The Thing From Another World

Behind the scenes with one of the first “alien invasion” films of the 1950s, and certainly one of the best.

“Who Goes There?” Is a wonderfully inventive, absolutely terrifying yarn. It made its debut bearing the byline "Don A. Stuart" in the August 1938 issue of the Street & Smith pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction. Stuart was a nom de plume of the magazine's editor, John W. Campbell Jr. (His wife's maiden name was Donna Stuart).

The story — which has since been imitated endlessly — tells of Antarctic expeditioners who find an alien which has been frozen in the ice for 20 million years. The creature is four feet tall, weighs 85 pounds, has wriggling blue hair, tentacles, three angry red eyes and green blood. When thawed out it comes to life and begins to absorb other living things — sled dogs, livestock and men. The scientists kill the thing but soon realize it has invaded several of their number, rapidly taking control not only of their bodies but their minds and personalities as well. By multiplying this way, the alien could eventually take over the entire planet. Fortunately, the surviving scientists find ways of identifying the possessed humans and destroying them.

As a director and sometimes producer, Howard Hawks made important contributions to a more naturalistic acting style in a wide variety of movies. These included some of the top-ranking comedies (His Girl Friday), gangster stories (Scarface), Westerns (Red River), prison dramas (The Criminal Code), and war pictures (The Dawn Patrol); but he hardly seemed the type to initiate a flight of fancy a la Campbell. Hawks, however, had taken note of the phenomenal growth of science-fiction magazines following World War II, read several, and decided to buy the rights to "Who Goes There?" for his Winchester Pictures Corporation. (Winchester was Hawks' middle name).

In a press release, Hawks stated, "The advent of this type of film opens a vast story market. Because the subject matter is involved with that which is unknown, science-fiction stories permit the use of new and different plot structures in the writing of screenplays. Clever writing enables one to hold interest by the presentation of a scientific background which adds a lot of authenticity to the story as it progresses.

“The science-fiction film is based on that which is unknown, but given credibility by the use of scientific facts which parallel that which the viewer is asked to believe.”

— Howard Hawks

"It is important that we don't confuse the Frankenstein-type of film with the science-fiction picture," Hawks continued. "The first film is an out-and-out horror thriller based on that which is impossible. The science-fiction film is based on that which is unknown, but given credibility by the use of scientific facts which parallel that which the viewer is asked to believe. Forgetting that almost every Hollywood studio has at least one science-fiction story on its production agenda, one need only check the growing popularity of the science-fiction magazines to learn of the ever-increasing demand for this type of literature."

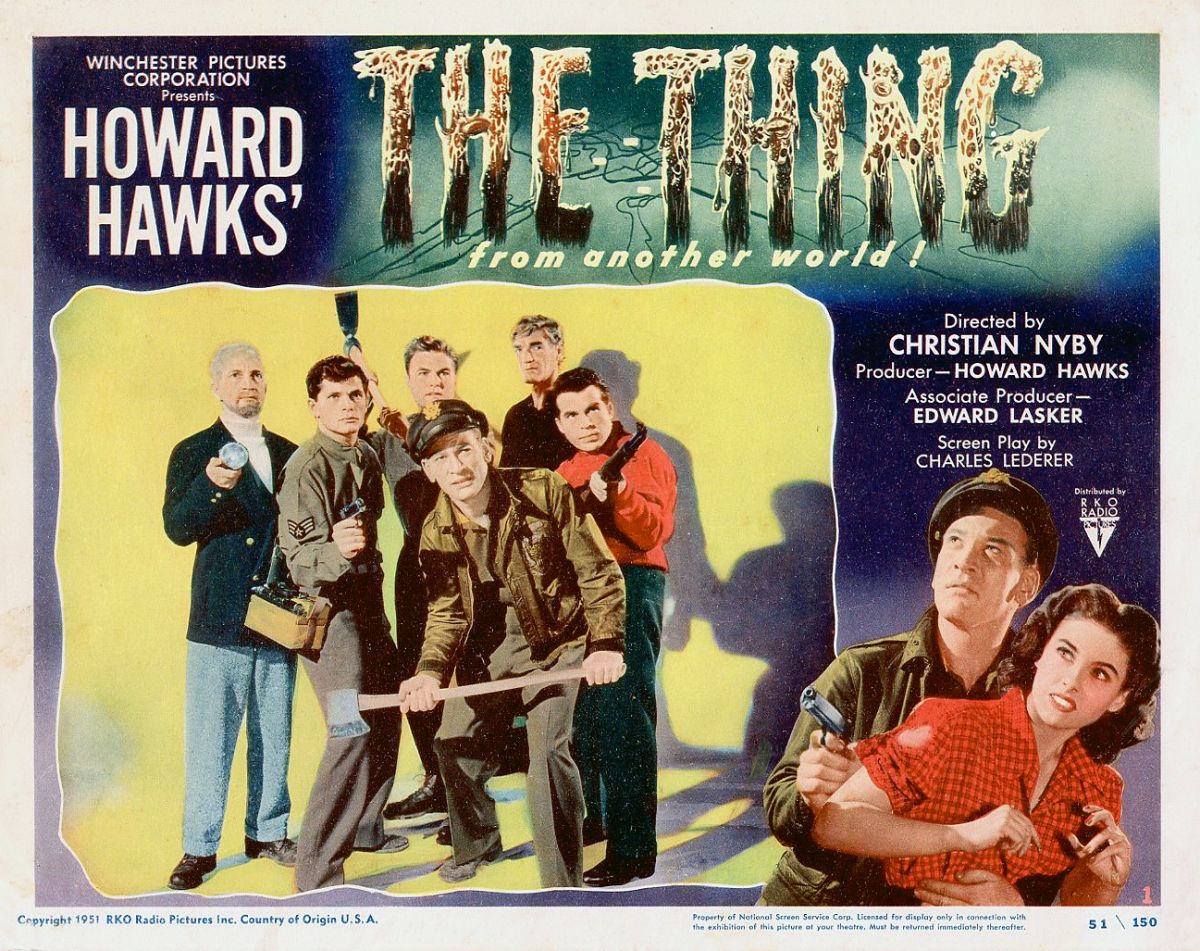

Hawks' picture was The Thing from Another World, which appeared in April of 1951 in the midst of a welter of science-fiction pictures. Flying saucers and alien invaders became staples of numerous films of the 1950s. Many are awful, some are tolerable, a few are good. The Thing is great. This masterwork of the genre was the first of its particular kind of science-fiction film — the depiction of a dangerous alien at large on earth — managing by a few days to reach the theaters ahead of a much lesser film with a similar theme, The Man from Planet X. None of its imitators have succeeded in duplicating its adroit blend of old-fashioned horror, new-fangled science-fiction, he-man adventure and down-to-earth romance. Heaven knows, they've tried.

Curiously, Hawks never again showed any professional interest in science-fiction or macabre themes despite the fact that The Thing was highly successful and his prediction of a "vast story market" did indeed develop.

Hawks and his partner in Winchester, Edward Lasker, made a deal with RKO Radio Pictures to co-produce two large-budget pictures, The Thing and The Big Sky. The screenplay of the first was assigned to the versatile Charles Lederer, who had previously written such notable successes as Kiss of Death, Ride the Pink Horse, Slightly Dangerous and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Lederer and Hawks felt that Campbell's story would be too complex to put over as written, so they concocted a simpler plot line that differed considerably from the published novella. A half-dozen re-writes consistently distanced the concept from the original concept. The first draft retained a monster fairly similar to Campbell's description, but by time the script was ready to film the creature became a giant, hairless, humanoid vegetable which somewhat resembled Universal's Frankenstein monster. The location was changed from an unidentified research base in the frozen wastes of Antarctica to a United States Air Force base on the frozen wastes north of the Arctic Circle. The change from the South Pole to the North Pole was less radical than the jettisoning of the central concept of the novella: the ability of the alien to take over the bodies and personalities of others.

The Hawks-Lederer creature is referred to jokingly by the military personnel as a “monster from Mars.” Stronger and more swift than a man, utterly devoid of emotion, asexual, and completely merciless, the alien is driven by a compulsion to colonize earth with its own kind. It lives on animal blood; even its seedlings sprout only from blood-soaked soil. The group of airmen and scientists, forced to defend themselves against the lone alien, find him damnably hard to handle.

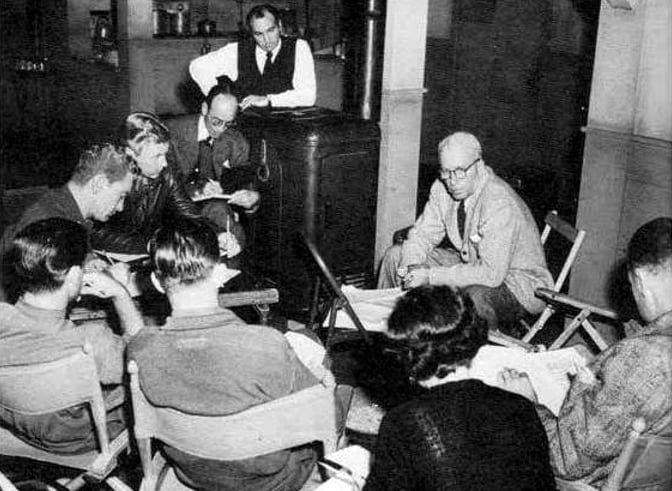

Once the scripting problems were worked out, Hawks gave the reins to Christian Nyby, a top-ranking film editor, as his first directorial effort. Nyby's later films proved him to be a versatile director of theatrical features as well as television drama and comedy. He had previously cut Hawks’ films To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep and Red River.

That The Thing is overtly in the style of Hawks is hardly surprising, for he was a strong-willed producer who was present at most first-unit shooting as well as much of the location work. The loose handling of dialogue, with realistic interruptions and overlaps, is done in the best Hawks manner. The pace is fast and smooth, punctuated with shocks and leavened with well-spaced romantic and comic diversions. A light touch is present at the very times it needs to be.

Hawks and Lasker planned to film much of the picture on location in Fairbanks and Nome, Alaska, where they counted on receiving government cooperation — including use of personnel and equipment at USAF bases. This was standard procedure in the making of pictures dealing with contemporary military activities. Their hopes were dashed when the following reply from the Pentagon, dated September 14, 1950, was forwarded from RKO's New York headquarters:

The script of Winchester Pictures' proposed production The Thing has been reviewed, and it is regretted that we will not be able to extend cooperation as the story revolves around flying saucers and their possible contents.

The Air Force has maintained the position for some time that there are no such objects as flying saucers and does not wish to be identified with any project that could be interpreted as perpetuating the myth of the flying saucer. Also, the Air Force seriously objects to any mention of Air Force personnel and equipment, or pictorial sequences representing Air Force personnel or equipment, being included in the film.

Providing your company plans to proceed on the production without Air Force cooperation, we request every consideration be given to the Air Force objection in the interest of maintaining goodwill and relations.

The Air Force has dispatched a wire to the Commander-in-Chief, Alaska Theater stating their objections.

Sincerely,

DONALD E. BARUCH

Chief, Motion Picture Sect. Pictorial Branch

The Air Force later relented to the extent of offering to approve the picture if the story was "presented as a dream." The studio and Hawks agreed that such a change was untenable. It was decided to risk Uncle Sam's displeasure and proceed without government approval, even though this meant finding different locations and obtaining the proper aircraft, equipment, uniforms and technical advice by other means.

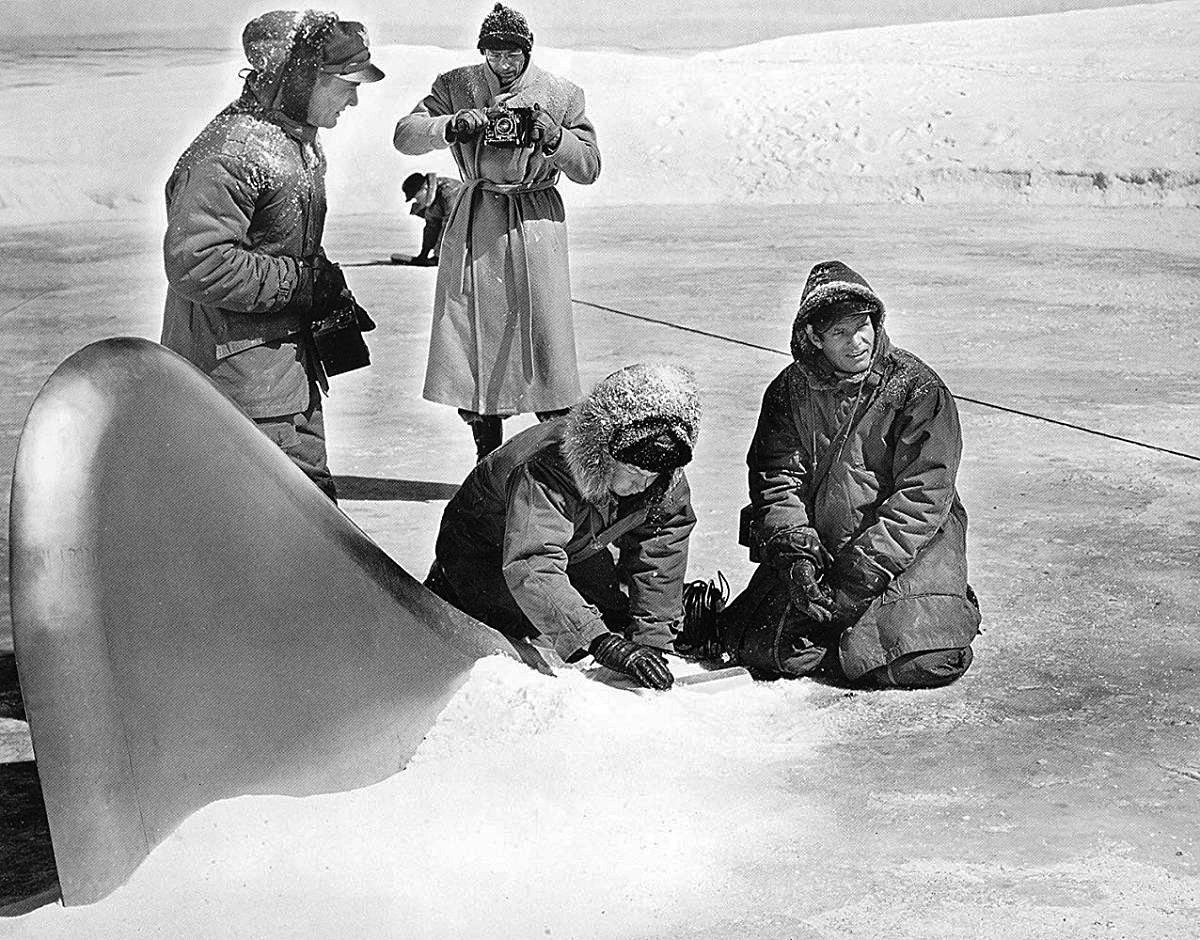

Even as the Air Force was stating its objections, a five-person crew under cinematographer Archie Stout, ASC had been in Alaska for a week, innocently shooting background plates. Another crew — under Harold E. Wellman, ASC — was working at Iverson Ranch, near Chatsworth, California, photographing the full-scale fire and explosion that destroys the flying saucer. Within a month, Russell Harlan, ASC was at the RKO Pathé lot in Culver City shooting tests of the players.

Harlan was contracted to be the director of photography on both RKO-Winchester productions. A rugged outdoorsman, Harlan first gained fame as a photographer of high-grade Westerns after serving as second cameraman for Stout. He shot around 60 of producer Harry Sherman's exquisitely photographed Hopalong Cassidy pictures as well as "specials" based on works by Zane Grey and other famous writers. He escaped Western "typecasting" in 1949 with the film noir classic Gun Crazy (Deadly is the Female), which broke some new ground photographically. His first collaboration with Hawks was the monumental Red River; yet to come were The Big Sky, Land of the Pharoahs, Rio Bravo, Hatari! and Man's Favorite Sport.

It was decided early that the picture would have a cast of good actors from radio and the stage, but no big-name players. This was announced as being Hawks' way to enhance the realism of the picture. It was a valid idea, but possibly less important than the fact that RKO refused to approve a budget that would include star salaries on a picture that already shaped up as one of the studio’s more expensive releases of the 1950-’51 season.

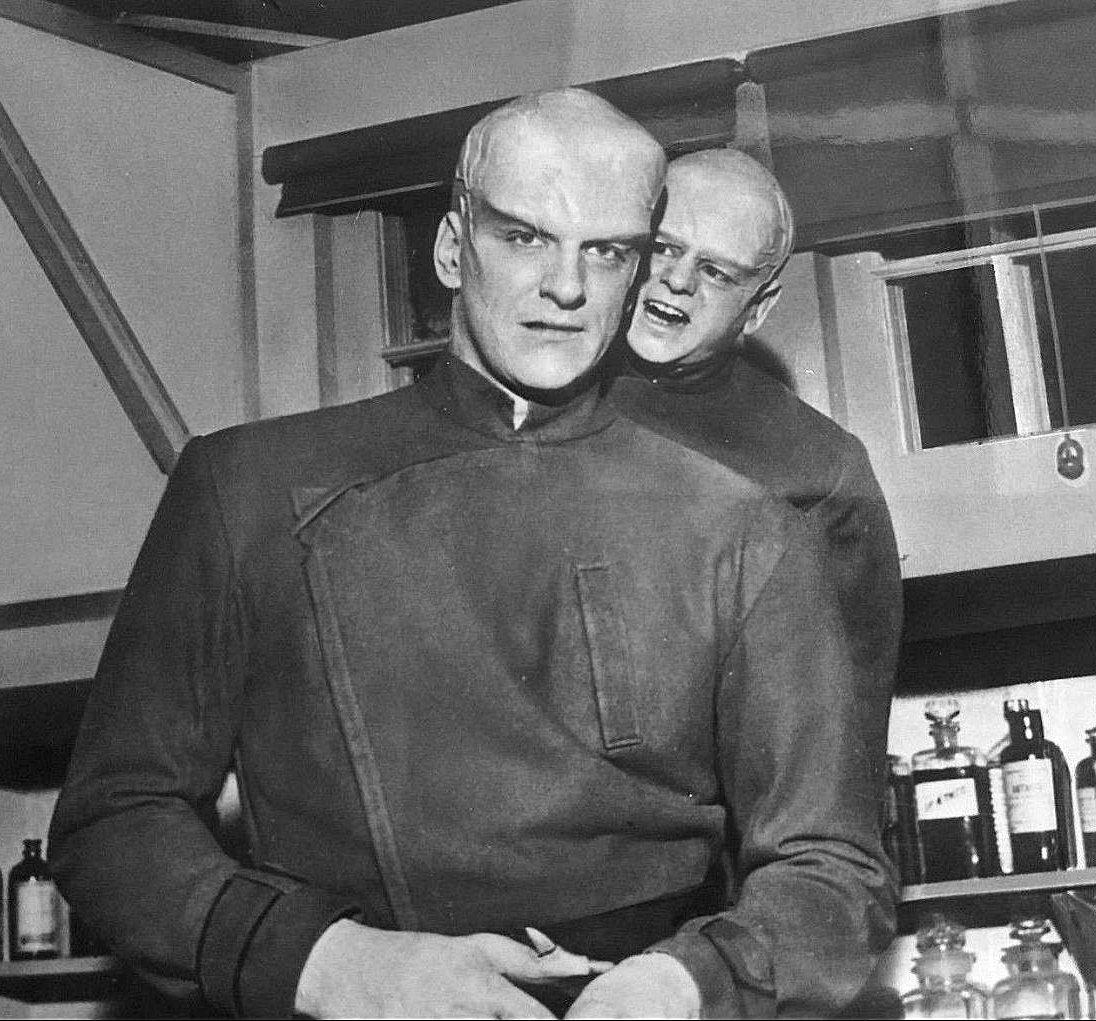

Although it has been said that James Arness was brought in to play the title character as a last-minute casting change, he actually was the first actor hired and received considerable advance publicity. Early in October, RKO allowed Lasker to hire the obscure young actor, who had played minor roles at the studio and larger parts in some independent productions. Arness was a handsome, 6', 7" blond giant who bore a strong resemblance in appearance and manner to John Wayne:

Arness received $750 per week with a four-week guarantee. He was also handed a $1,000 petty cash voucher in advance and a salary extension clause of eight days beyond the completion date as an inducement not to take any other jobs before the starting date of November 18. According to the budget submitted to RKO by Lasker, the arrangement was necessary because Arness had to be “available at all times for fitting his head and costumes... as it will take us some weeks to prepare the molds for his head, which then can not be used on any other actor."

During the preliminary stages of pre-production, Nicholas Volpe, a well-known Hollywood portrait artist, was brought in to make numerous concept sketches for the makeup of the alien. None of these fanciful ideas were used. A budget of $10,000 was set aside for makeup experimentation. Stuntmen Bob Morgan, Chuck Moreland and Sol Gorss took turns standing in for Arness while Lee Greenway tried to develop a monster that would meet Hawks' approval.

Several times each week, Greenway would bring a made-up stuntman to Hawks' Brentwood home, hoping for an okay. About two months elapsed before Arness actually went before the camera in the approved makeup and costume. For some reason, Arness, who would later achieve immense popularity as Marshal Dillon of the Gunsmoke television series (which ran an incredible 20 years on CBS and is still a popular syndicated show), was embarrassed by his work in The Thing and refused to discuss it in later years.

Hawks' theory proved sound that a cast of solid actors virtually unknown to moviegoers would lend more conviction to a fantastic story than would familiar Hollywood players. Hawks tested fashion model Margaret Sheridan for the feminine lead, Nikki Nicholson, after seeing her picture in Vogue — as had been the case with Lauren Bacall and Ella Raines in earlier years. She proved an excellent choice for a typical Hawks heroine — slim, pretty, a little tomboyish, likeable and self-reliant. Why her career never took flight, as had those of Bacall and Raines, is a puzzling question.

Ken Tobey, a ruggedly good-looking actor with considerable stage experience and minimal movie exposure, was cast in the male lead and gave a strong, realistic performance. Lanky Douglas Spencer, a former stand-in for Gary Cooper and Ray Milland who had spent a long time at Paramount without graduating beyond bit parts, was wisely cast as the irrepressable reporter, Ned Scott. John Dierkes, a tall, sepulcheral voiced former FBI man who had been sent to Hollywood as a technical advisor and decided to remain as an actor, was chosen to portray Dr. Chapman, the leading scientific voice in favor of destroying the alien. Dewey Martin, a young actor in whom Hawks sensed strong potential, was signed to a contract and put into a major role that was written in after the final script was okayed.

George Fenneman, Paul Frees, Sally Creighton and several others known for their voices as radio personalities but with faces relatively new to the screen, portrayed scientists and technicians. James Young, who played the co-pilot, was a New York disc jockey. Eduard Franz, Edmond Breon, Everett Glass and Norbert Schiller, all of whom appear as scientists, had long stage backgrounds. William Self, who acquits himself well as a corporal, was destined to quit the acting field and become an important executive and producer in network TV.

Robert Cornthwaite, who has the best character role in the film as a fanatical scientist in his mid-50s, was a young man in his early 20s in a fully convincing makeup. He was unrecognizableas the former Dr. Carrington in his later pictures without his “mad doctor" makeup.

While casting was under way, location scouts searched for a suitable stand-in for Alaska. They found it at Cut Bank, Montana. In December, Hawks, Nyby, 10 actors and 27 crew members flew to a windswept plain near Cut Bank to stage the sequence in which the flying saucer and its pilot are found frozen in ice. Meals for the company were furnished by the Glacier Hotel, where most of the personnel stayed while the remainder were billeted in private residences. Dog sleds and teams, manned in part by Eskimos, were acquired from the Sun Valley Operations branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. Two camera crews were used, one headed by Russ Harlan and the other by Harold Stine, ASC — who also shot the process background plates.

The desired snow was found in abundance, as it snowed nightly. Unfortunately, high winds blew the snow away each day before much work could be done. A tractor was used to clear out the circular area where the saucer had supposedly crashed and become entrapped under the surface. The tractor can be seen easily in one of the aerial shots of the picture. Because of the blowing snow it became necessary to photograph many of the saucer scenes again, this time in the San Fernando Valley. The ice was created by pouring photographic solution over the area and letting it crystallize in the sun. The actors, no more comfortable than they had been in the sub-zero weather at Cut Bank, sweltered in their Arctic gear.

Equally uncomfortable was the location utilized for certain indoor scenes at the base. To realistically portray the deadly cold that gripped the base after the Thing cut off the fuel supply, these scenes were filmed in an icehouse on Mesquite Street in Los Angeles. The breath of the actors vaporizes and the reactions to the bitter cold are realistic. Frank Capra used the deep-freeze studio when he made Lost Horizon 14 years earlier.

Lee Greenway's $10,000 experimental makeup budget had more than doubled by the time Hawks okayed the least complex design he had submitted. The design, rendered first in mortician's wax and then developed as a foam-rubber prosthetic, somewhat resembles makeup worn by Boris Karloff in the 1931 Frankenstein.

The domed and hairless skull was embellished with plastic veins through which colored water flowed as Arness breathed. The device covered his nose, upper cheeks, forehead and neck, and was attached with spirit gum. The entire head was covered in varying shades of green greasepaint.

The forearms and hands, which were designed with claw-like thorns on the knuckles and fingertips, were fashioned like gloves. With special shoes and the built-up skull, Arness stood over 7' tall. Despite his size and a painful limp (resulting from wounds received in the World War II landing at Anzio when he was in the U.S. Army infantry), Arness moves in a lithe, cat-like manner that adds menace to the character.

Greenway made several versions of the Thing's arm, which is tom off by sled dogs early in the film. For scenes in which the arm comes to life while being examined by the scientists, the hand was operated from inside by a woman reaching up through a hole in the table.

Although the appearance of the alien was changed considerably, it was decided to keep the alien's voice the way Campbell described it: as "a savage, mewing scream." This was achieved by slowing down and distorting tracks of cat cries.

Unforgettable is a sequence where in the Thing bursts into a dormitory and is doused with buckets of kerosene and set afire. After a terrific struggle it leaps through a window and runs away, still aflame. These scenes were filmed MOS on RKO's Stage 7 utilizing eight stuntmen, four cameramen, five electricians, two grips, two prop men, a cable man, six special effects men, one painter, two firemen and a doctor. No visitors were allowed during the several days necessary to stage the action. Arness, Spencer, Martin, Self and Nichols appear in the initial shots, then replaced by the stunt artists as soon as the fire effects began.

Tom Steele, a tall stuntman noted for his spectacular work in Republic and Universal serials, was assigned to double Arness. He was protected from the flames by asbestos covering. His head makeup was made of a fireproof plastic and he was able to breathe through tubes which ran from his nostrils to an opening in the chest. Although the scenes were choreographed intricately, two of the stuntmen received painful bums.

The destruction of the Thing by electricity was planned first as a straightforward mechanical effect supervised by Donald Steward. Electrical expert Kenneth Strickfaden, famed for his work in numerous movies including Frankenstein and The Mask of Fu Manchu, was brought in to provide electrical effects. Arness, Teddy Mangenes and Billy Curtis (a well-known dwarf actor) were all made up and costumed as the Thing. The idea was to show the creature as it shrinks from the towering Amess to the average sized Mangenes to the diminuitive Curtis and finally to a shapeless rabble. Several attempts, however, proved unsatisfactory.

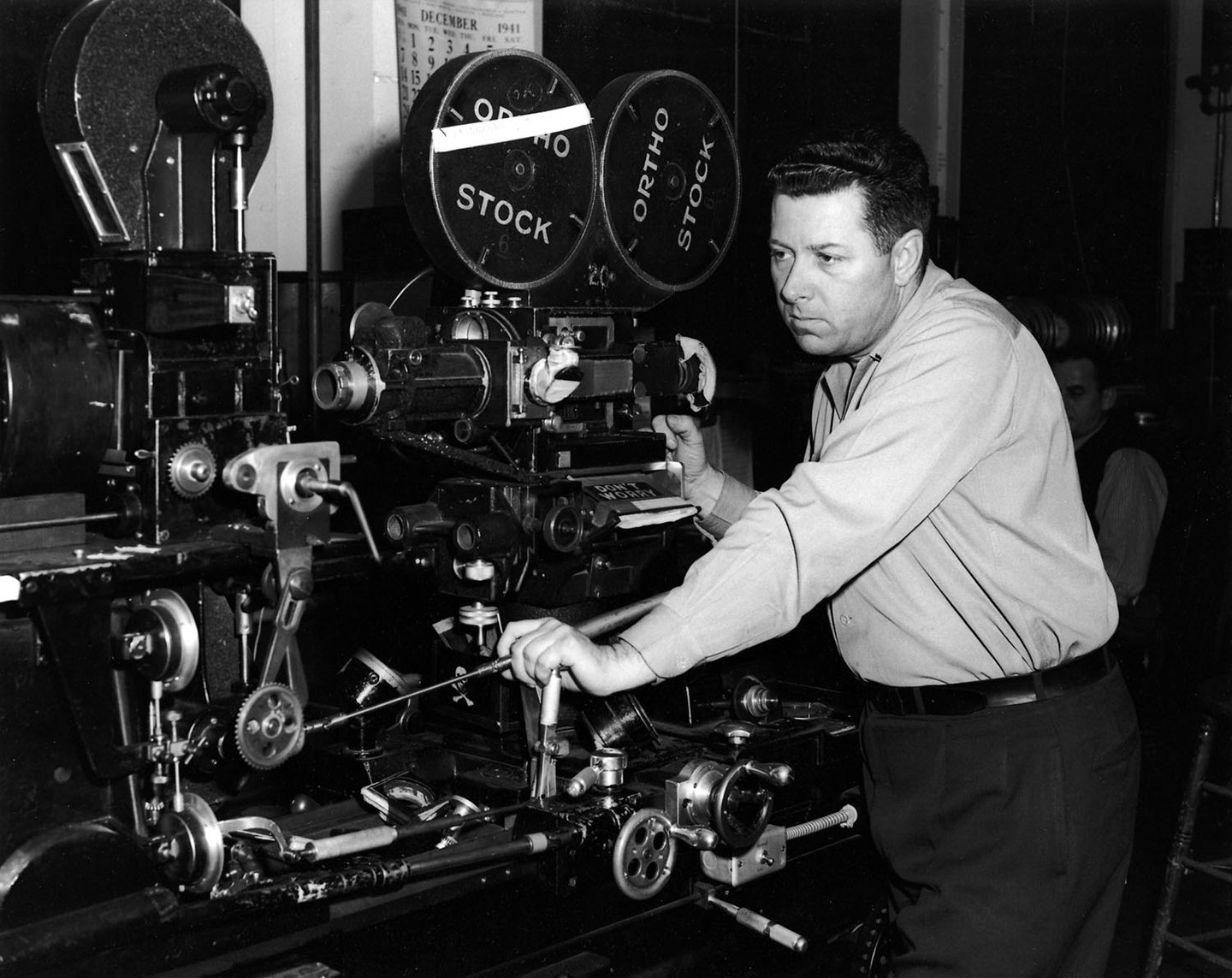

At last, Linwood Dunn, ASC — head of the RKO camera effects department — was sent for. Using his optical printer, Dunn blended and smoothed the separate shots together with a series of elaborately controlled dissolves. Working on a Moviola, he laid a piece of film, which had been developed to a medium gray tone, over the scene. He scribed markings resembling lightning in the emulsion of the gray film, animating the bolts frame by frame to strike the head and hands of the creature. He then made a high-contrast dupe of the gray film and brought it up to a solid black.

The scribe marks initially betrayed their origins, being unnaturally hard and flecked with bits of emulsion. When Dunn printed the lightning bolts over the scene, he corrected these problems by putting them slightly out of focus and printing through a piece of organdy gauze to disperse the light and give the edges a glowing effect.

When complete with lighting, smoke, and a soundtrack that has to be heard to be believed, the scene convincingly depicts the giant alien being cooked away by 1.6 million volts of electricity.

Principal photography was wrapped March 3, 1951. In postproduction, Dunn added clouds to the bleak skies of the Montana footage. The final certified cost was $1,257,237 — one of the more expensive pictures of the time despite the "no-name" casting.

Film editor Roland Gross told us he was forced to drop a number of scenes because of a decision, following an early preview screening, to keep the Thing indistinct. These cuts included closeups of the Thing as well as group shots in which Arness appeared with other players. In one cut sequence, the Thing kills two scientists and a sled dog and injures Eduard Franz in the greenhouse. As it stands, the scene is described by the surviving scientist while the investigators react to the off-camera corpses and find the body of the dog stuffed in a cabinet.

Another excised scene showed the Thing hurling a guard into the base's oil pipeline, plugging up the system. In the final cut, it is assumed that the Thing has sabotaged the base's heating system deliberately.

Dimitri Tiomkin's score underlines the eerie atmosphere of much of the picture with strings and the wailing of four womens' voices. The effect resembles that of the theremin (an instrument that produces varying electronic tones), which was introduced in Miklos Rozsa's music for Spellbound (1946) and was subsequently used by Rozsa and other composers to impart an eerie effect into the sound tracks of numerous psychological thrillers and science-fiction movies.

The score is appropriately jaunty for the scenes of cheerful camaraderie that open the picture, and punctuates the action sequences with the same sort of brash rambunctiousness Tiomkin employed for the fights and shootouts of Duel in the Sun (1946) and Hawks' Red River (1948). The romantic scenes are backed by several good pop tunes. The destruction of the Thing is particularly well handled: a strong buildup to the moment when the bolts of electricity are unleashed, followed by a gradual "crumbling away" of the orchestra as the alien expires.

The film’s full title was intended to be, simply, The Thing. But as the release date neared, a novelty song of the same title was introduced by Phil Harris and became immensely popular. Fearing that the public would relate the picture to the song, the studio had the words, "From Another World" added to the main title. The advertising campaign was revamped and a message was sent out to the theaters: "The Thing of the photoplay has no relation whatever to the subject of a current popular novelty song."

There is only one difference in the film as seen in the theaters in 1951 and the re-release prints, TV prints and tape recordings shown today, but it is a major one. The original release print order emphasized that the scenes showing the Thing should be "printed down" (darkened) so the character could never be seen clearly. Audiences were given only a hazy impression of the creature's appearance. They saw him indistinctly when he was frozen in a block of ice, almost got a good look at him in a brief instant when he crashed through a door, got a few tantalizing glimpses in the scenes in which he was wrapped in flames and in the moment when the electrical bolts strike him at the climax. No stills of the Thing itself were released. He remained a mysterious, enigmatic presence who, in the best show-biz tradition, left the audience feeling "a little hungry."

When the reissue copies were made, these instructions were completely ignored (purposely or not) and Jim Arness is easily recognizable in almost every appearance. Also, several of the suppressed stills of Arness in makeup have surfaced in recent years, most of them candid shots devoid of intended lighting effects. In its way, the picture is effective in its present incarnation: audience curiosity is satisfied, but at the sacrifice of the extra measure of suspense that the imagination can supply when menace is suggested rather than clearly seen. The creators of the picture knew what they wanted.

Echoes of Universal's 1931 Frankenstein resonate, not only in the monster's appearance but in the staging of a few scenes, such as the one in which he unexpectedly smashes through a door which the players manage to close again. The general approach, however, is antithetical from that of the old Universal school of horror film. Here the focus is not upon the monster, which typically is both hero and villain, but upon those being menaced. With few exceptions, the "leading man" of old was a rather dull fellow (what casting offices called "a juvenile lead") and the traditional leading lady is a not-too-bright pawn who looks good in a peignoir when being carried away.

Hawks, obviously, would have none of this. In his only venture into the genre he utilizes the same he-man and smart woman approach he brought to his marvelous Westerns, war stories, gangster dramas, romantic comedies, mysteries and newspaper yams. The emphasis is upon characters who are brave, strong and resourceful. The women are as courageous and efficient as the men. The dialogue is realistic and often humorous, even in the romantic moments. The monster is a menace to be dealt with as one would deal with a band of marauding renegades, neither more or less. It is a pleasant change, and it works. Nevertheless, The Thing definitely is a horror picture, one of the handful that really hands the customer a good, healthy scare.

At the time The Thing was released, many were disappointed that a less human-like creature was not devised and that the original story was not followed more closely. For some, this opinion remains unchanged. With the innumerable unsuccessful "blobs," rubber suits and mechanical monsters that appeared during the years that followed, this writer soon became convinced that Hawks and company were right in their every decision.

This opinion was fortified by a look at director John Carpenter's 1982 remake — photographed by Dean Cundey, ASC — which did all the things we wanted the original version to do, and did them well. It hewed close to the Campbell story and it was in excellent color. Not one of the gory moments was left out or played offscreen, and it featured an ever-changing and petrifyingly horrifying monster via some of the finest special effects ever accomplished. Yet, scary and technically admirable though it was, it failed to capture the human qualities that made audiences of 40 years ago worry seriously about whether or not the actors would be gobbled up by the Thing.

In 2001, The Thing from Another World was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry.

In 2011, a prequel to Carpenter’s film — also entitled The Thing — was released, while a new feature based on the original “Who Goes There?” story was announced in 2020.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.