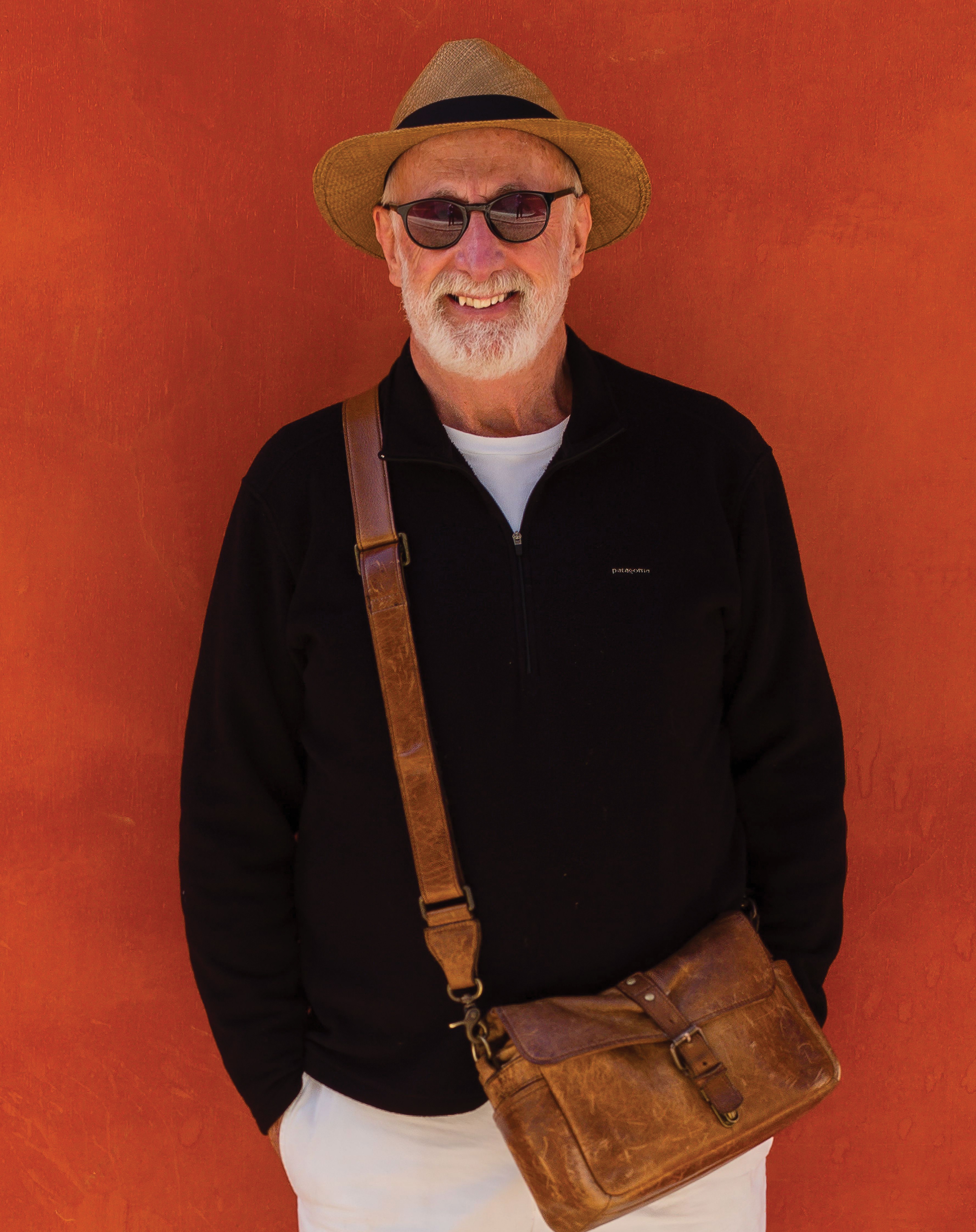

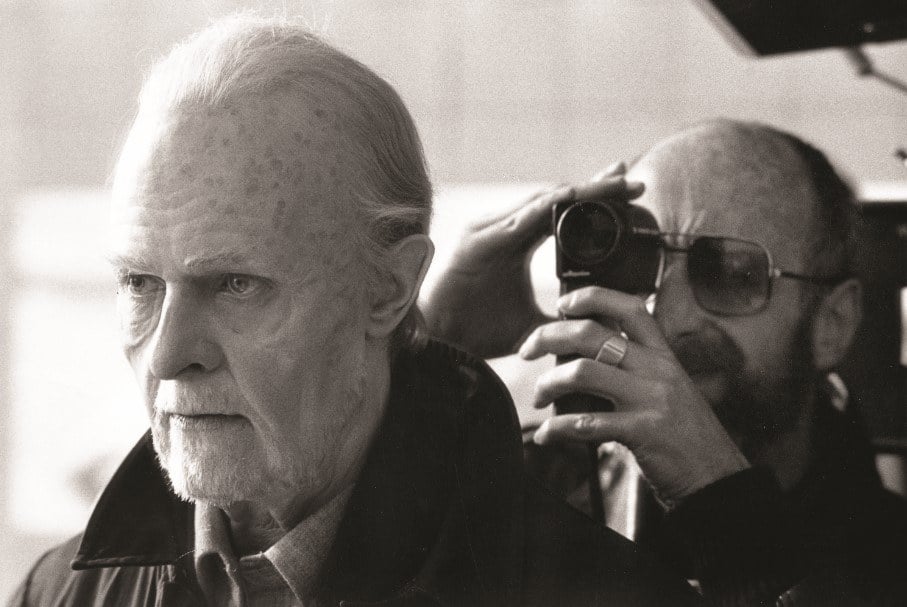

Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC: An Eye for Imagery

The cinematographer’s exceptional professional journey began as a young man’s gamble.

ASC Lifetime Achievement honoree Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC has actually enjoyed two illustrious careers: one as a still photographer in London during the swinging ’60s (see AC June 2021), and the other as the cinematographer on an impressive array of acclaimed features, box-office behemoths and noteworthy television productions — including The Hunger, Lethal Weapon (AC April ’87), The Cotton Club, The Prince of Tides (AC May ’92), The Pelican Brief (AC Jan. ’94), Batman Forever (AC July ’95), Angels in America (AC Nov. ’03) and The Help (AC Sept. ’11).

Goldblatt was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and emigrated to London at age 7 when his anti-apartheid parents began falling under dangerous government scrutiny. As a child, he did not care for his new home country, the schools, the sports or the teachers, and recalls that he was “held in equal disregard.”

Exciting Discoveries

Life turned around completely when Goldblatt enrolled at the Guildford School of Art “without my parents’ enthusiastic consent,” he says. “They didn’t know what art school could mean or what it did mean for me.” Finally, he was engaged in something he could be passionate about and studying with others who shared his interests. “I remember working with what was called a Gandolfi view camera. It took 4-by-5 film, and I spent months shooting eggs against a white backdrop strictly to study composition.”

An unexpected turn of events quickly launched his career: Winston Churchill died, and his funeral procession promised to be a spectacle for the ages. Paris Match mined the Guildford student body, tapping “every student with a camera” to document the event from as many vantage points as possible. Goldblatt stood with his Pentax — “the cheapest mirror camera you could buy” — at a spot in Whitehall, waiting from midnight until late the next morning for the cortege. He captured many unique moments and came away with some impressive photographs. “I got three pages in Paris Match, which was fabulous!”

With his work splashed across the pages of an internationally respected magazine, he decided he was ready to move on with his career. “I was foolish enough to think I didn’t need to go to school anymore,” he says. Goldblatt landed an agent and an internship with the popular magazine London Life, and he was off and running as a professional photographer. He nightly attended fashion and high-society parties, sneaking candids of celebs including Twiggy, Marianne Faithfull, James Taylor and even a young Helen Mirren. “London was very open at the time,” he notes.

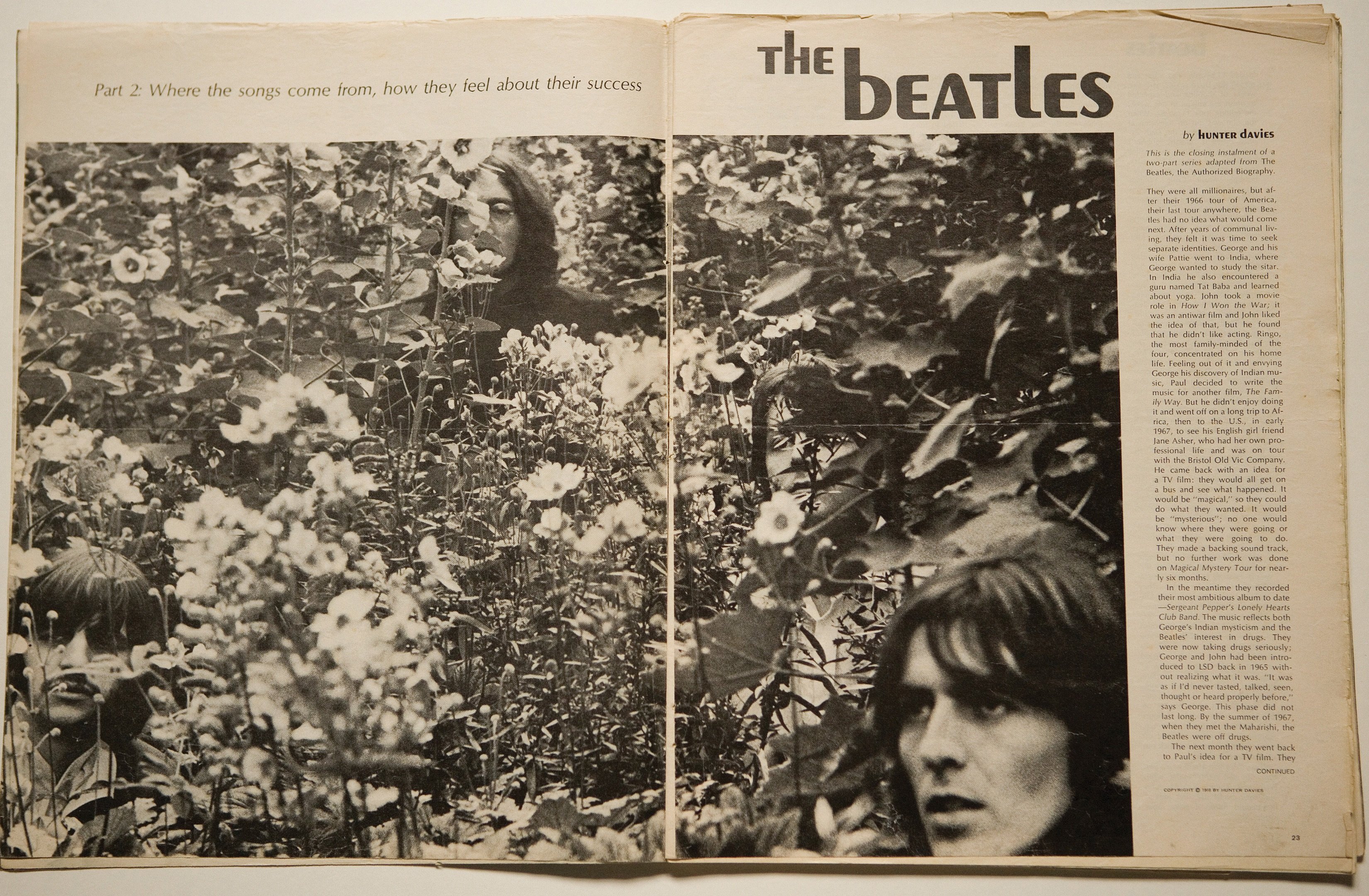

A lucky break enabled Goldblatt to serve as a backup photographer on the Beatles’ photo sessions for what became known as “The White Album.” He managed to grab shots of the Fab Four from angles where they seemed less aware of the camera. “I was a fly on the wall,” he says. Many of these images made their way into album art, books and posters and became iconic.

Film 101

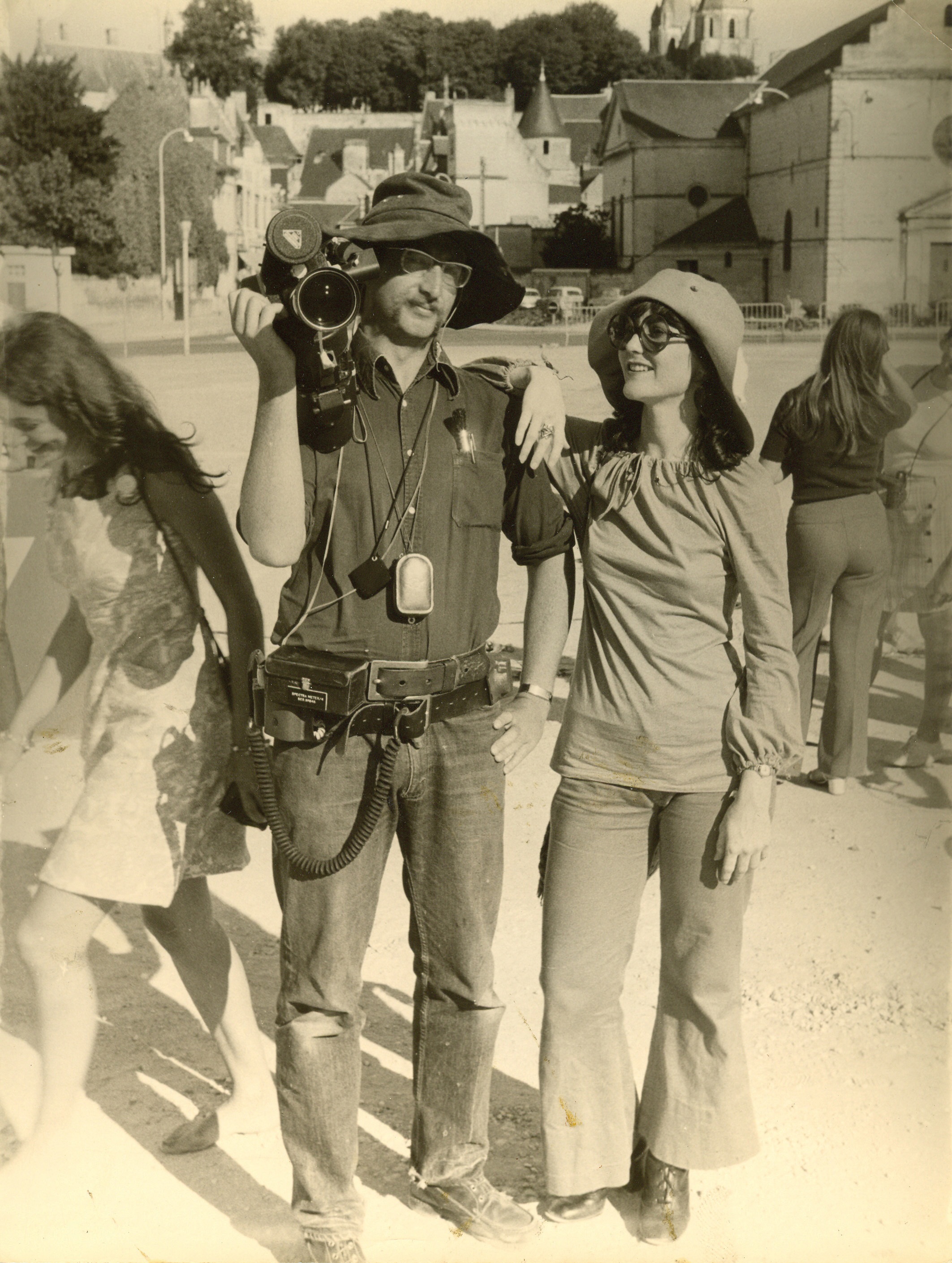

It was a part-time gig as “special photographer” for British Lion Films that awakened Goldblatt to the possibility that cinematography might be a stronger passion for him than still photography. “I was already feeling the loneliness of the long-distance photographer,” he quips. “You go off to spend a summer in Africa — you go to the airport by yourself, [travel] by yourself, and at the end of the day, you go back to your hotel.” By contrast, his British Lion assignments involved “a group that appeared to be a very happy one, from the top all the way down. It seemed like what they were doing was fun. Yet I’ve never been at such a disciplined workplace — the ADs were former tank-regiment commanders! You could hear a pin drop on set.”

While the collaborative aspect of filmmaking inspired him, the camera department he observed did not. “I saw how they lit and thought, ‘Why, that looks ugly!’ They used such an old-fashioned lighting system, with hard light and light everywhere. Shadows had to be banished. There was nothing artistic about it. And I wondered what it would be like if I could shoot movies.”

He applied to the Royal College of Art to study motion pictures. His application was accepted, and he enjoyed working with classmates that included Tony Scott, with whom he would collaborate in the future. In a sea of directing hopefuls, Goldblatt shot a lot of student films, learning more about the craft each time.

After receiving his degree, he sold his collection of stills cameras to force himself to hold out for cinematography jobs, which were much scarcer. “I was determined to be a cinematographer, and I had to make good — I didn’t have any other financial resources.”

Imagining From Experience

Goldblatt attributes his ability to previsualize how a scene would look on film to his still-photography background, and he still believes this skill is essential to a cinematographer’s success. He also made a close study of the era’s 35mm Eastman Kodak cinema emulsions. “I think engraved on my heart is ‘5254, 5247, 5293 …,’” he declares. “I learned, from working, what I could and couldn’t do with those film stocks. There was a serious level of anxiety at first because you couldn’t see what the image actually looked like until dailies; you had to constantly imagine what everything would look like. Eventually, after you’ve done enough work, you know what you’re imagining is what it’s going to look like.”

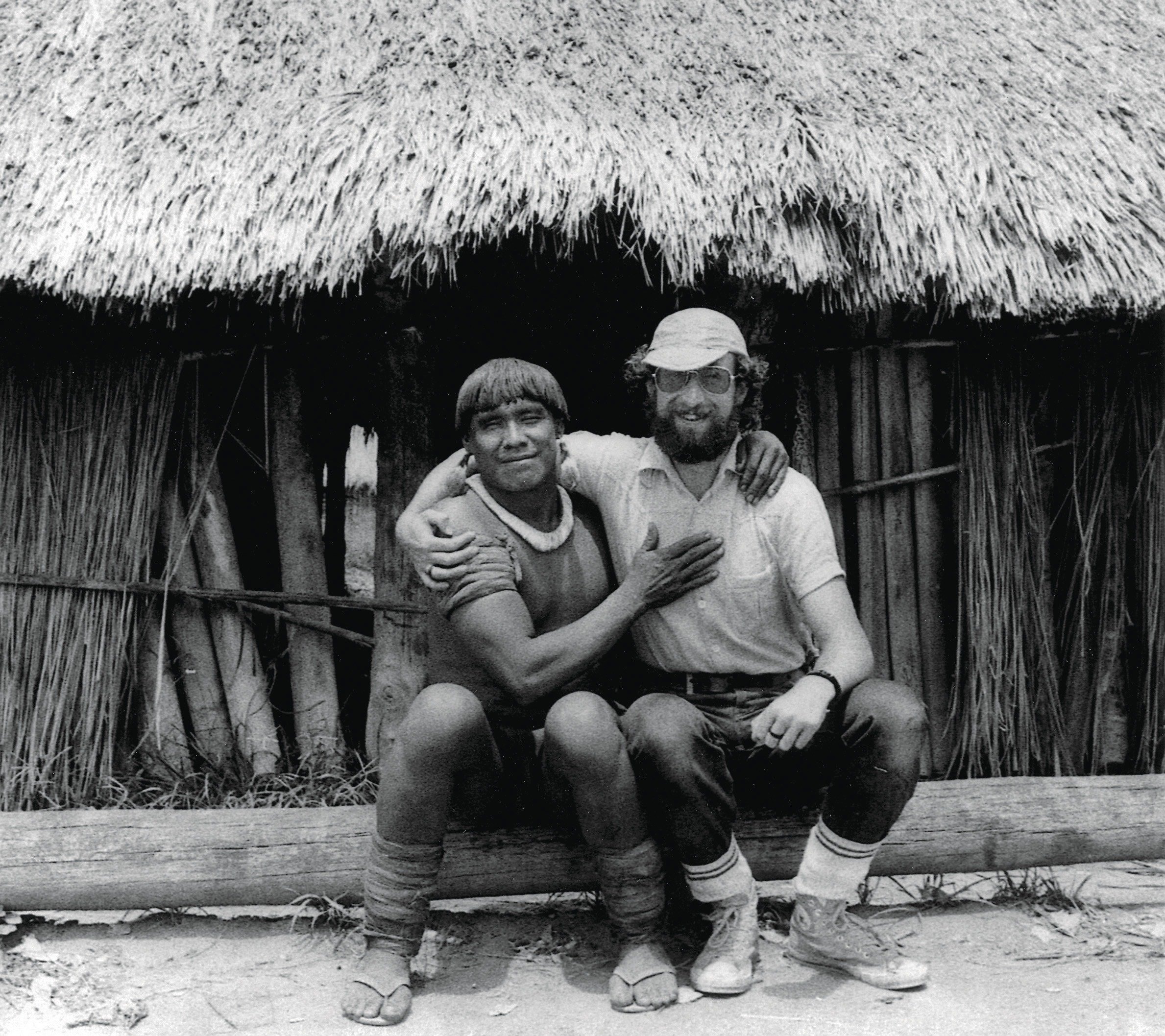

An early opportunity to shoot motion pictures arose in the documentary arena. Goldblatt shot two ethnographic documentaries for Granada Television, which took him, a director and small crews to the Amazon and to the Andes Mountains to film for many months at a time. He remains proud of the work he did in trying conditions, but, after witnessing many criminal acts, watching a director almost die — and, on one job, lapsing into a coma himself — he decided to change course.

He returned to London and began shooting commercials. “I didn’t know it,” he says, “but that was a calling card to feature films.” He started working for Tony Scott and Brian Gibson, who were making names for themselves in the commercial world.

The Big Screen

When Gibson was offered his first feature, the anarchic 1980 punk-rock film Breaking Glass, he took Goldblatt along. “I was flying by the seat of my pants,” the cinematographer recalls, adding that this actually proved to be an advantage. “I didn’t know how to even ask for a conventional lighting setup. I would light through windows, expose wide open with candlelight — all these things that became very much in vogue within a few years. But I did it because I didn’t know how to do the other stuff.”

Goldblatt’s next project was the sci-fi thriller Outland, starring Sean Connery and directed by Peter Hyams, who typically shoots his own features. “Peter hired me to fire me,” says Goldblatt. Realizing Hyams intended to photograph the film himself, Goldblatt decided to make the most of it.

Numerous in-camera effects were to be shot with a new front-projection system, IntroVision, that used glass plates. “I realized if I didn’t learn about front projection, rear projection, semi-silver mirrors and all that stuff, I would be fired,” Goldblatt says. He credits visual-effects supervisor William Mesa with bringing him up to speed. “Through the goodness of his Buddhist-inspired heart, Bill put me through a three-week intensive course on how to do all the tricks. The most important thing I learned was that you couldn’t measure the light on the effects elements. You could take an incident-light reading of an actor’s face or body, but then you’d have to balance it all up by eye.” It was a skill Goldblatt soon mastered.

Tony Scott’s The Hunger, a 1983 vampire thriller starring David Bowie and Catherine Deneuve, gave Goldblatt a golden opportunity to show what he could bring to a very stylized story. He and Scott got on quite well, but the director, who shared a fondness for shadows, frequently second-guessed Goldblatt’s work. “Tony was in the habit of saying, right before we started shooting, ‘Switch something off.’ So, I began to put up extra lights — unbeknownst to him — so I could switch two or three of them off and he would be happy.”

On the production, Goldblatt experimented with several lighting techniques he previously hadn’t had the budget to attempt. He sometimes lit with Brute Arcs positioned far away and tried various effects he’d thought about but never used, such as placing the key light — directed through a large diffusion frame — on a dolly that pushed in toward an actress moving closer as the lens dollied into her close-up. “This technique increases the softness of the light, wrapping more,” he explains. “In a wide shot, you can’t get the diffusion as close as you might want to really shape the face. Generally, you change the setup for a close-up and bring the diffusion closer to have softer light. If the shot is dollying in toward the talent, then you don’t have the chance to ‘clean up’ the closeup in a separate setup. So, pushing in the diffusion actively achieves this and keeps it out of the shot.”

Today, he credits Scott with the film’s beautiful aesthetic and chief electrician Martin Evans with creating ingenious solutions to difficult problems, including “hanging an arc light, pointing down at about 45 degrees, from an oversized trapeze swing.”

Blockbuster Breakthroughs

Without question, Lethal Weapon was a leap into the mainstream. “It wasn’t a huge budget — around $20 million,” Goldblatt notes. “But it made so much money!”

Written by Shane Black, the script opens with a young woman’s suicide, and Goldblatt brought an iconic 1947 photo by Robert C. Wiles to his interview with director Richard Donner. The image shows a young woman who’s just committed suicide by jumping off the Empire State Building and landing on a parked car, which appears to be cradling her lifeless body in its dented roof. “I thought it was such a haunting image, so I brought it with me, and Donner offered me the movie on the spot,” Goldblatt says. In fact, the director had the opening scene rewritten to reference the image specifically.

Goldblatt and Donner got on well, and the collaboration continued on Lethal Weapon 2, another action-heavy production that allowed the cinematographer to apply his in-camera-effects experience to a major car chase involving Mel Gibson and Danny Glover speeding through the streets of Los Angeles. The filmmakers initially attempted to shoot the scene on location, but Donner became frustrated by the video assist — he couldn’t see his actors — and quickly shut the shoot down to figure out a better way.

The solution involved using rear projection on a soundstage at Warner Bros., and Goldblatt supervised the shooting of the necessary plates. He also requested special processing of the material to be projected, increasing the silver content in the positive to increase the contrast.

The resulting images looked excessively contrasty to the naked eye, but solved a problem Goldblatt had noticed with this type of work. He explains, “Once these images were projected, the light spill would desaturate them and reduce the contrast in the plates — so they read as having normal contrast in the final version. I don’t think that had ever been done before. Donner was able to direct the actors, and we were able to make the scene look very real.”

He credits camera operator Ray De La Motte with helping to sell the illusion. “We wouldn’t rehearse, and I encouraged the dolly grip to move the camera as if we were filming from an independent car,” he recalls. “Ray really gave a sense of movement to the shots, as if we were in a car chase.”

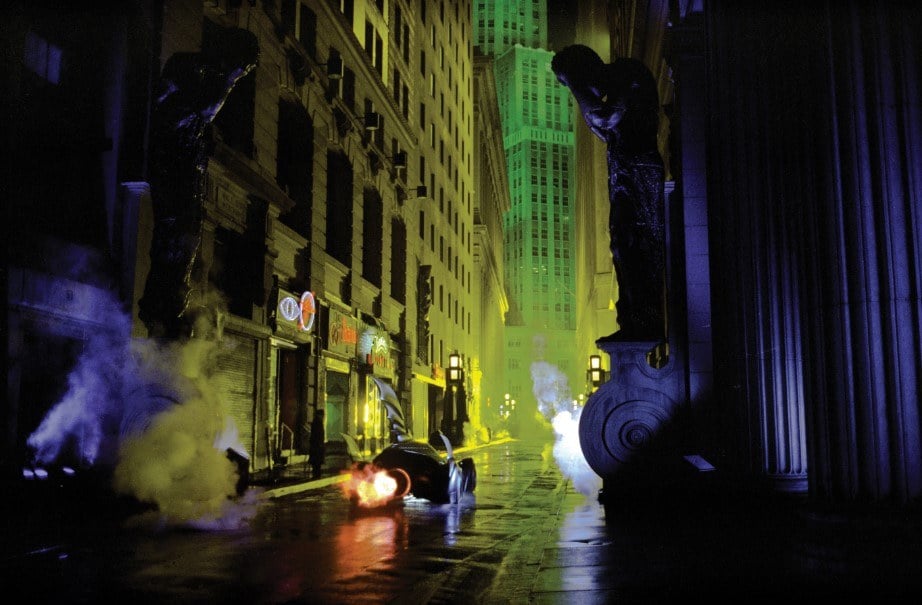

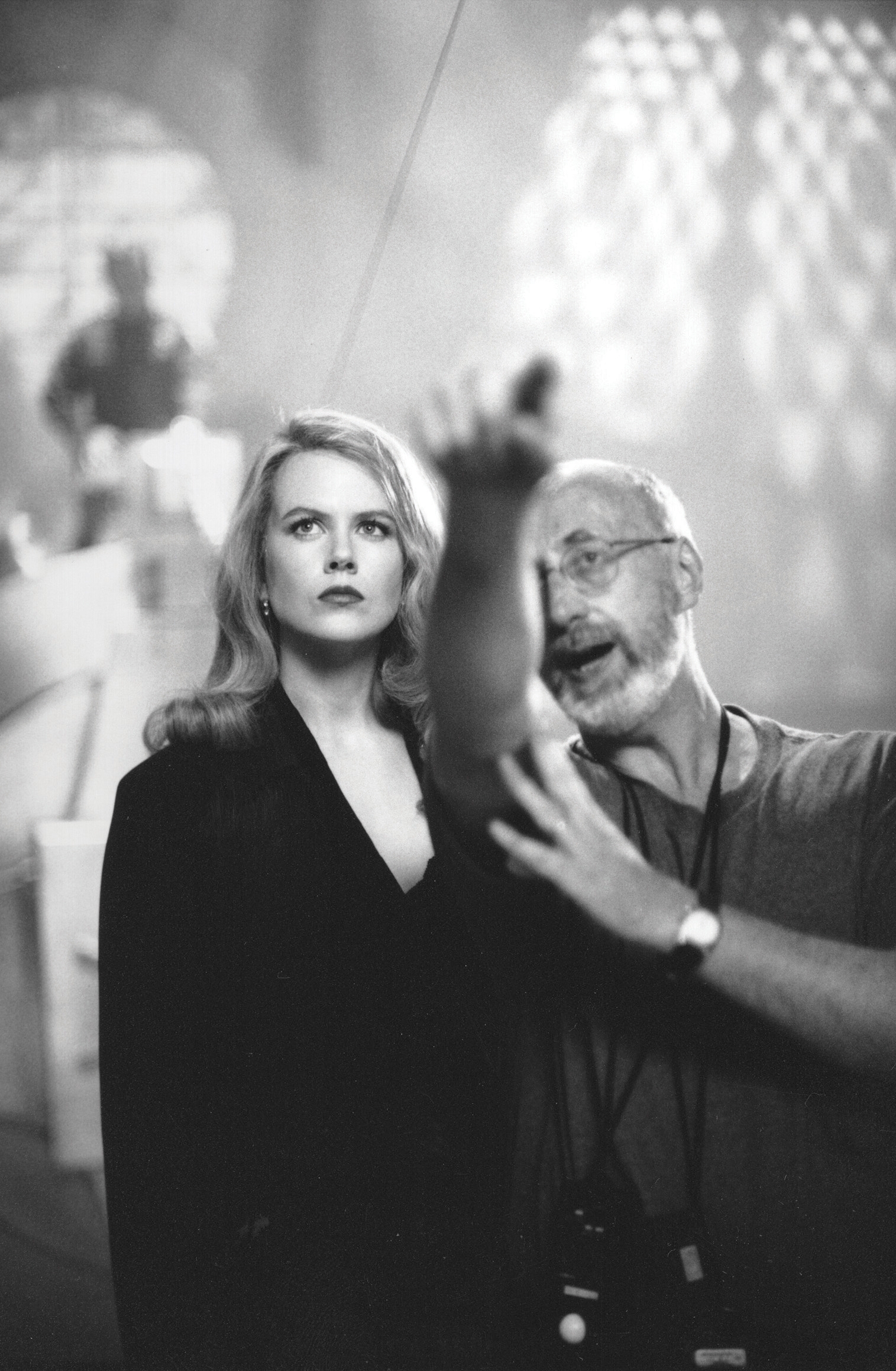

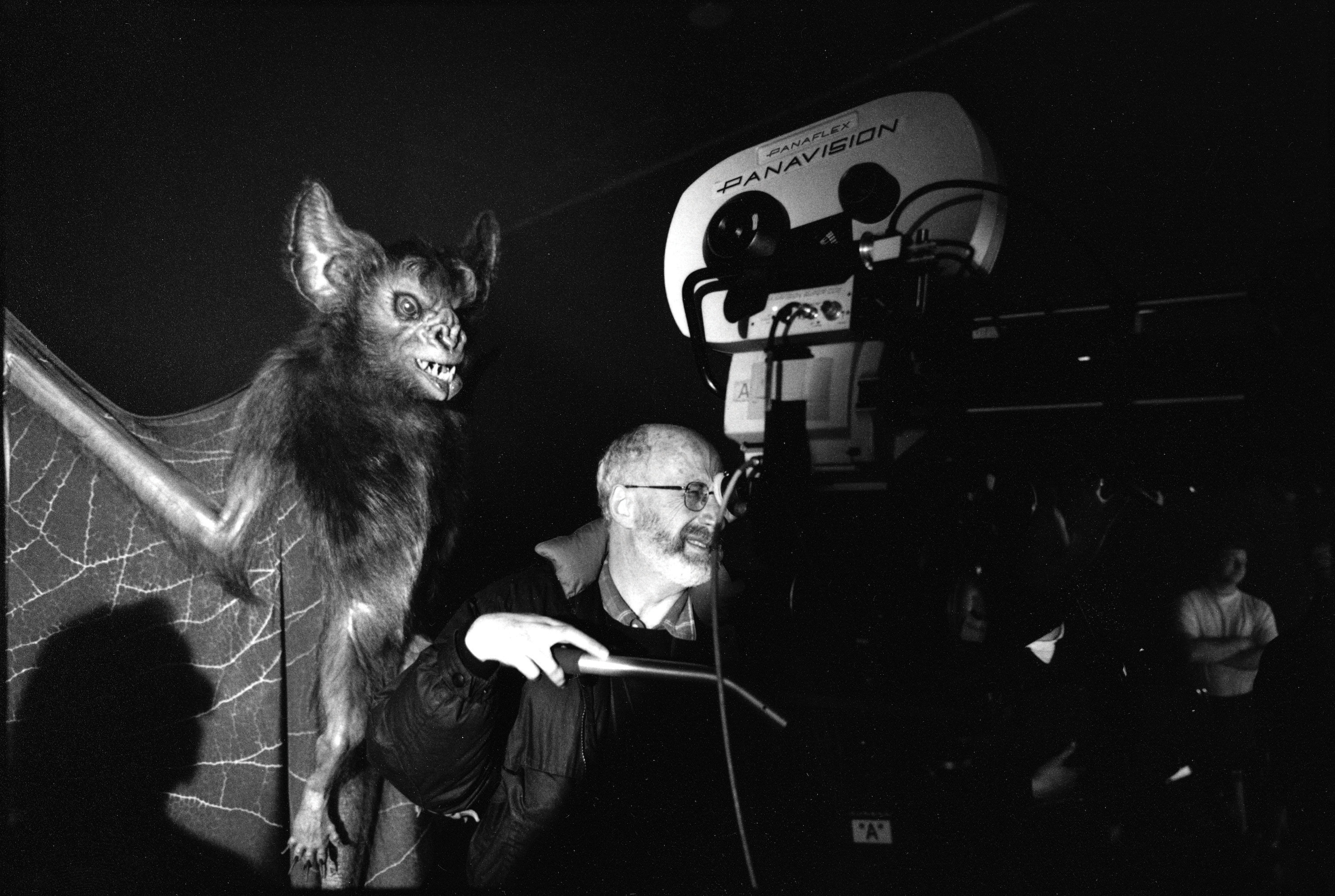

Goldblatt worked with director Joel Schumacher on the Warner Bros. features Batman Forever and Batman & Robin (AC July ’97). In many ways, he says, these films were among the last of an era. “They actually built sets the size they appear to be onscreen; there was virtually no greenscreen or bluescreen. When the Batmobile had to screech through the streets of New York, we lit up Wall Street, and we lit up to 40 stories high from the ground! It was the biggest setup I ever had to do and ever will do — because today, most of that would be done with visual effects. We had the wonderful [visual-effects supervisor] John Dykstra [ASC] take our work over and then increase it, as it were, but the technology compared to what we have now was primitive.”

On the A-List

Goldblatt also distinguished himself in the early days of HBO’s “prestige productions,” starting with the 2001 World War II drama Conspiracy, which depicted the infamous Wannsee Conference. Goldblatt convinced director Frank Pierson to shoot handheld “with the great operator Trevor Coop using Super 16mm cameras,” which allowed the filmmakers to complete 10 script pages per day and achieve a documentary-style immediacy. The success of this project led to another HBO production, Path to War (AC May ’02), directed by John Frankenheimer.

It was on Goldblatt’s next outing for HBO that he forged what he considers to be his most rewarding collaboration with a director — even though they got off to a somewhat rocky start. The project was Mike Nichols’ miniseries adaptation of Angels in America, based on Tony Kushner’s acclaimed play.

“I went to meet Mike at the Hotel Bel-Air,” Goldblatt recalls. “We had a wonderful meeting. He didn’t talk about the work, but then, he never did; he’d always talk about experiences in his life, which I realized were actually illuminating the inner life of the story.”

When prep commenced, however, Goldblatt found Nichols to be so insufferable that he gave executive producer Cary Brokaw two days’ notice to find a new cinematographer — in the third week of principal photography. Goldblatt recalls, “I was getting into the cab that would take me home. I was very upset, and Mike’s assistant grabbed my arm, pulled me out of the taxi and said, ‘Mike must see you!’ I went and saw him, and he looked at me and said, ‘I can’t help myself.’ Until he fully trusted someone, he could be very difficult, and he knew it. But he told me that he did trust me and asked me to stay on.

“Skip many months ahead, and I wanted to share an idea for how I thought a very big, elaborate moment could be shot, and Mike stopped me and said, ‘I don’t want to hear; I don’t want to see the rehearsal; I don’t want to know anything about it. I want you to surprise me.’ Then on the day, after the first good take, he embraced me and kissed both my cheeks.” The resulting sequence shows an angel (played by Emma Thompson) appearing in spectacular fashion.

Goldblatt went on to shoot Nichols’ last two features — the searing drama Closer (AC Dec. ’04) and the political comedy Charlie Wilson’s War (AC Jan. ’08) — and many more striking films.

Throughout his career, Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC has made time to mentor younger filmmakers through the Sundance Institute and other organizations. Actress Octavia Spencer noted, in presenting Goldblatt with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award March 5, that he had also educated her during filming of Tate Taylor’s period drama The Help. Notably, she recalled how he kindly explained to her “in great detail” why it was important for her to hit her mark in a particular scene — a professional courtesy she not only learned from, but never forgot.

Goldblatt has been honored with two Academy Award nominations (for The Prince of Tides and Batman Forever), three Primetime Emmy nominations (Conspiracy, Path to War and Angels in America), three ASC Award nominations (The Prince of Tides, Batman Forever and Angels in America) and the Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award.

In his remarks at this year’s ASC Awards ceremony, he expressed gratitude to those who have helped him over the course of his career, among them Nichols, Donner and Taylor; camera operators De La Motte, Will Arnot and Henry Tirl; and gaffers Evans, Colin Campbell, Steve Mathis and Jim Plannette.

“However,” he noted, “beyond all colleagues and collaborators, my wife Deborah’s strength, insight, courage, patience and love have meant everything to me.”