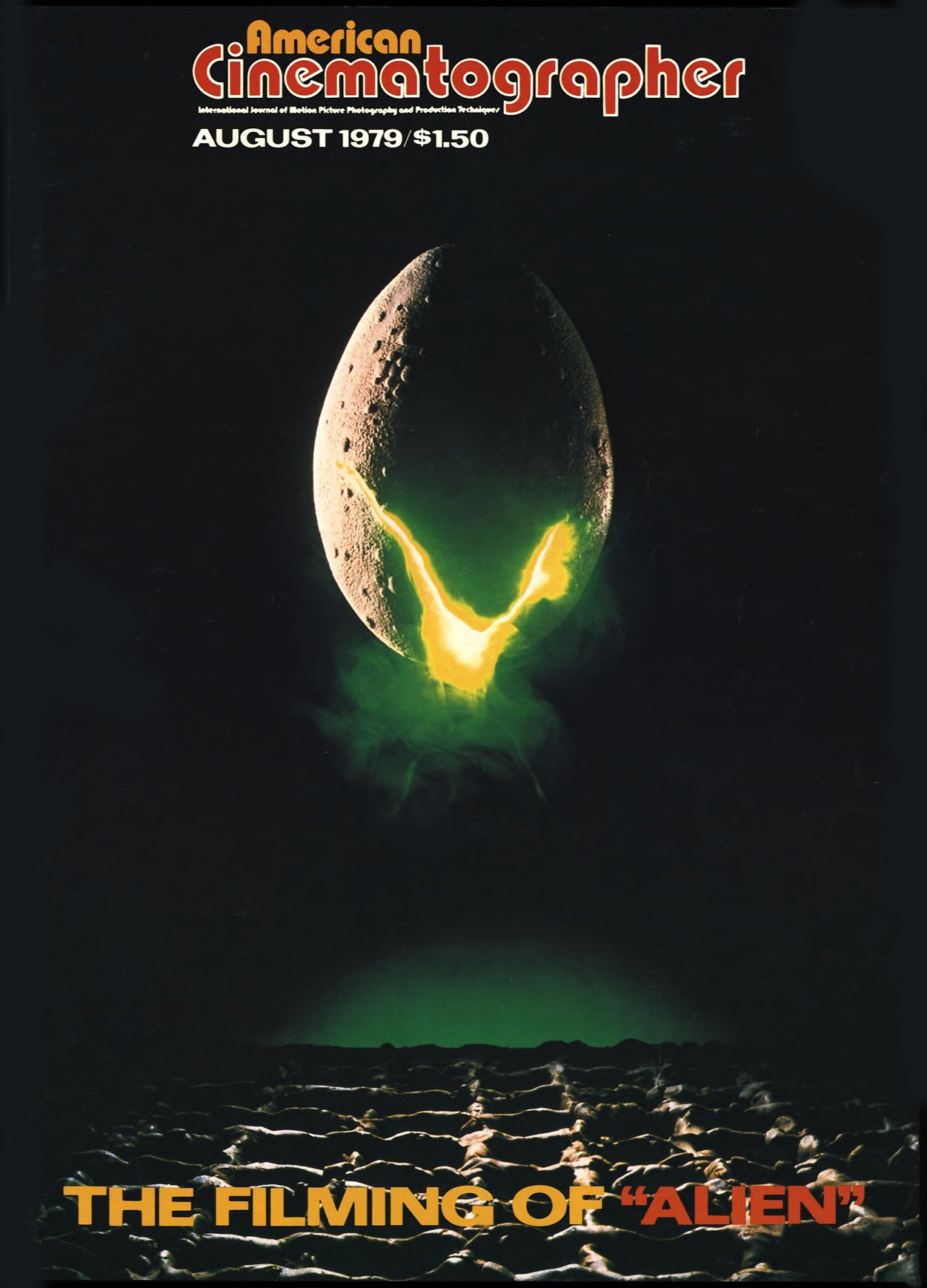

The Filming of Alien

Ridley Scott talks about the hundreds of problems involved in taking an essentially fantastic idea and making it real on-screen.

When, as a director, you are offered a project like Alien— or any science-fiction film, really — it is an offer to start with and becomes a confrontation afterwards. The problems gradually emerge, and on Alien there were many, many, many of them. People ask me, “What is the single individual problem you had the most difficulty with?”

There wasn’t one. They were all difficult — and if you had let one of those problems slide by without solving it, a weakness in the impact of the film would have been the result.

I want to emphasize that I don’t think of Alien as an “effects” film. It’s not. I had decided in advance that it wouldn’t be an effects film, in the usual sense of the term. I think there is a danger in that sort of designation. All too often what people refer to as “effects films” won’t stand on their own, because of weak story or weak characterizations. I felt that Alien should be primarily a film with a story about seven real characters — and that this would be the strength of the film, not the effects.

“In the beginning I didn’t quite know what I was going to be getting myself in for, because I’d never gotten involved with effects before. I had never really been a science-fiction fanatic, although I felt that at some point I would like to have a shot at such a subject.”

— Ridley Scott

Now, it so happens that you can’t do a film like Alien — which does involve effects — without making sure that they are going to be up to the standard set by Star Wars, Close Encounters and the Big Daddy of them all, 2001: A Space Odyssey. One has to try to reach that level. The best thing that happened to Nicky Allder and his effects team was having a strong story and characters who were very strong. These elements were essential to creating a “real” film.

As for the problems — there were thousands of them, all happening together, but I feel that we had probably the best outfit I’ve worked with in 10 years of filmmaking. They had the kind of reliability of someone saying, “Yes, I’ll make it work by such-and-such a date.” And, Bingo, it happens! That’s pretty rare, but they were an absolutely amazing outfit. A lot of them were sort of artists in their own right, even though they were dealing with equipment and things like that. There’s a kind of free-thinking in Nicky’s Allder’s mind, for example. You can see him piecing together the problem you have presented him with. Then he’ll say, “Oh, yes — I can use a little bit of this and a bit of that.” I found him ordering 12 memories for a tracking dolly he had devised himself. He thinks in very simplistic terms: “I want 12 memories — one for pan and tilt, one for diagonal right, one for diagonal left, etc.” There is that great simplicity that one usually finds in the great artists.

In the beginning I didn’t quite know what I was going to be getting myself in for, because I’d never gotten involved with effects before. I had never really been a science-fiction fanatic, although I felt that at some point I would like to have a shot at such a subject.

When the script was offered to me, I went to Hollywood to meet the producers and discuss changes and budget. The proposed budget was $4.5 million, which was impossibly low for that particular movie. In London we had been doing a kind of cost breakdown of the script and had estimated the budget at about $13 million, which was far too high for 20th Century Fox. I used to be an art director, so I had the tedious task of storyboarding the film, which took five or six weeks, while everybody else was budgeting along behind. We came down eventually to $8.5 million and went forward from there.

The project seemed to gather momentum very quickly. Even while we were still budgeting and there was a sort of on/off feeling, we were talking to cast and things like that, because an impossible starting date — only four months off — had been established. That was ludicrous in terms of preparation, especially since we were trying to press-gang the best people, who were already sort of semi-involved with something else. But getting the best was absolutely the key to making the film.

The storyboard I did was essential, because the whole thing has an abstract spirit of intention until somebody sits down and says, “Physically we are going to do this and we are going to do that and it will look this way.” You can’t budget on an abstract basis — which means that, in the very early days, you’ve got to get very specific about how things are going to be. For example, it helps tremendously if the effects man knows how a sequence is going to go. He is able to very carefully structure around that, knowing what things he can legitimately hide.

Once we had done the overall, sort of general storyboard, there was then drawn a storyboard for each day of shooting. That day-by-day planning added up to a four-inch slab of storyboards. It was just huge. Drawing it all out like that is very tedious, but necessary in the sense that while you are drawing you are actually helping yourself think. It’s like a writer with a problem who, by doodling, can focus his attention and get things flowing. I’ve seen voluminous storyboards on King Kong and The Hindenburg, both of which relied much more on opticals and mattes than our film did, but they certainly simplified matters. In Alien there were no mattes or opticals or cheating — just pure physical effects, which seems to be the best way of achieving reality.

To explain my method for choosing a crew, and particularly the cinematographer, I have to backtrack a bit in my own career. I came out of BBC television where I had been doing drama series and drifted into advertising. I had found television quite frustrating because there were so many people involved in the making of it that it eventually drove me mad. You could never quite get to the point of visual perfection that one wanted to achieve. Also, working with tape, it was almost impossible to get a satisfactory result. Even if you are shooting for television, you’ve finally got to go to film in order to get something that is really successful. Ten years ago I entered the television commercials field, which was then relatively new in England. I worked in it for a year as an art director, then started getting offered advertising commercials to direct.

At that time — 10 years ago — I had a lot of trouble dealing with what I call “traditional feature cameramen” because they underestimated the whole field of advertising film. They would, therefore, just do it and walk away from it. I found myself having to hire feature cameramen who weren’t particularly interested and I got very frustrated by this. I then came across a couple of guys who were new to the field. One had been a rostrum cameraman (Frank Tidy) and the other (Derek Vanlint) had been a still photographer with a studio in Soho, but wanted to get involved with film.

I suddenly found it much easier working with these cameramen because I didn’t have the huge pressure of a very experienced feature cameraman who was trying to employ a very heavy, big feature shooting technique. I liked a more natural approach to lighting for the sake of realism.

So I’ve worked with Frank Tidy and Derek Vanlint for 10 years and we’ve gotten to know each other very well. All this time, while making advertising films, I had it in the back of my mind that I would at some time be doing feature films, and the people working with me have, in a funny sort of way, come along the same route. Frank Tidy photographed my first feature, The Duellists, and Derek Vanlint, of course, photographed Alien.

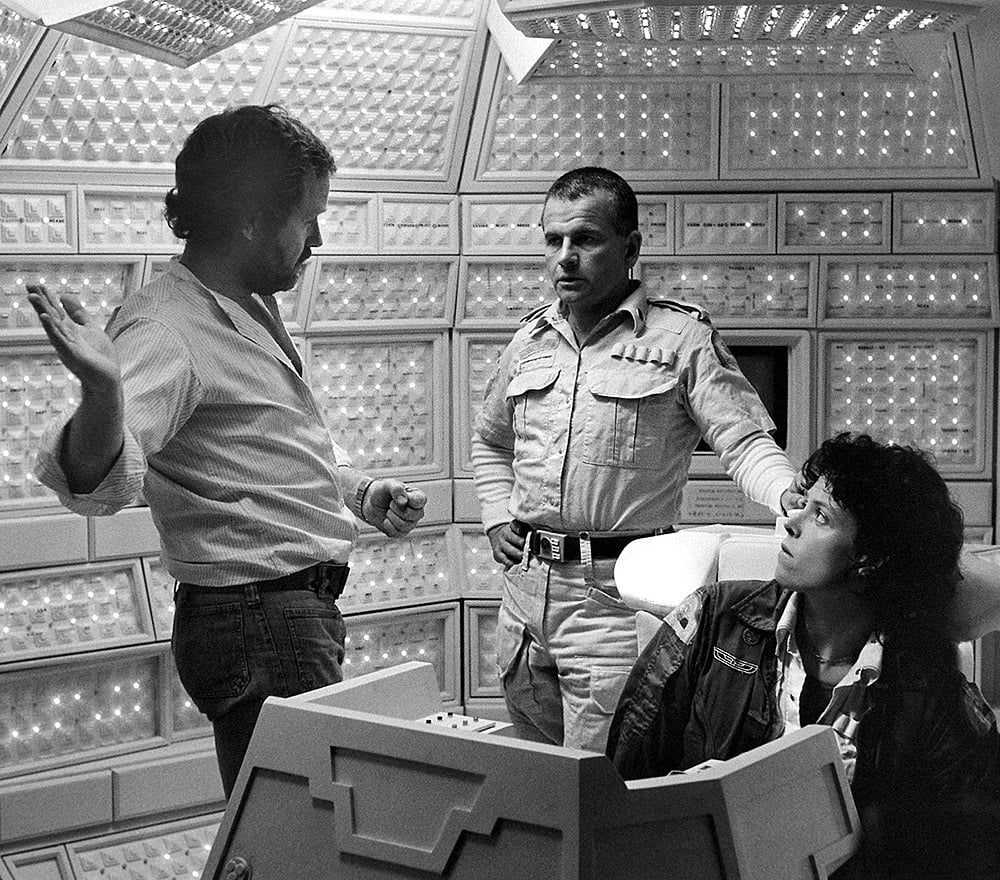

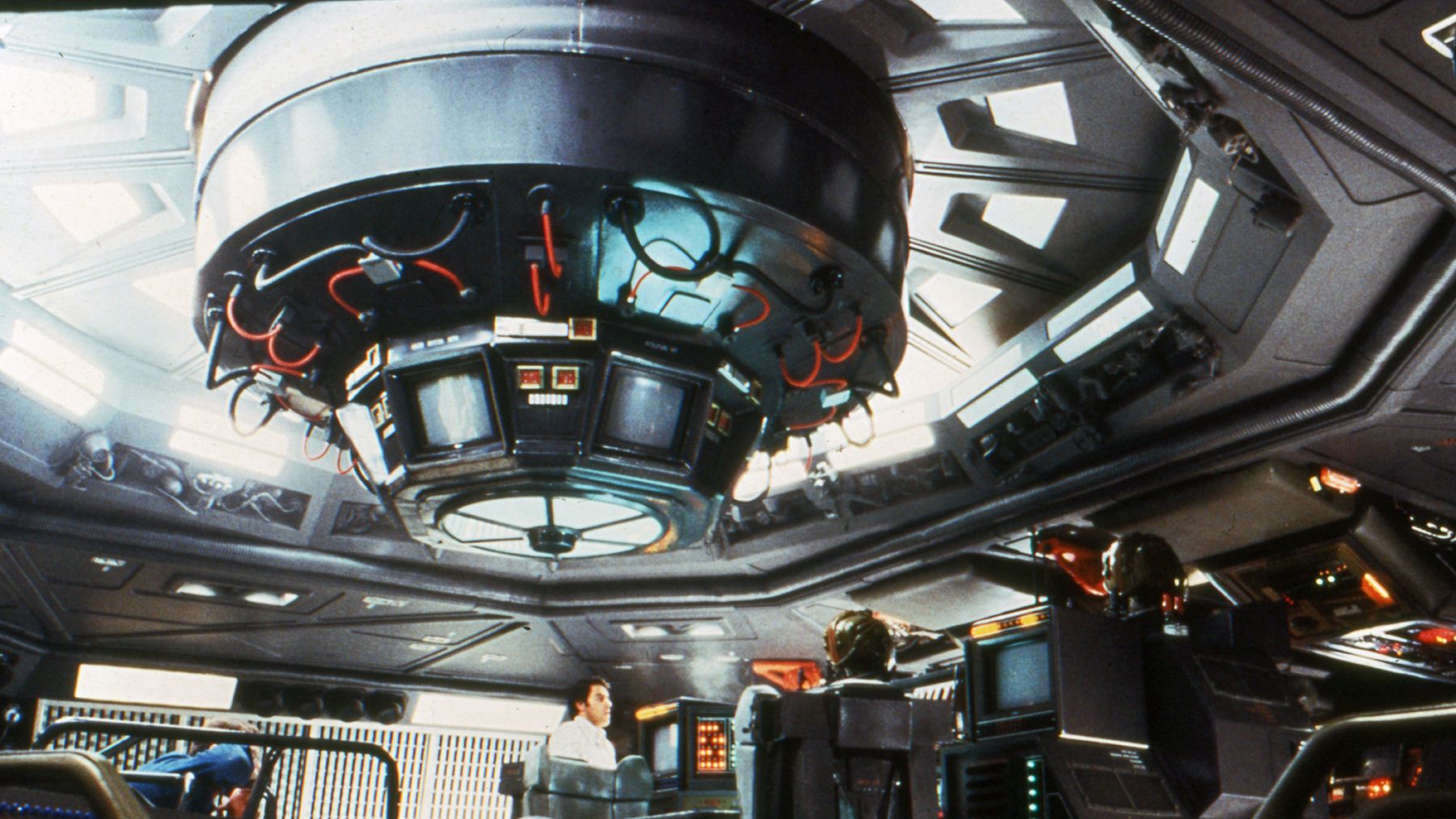

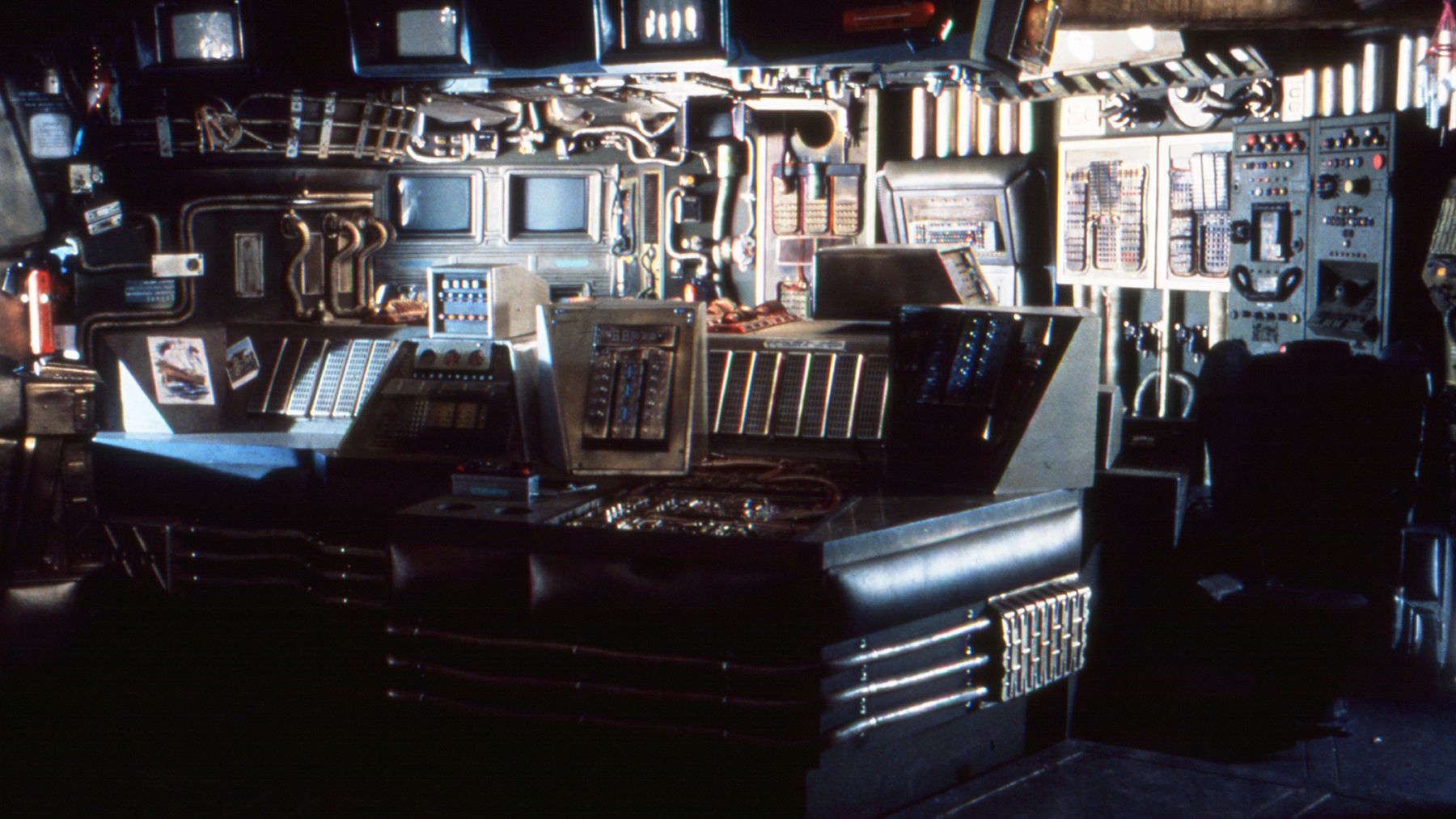

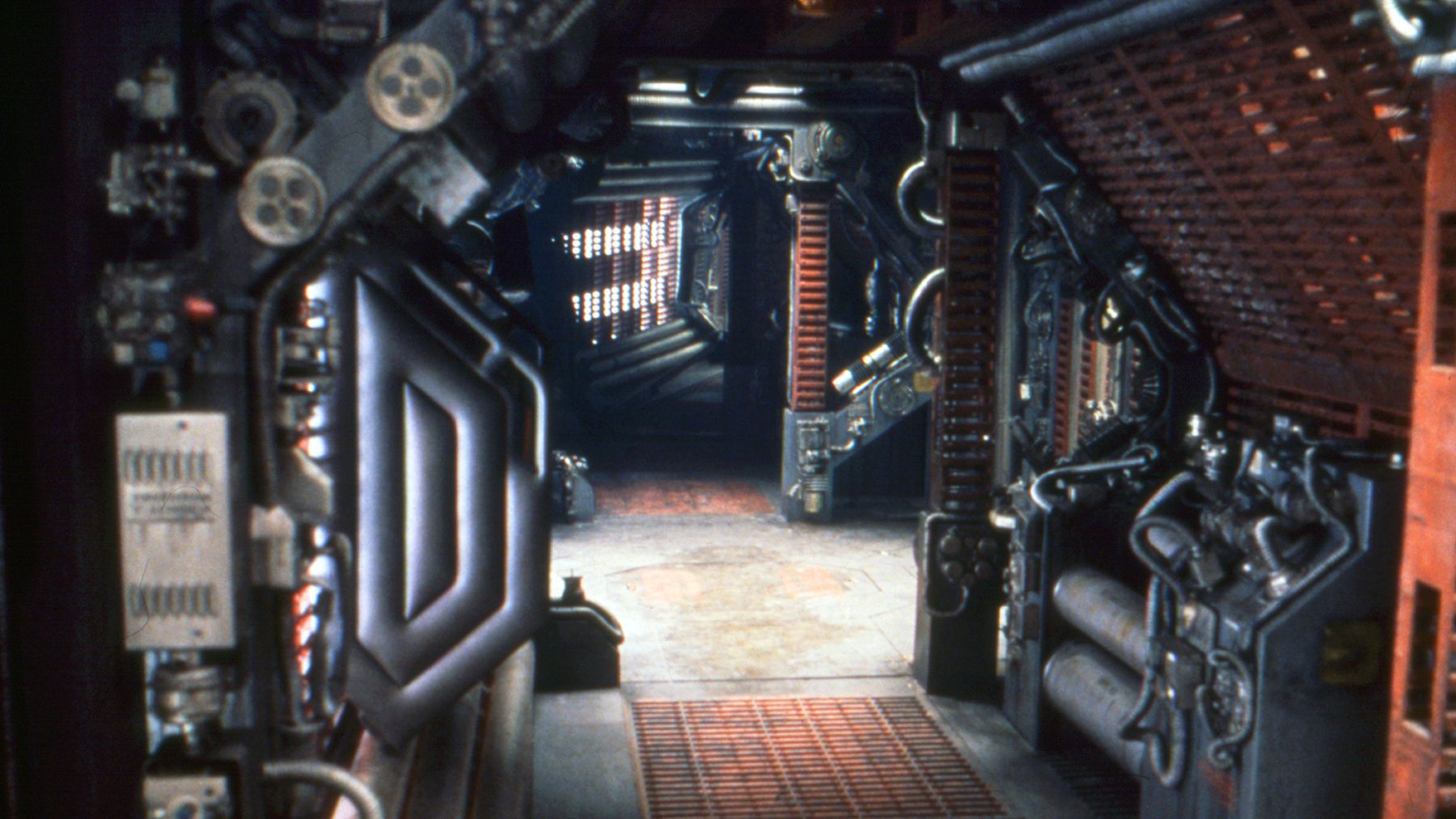

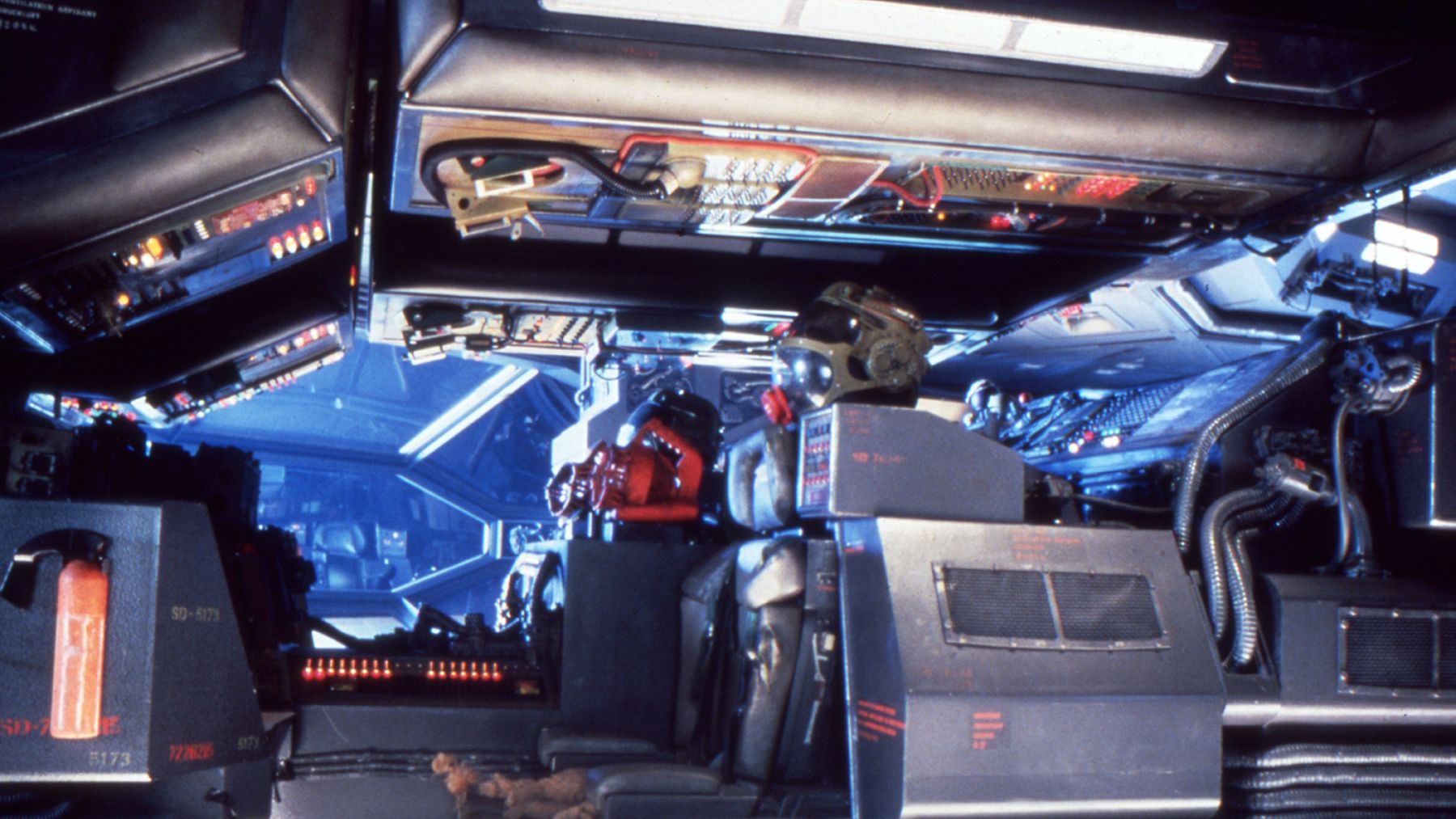

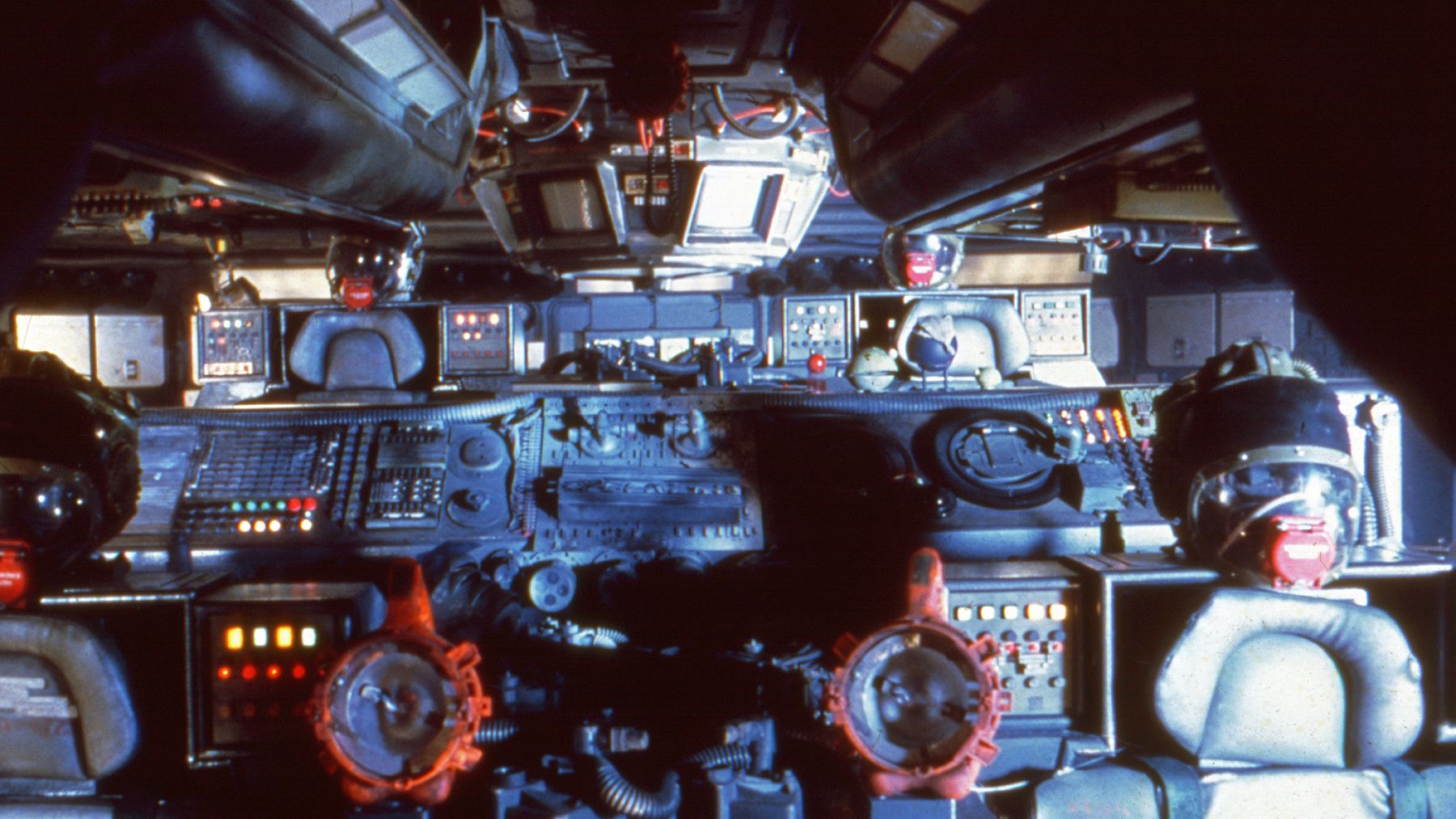

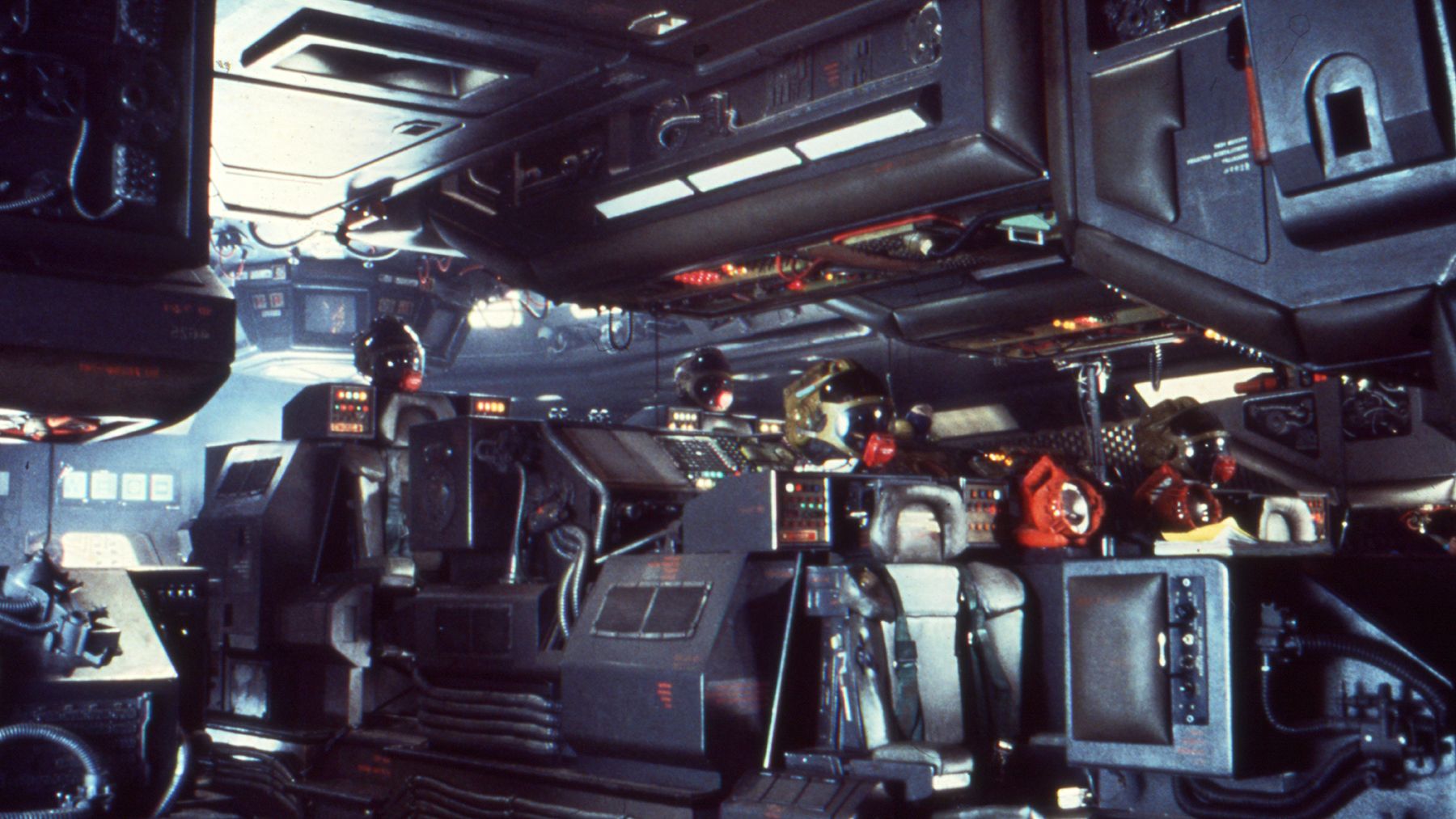

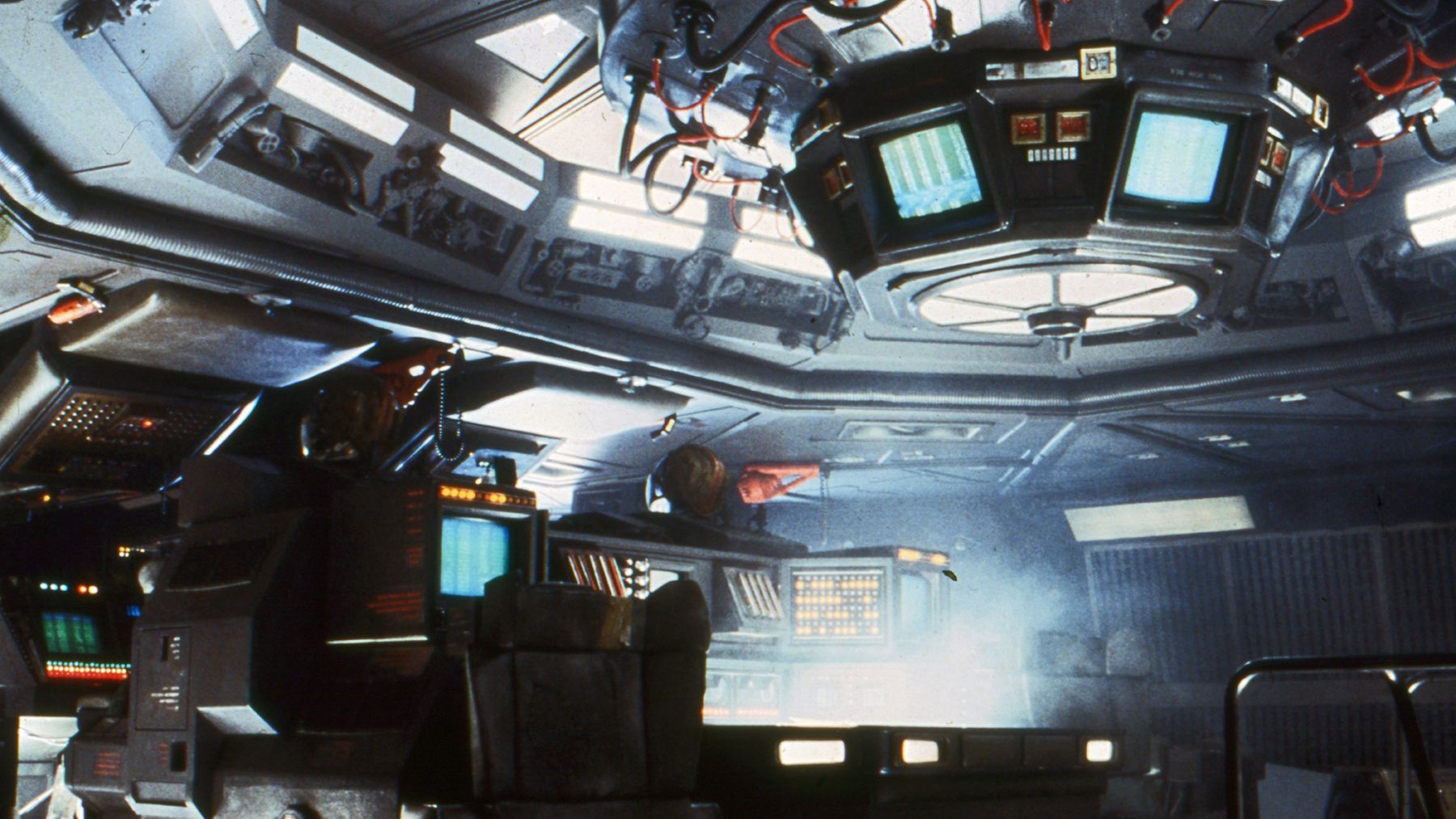

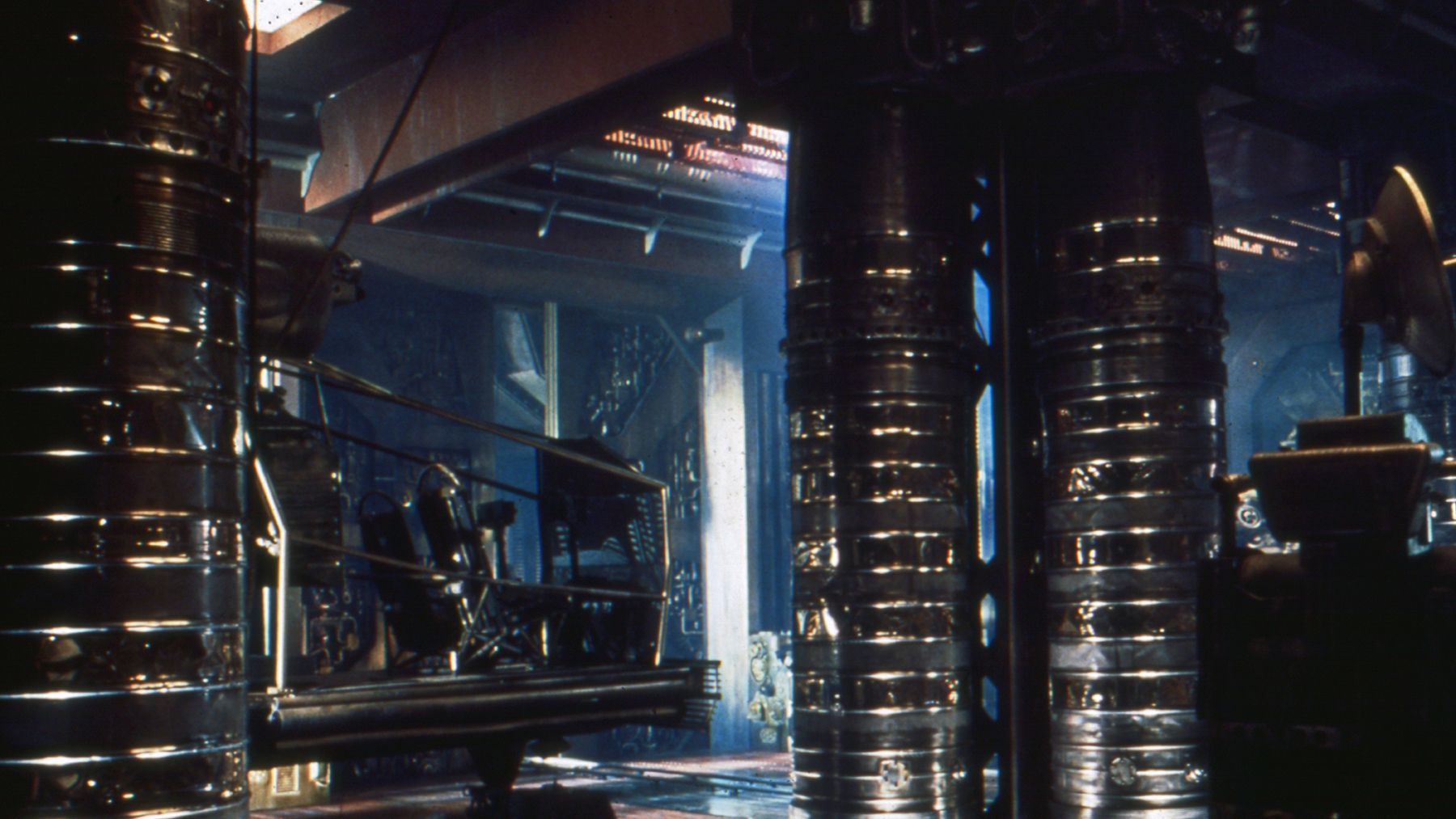

In evolving a visual style for Alien (most of the action of which takes place inside the spaceship), there were certain special problems. If you are dealing with conventional rooms — whether they be Napoleonic or modern-day New York or whatever — you have a definite place that your light source is going to come from — normally your windows or the lamp on the table. In this instance there were no such sources.

I originally had the idea of lighting everywhere at once, so that I would have total freedom of movement through the corridors of the spaceship. It was a big set and I wanted to avoid the process of setup-by-setup shooting — which finally is the best way, actually. I loved the way 2001 looked, but we didn’t want to emulate it by going high-key with a lot of overhead light coming through ceilings filled with plexiglass. We wanted our lighting to be very directional and, for the sake of the mood of the story, rather low-key, gloomy, melancholy, depressing.

So we made up a section of set and started experimenting. We got into a terrible tangle of variations because I wanted to use some tube [fluorescent] lights, but mixing them with tungsten lights and an occasional Brute meant that you had three different types of light and Derek Vanlint was nearly driven mad trying to get the right combination of filters to balance everything correctly. It was murderous, because even going by the book didn’t quite work out. We went through two or three weeks of just having someone standing in the corridor, changing the whole combination of lights and filters, but we could never quite get a satisfactory balance. It was always a little off.

Also, my ideal notion that, by lighting the entire set, you could put an actor anywhere in it and, with a little bit of flagging, be ready to shoot just didn’t work. It started to look as though we were shooting TV. Both Derek and I were unhappy that we just weren’t getting what we wanted visually, and also we were tending to throw away a lot of the niceties of the set. So we just went back to normal shooting, which was basically: find your setup, have whatever bulb combinations you wanted for set purposes, but light the scene with more conventional equipment. Frankly, I prefer that method — and certainly for a project like this. It was better than trying to out-think yourselves simply to move along at great speed.

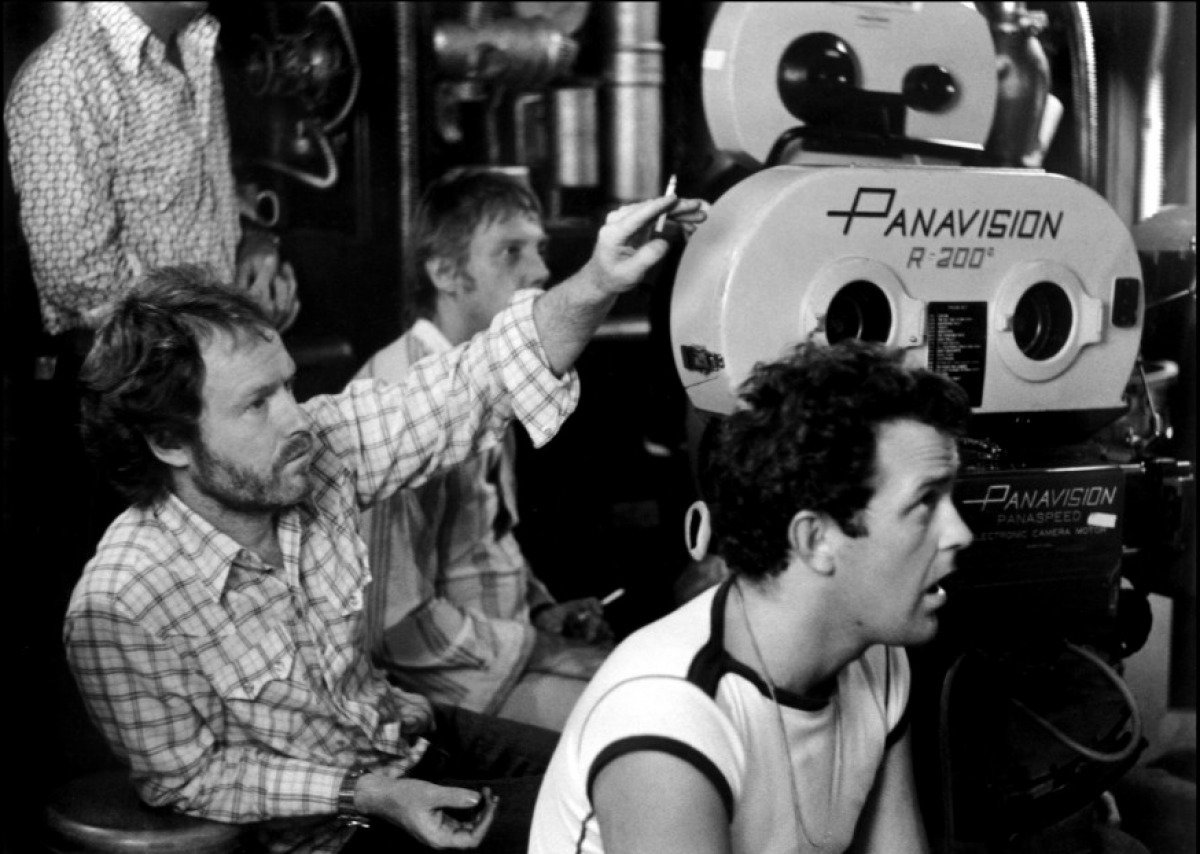

To Derek and me — coming from where we have come from — the visual aspects of a film are terribly important. They’re not everything, but they’re a hell of a lot. A cameraman ought to be involved in the sets, but frequently he isn’t. He often just walks in, looks at the set and lights it. But Derek was drawn into everything, including colors, textures and that sort of thing. In the filming of commercials we’re used to incorporating everyone into the planning process, so that everybody will know what everybody else is doing and everybody will be working off everybody else for the visual aspect of whatever the subject is. That’s a honing process, and it’s as important to me as the actors and the script.

There is an immense schedule pressure in the making of feature films, but the process of feature-making is, by its very nature, slow. The more you go for quality, I’m afraid, the slower it gets. There’s no point to shooting simply to stay on schedule. You’ve got to see it through the viewfinder, and if it’s not there you haven’t got it. That quite frequently can become a nightmare for the director as well as for the cinematographer.

“It takes an army of dedicated people to make a feature film — and on Alien we had a marvelous army.”

Making a feature is marvelous, I think, but it’s a nightmare while you’re doing it — a sort of love-hate process. It was that way for me and for Derek, as well, on Alien. I think it’s very important to have the sort of relationship with a cameraman where you can go into the corner and say, “It’s not working today, is it?” You can then discuss it quite calmly and find out why it’s isn’t working, what you’re doing wrong. It is usually a very private thing between these two individuals only. It would be frustrating to have such discussions with actors sitting and waiting, but I’ve discovered that the best way for me to work is not to have the actors near the floor at all when I’m lighting. I’d rather just have them out of the way, in their dressing rooms reading or sleeping, because there’s nothing worse than having actors standing around and waiting. It drains them. You can see the adrenalin falling out of them while they are hanging about, so we are usually very careful about scheduling actors in.

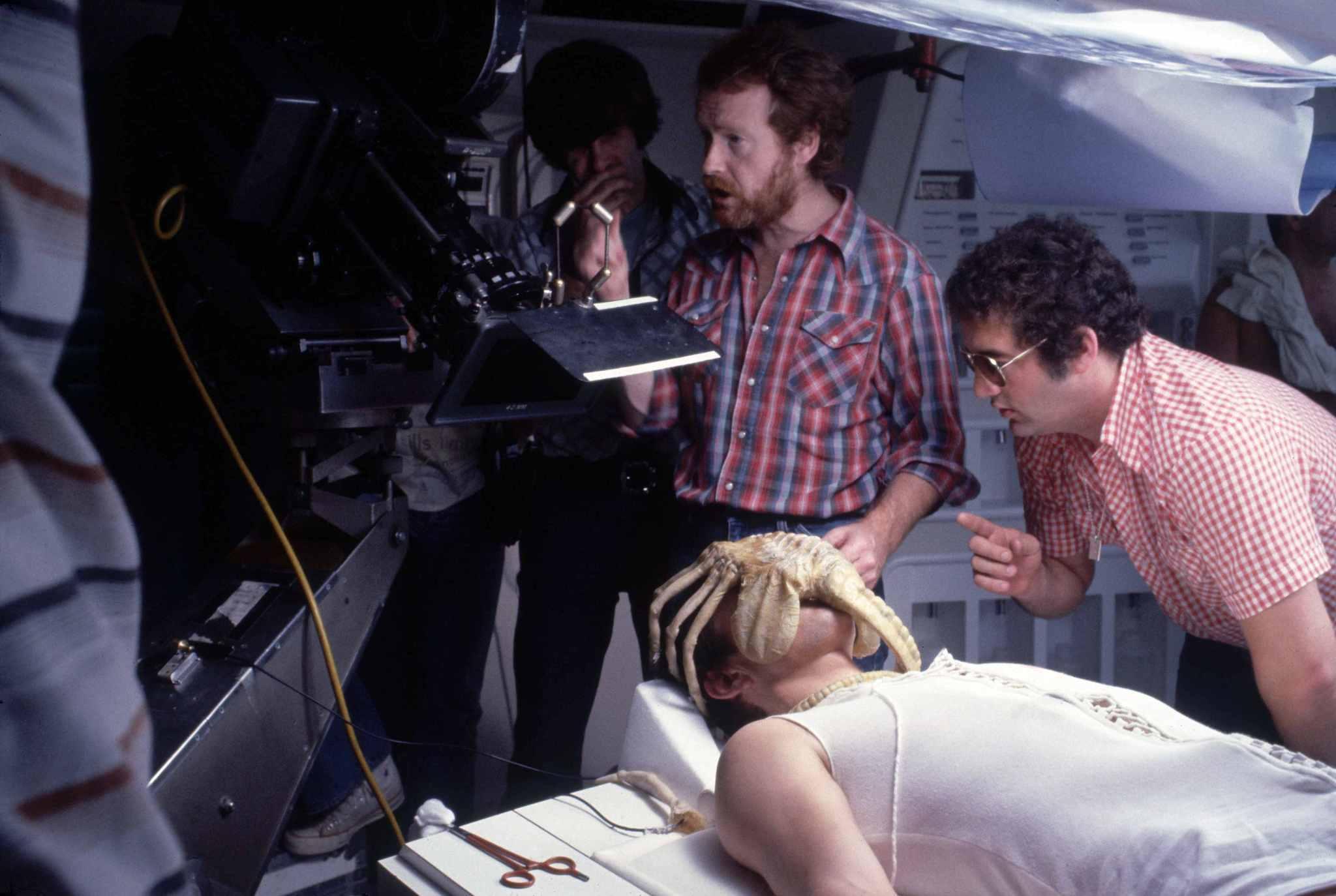

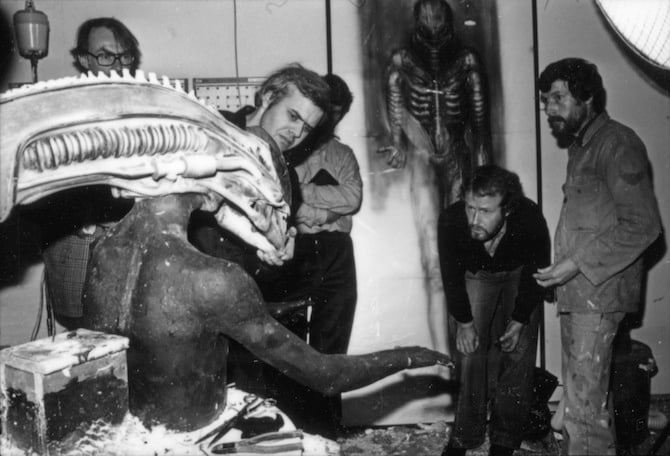

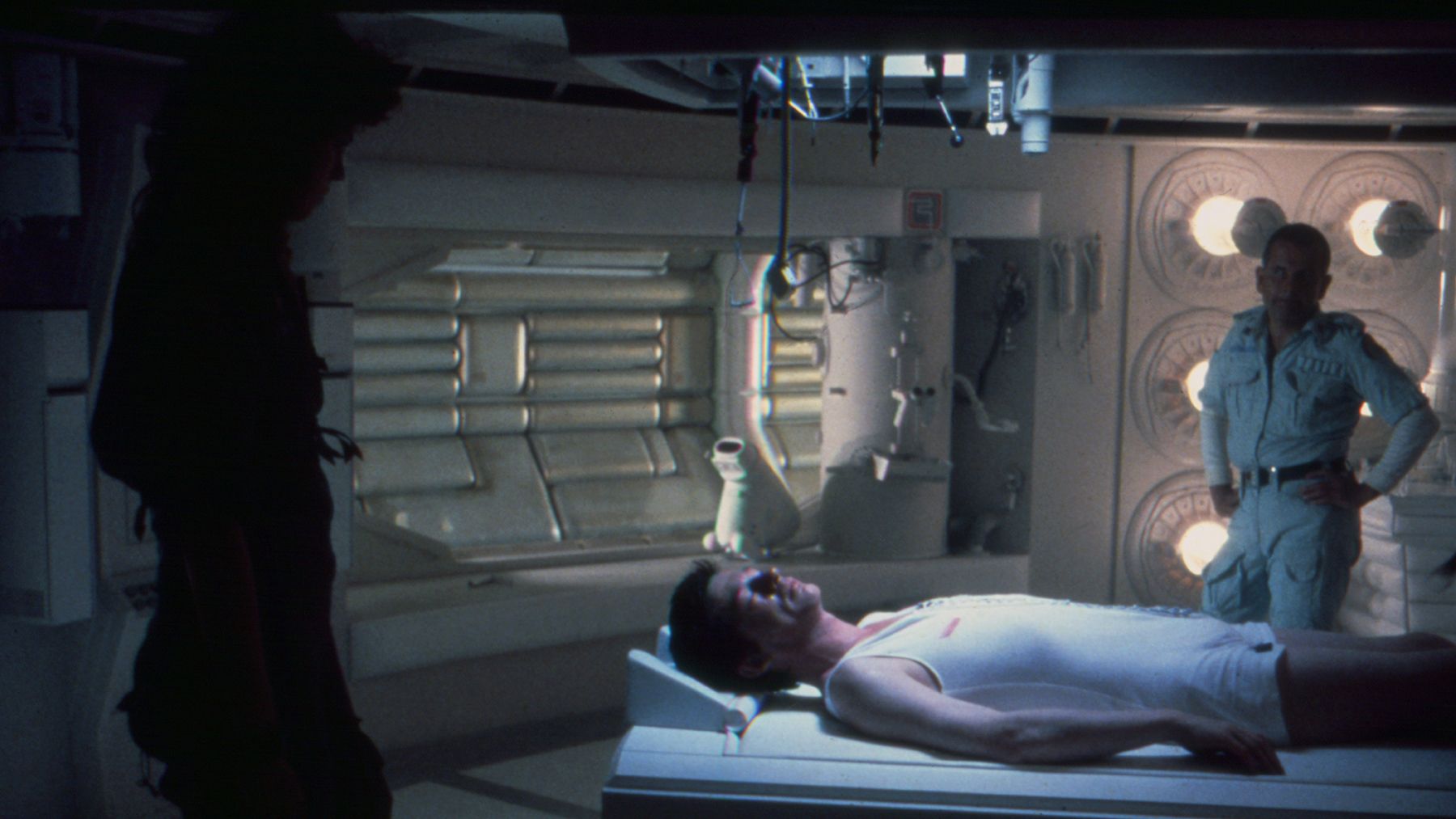

In the making of Alien, we were, of course, confronted with something more than actors. Once you accept a script like that, the next question that comes up very fast is: What form is the creature going to take? In this case the problem was made four times as difficult, because the Alien changes in varying degrees on several occasions. Therefore, you were dealing, in this instance, with four different entities. One could argue for months about what shapes they were going to be.

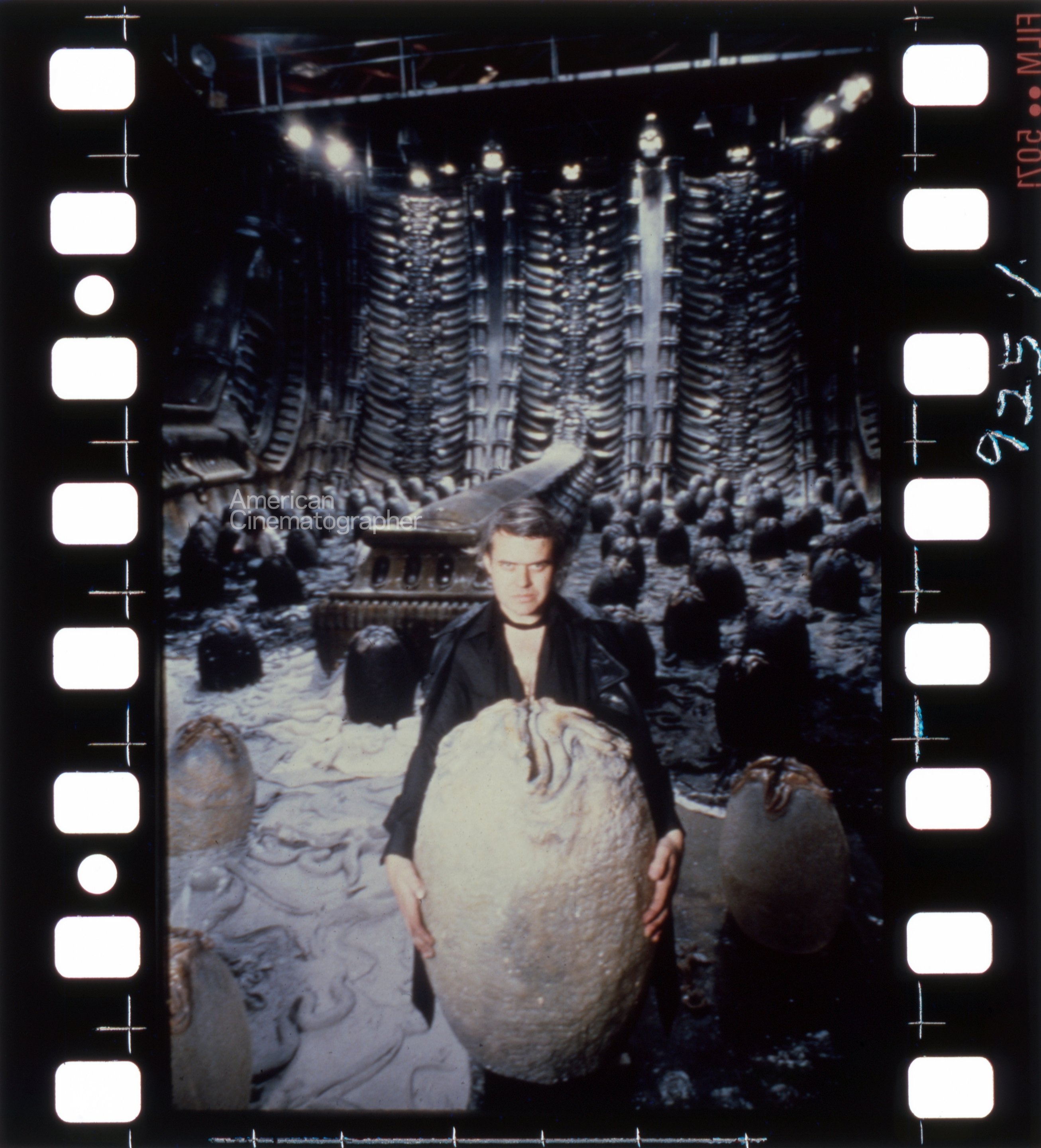

We went and saw visuals of what had been done before, where you get the old Blob crawling across the floor, or a dinosaur with claws and bumps and warts, and I said, “Oh, God — it can’t be that!” but the form that the Alien would take became my primary concern, and when I went to Los Angeles I saw some artwork in a book by H.R. Giger. There was a half-page in that book that was just amazing. I’ve never really been so shook up about anything. I just said, “This is the basis of the creature.” From that point on we had a very factual, very specific, superbly rendered representation of what the Alien would finally be. It was valuable to know what his final stage would be, because then you could work backwards and biologically create stages of his development. In this case, it was necessary to do that. You had to be, in order for it to look real. You had to develop a basic understanding of how it would work, how it would move. It’s the same with any biological sort of creature that you are constructing. You’ve got to think of it in anatomical terms.

In this case we went from the final stage of what he was and jumped back to what he would look like as a baby. There had to be a certain shape related to the final stage, and that’s partly how we arrived at the nasty one. The thing that sprung out of the egg — the “perambulatory penis,” as we used to call it — is the father. It is an abstract entity, in a sense, because all it does is plant a seed. Once having conceived, it dies, and the next generation takes on characteristics of whatever life form it landed on. It could have been a dog, in which case the Alien would have taken on a dog form. The result is a combination of two elements: the original creature and whatever host it uses.

During the course of designing, the Alien went through many changes, becoming more refined and more animal-like. I wanted it to look animal-like rather than fantastic — because the word fantastic means “not quite real,” and I wanted it to look real.

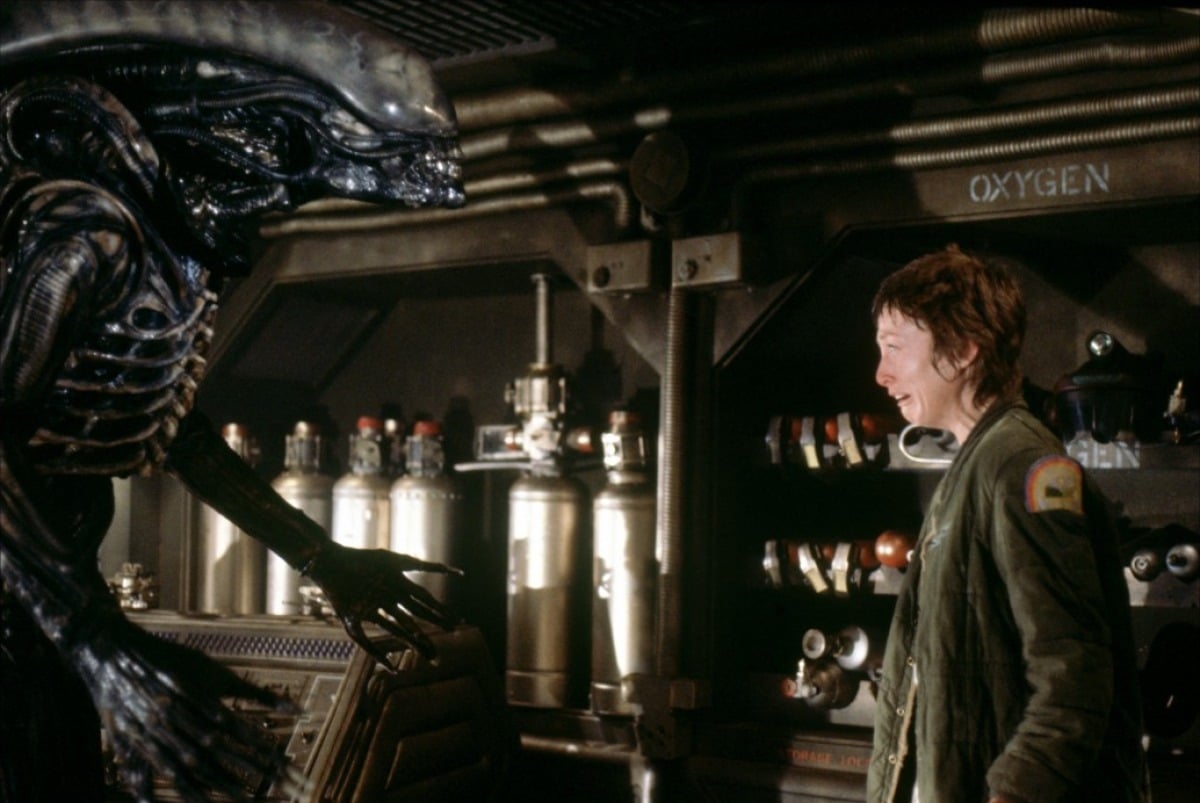

Designing the creature in all of its phases was a difficult problem — getting the forms and textures right and all that — but getting from the design on paper to the actual thing was the worst area. What may look great on paper you may never be able to get to look right when you construct it, or you may have such a colossal weight problem that it becomes an impracticality. The mechanism of how we would make the face and head function became just too much, in the short time that we had, for Giger to tackle. We had put a workforce of people around him that would come up with all the elements involved in the derelict spaceship, the interior of the derelict, and the Alien. Sculptures and working scale models of these would then be handed to the Construction Department, which would have to build them and make them work. Every process was difficult, and to keep it within its budget was even more difficult.

At this point, Carlo Rambaldi, who is a mechanical genius, came onto the project. He was an industrial designer originally, so there was a great deal of practicality attached to his artistry. He looked at the head, loved the artwork and the whole intention of the film and, even though he was up to his eyes in other things, he was somehow able to say, “Okay, I can get involved in the face and make various things happen.” and so, he came in for three or four weeks, working with Giger.

Carlo Rambaldi designed the mechanics of the head, made the lips work, made the jaws function. Normally you can’t stand to have the camera take a close look at things like this, but it was so good and I was so pleased with it that I just did a huge closeup on it.

I feel that in the process of feature-making, the director should be involved straight through — and so I have been. The editor, Terry Rawlings, was cutting the film behind me all the way. As I was shooting he was editing, so every night I was able to see what was happening. We would discuss it and he would make refinements, then carry on making assemblies as the footage was coming in. This worked so well that eight days after the end of shooting in October we were able to show 20th Century-Fox a two-hour and 22-minute cut.

Of course, long before that stage was reached, the people at Fox had got wind of the fact that we were working on something special and I think that it grew in their estimation from the original $4.5 million film they had planned to something that might really have a shot for them the following year. And so, very soon, the May 25 release date became a fact that we had to stick to. Consequently, Fox then kept a very close eye on it all the way through.

We had to keep showing cuts four times during the filming — leaving huge gaps here and there for special effects shots and miniatures. The Fox people were fully convinced that they were going to run the film in theaters on May 25, so, at whatever cost, we had to get it out. This meant that at the end of shooting the principal action there was no let-up whatsoever. I had to go crashing straight across from Shepperton to Bray Studios, where the effects and miniatures were to be shot. Derek had finished at Shepperton and now I was joined at Bray by the miniature effects director of photography, Denys Ayling, and special effects supervisor, Nick Allder, who came across with his floor effects unit from Shepperton.

I got involved with the model-making and shooting and found it to be just amazing, really interesting. I had my editing rooms at Bray, so I was editing while still shooting. The process of filming miniature shots carried on right up to the last minute. You do it and it’s not quite right, so you do it again — and maybe again, until eventually there comes a point where you have to be practical and say, “That’s good enough.” The whole process was a railroad track right through to May 25. There was no let-up at all.

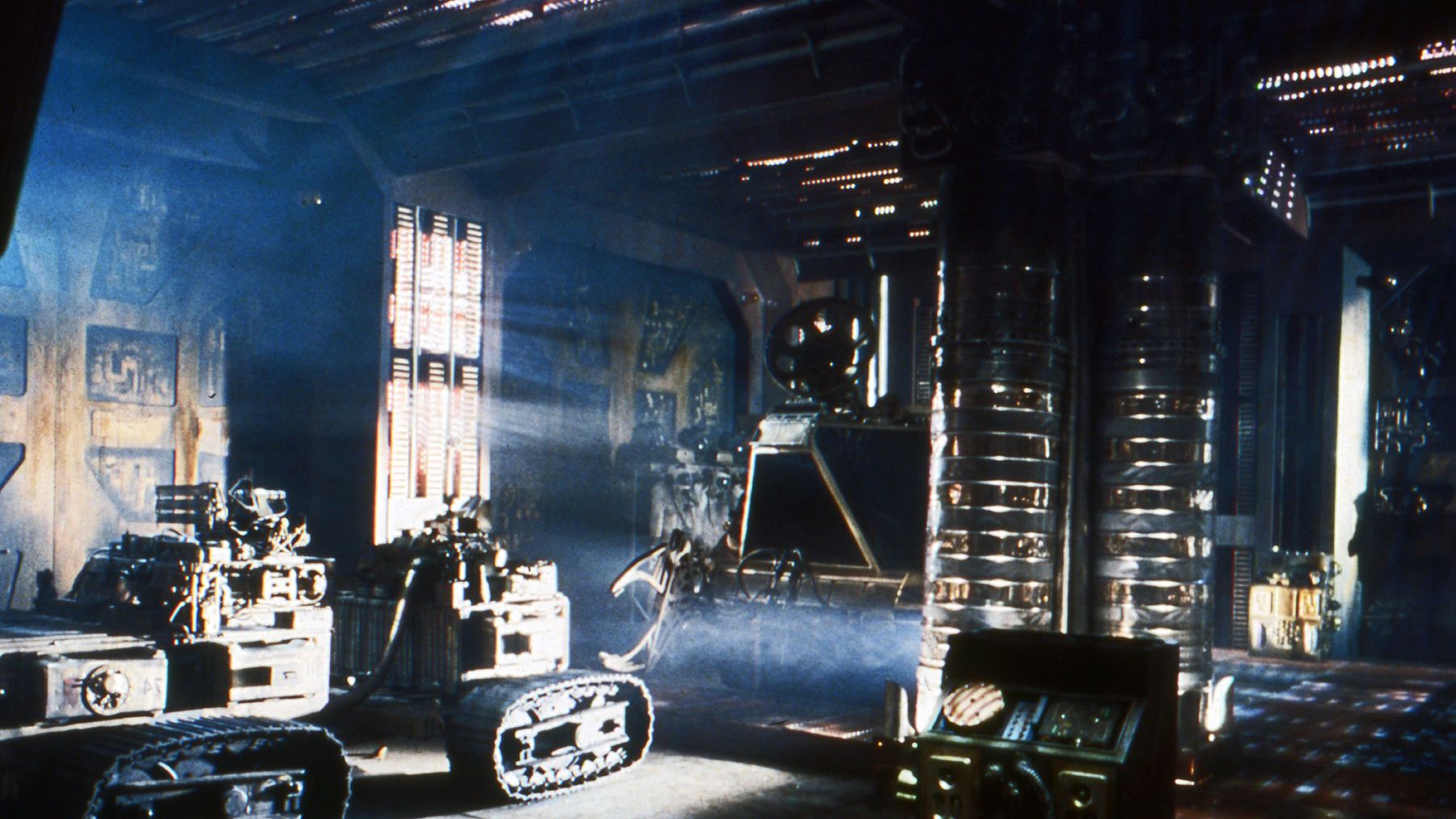

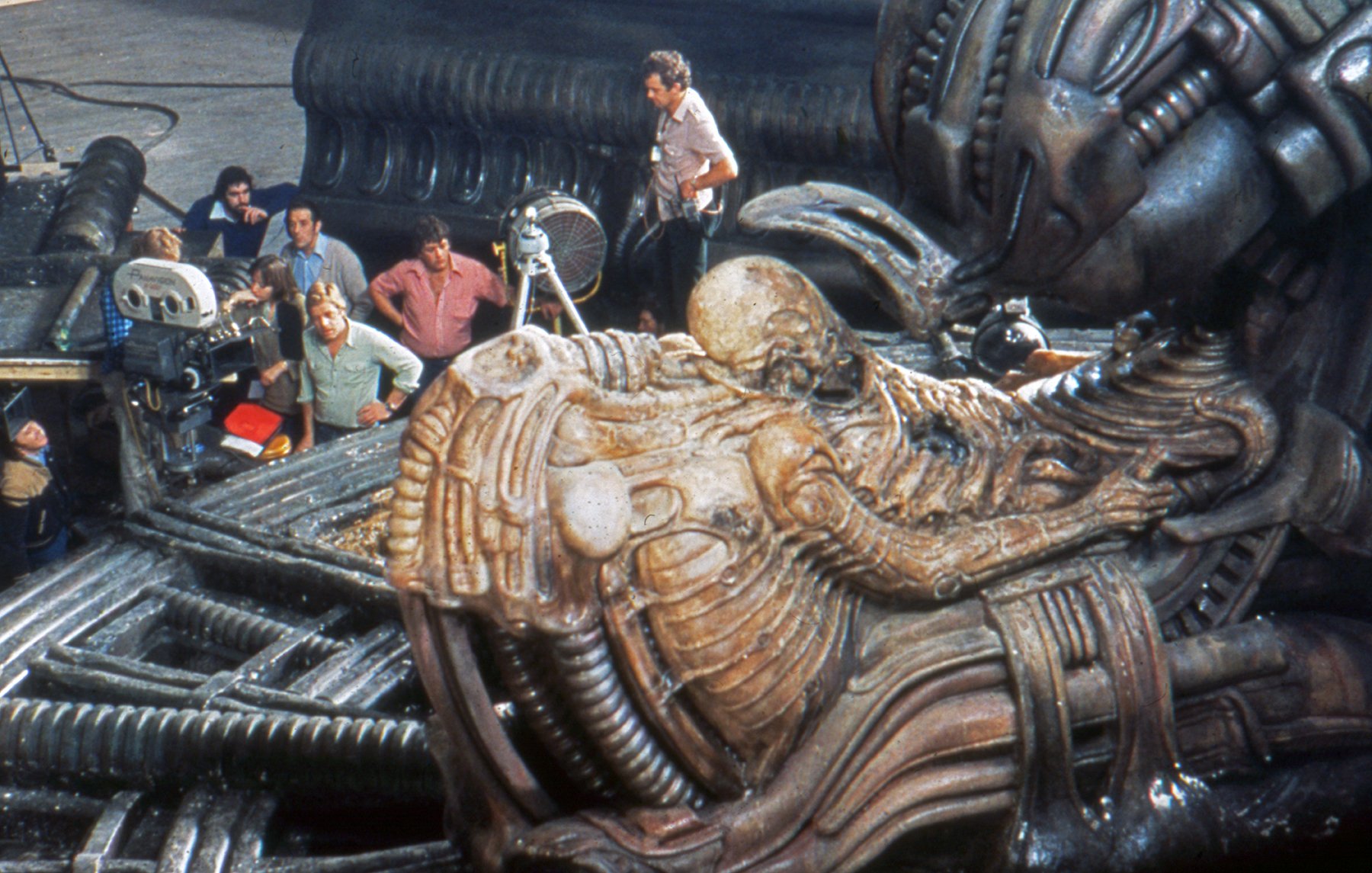

In the making of a film like Alien, there is a whole large group of individuals who tend to get overlooked and who don’t get enough emphasis really. The art department is a prime example. Their budget alone approached $2 million. That means that there was a huge amount of designing apart from the overall visual concept. Then there was the challenge of taking that visual concept and building it in the form of sets that will work on film. You are then actually constructing reality. That can be well done or it can be really badly done. I feel that in the case of Alien it was extremely well done.

There were several key people in the art department who worked closely with Michael Seymour, my production designer, who really steered the whole thing in terms of the way it looked and who designed an awful lot of separate things. It takes a lot of courage to handle a budget like that but he made it work.

Mike had two great guys working with him — art directors Roger Christian and Les Diley. It was Diley who really designed a lot of the exterior planet work and who was very involved in the model of planet terrain that was placed around the derelict spaceship. The derelict was a miniature about four feet across and it was sculpted by Peter Boysey. It was an absolutely superb sculptural work.

Roger Christian is a very special talent in that he is a master draftsman. There is an absolute art in what I call “graffiti” and it involves layers on layers of detail. It really is a form of graphic sculpture and everything looks like it works.

Then there was the construction manager, Bill Welch, who saved the film company a lot of money by holding strictly to the schedule and always knowing where he was in relation to his budget. The carpenter and painter units working under him totalled nearly 200.

It takes an army of dedicated people to make a feature film — and on Alien we had a marvelous army.

You'll find cinematographer Derek Vanlint's account of shooting the picture here.

Alien was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.