Ticket to Ride: Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC

The veteran cinematographer recalls his adventures as a still photographer.

Stephen Goldblatt was a young, ambitious still photographer in Swinging London when he scored the gig of a lifetime: hanging out with the Beatles to shoot images that would help promote their latest recording, the soon-to-be-legendary White Album (aka The Beatles). It was 1968, well before he became a renowned ASC cinematographer.

Part of the assignment involved driving around town with the Fab Four, looking for promising spots to grab some snaps. Goldblatt recalls, “It was very casual, and there was no security with us. We were just doing it ad hoc, stopping the car and hopping out whenever we saw an opportunity.

“At one point, we spotted this house with a nice garden, and the Beatles hopped over the fence to pose in the garden. The owner was in his front room at the time, reading the paper after lunch on a Sunday afternoon. He looked up, and suddenly he noticed the Beatles, at the height of their fame, standing in his garden! Can you imagine?”

Goldblatt shakes his head, chuckling at the memory during a Zoom session with AC. The events that led to this plum opportunity recall an old maxim often attributed to the Roman philosopher Seneca: “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” Goldblatt remembers the circumstances well. “Jeremy Banks became my agent as soon as I left art/photography school,” he says. “I started out at the Guildford School of Photography, but I left after two years because I was offered a job with a magazine where Jeremy was the picture editor. That magazine folded, and then I became a picture editor on Fleet Street, at the ripe age of 21. By then, Jeremy had joined the Beatles’ company, Apple Corps, and established a studio on Pimlico Road, in a space that used to belong to Anthony Armstrong Jones, who had recently married Princess Margaret. I was shooting there with one or two other photographers while also going to film school at the Royal College of Art; behind the fixer trays in the darkroom, I found a few sweetly discreet portraits of the princess.

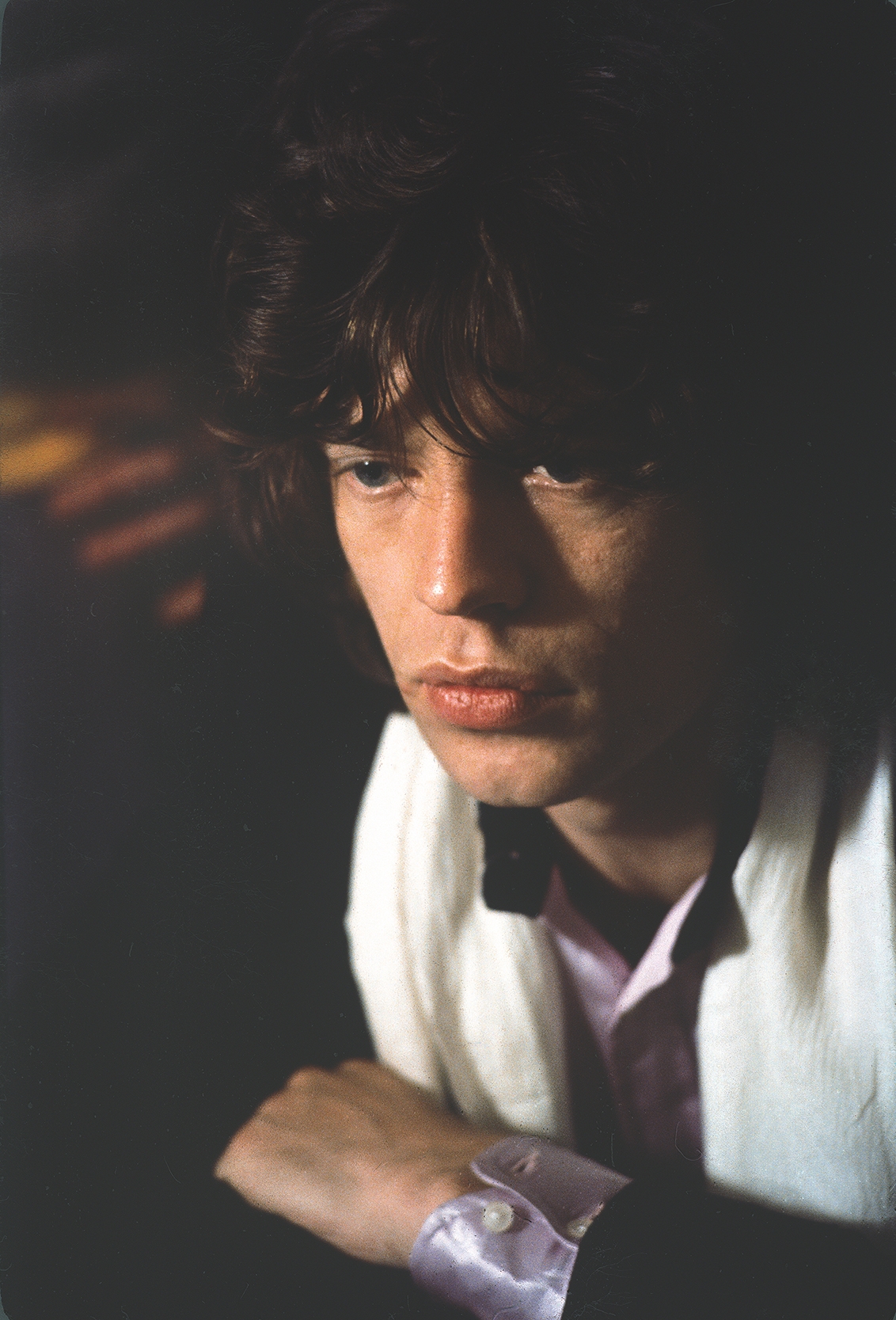

“The Beatles had the White Album ready, and they needed new pictures to promote it,” he continues. “They wanted two photographers — one was the very famous Don McCullin. He was a war photographer who wasn’t really suited for that gig, but such a great guy. The other was me — ‘the least-known photographer in London,’ as Jeremy said. But by then, Jeremy knew I could get the shots, because I’d already done maybe 20 assignments. So Jeremy knew I wasn’t just a student, and he pushed for me to get the Beatles gig.

“Don turned up with two assistants, but I was by myself,” Goldblatt adds. “That proved to be an advantage, though. In perhaps the most well-known photo I got with the four of them together, they’re all looking at Don — but it’s much better that they’re not looking my way! I had the best seat in the house. I’ve still got a big print of that particular photo right over my desk at home.”

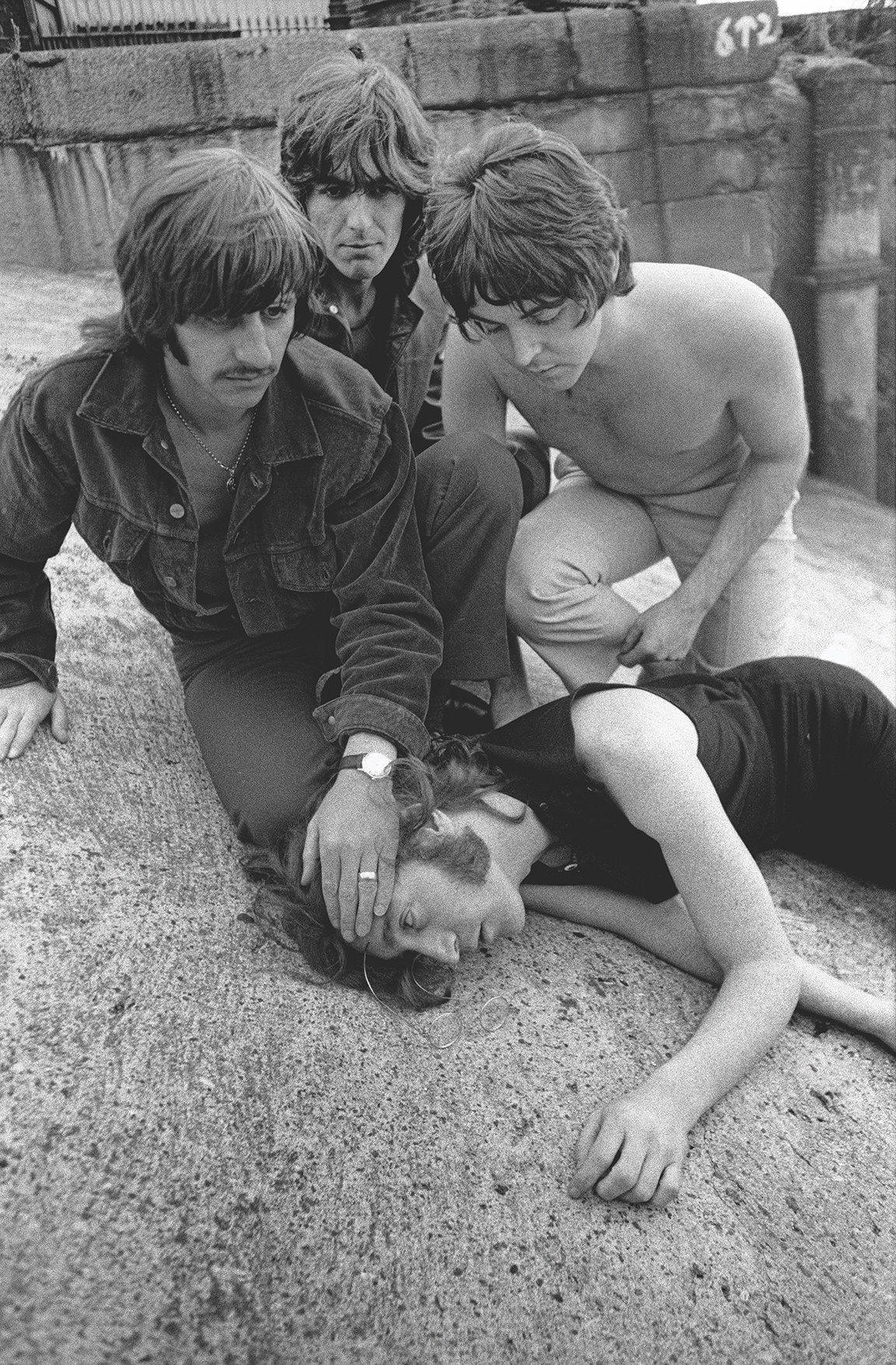

Goldblatt’s work with the Beatles yielded other memorable stills, including an unsettling shot of Paul, George and Ringo crouching around a prone John Lennon lying on the ground — an image that would attain an aura of supernatural prescience after Mark David Chapman gunned down Lennon in 1980 (photo shown at left). “The Beatles were just fooling around, joking and laughing, but for one second they got serious. Later, of course, when John was murdered, the photo became an eerie echo of the tragedy. I heard the news while I was shooting a commercial at the Coconut Grove in Miami, Florida; I was riding in a car with the director, on our way to a location, and the news came over the radio. I didn’t even think of trying to exploit the photo, though; I was just upset that John was dead.”

Goldblatt was destined for a life behind the camera. Born in South Africa in 1945, he recalls being around 5 years old and watching his father load an 8mm camera. The family moved to the U.K. when he was 7, and the precocious child pursued his future career with vigor. “I started taking pictures when I was 11. Of course, my parents wanted me to be a doctor, like my father, or a lawyer, like their friends. Everyone was going to Cambridge and Oxford if they were smart, or really lucky. But I wasn’t interested in that path at all, so I didn’t study. I had an overriding interest in photography.”

He eventually enrolled at the Guildford School of Photography. “My parents despaired that I was going to go to this art school. My mother’s idea of a photographer was the guy who took passport photos in the local shopping arcade. But I went to Guildford, and I think I spent three months trying to light two eggs, making compositions in 4x5 — which was good training, I suppose.”

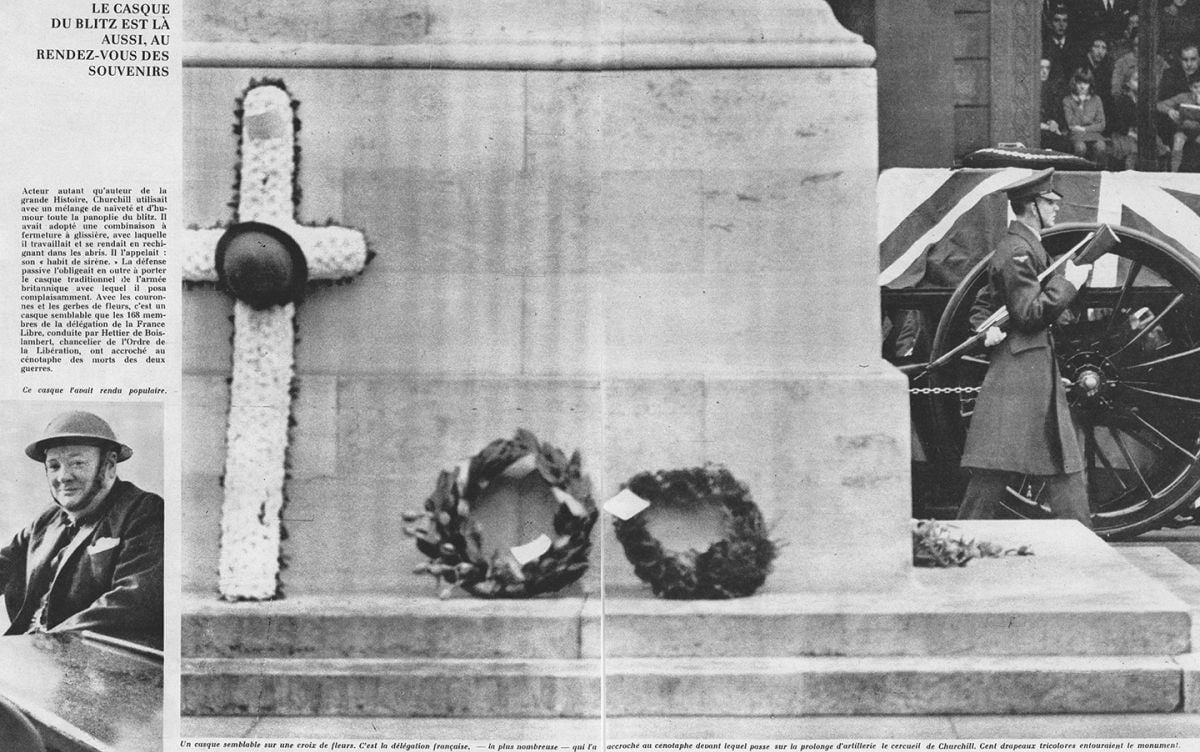

When World War II British Prime Minister Winston Churchill died, opportunity knocked. “At the time, there was a big rivalry between Life magazine and Paris Match,” he says. “Paris Match had the advantage of geographic proximity — they could get their material to Paris in an hour. But Life had money, and they flew staff in on their Boeing 707 airliner, which had color and black-and-white developers, picture editors, everything. On their transatlantic flight back to the States, they could lay out the magazine with the edition on Churchill’s funeral.

“Paris Match only had about six photographers, and they needed something like 46, so they engaged our entire photography school as stringers, just to see what would happen. The photograph I had in my head was to show the war memorial Cenotaph in Whitehall — there was a space next to that, and then Downing Street, where all British Prime Ministers live. So I had a frame in mind with the Cenotaph on the left, the Duke of Wellington’s gun carriage carrying Churchill’s body, and Downing Street on the right. I went to Whitehall with a 28mm lens, and I stayed rooted to the spot until six in the morning. I didn’t move, I didn’t pee, I didn’t eat, even though there was nobody there but me — it was just deserted. Finally, at sunrise, I saw the police sweeping the street for security purposes, and I was sure they were going to kick me off my carefully chosen spot. But then I saw 30 Frenchmen in berets laying lilies on the Cenotaph for the funeral; the lilies represented the people of France and the Resistance. And as they walked toward me I said in my schoolboy French, ‘I’m working for Paris Match, and these flics are going to kick me off the street.’ They said, ‘Come with us.’ They let me stand there with them, and I wound up getting three pages in Paris Match.”

Goldblatt soon found work as a summer intern at a magazine called London Life, which was published by the Sunday Times. There, he met his future agent, Banks, and began compiling a portfolio. The editor at the time was Ian Howard, a tabloid-minded veteran of Fleet Street with an intimidating presence. “He was a 300-pound Scotsman and he had me scared to death,” Goldblatt says. “Eventually I told him I had to go back to school, and he said, ‘Are you crazy?’ I felt I had to finish, so I did go back to Guildford, but then I decided Ian was right — I already had the Paris Match spread under my belt, plus the three months I’d already done at London Life, and he hired me back to join his staff.”

The job led to many adventures, including one daring gambit that paid off when Goldblatt scored exclusive photos of England’s national football team after their famous victory in the 1966 World Cup. “That was a real coup for me,” he says. “I’d been dispatched to the Royal Garden Hotel in Kensington by Ian, who told me to try to get into the team’s party.” Before the festivities got started, Goldblatt did finagle his way into the hotel, where he landed in a reception line for Prime Minister Harold Wilson. “As I got close to Wilson, I was sure the game would soon be up,” he says, chuckling at the memory of his youthful chutzpah. “But before I could be presented to the prime minister, I followed a waiter into the party through the kitchen, just as I’d seen in the movies. I was the only photographer in the world who got in!”

Goldblatt is living testament to the benefits of such intrepid initiative, even if it did mean flouting protocols from time to time, or telling a fib. On the White Album shoot, for example, “George Harrison kept giving me the side-eye,” Goldblatt says. “I was supposed to be a complete unknown who hadn’t photographed them before, but I actually had already done a shoot with them — I’d been among the 50 photographers at the press conference for Sgt. Pepper! Eventually, George approached me and asked, somewhat suspiciously, ‘Haven’t I seen you before?’ Naturally, I lied: ‘Oh no, sir, I don’t think so.’ Fortunately, he just let it go.” Or, perhaps, just let it be.

His memories of working on Fleet Street reflect Goldblatt’s work ethic and tolerance of long grinds. “Ian Howard would call me at five in the morning, which was usually when he was going to bed, and tell me what he wanted that day. I was sometimes covering three or four parties a night, five or six nights a week. I slept during the day. But I didn’t mind, because this was London during the ’60s, and Twiggy was there! I didn’t care if I was supposed to be at a party or not, or if I got kicked out, but more often than not I got to stay, because I looked the part — I wore a nice, dark jacket, with nice pants. The stereotypical Fleet Street photographer of that era was a sleazy-looking guy in an old raincoat and a hat, smoking a cigarette with a Rolleiflex around his neck.

“Those guys always used a flash, but I never did — it was a big mistake. In parties with rich or famous people, shooting without a flash was more discreet — if you weren’t aiming a big flash in their faces, they liked having their picture taken. I had a Nikon 35mm camera with a Nikon 35mm lens and Tri-X film; I might carry a second camera with a 75mm lens on it. Zoom lenses weren’t popular then, because they were very expensive, and they weren’t very good. I developed my own film, and I had a notebook to take down all the names — the Marchioness of this, the Duke of that. I’d leave the party at 11 at night and go back to Fleet Street, where there was a darkroom, and I’d develop my rolls of film. It was all contact printing.”

Goldblatt says he had a “fire in his belly” to shoot that helped him endure the grueling hours. “Some friends of mine I’d hired from photography school only lasted a week, because the work was just too hard for them.” His ingenuity and cunning in pursuit of the shot also set him apart: “That’s the secret, in the end — you’re not given access, you’ve got to get it.”

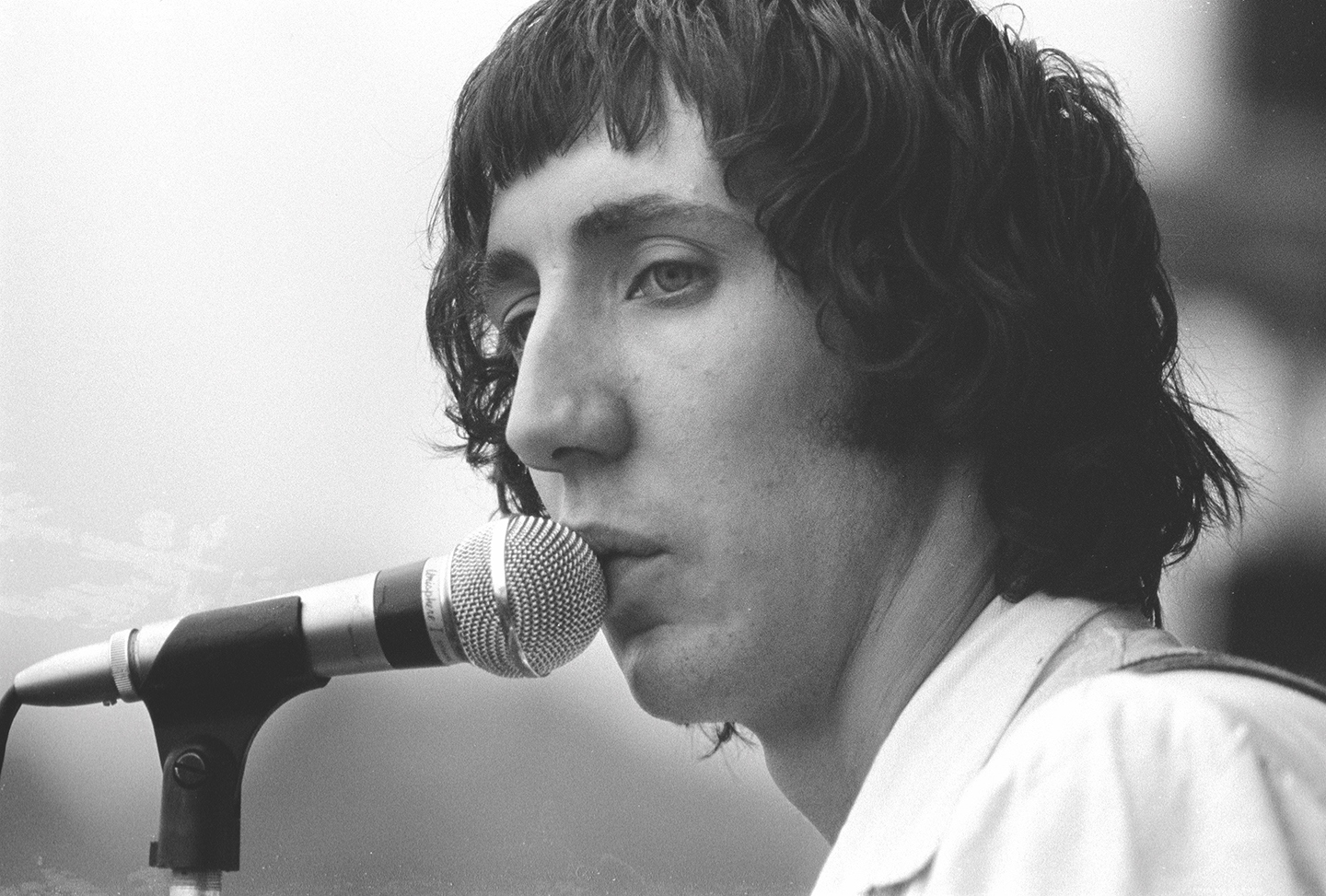

In 1969, he was hired to shoot the Isle of Wight Festival, a massive rock concert featuring some of the biggest musicians of the era. He’d already done the Beatles shoot, and the event was being organized by three brothers — one of whom had been a classmate of Goldblatt’s at the Royal College of Art. “I had exclusive access to shoot onstage, but to keep things exclusive, I planted three big Alsatian dogs under the stage so no other photographers could creep through,” he says. “The dogs actually caught [famed photographer] Richard Avedon’s son! He gave me his camera, and I opened it up and ripped the film out. He was lucky he didn’t get eaten!”

Goldblatt’s access led him to capture a thrilling shot from behind the Who’s Pete Townshend as the rock icon jumped in the air while holding his guitar aloft in front of the show’s massive audience. “There were so many people at that show that security simply couldn’t stop them,” he recalls. “They came right over the fences. At a certain point, to save lives and prevent a riot, the organizers just let everyone in and made it a free concert. The atmosphere was great. If you look closely at the Townshend photo, you can see a line of photographers along the front of the stage, but they were getting nothing special — the best perspective was the position I had on the stage.”

His still-photography work set Goldblatt on the path to his future career when he started doing special shoots on movie sets twice a week. “The British film crews were very disciplined,” he says. “Most of them were ex-Army, with 40-year-old operators who had fought in World War II when they were 18. The assistant director might be a former tank commander — when one of those guys yelled ‘Quiet!’ it was dead quiet. The films themselves often looked terrible — they used the old-fashioned 5K-2K-1K setups on top of each set wall, and they’d just turn more of those on as needed. There were some wonderful cinematographers, though, and what I enjoyed was the camaraderie of being on a film set. I could have made a career as a still photographer, but I found it pretty lonely. Plus you were always fighting and competing to get one up on the other guys, and I never enjoyed that part of it.”

After he moved on to pursue his career in cinematography, Goldblatt always kept still cameras handy, using them to capture artful and intriguing behind-the-scenes photos on the projects he shot, or lighthearted and revealing moments with some of the iconic actors and filmmakers he’s worked with. “The photos I take on scouts or on sets are good references for everyone, and they help promote communication,” he says. “On Angels in America, I was very concerned about lighting and color continuity, so I was taking reference shots with a little Canon point-and-shoot camera the production had bought for me. I was astonished at the colors it produced. Some of the reference photos I took of Al Pacino and Meryl Streep ended up on the front page of The New York Times Magazine. The resolution wasn’t great, but the color was good. I didn’t embrace the shift from digital to film immediately, but I could see that digital was really coming along. While I was still on that show, I also bought Nikon’s first digital camera.

“The camera I use a lot now is the Leica M10-P, usually with a 25-year-old 35mm Leitz Summilux or a 50mm Summilux,” he says, estimating that he has more than 60,000 negatives stashed in his archive. “I also like the Canon EOS-1D X, because it’s indestructible, and the new Canon EOS R5, which is mirrorless.”

Goldblatt still favors a more organic approach to stills work. “If an image has some truth to it, and it hasn’t been manipulated to death, I think the viewer feels that,” he says.

Pondering the arc of his career behind cameras for both stills and movies, Goldblatt notes, “I don’t know why I’m a stills photographer; it just came naturally for me. Film lighting was a tough thing to learn. My stills portfolio got me a special place at the Royal College of Art, which is where my film studies began in earnest. That’s also where I met Tony Scott, who was a classmate of mine. I was the only student in my year — or any other year — who wanted to be a cinematographer; everyone else in the class wanted to direct. So I shot many of their films — and f----d them all up! But that’s the best way to learn.”

In 2023, Goldblatt was presented with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award.