Wages of Sin: The Irishman

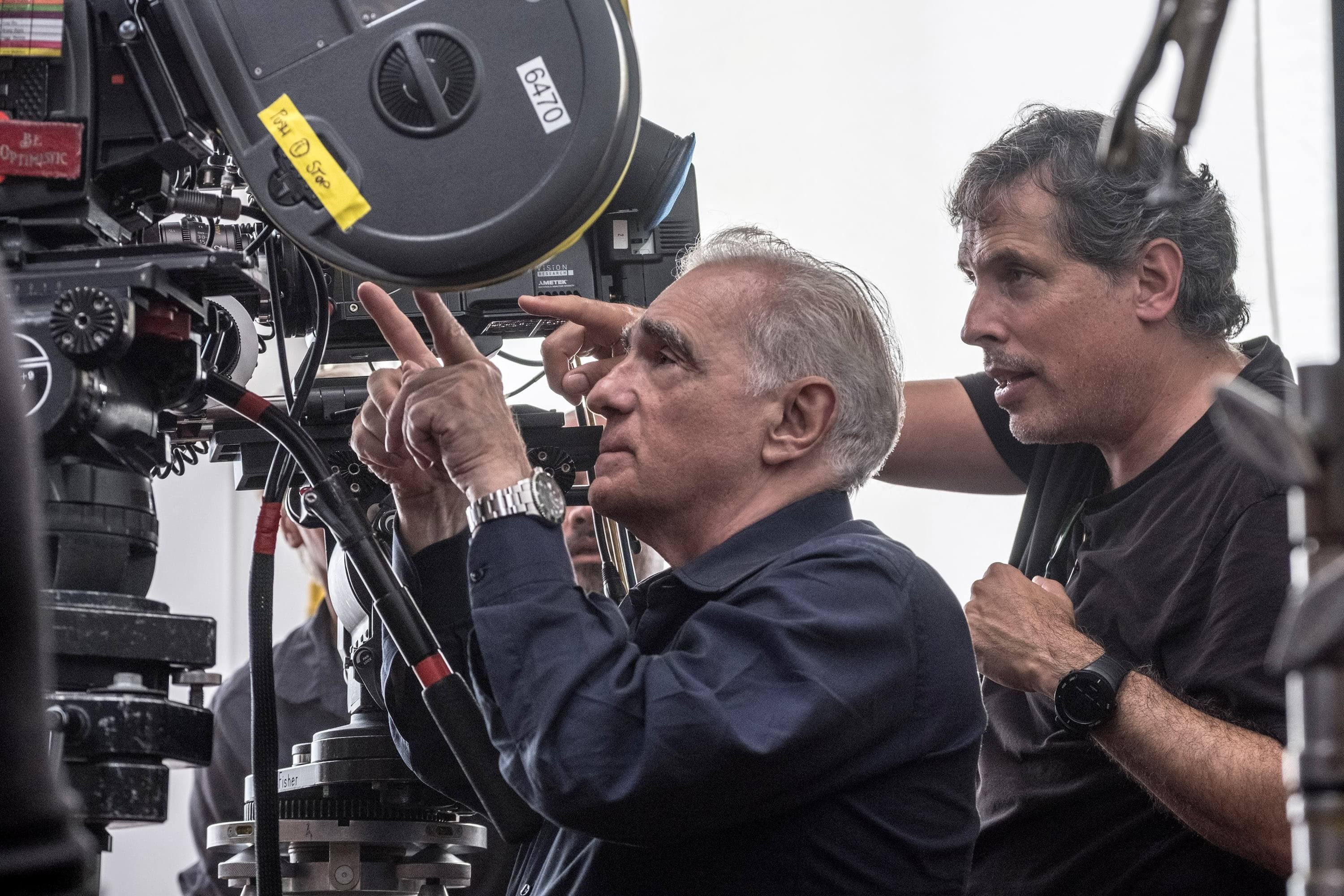

Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC frames a hit man through the decades for director Martin Scorsese’s epic crime drama.

Unit photography by Niko Tavernise. All images courtesy of Netflix.

The philosophies behind the production and presentation of Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman are steeped in contrasting ideas. Made with great attention to the traditions of cinema as captured on film stock, it also delivers its characters with the use of complex digital technology. The story unspools like a work made for the biggest of silver screens — and indeed, it has been presented in a highly anticipated and well-attended limited theatrical run — yet the feature will likely find the majority of its audience as a streaming production on Netflix, in homes and on portable devices of all sizes. And though forging into a marketplace increasingly depicted as having a short attention span, The Irishman confidently runs three hours and 30 minutes, and is built to be absorbed in one sitting.

For those with a deeper understanding of the moving image, there’s an enticing choice within the production’s creative DNA in Scorsese’s reteaming with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC to bring forth the saga’s visuals and emotions.

Prieto recalls a moment when he and Scorsese were wrapping up their work on Silence — which, through mud and inclement weather, was quite a challenge both creatively and literally (AC Jan. ’17) — and they paused to pose for a photo. “As we’re posing,” Prieto says, “Marty tells me, ‘I’ve been thinking about how to stylistically approach The Irishman. I think that maybe I’d like to try something that feels like a home movie, but I don’t want it to be grainy and handheld.’ That was an interesting challenge for me. What I understood was that he was trying to convey the memory of what home movies look like.” The need to present a story based on memories was something they both agreed upon for the long-gestating project.

For a time, the movie bore the tag I Heard You Paint Houses, the title of the Charles Brandt non-fiction book upon which the movie is based, about World War II veteran Frank Sheeran, who began as a Teamster union member and transitioned by degrees, from the 1950s through the ’70s, to become muscle and then assassin for the Philadelphia Mafia figures deeply enmeshed in the union — the hierarchy of which famously went all the way up to the fiery and once all-powerful boss Jimmy Hoffa.

With a cast that included Robert De Niro as Sheeran and Al Pacino as Hoffa — along with Joe Pesci, Ray Romano, Harvey Keitel, Bobby Cannavale and Anna Paquin — the stakes rose higher for Prieto, who was tasked with helping to establish a look equal to the story and its players.

The cinematographer knew from the script by esteemed screenwriter Steven Zaillian that the story would open with an aged Sheeran reminiscing as he plays back sequences from his often-violent past. What Prieto gleaned from Scorsese’s take was, “It feels like you’re remembering that era. So I thought, ‘What if instead of emulating the look of a home movie, we emulate the color characteristics of amateur still photography of the different eras? I started researching still-photography emulsions and the history of non-professional photography in the decades we would be representing, and ended up creating look-up tables that emulated Kodachrome for the ’50s and Ektachrome for the ’60s.”

For the ’70s and beyond, Prieto incorporated the look of the ENR silver-retention process that was invented at Technicolor Rome and first used by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC for Warren Beatty’s 1981 feature Reds. In that process, after the film has been bleached but before the silver is fixed out of the print, an added black-and-white development bath helps retain silver, resulting in sharper contrast and reduced color saturation.

“We did research into the characteristics of this process and created a LUT to use in two [of the film’s] phases,” Prieto notes. “For the first part of the ’70s, I used a ‘light ENR,’ making for just a little bit of desaturation and a little extra contrast. But then, right after Hoffa’s murder in 1975, the LUT shifts to a deeper version of ENR, so you’ll notice [during] the end of the movie that the color is further drained from the image. For me, this was a way to represent the loss of meaning in Sheeran’s life in the years after his friend’s death.”

Prepping these exacting hues was no quick process. “We had to do very complex color science,” the cinematographer says. “The early stages of creating the LUTs was done by Philippe Panzini from Codex in London. He is a fanatic about film emulsions; he has interviewed the Kodak scientists who created Kodachrome and Ektachrome, and carefully researched how these emulsions reproduce the different colors.”

This information was then given to color scientist and ASC associate member Matthew Tomlinson at Harbor Picture Co., where he worked with colorists Yvan Lucas and Elodie Ichter to perform the LUT-creation for the movie, “reproducing [the looks] for the digital and film [footage] and matching them,” Tomlinson says. Lucas and Ichter also worked with Prieto on the final color grade, which was performed with FilmLight’s Baselight system. (More on this below in "Evoking The Irishman’s Eras")

“I found that the digital camera that best reproduced the color characteristics of the LUTs on the film negative was the Red Helium,” Prieto says. “We mapped the LUT colors to match the film negative and the Red sensor. Industrial Light & Magic took care of matching the grain structure of the film negatives I used on all the visual-effects shots captured with the digital cameras.”

Once Scorsese had given his blessing to the looks, Prieto visited the Harbor Picture facility in Santa Monica with reference images. “I separated the decades through LUTs to help create an emotional arc for the character,” the cinematographer recalls, “starting with the ‘memory’ of Kodachrome, which is quite colorful, especially saturating the red hues — and then of Ektachrome, which is also colorful but deflects colors in a very different way, a little less saturated and more skewed towards cyan green in the shadows. And then, after Hoffa’s death, the color is gone from Sheeran’s life; this was achieved through the ENR LUT. I also push-processed the negative for this part of the story, adding additional grain to the image.”

Ultimately, Prieto reports, “We shot approximately 51 percent of the movie in 3-perf Super 35mm on Kodak [Vision3 250D] 5207 and [Vision3 500T] 5219, and the rest on digital cameras for the visual-effects work.” The film material was shot with Arricam ST and LT cameras and Cooke Panchro Classic lenses. The negative was processed at Kodak’s lab in New York and scanned at Technicolor in New York.

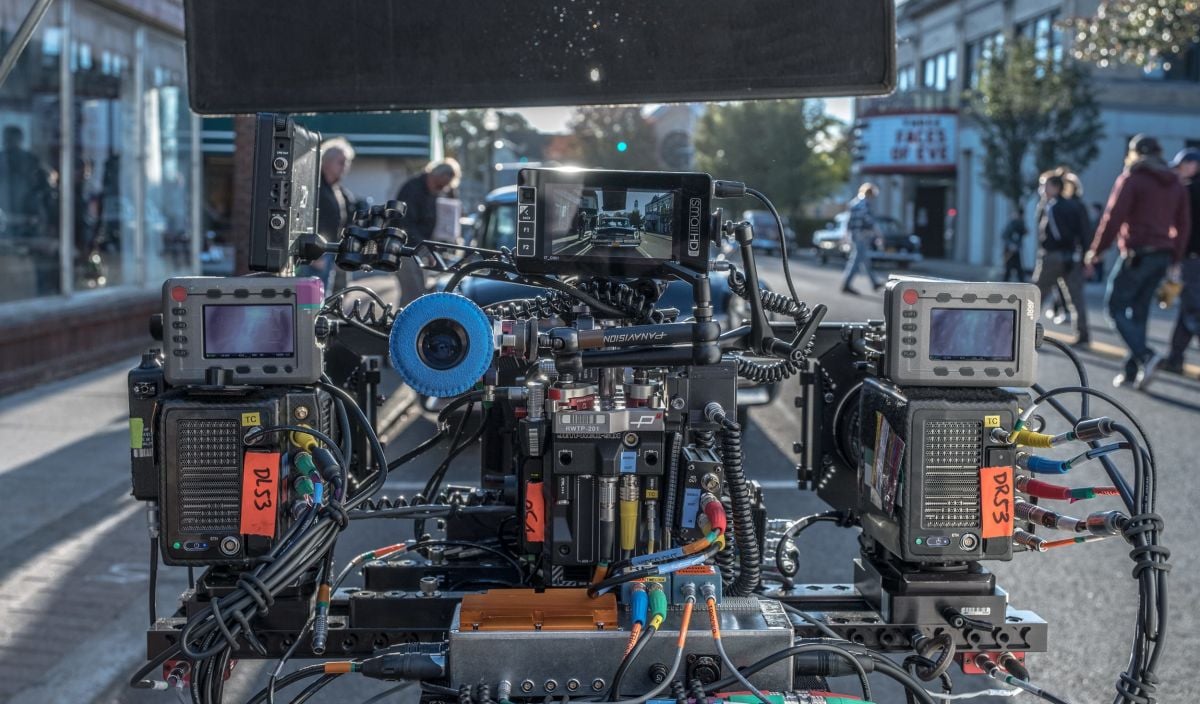

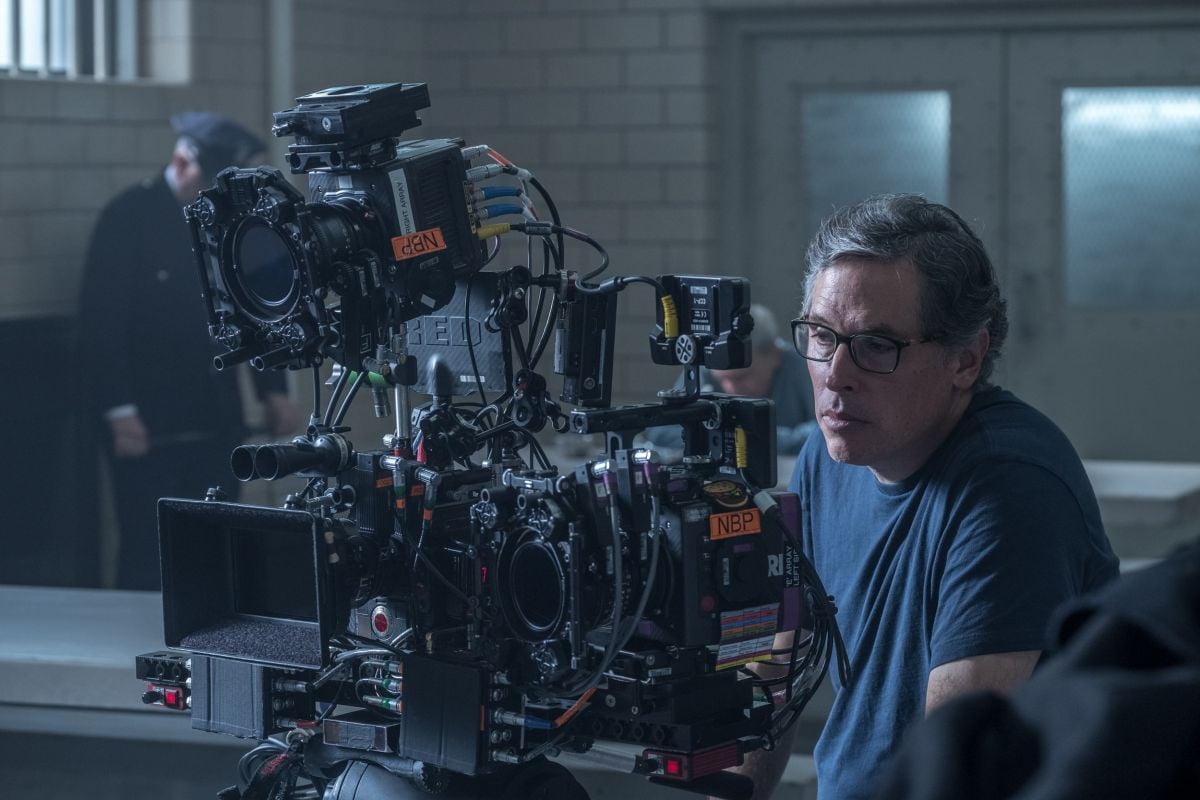

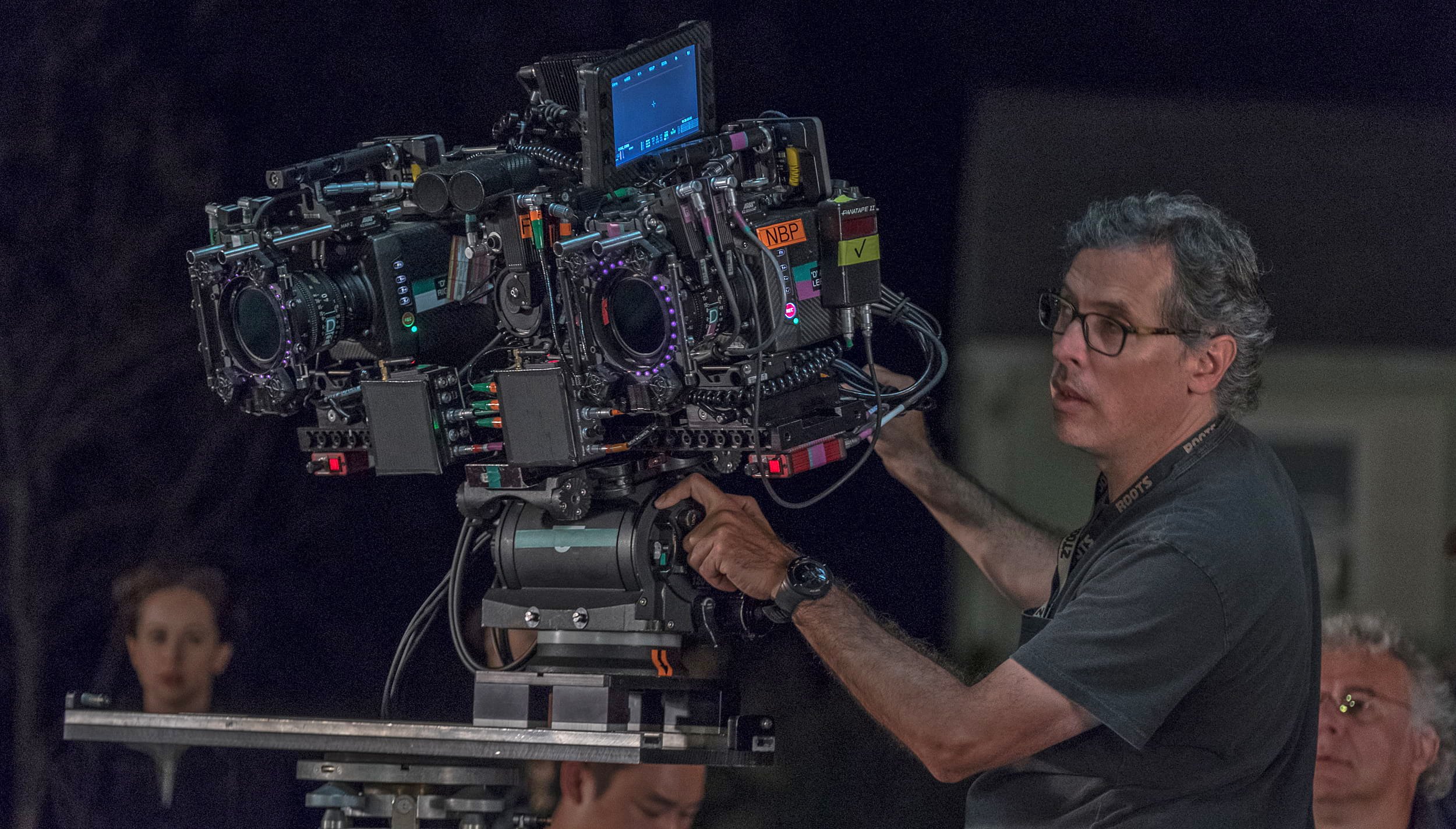

In order to depict De Niro-as-Sheeran through the several decades of the story, the production had to find a way to “de-age” him and other key members of the cast. The process — as overseen by ILM visual-effects supervisor Pablo Helman in close concert with Scorsese — was a tech adventure in its own right, but one thing the filmmakers knew from the outset was that their assembly of deeply naturalistic actors would not be game for the kind of production environment that has traditionally seen performers helmeted or covered in markers, and sometimes acting opposite props rather than their fellow thespians. ILM therefore worked closely with the filmmakers to develop a three-camera rig, with a main camera and two witness cameras, as well as a suite of software geared to handle the inherent complexities.

“The reason the VFX de-aging shots had to be captured digitally was that ILM needed three cameras with perfectly synchronized shutters for each angle,” Prieto explains. “This would not be feasible on film cameras, plus there were issues of size and weight. The two witness cameras, which were [Arri] Alexa Minis outfitted with [Arri/Zeiss] Ultra Prime lenses, were tasked with capturing every detail of the depth information of the faces for the VFX de-aging work. ILM needed the images from the witness cameras to be flatly lit, without any additional texture or loss of information caused by dramatic lighting. For that reason, these cameras were fitted with filters that cut out all the visible wavelengths while allowing only infrared light into the sensor. Around the lenses of these witness cameras, we had infrared-light-emitting LEDs that lit the actor’s faces with frontal infrared lighting. The Red Helium, which was usually outfitted with a Cooke Panchro Classic lens, could not ‘see’ this infrared light, so it captured only the actual lighting I created for the face.

“After each setup,” the cinematographer continues, “we photographed a mirror/18-percent-gray sphere and then shot HDRI stills and a lidar [3D laser scan]. ILM ran all that data through a computer program that analyzed the lighting captured by the lidar, combined it with the light intensity measured in the mirror sphere and the 18-percent-gray sphere, and spewed out a lighting setup that replicated the intensity, shape and color temperature of my lighting, as well as any influence from the light reflected from the set. This was then applied onto the computer-generated ‘young’ face of the actor to replace the face we filmed.

“All three cameras had to move in unison, so we created a rig that held them together and was light enough to be used on any camera head — Marty couldn’t be limited in the way he shot, so we had to make sure the rig could go anyplace he wanted and move in any way he envisioned,” Prieto adds. “We used carbon fiber for the plate, but the choice of the lightest motors, rods and accessories was important. Each lens had to focus independently of the others, so each had its own focus motors and all the cables to power them.

“Another characteristic the rig had to have was compactness,” he continues. “Sometimes the main camera had to be right next to a wall. For such cases, we designed the plate so we could remove the side support for one of the witness cameras, and we’d take the camera we removed from the side and mount it atop the main camera. The plate was designed so it would click into the fluid head, and we made special brackets that we’d mount to the plate when we put it on the Libra head for crane work.

“We called the rig ‘the three-headed monster,’ and Trevor Loomis, our incredible first AC, worked with Arri and ILM to create it,” Prieto notes. “Zoran Veselic was also involved in the first phase of the design.”

Given Scorsese’s own active eye — though the film’s narrative ethic was sooner stately than busy — there were also Steadicam shots (captured by P. Scott Sakamoto), and that system couldn’t accommodate the three-camera rig. “For Steadicam, we ended up using a two-camera version of the rig, and the third camera was positioned off the rig on a stand to capture the information of the face that the two cameras on the Steadicam were not seeing,” Prieto explains. “ILM required the triangulation of the three cameras for all the face-replacement shots.”

Crucial to the creative collaboration that brought The Irishman to fruition was Prieto’s work with a favorite colleague: gaffer Bill O’Leary. “Every time I do something in New York, I try to get Bill onboard,” the cinematographer says. “He had his work cut out for him because we had, I’ll estimate, about 300 sets. Every day we had company moves — or we’d be in, say, a hotel room onstage and then we’d move to Sheeran’s house — and a lot of sets had to be prepared, pre-lit and ready. Somehow, Bill makes it look simple. He’s kind of similar to Sheeran in the sense that he doesn’t talk much about how he’s going to do things or how it happens; he just executes a wildly complicated lighting scheme. Sometimes I worry he’ll say, ‘That’s impossible.’ But then it happens. He was a great partner.

“The other great partner in terms of lighting was our key grip, Tommy Prate,” Prieto continues. “Tommy also had his work cut out for him, especially the studio work, most of which was done in this huge, empty armory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Tommy created this giant grid with pipes, trusses and lighting rigs based on the floor plans of the sets. It was very time-consuming in prep to figure all this out and then to build the lighting rigs before the sets were even constructed. We had to pre-design our lighting from plans and miniatures. I found that thrilling — creating the light in the studio to make it seamless with the real locations.” (The story unfolds in Philadelphia, Detroit, New York, Miami and Washington, D.C., but the production used locations in and around New York City.)

All the hotel rooms were sets, plus both of Sheeran’s houses, as well as a room and restaurant in the Howard Johnson’s. “The Villa Di Roma is one of the main sets we built in a studio,” Prieto recalls. “We also built the interior of the house in Detroit where Hoffa is shot. The interior of Umberto’s Clam House, where Joey Gallo [Sebastian Maniscalco] is killed, was a set, too. There’s one nighttime establishing shot that starts on location outside a replica of Umberto’s, pushing in on a 50-foot Technocrane into a blue-screen on the door, and then transitioning into a continuation of the move on a Steadicam in the studio.”

All car interiors were shot in a studio. For the road journeys, the production deployed wall-size LED monitors that provided the cameras and the actors with a believable passing land- or cityscape. Prieto explains, “We worked with the OverDrive system at PRG with the support of [ASC associate] Dan Hammond. I had three walls made out of LED panels that measured about 10 feet high by 16 feet wide, plus two 6-by-6-foot panels. We used one of the big LED walls for the background of the shots — similar to rear-screen projection but with an LED wall instead — while the other LED screens were used for interactive lighting. The 2nd unit shot the plates we used for the LED screens with a system devised by Background Plates. It uses nine cameras to capture every angle around the car. On stage, we fed those images to our screens, which lit the actors in the car. That way we got all the accurate reflections on the car, on the faces and on the actors’ eyeglasses. I also used Source Four Lekos to create hard-edged sunlight effects.

“To light this film, we employed every trick of the trade: Fresnel, open-face and PAR tungsten, HMI, ellipsoidals, LEDs of all kinds, and, every once in a while, lighting balloons,” Prieto adds. One example of the latter is the scene at Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River, where Frank throws a gun into the water. “For that one, we used a Sourcemaker 8-by-8 Cube with the sides blacked out,” says O’Leary. “It was loaded with metal-halide lamps, the closest mercury-vapor equivalent.” The underwater shot of the gun floating down onto a pile of weapons was shot dry on stage with smoke and lit with two Rosco X24 X-Effects Projectors simulating the streetlight projecting water patterns on the bottom of the river. The gun floating down was created as a CGI element by ILM. Prieto notes that most of the night exteriors in The Irishman have a mercury-vapor coloration because yellow/orange-hued sodium-vapor streetlights didn’t exist at the time.

For the lighting in general, Prieto reports, “I emulated that mercury-vapor color with tungsten 10K, 5K and 2K Fresnels. We gelled them with [Lee 728] Steel Green — I use that gel a lot. It has a cyan color to it which looks to me very much like mercury vapor.” He notes that this technique was used for such setups as “outside Umberto’s Clam House, with many Fresnel units on rooftops, fire escapes and condor cranes. The exterior location was a corner on the Lower East Side. The interior was built in Astoria Studios and lit with Source Four Lekos shining through square holes in the ceiling, creating hot spots of white light in the restaurant.”

Perhaps no single setting offered as many opportunities and challenges as a banquet scene that found several of the key characters assembled for a signal event of October 1974, which was billed as “Frank Sheeran Appreciation Night” and celebrated at a storied destination called the Latin Casino, where Sinatra had done shows. The production shot this in a ballroom in Harlem.

Mindful of the significance of the color red in previous Scorsese movies — he particularly remembers a bloody scene in a car trunk in the woods from Goodfellas, as illuminated by brake lights — Prieto sought to push the metaphor by equipping the set with red light sources. “Bob Shaw, our production designer, was skeptical in the beginning because he was afraid it would not go well with the blue curtains of his initial design,” the cinematographer says, “but I shot a test with a lamp with a red shade and then augmented with red lighting to match that color, and Marty liked it. So Bob changed the curtains to gold and red, and we went in that direction (below). The concept was inspired by a banquet scene in the movie Network in which Owen Roizman [ASC] used red lampshades. To bathe the room in red light, I used Arri SkyPanels with Chimeras.

“All around the perimeter we put Birdies, miniature PAR cans, that we actually see in frame,” he continues. “This mix of golden highlights from the Birdies and the red ambient light from the lamps became the lighting strategy for those scenes. I also used two spotlights to light the speakers onstage and to roam around the dancers when the music plays.”

Prieto points to a sequence in the ballroom for which the spots were particularly useful: when Frank’s daughter Peggy (Paquin) dances with Hoffa. Peggy has seen her father have an intense conversation with quietly sinister mob boss Russell Bufalino (Pesci) and fully realizes what her dad’s deadly trade has done to their relationship, as well as to his (not-always-so-innocent) victims.

“Peggy realizes that these guys are thinking of killing Hoffa,” Prieto describes. “So I used the spotlight sort of wandering romantically through the dancers and the tables as an ‘excuse’ to highlight certain moments. At one point, while she dances with Hoffa, she looks across the room and the spotlight happens to pass right through her. The camera is on a dolly, circling them, and as she turns, it pans to find Bufalino and other men who are upset with Hoffa — just as the spotlight highlights that moment on them.”

Regarding the character of Peggy, Prieto notes, “From the subjective perspective of the way Marty films, she actually reflects all of Sheeran’s feelings and all that guilt he hides every time he sees her looking at him. It’s us seeing him actually judging himself.”

The cinematographer finds another telling moment in a scene with Sheeran as the sole passenger on a twin-engine small plane to be ferried to a gruesome task. As instructed by Bufalino, he has removed his sunglasses, and we study the brooding hit man from arm’s length as the plane throttles up. “When we shot that close-up inside the airplane,” Prieto recalls, “there’s nothing going on, just him sitting in a plane and the plane starts to go. But I was operating, and I remember looking through the camera. De Niro didn’t do anything. He didn’t move. He didn’t do an expression. But I remember immediately tearing up, feeling and seeing the depth of sorrow of this man as he realizes he is being forced to kill his friend.

“The way De Niro did that is just genius,” Prieto continues, “I have no clue how he was able to project all that without doing anything. It’s beautiful. There are so many moments like that in the film, seeing what these men do and not glorifying it at all. Marty is able to see them as human beings — human beings with struggles and issues and vulnerability. They’re not just these killers who are all-powerful. They’re scared, too.”

TECH SPECS

1.85:1

3-perf Super 35mm and Digital Capture

Arricam ST, LT; Red Helium; Arri Alexa Mini

Cooke Panchro Classic; Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime; Angénieux Optimo 24-290mm; Zeiss 28-80mm and 70-200mm Compact Zoom

Kodak Vision3 250D 5207, 500T 5219

Evoking The Irishman’s Eras

To provide, from the very beginning of production, the subtle visual cues that director Martin Scorsese desired for The Irishman’s various historical periods, Harbor Picture Co. and Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC undertook a much deeper process than is typical for the creation of LUTs and dailies — which yielded imagery from the outset that was very close to the movie’s final look. AC spoke with Harbor’s Matt Tomlinson, a color scientist and ASC associate, and colorists Yvan Lucas and Elodie Ichter, who also worked with Prieto on the final grade.

Matt Tomlinson: This kind of attention to detail [in the LUT-creation process], and the effort and time that was put into it, is something that’s not all that common. The Kodachrome and Ektachrome LUTs we developed with Rodrigo are part of the storytelling, and Rodrigo made decisions as to their specific time periods, and how these time periods should be represented by each look, by these color palettes. There were multiple sessions where we created LUTs using test footage from Rodrigo. He came in with images — books with photographic references and distinct ideas of what he wanted certain aspects of the movie to look like. He would point to elements of specific images that he liked. For each one, we would take the imagery that he shot and introduce that look. Then Rodrigo would say, ‘More of this, less of that,’ and it was created on the fly [as a collaboration between] us. It was really a surgical creation, where minor shifts were going on in different areas of the gray scale on the hue palette. The work was done very specifically, based on Yvan, Elodie and Rodrigo’s thought process in terms of what this movie should look like. There are actually about four LUTs total. Philippe Panzini of Codex was part of the creation process for the Kodachrome and Ektachrome looks; the ENR looks were based on work by Harbor; and the final creation was a combination of [all our efforts]. A Kodachrome look was used for the ’50s, Ektachrome for the ’60s, light ENR for the early ’70s, and heavier ENR after Hoffa’s death.

Yvan Lucas: Via the ENR process, there’s more contrast and less saturation. It’s a process we use in the lab. I was a color timer for 20 years before I moved to digital, and this is how we did it at that time for [films like] Seven and Delicatessen. When you see the print, the blacks look much deeper; you see details in the blacks and the faces, and the colors [in general] are desaturated.

Elodie Ichter: [Rodrigo] has a history of doing this kind of thing with us. There are a few DPs in the world who really want the dailies to be very close to the final look. [ASC members] Rodrigo, Chivo [Lubezki] or [Roger] Deakins, for example, really want to have the final look in the dailies — so it’s really important to work on that [for them].

Tomlinson: When we’re working on a movie, it’s our movie, too. We consider ourselves artists; we’re [craftspeople, and we] embrace that. [We put] our soul into it, and it really is about the collaboration and creating something that is unique. The Irishman is a great example. The film-derived footage was the hero for the show. After rigorous testing that matched the pipeline of how the film and digital material would be handled during the shoot and beyond, Harbor was able to create transforms so the digital would match the film.

Collaborator Spotlight:

Gaffer Bill O’Leary

American Cinematographer: When did you first become interested in filmmaking, and, ultimately, lighting?

Bill O’Leary: In college I took a still-photography class and a film-production class as a lark, and I really enjoyed them — so I ended up majoring in film.

Is there an early experience of learning the craft that can be related directly to what you do now?

Early in my career, in 1985, I met and worked with Roger Deakins [ASC, BSC] — who greatly influenced me — on Sid and Nancy. We had both worked in documentaries, so we had a common working methodology, and we both tend to be naturalists in [terms of] our lighting style.

The Irishman is your fourth project with Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC, following Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, The Wolf of Wall Street and the Vinyl pilot. Rodrigo thinks very highly of your work, and says you’re a great partner.

Kind words from Rodrigo. We spoke years ago about Brokeback Mountain, but it didn’t work out.

Did the logistical challenges of The Irishman — with its lengthy script, running time and visual-effects arrangements — make you hesitant to take the gig?

I’ve done jobs of comparable length, and certainly under arduous conditions, but these factors don’t usually influence my decision.

There are a lot of dark laughs in this film — a signature of Scorsese’s work — and one that paid off well was the tossing of Frank’s murder weapons into the river.

I think the idea of the gun-tossing was the repetition of it, and then the underwater payoff of dozens of guns. This ‘underwater’ shot was done on stage against a black backing, with two Rosco X24 X-Effects Projectors providing the rippling effect.

Rodrigo — a bit tongue-in-cheek — compared you to Sheeran in the sense that you prepare meticulously, take on the various challenges, and execute the tasks with a minimum of fuss and bother. Has this always been your working style?

I do believe in being well-prepped — it allows a certain freedom once one arrives on set. I also believe we sometimes overcomplicate the task at hand. There’s a James Wong Howe [ASC] quote where he speaks about how, over the years, he simplified his lighting. So yes, a minimum of fuss and bother, like Sheeran. Why use a .38 when a .22 will do?

Collaborator Spotlight:

1st AD David Webb

American Cinematographer: We understand that the shot-listing process on a Scorsese production is lengthier and more intensive than on almost any other show.

David Webb: A great part of the collaboration, which seems to me is unique to working with Marty, is that he, Rodrigo [Prieto, ASC, AMC] and I sit for three weeks, for four hours a day – we will start the process again soon in Oklahoma for Killers of the Flower Moon — and he goes through every scene, every line of the script, every word. Marty and Rodrigo come up with a shot list for the whole shoot. We call that the ‘annotated script.’ Marty basically outlines his vision and gives us the blueprint for how he wants to shoot the film. We do it on all his films, and it is one of Rodrigo’s and my favorite parts of the process. It is efficient because we are then able to transfer those ideas to all the departmental keys. Furthermore, during the shooting period, every night at wrap, we meet in the trailer — Marty, Rodrigo, [producer] Emma Koskoff and me. The four of us get out the script and art-department plans for the next day’s shoot and review the preconceived plan. Marty says, ‘Here are the shots. This is how we will start the day.’ This allows Rodrigo and me to arrive early in the morning and set up the shot. Marty’s sure-handedness and clarity of vision allow us to have a specific plan and enable us to attack the day with precise efficiency. There’s a stateliness and a moodiness to The Irishman that sets it apart, and helps ensure that the technical accomplishments of de-aging remain a means to an end, rather than a centerpiece. If you look at all of Marty’s films, each has its own mood. For a lot of Irishman, the technical aspect is solved by just living and breathing through the script, through what the story is, defining what the film looks like. He loves moving the camera, but there are also moments when he loves for the camera to just be kind of a collector of emotion.

How did you approach the large crowd scenes in The Irishman?

An AD’s job is to help execute the director’s vision, and that means making sure everything is organized and focused and that everyone is engaged, including the background performers. Marty has an incredible attention to detail and is very exacting. It has to be just right, and real, for him to be satisfied. For the Frank Sheeran Appreciation Night, we had a big crowd, including the dancers and the band, and we spent a lot of time casting the background and choreographing the various elements so that the feel was just right. I must say that the background casting in this film, the actual people [assembled], was the best I’ve seen in my career. The people [casting associate Jennifer] Sabel provided for all the Hoffa rallies, and especially the Tony Pro rally — it would’ve been impossible for us to not execute that scene with the people she provided — helped create an energy that was amazing. Marty was super-pleased that it all felt so authentic. That is of utmost importance to him: authenticity. Marty has an excellent research department, run by Marianne Bower, who I also worked with on Silence, and we all put a lot of effort into all the scenes. We also had a great team among my AD staff — Jeremy Marks, Trevor Tavares and Ryan Howard — and all the PAs, hair, makeup and, of course, the wardrobe department. Marty’s crew is full of dedicated filmmakers who love the process, and Marty demands excellence. He brings out the best in everybody because everyone is passionate about not only the material, but also his obviously important legacy. He arms you to be great, even though you literally go gray making his films. The process is incredibly demanding, and not just because of the demands he puts on you, because he [does] everything with positive energy, but because the crew collectively does not want to ‘mess up the master’s work!’ I will always be honored to be a part of it; it really is the greatest thing. Marty’s crew, after multiple films together, is very tight, and we are able to do what we do in a relaxed and efficient manner. Marty wouldn’t have it any other way.