Future of Cinematography: The Next 100 Years

ASC members offer their perspectives on what the future holds in store for the art and craft of cinematography.

ASC members offer their perspectives on what the next century has in store for the art and craft of cinematography.

By Jon D. Witmer and Andrew Fish

By definition, cinematographers are forward thinkers, foreseeing a production’s visuals in intricate detail long before looking through the camera’s eyepiece — or at a monitor — on set. And in staying atop their craft, they also must keep pace with, anticipate and even drive technical advancements that impact how motion pictures are both made and experienced.

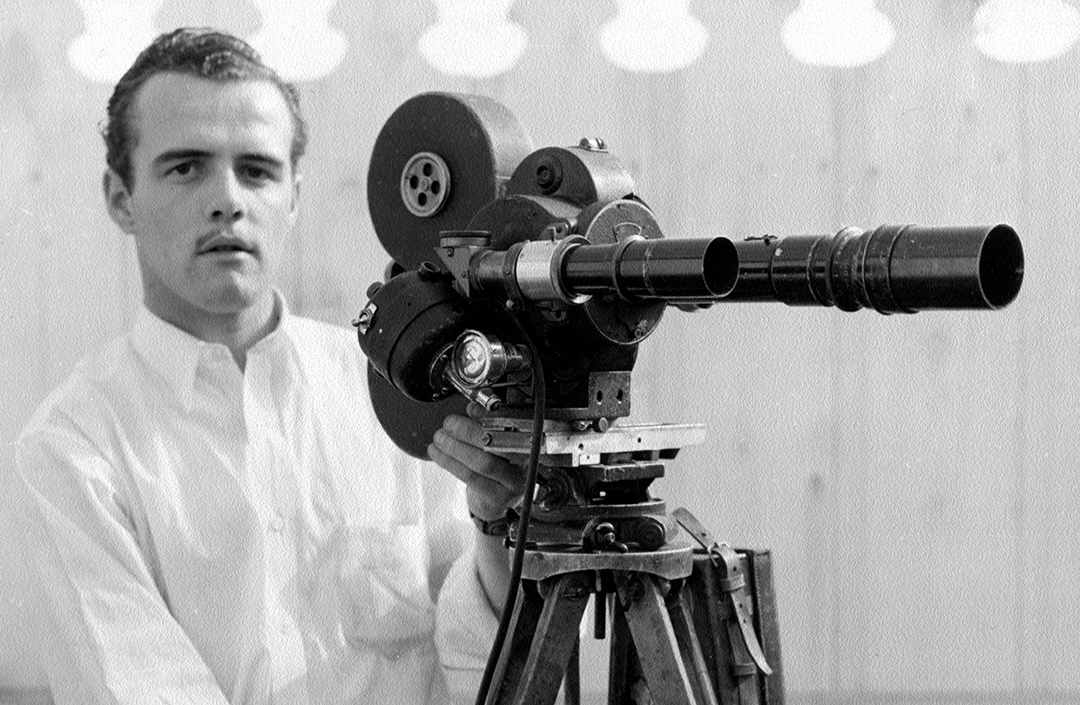

Throughout its 100-year history, the ASC has been home to perhaps the most forward-thinking cinematographers of all. Take, for example, Society member Leon Shamroy. In AC’s October 1947 issue, Shamroy offered a profoundly prescient prediction of cinematography’s modern tools of the trade. He wrote:

Not too far off is the ‘electronic camera.’ A compact, lightweight box no larger than a Kodak Brownie, it will contain a highly sensitive pickup tube, 100 times faster than present-day film stocks. A single lens system will adjust to any focal length by the operator merely turning a knob. … Cranes and dollies weighing tons will be replaced by lightweight perambulators. The camera will be linked to the film recorder by coaxial cable or radio. The actual recording of the scene on film will take place at a remote station, under ideal conditions. … Electronic monitor screens connected into the system will make it possible to view the scene as it is being recorded. Control of contrast and color will be possible before development.

Never content to rest on yesterday’s forecasts being proven true today, the ASC membership continues to keep its collective eyes on tomorrow’s horizons, even as the Society celebrates its centennial. “You can mark 100 years by looking back, but it’s also a time to look forward,” says ASC President Kees van Oostrum. “What is the future?”

Below, 23 of today’s active ASC members — and one distinguished associate member — share their visions of what’s to come in the Society’s second century.

ASC MASTER CLASSFor more, read this month's 100th Anniversary issue or subscribe now to American CinematographerSubscribe Now Read Digital Edition |

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC: Although cinematography is in constant technical development, I still believe that what we do as cinematographers has not and will not change. I continue to light based on my instinctive interpretation of what is put in front of me on any given day. Although I might be looking at a monitor rather than an actual set, I still use my eye to make judgment calls regarding lighting. The artistic approach has remained the same.

Steven Fierberg, ASC: I think that the role of the cinematographer is going to change less than some people might think it will. What we do now is not that different from what people did 50 years ago, and I think that 50 years from now, there will still be people doing exactly the same thing we’re doing.

Polly Morgan, ASC, BSC: Despite the evolution of how we tell the story and how it is shared, I don’t feel the true heart of cinematography will shift. And that is to use light, movement and framing to incite emotion and empathy.

Christopher Chomyn, ASC: While some may be distracted and preoccupied with gimmicks and gadgets, those at the top of their game will always point their camera at the story. The best cinematographers will collaborate to find creative solutions to involve their audiences in the stories they tell. As technologies change, masters of the craft will adapt, and use their tools — both the new and the more traditional.

James Neihouse, ASC: The democratization of filmmaking that the digital age has brought allows greater access to cinematic storytelling than ever before. Today almost anyone can shoot a movie; these burgeoning filmmakers are able to tell their stories with greater ease and at a lower cost than ever before. I believe the future of filmmaking has to be more about educating, mentoring and supporting these filmmakers than about any technology that could possibly come along. Passing on the craft, encouraging the art, while embracing new technology — all in the service of the story — will ensure that cinematography as an art form will continue well into the future.

Steven Poster, ASC: I think there is a mindset wherein everybody now feels that they’re a cinematographer. You can take your iPhone and make credible images with it. But the one thing that’s going to separate the pros from everyone else is the fact that the ability to tell stories with moving images will not get any easier. That quality of the cinematographer to accomplish a cohesive and unique view of the world will still be left to the ‘mighty few,’ as it were.

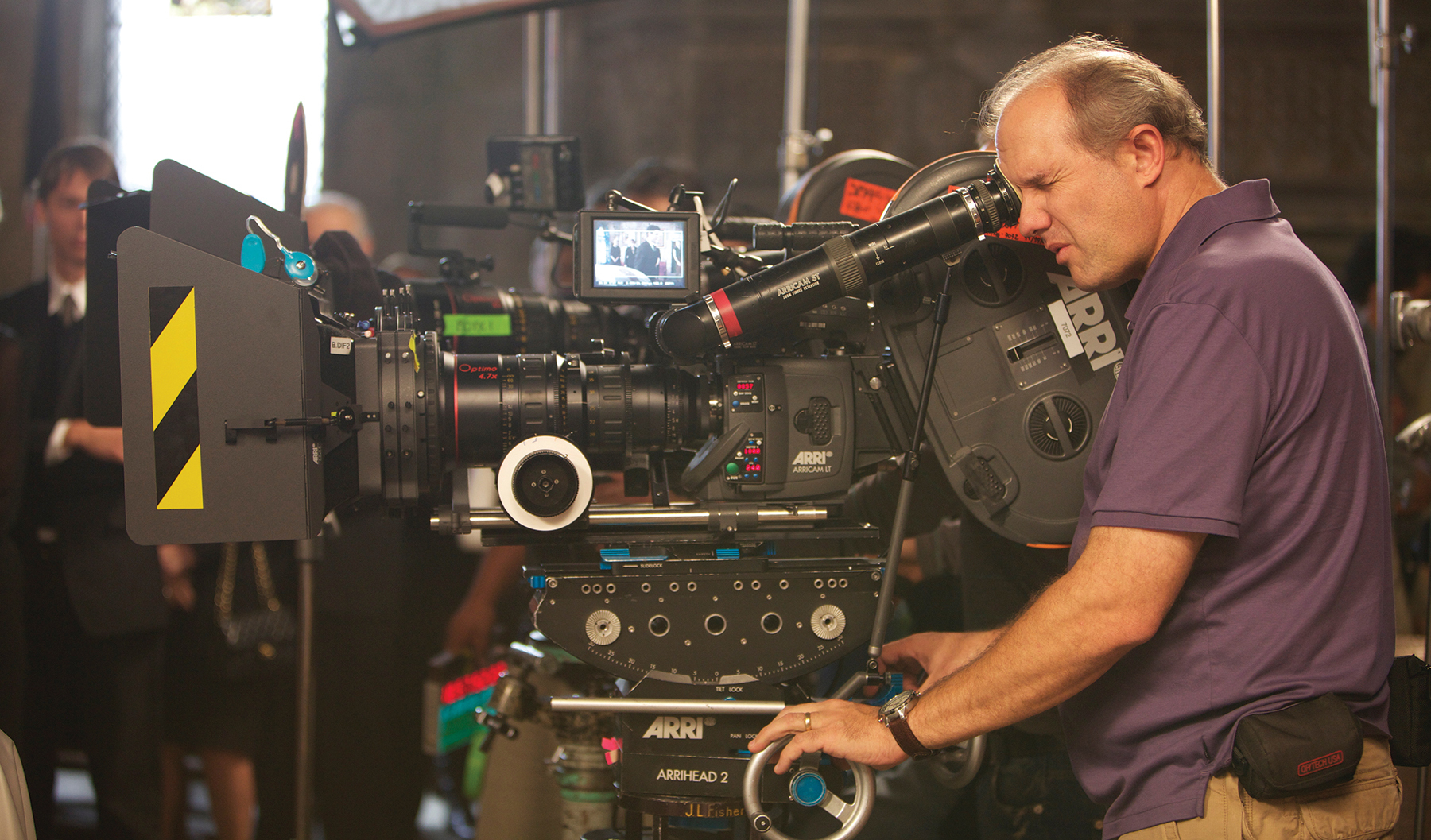

Tobias Schliessler, ASC: Today there are more people helping to create an image than when I first started out, especially when it comes to visual effects. But that isn’t a drawback to me. I see filmmaking as a collaborative art form, and having more options and tools at my disposal can reap great benefits. I love being able to get a shot that I perhaps couldn’t have done last year, or help to create a world with CGI that at one point we could only have dreamed of. Recent breakthroughs in technology have also opened up space for more creative voices. I can be equally inspired by a video shot on a small camera by an up-and-coming cinematographer as I can by a big studio movie. I don’t see this slowing down in the future, and I am grateful for that.

Morgan: Over the next century, I think the craft will continue to blossom as a wider scope of voices get the opportunity to exercise their art and vision in service to the story. I imagine that technology will continue to evolve, diversifying our art onto new platforms with exciting new tools.

David Stump, ASC: When I hear somebody say, ‘This technology isn’t viable,’ what I really hear is that they’re saying, ‘I don’t see how this technology is viable in my own hands.’ And that doesn’t mean there isn’t a kid in college somewhere who grew up on this and will adapt it into something that you couldn’t have imagined. When there comes a generation for whom there has always been VR, it’s going to be something that’s already in their vocabulary, something that they already have language for, and it will be much easier for them to start using it fluently and surprising us with the content that they generate.

Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF: Everyone is getting access to play with more tools and paint with more brushes — and with more time, because things are getting faster and more efficient. And I think that’s great! If a lot of great technicians and artists are able to express their art with more resources, then of course it’s going to translate into better and better cinematography. It’s already happening. Twenty or 30 years ago, [there may have been] 10 cinematographers you would admire as your role models, who were doing films that you thought were masterpieces. Today [there might be] 50 or 100 people doing amazing stuff. I don’t think it’s because we didn’t have as many talented people in the world back then — it’s that now more people have access to the resources to do great work. That’s awesome. More people are going to be doing great things.

Kees van Oostrum, ASC: Technology in the digital world has finally turned a corner where it’s not so much about, ‘Look at this, look at what we can do.’ It’s much more, ‘This is the intention, and look how we can keep that intention alive until the very end.’ Already this year, that’s more of the discussion than ever before. Before it was like a weight-lifting contest — ‘Which is 2K? Which is 4K?’ — and it didn’t necessarily relate to what we want to see as cinematographers. We care about what the image conveys emotionally, where we’re going artistically with it.

Poster: For years it’s been the ‘K wars’ — where everything was about resolution — and I think the next step is going to be about color depth. We’re already seeing the beginning of that. [Increased] color depth is going to give us more ability to control the image on a fine level. From 8-bit or 10-bit, you make the leap to 12- or 14-bit, or even 16-bit, and you start to see subtleties in colors and roll-off of color that enhances skin tone, for instance. And it’s going to give us more and more of that as we go. I think we’re also going to see, maybe in the next couple of years, an increase in using AI for processes of image capture. For instance, we will see the greenscreen become a thing of the past, because AI will be able to isolate a foreground character. There are already systems out there that are attempting to do that.

Bill Bennett, ASC: As computer processing power increases, more of that capability will be integrated into cinema cameras, doing what might be called computational imaging, where multiple lenses and sensors will be used to gather the image data. A view of the scene will be created from that data, where focus, depth of field, angle of view, are all changeable in postproduction. Light-field camera research is the beginning of that technology. Even the current smartphones can create a synthetic shallow depth of field with the use of two sensors and lenses, utilizing computational photography.

Lawrence Sher, ASC: The idea of light-field technology, of capturing imagery in such a wide range and then, later, in the postproduction process, actually repainting the light, exposure, focus, all those things — I think that will change the face of cinematography. What exactly that will mean, though, is really hard to say. It could be destructive; it’s certainly daunting and even scary. But it’s also exciting and freeing, creatively. Capturing imagery and combining it with virtual sets, with both practical and virtual lighting, and a combination of animation, visual effects and live-action photography to create unbelievably photo-real and authentic filmmaking is truly amazing.

Robert Primes, ASC: Just as there’s been a long overlap between the deep love we have for the beauty of film and the technical superiority of digital, I cannot help but feel we can anticipate an even longer overlap between our beloved tradition of photographing live scenes and the inevitable economies and efficiencies of computer-created or computer-enhanced subjects and images. Today our digital lighting and image-manipulation tools are so powerful that it is essential for cinematographers to master them if they are to stay relevant. That’s a harbinger of how the art and science of cinematography will need to adapt to even more disruptive technologies.

Stump: A big piece of the future will be cinematographers owning the hybridization of image generation. In the last few years I’ve started to use LED display panels in various sizes and configurations, both for lighting and to present images to be photographed. But the thing that I think nobody sees coming is mapping game-engine footage to panels of all sizes and shapes to create environments that you just couldn’t create any other way except CG, as a post exercise. In order for a technology like this to mature, we’re going to have to bring compositing, and adjusting the nuance of compositing, onto set. And that means putting it in the hands of the cinematographer, and the camera and lighting crew as well. Cinematographers need to be ready to manage that onstage. The ones who are ready to own it are the ones who are going to do great work with it. It’s just newer tech, and it gives you greater possibilities for the places that you can take us with your images.

Neihouse: As motion-picture technology gets more sophisticated, it creates all sorts of artistic possibilities, and as cinematographers we have to learn how to incorporate these advances into our craft without letting the technology drive the image or the story. We must strive to protect the art and craft of cinematography from being overrun by the ‘flavor of the day’ widget.

Rachel Morrison, ASC: I am very optimistic that the future of cinematography will be more inclusive, and that a more diverse collective of people behind the lens will help inform a broader and more inclusive worldview in the stories we tell. I am less optimistic that the cinematographer will retain the control they once had. While beneficial in certain ways, I fear that the evolution of technology — from higher-resolution cameras, to the ability to choose focus in post, to the growing ease and affordability of VFX compositing — is also hugely detrimental to the cinematographer’s singular vision, and to the perception once held that DPs were wizard-artists and guardians of the image. I sincerely hope that I am wrong.

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC: The future of cinematography, like the future of cinema, is being rewritten by the moment. Technology is changing viewing methodologies. Our biggest challenge will be maintaining authorship. The digital age invites a cinematographer’s work to be altered as others see the project to completion.

Alexander Gruszynski, ASC: I think we are entering — or have entered — a very treacherous time. On the one hand, new technologies [offer so many] possibilities for visual storytelling, and that’s obviously incredible. But then there’s the issue of control. With digital, instead of creating images, you produce files that can be interpreted and manipulated any way you want, and any way you don’t want. All these possibilities of manipulating images in postproduction are where we cinematographers have to be very forceful in retaining control of the image. This is not an easy task, because — partly due to politics and design — there’s an idea that we belong [exclusively] on the set. The postproduction process is also lengthy and discombobulated, and we’re not necessarily available, and it’s also not really in our contract to be a part of postproduction, other than [participating in] color correction — which is another gray area, contractually speaking. It’s a minefield that we need to learn to navigate so we can retain our integrity and the control of the image, which is now much more complicated than in the past.

Sher: Cinematographers will need to start on the picture a lot earlier than they are currently. That’s how you’re going to create a movie that still has a cinematographer’s imprint, and the truth is, the movie needs the cinematographer’s imprint — not because we’re special beings in some magical way, but because our skill sets are unique, just like a production designer, just like any artist on a film. And without that key ingredient, we’ll see more and more movies that feel like they’re being first and foremost driven by previs. That’s something we should remedy sooner rather than later.

Guillermo Navarro, ASC: The challenge facing cinematography is the fight for ownership of the work. We’re the ones who know how to tell the story with images; we’re the ones in control of the film language. That is the most important tool for the cinematographer. My cry for the future generations of cinematographers is that you have to work and fight to protect the ownership of the film language. It’s not the camera that does the work for you, or the new chip, or the new light. It’s your ideas that have to be transformed into images that tell the story. No version of technology will take that away from us.

Michael Goi, ASC, ISC: The history of this industry is a history of visual storytelling, and it’s adapted itself to the introduction of sound, the introduction of color, the introduction of video. If you hitch your wagon to technology as the thing that’s going to save you, you will ultimately fail. Because it’s about telling stories. We as filmmakers need to have the biggest toolbox available to us of any medium in any form to be able to visually express ourselves. That could be film, that could be video, that could be digital, that could be a computer — whatever it is. The fact of the matter is that cinematographers and the associated crafts bring a certain point of view and a certain artistic aesthetic that is individual to us as creative people, regardless of whether we shoot on film or we shoot on toilet paper. It does not matter. You choose the medium that works for the subject that you’re trying to create.

Papamichael: Our job is to help the director express their vision of a story that is given to us in the form of a script. We still need to communicate with the director and find a common language. If we are not in sync there, it creates a problem regardless of the equipment we are dealing with. We have to constantly explore the scope and limits of our tools, but not neglect our artistic goals. As long as we can afford the freedom to collaborate with our artistic companions and choose projects that we love, we as cinematographers will have a long future.

Sandi Sissel, ASC, ACS: We will always be storytellers and painters of light. New technology is revolutionary, but the camera doesn’t tell the story. We do. The art form of cinematography will remain if we just nurture those coming in to take our places. I’ve spent a lot of time in film schools, and we are in good hands.

Primes: Because the political issues are likely more challenging than the technical ones, it is essential the ASC keep ahead of this to support new technologies rather than resist them. We should, of course, continue to preserve, celebrate and cherish the work and the masters of the past, but our very existence will be jeopardized if we don’t stay on the cutting edge of future image-making.

Gruszynski: I think that’s where the ASC needs to play a big role, in trying to steer this ship through the storm in such a way that we still can put our signature on [the work] as authors of the photography.

Richard Crudo, ASC: The cinematographer’s role remains exactly the same as it has been since the first turn of the crank on Edison’s prototype camera. And that’s because what we do is not about technology. It’s about the mindset, the vision and the hand that wields the tool. As long as we maintain that position, everything’s going to be great, regardless of how we actually create visual entertainment. Ours has always been a history of change. Cinematography has always contained within it an attitude of pushing forward and improving the technology. What’s the next big thing? How can we do what we do now better, more creatively, more efficiently? That’s never going to change, and that’s good. We should always embrace that. It’s exciting. It would be boring if it stayed the same. I hope I’m around for a really long time, because I want to see where it all ends up! Review the cinematography of every decade, and you’ll notice that every era had its look. Movies of the ’20s don’t look like movies of the ’50s; movies from the ’50s don’t look like movies from the ’60s — and nothing from the ’60s looks like anything today. It’s all constantly evolving, and cinematographers have always managed to be there to encourage that. We’ve also somehow managed to transition and find a way to make ourselves indispensible to the overall process of filmmaking. So, whatever direction the future takes us, as long as producers and directors realize that our expertise is absolutely necessary, then everything’s going to be fantastic. Our mentality and our temperament and our vision — that’s not going to change. That’s forever, and that’s what affects people. That’s what matters. And the effect of that is what lasts. Beyond that, nobody cares about the technology. Do you think the average viewer cares? They don’t. And they shouldn’t. Their only concern should be, ‘Does this touch me in some way?’

Garrett Brown (ASC associate member and inventor of the Steadicam): Cinematography in 100 years: Ben Franklin could hardly have explained his world to a neolithic hunter-gatherer, and explaining ours to Ben would be even tougher! So of course, 2119 lives, tools and practices are presently inconceivable. Nevertheless, here goes: 100 years hence, cinematographic artistry will still be prized, but our gear will be unrecognizable. Long beyond infinitely large ISOs and vanishingly small cameras (with computational bokeh), and long past ever-tinier drones silently blowing away our precious dollies, cranes and (shudder) Steadicams... all our gear will be biological: fingertip camera implants streaming to editing implants and CGI implants and onward to consumer implants. And gifted cinematographers will at last be giving the finger!

Mat Beck, ASC: The traditional definition of cinematography is expanding. Imagery is data, and we will see more and more data processing in the final image. Some high-end movies are using visual-effects techniques in virtually every frame, so the palette, the quiver of arrows, the toolbox — whatever metaphor you want to use — is continually growing at the high end. The question, ‘Can we get that shot?’ is more and more answered with a VFX response: ‘We can get it or make it. How much money, time and processing power do we have?’ The data gathering is growing in kind as well as amount. Higher res, higher frame rate, more camera and lens metadata, camera-tracking data, performance capture. Multiple cameras for panoramic VR background. Multiple lens data for computational photography. At the high end of film production, all this data and processing power will further the separation between the final image and the original critical moment on set — if there even is a set. With all these capabilities come more challenges — and more opportunities for noodling, procrastination, dissolution of creative control. In a world where most of the frame, or the scene, or the movie, has a virtual camera shooting a virtual avatar on a virtual set, the cinematographer is going to put his or her creative stamp on the picture outside the traditional arena — in the virtual one. And while these new technologies create challenges at the high end, as they trickle down it makes things easier for productions on the ‘low end.’ The future is already here if we have A-list directors shooting movies on the iPhone. To mangle Marx, the means of production — and postproduction and preproduction — are being more widely distributed among the proletariat. Looking forward, beyond more methods of distribution in the marketplace, there are going to be more ways to get the imagery inside people’s heads. In 100 years? We’re going to be dealing with direct neural inputs, for sure. I’m imagining interactive sessions tracking our neural response to the imagery. So besides being visually creative and technically good, a great DP is also going to have to continue to be nimble and curious as to what the latest thing is that’s coming down the pike. We can virtualize the set, the camera, even the actor, but we can’t yet virtualize the audience. All that digital stuff goes through an analog processor — the 31⁄2-pound lump of meat and fat between our ears — that continues to be the ultimate creator and arbiter of great imagery. People care about people. And the more technology facilitates, intrudes into, and messes up our lives, the more people are going to continually react to something that is human and organic — and in some ways atavistic. The technology will only ever be a tool, and never a solution, in my opinion. There are some people who think that in 100 years, eventually there is going to be a hybrid between computing power and us — some kind of cyborg, or whatever the term is. That’s entirely possible. And maybe that’s the evolutionary path that was always laid out for us and we just didn’t know it, that we were destined to invent machines smarter than us, and then crossbreed with them. I’m not clever enough to see how that’s going to turn out, but I think human emotion and human aesthetic is still going to be the determinant factor. It’s going to be the source and the arena of judgment for how good a movie is — even if it’s not a movie, and it’s not exactly us watching it.

Shane Hurlbut, ASC: I always think back to that song ‘The Future’s So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades.’ That’s how I feel about where cinematography is headed. It’s the synergy of innovators and trained artists inspiring everyone to truly believe that we can change. We will see new technology that can eliminate the old tools the film industry was built on. We need to learn from these large tools and reinvent new ways to shoot movies. When you watch an animated film, the camera has no limitations. There is no physical mass that the grip team has to move, there are no restrictions on the lensing or stabilization, and lighting is executed with ultimate control, so the characters look amazing. Size does matter to improve the filmmaking process. I would love to hold a large-format camera in my hands that weighs only 2.5 pounds. Remember in 2009? We had that camera [with DSLRs], but it was only 1080p and very quirky. It’s about speed, ease, and how you can fit into spaces. You don’t need to remove walls, which means more practical locations, spending less money, and giving the artist complete freedom. The tools that we use to compose, move and light will change the most. Lighting is already on the way to becoming more efficient and cost-effective; lights are smaller, lighter and more versatile, providing increased creative potential. In the motion department, we will see huge developments to strengthen our gimbal systems, to make them smaller and increase their accuracy. In the camera department, we still have large cameras with large accessories; these will shrink, so that the camera itself will not be much bigger than the sensor it holds, with a media card that is small and lightweight and can process 12K raw if necessary. As artists, we will continue to immerse our audiences in new ways and inspire creativity in the next generation of filmmakers. We always have to find new and exciting ways to push ourselves out of our comfort zone.

Jacek Laskus, ASC, PSC: The strength of the cinematographer is in understanding and guiding the story through the visual language, and understanding how both work together. This is beyond the job of a gaffer, camera operator, colorist or postproduction supervisor. I feel that the cinematographer should be the guiding visual force throughout the project — starting in the beginning, in preproduction — to understand what the story is, and why we’re shooting with certain cameras in a certain way, and why we’re covering certain scenes certain ways. As cinematographers, we influence and supervise this all the way to post, making sure that the visual tonality and the language is respected, and that it follows the conversations and decisions that were decided early on in preproduction. I find that a lot of young cinematographers are preoccupied with technology, and that the directors they’re working for are mostly afraid of technology. A lot of times the cinematographer will give the director all this technological information about shooting 4K, 6K, 8K, this camera vs. that camera — and then suddenly the director’s brain explodes, and they put their hands to their head and don’t want to hear any more. The conversation shouldn’t be about what lights you’ll use, what filters, what kind of processing. Who cares? Don’t bother them. They have to deal with storytelling, the actors, the writing, the schedule — all that stuff. They don’t need your tech information! I don’t think technology can save us. What can save us and our profession is building the relationship between the director and the cinematographer — the ability for the cinematographer and the director to form a creative bond so that the director can rely on the cinematographer as a friend and as a true visual collaborator who has the ability to see the images that support the story he or she wants to put on the screen. That is what will save cinematography. The cinematographer needs to be able to listen to the director and read the script the way the director would read it. What is the most important scene? Why did you decide to make this film? What is unique in this film for you? And how can I help you put that in visual terms so that my work is invisible but it’s helping the story? If you develop those strong relationships, then a director will say, ‘I need that cinematographer, I need that eye, I need that conversation.’ Because once you truly hear the director, then he or she is your friend. And that’s how you stay relevant.

Van Oostrum: The ASC’s role for the future is the same as it was in 1919. When this organization was formed, [its founders] were concerned about technology from the point of view of, ‘How do we apply it to our artistry, and how do we further our technical ability?’ You cannot be an artist if you don’t command the technology. You don’t have to do it all yourself, but you have to have a comprehension of what is possible. And they also knew in 1919 that education is an integral part of getting there. So it’s all the same discussion, just with different means and different technologies. There is a lot to discover and a lot to do. Our industry is only going to grow. So I see the future as being very bright, with lots of opportunities to do what we always wanted to do — and to continue doing what we have been for the last 100 years.

Navarro photo by Kerry Hayes. Neihouse photo by Claire Mondragon. Poster photo by Dale Robinette. Crudo photo by Douglas Kirkland. Brown photo courtesy of The Tiffen Co. Primes photo by Scott Shephard. Morrison photo by Dana Kinsky. Schliessler photo by Gregory E. Peters. Hurlbut photo by Melinda Sue Gordon, SMPSP. Additional photos courtesy of the ASC Archive.