carolina, Daviau, production designer Michael Riva and Spielberg analyzed every angle of their practical locations, nearby roads and adjacent buildings; the same attention to detail went into the interiors built onstage back in Los Angeles, including a rural “juke joint.” Daviau recalls, “Half the juke joint was a screened-porch area. We had a lot of space, and there were slots in the roof to allow beams of light to come in. So we had the motivation of the setting sun pouring through one end of the place, while the other was dark as night and lit only by oil lanterns.”

Because the lanterns had to serve as practicals, gaffer Norm Harris “gimmicked” the prop fixtures. His electrician built gadget lights — dimmer-controlled, high-intensity halogen globes — that would fit onto the back of them opposite the camera, allowing the lamps to burn with a visible real flame inside.

In order to fully read the expressions of the all-black cast, the filmmakers decided that “set interiors and set decorations should all be darker than normal;’ says Daviau. “It’s easier to deal with dark faces against a midtone or darker background than it is against a light background The lighting of the faces can be much more subtle and naturalistic. It’s the face that you’re trying to keep in the foreground, so you don’t want the [walls] competing with the face.”

Daviau’s use of a mild Superfrost-type filter in the juke joint “added a certain shimmer to those scenes,” he said, describing a palpable sense of humidity.

Because of the extensive camera movement Spielberg wanted, Daviau was especially conscious of his lighting, but “when you’re dealing with real exterior light, you’re going to have to rely on your timing in the lab. I did use an 85 filter, but I also prefer to add color in the lab, working on the theory that it is easier to warm up an image than cool it off. I tend to agree with something Ansel Adams said: ‘The negative is the score and the print is the performance.”’

For his work on The Color Purple, Daviau earned his second Oscar nomination.

“We had no dailies during our three-plus weeks in Shanghai. That’s one reason a cinematographer must learn to trust what he sees when he’s standing by the camera.”

In 1986, Daviau re-teamed with Spielberg on Empire of the Sun (AC Jan. ‘88), based on the autobiographical novel by J.G. Ballard. The story documents the experiences of a young English boy (Christian Bale) in occupied China during World War II, when he is separated from his parents during the Japanese invasion and sent to a POW camp. The production filmed in England, Spain and China, and Daviau found working in the latter country to be an exceptional lesson in logistics. “Getting people and equipment in and out of China took months of advance planning,” he said. “We understood in November [of 1986] that we wouldn’t be shooting until March [of 1987], but the decision of what equipment had to go to China had to be made right then, because equipment going by sea took three months to get around the world.”

Lab services posed another problem. The solution was to use an air shuttle that allowed Daviau to send everything to Technicolor London: “Each night, if we cut off at a certain point in the afternoon, we could make a flight from Shanghai to Hong Kong to London. That way, I could get a report on Monday’s footage by late Wednesday afternoon.” Unfortunately, this circuit did not work in the opposite direction. “We had no dailies during our three-plus weeks in Shanghai. That’s one reason a cinematographer must learn to trust what he sees when he’s standing by the camera.” Fortunately, Daviau also had the keen eyes of Technicolor’s Bob Crowdy and editor Michael Kahn to back him up.

Always on the lookout for helpful new filmmaking devices, Daviau relied on several throughout the shoot. Empire of the Sun was one of the first features to be shot using Panavision’s Primo lenses, which had just been delivered by the Leitz Co. of Canada.

For a soaring “God’s-eye” shot over the crowded streets of Shanghai, the modular Multicrane boom system was employed to give Daviau the reach he needed. A Haden stop changer, made in Sweden and adaptable to any lens, was used to quickly alter exposure in-shot when necessary. And, finally, Daviau took advantage of new high-speed daylight and tungsten film stocks from Kodak.

Although many viewers may best remember Empire’s spectacular action scenes, Daviau was drawn to the simple scenes that focused on the boy’s emotional trauma. “I think my favorite is when he returns to the European dormitory where he’d lived with an English couple. The woman [Miranda Richardson] allows him to come back, gives him back his bed and unpacks his possessions. He is so overcome by her unexpected tenderness that he breaks down and cries. It’s an amazing, effective scene.”

Empire earned Daviau his third Oscar nomination, as well as ASC and BAFTA trophies.

Daviau’s first feature for Barry Levinson, Avalon, chronicled the life and times of an immigrant family in America over six decades. “Avalon is Barry’s remembrance of the late Forties and early Fifties,” Daviau told AC in October 1990. “It’s an overall portrait of a family and the relationship of a young boy and his grandfather. The grandfather is always telling the children about what it was like when he came to America in 1914. He arrived in Baltimore during the Fourth of July [fireworks], and he had never seen so many lights. This flashback is used as the basis for the storytelling throughout; we have flashbacks to 1914, 1915, 1917, 1926 and 1939. The film’s present is 1948 to 1951, and at the end, there are some scenes in the Sixties.”

In visually establishing the period, the filmmakers decided to avoid using sepia-tone effects and heavy diffusion. “We had to find something new,’ said Daviau. One technique he used in flashbacks was to shoot at 16 fps and then use optical printing to “stretch” the footage to 24 fps in post. “We’ve all seen this in documentaries and presentations of silent films, but it makes a visual difference we’ve rarely seen in color. If everything in the shot is fairly stationary, it looks quite normal, but if something moves in the background, particularly across the frame, it certainly doesn’t look like 24 fps. It doesn’t have the hokey effect of speeded-up action, yet it is still somewhat distancing.”

Levinson likes using multiple cameras to capture performances, but Daviau does not, because he believes the lighting always suffers for it. “But this film really called for multiple cameras,” he noted, “because we had large-scale scenes of family gatherings with children, and we knew that if we shot the tight stuff on the children from the start, we’d get those initial reactions, which would otherwise be lost [doing multiple setups with a single camera]. In terms of matching, it helped in the coverage, but the lighting was certainly more difficult.”

Reflecting on the experience of making Avalon, which earned him ASC and Academy award nominations, Daviau noted the teamwork such a picture requires: “I think it was John Hora [ASC] who said that making a period movie is the closest thing we have to a time machine. It’s true; when you look through that lens, it should be like looking back in time. It’s many fine details that make the difference, and everybody who contributes has to be in tune. On that picture, I particularly enjoyed working once again with production designer Norman Reynolds, who had also been on Empire of the Sun.”

“Given the chance, all actors can do something amazing — you just have to watch for the moments, and they have to know you are watching.”

Daviau teamed with Levinson again on Bugsy (AC Nov. ’91), a stylish tale of love and deception depicting the life and death of mobster Ben “Bugsy” Siegel (Warren Beatty). Brutal yet suave, Siegel falls for the glamour of Hollywood, a beautiful actress (Annette Bening), and the dream of building a gambling oasis in the Nevada desert. For Daviau, re-creating the romance of Hollywood in the Forties was a dream come true. “I’ve been very lucky to make so many period films. Making any motion picture, but especially a period film, is about communicating with a lot of people. You have to be able to convince the actors that what you’re doing makes sense and is in support of their performances. It helps if you get to do some tests in prep, even if it’s just for hair, makeup and costumes. You need to talk to an actor about his or her concept of the character, and also ask, ‘Is there a film of yours that you thought had particularly good cinematography, in which you were effectively photographed?’ That will give you a great starting point for understanding how they see themselves. Annette Bening was such a joy in that way on Bugsy.”

Daviau recently revisited the picture for a new DVD release, and he notes that Levinson decided to include 12 minutes of previously excised scenes, including a favorite of Daviau’s in which Bening brandishes a .45 pistol. “She’s screaming at [Siegel] and punctuating each angry point by firing the gun at him, with things blowing up all over the set,” he recalls with a laugh. “She’s so gorgeous and fun, but you absolutely don’t want to mess with her. Given the chance, all actors can do something amazing — you just have to watch for the moments, and they have to know you are watching.”

For his work on Bugsy, Daviau earned his fifth Oscar nomination and second ASC Award.

“In the end, it all came down to helping Peter [Weir] tell a very intense and emotional story. I think it will leave the audience limp.”

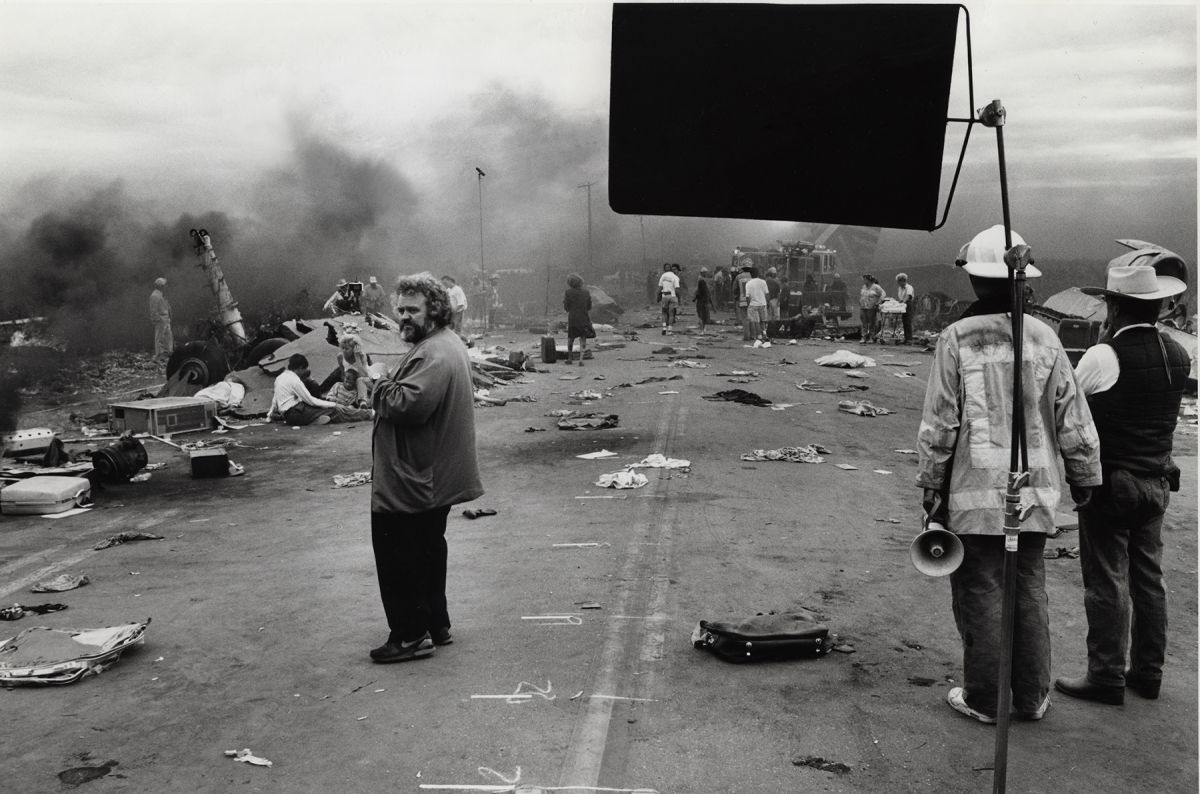

The cinematographer’s next feature, Peter Weir’s 1993 drama Fearless (AC Nov. ‘93), remains one of his favorites. A life-affirming meditation on fate, the picture literally opens with a bang as an unscathed survivor of a horrific plane crash, Max (Jeff Bridges), walks away from the scene, transformed by the near-death experience.

Some of the picture’s most gripping sequences are flashbacks set aboard the doomed flight, filmed on a full-scale aircraft set built on a gimbaled rig high above the stage floor. “Purist that I am,” Daviau details, “I wanted virtually all the light to come from outside, through the small windows. Banks of ninelights above, below and straight into the windows gave us that realistic source and the moody, contrasty look. Also, subtle use of streams of liquid nitrogen propelled past the windows by air movers mottled the light source, adding to the feeling of movement.”

Combining Paul Babin’s handheld operating with a series of techniques to suggest a spinning, chaotic world outside the stationary set — ranging from simple painted backings to the Introvision frontprojection process — Daviau brought a palpable sense of chaos to these scenes. “I now understand why Peter’s films have such incredible energy,” the cinematographer enthused to AC. “He distills the essence of the story. He creates a very open atmosphere where everyone is enthused about participating. In the end, it all came down to helping Peter tell a very intense and emotional story. I think it will leave the audience limp.”

During the 1990s, Daviau also shot the features Congo and The Astronaut’s Wife; hundreds of high-end commercials; and some experimental short films, including Sweet and The Routine. Over that span, he also served on the ASC Membership Committee, for which he sought out new talents that could help shepherd the Society into the next millennium.

In 2003, Daviau was lured back to feature-film work by the prospect of reviving Universal’s iconic monsters for the high-energy adventure Van Helsing (AC May ‘04). Taking a few visual cues from the studio’s classics — including The Bride of Frankenstein, photographed by John J. Mescall, ASC in 1935 — Daviau brought his period approach to the realm of Gothic horror, employing not only vintage techniques (such as hand-painted sky backings) but also the latest technology to bring director Stephen Sommers’ vision to the screen.

Reflecting on his latest ASC honor, which he will accept at the ASC Awards ceremony on Feb. 18, Daviau laughs and proclaims, “Know that this in is no way an announcement of my retirement! I’m not done yet!”

This extensive two-part interview with Daviau was conducted in 1992: