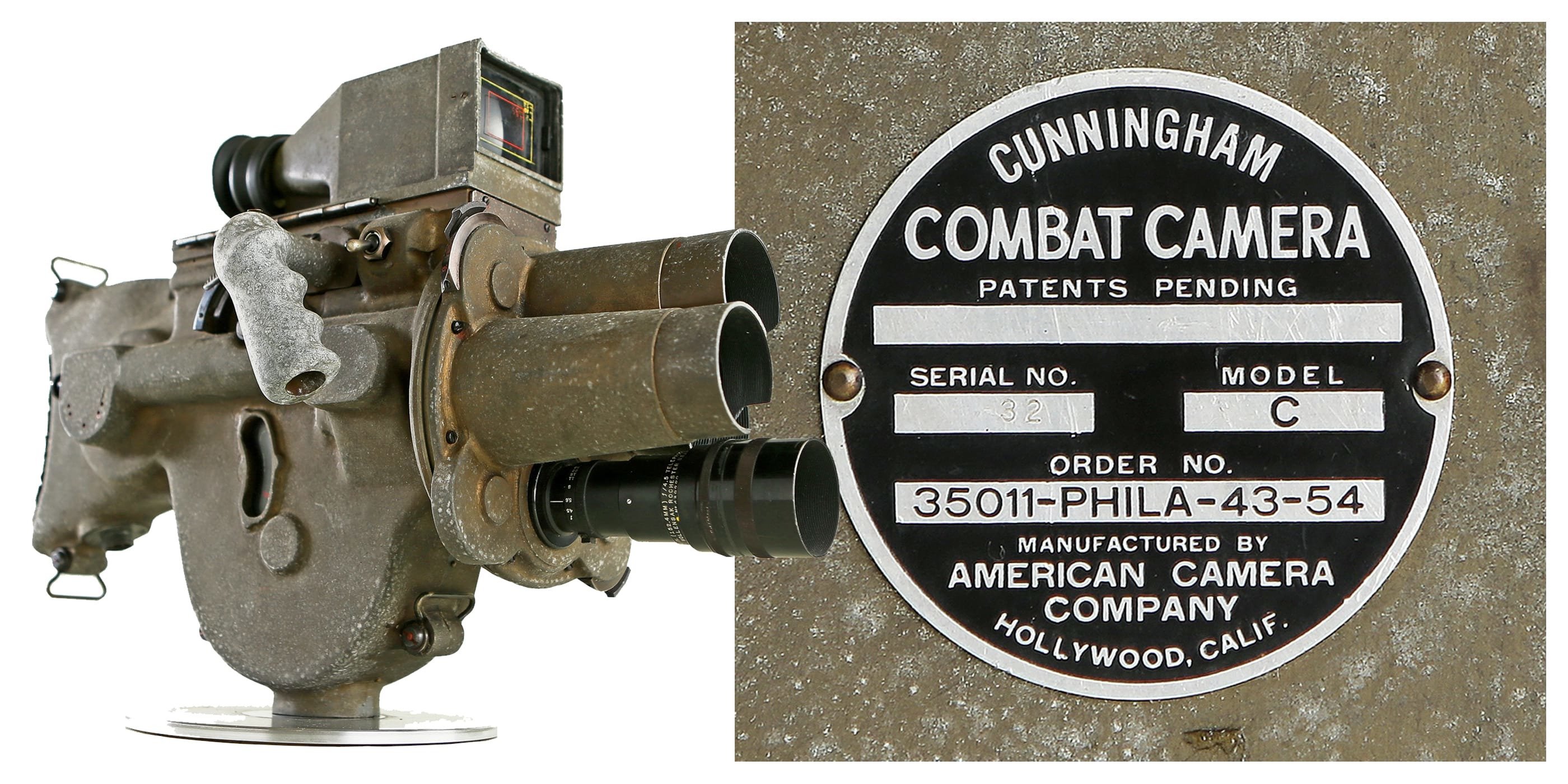

The First Real Combat Camera

A look at the new Cunningham Combat Camera, designed for the soldier in the field.

This article originally appeared in AC November 1942. Some images are alternate or additional.

By William Stull, ASC

This war, it becomes increasingly evident, is going to be fought almost as much with cameras as with guns. Already the U. S. Army, Navy, Air Forces and Marine Corps have put hundreds of cinematographers into the field to bring back a living record of this global war. By the time our forces grow to their full strength, the number of these combat cameramen may well run into the thousands. Their cameras will bring back actual records of front-line operations on land, at sea and in the air; some for purely tactical and technological study, and some as documentary-film reports to the American public.

Up to date, most of this military camera-reporting seems to have been done with the standard type of 35mm. and 16mm. cameras already available. But a camera that is ideally suited for normal studio cinematography, or for portable use by commercial and newsreel cinematographers under peacetime conditions may not necessarily be so ideally adapted to the use of a soldier-cameraman in a South Pacific foxhole, or a sailor-cinematographer on convoy duty off Arctic Murmansk, or an aviator in a Flying Fortress 30,000 feet in the air. For their use, a combat camera must combine sturdiness with simplicity, and foolproof operation with precision.

Just such a camera — probably the world’s first motion picture camera specifically designed for combat use — has been perfected by Harry Cunningham, one of Hollywood’s most brilliant camera designers. Sample prototypes are now undergoing tests by the various military photographic services, and when approved, the camera can be put into mass production immediately in any plant the authorities may designate.

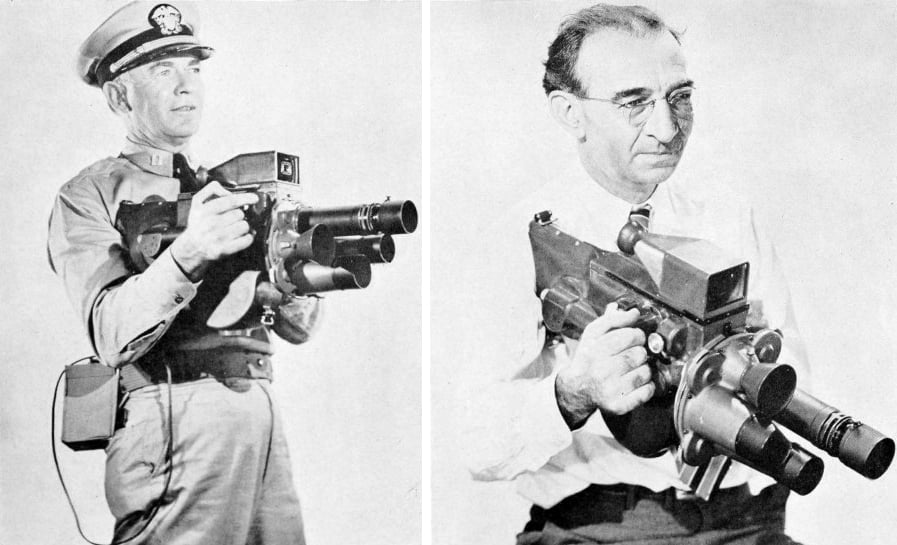

In design and operation the new camera is revolutionary. While it may be used on a tripod, it is designed primarily for hand-held operation. But instead of using the conventional box-form shape or single-hand support of most hand-cameras, the Cunningham Combat Camera is designed in gunstock form. It gains additional rigidity by borrowing the two-handed pistol-grip principle familiar in aerial cameras.

By means of these principles, the new camera is probably the steadiest hand camera ever built. In tests it has proven possible to hold steady on a stationary shot with a 10-inch telephoto lens!

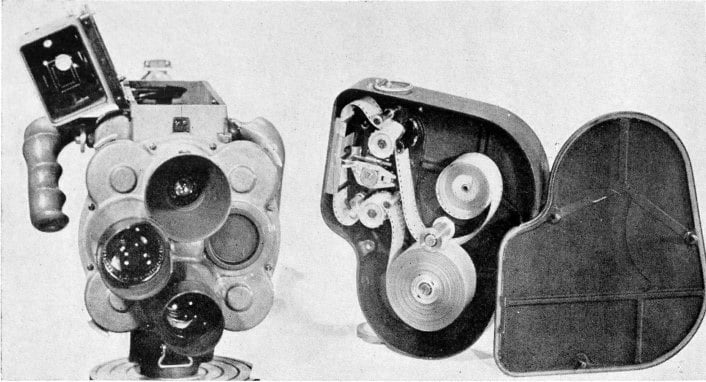

Though the camera in its present form uses 35mm film (a 16mm. adaptation will probably be made), it is of the magazine type — but refined to a degree of professional precision heretofore unknown.

The magazine contains the 200' film load, together with the entire film movement and take-up. The movement itself is an exceptionally accurate one of the professional pilot-pin registering type. Two sprockets are used, one above and one below the movement.

The take-up employs a uniquely simple form of compensating drive which eliminates belts, friction clutches, and similar complications, and is almost completely foolproof. As will be seen in the illustration, the film feeding out from the feed spindle passes under a spring-tensioned idling roller, the edges of which also contact the take-up roll. This is the sole drive to the take-up. Naturally, it compensates automatically for the differing sizes of the feed and take-up rolls: as one foot of film is fed from the feed spindle, it automatically drives the take-up roll to take up precisely one foot of film from the movement.

The angular deflection of this roller and its supporting arm also operates the footage-counter on the outside of the camera.

The film-magazine is of course loaded in a darkroom or changing-bag. This operation has been so simplified that it is easily done under such conditions. As a matter of fact, the Cunningham movement is probably easier to thread — even in the darkroom — than the conventional Bell & Howell or Mitchell studio camera movements.

The magazine is then simply dropped into the camera, through a hinged opening at the top. A slight downward push slides the magazine completely into place, and automatically engages the drive and footage-counter connections.

The camera is electrically powered. A small electric motor in the gunstock mount drives the mechanism, and is powered from two small radio-type “B” batteries which may be contained in a small pack clipped to the user’s belt. These batteries will power the camera for several thousand feet of film, and are easily replaced in the field.

Three camera speeds are provided — 16, 24 and 32 frames per second. The speed-control is a small button sliding in an arc-shaped slot at the left side of the camera. For checking speeds, provision is made for attaching a tachometer to the main drive shaft at the right side of the camera.

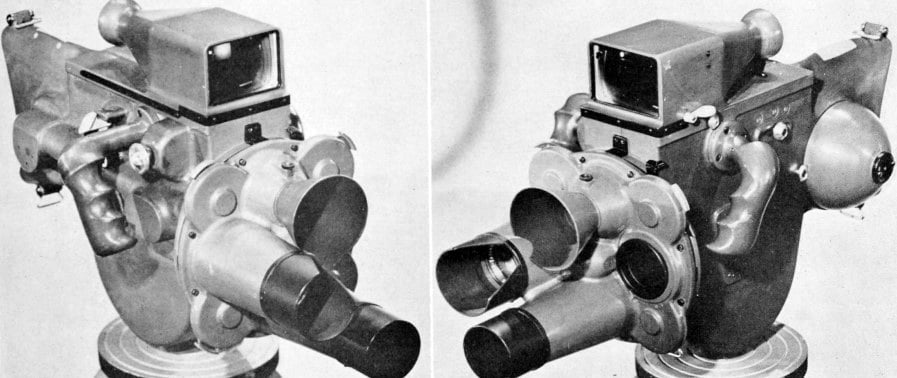

A four-lens turret is provided, and in the present model, 35mm, 75mm, 6-inch and 10-inch objectives are fitted. These were chosen by members of Commander John Ford’s Naval Reserve Photographic Unit as being the most useful range for combat camerawork.

Each lens is provided with its own diaphragm calibrations, operating on a quadrant adjacent to the lens-mount. In use, the operator need merely extend the index finger of his left hand from the hand-grip, to operate the diaphragm control. A finger-operated catch nearby releases and rotates the turret.

A single focusing control near the right-hand grip focuses all four lenses. For this, a single lever sliding along a quadrant is used. It may be operated by the thumb, or by the ball of the right hand, as may be individually convenient. Two focusing scales are provided along the quadrant, one for each of the two short-focus lenses. The two long-focus lenses are calibrated for only two points — infinity, for general use, and 35 feet, for slating identification.

The method of focusing is unique. Instead of rotating the lenses in their mounts, or moving the lens-board in and out with relation to the film, the film and magazine are moved in and out in relation to the lenses. This is made possible by means of a splined slip-joint between the main drive-shaft and the nipple connecting the drive with the magazine. In turn, it permits a much more rigid construction in the frontboard and turret, as the lenses can be mounted solidly, rather than rotatably, and the turret need only rotate to bring the various lenses into position. There is virtually no play perceptible in either the quick-change lens-mounts or the turret assembly.

The finder is a simple “positive” type, giving a large full-field image for the 35mm. lens, and using an etched frame for the field of the 3-inch objective and the 6-inch telephoto. Two small levers move supplementary optics into place to give a magnified field for the telephoto lens fields. The field of the 10-inch lens is indicated simply by a central dot, as this lens will probably be used only for extreme distant shots, such as following an airplane, or the like.

In use, the camera is amazing. In the first place, it is incredibly much lighter than one expects since, with the exception of a few small, highly-stressed moving parts, necessarily built of steel, the entire camera is made of magnesium. Loaded and ready for action it weighs but 13 pounds — or 15 pounds when the 10-inch telephoto is in place.

Camera. Note ease with which it permits following

a moving object like an airplane at almost any angle.

In the hand, the camera balances perfectly. It seems as easy to follow action with it as with a rifle. For stationary shots, the gunstock mount and two-handed grip give incredible steadiness. Motor and movement are so smooth-running that the Cunningham is probably the smoothest-starting hand-camera this writer has ever seen. In addition, the pilot-pin registering movement provides for professional steadiness of the screened image.

The new camera owes its inspiration to suggestions made over a year ago to Cunningham by some of the top-ranking members of Commander John Ford’s Naval Field Photographic Unit, and has been developed with the benefits of the experience some of these cinematographers have gained in actual service cinematography. The RKO Studio patriotically permitted Cunningham, who heads their precision camera machine-shop, to design and build the first cameras in their plant.

The design, however, has been planned from the start for mass production, so that as and when the military authorities approve it, the cameras can be turned out in quantity in any larger plant accustomed to precision work. It is probable that since 16mm has taken root so strongly for military cinematography (a development which has taken place since engineering on this camera commenced) a 16mm. adaptation may well be made. It certainly should be.

Cunningham’s camera seems certain of a brilliant future as a strictly military instrument, but once the war is over, it should have an even greater future in peacetime cinematography. For when such things are again feasible, it should be unexcelled for newsreel, sports and expeditionary camerawork, as well as for innumerable uses in scientific and industrial cinematography.

Here's a brief video on the Cunningham, hosted by ASC Museum Curator Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK:

After the war, these cameras found their way into Hollywood, serving as handheld units. Below, a surplus Cunningham is employed in tandem with a dolly while shooting the college football drama Saturday’s Hero (1951). On the right is cinematographer Lee Garmes, ASC (wearing a pith helmet).