The Dramatic Photography of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Inspired camerawork is all-of-a-piece with brilliantly cinematic filmization of famous stage drama.

Perhaps once during each decade there is produced in Hollywood a film of such consistent excellence in every aspect of production that the entire American film industry, by association, is bathed in the radiant glow of its reflected glory. Such a motion picture is the Warner Bros. filmnization of Edward Albee’s jolting stage drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

If it is indeed the “masterpiece” which the nation’s top critics have almost unanimously proclaimed it to be, its true greatness lies not merely in its stunning impact upon audiences, but even more importantly in the fact that it represents the blending of a multitude of diverse and highly individualistic talents into a superbly integrated artistic entity.

It would be impossible to single out any one element as being outstanding above the others, so beautifully do they merge in creating the total effect. The blood, sweat and probable tears of its many gifted craftsmen are evident in each frame — and though it may seem paradoxical to apply the term to so vicious a drama, the film is quite obviously a “labor of love” wrought by artisans who value excellence for the sake of excellence.

Producer-scenarist Ernest Lehman, with almost reverent respect for Albee’s crackling dialogue, has trimmed and shaped the fabric of the play, releasing it from the confines of the single stage set so that it becomes fluidly cinematic and definitely not a photographed stage play.

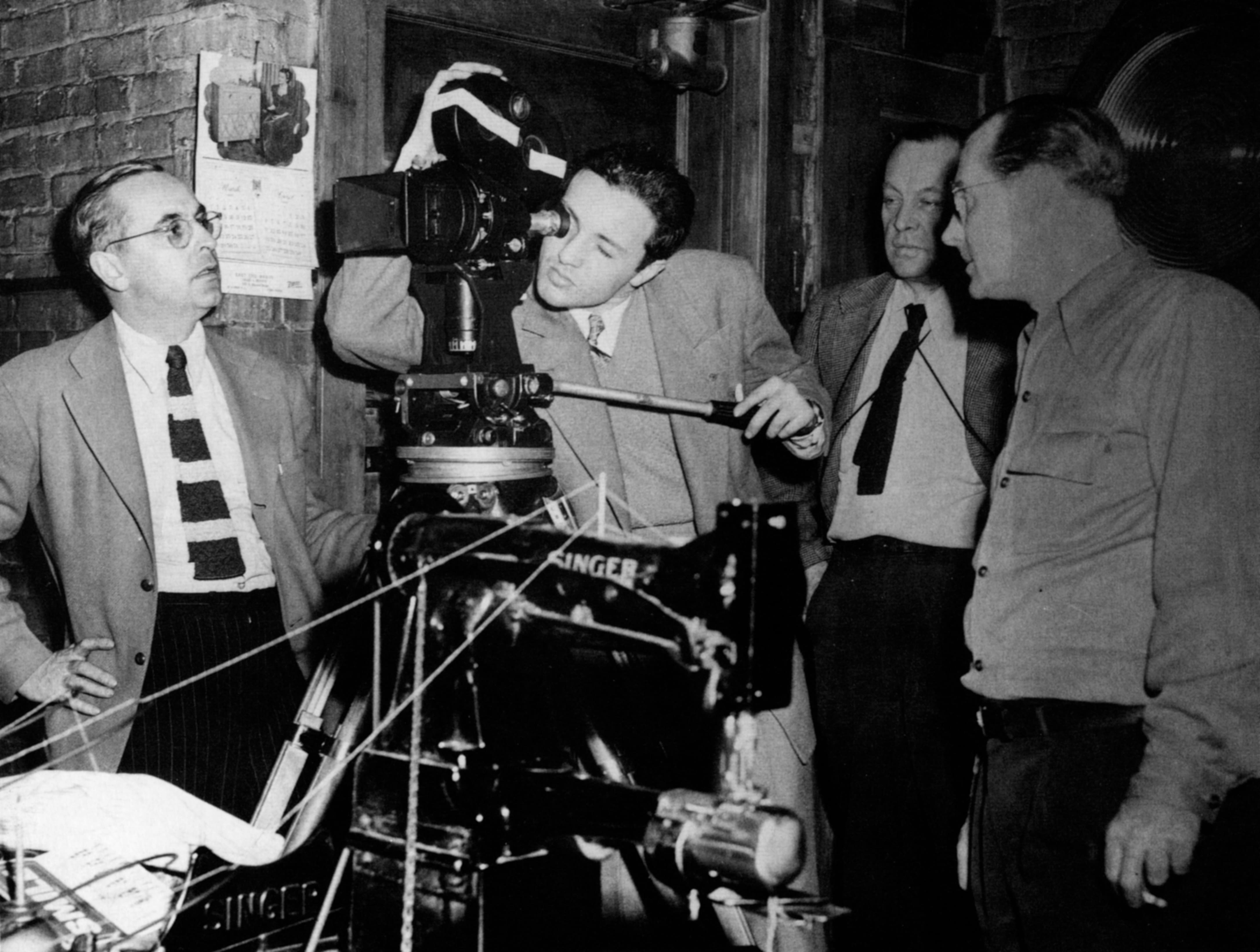

Director Mike Nichols, essaying his first sortie into the complex medium of film after having directed four consecutive smash comedy hits on the Broadway stage, draws from his actors' performances of such searing realism that they scarcely seem to be acting at all.

Selected for the important task of capturing the volatile drama on film in terms of light and shadow was director of photography Haskell Wexler — and it was, by his own admission, a rather odd assignment. Wexler’s forte is the documentary film and its second cousin, cinéma vérité. He especially enjoys filming in actual locations, photographing by available light and working with actors who are usually not actors at all. His major screen credits include the photography of Elia Kazan’s America, America, and Tony Richardson’s The Loved One, but both of these pictures were filmed almost entirely on location in semi-documentary style with no big-name actors.

Virginia Woolf was something else again. Despite five weeks of location filming in Northampton, Mass., it is essentially a “studio” picture made on a sound stage. Except for rear-projection process plates shot at night, there is no available-light photography in the film. On the contrary, the vigorous staging of action in confined sets demanded the most precise sort of controlled lighting. Lastly, the personalities appearing before the camera are not derelicts recruited from Skid Row because they look the part. The highly professional cast includes two of the film industry’s most important international box office stars.

All of these elements, which are taken readily in stride by studio-oriented cinematographers, added up to a sizable challenge for Wexler. To say that he rose to that challenge superbly is not saying enough. His gutsy, graphic, audaciously bold, richly inventive, fluid style of cinematography is exactly right for Virginia Woolf and it is one of the elements most directly responsible for the film’s powerful impact upon the audience.

“The suprising thing about Mike Nichols is that every day during shooting he learned more about filmmaking than the average person would learn in years, because he has a fantastic mind and is an ‘addicted’ filmgoer.”

— Haskell Wexler

Wexler himself tends to minimize his contribution to the production. “Many people know that this is the first picture which Mike Nichols directed and they assume, since that is true and because I have had some experience in the medium, that I contributed perhaps more than I actually did to the end result of the film,” he states, with no suspicion of false modesty. “But the suprising thing about Mike Nichols is that every day during shooting he learned more about filmmaking than the average person would learn in years, because he has a fantastic mind and is an ‘addicted’ filmgoer. He has seen all of the best films, has appreciated them and digested them — and because of this it wasn’t nearly so complicated for him to switch from stage direction to film direction. I did try to help him, wherever possible, to apply the mechanics of cinematography to gaining the effects he had in mind — because the film medium has its own special technology and some of the mechanics were unfamiliar to him.”

As a drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is basically a four-character study in psychological violence. It is the story of Martha and George, a self-destructive, embattled couple who live a corrosive married life on the campus of a New England college. Martha is an aging neurotic whose tumultuous frustrations drive her to extremes of vicious vulgarity. George, sharp of tongue and waspish of wit, suffers from a lost idealism, gnawing guilts of the past and the psychically emasculating attacks of his cuckolding wife.

Late one Saturday night they return home from a party to await the arrival of a “new” couple, Nick and Honey, whom Martha has invited over for drinks. Martha blatantly seduces the ruggedly good-looking Nick while his plain socially awkward wife looks on through a haze of alcohol and George sobs in impotent agony. It is a bruising orgy of fun-and-games that move viciously from “Humiliate the Host” to “Get the Guests.” It is a Walpurgis night of bared souls and misfired lust and spiritual cannibalism. The no-holds-barred flaying of facades mounts in fury until the dawn, when the exorcism is complete.

“Unlike plays, which must concern themselves with crucial moments, films hold a great deal that is not crucial — but it must be accurate. Movies are life-like, because you can’t cheat.”

— Mike Nichols

The photography of the picture had to reflect the harsh, clawing violence of the four alienated characters in conflict with themselves and with each other. The camera was required to become a fifth character in the melee, moving into the eye of the emotional hurricane to record the subtlest nuances of psychological interplay, for as Mike Nichols put it: “On the screen there is room for the complicated, mysterious, tenuous, small, subtle things... Films are made up of small moments — not great climatic scenes and confrontations. Unlike plays, which must concern themselves with crucial moments, films hold a great deal that is not crucial — but it must be accurate. Movies are life-like, because you can’t cheat.”

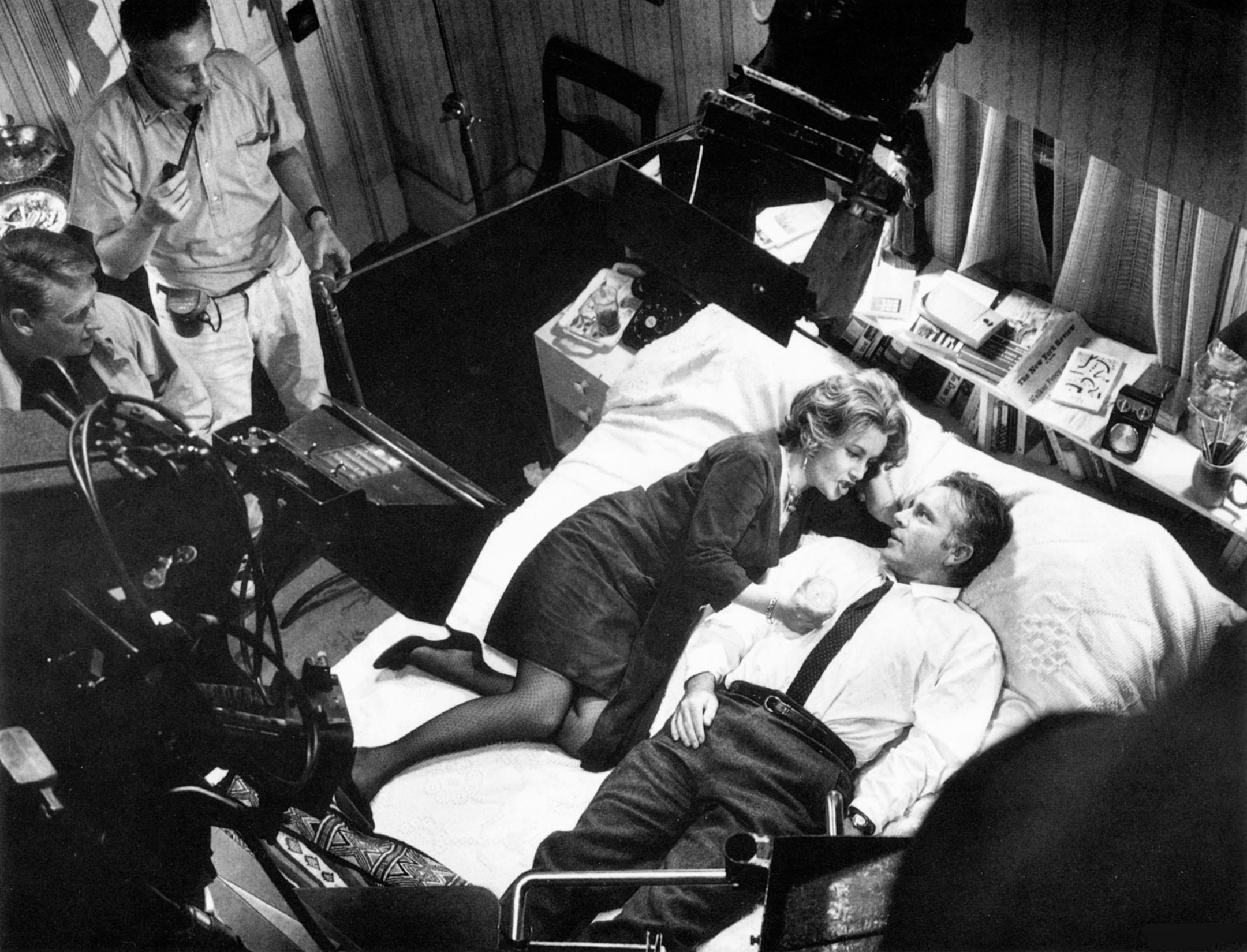

In order to gain a definite conception of the characters, their relationships to each other and to their environment, director of photography Wexler sat in on the last four days of the three-week pre-rehearsal period at the studio. As the actors spoke their lines and walked through blocked movement on the set, the characters began to assume form and substance, and from this the cinematographer took his cue as to how they should look when lit.

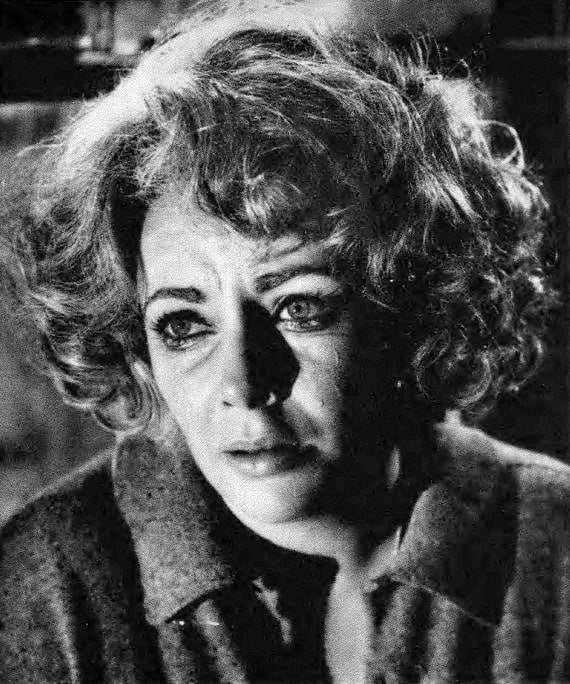

His first challenge was that of transforming the beauteous violet-eyed Elizabeth Taylor into the character called for in the script: a sloppy, fading voluptuary, her disheveled hair streaked with gray, her eyes pouchy and her face bearing the ravages of too much alcohol and too little sleep.

Makeup helped somewhat, as did a salt-and-pepper wig and weight purposely gained for the role. But, even so, the natural radiance of “the most beautiful woman in the world” was difficult to diffuse. Wexler studied the famous face for characteristics that could be exaggerated and distorted with light. He shot one day of tests substituting for the normal high-key “glamour” light a lower, flatter light which could get in under the chin area to create an illusion of roundness and flabbiness. It was only after he had pulled out all the stops with this “wrong” kind of lighting, that Nichols was satisfied that Martha looked “baggy” enough.

The next major photographic challenge was that of the magnificently realistic sets created by production designer Richard Sylbert, who visited 18 college campuses and faculty members’ homes to absorb their atmosphere so that he might design authentically the home of George and Martha and install the visible marks of their long residence there. Every book in the house was hand-picked, as were the trivia and knick-knacks, the magazines and paintings. It is a messy, cluttered house representative of the sloppy intellectual world in which George and Martha live and, as such, it helps immeasurably in telling the audience what these people are like.

From the photographic standpoint, however, the configuration of the main set was very confining. The dimensions were literally those of an actual house and the hallways were extremely narrow. Realism extended even to the use of warped boards in constructing the floor — an almost too-authentic touch which precluded the use of a crab dolly and made it necessary for tracks to be laid for all moving camera shots.

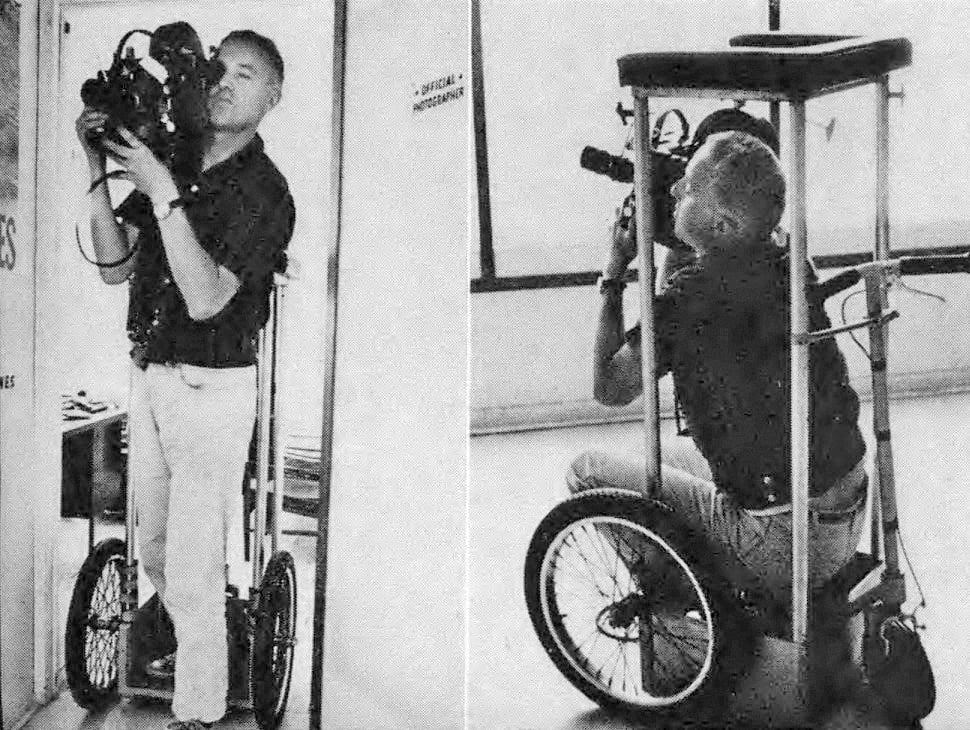

Because of his documentary background, Wexler was undismayed by these obstacles. They merely stimulated him to devise unorthodox methods for achieving the free fluidity of camera movement which he felt was necessary in order to follow the fast-paced action. The handheld camera equipped with a zoom lens became an important tool in this respect, as did an odd-looking camera cart — as yet unnamed — which he designed and had built for the purpose.

In filming his famous documentary The Bus — as well as a film on Igor Stravinsky made for CBS [Stravinsky (1966)] — Wexler had employed a wheelchair adapted as a dolly — a device often used by cameramen who have to shoot in cramped quarters. It worked well enough, but the camera angle was always the same — rather low, so that the lens continually seemed to be looking up at people.

In order to bypass this limitation, Wexler designed and had built by a friend who repairs helicopters a tall device somewhat like a wheelchair with two large bicycle wheels and a platform upon which the cameraman can stand or sit at any height. There is only a half-inch of clearance between the base of the platform and the floor, so that an operator with a handheld camera can step off of the platform, while continuing to shoot, and walk with the camera. In order to photograph several tricky scenes during the filming of Virginia Woolf, he did exactly that. Such a scene would begin with a dolly shot in which the camera operator would be pushed forward standing on the platform of the Rube Goldberg-type contraption. When the device had reached the limit of its mobility, the operator would continue the movement by stepping smoothly off of the platform and walking the camera.

The handheld camera employed was a 35mm Eclair equipped with a 24mm-to-240mm Angenieux zoom lens, and it was used extensively throughout the production to film scenes which Wexler felt would have been much more difficult and time consuming to photograph using bulkier, conventional studio equipment. He also appreciates the fact that the reflex characteristic permits the operator to view the action through the lens, thus eliminating problems of parallax.

The handheld camera was used dramatically for the scene in which Richard Burton, playing George, strides down a long narrow hallway to get a shotgun out of a cupboard. It was used in all of the “violence” scenes to follow the erratic movement of characters struggling with one another. It was used most effectively in one scene where Burton goes outside and finds the young wife, played by Sandy Dennis, asleep in the car. He then walks back to the house, up the stairs, onto the porch and begins pounding on the locked door. The camera operator follows him, walking with the hand-held camera. This method not only saved considerable time by eliminating the necessity of laying lengthy dolly tracks, but it permitted the cameraman to stay with the requisite violence at the end of the scene. In such a case, in order to minimize the inevitable slight bobbing movement as the operator walked with the camera, a relatively short focal length lens was used.

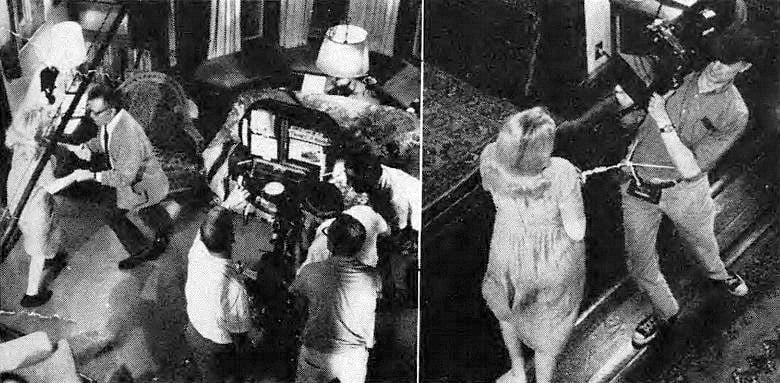

In one sequence, where Burton is shown whirling about the dance floor with the drunken Miss Dennis in his arms, the handheld camera is used subjectively to simulate his point of view. To film this shot, the operator holding the camera was actually roped to Miss Dennis in order to maintain a consistent distance from her as they whirled about.

It is to Wexler’s great credit that the handheld camera is so smoothly employed in Virginia Woolf and so skillfully synchronized to action that it is never obtrusive or distracting. There are none of the self-consciously arty pogo-stick camera convulsions affected by certain misguided nouvelle vague types — to the great annoyance of the viewer. There is no frenetic camera movement for its own sake. In fact, the average viewer would never be aware that a hand-held camera was being used.

“Whenever it is possible, the camera ought to be mounted on a tripod, because in making films, the filmmaker should never call attention to himself or the mechanics of his technique.”

— Haskell Wexler

“I’m of the opinion that whenever it is possible, the camera ought to be mounted on a tripod,” Wexler maintains, “because in making films, the filmmaker should never call attention to himself or the mechanics of his technique. The purpose of cinematography is to tell the story on film, and I only use the hand-held camera where I really feel that it will help to do that, or where it facilitates shooting of a particular scene.”

He manifested similar restraint in the use of the zoom less. In only one sequence (that in which George menaces his wife with a shotgun) does he make extreme use of the zoom. In that sequence shock value is achieved through a series of rapid zooms that fill the screen with the horrified reactions of the onlookers.

Otherwise, the use of the zoom is quite subtle. In one sequence where Miss Dennis (who is about to be sick) rushes down the hallway toward the camera, it is pressed into service as an effective substitute for a dolly. It would have been practically impossible to execute a fast pullback shot within the cramped confines of the narrow corridor. To solve the problem, Wexler simply widened the angle of the zoom lens as the actress rushed toward the camera, maintaining a relatively consistent image size, and, in effect, pulling back with her.

The particular lighting style used in Virginia Woolf — especially that of the living room set where most of the action takes place — actually involved a subtly changing progression from a definitely stark character at the beginning of the film to a soft, diffused quality at the end.

There were two reasons for this. One was dictated by the fact that the almost continuous action of the script begins late at night and continues until dawn. Progressive changes in the character of the light helped to denote physically this passage of time.

The second reason was based on a progression of psychological undercurrents running throughout the film and which, in concept, differed sharply from that of the play as staged on Broadway.

“The stage version of the play upset me greatly when I saw it because it seemed unrelenting and almost inhuman right up to the very end.”

— Haskell Wexler

“The stage version of the play upset me greatly when I saw it because it seemed unrelenting and almost inhuman right up to the very end,” Wexler explains. “The film version, as Mike Nichols directed it and the Burtons played it, seems instead to indicate that there is some human compassion, some spark of warmth between these people that goes beyond the horrible games they play. It seems to say that they were young and in love once in the normal way without the perverse hostility and that, in some strange way, they still have love. I felt that a gradual softening of the light would help to establish the idea that they had reached the beginning of the end of this mad game they were playing.”

In order to achieve mechanically the progression from harsh to soft lighting, Wexler started out by using “hard” light provided by baby spots with no diffusion before the lenses. As time passed and the action progressed, he began to place silks and spun-glass diffusion in front of the lamps. Finally, during filming of approximately the last fifth of the picture, he used a CoIorTran Soft-lite quartz-iodine unit as the key to provide a kind of “wall” of diffused illumination. Its source was established as that of ambient light filtering in through the windows as dawn broke.

“Quartz-iodine lamps seem to have the ability to sort of eat around to the other side of a subject even when the light is all on one side,” observes Wexler. “I believe the greatest advance in this type of light so far has been the design of units that provide a rather strong light source that is soft.”

Contrary to usual procedure, the action of “Virginia Woolf was filmed in continuity, with complex master scenes recording large segments of the action. More intimate shots and closeups were filmed later to be cut in to the master scenes. It would seem that by using this method of shooting, a general set illumination could be pre-set and left that way, but such was not the case. Wexler altered his lighting for each set-up to record the particular action pattern to best advantage. In order to create a subtle range of mood, the key-to-fill light ratio was varied from sequence to sequence, with more fill being used in those sequences where the action took a lighter turn. To accomplish this a cone light was mounted above the set and rigged to a dimmer.

Wexler prefers to shoot black-and-white film at an average level of 175 foot candles, but in Virginia Woolf, this level had to be raised whenever the zoom lens with its working aperture of T4 was used. The level had to be increased still more in order to achieve some of the dramatic “depth-of-field” shots requested by the director. In one such case, where there was an unusually wide split between a big head in the foreground and another player in the distance, Wexler shot the scene with a 32mm lens stopped down to T11. In the more extreme situations, rather than flooding the set with uncomfortable levels of light, he helped minimize the problem by switching from his normal Eastman Plus-X filming stock to Double-X, with no apparent difference in contrast or grain.

In the opening sequence of the film, George and Martha leave the house where they have been to a party and walk home across the almost totally dark campus. At the point where they enter their own house and switch on the light. Director Nichols said to Wexler: “I want it to look like when you first come into your house from the dark and the light hurts your eyes. I want it bright, bright, bright!" The director of photography had momentary qualms about following that particular suggestion. “My natural instincts fought against it,” he explains, “because I could just hear my fellow cinematographers saying: ‘Aw — the so-and-so overexposed it!’ But I took the cue from Mike because I thought it was a good cue. I did overexpose the scene a full stop so that when they come in from the dark and throw the switch, the light really blasts.”

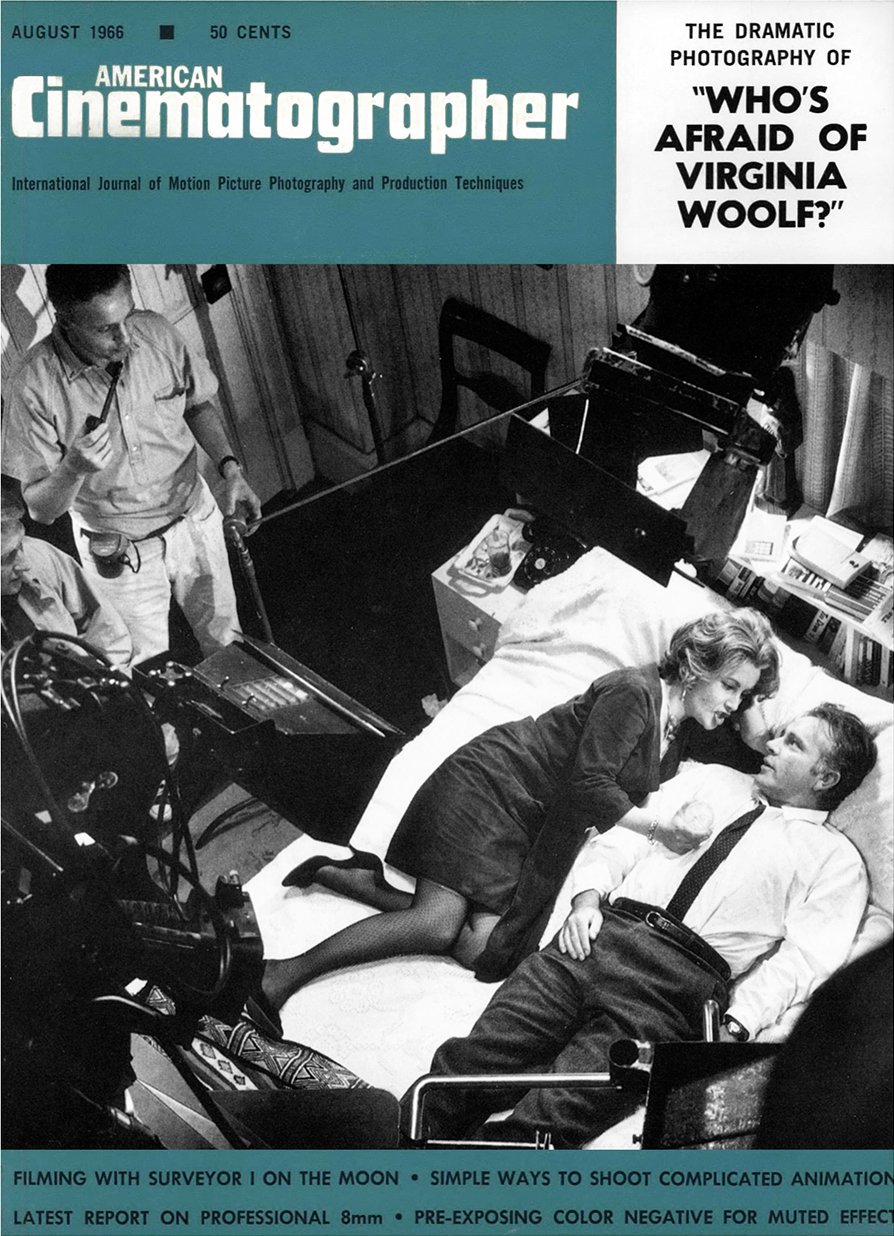

(next to camera) and Wexler (top left) study the action.

Although the lighting in the living room set, keyed to simulate sources from practical table lamps, is of a rather extreme key-to-fill light ratio, there are a few sequences which lent themselves naturally to rather flat lighting and incidentally provided a certain visual variety to the film. The sequence which takes place in the kitchen, for example, is just such a situation. The set was illuminated from the top with cone lights that produce no hard shadows, just as many actual kitchens are lighted. A slight concession was made to fill light from the floor so that the eyes of the players would not look like black holes, but no flags or cutters were used to gobo the light. The kitchen is presented in flat, drab light that accentuates the clutter and ties in well with Martha’s line: “What a dump!”

The five week location safari to Northampton, Mass, for the purpose of shooting exterior locations for Virginia Woolf turned out to be a kind of nightmare excursion made hideous by almost constant rain, throngs of curious spectators and on-again-off-again fog.

In the interest of realism, and following an extensive search for just the right sort of campus, arrangements were made with officials of Smith College for the exteriors to be shot on their grounds — with the rigid stipulation that the college was not to be identifiable in the finished film. So assiduously did the filmmakers respect this prohibition that the college is practically non-existent in the final cut. Only in a few night shots, mostly under titles, does the audience catch an occasional glimpse of one of the ivy-covered halls of learning. There is considerable feeling (now that hindsight is available) that these sequences might have been filmed more conveniently in some park-like glade not too far from Hollywood.

On location, Wexler had his hands full rushing to get footage exposed and in the can between rain storms. Another struggle involved trying to match “non-fog” footage with previously exposed “fog” footage by means of fog filters and special effect devices.

All of the location exteriors were shot night-for-night using the Double-X emulsion. The lighting equipment included a quantity of Garnelite units, (boosted by means of step-up transformers), several 5,000-watt lamps and two arc lights for long throws. One of the many challenges was finding ways to conceal the lamps in the vast reaches of the campus greensward. Another major problem arose from the fact that because of the extreme amount of moisture and haze in the atmosphere, the defined beams from backlights and crosslights were clearly visible.

In the famous parking lot sequence, Nichols and Wexler, both admirers of Fellini’s stylized autobiographical film, 8 ½, decided to use a similar camera approach to achieve a kind of "swimming quality." Wexler used a 100mm lens to follow the drunken characters, thereby fuzzing out lights and other objects that swam about in the background, creating the illusion of a real setting, but abstracting the characters from it. When Nichols decided that the “circus” quality of the sequence might be further enhanced by creating a starburst effect with the lights in the background, Wexler bought “a few fathoms” of common window screen at a hardware store and produced the effect simply by mounting a small piece of screen in front of the lens.

There is a lengthy sequence in the film that takes place inside a station wagon as the two couples drive to a roadhouse. The conventional way to shoot such a scene, of course, is with a cutaway body of the vehicle filmed against a process screen. Wexler felt, however, that the sequence would be more effective if it were shot with a hand-held camera inside an actual car as it moved through the town of Northampton.

As a test, before leaving for location, he coupled a 16mm Eclair camera for sync-sound with a Nagra recorder and drove down Hollywood Boulevard filming a dialogue sequence of two stand-ins carrying on a conversation in the back seat. The only illumination came from the exposed dome light plus whatever spill-light seeped in from the street lamps and neon signs along the way. Blown up to 35mm and projected, the test looked beautiful and it was decided to film the actual sequence in the same manner, but using a blimped 35mm Eclair instead of the 16mm unit.

In Northampton, accordingly, the interior of a “stretchout” limousine was rigged to simulate that of a station wagon. Outrigger platforms were also constructed on either side of the vehicle so that the camera could be operated from the outside to get 45-degree angle close-ups of the actors. The intention was to shoot the entire sequence in the moving vehicle on location. However, milling crowds of celebrity-seekers combined with the inclement weather to make this plan impossible and so it was finally decided — reluctantly — that the sequence would have to be filmed before a process screen in the studio.

Before a process screen in the studio. The fronts of actual buildings, including George and Martha’s residence and the roadhouse were filmed for establishing shots on location. Back at the studio, segments of these exteriors plus full interiors were constructed on the sound stage. The fact that the studio sets match so well to the location sets Wexler credits to the skill of production designer Sylbert. “The talents of a good art director are essential to the work of the cinematographer,” he observes. “It’s important to know him and his work and, if possible, to be assigned to the picture far enough in advance so that if something won’t work out photographically there will still be time to change it.”

To accomplish moving camera shots on location a crab dolly and Chapman boom were used. For one lengthy crane shot following the characters from the roadhouse to their car the problem of concealing the crane tracks was solved by covering them with cases from the Garnelite units.

Back at the studio, Wexler found that the “swimming effect” created by using the 100mm lens to follow action could be used to advantage for aiding actors to sustain large segments of action and dialogue while moving about the set in compositions ranging from closeup to medium shot. A man who dislikes over-the-shoulder shots while recognizing their dramatic necessity, he would also use the 100mm lens to shoot such compositions, deliberately fuzzing out the foreground figure so that his peripheral presence was sensed hut not clearly defined.

“What I like most about Elizabeth is that she is so considerate of everybody down to the supposedly least important member of the crew.”

— Haskell Wexler

Of the stars of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf cinematographer Wexler comments: “The Burtons are great to work with. They’re intelligent and completely professional. What I like most about Elizabeth is that she is so considerate of everybody down to the supposedly least important member of the crew. She’s a real trouper who goes right on working even when she is actually ill. She is really a very, very fine woman.”

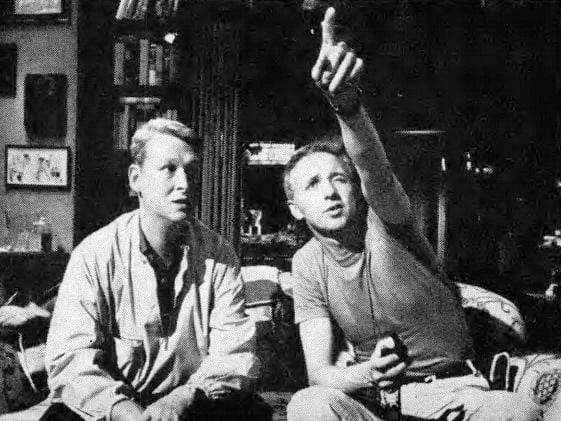

Wexler credits much of his satisfaction in working on Virginia Woolf to the fine rapport that existed between himself and Director Nichols.

“The director-cinematographer relationship is extremely critical. It’s important for these two working together to have a community of language and a mutual respect for each other,” says Wexler. “Mike Nichols is brilliant. I secretly think he’d like to be a camera operator — and he’d be a good one. We would view the dailies together and have many discussions about what we liked and what we didn’t. Some of my suggestions he accepted, others he didn’t. The director is the captain of the ship and he has the final say — “but it’s essential for the cinematographer not to get his feelings hurt to the point where he stops giving. The important thing is to care. A good director can bring the best out of a cameraman and I feel that cameramen have a responsibility to help the director do his best, too. There is no shot that is impossible and a cameraman should never say that a shot can’t be done. He should try to give the director the shot he wants— but he cannot be just a ‘yes-man.’ If he prostitutes his talents, he will begin not to like himself, and if he can’t do that, then nothing else matters. I have worked with other brilliant directors, like Elia Kazan and Tony Richardson. These men know what they want, but they are always experimenting. I believe the cinematographer should have the opportunity to experiment, also — because if he is ever going to discover more exciting ways to tell the story with film he has to take chances. It is to the advantage of studios and directors to encourage the cinematographer to take these chances. If they don’t, his work will be professional — true — but it can never be inspired.”

Wexler earned an Academy Award for his provocative black-and-white cinematography in the film, and would later be invited to become a member of the ASC. He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1993.