The Photography of Patton

How the in-depth character study of a controversial general was made into a spectacular motion picture.

By George J. Mitchell

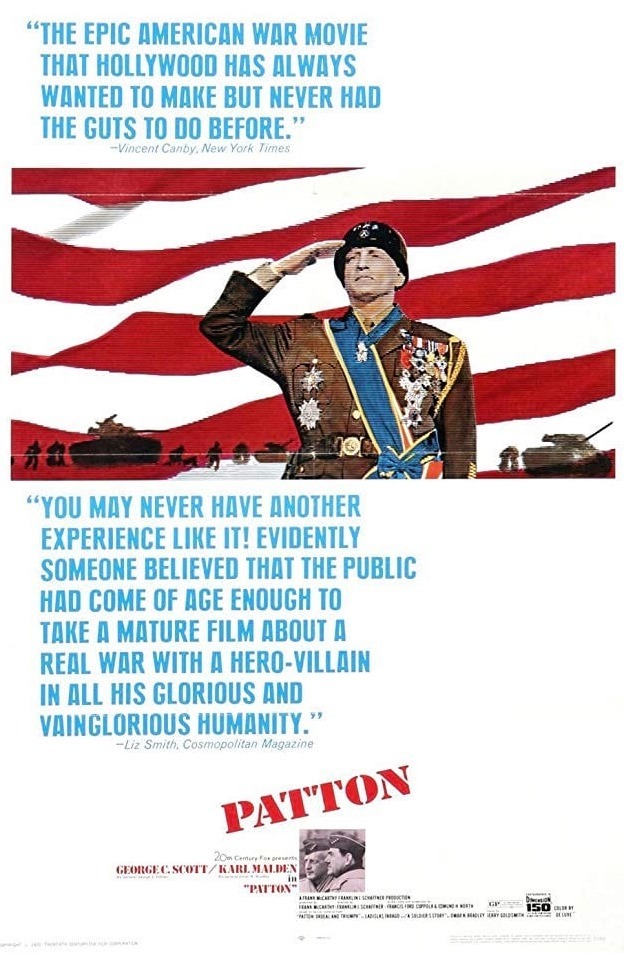

Patton is an in-depth screen portrait of the most controversial and successful commander of World War II. It is more than a war film. Rather, it is a strongly etched character study of a military maverick — a man who refused to run with the herd.

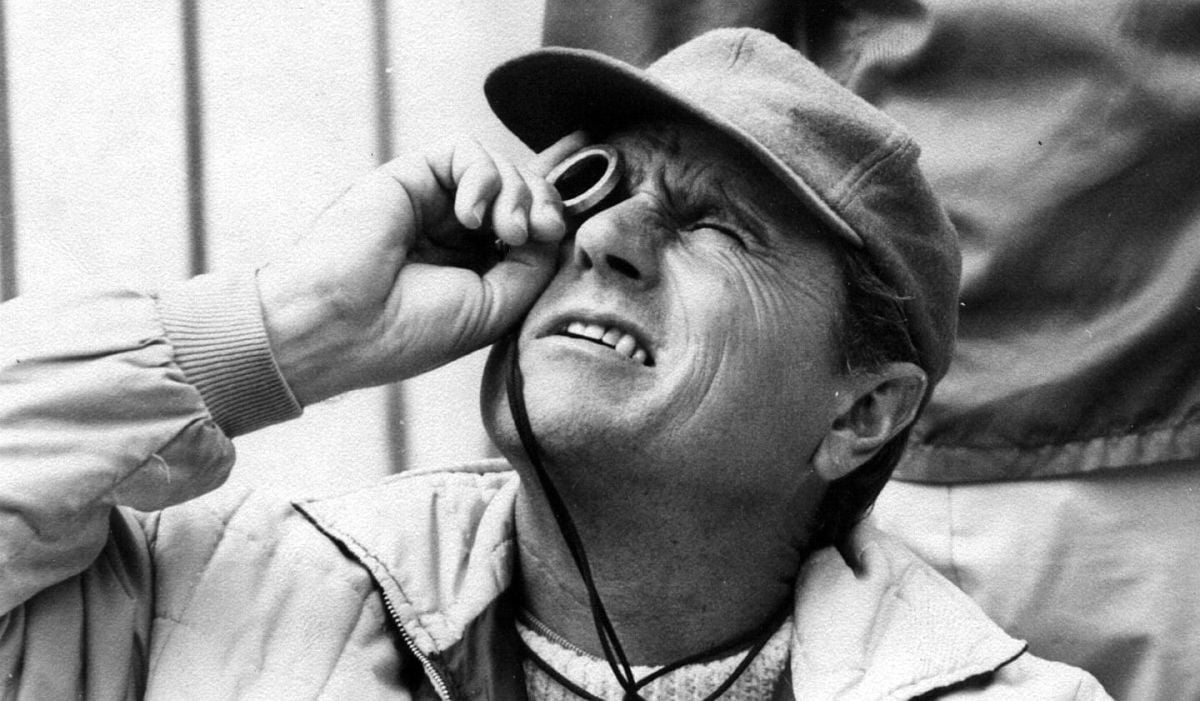

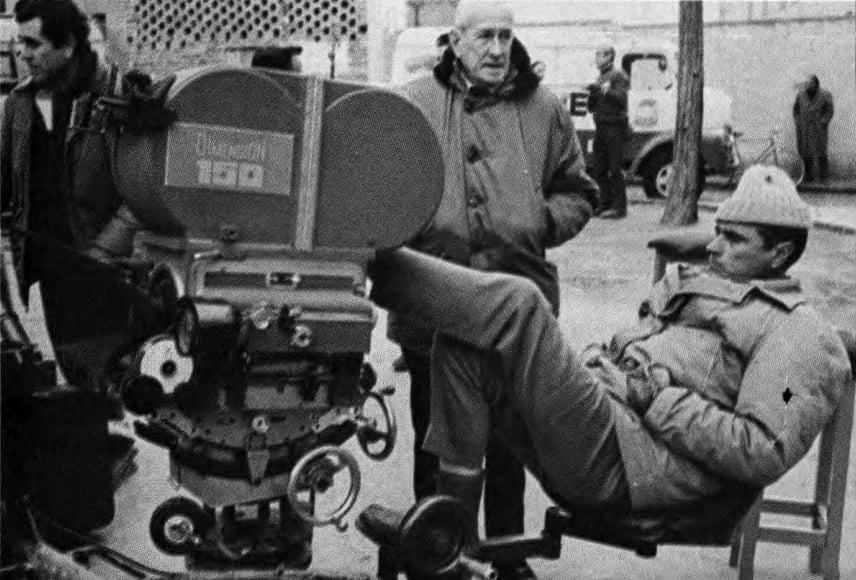

Filmed by 20th Century-Fox in Dimension-150 at a reported cost of $14,000,000, Patton is not only superior screen entertainment but is also an exceptionally well-made picture. This is due primarily to the talented people producer Frank McCarthy brought together for the production. For example, there is an unforgettable performance by George C. Scott as Patton; powerful and incisive direction by Franklin J. Schaffner; a non-angled, definitive screenplay by Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North; an inspiring music score by Jerry Goldsmith that makes use of an old Army fife and drum tune as the leitmotif; and superb photographic imagery by director of photography Fred J. Koenekamp, ASC.

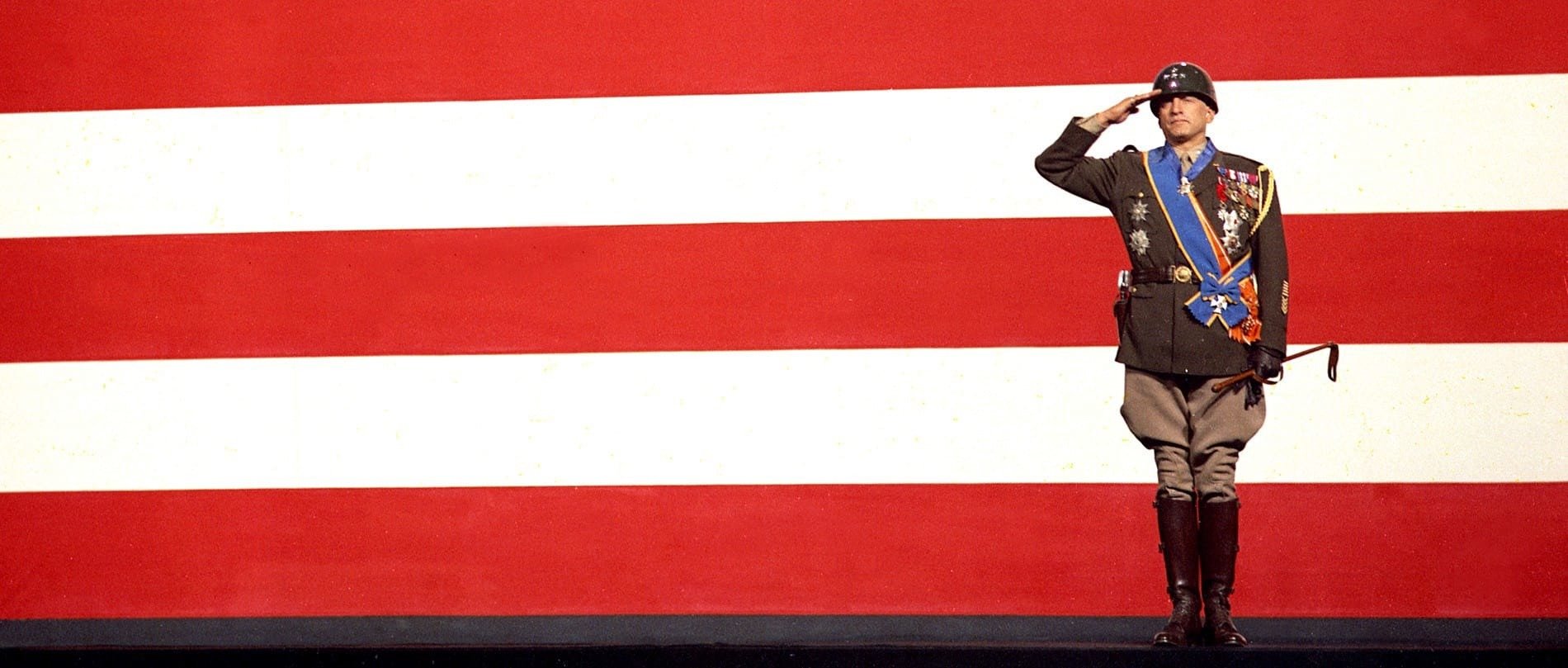

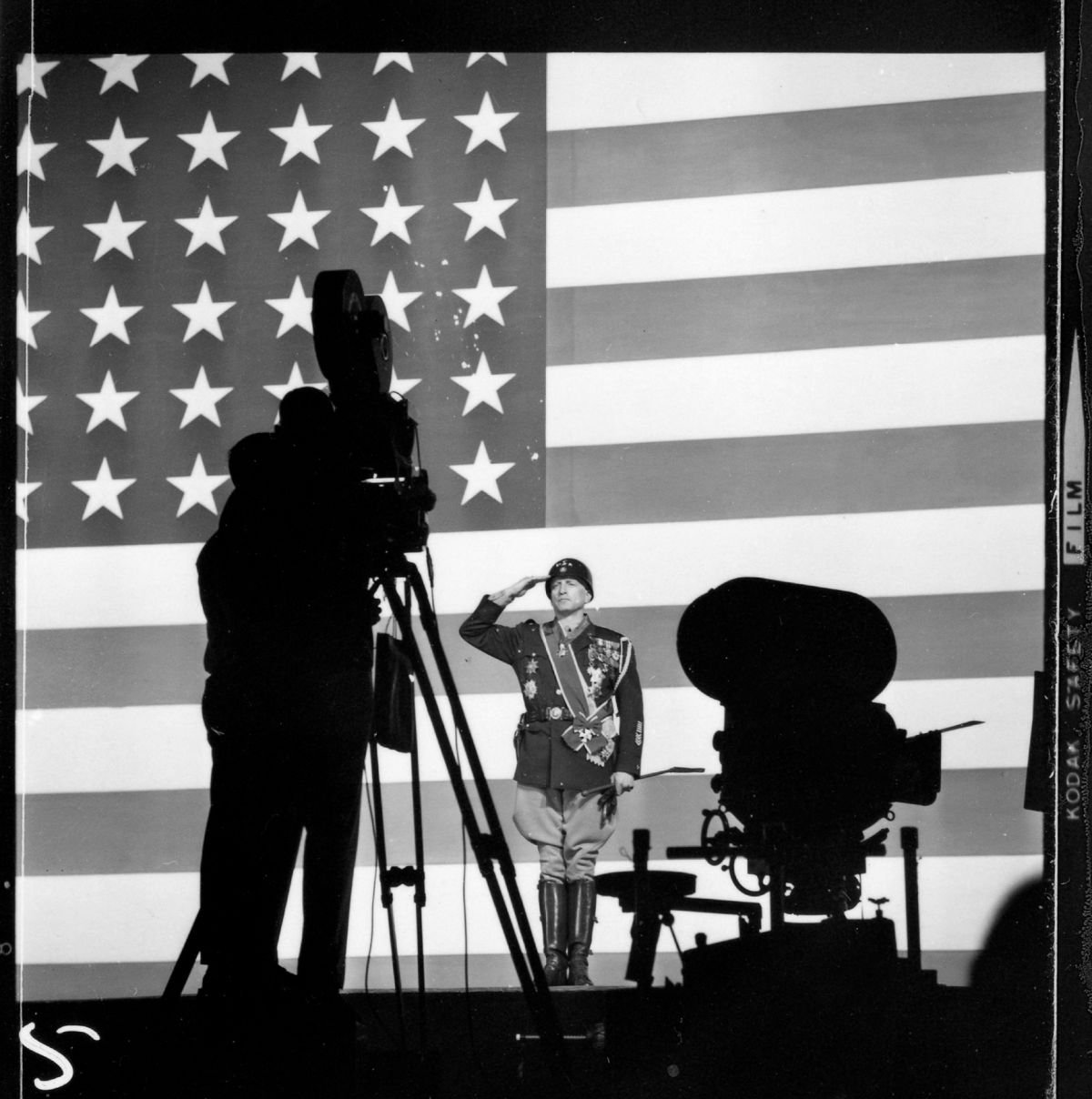

Patton opens with a prologue before the titles appear. The screen is filled with a giant American flag painted on a background. From the bottom of the frame, a tiny figure emerges and strides purposefully forward until we see the full figure of Patton, resplendent in polished helmet liner and an immaculate, bemedaled battle jacket. There is the brace of ivory-handled pistols that was a Patton trademark. And the confident belligerence that Patton projected. Scott's performance in this scene sets the right note for the picture. What follows is an acting tour de force. But one is not conscious that this is just a performance. Instead, one feels that it is real. Scott is Patton. This is acting of the highest order.

Fred Koenekamp is enthusiastic about this powerful opening scene and during a recent interview had this to say to me: "This was an approximately five-minute speech. We shot it in one afternoon in the Sevilla Studios in Madrid. The flag was painted on the back of the stage wall with curtains hung on the sides. It was as big as it looked on the screen — enormous. Scott did this scene perhaps six or eight times for various reasons, either close-ups or something else, and he never flubbed once. Never once! In fact I can't remember him once during the picture flubbing because he didn't remember a line or got confused. He was always right there on the ball just as professional as it was possible to be."

The sharpness and resolution of the D-150 lenses is amply demonstrated in the prologue. There are screen-filling close-ups of Patton's pistols, his decorations, his West Point ring. The clarity of detail, despite the magnification, is amazing. So, too, is the forcefulness of Koenekamp's camera work which seems to emphasize the striking resemblance Scott had to the real-life Patton.

"Actually, without make-up, Scott does not look anything at all like Patton," said Koenekamp. "The makeup people did a remarkable job. Scott's hairline was shaved back, white hair pieces were added and they gave him white eyebrows. His nose was built up, but the most unusual thing was the way his teeth had been changed to look like Patton's. I am told that General Patton's teeth were heavily stained as a result of cigar chewing or something else. Caps were made to cover Scott's teeth giving them this stained appearance. There was a lot of discomfort in all this for Scott, but it is uncanny how much it made him look like Patton."

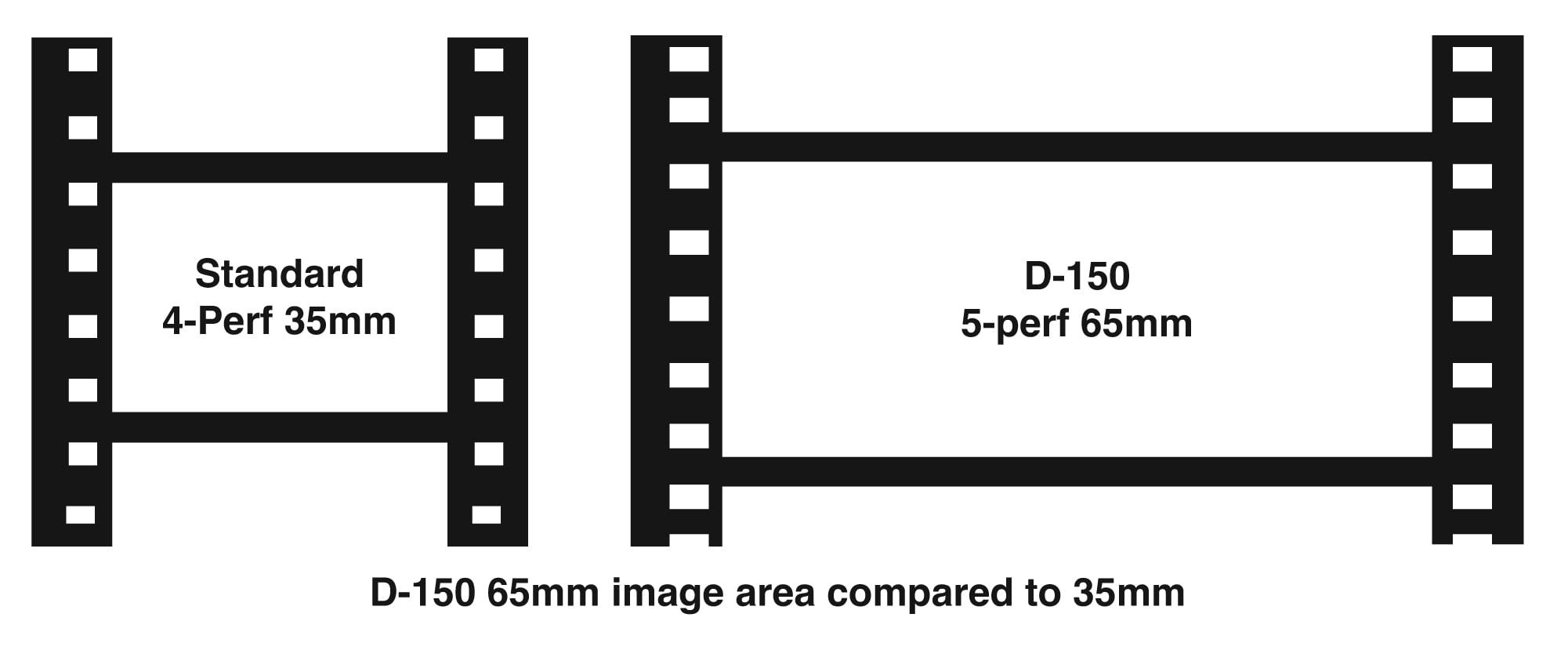

Dimension-150 is a photographic and projection system developed several years ago by two U.C.L.A. staff members, Dr. Richard Vetter and Carl W. Williams. The optical system they designed includes a 150-degree photographic lens (which closely approximates the normal peripheral field of human vision), special projection optics and a patented deeply-curved screen. The combined photographic/projection system provides a virtually distortion free image, and can be adapted to any current theatrical film aspect ratio, including normal 35mm, ’scope and conventional 70mm, as well as Dimension-150. The system offers a complete range of photographic lenses which are adaptable to Todd AO-Mitchell 65mm K cameras.

Patton's highly emotional nature is shown in the infamous incident where he slapped a soldier he suspected of malingering during the Sicilian campaign. It was an episode that almost finished Patton's career. This scene is charged with quiet power and dramatic tension. It is handled with taste and honesty by Scott and Schaffner. And it is one of the relatively few studio-made scenes Koenekamp had to photograph.

In the doghouse because of the slapping incident and awaiting reassignment in England, Patton gets into trouble again albeit innocently. At the dedication of a service club near his headquarters, he ad-libs a little speech on the importance of Anglo-American unity ("...since it is the evident destiny of the British and Americans to rule the world, the better we know each other the better job we will do.") He is accused of slighting the Russians — then our wartime allies — and his enemies howl for his dismissal. But General Eisenhower appreciates Patton’s soldierly qualities and refuses to allow his enemies to claim his scalp.

“This sequence was filmed in the actual place it happened — a red brick building in Knutsford, England, that was Patton's wartime headquarters,” said Koenekamp. “We flew in on a Sunday in beautiful weather. It was overcast the next day when we began shooting. The following day it poured down rain. We finished on Wednesday morning and flew out that afternoon.” Koenekamp brought his crew over from Spain. However, a stand-by British crew was also engaged.

Patton’s incredible advance across France, hard on the heels of the fleeing German Wehrmacht, was filmed in the Pamplona region of Basque Spain. “People have asked me what I did to make the grass look so green," remarks Koenekamp. "The answer is nothing. It looks that way because there is a lot of rainfall in that area. It is near the French border and resembles Normandy and Brittany.”

Actually, Patton was filmed on 71 locations in six countries. The bulk of the photography was done in Spain because only the Spanish Army could provide the necessary World War II equipment (acquired by the Spanish Government under the U.S. Military Assistance Program). Spain also provided a wide variety of landscapes and architecture necessary to simulate the locations of North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France and Germany. Other locations included Morocco where Roman ruins were used and a review of Moroccan troops was filmed; Greece and Sicily where amphibious landing scenes were made. A few scenes, black-and-white newsreel footage, were photographed in Hollywood at the 20th Century-Fox Studio.

Patton is a photographically interesting picture because of the extensive use that was made of natural locations, especially many of the interiors. These scenes have a very realistic quality and a number of the interiors appear to have been filmed solely with existing light. But lights had to be used on all of them.

"I wish you could walk into a location and say, yes, you can shoot it as it is because it is often so beautiful. But you can't do it. To get up to your film speed, you need light.

“Roughly 80 percent of Patton was filmed in natural locations,” said Koenekamp. “We worked in several buildings, such as La Granha and Rio Frio, that are national shrines. We could do nothing that might mar or deface the premises. Consequently we could not use tape, tack lamps to the walls, put up spreaders or do any of the usual things that help in the lighting. Everything had to be from the floor. In this respect, we made extensive use of ‘quartz’ lights, especially the clusters or banks of uni-flood lamps known as FAY globes. We used these lamps in clusters of 6, 9 and 12. Of course, we could always replace the FAY bulbs with regular tungsten globes if necessary.”

All of the lighting units used in Patton were supplied by Mole-Richardson's rental unit in Spain. This included eight 225-amp arcs — the indispensable Brutes. In addition to a regular assortment of conventional studio type lamps — 10Ks, Seniors, Juniors etc — an assortment of "quartz" lights was also available.

Koenekamp was fortunate in being able to bring his long-time gaffer, Gene Stout, to Spain, but the bulk of the electrical crew was Spanish. "The Spanish crew was really quite excellent," says Koenekamp. "They are truly amazing people. If you tell them you want something and it's not immediately available, they will make it even if it means working all night in some foundry or machine shop."

Koenekamp relied on the banks of FAY lights (known as Molefay or MiniBrutes) as daylight fill in some of the more rugged locations where it would have been difficult to haul in the giant Brutes.

for Dimension-150, to be superior equipment

and personally did a great deal of shooting

with it.

"Several years ago when the FAY lights were introduced for the amateur market, I bought a couple from a gaffer at MGM who ran a camera store on the side," says Koenekamp. "I began to use them as a sort of poor-man's booster light. I still have these original lamps and often use them." Like most top professional cinematographers, Koenekamp eschews the use of sun reflectors except to bring out backgrounds and props. He prefers to use either Brutes or the multiple banks of FAY lights because of the greater control and the comfort to the players.

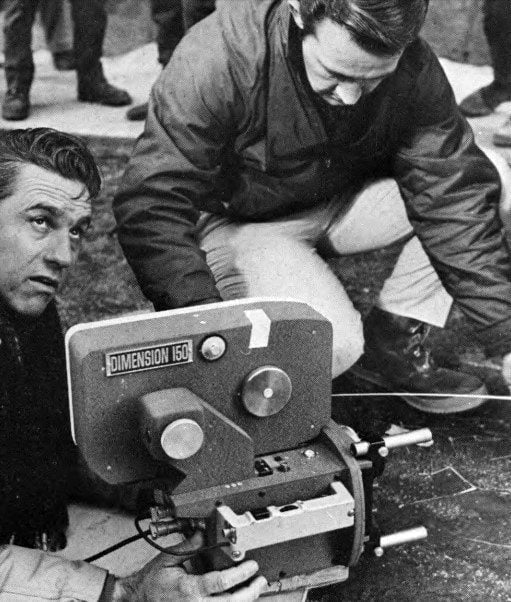

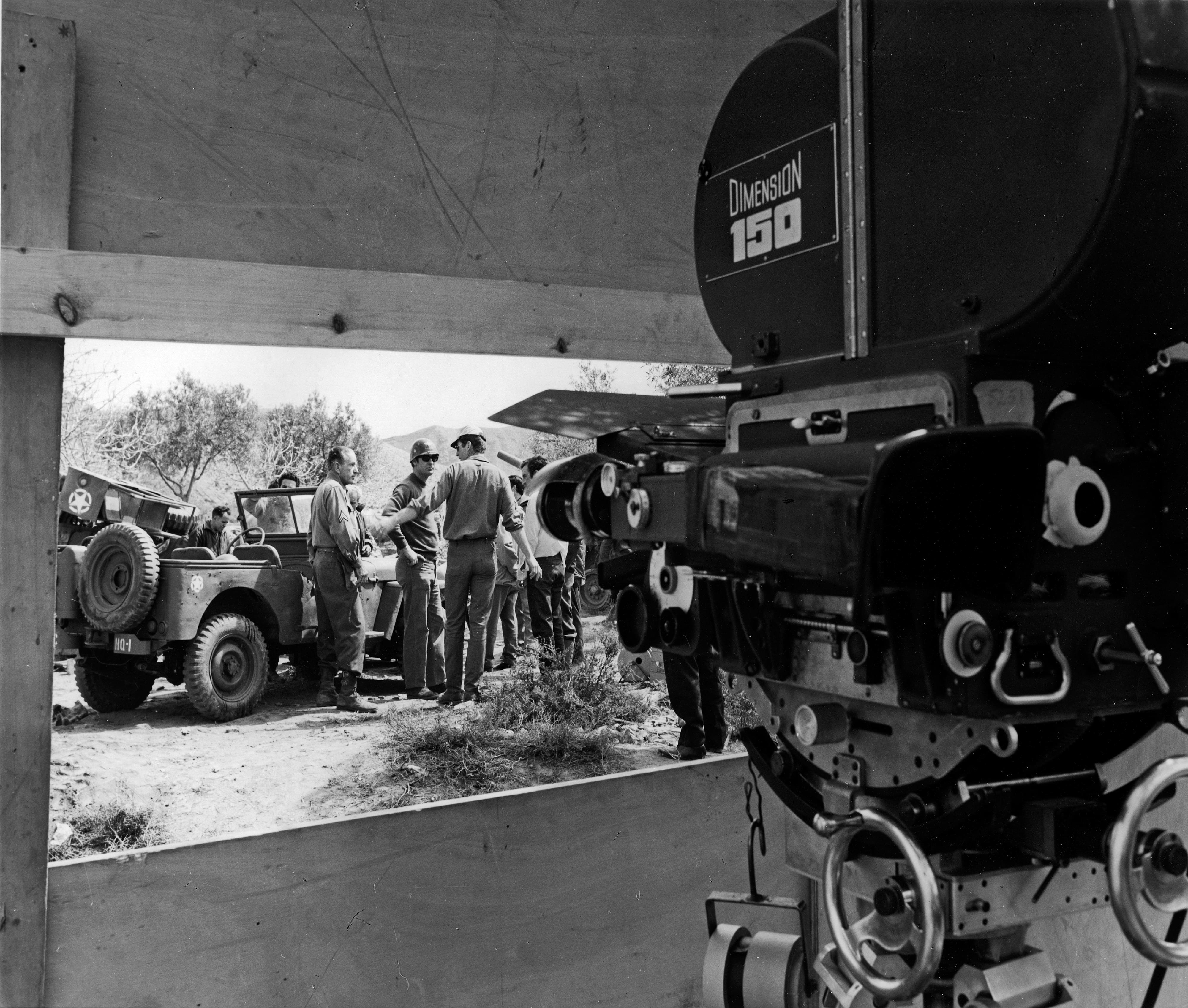

Koenekamp had a full Hollywood camera crew which included Bill Norton, camera operator; and Chuck Arnold, Emilio Calori and Mike Benson, assistant cameramen. These men were backed up by a Spanish crew assigned to man the additional camera equipment. A total of six Todd AO-Mitchell cameras were available: one BFC (the 65mm version of the Mitchell BNC); two FCs (the 65mm counterpart of the Mitchell NC); and three of the small, portable 65mm Todd AO AP (All Purpose) cameras.

"We generally used a total of three cameras on most of the scenes," said Koenekamp. "Bill Norton, an old-timer in the industry, did an exceptionally fine job with the first camera. We had an excellent Spanish camera operator named Ricardo who handled the second camera. He and one of the Spanish assistant cameramen spoke some English which was a big help. As it turned out I ended up operating the small AP hand camera quite a bit of the time."

"I gave the AP one big workout and I'll swear by it. It is a great camera. When it is equipped with a zoom lens, it is an extremely versatile instrument with which you can do quite a bit of work. It weighs in at just under 30 pounds and is easily hand-held; however, I must admit that it does get heavy toward the end of the day. If the zoom lens or any long focus lens is used, it should be mounted on a tripod. With the wide-angle lenses, hand-holding is no problem. I prefer to use this camera without the shoulder brace that comes with it. Generally, I would hand-hold the camera on an approaching tank or vehicle and inch it out of the way of the treads as it passed. When you use the 28mm wide-angle lens you can obtain a very effective shot. For example, I used this technique in the scene at the end of the picture when the farm wagon breaks away and races downhill almost hitting Patton. We made many, many hand-held shots with the AP and I'm surprised at the number that were used in the final picture."

According to Koenekamp, the D-150 lenses are easily adapted to the Todd AO-Mitchell 65mm cameras. The primary lens is an 18mm with a 150-degree angle of view (hence the name "D-150"). Other lenses range from 28mm to a 500mm. There are two zoom lenses: a 60mm-150mm and a 100mm-300mm.

"The D-150 lenses are excellent, especially the 28mm lens," says Koenekamp. "I think that we photographed over half the picture with this particular lens."

Initially, as production got under way, the zoom lenses were not available and were sorely missed. Several were eventually sent over and were put to good use. "We missed the zoom very much, especially when we were doing the Ardennes battles. I personally like the 100mm-300mm zoom best because it has a greater range. Zoom lenses are useful for me because you have so many lens positions at your immediate disposal. It isn't that I like to zoom in and out but that I can rack in on a scene quickly."

The company had a Chapman boom but made very few boom shots. It was extensively used, however, for positioning the camera. The key grip, Glenn Harris, was from Hollywood but bossed a Spanish crew. "Here, once again, I have only the highest praise for the Spanish crew," says Koenekamp. "Once we needed a camera riser for our crab dolly. None was available but this did not stop our Spanish crew. They spent all night making one so it would be available for shooting the next morning."

Patton was a big, complicated picture with many action scenes. Consequently, a second unit headed by Mickey Moore worked very closely under Franklin Schaffner. Clifford Stine, ASC and Cecelio Paniagua, a Spanish cinematographer, worked under Moore's direction handling the second-unit photography. "The second unit worked alongside us all the way," explains Koenekamp. "They filmed the night battle sequence, special stunt work, tanks and vehicles exploding, tanks crashing through walls — things like that. We met in the evening and planned our work together so that we would generally be shooting under the same lighting conditions. I knew Clifford Stine years ago when we both worked at RKO. He actually has retired and now lives in Spain. We were fortunate to have a man like him on the picture."

Weather plays an important part in Patton. "When I first met Franklin Schaffner in his office at 20th Century-Fox studio, I had only very quickly read the script. As we discussed the picture, I happened to mention that in war you can't always wait for the weather. You have to take what comes. Because of this, it was my feeling that we should shoot in any kind of weather. Schaffner told me that I had expressed his thoughts exactly.

"We shot in rain, in snow and slush, and in overcast. There were many times when we had light changes in the middle of a scene when the sun would either come out or go behind a cloud. I let it stay that way without any change in the lens. Of course, I had to keep the actors properly lit and looking their best, but, otherwise, that was it! There was only one time during the picture that we waited for the weather. We had begun filming explosions on a distant hillside when it started to rain. So we waited until the next day when we could finish the scene."

Perhaps the thing that most Patton crew members will remember longest about the location was how cold Spain was that winter.

"Our very first day's shooting was, I believe, February 2, 1969 in Riofrio castle just outside Segovia. We were doing the scene where Patton is having his portrait painted when he receives a telephone call from General Bedell Smith (Edward Binns) telling him he has been relieved of command of Third Army. It was about lunch time and Scott asked for a glass of water. A man brought him one and when he got it the water had frozen! This location was one that had to be lit entirely from the floor with quartz lights. These were placed in every conceivable crevice, doorway, corridor and behind furniture.

"The Battle of the Bulge was filmed a few days after this scene," recalls Koenekamp. "It was staged in the Segovia highlands eighty miles northwest of Madrid on terrain that is quite like the Ardennes. We had to wait several days for the snow but it soon came and with it more cold weather. We had on every piece of clothing we could get on our bodies but by noon we were all shaking with the cold. Franklin Schaffner always had a cigar in his mouth. By afternoon, he was so cold that the cigar was shaking." No fog or effects filters were used on these scenes because it was not necessary. The cameras had all been winterized so they did not mind the cold.

The Battle of El Guettar, a large-scale battle sequence, was filmed in one day in the desert country outside Almeria in Southernmost Spain. Over two thousand members of the Spanish Army were outfitted in German and American uniforms, and an impressive collection of vintage tanks and military equipment was assembled with an eye to as much authenticity as possible. Koenekamp feels that a great deal of credit for the mechanical effects in this sequence should go to special effects chief Alex Weldon. The explosions, shellfire, and small arms action are spectacular. "I saw several tanks on one of the stages at Sevilla Studios," recalls Koenekamp. "They looked like the real thing but as I got up close to them I discovered they had been made of sheet metal and fiber glass by Weldon and his Spanish crew. He had built them from photographs. They were later blown up in the battle scenes."

At this point, it should be noted that the special photographic effects were executed with consummate skill at the 20th Century-Fox California studios by L.B. ("Bill”) Abbott, ASC, and Art Cruikshank, ASC.

"This was the one big battle where the first and second units worked together," said Koenekamp. "I was up on the hill with three cameras shooting down into the valley at the advancing German tanks and infantry. The second unit was concealed in the valley catching close-in action with their three cameras."

In one gripping vignette made from a low angle a German soldier is knocked down by a Mark IV tank and run over. "The second unit was responsible for this shot," says Koenekamp. "Actually, the man fell down accidentally. He was not a stuntman but a Spanish soldier. Apparently, he stopped to cock his rifle and the tank hit him enough to knock him down. The tank kept going but the treads somehow managed to miss the man by inches. He got a torn jacket and was very lucky." This shot was made from a pit and is a good example of the excellent material the second unit contributed to Patton.

Patton contains a number of shots made with long focus lenses showing tanks, vehicles, soldiers on the march. In several instances, Patton is seen marching among them or in his command car. This feeling of compression is effective. "Many times you can get a very nice effect with a long lens by staying back," said Koenekamp. "It pulls things in together—a different effect. It's not something I want to do often but it can be effective if used properly."

In one interesting shot, Patton's command column is seen moving over the crest of a hill, in silhouette, against a sunset. "This shot was made with a 500mm lens. That's why it has a little bit of a fuzzy quality," explains Koenekamp. The field of view of the D-150 prime lens is amply demonstrated in a chapel scene where Patton is seen in prayer just prior to the moment when he apologizes to his troops for the slapping incident. This was done in the medieval chapel at La Granda castle. The ceiling is perhaps sixty-five to seventy feet high and is covered with beautiful religious frescos. The camera points straight up, directly at the ceiling, and very slowly pans over the fresco. "I used the little AP-65 with the 18mm 150-degree lens for this shot," says Koenekamp. "This is the widest lens in the D-150 family so there was a little distortion as we panned, but I think it worked out all right."

Koenekamp, who has worked in virtually all of the wide-screen formats, is an enthusiastic booster of Dimension-150. "It is an excellent wide-screen process and I hope I will have the opportunity of working with it again."

On many of the natural interiors, there was often the vexing and difficult problem of balancing sunlight with artificial light. An example of this occurs in the scene following the battle of El Guettar where Patton meets his new aide-de-camp (Paul Stevens) for the first time. As the scene opens, Patton is standing in a vestibule opening out on a small balcony from which the Mediterranean can be seen. He speaks some dialogue with a player and then moves inside the rather dark, somber Moorish style room, where he meets the aide, speaks some more dialogue, and then walks down a small stairway and into a corridor.

"We did this scene in the Governor's Palace in Almeria," said Koenekamp. "I placed two Brute arc lights in the vestibule to bring Patton into balance with the outside background which was, I think, an f/16 light. This I brought down to f/11 with an 85N3 filter. As the players walk into the room, I covered them with banks of FAY lights. Down the small stairway and along the little corridor, I placed 10K's covered with blue gels. There was a two-stop change coming through the door and into the dark room. I think I went down from F/11 to F/6.3. To be quite honest, this scene turned out to be more than I figured when I looked at the location. I never intended to use the 10Ks and if I'd had more of the FAY lights, I'd have used them instead. As it was I used everything I had. It took the entire camera crew — the operator, the assistant on the focus and myself on the other side of the camera making the lens change. Since we had two dolly moves and the lens change, it was difficult to time out. I think we must have done it around ten times before it worked. I've learned from bitter experience that a lens change has to be absolutely right or it's terrible."

But despite the complexity of this scene, it was done in a morning and by afternoon the company was outside shooting exteriors.

"This picture was not like you'd expect a multi-million-dollar picture to be, where the company sometimes is expected to do only two or three setups a day. We often did as many as 20 to 30 setups. Of course, this did not happen every day, but most of the time we moved right along. The big reason there were no delays was our director, Franklin Schaffner. He was up by five each morning with the day's work carefully outlined on paper. Often he was working with hundreds of extras and many pieces of equipment and he knew every day just where we were and what we were doing. I personally think this was the one man who really made this picture work the way it did.”

There is a truly beautifully lit interior in a long corridor of windows where Patton exits from Eisenhower's office after having been rebuked for the so-called Knutsford incident. His loyal and faithful orderly (James Edwards) patiently waits for him and a very moving and touching scene is played between them. The hallway is long and flanked on one side by many windows. Sunlight streams through them making interesting patterns of light on the polished floor. The walls and ceilings are a soft pastel color and there are beautiful mirrors on one wall.

"This scene was done in the tapestry room at La Granha castle,” comments Koenekamp. "This great hallway is over 100 feet long with a ceiling clearance of 15 feet. We waited until the sun struck the windows at just the right angle throwing patterns of light on the floor. Four Brutes were used. Two were pulled down to full spot and directed at the far wall. The other two were at flood so the foreground was covered. Nets were placed in front of these two arcs since the actors moved close to the camera. The long shot was done with the 28mm lens. For the close-ups, I used FAY lights and a two-inch lens. This scene was shot entirely for daylight balance. No filters were placed over the windows nor did we use i any arcs outside them."

This scene seems to be illuminated solely by the sunlight coming in through the windows — a testament to the skill of the director of photography and his crew. Koenekamp is understandably proud of this scene.

Two other interesting natural interiors were filmed inside an old Spanish fort located in the dead center of Madrid. The buildings had been condemned and were virtually falling apart. This latter point worked to the advantage of the company in one instance by providing a strikingly dramatic set.

While the Battle of the Bulge rages, all of the Allied commanders—including Patton and Bradley — are assembled for a conference in Verdun. This was staged in a barren and bleak room of the old fort. There are white-washed walls. Soft winter light comes through a number of windows that can be observed in the background. Once more Koenekamp used daylight balance. “I used Brutes to match the exterior light coming in through the many windows," explains Koenekamp. "It was an overcast day and after we went to work it started to rain so no correction was needed on the windows. It was supposed to be a cold, somber scene so, again, the weather worked for us."

The riding academy of the old fortress provided the setting for the press conference where Patton made the verbal faux pas that cost him command of the Third Army. A shaft of sunlight streams in through a skylight and strikes Patton, seen riding a beautiful white horse, like a giant spotlight. Around him stand the eager newsmen firing their questions. To capture this episode, Koenekamp once more went the daylight route leaning heavily on Brutes and FAY lights. "We just lucked out when that beam of sunlight came through the window and onto Patton," says Koenekamp. "Once again the weather worked to our advantage."

At the height of the Ardennes counter-offensive, there is a moment in Patton's headquarters when he asks an Army Chaplain to pray for clear weather so Allied planes can attack the Germans. This scene was done in low-key with dramatic shadows playing onto the dark wall of what seemed to be an old wine cellar. "The floor had collapsed in this room and a little gangway had been built over the hole," observes Koenekamp. "You could never build a set to equal this place. That's exactly the way it looked and we left it that way. This scene was done with tungsten balance because I could control the light. The windows were covered. We used our 10Ks and smaller units which made it 100 times easier."

Patton is a film with several hauntingly beautiful moments. My favorite is a somberly photographed scene at a military cemetery in North Africa where Patton and his young aide (Morgan Pauli) speak of the dead soldiers who lie there. "It's lonely out here," Patton remarks. "And cold," replies the younger man, who will soon die in battle. Patton walks to the edge of the desert and stands there thoughtfully looking toward the enemy lines in the half-light of a leaden, foreboding sky. It is a scene played entirely in a long shot and it is poignant and tender. To me, it reveals the compassion and warmth of the director, Franklin Schaffner. I can think of no greater compliment to pay this gifted man than to say that his work in this film is in the finest tradition of the great John Ford.

Koenekamp earned an Academy Award nomination for his expert camerawork in Patton, and later worked again with George C. Scott on the film Islands in the Stream and later photographed Scott’s feature directorial debut, Rage.

The cinematographer was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.