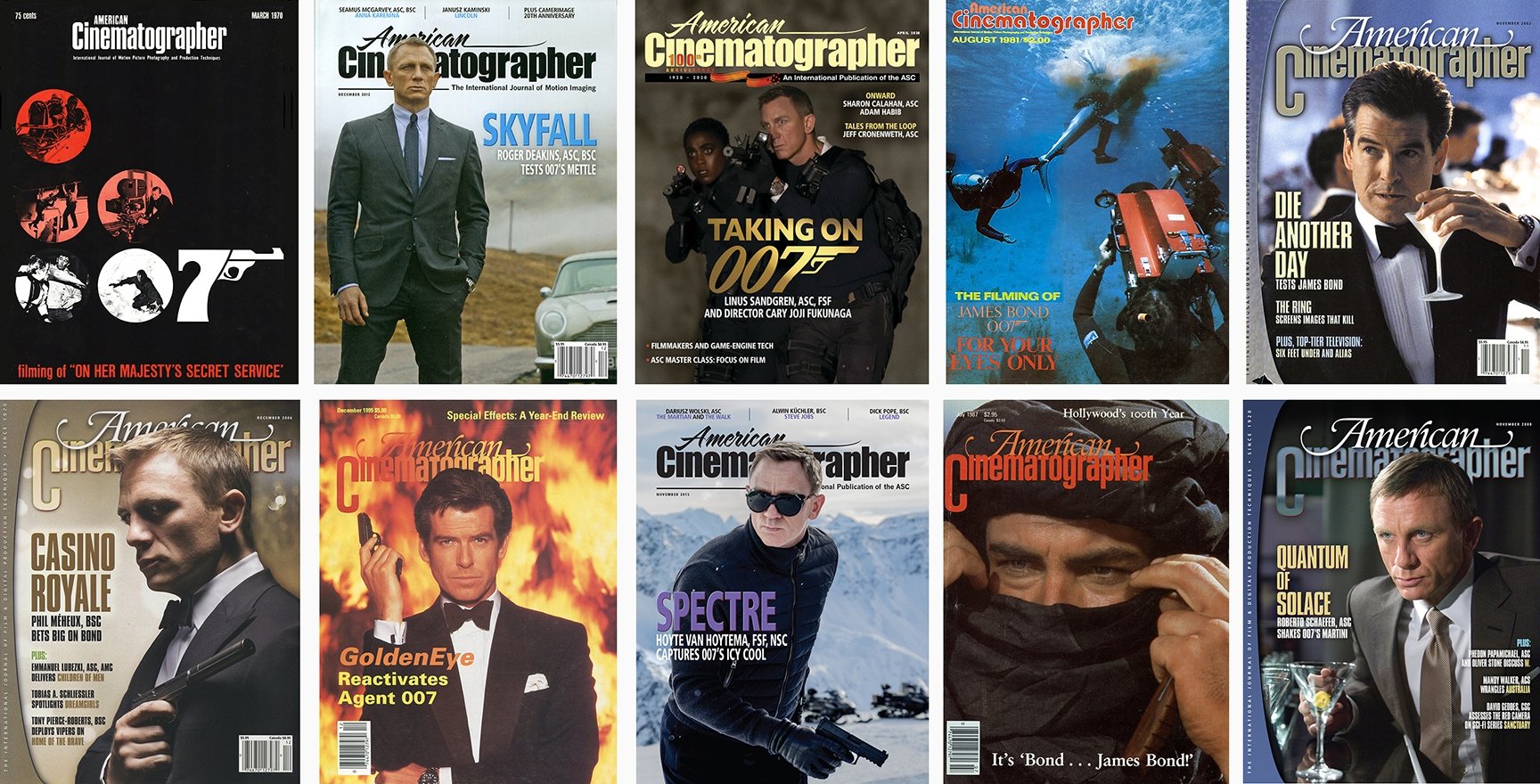

Behind the Scenes of The Spy Who Loved Me — Plus Pinewood’s 007 Stage

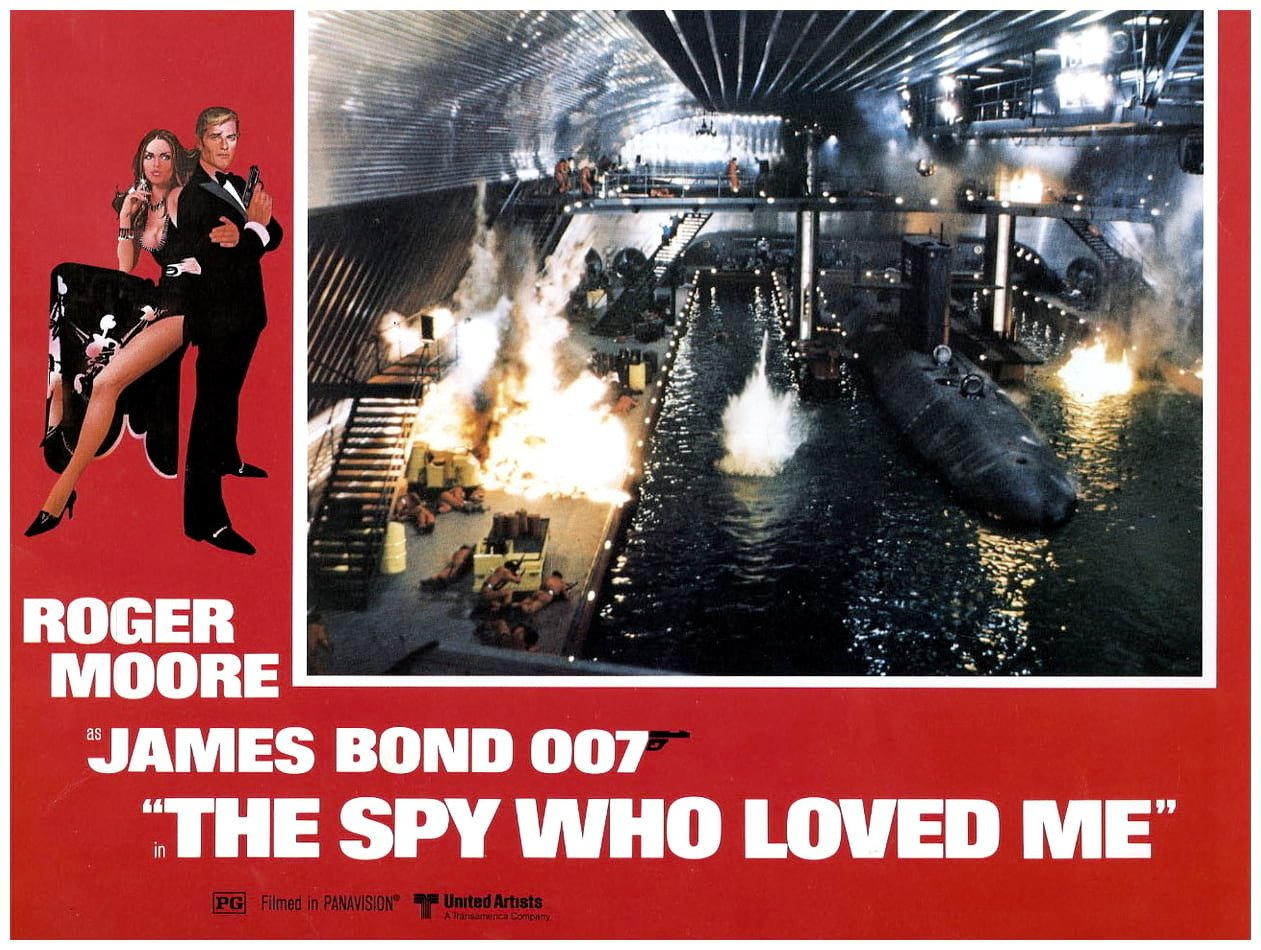

For the latest, splashiest and most expensive James Bond adventure thriller to date, Ian Fleming’s colorful super-spy, the unsinkable “007” hunts kidnapped submarines in the world’s largest sound stage.

Interview by David Samuelson

The enormously successful James Bond films, based on the 007 character created by the late Ian Fleming, are not only great fun to watch, but, from the standpoint of sheer filmmaking, are always technically challenging and innovative.

The latest, and tenth, in the series, Albert R. Broccoli’s production of The Spy Who Loved Me, is the biggest and most expensive James Bond film to date. Bearing out that fact was the construction of the world’s largest sound stage at Pinewood Studios, especially for filming the interiors of a supertanker that “kidnaps” three nuclear submarines.

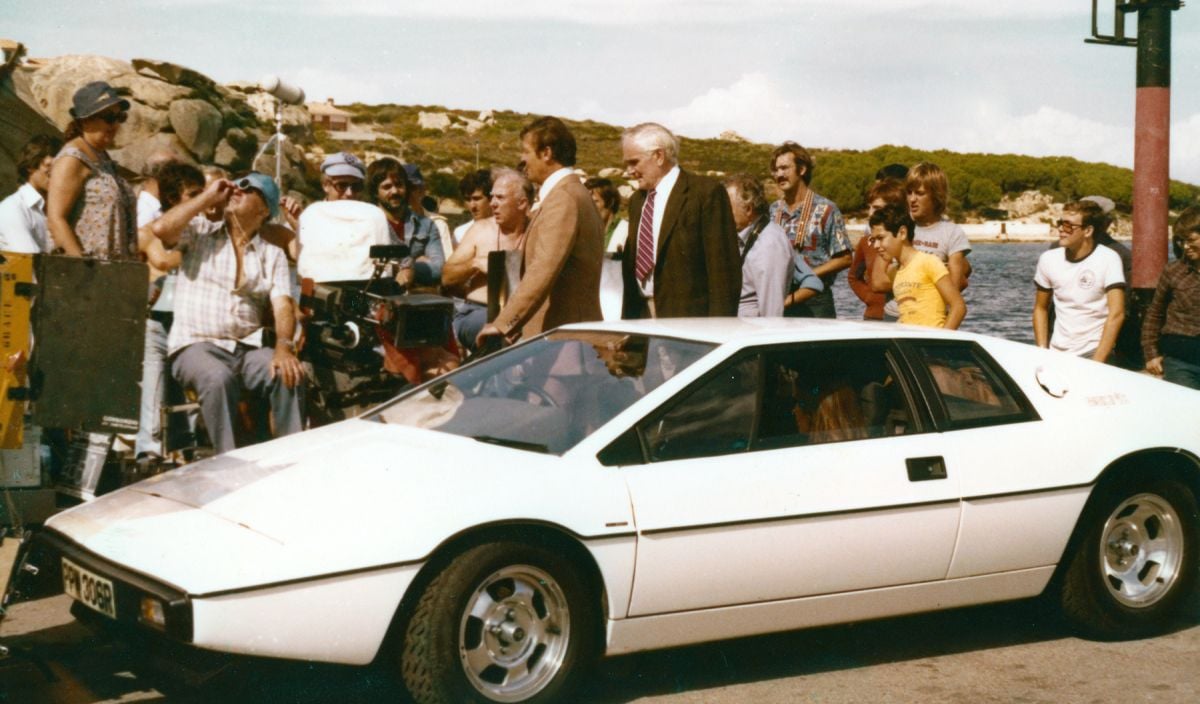

The principal locations for The Spy Who Loved Me were Egypt and Sardinia, where major first-unit shooting took place over a five-week period.

The studio and set-construction was once again done at Pinewood Studios (more on that below) in the Buckinghamshire countryside outside of London. Pinewood has been an essential ingredient in the James Bond chemistry from the very beginning of the film series, as it was here that the fantastic sets and brilliant special effects were created for the previous successes.

Other locations for the film included Faslane Submarine Base on the Clyde River on the southwest coast of Scotland in the vicinity of Glasgow, where the Royal Navy super-secret base for Polaris nuclear submarines is located. It is a small miracle that permission was granted for shooting certain scenes which would have cost millions of dollars to reproduce elsewhere. Exteriors of a 600,000 ton supertanker were shot at sea in the Bay of Biscay off the coast of France, Spain and Portugal.

One of the most unusual locations was 20 miles north of the Arctic Circle — Baffin Island, a sparsely populated province of Canada. Here, in a national reserve of extraordinary mountain peaks, a film unit was based in the town of Pangnirtung, with the services of two helicopters and ski-jump expert, Rick Sylvester, at its disposal for the shooting of an opening sequence for the film.

The Egyptian locations included the streets of Cairo, the Great Pyramids of Gizah, the temple of Ramses II in Luxor and the ruins of Karnak, as well as a cruise down the Nile River aboard a “felucca.”

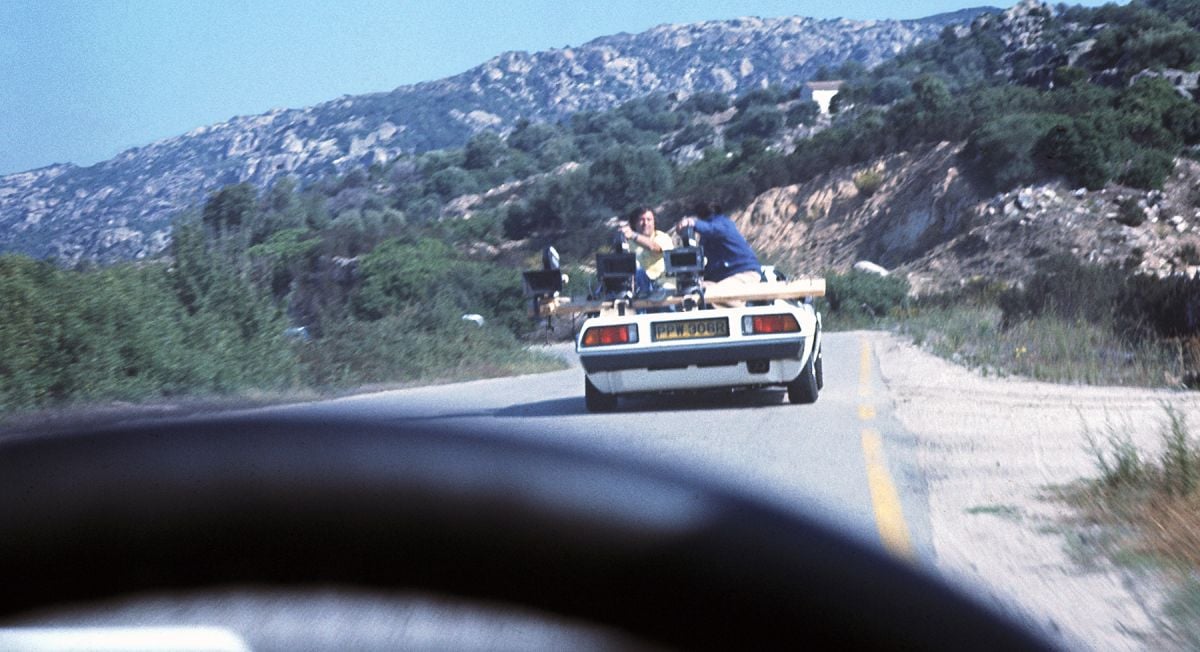

The Italian island of Sardinia in the Tyrennean Sea was featured as the location of the film’s most spectacular chase sequence, taking place on hair-raising cliffside roads along the seacoast.

Commander James Bond drives a new model Lotus Esprit, capable of tricks unknown to his previously renowned Aston Martin, and is pursued by a Kawasaki 900 equipped with special sidecar. Just off-shore is “Atlantis,” a spider-shaped marine biology laboratory, the headquarters of a mysterious Nordic shipping magnate.

Two additional film units were at work simultaneously for two-month periods. One shot in Plymouth harbor, and then tracked the first unit to Sardinia and Egypt, specializing in action scenes. Another crew, based out of Nassau in the Bahamas, was under the supervision of Michael Wilson, special assistant to the producer. Another Bond regular, Lamar Boren, who worked on underwater sequences of Thunderball and You Only Live Twice, was once again behind the cameras during a 16-week shooting schedule.

On the back-lot at Pinewood, there is a wooden hut with peeling paint dating from the Second World War, which bears the discreet designation: SPECIAL EFFECTS. It is here that the mad ideas of the scriptwriter, director and production designer are transformed into reality by Derek Meddings and his boys. [You'll find our complete story on this work, written by Meddings, here.]

The armourer, Q, when time comes to equip James Bond for his latest mission, would be lost without Derek. A whole series of weapons and gimmicks were in the course of preparation for months, awaiting their unveiling at the release of the film.

The Wetbike is being introduced by James Bond in The Spy Who Loved Me. This is Nelson Tyler’s latest invention, straight off the beaches of Southern California — a motorcycle on waterskis.

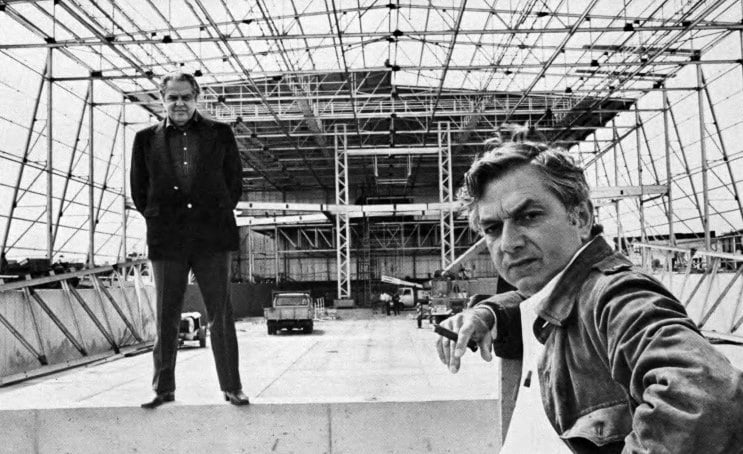

During the phase of filming that took place at Pinewood Studios, American Cinematographer contributing editor David Samuelson conducted the following joint interview with production designer Ken Adam and director of photography Claude Renoir:

American Cinematographer: A sound stage nearly six cricket pitches long and two-and-a-half cricket pitches wide is unique to the industry — to say the least — and a facility the size of the new 007 Stage at Pinewood is obviously a major investment in the future of film-making in the grand manner. I can understand why it was necessary for the current Bond picture, but do you anticipate other such large-scale productions developing in the future?

KEN ADAM: Yes. I can’t specifically name them at the moment, but obviously, certain other producers would like to use the stage. I feel that there is a tendency for certain creative directors to go back to the studio type of picture because, with television and new camera lenses and commercials, real life has been so much exploited. You see seascapes, landscapes, mountainscapes — all beautifully portrayed on television and in documentary films — whereas, a studio can provide a form of magic, of artificiality. You have only to look at the Bugsy Malone musical, which re-created the 1930s, or a Fritz Lang picture of the ’20s to realize that the studio-made film provides a special kind of entertainment — a form of escapism, I think. A lot of directors feel the time has come to go back to the studio-type of picture. Fellini never shoots anywhere else now but in the studio, and even Kubrick is getting to think that way.

CLAUDE RENOIR: You know, I have done pictures in France with directors who, up to now, have never made a picture in a studio. One of them told me: “I’m not sure I can shoot in a studio. I have never done so and I don’t know what to do with a set.” They are very young people, all of them, and they are doing well, but they do not want to go into a studio. Of course, in France we have no more studios. We shoot in houses or flats or anyplace — but we manage quite well.

In the same way that a director may have certain qualms when he considers going into a studio, do you feel, when you look at something the size of the 007 Stage, “How on earth am I going to light it?"

RENOIR: That set is completely closed on top and we show the ceiling in most of the shots, so the problem is the same as it is in some real-life locations — no place to put lights, without showing them in the picture. There is no room for big lamps, so I am using a lot of very small lamps and the practicals in the scene. For example, we are using between 9,000 and 10,000 amps of light, and for a long shot we are surrounded with lights, but I don’t use more than 12 to 15 10Ks. The rest are only 2Ks or 1,000-watt Redhead quartz lights or nine-lights.

Not a single Brute?

RENOIR: No.

ADAM: The more natural a set can look, the better it is. The theory that you have to see every angle of the set is old-fashioned. To create an atmosphere and to have it look as natural as possible, it is necessary to have natural lighting. Unnatural lighting makes the result look unnatural. I felt that, on this set, I should give Claude as much practical lighting as possible because, otherwise, it wouldn’t look effective. I also gave him a lot of reflective surfaces. I started him off with other sets which had reflective surfaces so that he could play about and experiment, because I think it’s exciting to see flares and reflections.

RENOIR: Where you cannot put light, it is much better not to put light than to put too much.

ADAM: On this big set we have a major light change. When the submarine enters the set it is in relative darkness, and then the lights go on and expose the whole set. To my way of thinking, when Claude kept the set dark it looked more dramatic than when all the lights went on. In my earlier days as a designer, I tried to make it possible to see every detail of the set, and the first person who really said I was wrong was Stanley Kubrick. He knows a lot about photography and I had to agree with him and ever since then I haven’t cared about beautiful, long shots. I am much more interested in the composition of the shot. Hopefully, I give cameramen the elements to compose on and to create dramatic lighting. I think that’s much more important than seeing every little detail.

More economical, too!

ADAM: Well, I don’t know about that — because you still have to have all the elements there.

But isn’t it part of the production designers art to consider “value-for-money” on the screen?

ADAM: It depends on the sort of picture you’re making. If you are going to do a Bond film nowadays, you’ve got to go in for big spectacle and big sets, but you’ve got to think a bit and find out which is the best way of achieving this, as you can easily go overboard. On pictures like this you do gain a certain amount of experience, and you try to ensure that if you make the production spend a lot of money, all that money will end up on the screen. Nothing is more disastrous than spending a lot of money and then finding that the production value is not on the screen. Nothing is worse than spending money in the wrong direction.

Is it up to you as to whether a picture is shot principally on location or in the studio?

ADAM: Well, that’s one of the mysteries of filming. My theory is that very often it is more economical to build a set and shoot in the studio than to use a location where a lot of additional charges are involved. I don’t think one can generalize, but my feeling is that, in the case of a picture like Barry Lyndon, we probably could have filmed that one more economically by using a series of great locations and some fabulous interiors of stately homes, but done the rest in the studio. To my mind, it would have been more economical than doing the whole picture on location, as we did, and I think that Stanley Kubrick now feels the same way. People are coming back to the studio to get escapism, but I think it is for economic reasons, as well. When I did The Owl And The Pussycat in New York, it was affirmed that the picture should be done basically on location, but the interiors were built in a New York studio. Now, that picture was, hopefully, a successful combination of studio and location. There are no hard and fast rules, but I think that if you want to create escapism, then very often you can achieve that better in a studio.

Claude, how do you feel about shooting on location as compared to shooting in the studio?

RENOIR: Well, for a lighting cameraman, it is much more wonderful to work on a studio stage, because you can do with the lights exactly what you want. It’s sometimes nice to work on location, especially in a beautiful country, but you have to accept the weather as it is. You cannot always control it, so what ends up on the film is not absolutely under your control. Really, I much prefer to work indoors, in the studio, because you can work precisely as you want to.

Can you describe, in general, the style of photography you are using on The Spy Who Loved Me?

RENOIR: It is very difficult to answer that kind of question, because I use a different style on every picture I do. But I never think about it before starting the picture. It comes by itself, according to how well I understand the script — and how much I like or dislike the director. In this case the director is Lewis Gilbert, with whom I have done many pictures. I know him very well and I know what he wants. That’s a big help for a cameraman. As for style — when starting a picture I always think that I will not do anything very different, but it always comes out different. It’s not a matter of lighting; it’s a matter of understanding the story. On this one I’m not doing especially tricky things. I’m just trying to understand what’s needed and doing my best. That’s all.

Have you been influenced at all by the previous Bond films that have been made?

RENOIR: No. I like very much what I have seen in some of the Bond films, but I prefer not to think about them, and do it my way. Even if they are very good, you must never try to do the same. It is better to do it your own way. Sometimes it may be worse — but at least it’s different.

Do you find it very different to work here in England, as compared to working in France?

RENOIR: I worked here quite a long time ago on Cleopatra [AC, July '63] and I have no problem at all here. In fact, for me it is even a little bit easier. In France, for example, when I need something I have to think about it for a week in advance so that it will be ready. Here, you just ask and you’ve got it. But as for working in different countries — I’ve worked in Spain; I’ve worked in California, and in Miami once. For the cameraman, it is all the same. Film is an international dialect.

Search for an enclosure spacious enough to contain the latest shenanigans of James Bond scored zero — so the world’s largest sound stage was built.

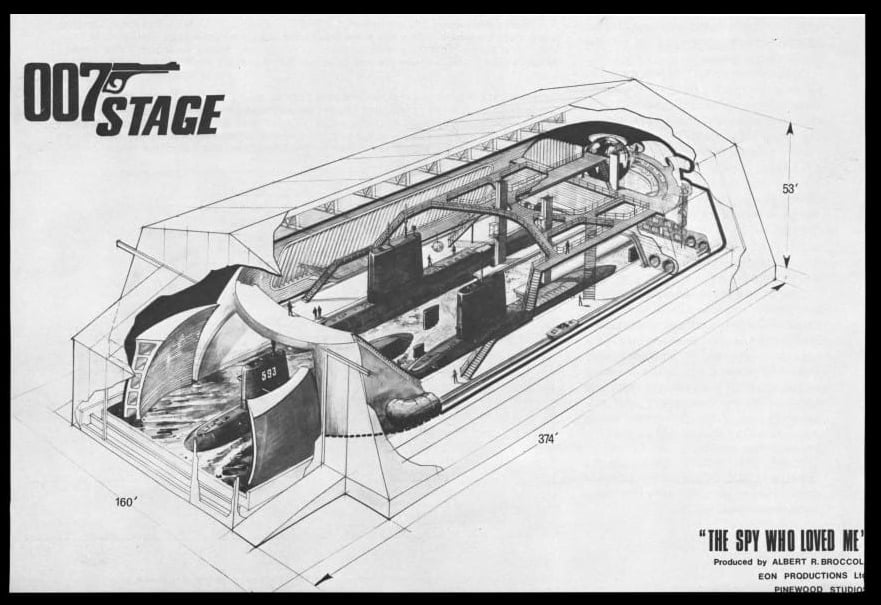

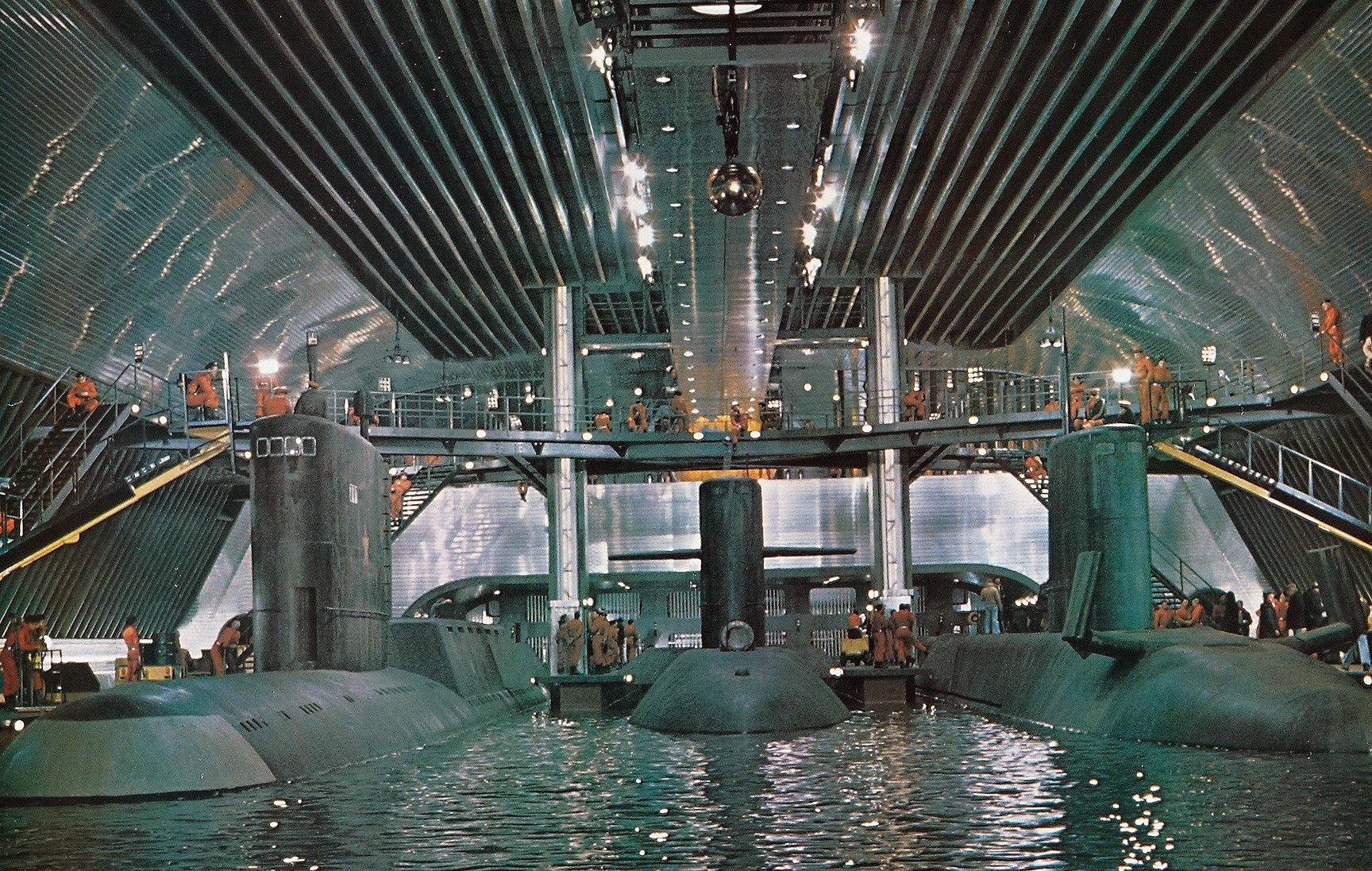

Like a submarine breaking surface alongside a lot of other big ships, the silver-sided 007 Stage heaved into sight on the Pinewood Studio lot in Buckinghamshire, England. It’s the world’s biggest film stage, built to house the expansive thinking of producer Albert R. Broccoli, his production designer, Ken Adam, and their gargantuan piece of design and engineering for The Spy Who Loved Me. It’s the first film stage to be built in the western world for eight years. It had to be if Cubby Broccoli’s ideas for his tenth and current Bond film were to become reality. There was no other film stage which could take in the set design, which includes 1,200,000 gallons of water, a massive area of a full-scale 600,000-ton oil tanker, one United States nuclear submarine, one British nuclear submarine and one Soviet nuclear submarine, and hundreds of people - ships’ crews and film crews.

Because there were no film stages big enough, Cubby and Ken Adam circumnavigated whole areas of Britain and some continental countries for a structure to house their towering designs, but as Cubby Broccoli says: “We saw a lot of people and places. They couldn’t promise anything. We told them we had to dig a big tank to take in the water and we’d have to have a guaranteed period. It became absolute farce. So it appeared to me it was more sane, after talking to the United Artists people, to explore the possibility of putting up a new stage. At that time we were hoping that the Rank Organisation would come in with us. They decided we could built the stage on the studio lot and we would control it; we — Eon Productions and United Artists — would be able to rent it out, so we went for it.”

A young architect, Michael Brown, who had designed some of the world’s most sophisticated film and television stages, was called in to work with Ken Adam, whose studio art department was taking on the shape of a shipyard design centre.

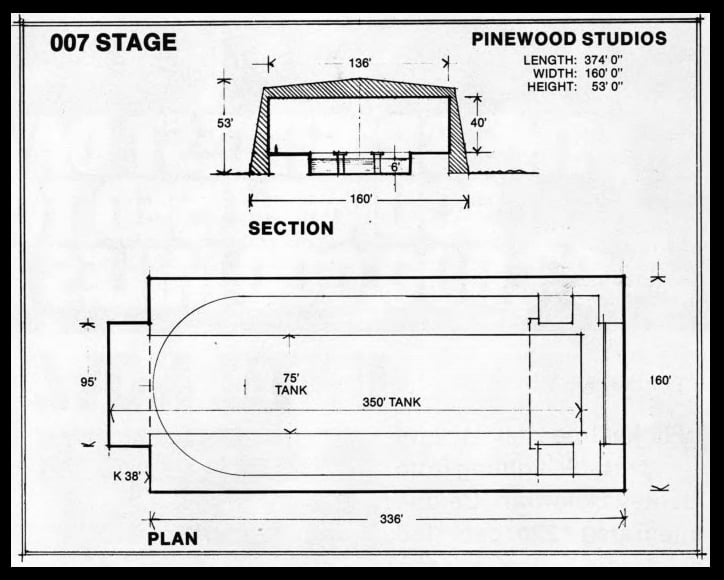

Appropriately enough, the new stage was baptised Number 007. It is 336 ft long, plus an exterior tank of 38 ft., making an overall length of 374 ft., with a width of 160 ft. and a height of 53 ft.

As a basis of comparison, the largest stage hitherto in England is at Shepperton Studios (used for Space Odyssey and Oliver) — the “H” stage, with dimensions of 250x119x45 ft. At Cinecitta in Rome (where Cleopatra and Ben-Hur were shot), the Number 5 stage is 261x118x45 ft. The largest in Hollywood is MGM Stage 15, which is 311x136x40 ft.

Before the construction decision was taken, various industrial sites were considered, including an old RAF facility where World War II dirigibles are still being stored.

Government authorities had to scrutinize the stage plans before permission could be given for the go ahead; this was given, and, to Cubby’s knowledge, this means that United Artists, along with Cubby’s Eon Productions, now own their only film production property — the 007 Stage.

Says Broccoli, “We didn’t just go into it as a matter of investment; we did it because of the specific needs of this picture — and hopefully we will ultimately recoup what we have invested in it. We will keep the stage as long as possible over the years. United Artists and Eon will rent the 007 Stage through the guidance of Rank. The purpose is to keep it up and make a profit out of it, because I think a stage of this size is important in a studio that is alive like Pinewood.”

When the glistening steel work for the new stage was being bolted during the parched summer in Britain, and not a cloud was forecast for months, the Government decreed an emergency situation with the nation’s taps and rationed the fast-disappearing water.

Meanwhile, the water tank under the 007 Stage was being bored out to take more than a million gallons of water — itself a reservoir many towns in Britain would have prayed for. Urgent question, as weather forecasters gloomily shook heads to hopeful enquirers for rain: “Where are the 1,200,000 gallons of water coming from for this oceanic Bond scene?” The answer, in two senses, was subterranean. Very few people knew that right underneath the stage there are millions of gallons of well water, and the studio has a license to draw it at the rate of 30,000,000 gallons a year for studio purposes, and when it has been drawn it is banked for repeated use.

Constructed by Specialist Builders of Uxbridge, and requiring seven months to completion, the new structure cost $1,650,000, including a setting of the interior of a super-tanker which has kidnapped three nuclear submarines. This is the largest interior set ever built for a film.

The problems, one after the other, were overcome for The Spy Who Loved Me. Cubby said, “We are happy the stage is up. We think that it’s not only a boon to our picture, but a boon to the industry as a whole that there exists such a fine piece of equipment to work in. Pinewood is excited by the idea that it is there, because it enhances the studio facilities. It also provides the opportunity to bring people into the studio where they can work in the winter and create all kinds of things hitherto imposssible. Pinewood is the epitome of production, and if we who work here and those who own interests in Rank don’t help the industry to survive, then, hell, all’s lost. I’m delighted to see that Rank is turning down offers for the sale of the studios.”

Cubby Broccoli, who is quite a few avuncular strides ahead of most broad canvas producers, was very proud of his massive volcano set which changed the skyline of Pinewood for You Only Live Twice. But he says that it is a greater stroke of design and engineering to build both the 007 stage and the set. “The interior is a terrific piece of work,” he says with pride. The whole screen time for the set will be about 20 minutes out of two hours, 10 minutes.

Ken Adam’s design depicts a huge section of a 600,000-ton oil tanker, the Liparus, belonging to a perfidious multi-millionaire who has a frenetic belief in one-downmanship. His grand design is that the world’s population — or a lot of it — should live beneath the oceans. The far-ranging Liparus doesn’t take on oil. Instead, like a big fish swallowing little fish, it has a bow which opens to swallow submarines and store them in its cavernous inside...the British nuclear submarine HMS Ranger, the American nuclear submarine USS Wayne, and the Soviet nuclear submarine Potempkin. And from the script of Richard Maibaum and Christopher Wood comes this scene, and set, built on the massive 007 Stage at Pinewood:

The vast dim interior of the Liparus is suddenly brilliantly illuminated as giant floodlights are switched on. Almost the entire width of the vessel and a considerable proportion of its length is one huge sea-filled dock. The middle portion of the dock is now occupied by the Wayne. On either side of her are berthed the British submarine Ranger and the USSR submarine Potempkin. Along the length of the dock on both sides are gangways with steel stairways and elevators running up to catwalks extending the length of the vessel, connected at intervals by cross walks. Between the dockside gangways and the hull runs a hovercar track, enclosed in a tube running the full length of the vessel on both sides of the dock. There are gaps in the tube at certain points to allow access to the hover cars.

The British and American submarines have been constructed at Pinewood under the supervision of naval experts, and, as Cubby says, “within the scope of state secrets we are operating under their guidance,” But so far as the awesome interior of the tanker is concerned, Cubby agrees it’s a figment of their imagination “to help us in our film.” In fact he thinks the whole thing is “quite extraordinary”.

Inauguration of the world’s largest film stage took place at Pinewood Studios with former British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, James Bond star Roger Moore and Producer Albert R. Broccoli in attendance.

Participating in the launching was Mrs. Albert R. Broccoli, who broke the champagne bottle on the conning tower of the American “hunter-killer” submarine and leading actors from the film, including Roger Moore’s co-stars, Barbara Bach, Curt Jurgens and Caroline Munro.

Many British actors who made their reputations at Pinewood were present, including Jessie Matthews, John Mills, Kenneth More, Hayley Mills, Donald Sinden, Ann Todd and Richard Todd. Also in attendance were several dignitaries from the British Royal Navy, as well as a contingent of 24 marching men from the Band of H.M. Royal Marines Commander in Chief Fleet, led by Captain Christopher J. Taylor, Director of Music, and W/02 Bandmaster Anthony Ivor Kendrick.