Walking Dead and Loving It (Part I of II)

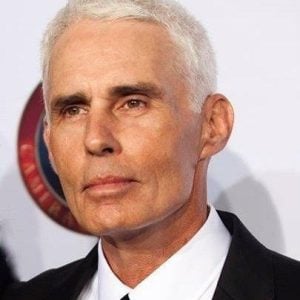

Cinematographer Stephen Campbell details his visual approach to the apocalyptic horror drama The Walking Dead.

Director of photography Stephen Campbell — alternating episodes with Michael E. Satrazemis — is currently helping to shape the nightmare world of The Walking Dead, one of the most-watched scripted TV series on television, which boasts legions of fans worldwide.

After graduating from Rollins College, Campbell began his career in Orlando, Florida, working at a camera rental house before gaining experience as a documentary cameraman. He then worked his way up as a camera assistant and operator on such films and TV series as Superboy, Passenger 57, Vanishing Son, SeaQuest 2032, The Cape, Rosewood, From the Earth to the Moon, The Waterboy, Mortal Combat: Conquest, Monster, The Punisher, The Sopranos, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, Zombieland, Last Man Standing and Endless Love. More recently, he’s been splitting time between shooting The Walking Dead and another AMC series, Halt and Catch Fire.

In 2015, Campbell earned an Operator of the Year Award nomination from the Society of Operating Cameraman for his work on The Walking Dead.

Recent Walking Dead episodes that were shot by Campbell include “Go Getters,” “Swear” and the mid-season finale “Hearts Still Beating.”

The following is the first half of a lengthy discussion with Campbell that took place before a live audience during the 8th annual Downtown Film Festival in Los Angeles.

American Cinematographer: We have the great honor today — for cinematography fans and Walking Dead fans — of talking with Stephen Campbell, who literally flew in today from the set in Atlanta where he's shooting a new episode for the seventh season.

Stephen Campbell: It’s gonna be a good one.

This will be a spoiler-free discussion today, but tell us a little bit about what you have been doing for the last 24 hours on set. You're working with director… ?

[Executive producer] Greg Nicotero, who has now directed more episodes of the show than anyone else. He's also responsible for all the special makeup effects. Greg comes from the George Romero camp way back and worked on Day of the Dead [1985]. His career has been very lengthy and very involved. He’s collaborated with all the directors on our show and got his touches all over, in part because all the zombies and prosthetics are supplied by KNB Effects, his company here in Los Angeles. Greg's a genius. Every episode, he brings new zombie designs to the set and we're just amazed. I've been on the show for four years now, and, when I first got there, I couldn't believe we were actually shooting this stuff, in part because they just keep topping themselves. They keep coming up with new concepts for either a kill or a zombie who's been torn up or caught or trapped or underwater or stuck in sand or mud. It's never-ending, so there's been a lot of creativity there that's just amazing to watch.

It was just a coincidence that the original Walking Dead comic was set around the Atlanta, Georgia, area and it ended up shooting there as well, right?

Yeah. The timing was great because when the show started — this is the seventh season —the incentives in Georgia were just being established. So [the Walking Dead producers] came in early on on the program and took full advantage of it. And that has created a lot of work for crews there.

Let's go back a bit and talk a little bit more about your documentary background. I think some people would be surprised by the number of top cinematographers who started in documentaries. Roger Deakins, who you mentioned before, did. Dean Semler [ASC, ACS], who shot The Road Warrior and Maleficent, as well. Can you tell us a little bit about how that background informs how you still work today?

In our industry and the position I'm in as a cinematographer — or even operators, or most of the other people on the set — you're constantly running into situations where you have to be able to react quickly to the unexpected. Shooting documentaries, you don't really know what you're getting into. You can't block it out and say to the subjects, “You stand there, you stand there.” It just happens. And before it does, you have to decide: Where am I going to put the camera? What would be the best angle to tell the story? So you're making those constant decisions and anticipating where the action might go — and where your cuts will be — as you're shooting.

Documentary work forces you to pre-think what you're shooting so you can almost edit it while you’re going along, in the sense that you need certain pieces to tell the story. Even on the set [of a scripted project], you're constantly having to change and shift and problem-solve. We come into the day with a shot list, and we know where the sun is going be, and we think we’re in complete control, but we're really never in control. Maybe because sometimes it rains, or the location didn't work out for one reason or another. On this show, we've had situations where they've flooded. But that documentary background makes you able to react to a situation and say, "That's not working; let’s do this instead."

Shooting features and television is all about time management. It's an art, but it's still a business that’s all about time and money. And they only give you a certain amount of time to do the work you're given in a day. When I get to set in the morning, they'll hand me sides — a condensed version of the script pages we're shooting for that day — that include a production timeline. And they say, "You have two hours to do this scene and get all this coverage." And then the next scene is a certain amount of time, and so on. And once you start to shoot those scenes, they’re very conscious of the time.

Film work is really not very glamorous. It's actually kinda brutal. And this has been a brutal season so far. We're working 14- and 15-hour days most every day. So it’s fun and it's exciting, but it's also tiring. Fortunately, I still enjoy it. I enjoy the moments.

For instance, this week we were able to shoot most of the big scenes backlit. We were able to actually choreograph the day that we could shoot with the sun. For me, that's the best way to do it. Most of the ADs — the assistant directors — don't care about the sun. They just care about making their schedule. But they don't realize that if you can keep your subjects backlit, everything is so much easier to shoot because you don't have to bring all this equipment in to control the light. You'll always have great light whenever you do it. And this week it just happened to fall that we started the day backlit and ended the day backlit. And these are some pretty big scenes with lots of bodies and lots of zombies. And, to me, it just makes it look so much better.

Tell us a little bit about the photographic approach to The Walking Dead. Even now in the seventh season, photographically, the show has maintained a fairly consistent look. In some ways, it's a visually conservative show and doesn't get into a lot of razzle-dazzle. Instead, it's quite grounded.

Yes. One of the things that drives the show is the fact that we shoot on 16mm film. And my relationship with the show actually goes back to before I actually worked on it, because I saw the pilot [“Days Gone Bye,” in 2010], which Frank Darabont directed [and was photographed by David Tattersall, BSC]. To me, that's still the best episode that’s been done on the series. I mean, he had the best combination of psychological terror without showing too many zombies, in just the way that he shot it.

But they started the show shooting film, and although they did test digital formats during the second season, they decided, "That's not the show." Because the show, being on 16mm, has additional grain in it. It has motion blur, if only because it's still going through a gate. That adds a bit of a classic horror vibe to the show. And I think they'll maintain shooting with film as we go on with the show.

Interestingly, this past week, for the episode I'm shooting with Greg Nicotero, we did a greenscreen driving sequence that we ended up shooting digitally. Now, producers are always rejecting the idea of using process trailers — which are these trailers that you can put the car on and you can move through the environment down the road. But you can also mount dollies or jibs on it so you can move the camera and the coverage isn’t so rigid. 'Cause, a lotta times you'll see traveling footage where the cameras are locked off and nothing's moving; everything's happening in a locked frame because the cameras are locked on the vehicle.

Before we get into specific questions about The Walking Dead, I'd like to discuss your career and the steps you took to become a director of photography. This is a job where preparation meets opportunity. And, for you, it was almost 20 years of preparation before you met this kind of opportunity.

Yeah, it has been a while. I started working right out of college. I went to school in Florida at Rollins College. After I got graduated, I worked at a rental house for six months. There, I got experience with all the equipment — 35mm, 16mm and grip stuff. I also kept meeting this local producer and shooter who came in all the time to rent equipment. And he asked me if I wanted to come out with him on the road as a PA/assistant to help shoot Michael Jackson’s last tour with his brothers [in 1984]. On that six-month tour, I got a crash course in every film camera that was working, from Panavision to Arriflex to NPRs to Aatons. We put our hands on very camera that was available. Then I came back to Florida, where I freelanced for a few years. We then went back on the road again with Michael in 1987 and ’88 and worked with him for 15 months. We were his documentary crew and traveled all over the world shooting on 35mm. Before the tour, I had the great experience of coming out to L.A. and prepping all our gear. We went to Arriflex and bought a brand-new Arri BL and a complete lens package and magazines and told them, “Just send the bill to Michael.” I used that camera for 15 months on the road and it sort of became my personal BL.

I then went back to Florida and the industry [in Orlando] was taking off because the Hollywood studios had just opened production facilities there. This is back in 1988, and Universal and Disney both had studios that were working. They were calling it “Hollywood South.” We had a very formal, great industry for probably 10 years. We worked all the time. It was like working in a mini L.A. in the sense that you had choices. Nothing to the extent of the volume of work being done here, but for a small market that had only seven or eight people doing each job, everybody was able to work all the time on different things, including features and episodic TV. We were always working on something.

Over time, I transitioned from assisting to operating to shooting. Each show you’d work on, you’d gain more experience: “Hey, go shoot that.” “Okay, good. I'll shoot that.” And then, eventually, you got to the point of, “We'll let him shoot all the second unit stuff,” or, “We'll let him shoot.” Then I got my card in the union as a cinematographer. Since then, I've been working in that realm and also operating when I can, because I still enjoy that craft. To me, operating is the best job on the set. Roger Deakins [ASC, BSC] still operates all of his shows with everybody that he works with. He's the operator and he makes all the choices.

But, for me, when you're doing multi-camera coverage like we do on The Walking Dead, it's much more difficult to operate and shoot because you've got to oversee all those cameras. Just yesterday we had four cameras working at once.

So my career has been a series of working at home and then having to work out of town because that’s where the work is. And production incentives drive this industry now, whereas it used to be that L.A. was where you shoot unless you had to go a particular place because of your location needs. But now, producers require incentives attached to most every project they shoot.

Because that's the least expensive way to do it.

Exactly. So, for this one, Greg wanted to be able to pan and tilt to follow the action. He wanted to tilt down and see what the characters are doing, connect them and then move the camera. So we mentioned that we’d need a process trailer and the producers said, "No, way too expensive." So the visual effects supervisor, Victor Scalise, said, "Well, maybe we could do it on greenscreen but shoot outside.” Okay, that’s great. We've done it before. We just make the light move to make it feel like the car’s moving. We also took all the windows out of the car to make things easier and Victor will later add the windows back and put reflection effects on 'em. It all works pretty well and looks good. Well then they realized that they have to rent the digital cameras to do this. So it actually cost more money to shoot digital than it would've cost to just get the process trailer.

So the show is still film-driven. We shoot at least three cameras every day, but for the last three days, we've had four cameras because we have a lot of zombies and effects going on. And I think it'll continue in that way. We also shoot with prime lenses instead of zooms because of the glass. We've always felt that primes have a better, more solid feel to them. It's much cleaner. You can also shoot into the sun easier without the light spraying all over the place. Since season four, which is the season I joined the show [as an operator, in 2013], we've been shooting all primes. And it just continues to add a cinematic quality to the show.

We shoot in 1.78:1, which most HD shows are shot on. But we then squeeze to 1.85:1, which is what a lot of the stuff that airs that you'll see on the big screen is — they add an extra squeeze to it so it crops a little bit. Those are some of the ways in which the show tries to continue in that genre of making it feel like the old zombie horror movies. And the film grain also really does a lot. When I go to telecine, the grain is flying all over the place.

Not only are you using a medium — film — that's more than 100 years old, but a camera format, Super 16, that was invented in the 1960s and video assist that's at least 20, 25 years old.

That’s right.

So you’re going old-school.

Very old-school. And we shoot with Arri 416s, which are probably at least 10 years old. And they even have an SD tap — standard definition. So when you're at the video village, the images look like something from 25 years ago, which everyone has to get used to. I shoot Halt and Catch Fire with the Alexa, and on set we’re looking at images that are crystal clear. That's exactly what you're gonna get, because the monitors are the best money can buy. All the producers and the director are looking at this really great image. On The Walking Dead, the image is pretty bad. You can't tell anything from it.

On The Walking Dead, there's still a little bit of magic in postproduction.

It's always a mystery. [The directors and producers] don't really know what it's gonna look like until they get dailies. It's not like on a set where it's in HD: "Is that what it's gonna look like? Well, can you make that a different color?" or "Can you make that darker?" There's no discussion because they're looking at a pretty ratty-looking image.

It's basically VHS quality.

It is. So that, to us, makes shooting a little easier in the sense that they don't say, "Hey, what does this look like?" There have been times that relied on faith — you'll see in one of the clips I’ve brought to screen today, from the fifth season episode “Four Walls and Roof.” It’s the scene when Rick [Andrew Lincoln] takes out the people from Terminus in the church. The director [Jeffrey F. January] wanted the scene to be really, really dark. We went really dark. So they would look at the video assist monitor and basically see nothing, but one writer-producer kept asking, "It's gonna be dark, right?" And I said, "It's gonna be really dark. Don't worry." And he kept saying, "Well, I'm concerned about that wall back there." And I said, "Well, that's the video assist camera [in the tap] and it's just opening itself up to see." In that situation, I’ll take reference stills with my Nikon DSLR and show them the ratios and what the image is going to look like. Well, that scene is really dark. I mean, you can hardly see them in there. But that's what we were going for.

If I get in any situation where I want to look at the ratios, I’ll just take a still using the same numbers that I would use to shoot the film. So it's your shutter speed, the ASA and the T-stop on the lens — you just apply that to your still camera. I used to use a Polaroid camera for this. Back when we only shot film, you would take stills and reference on the Polaroid what your exposures were. And you'd keep a book of what all the days' work was in case you had to go back and reshoot something.

Does shooting on film have something to do with the amount of makeup effects and it making them look right?

Definitely. They tested [switching to digital capture] in season two and shot both formats to see the result. And the digital formats they tested were always way too sensitive and too sharp. That's been an issue for a lot of actors out there, men and women alike. Digital just shows every blemish or other imperfection. So many shows shooting digitally use a lot of filters to smooth out the image. Otherwise, it’s just so clean and so dynamic. As a result of those tests, they decided, "The zombies look too prosthetic-y or rubbery or plastic-y." Film just takes the curse off that and smooths the edges, so to speak.

Each year, [the producers] approach the idea of going digital, but they've kind of stuck by film because that look has become kind of a character in the show.

At this point, it might actually be jarring to the audience if the show went digital.

Oh, man, it's truly jarring. I mean, the digital stuff I was telling you about… We shot that last week, and when we were at dailies and the Super 16 film was done, all of a sudden the Alexa footage comes up. Well, there on the screen are the same actors we’ve been working with for years and suddenly they look totally different. It's just so clean and crisp. It looks — it's just not the show at all. So, I think The Walking Dead will stay in the film world for a few years to come.

In the second part of this discussion, Campbell details his photographic approach to three specific scenes from his Walking Dead episodes “Spend,” “Four Walls and a Roof” and “Twice as Far.”

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.