The Lady From Shanghai: Field Day for the Camera

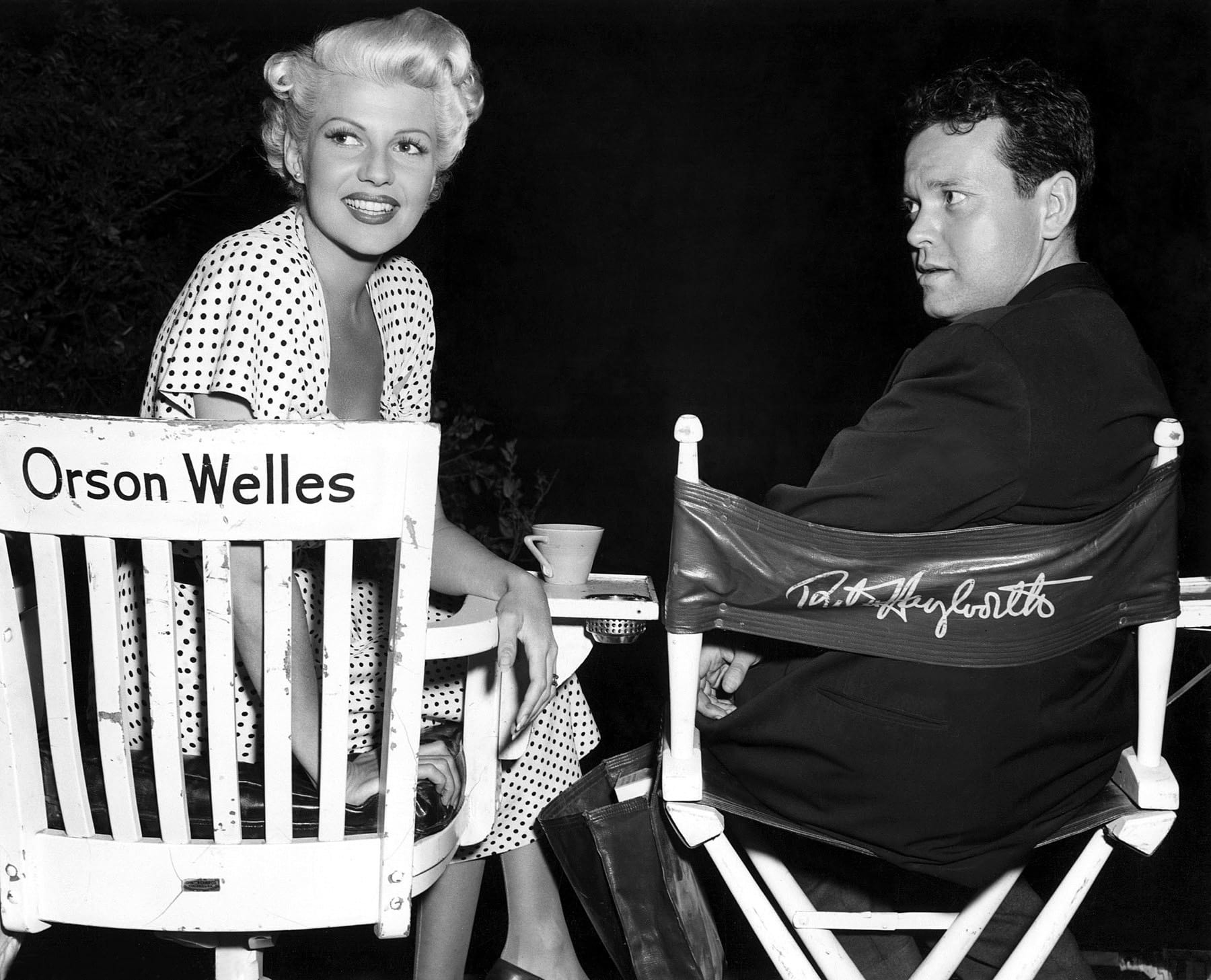

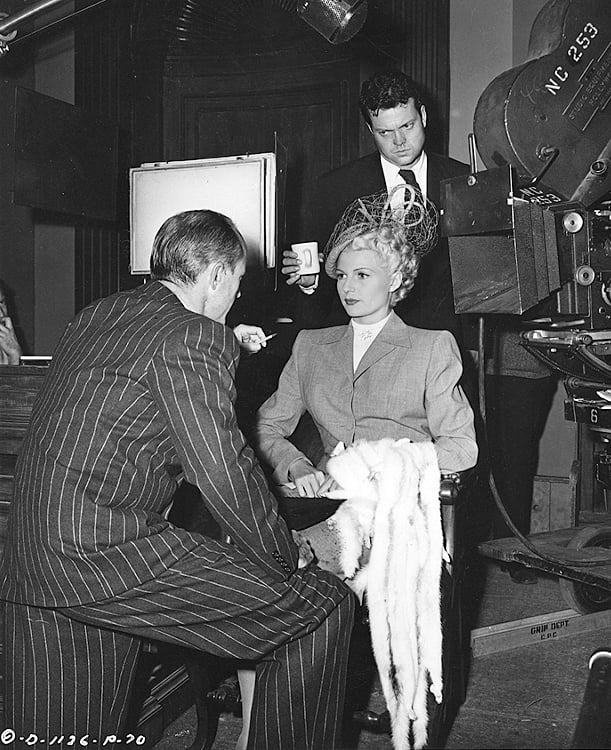

Rita Hayworth headlines this stylish Orson Welles murder-mystery, shot by Charles Lawton, Jr., ASC.

This article appears as it was published in AC August 1948. Some photos are additional or alternate.

One just naturally expects an Orson Welles picture to be different. Since he invaded Hollywood in a cloud of Martian terror several years ago, Welles has brought to the screen such off-the-beaten-track films as Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons and Journey Into Fear. Each of these has kicked over the traces in one way or another. Kane, especially, has been cited by serious students of the cinema as a revolutionary departure in film technique. While some of the stuffier critics branded the film as “consciously arty,” none could deny that it was, at least, different... a refreshing respite from the glossily stereotyped style so typical of our entertainment films.

Welles, perhaps more than any other director of the present decade, has brought a certain freshness to the screen. His originality is based on the premise that anything worth showing to an audience is worth showing dramatically. If he sometimes goes a bit overboard with the result that the creaking of the machinery can be heard, he is still to be complimented for endeavoring to inject a fresh perspective into the presentation of cinematic ideas.

His latest film, The Lady From Shanghai, is different. Technically speaking it is an excellent job. It misses being an important film only because, its plot is so cryptic that the motivations of the main characters become entangled to the point of obscuring the continuity. Even so, it is — because of Welles’ fine direction and the striking photography of Charles Lawton, Jr., ASC— a powerfully entertaining film.

Background For Murder

The plot of Lady From Shanghai is much too involved to permit summing up in a sentence or two. Suffice to say, it concerns a group of thoroughly disagreeable people (including the smoldering Rita Hayworth) who lure an unsuspecting, but good-natured seaman (played by Orson Welles) onto a pleasure yacht bound from New York to San Francisco. It is evident from the very beginning that there is homicidal hanky-panky afoot — but the real mystery (at least from the audience’s point-of-view) boils down to who wants to murder whom and for what reason. Everyone on the yacht hates everyone else, and each tries to lure the somewhat slow-witted seaman into doing the dirty work for him. The stakes in this murder derby appear to be a huge sum of insurance money, plus the undivided attention of Miss Hayworth.

With this network of conflict as a basis, the story begins in New York, goes aboard a yacht, stops at various Caribbean ports with a layover at Acapulco, Mexico, and ends up in San Francisco. It is in the City of the Golden Gate that Welles stages action against some of the weirdest locales ever seen on the screen. These settings include a dimly lit aquarium, the famous Mandarin Theatre in Chinatown, and the crazy house in a closed-for-the-season amusement park. If there is anything missing, it can only be the kitchen sink.

Although the audience may sprain its collective cerebellum trying to keep up with the vagaries of the plot, it cannot fail to be thrilled by the brilliant combination of action and photography which the picture boasts. Welles may confuse an audience but he is never guilty of boring one. In this case he has achieved some highly original effects, and has (as always) contributed heavily to the development of a fresh cinematic approach.

The Camera Creates Mood

Before Lady From Shanghai actually went before the cameras, it was decided to infuse the entire production with an ominous mood. Director of photography Charles Lawton discussed various approaches with Welles and decided to achieve his effect through a combination of low-key interior lighting, and natural light sources with comparatively few reflectors for exterior scenes. In this way, a smooth-flowing continuity was established between interior and exterior sequences. Transitions from outdoor to indoor sequence were executed without too severe a contrast in lighting largely because of the heavily filtered skies which dominate the exteriors. To gain this effect a combination of 23A and 56 filters was used. The use of natural light for exteriors, with its harshly contrasting shadow and highlight areas, allowed for some very dramatic modeling of facial features. In one sequence shot at Acapulco during which Welles and a sinister lawyer climb a hill so that they can discuss a phoney murder proposition, no reflectors at all were used. Welles was wearing a white linen suit which made his face look dark and somber—while the lawyer wore grey clothes which did not contrast so sharply with his skin and made his complexion appear white and sickly.

Closely complementing the dramatic interior and exterior lighting, are the dynamic compositions which cinematographer Lawton has applied so effectively. A distinct departure from conventional technique is the use of the wide-angle lens for extreme close-ups of people. The resulting distortion is directly in key with Welles’ desire for exaggeration in these shots. In many cases the exaggeration was enhanced by filming such close-ups from weirdly grotesque angles.

Perhaps the most striking sequence in the entire picture is that filmed in San Francisco’s Steinhart Aquarium. A masterpiece of mood, it is lighted solely by sources simulating the light from the display tanks. The players (Welles and Miss Hayworth) are thrown into silhouette against these tanks for the most part, and are effectively rim-lighted when the camera adopts another angle. What really inspires shivers, however, is the huge closeups of grotesque sea-creatures which form a background to the players as they deliver their staccato dialogue. By means of background projection the movements of conger eels, sharks and an octopus were precisely timed to match the thought provoked by the dialogue.

For example, when Miss Hayworth warned Welles that her husband was plotting a nefarious murder scheme, a huge shark glided behind her. When she spoke of the lawyer, a slimy eel dominated the background. Enlarging of these sea creatures through process photography lent impact to the symbolism.

Problems of Location Filming

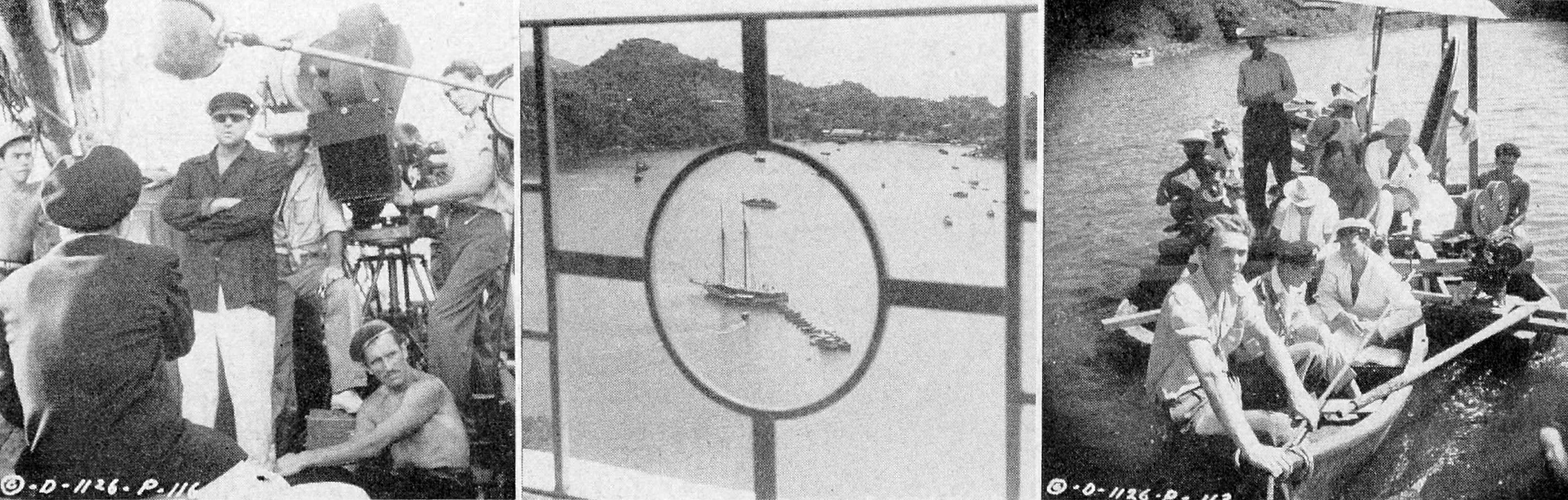

In order to shoot the location sequences for Lady From Shanghai, a company of 50 Hollywood actors and technicians flew to Acapulco, along with 60 Mexican extra players and technicians from Mexico City. More than 15 tons of equipment were shipped from Hollywood, one order of six tons comprising the largest single air express shipment ever undertaken by a movie location company.

For the boating scenes in tropical Mexico, Columbia Studios chartered Errol Flynn’s luxurious yacht, The Zaca, and Flynn himself served aboard as skipper. Scenes were filmed above and below decks, at anchorages in Acapulco Harbor, at Fort San Diego in Acapulco Bay, at Morro Rocks and other scenic spots, as well as at sea. A lavish new night club, Ciro’s, located atop the swank Casablanca Hotel in Acapulco, also served as a setting, as did the 25-mile stretch of white sand beach at Pied de la Cuesta.

The transportation of heavy sound and camera equipment through the tangled Mexican jungle was a major problem, but overcome by the sheer manpower of several hundred Mexican porters and canoemen. Sound trucks and generators were placed on native canoes lashed together to form barges, and then were floated through jungle-cluttered streams into shooting position.

Shooting aboard the yacht was, from the space standpoint very difficult, and these scenes, as they appear in the picture, are necessarily cramped in composition — but this actually works in favor of the overall effect because it produces an authentic atmosphere of crowded life aboard a small yacht. During filming aboard The Zaca, a long line of native dugout canoes anchored astern formed a bridge from the barge holding the generator so that electrical cables could be stretched for the camera and sound equipment.

In filming sequences at sea, the camera crew discovered that they could not depend upon their usual light meter readings. Reflections from the surface of the water kicked up more intensity than the meter recorded, causing over-exposure of the scene. This effect was noted in the screening of the first rushes, and a series of experimental tests was made to arrive at some sort of rule-of-thumb that could be used to compensate for the additional amount of light.

Back to Hollywood

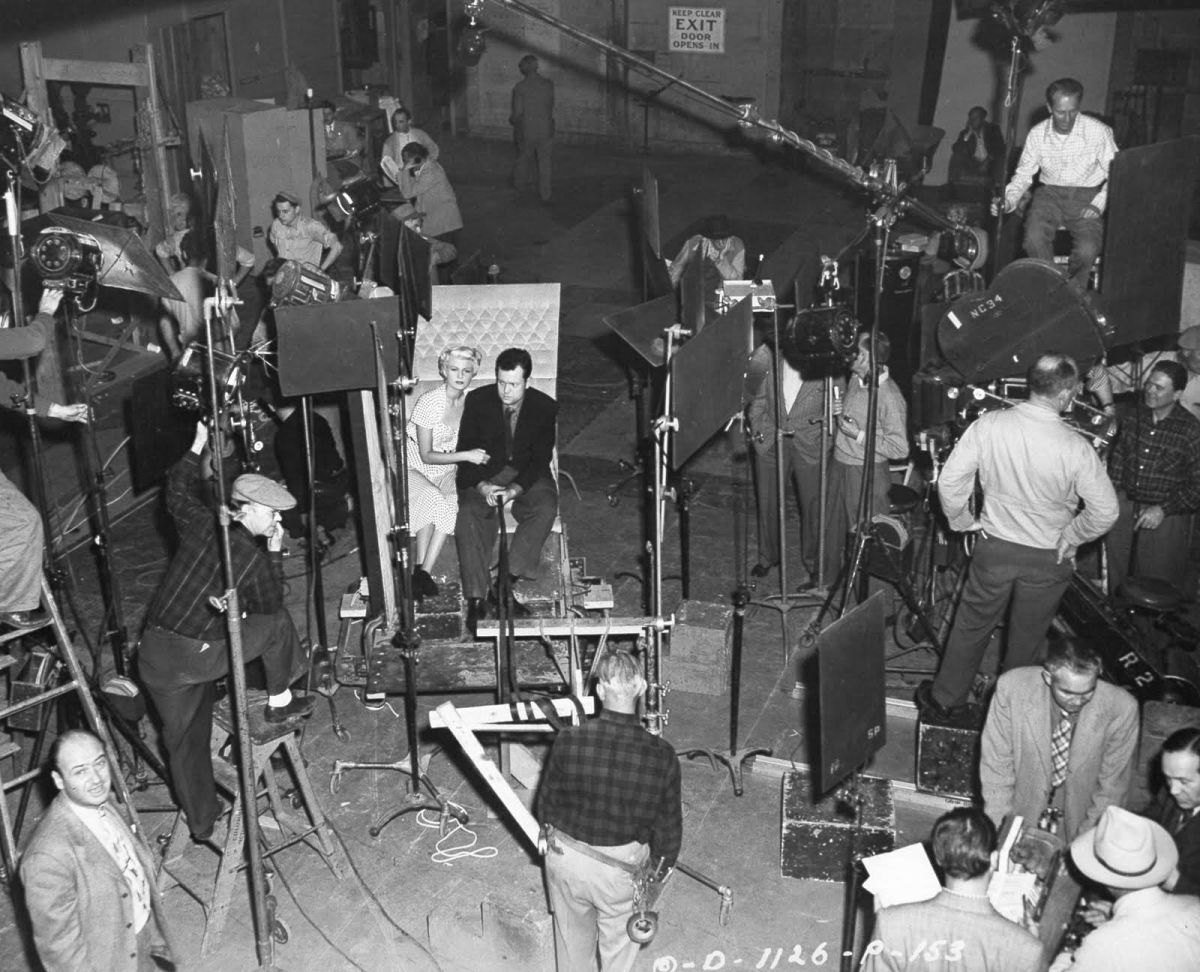

Sequences shot at the studio presented almost as many problems as those filmed on location. Welles, always ready to break precedent, rung up a new record for the longest dolly shot ever filmed. With his camera mounted on a 22-foot crane, Cinematographer Lawton kept his lens trained on Miss Hayworth and Welles as they rode for nearly three quarters of a mile in a horse-drawn open Victoria. Several huge arc lights, a sound boom and the camera crane rolled the full length of the shot next to the Victoria.

Stages 8 and 9 at Columbia Studios — which adjoin and can be opened up to form one huge sound stage—were transformed into the eerie "fun house” set which serves as locale for the picture’s final sequence. Studio workmen constructed sliding doors, distortion mirrors, and a giant slide 125 feet long which began at the roof of the stage and ended in a pit 80 feet long, 40 feet wide and 20 feet deep at the far end of the stage. Halfway down was a 30-foot-high dragon’s head with moving jaws forming a gaping mouth through which the slide passed, and at the foot of the slide two huge turntables, each 35 feet in diameter and specially geared to turn in opposite directions were built.

As might be expected, these gadgets allowed for some very unusual photographic effects. For one shot, Lawton and his operator, Irving Klein, had to slide on their stomachs down the 125-foot zig-zag chute. The camera was mounted on a specially constructed mat which was built to fit the curved contours of the chute. Then, as Welles took a slide, Lawton and Klein, lying flat on the mat, slid ahead of him filming his speedy progress down the whole length of the slide.

A set representing a maze of mirrors and containing 2,912 square feet of reflecting surface was also constructed. Eighty plate glass mirrors, each 7x4 feet, formed the basis of this unusual set, and 24 distortion mirrors of similar dimension were interspersed for camera effect. Several of the straight mirrors were of the transparent "two-way” variety which permitted cameramen to shoot action through them from the non-reflecting side. The climax of the picture, during which the antagonists shoot it out in this mirrored room, is one of those unforgettable cinematic moments that seem to occur all too rarely these days. The multiple images and the crashing of glass are directly symbolic of the brittle, many-sided personalities of the characters themselves.

The Lady From Shanghai is a puzzling but thrilling picture to watch. Director-producer-writer-star Welles has given it the loving care which is characteristic of his screen endeavors.

Cinematographer Charles Lawton has achieved some extraordinary effects with his uninhibited camera. But the real importance of the picture is its originality, its departure from stereotyped techniques — a healthy sign for an industry that continues to grow.

Lawton's other credits include Brewster's Millions, Blondie Knows Best, The Black Arrow, Mr. Soft Touch, The Long Gray Line and 3:10 to Yuma.

Camera assistant Richard H. Kline would later become an Oscar-nominated cinematographer and an ASC member, honored with the Society's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.