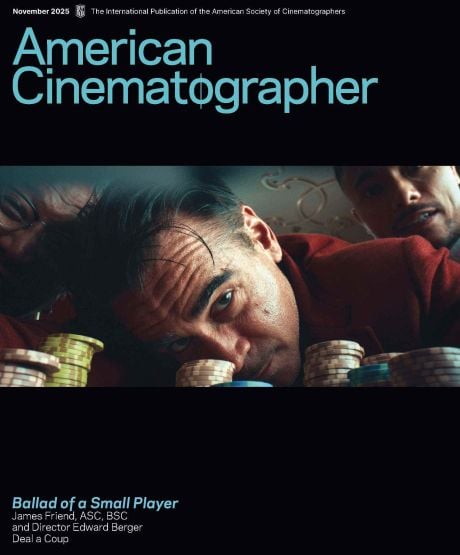

The Taste of Things: A Feast for the Eyes

With lighting as a key ingredient, Jonathan Ricquebourg, AFC and writer-director Trần Anh Hùng deliver a delectable romance.

All images courtesy of IFC Films. Unit stills by Carole Bethuel and Stephanie Branchu.

Jonathan Ricquebourg, AFC never doubted that The Taste of Things would be an impassioned ode to gastronomy. But he also understood that his cinematography could not surrender the picture to food alone. The movie’s “philosophical spirit,” he says, was described for him plainly by director Trần Anh Hùng: “One of the first things he said to me was, ‘Everything is important. Everything matters.’ We talked about how every element of the image needed to be emphasized: the heat of the kitchen, the coldness of water, the textures of flowers or stones — and, of course, the characters in the frame. For Hùng, movies are a very physical experience. He wanted to create the feeling of being inside this movie, existing as part of its world.”

The world of The Taste of Things is indeed one in which cooking, and eating, constitute a way of life. Couched in the quiet countryside of late-19th-century France, the film brings viewers intimately into the kitchen of renowned gourmet Dodin Bouffant (Benoît Magimel) and his longtime chef, Eugénie (Juliette Binoche) — where each feat of culinary expression sows another seed of their long-budding romance that, for 20 years, has not yet blossomed into marriage. Beyond that kitchen’s four walls, however, are sites of equal importance, from the dining room where the pair’s epicurean friends assemble for meals, to the verdant forests that encircle their estate. In all of these spaces, Ricquebourg says, “light and color had to be part of every emotion. And Hùng told me, ‘I want beauty, but the rest is up to you. The light belongs to you — you own it.’ That was very trusting of him, because we had never worked together before. And it was amazing for me, because it meant that the light and its poetry could become a subject on its own.”

A Set for the Sun

With prep underway, Ricquebourg found himself chiefly concerned with how best to accentuate the presence of the sun as the narrative unfolds. “This is a day-to-day story about everyday life — about a couple who work together and love one another,” the cinematographer says. “So, we needed to capture the mood of the sun as it moves throughout the day.”

A prime example of this is the film’s grand introduction of brilliant sunlight, as Eugénie, Dodin and their assistants — Violette (Galatéa Bellugi) and Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire) — settle into the radiant kitchen, where the sun’s beams increasingly brighten and spill over tables, counters and stovetops as they prepare for the laborious day ahead.

“All the meals seen in the movie are real, and we only had a few minutes to shoot before each meal would expire. After that, the magic disappears.”

— Jonathan Ricquebourg, AFC

The production’s main set — the historic Château de Raguin, located in the department of Maine-et-Loire in western France — had been chosen by the time Ricquebourg joined the crew, but he notes that the springtime shoot and the kitchen’s eastern exposure offered some early assurances of how he could use and supplement the natural light for these mood-setting shots: “The main set gave us two small eastern-exposed windows on either side of the front door — so, I decided that in most of our daytime kitchen scenes, the door had to be open all the time." Opening the entryway helped not only to fill such interiors with warm illumination, but to enhance the film’s period details, as well. “People of that era generally left their doors open and walked freely in and out of them,” Ricquebourg explains. “Of course, if they didn’t, they’d have much more need for candlelight, and they usually didn’t want to burn candles all day long. And in our castle location, where daytime can easily become full of darkness, we didn’t want candles burning all day, either. We wanted sunlight to go through the whole set.

“One of the things that was most important for Hùng is that when there is sun, we need to feel the sun,” Ricquebourg continues. With this principle in mind, he and gaffer Georges Harnack used four 16K Dino lights, four 9K Maxi Brutes and multiple Arri SkyPanel S360s, which were primarily rigged on cherry pickers outside the windows and door of the kitchen set. Harnack notes that on the lifts, these fixtures “could go up to 26 meters [85 feet], but we often used them low and horizontally, just above the windows, which were on the ground floor. And we also had Dinos on Long John [rolling crank stands].” Ricquebourg would have fixtures turned off and on, as appropriate, depending on the time of day. Whenever possible, the filmmakers used natural sunlight, “which is irreplaceable,” the cinematographer says.

A Moveable Feast

Ricquebourg’s sunlight-centric strategy carries over to the film’s first cooking sequence — an immersive walk through the making of an exquisite four-course meal and its subsequent tasting. Spanning roughly 25 minutes of runtime, the scene showcases Eugénie’s artful orchestration of order in the kitchen, as she prepares and plates each dish in concert with Pauline, Violette and Dodin, who lend their helping hands. (The scene’s only cutaways from this action are to the upstairs dining room, where Dodin soon heads to host the group of friends who will partake in the feast.) The filmmakers structured most of this savory set piece around the actors’ choreographed movement through the kitchen, and Ricquebourg says that his ambient approach to lighting aided in this effort: “We thought of the choreography as a way to show the relationship between these characters, so we wanted to see all of the steps they take to make the meal. And I wanted the actors to be free to perform all of those steps without any stands on the set.

“To guarantee a homogenous exposure throughout the room, the Dinos had to penetrate from as far and as low as possible,” Ricquebourg continues, “and we added four shallow light boxes on the ceiling.” Harnack notes that these light boxes “consisted of [Rosco] DMG Lumiere Mixes with unbleached muslin, which served as ambient fill far away from the windows. For ambient fill close to the windows, we had 9K HMIs bouncing on Ultrabounce solids, rigged just above the windows.” The crew also concealed Astera Titan Tubes behind furniture — a technique that Harnack says helped “reproduce the bouncing of sunlight.”

Ricquebourg also decided to capture the majority of the sequence on Steadicam, which meant that freedom of movement would be as important to the crew as it was to the actors. Steadicam operator Florian Berthellot was tasked with weaving in and out of the kitchen’s hotspots of activity — panning over crayfish as they’re dropped into a pot to become consommé; pushing in on the straining of butter and the flaming of wine; and tracking a loin of veal as it’s periodically pushed in and pulled out of the oven until roasted to perfection.

“When you use one lens most of the time, the editing is so smooth, gentle and delicate. So, it’s really something I push the director to do.”

Ricquebourg notes that he and Hùng settled on this shooting scheme after spending two weeks of prep time at the Hôtel Balzac’s restaurant, run by famed French chef Pierre Gagnaire — who served as the production’s “gastronomic manager” and makes a brief cameo as a chef — to closely study its world-class cooks in their element. “When I first read the script with Hùng, we planned for the first cooking scene to have very contemplative shots — wides, close-ups,” he says. “But when we went to Pierre’s restaurant, I brought my camera to shoot how they prepped their meals and was amazed at all these little things happening simultaneously. We soon realized that if we [went with our original plan], we would have a lot of quick shots and cuts and we would miss the whole point, which is the making of the food. So, we said, ‘We’ve got it all wrong. We need the cooking to feel like an action movie, always in movement.’”

Hùng had concerns, however, about the potential for Steadicam moves to feel too smooth to convincingly convey this sense of hustle and bustle. “I told him, ‘Steadicam is not the same as, say, handheld, so you have to choose’ — and he said, ‘No, I want both,’” Ricquebourg recalls with a laugh. To grant this wish, the cinematographer worked closely with Berthellot to bring a balance of elegance and urgency to their coverage of the kitchen, by punctuating their fluid navigation of the space with sharp-yet-precise push-ins on the action’s various high points. “Sometimes, I would [physically guide] Florian to move in faster, because we really needed to hit every spot at the right time; all the meals seen in the movie are real, and I knew the cooking time so well. But at a certain point, I didn’t need to [guide] him anymore — I’d just talk to him. We had to be really calculating about when we’d push in on each part of the process. And we only had a few minutes to shoot before each meal would expire. After that, the magic disappears.”

Cooking Glass

All of the film’s cooking choreography was shot with one lens: a 35mm Leitz Summilux-C, which, Ricquebourg says, “allowed us to feel each movement, while at the same time keeping that movement very discreet. We also needed to be able to start parts of the cooking process from a very wide shot and move into a close-up, and the Summilux-C allowed us to be very macro without applying any close-up attachment. So, we could go almost inside the oven when the scene called for it. It’s a very versatile lens; it’s close to the human gaze, but slightly wider, without the feeling of a wide angle, and without any deformation. And it’s between a short and long lens, so we could do medium shots [as well].”

The cinematographer also prized the Summilux-C for its “sharpness and precision,” as well as for “the volume it gives to the image and to faces,” and ultimately persuaded Hùng to use it for the majority of the production. (Minor exceptions were when one zoom lens was used — an Angénieux Optimo 24-290mm — for some exterior shots.) “Something I learned from a lot of other directors I’ve worked with,” he notes, “is that when you use one lens most of the time, the editing is so smooth, gentle and delicate. So, it’s really something I push the director to do.”

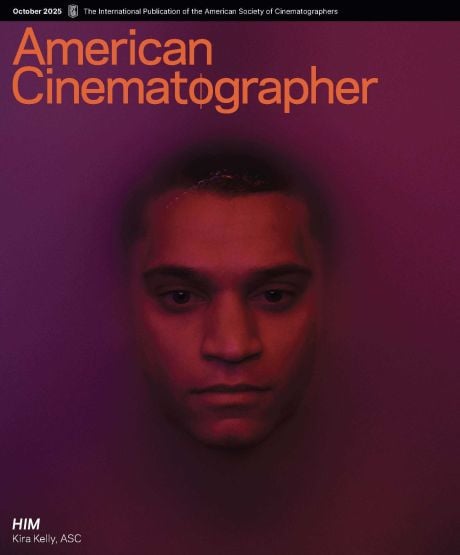

Black Night

The optics were paired with the Sony Venice, which served as the production’s sole camera. “Hùng and I really liked the feeling of the Venice — the precision of the colors and texture,” Ricquebourg says. “For most daytime scenes, we used it at 500 ISO, because I wanted the sensor to be full of light.”

Nighttime material was often shot at 500 ISO as well, but occasionally, for night exteriors that required more lighting fixtures, the cinematographer opted to shoot at 250, “so I could preserve the black,” he says. “We wanted to shoot at a stop of 4 or 5.6, which sometimes necessitated a lot of lights. I love to have black that I can model in postproduction — I don’t want a zero flat signal on the low end — and I knew that our black would be smoother and have more volume if we put a lot of light into it.” He quips, “I wanted to be able to see a black cat in the darkness.”

Blue Moonlight

In one such night scene, Eugénie and Dodin share cheese and tea under the trees beside a moonlit lake, where their talk of the prodigious Pauline’s potential to become a gourmand soon gives way to another of Dodin’s unrequited marriage proposals.

Hùng made clear to Ricquebourg that this scene would need a restive and romantic feeling to contrast with the cooking showcase that precedes it. To achieve this, the crew first considered shooting the scene in very low light and allowing for little to no color in its palette. But Ricquebourg instead opted for a lighting scheme that would cast the characters’ tête-á-tête against the hues of nocturnal spring.

The crew raised an Airstar spherical balloon containing two 1.2K HMI lamps and four 650-watt tungsten lamps. Harnack notes that “we chose to include the HMIs because the green of the leaves, which had just opened up in the springtime, stood out better.” Ricquebourg adds that the HMIs also “gave us enough power to bring up the bluish night sky.”

The filmmakers additionally placed small Swiss book lights — each comprised of one Creamsource Vortex8 LED, and each diffused with an 8'x8' Magic Cloth — in front of the actors, which Ricquebourg says helped add feeling and texture. “The rest of the scene’s color came from the reflections on the lake — the very small, very green grass on the surface of the water,” he notes. “When we turned on the lights, the blue mixed with the green to create a cyan atmosphere, which was great for the feeling we wanted.”

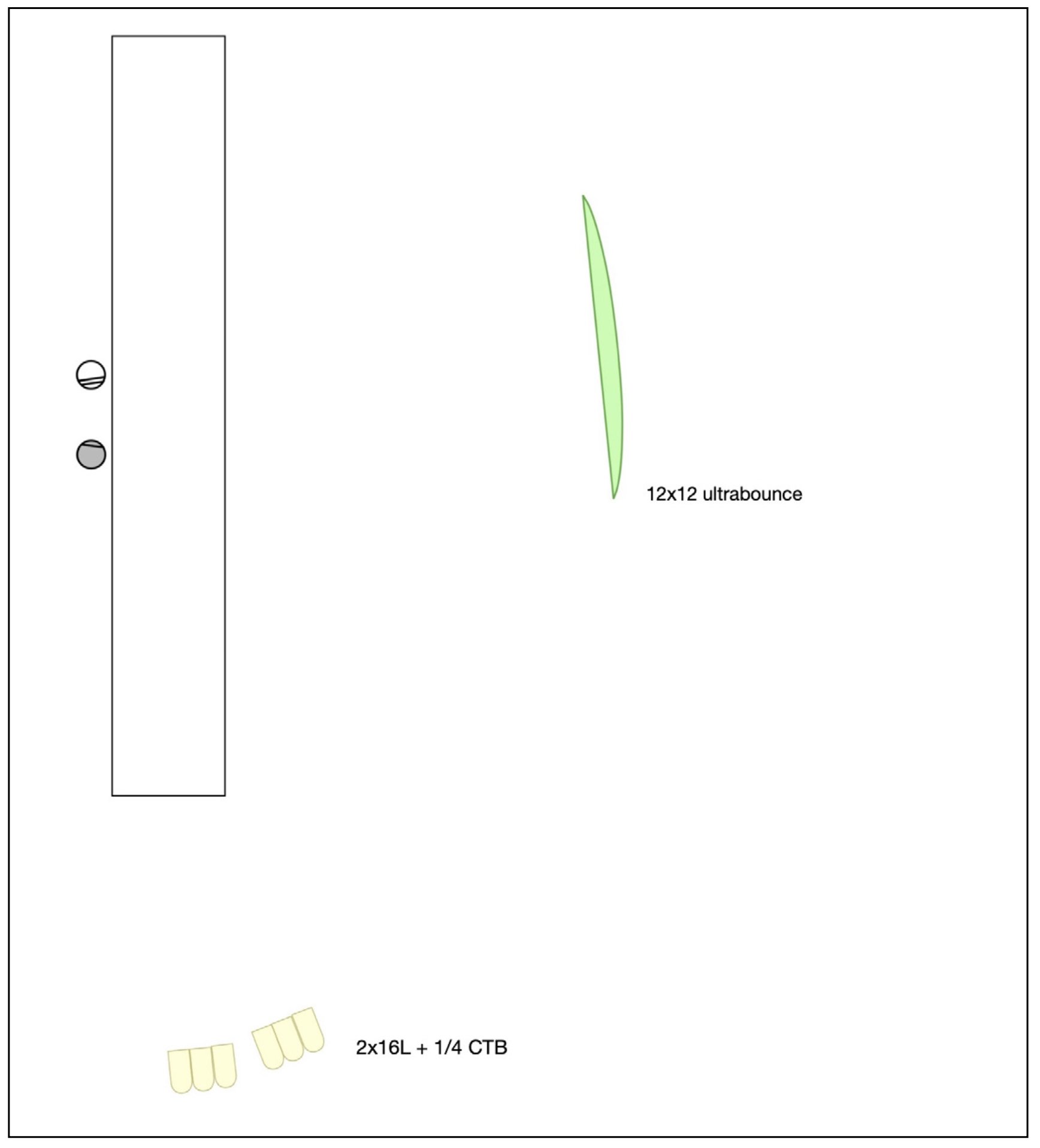

Summer of Love

A later scene, set under the summer-afternoon sun, finds Eugénie and Dodin at the same lakeside spot — this time joined by friends gathered around a long table for lunch, where Dodin announces to the group that Eugénie has at last accepted his hand in marriage. Ricquebourg says he sought to give this celebratory moment “a picturesque feeling, like a Renoir painting. Again, you feel the power of the sun, but in a way that’s not realistic. We used our lights to create this feeling that what’s happening in the scene almost isn’t possible.”

The setup for this dreamlike atmosphere (see diagram below) included two 16K Dino lights — positioned at the left-side end of the table — the first of which was diffused through silk, and the second of which served as a direct source. A 12'x12' Ultrabounce, placed on the side of the table opposite Binoche and Magimel, “helped bounce our natural light, to make the image very soft, and so we would feel the reflection from the sun and the characters wouldn’t look too ‘covered,’” the cinematographer notes. “And I frequently used muslin, because I find that its texture is more warm and round for the actors’ faces and skin tones.”

Ricquebourg’s sparing use of the Optimo 24-290mm zoom came into play when filming the scene that directly follows: a languorous tracking shot of the newly engaged pair walking and talking through a nearby meadow. For the lighting of this long take, however, “I did absolutely nothing,” he admits with a laugh. “This was the last shot of Juliette we did on that day, and it was not in the script. Juliette and Benoît have their own backstory — the two actors were a couple about 20 years ago. So, Hùng asked them, ‘Do you want to kiss each other?’ — and they said, ‘Okay, we’ll do it.’ We did the shot in maybe three takes, and there was some darkness coming from the woods but at the same time, some sparkles of light coming from the trees. I have to confess: The natural light was already perfect.”

Panning Time and Space

While Eugénie and Dodin walk through the sun-kissed field, they share their fondness for each of the four seasons — and these musings are heard once more in voice-over that accompanies the film’s closing shot. This final scene — which takes place after a terrible tragedy — is set in motion when Dodin urges Pauline, whom he has now taken under his wing, to join him as he prepares to meet another promising young cook. Following their departure from the house, the camera remains fixed in the center of the kitchen, then slowly pans 360 degrees through the space as Eugénie and Dodin’s dialogue enters the sound mix. As the pan progresses, a series of lighting changes conveys the passage of time, underscoring the couple’s reflections on the life they built together.

“This is a day-to-day story about everyday life — about a couple who work together and love one another. So, we needed to capture the mood of the sun as it moves throughout the day.”

“On the morning we shot that scene, Hùng told me, ‘I want all the light to change, and I want all of the seasons — please prepare for that, I’ll be back in an hour,’” Ricquebourg recalls with a laugh. “It was really hard, but at the same time, really nice to do it all on set. I was on the manual cranks for the Mo-Sys remote head to turn the camera — which was on a straight dolly track — in the center of the room. Hùng is sometimes a very old-fashioned director, so he loves to work with tracks, and as a DP, I do as well. Shooting on the track gives you the feeling that the camera is strong and firmly on the ground, as opposed to Steadicam, where everything seems to be smooth.”

Gaffer Harnack used a DMX lighting console to cue each timed lighting change as the pan was executed. Four 16K Dino lights were used outside, rigged to articulated lifts and Long Johns. Providing further illumination were a Maxi Brute aimed through the windows and door; two Astera Titan Tubes on the floor bouncing upward; eight Rosco DMG Mix LED fixtures wrapped in unbleached muslin, which served as top light; and two Arri L5s bounced into cardboard outside two windows located high up toward the ceiling. Other fixtures included two bounced 9K HMIs for ambience, one 9K Maxi Brute to illuminate the stairs and another in a side room, “and then a couple of PARs and SkyPanel S360s,” notes Harnack.

“We started with bluish lighting, and then we dimmed the Dino lights, and the mix of the two started to be a little bit purple — which, for me, was like the sun rising,” Ricquebourg continues. “Then, when we pushed all the fixtures to 100 kilos of light, we had the feeling of the summer sun.” Ricquebourg believes this epilogue of elapsing time honors the spirit of the film’s original French title: La Passion de Dodin Bouffant. “Hùng told me that ‘the passion’ is whatever still remains after you seem to have lost everything,” he says. “For Dodin, what remains is his love of cooking. And when you suffer a terrible loss or you’re very depressed — well, the sun still rises anyway. That’s the way we worked: ‘Can we bring beauty even into the worst conditions?’

“Prepping the last sequence taught me something really beautiful,” he continues. “I remember telling Hùng, ‘This is interesting: Our main character is getting old, and Pauline is young — she’s the new cook!’ And he said, ‘Leave it to the theoreticians to theorize. Don’t think — just feel.’ To be a cinematographer is to light something just the way you feel. In poetry, you have to write words that, together, create certain feelings. And it’s the same with light.”

You'll find further discussion about the film's final color work here.

Tech Specs:

1.85:1

Camera | Sony Venice

Lenses | Leitz Summilux-C, Angénieux Optimo

Lighting Spotlight | Hidden Ring, Hidden Fixtures

Among the greatest challenges for Jonathan Ricquebourg, AFC and

gaffer Georges Harnack during production on The Taste of Things was lighting what the cinematographer refers to as “the engagement room” — a candlelit dining chamber where Dodin serves Eugénie a medley of inspired dishes and, for dessert, a poached pear, whose elegant presentation cleverly conceals a ring for her to discover as she eats.

The walls in the room used for this interior shoot were decked with large mirrors, and since the filming site was part of a historic location — the Château de Raguin in western France — the crew was prohibited from removing or covering them, or from hanging anything on the ceiling, or using warm lights that could damage the paintings. To work around this problem, the crew hid various lighting fixtures used for the scene — including two DMG Dash LEDs, one hidden behind a table and another behind a piece of furniture. A few Astera Titan Tubes “were rigged outside to give the windows some life,” Harnack says. “But we used more inside, close to the windows, behind furniture and on the ground, just to light the wall and provide a backdrop for the characters to stand out.

“It was really hard to get light on the right spots for the characters, because we did a lot of Steadicam and there were mirrors everywhere,” Harnack continues. “So, we decided to light the set in prep and then see what could be done for the characters. We also had a lighting technician with a piece of unbleached cardboard following the Steadicam operator.”

A Source Four on the floor was aimed at the ceiling, “which was brown, so we threw some cold light to get a bounce that wasn’t too warm,” Harnack says. A paper lantern, fitted with an Astera Nyx bulb, was mounted on a Menace Arm to help light Binoche from overhead.

A K5600 Joker 300 LED provided additional spotlight from the ceiling, and Harnack came to regard it as “our best friend, because it’s lightweight and we could always manage to hide it somewhere on the set. It’s a great spotlight, because it has clean cuts and it’s super-light to rig. We used it to bounce light whenever we couldn’t rig fixtures,[whether due to the rules and regulations of the castle], or because they would be in the frame. For this scene, the Joker 300 was basically our solution for getting some light in the center of the set — where Dodin walks and talks, and where there was no furniture to hide any other lights. A balloon would have been too big.”

Although the warmth from the candlelight that surrounds Eugénie’s dinner table is one of the scene’s defining features, the cinematographer stresses that “the candles were just cosmetic.” Rather than motivate the lighting angles, Harnack says that “the candles were a part of the construction of the frame — they make everything shine in the background, which is just wonderful — but they’re not really the light.”

Ricquebourg notes that he and the crew “first prepared the background of the proposal scene without any actors” — an approach that sharply contrasted with his work on the 2016 historical drama The Death of Louis XIV. “When I worked with [director] Albert Serra on that film about seven years ago, he told me, ‘What I want is for the light to start from the face of the actor and then go to the set.’ And that was the exact opposite of what I did on this movie: For the engagement room, I started by lighting the set only, and then had the actors arrive inside that light. And when you work with actors like Juliette and Benoît, they understand where they should go according to where the light is.”

— Max Weinstein