In the Shadows on The Terminal List

Armando Salas, ASC captures a low-light narrative for this Amazon Prime Video series.

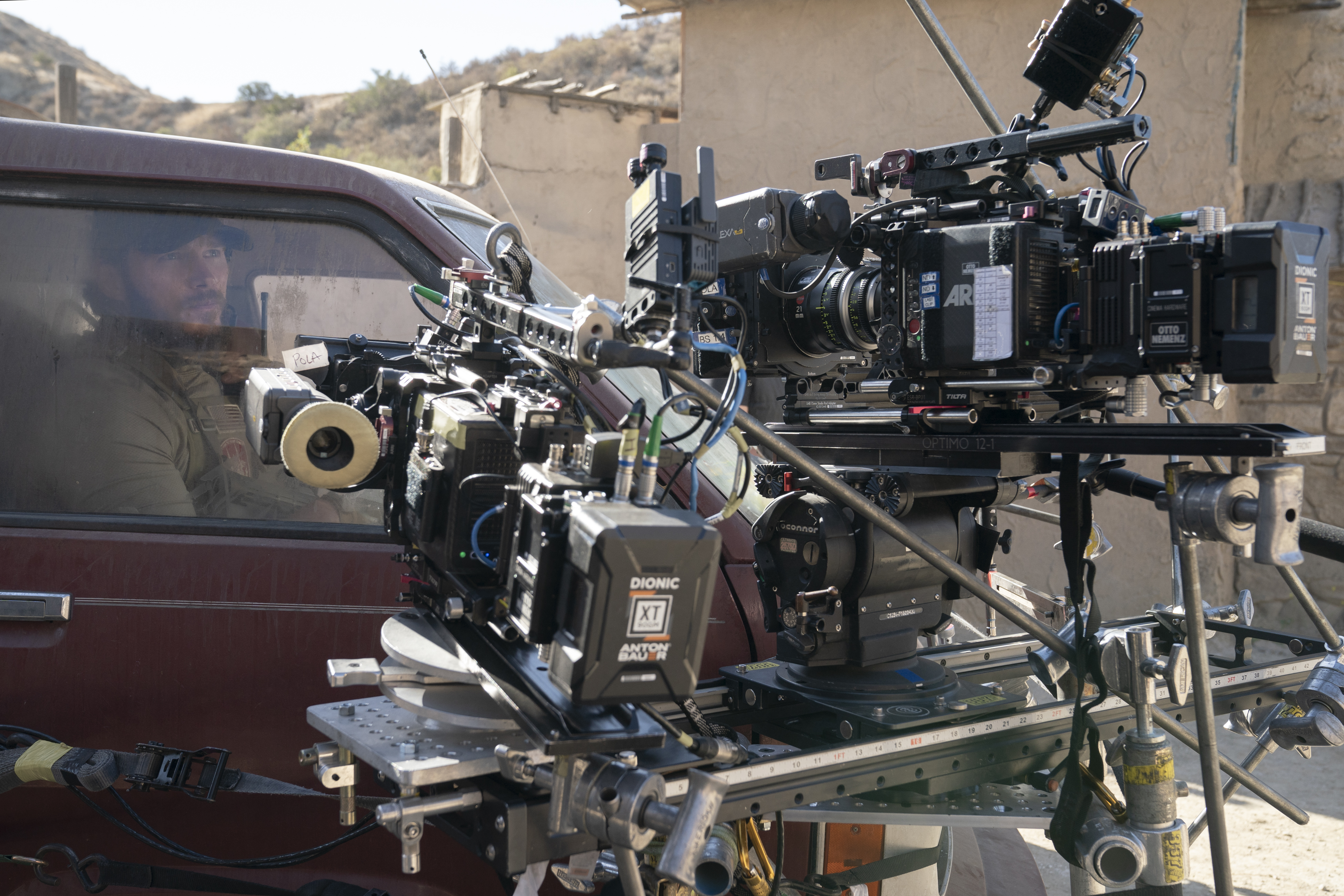

Photos by Justin Lubin, Courtesy of Amazon Prime Video.

ASC member Armando Salas’ use of carefully illuminated dark visuals on The Terminal List goes far to express the action series’ themes of paranoia, betrayal and high-level corruption. Key to the success of his techniques was the imperative that light introduced into a dark location must be motivated. “It has to be justified by the setting, the dramatic intent and the circumstances within a scene, so that it feels organic to the audience,” Salas says. “We wanted to be able to see enough to understand what’s happening. We didn’t want the audience to be a step behind — or for the darkness to go muddy, because then you lose a sense of focus. It was about finding the justification for the light source. We discussed how each sequence would look and feel as we chose locations, and that informed the strategy for lighting.

The Amazon Prime Video series — which is based on a Jack Carr novel — follows wounded, revenge-minded Navy SEAL Commander James Reece (Chris Pratt), who is intent on uncovering the conspiracy he believes is behind the decimation of his team. He operates in the shadows and often confronts his adversaries at night. The visual style created a challenge for the Cuban-born cinematographer and his collaborators — including directors Antoine Fuqua, M.J. Bassett, Tucker Gates and Sylvain White — as well as for Ellen Kuras, ASC and Frederick E.O. Toye, who both directed alongside cinematographer Evans Brown.

AC spoke with Salas, Fuqua (see below) and Kuras (also below) about their work in achieving the production’s low-light motif.

Lighting the Tunnel

The dark tone of the series is first established in a pivotal action scene in the pilot episode, set in Syria and directed by Fuqua. After Reece briefs his men on their mission, they land on a beach in the dark of night and enter a sewer-tunnel system that’s supposed to lead to their target. The operation ends in disaster — an ambush, Reece believes — and a trail of casualties.

The tunnel set for the seminal sequence was constructed in the Blue Sky Tank at Paramount Studios and allowed the actors to trudge through shin-deep water:

Introducing light into what would otherwise be a pitch-black area, a SEAL breacher uses a thermal Breachpen to cut through a metal grate impeding their path. “The torch produces blindingly bright yellow-orange light,” says Salas of this specialized tool provided by props and special effects. “We spent a good amount of time on that beat. We gave each of our heroes a moment with their night-vision goggles up and that flickering light on their faces before they get swallowed by the darkness of the sewer tunnels. We tested [the torch] ahead of time to ensure that the color and quality of light gave us the ethereal effect we were looking for.” The light from the Breachpen was augmented with a flicker effect provided by Arri SkyPanels with the aid of lighting programmer Jeffrey Horbachewski. “Then, as the light of the breaching torch fades, smoke fills the tunnel,” Salas adds. “They flip on their goggles and essentially disappear into darkness.”

Collaboration on the set design was key to devising lighting solutions. Salas and gaffer Cooper Donaldson approached art directors Robert Joseph and Mark Larkin (working under production designer Warren Alan Young) about building in portholes on either side of each brick archway that connected the tunnel sections. Over those portholes, they rigged Kino Flo FreeStyle 31 LED panels to provide a non-defined light source.

“This way, we had control over how much light was scraping the tunnel walls — how much ‘toppy’ back- and front-light we would have in any one section,” Salas says. “Then it was about carefully controlling how much fog was in there to not give away the sources.”

The tunnels led to a 70'x50' area — dubbed “the crypt” — which featured low arched vaulted ceilings. In this section, the art department included 4'x4' ceiling grates — ostensibly leading up to the street — which dripped water through a dressing of trapped sewage. The crew shined two Kino Flo Celeb 450s through each grate, pointing in various directions, to supply room tone. “You want to at least show our heroes silhouetted in an environment,” Donaldson notes. “There is so much going on, and you wouldn’t want to see only a couple of flashlights through the haze. We were trying to get a very dark overall base layer, which Armando felt the Kino Flo LEDs would give us if dimmed down to 10 percent — or even 1 percent. The FreeStyles allowed us to dial in color very accurately, even though we were using them at the bottom end of the dimming capabilities.”

Flashes and Flashlights

At the point when the SEALs realize the crypt is rigged to explode, flashlights attached to their rifles serve as a primary lighting source. “In this part of the sequence,” Salas says, “we lit the actors with more shape — versus just texture and mood — and they pull off their night-vision goggles so we can once again see their faces.”

The camera crew took color-temperature readings of the flashlights and then gelled them accordingly. “Those consumer products can run up to 10,000K and create more of an undesired eerie, sci-fi look,” Donaldson says. “So, we would put some 1/2 Straw on them. Sometimes they would be too bright, so we would also have ND .3 or ND .6 filters ready to go.”

Suddenly, the SEALs are engaged by enemy fire and the tunnels become alight with muzzle flashes. The crew used Titan tubes in pixel mode to create machine-gun and fire effects, running upwards of 16 fixtures at a time. The battery-powered units were particularly helpful in minimizing cabling in the water-filled set.

As the melee escalates and the eruptions of light become increasingly chaotic, an explosion is detonated. Reece wakes up concussed and disoriented, and in the middle of a firefight — engulfed in smoke and surrounded by fire and debris. “We photographed his close-ups and his POVs at 48 fps to slow down some of the scarring imagery that will haunt him later,” Salas says. “We also photographed a key moment that led to the explosion in extreme slow motion, though that perspective is only used later as Reece is trying to remember the events that led to the death of his men. The initial sequence is quick and messy within the chaos of a firefight. The memory of the event keeps changing and evolving, so we photographed the same moment multiple ways with different characters using a Phantom 4K camera at 600 fps.

“Lighting for that exposure required quite a bit of firepower within the submerged crypt,” the cinematographer continues. “We had a game plan for how to change the lighting over; Cooper and his team executed it very quickly while keeping everyone safe. We created a wall of Arri 360 SkyPanels on one side for a base exposure, which key grip Bobby Thomas teased off the ceilings. To help focus the eye, we bounced hard light off the water. At 600 fps, the ripples of light were practically frozen, which added a hint of surrealism, almost cutting out the subject from the background. The combination of frame rate and lighting created a visual representation of our protagonist trying to make sense of his unreliable memories.

Confrontation by Firelight

Salas points to another instance of his work with low-light cinematography — in Episode 3 (directed by Bassett), when Reece sneaks into the vacation house of Saul Agnon (Sean Gunn), lackey to mogul Steve Horn (Jai Courtney), whose interests extend into the military sector. To avoid suspicion, Reece raises the volume on the classical music playing in the house to drown out his prisoner’s cries and turns off all the lights, with light only emitting from the fireplace. Says Salas, “The scene essentially takes place in front of the fireplace with the characters in silhouette — in half-light and quarter-light — but there’s always a twinkle in their eyes. There’s always the ability to read their performances, even though it’s a very dark scene.”

The cinematographer supplemented the practical firelight with FreeStyle 31 panels fitted with DoPChoice Snapbags and Snapgrids. The crew also lined a soffit above the fireplace with Astera Titan and Helio tubes pointing up to the ceiling to provide ambient fill. A flicker effect that further amplified the firelight was created with Titan tubes and LiteGear LiteMat Spectrum fixtures.

“Many of these smaller LED products are really useful for locations like that, because they are good to tuck up in places,” says Donaldson. “Also, we were trying to get all our lights on wireless receivers and batteries to have freedom of movement for the camera, without seeing stingers and DMX cables. We controlled using CRMX wireless technology.”

Set of Tools

Salas says the Arri Alexa Mini, which recorded in XQ UHD, is very sensitive and performs well in low-light situations. “Stefan Sonnenfeld and I spent several hours creating and fine-tuning the show LUTs so that I felt very confident about our digital negative. We ended up with a really filmic LUT, not overly aggressive, and I got comfortable with what we could see in the shadows. We lit for those nuances down in the toe of the curve.”

The filmmakers shot with Leitz Summilux-C and Summicron-C primes, which the cinematographer characterizes as “modern and clean without being harsh and ultra-sharp.” They also used a Fujinon Premier 75-400mm T3.8 zoom for surveillance-style shots and a detuned 28mm Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime with a diopter for extreme close-ups of Reece when his mental state is suffering.

The filmmakers usually shot dark interiors between T2 and T2.8, unless they wanted to isolate a moment or have more fall-off for a portrait-style image, in which case they would shoot wide open. Says Salas, “My focus puller Neil Chartier is amazing in dealing with shallow focus on complex moves that usually started or ended with the camera very close to the actors.”

The narrative’s overarching theme was one of the production’s key draws for Salas. “The audience is rooting for the insurgent — the guy who’s unjustly lost everything and has the means to seek revenge,” he says. “What really drew me to this project is the motif of our main character possibly getting lost in the darkness.”

There were two reasons why director Antoine Fuqua wanted to collaborate with cinematographer Armando Salas, ASC on the pilot for The Terminal List. One was the recommendation of showrunner David DiGilio, who had worked with Salas on the CBS historical drama Strange Angel. The other was the cinematographer’s work on Ozark.

“Ozark is dark, and I was trying to find a cinematographer who understood minimum lighting in dark places,” Fuqua says. “We didn’t want the opening sequence of The Terminal List to have a tunnel that was just all black. It was complicated because Armando had to hide the lights. You believe these [SEALs] are in a dark place with no light, but there’s just enough that you can see them.”

The director adds that the tunnel scene was shot darker than ultimately presented. “You want to take the audience to what the tunnel would really feel like, but you want to try to distinguish which guy is which and understand how they operate,” he says. “Colorist [and ASC associate] Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3 [used selective power windows and tracking mattes to help focus the eye.]”

Fuqua, who directed the pilot and stayed on as executive producer for all eight episodes, notes that he and Salas worked together to finalize the show’s lookbook. “I pulled images and then manipulated them,” the director says. “It could have been something from Black Hawk Down [2001, shot by Sławomir Idziak] or war pictures where it was nearly black-and-white, like in our tunnel — although we needed to see the texture of things. I made sure the visual books went to everybody. Once I got Armando’s input, we got those to the producers, the other cinematographer [Evans Brown] and all the directors involved to try to keep some consistency.”

For the sewer-tunnel sequence, the filmmakers employed the series’ main camera package of three Arri Alexa Minis — as well as other units for the soldiers’ night-vision perspectives: On Pratt, they mounted a GoPro Hero7 Black converted to full-spectrum by Kolari Vision, while the other SEALs were outfitted with helmet- and shoulder-mounted Mohoc IR military cameras. For night-vision inserts and specific story beats, they also converted a Red Gemini (set to 3,200 ISO) to full-spectrum — “visible light plus IR,” Salas says.

On the pilot, Kirk Gardner served as A-camera/Steadicam operator and Joshua Harrison served on B-camera. Harrison then transitioned to A-camera Steadicam operator for the rest of the season.

Regarding aspect ratio, Salas opted for the traditional 2.35:1 widescreen. “Given that most streamers are now cropping to 2:1 or 2.25:1, the standardization for episodic is a bit out the window,” he says. “We chose 2.35:1 — with custom frame lines and framing charts for that ratio — for widescreen, as 2.39:1 felt a bit too wide.”

The darkness established in the tunnel sequence in Episode 1 of The Terminal List carries over into Episode 2 — even to locations that are lit darker than they would likely be in real life, including a military office, the house of Commander Reece (Chris Pratt), and the home of his former SEAL buddy Ben (Taylor Kitsch).

Director and Society member Ellen Kuras was able to watch dailies from the pilot as she prepped Episode 2 with director of photography Evans Brown. “I told Evans I wanted to use light — or the absence of it — as a metaphor,” she says. “We should see the darkness that lurks in Reece’s mind in the lighting, and how he moves in and out of the shadows will also tell us what’s going on in his head. The lighting goes hand-in-hand with the meaning of the scenes.”

Following his disastrous mission in the Middle East, Reece senses a high-powered conspiracy closing in on him in the second episode. His concerns fall on deaf ears with his superiors, so he decides to take matters into his own hands.

Kuras told Brown that she wanted the audience to feel like they were with Reece — in his head — which was an especially interesting perspective, given the brain injury that might be clouding his judgment. Says Kuras, “This approach helped us decide how I would block the actors, where we were going to put the camera, and how it was going to move — whether we would do a moving master vs. a shot on a close-focus lens directly behind the character’s head.”

She praises Brown’s “fantastic eye,” and adds that “he was able to bring a real sense of drama, giving the episode more oblique framing and challenging what we would see in the frame.”

She credits both Evans and Salas for maintaining the series’ dark palette. “It’s operating in darkness, but you can see everything that’s happening,” she says. “It’s difficult to do because you need separation, otherwise things fall into the blackness and you can’t see what they are. To me, the most exciting kind of imagery is when there is a sense of mystery and the unknown, yet certain things stand out and there’s a sense of depth — even in the deep darkness.”

She would sometimes ask Brown to throw more light on a scene. “We needed that separation,” she says. “I wanted to make sure we could see or feel what’s happening. And that’s me as a DP saying that — and if a DP says it might be playing around too much in the dark, that’s pretty dark!”

Fuqua and Salas mapped out a muted color palette for the series, which drew from military influence — primarily black, gray, khaki green and brown. “Once the story reaches San Francisco, we introduced quite a bit more blue for that storyline,” says Salas. Red was nearly completely eliminated, with a notable exception being a cape that Pratt’s character’s daughter wears in a key recurring memory. The cinematographer adds that “red became a color clue for the audience when our protagonist is having trouble distinguishing memories from reality, which [we] referred to as ‘conflation.’ As the conflations continue throughout the season, we added more red elements.”

2.35:1

Cameras: Arri Alexa Mini, Red Gemini, Phantom Flex4K, Mohoc IR, GoPro Hero7 Black

Lenses: Leitz Summilux-C and Summicron-C, Fujinon Premier zoom, Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime