We Are Not Alone: Contact

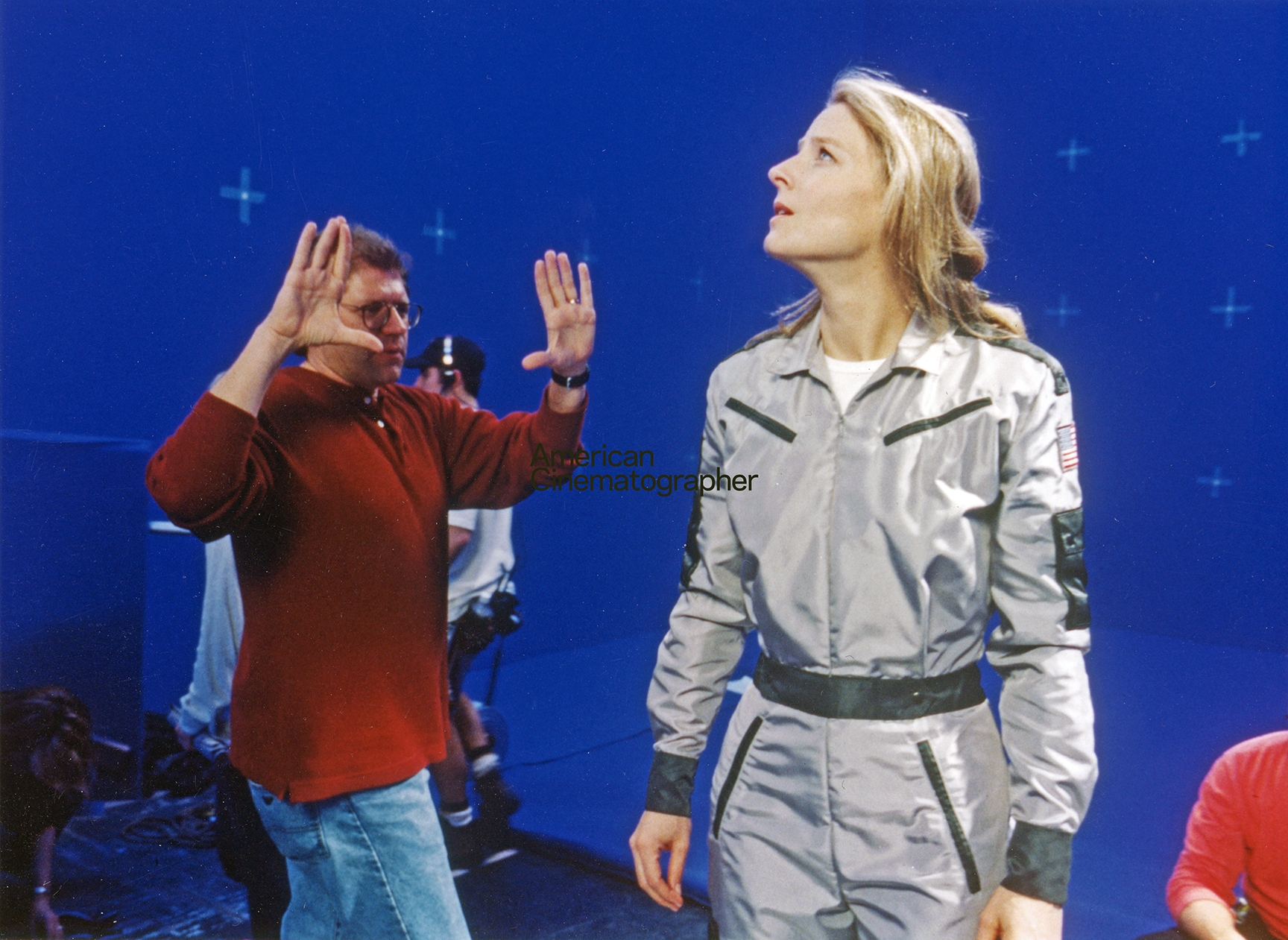

Director Robert Zemeckis and cinematographer Don Burgess, ASC propose an answer to one of humanity's most profound queries.

This article was originally published in AC July 1997. Some images are additional or alternate.

Unit photography by François Duhamel, courtesy of Warner Bros.

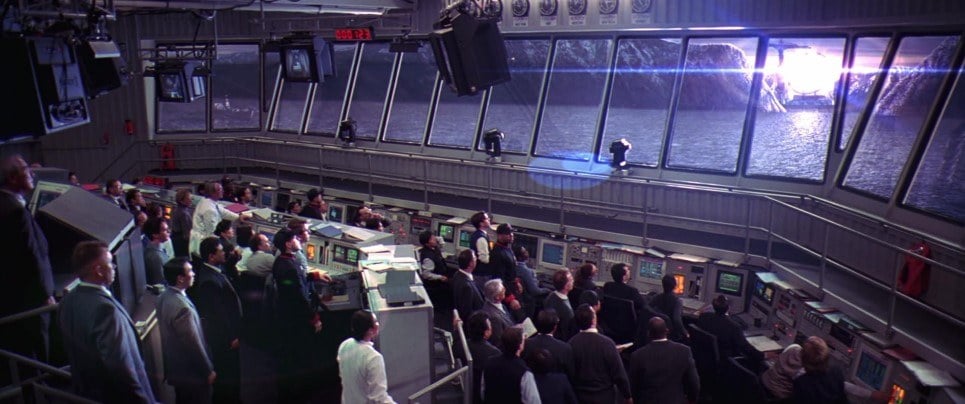

On a brisk January afternoon in West Los Angeles, an "historic moment in human history" is being realized on Stage 16 at Culver Studios. The set replicates the bridge of an aircraft carrier, where scientists, politicians and military personnel are monitoring the aquatic launch of an extraterrestrial starship. Overseeing this undertaking are a grim-faced mission commander (Tucker Smallwood), a surly National Security Advisor (James Woods), and a spiritual guru (Matthew McConaughey), who is serving as an advisor for this transcendental mission.

As a digital clock counts down the remaining two minutes to launch, all eyes focus on a number of snowy video screens displaying the craft's lone pilot — human astronomer Dr. Eleanor "Ellie" Arroway (Jodie Foster) — as she attempts to finesse the vibrating vessel. "Everything is all right. Do not abort! I can read you very faintly but I'm okay to go!" Ellie cries out from the cockpit. Hesitation fills the air. Suddenly, Ellie's sightless (and perhaps psychic) confidant, Kent Clark (William Fichtner), pipes up and offers a ray of hope, "I can barely hear her, but I think she's okay; she says she's ready to go!" The mission commander briefly contemplates this quandary before declaring, "Initiate launch sequence — on my mark!"

This command center is one of many intricate, earthbound facades fashioned for director Robert Zemeckis' screen adaptation of Contact, the best-selling novel by late astronomer/author Carl Sagan which postulates mankind's first contact with an extraterrestrial intelligence. The book's realistic yet fantastic narrative is what prompted Zemeckis to choose Contact as the follow-up project to the tremendously successful Forrest Gump (see AC Oct. '94), which broke worldwide box-office records and earned Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Direction. Gump also garnered ASC and Academy Award nominations for director of photography Don Burgess, ASC (The Evening Star, Forget Paris), who was again behind the camera on Contact.

Regarding this new picture, Zemeckis remarks, "It deals with the fantastic issue of whether there is intelligent life in the universe, but it works on many different levels. What I find compelling about the story is that it's about what would really happen here on Earth. It's more an examination of humanity than anything extraterrestrial, which I thought was really clever.

"But [in various drafts of the script], the essence of Carl Sagan's book always got clouded by the idea of aliens. It's not about big bugs, weird creatures or starships coming down here — the extraterrestrial intelligence talks to the Earth in the truly realistic language of science, and that's what makes it most credible.”

“Contact is definitely told from Ellie's point of view, so all decisions about where the camera should be were structured from where she was, what she was doing, and how she saw the situation.”

— Don Burgess, ASC

The director adds, "This is not a giant special-effects extravaganza, even though it's a giant special-effects movie. What we're using for special effects is more hardware-oriented than nature-oriented, and I like to use special effects most effectively to create realism rather than alien landscapes. Although there are some [extraterrestrial environments] in Contact, we tried to keep the film rooted in reality as much as possible."

The aircraft carrier set, and its function in the plot, is a case study of Zemeckis' aim for a realistic suspension of disbelief. Situated below the bridge are two rows of scientists and technicians poised before computer monitors alight with astral schematics, thermal charts, and statistical equations. A large bay of windows before them looks out onto the horizon. Through the artistry of digital effects, the onscreen vista will be overwhelmed by a colossal alien craft contoured to resemble the atomic symbol.

But for now, the scenery beyond these slanted panes is nothing more than a massive bluescreen. Positioned in front of the azure curtain are multiple banks of flashing Maxi-Brute nine-light fixtures (operated via computerized dimmers) which radiate sporadically upon the actors. Cinematographer Burgess notes that this interactive lighting situation simulates magnetic energy fields that encircle the vessel before its launch. He explains, "The machine is spinning to generate all of this energy, and now it's at a 100 percent [energy level] and is emitting a tremendous amount of light. It's actually way out in the ocean, but it's so bright and so powerful that all of the light is being thrown back — it's actually penetrating into the ship, and having an effect on the light in the foreground. The effect of Ellie in the pod was actually shot a month ago. But since we've got [the nine-lights] computerized on dimmers, we can match the interactive lighting of what we did then with what we're doing now."

“Although there are some [extraterrestrial environments] in Contact, we tried to keep the film rooted in reality as much as possible.”

— Robert Zemeckis

Multiple Formats, Multiple Stocks

Following in the footsteps of their work on Forrest Gump, Zemeckis and Burgess ran the gamut of shooting formats while making Contact, which will be exhibited in the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Primary production work was captured with 35mm Panavision Platinum cameras, but practicality also led to the use of the 65mm format, since its larger size negative greatly lessens any image degradation caused through effects work. Sync-sound shots were captured with Panavision's System 65, while a lightweight Beaumont VistaVision camera was employed for MOS and Steadicam work. Zemeckis offers, "We had a lot of effects shots in the movie, but because the VistaVision silent cameras are very cumbersome, we decided to go with 65mm — although we did go with VistaVision for some shots. You can't put blimped VistaVision cameras on remote heads [for shots requiring composite effects work]. We used the System 65 to try and maintain as much silence as possible. Also, if you are going to put a VistaVision camera on a remote head, you can't do a take that's longer than four minutes. So [our rationale for using System 65] was a combination of being able keep things silent and have 1,000’ loads on the camera."

Adds Burgess, "We were using a shooting style in which the camera moves quite a bit, and one shot tells the story, so we did a lot of shooting on an arm equipped with a remote head. Most of the movie was shot on the brand-new Libra 3 remote head, which you can rotate on three axis; we were able to put the VistaVision, Platinum 35mm and System 65 cameras on it. The Libra 3 is also stabilized, so you can mount it on insert cars or a Panther dolly without a lot of shake. The Libra has really responsive control wheels, so the head is very responsive to what the operator wants.

"This the first time a 65mm camera has been used on the Libra 3. Nick Philips designed some new mounts and developed new programs for the head, which also needed a brand-new computer chip, to deal with the extra weight. We had to build special brackets on the mounts themselves so that they could carry the load."

(The System 65 camera alone weighs 60 lbs.; with a loaded 1,000’ magazine and lens it comes in at 85 lbs.)

Continues Burgess, "We actually mounted the Libra head on the end of a Technocrane when we wanted to reach over the edge of the Canyon Dulce in Arizona and shoot back at Jodie Foster. When you're moving on track with an arm that long, you always have a little bit of movement to deal with, particularly when the wind is blowing. This particular head can take some of that movement out and give you a steadier image, which is tough to do if you're carrying that much weight, especially with a 65mm camera."

Besides employing the 35mm and 65mm formats, Burgess also shot Super 8 film and video footage for specific sequences. The cinematographer explains, "We shot Super 8 for a home-movie look when the young Ellie is playing with her dad or washing the car. In researching that era [the 1970s], we found that home movies were still shot in Super 8. There's footage shot of Ellie when she's a young scientist starting out a Cal Tech so we made Hi-8 video clips of her friends surprising her with a birthday cake at school. We've also got sequences that a news reporter would shoot, so we shot those in Betacam. And there are actually 35mm spherical lens images that will be used as video images. Because of all of the digital effects which have to be added to them, we preferred to start with a [high-resolution] camera negative and shoot film-for-video."

Given the immense scope of the Contact shoot, Burgess felt the need to create a reference guide in order to keep track of the details. He used Movie Magic scheduling software to log all of his information regarding each scene in the film, including filmstock, filters and special equipment. He also had numerous photo albums with still pictures from every setup as a visual reference for shooting inserts, and for recreating the look of locations while in the studio. During location scouting, the cinematographer canvassed each location with a Trimble Global Positioning System (GPS), a handheld navigational instrument which can determine the site of the sun anywhere at any time by referring to satellite and solar trajectories. Offers Burgess, "I use the Trimble to log in each location. I'll take pictures and then plot the compass headings on it. Once it's logged into the memory, I've got it for the whole show. So when I'm scouting and laying out my production schedule in May, I can figure out where the sun is going to set [at a certain locale] in, say, September."

Burgess also shot Polaroids of all of the film's major characters in their various outfits and facial makeups. In defining a cinematographic schematic for each character, Burgess took reflective readings from faces to balance variable skintones, and tried to predetermine which types of lenses might not be suitable for a particular actor's facial structure. To reflect Ellie's transition from carefree youth to confident professional, the cameraman applied additional diffusion as well as soft, frontal lighting that better accentuated Foster's features. He explains, "Her transformation in the movie is that she becomes more human. Because her mother and father die during her childhood, Ellie becomes a very isolated individual who relates to the universe better than she does to the people on her own planet. Through the course of the movie, she is better able to connect with people, and develops a romantic relationship, so I softened Ellie's look to make her more beautiful and appealing."

Despite the variety of film formats in the picture, the cameraman's use of lenses remained relatively constant. The majority of Contact was shot on a 50mm Panavision C-series lens, as web as 40 and 75mm lenses. Burgess reasons, "Wide-angle lenses are more storytelling lenses — it's a focal length that keeps the subject and the environment in focus for the most part, and it keeps your subject really connected to the environment and other actors in the scene. Contact is definitely told from Ellie's point of view, so all decisions about where the camera should be were structured from where she was, what she was doing, and how she saw the situation.

"We did go to longer lenses in a couple of instances in which Ellie doesn't connect with the people around her: the focus of the environment becomes softer, which isolates her more and accentuates that feeling. Working with wide-angle lenses is complicated, because you have a lot more information in the frame. It also forces you to tell the story from minimum focus to infinity."

Though Burgess employed several film stocks on Forrest Gump to differentiate between specific periods of American history, the assortment of emulsions utilized on Contact are supposed to illustrate Ellie's progression from childhood innocence to adult insight. As a general rule, the cinematographer used Eastman Kodak's 5293 for daytime interiors, Vision 320T 5277 for daytime interiors set at the White House, Vision 500T 5279 for nighttime exteriors, and 5248 for daytime exteriors, but some exceptions were brought about by variable weather, as web as concerns about contrast and depth of field. Burgess says, "Although most of the movie plays with Ellie as an adult, fundamentally she's a child at the very beginning; she goes from being a naïve scientist to one who has a great picture of what the world is about. As she finds more clarity in life, we do also in the imagery. Overall, the beginning has softer images with more filtration versus, while the end of the picture, in Washington D.C., has the sharpest images."

Some of the stocks used on the film were dictated to Burgess due to their compatibility with the effects work, executed primarily in the digital realm by Sony Pictures Imageworks, under Ken Ralston. Kodak's 200 ASA 5293 became the stock of choice for any scene involving bluescreen effects. Notes Burgess, "Sometimes we changed film stocks for a visual effects shot that would be cut into a production shot, and dropped the ASA down a bit [to compensate] for the manipulation that would occur later, when, in a sense, you lose that generation [of grain]. It's said that with digital transfer you don't lose anything, but I don't believe that's true, which is why I've gone to the effort to use 65mm. You always want to use as low an ASA as possible for visual effects, because as you manipulate images, the sharpness and grain structure changes. The 5248 is the most bulletproof of all the stocks when it comes to manipulation, and the 93 is next in line. 5245 is great for that as web, but the 48 and 93 cut together better, which is ultimately why I ended up going with them."

Watching the Skies

Contact's 99-day shooting schedule entailed an enormous amount of location work that took the project's crew all across the North American continent. In the film's first act, Ellie is employed by Cornell University at the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico; the production shot at the actual site for two weeks in January.

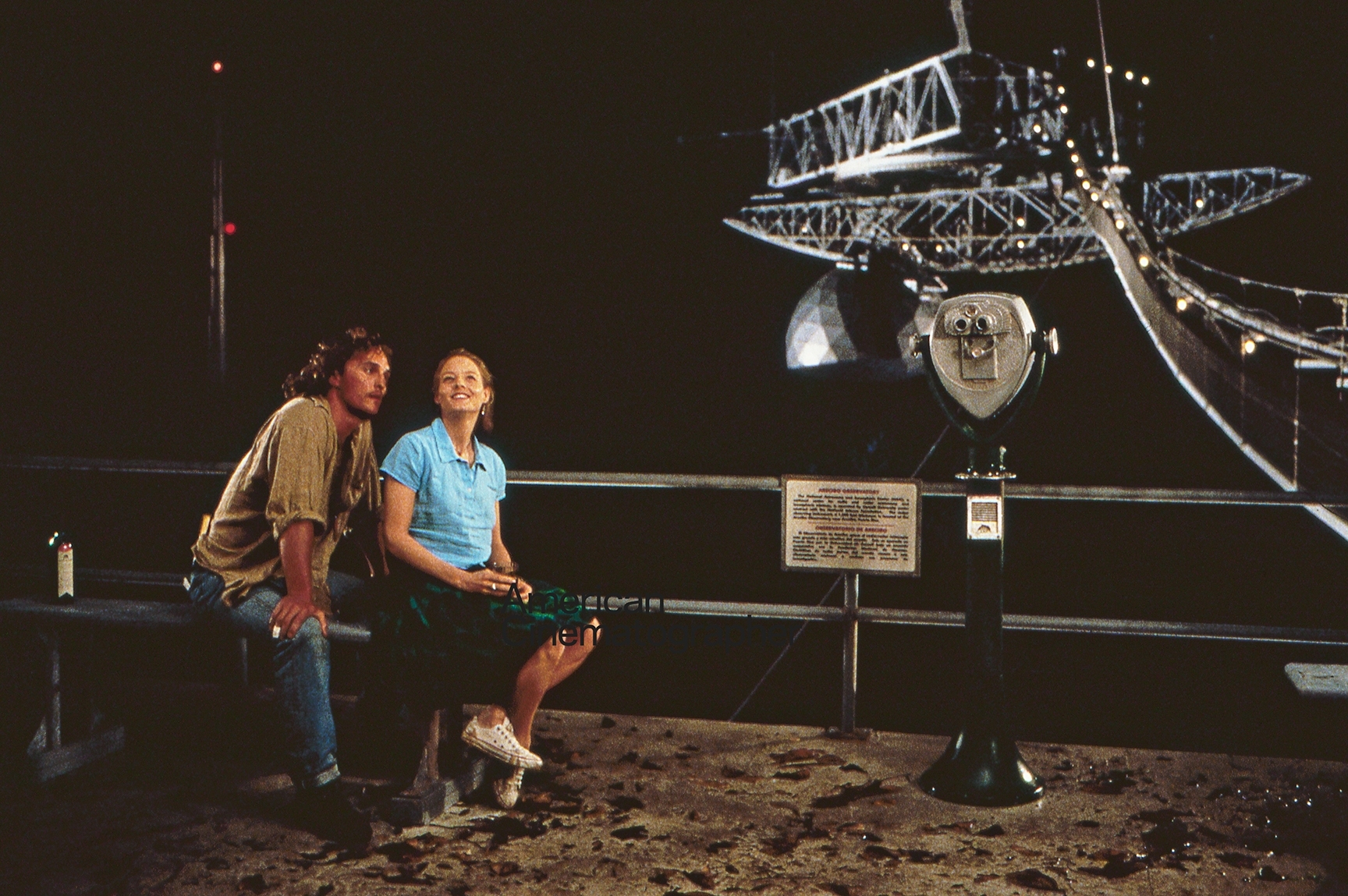

A romantic, nocturnal interlude between Ellie and guru Palmer Joss (McConaughey) on an observation platform above the dish required illuminating the telescope's entire perimeter. But the Arecibo dish — the world's largest — is shaped differently than the traditional radio telescopes: in this instance, the suspended receiver points down into a giant, motionless concave dish that is built into the landscape. Thus, the actual telescope had to be lit mainly from surrounding areas, such as the parking lots carved into the sides of the adjacent mountain tops. Burgess credits the skills of gaffer Steve McGee, who rigged Dinos, 12Ks and 18Ks around, across and below the telescope for four consecutive nights prior to the shooting of the scene.

Says Burgess, "You really try to get some detail in the background, but it's difficult because everything is dark green — it's amazing how many lights I had to put in [the surrounding jungle foliage] to get an exposure [with the 5279 stock]. The dish structure itself didn't have a high reflective quality either. We actually surrounded the inside of the dish with HMI Pars and shot them up from the center out to give the dish a spoked structure and take the flatness away. We raked the edges of it, along with the greenery of the jungle, to etch out a little bit of the detail. We then lit the whole top part of the telescope from the bottom up. We put a string of 60- to 75- watt globes on the railing to create an edge that would give depth to the frame.

"The trick with night exteriors is that the light needs to come from the sides and the back to create the modeling and the shape. When you're shooting in that direction with a wide lens at night, the question is where to put the lights. It's hard to get high enough off the top of the frame, and by the time you get around to the sides [of the frame], the light's too flat, so you've got to hide your units within the shot. There's no such thing as a Musco Light in Puerto Rico [the equipment necessary for this scene had to transported from Florida by barge], and even if there was, where would you park it to light the dish?"

Capitol Gains

After Ellie's grant money is revoked, she leaves for Washington D.C. in search of corporate funding for the project. This quest for capital in the capital brings Ellie to an ultra-modern boardroom on the top floor of a skyscraper. Burgess shot this interior on 5248 to achieve stronger contrast for the cold, stark aura he sought for the corporate setting. But since the space was some 12 stories high, the cinematographer had to illuminate the room from the roof of a building across the street. He threw light into the boardroom with 18Ks, a pair of 10K Xenons and multiple 7K Xenons.

Burgess also made efficient use of the Trimble for this setup. "I had to figure out how long we could actually shoot in the direction of the windows before having to finish another way once we lost the sunlight," he says. "I used the Trimble to figure out where the sun was going to be all day, and to see how much sunlight would actually be hitting the face of the building. So in the morning, I had my reference of what the exposure of the building was in relationship to the subject. When we were shooting against windows, we had to control the outside, but still had to try to make everything balance, because we were shooting there the entire day.

"Before we shot, I got up on top of the building and looked at the horizon — there wasn't a cloud in the sky, so I knew I had sunshine until mid-afternoon. Then, of course, halfway through the day, the clouds came out of nowhere. Because we started out bright with the sun hitting the back walls, and then ended up with a cloudy day, I had to take down the inside exposure to balance it to the outside. 'To keep it matching, I left the building at the same exposure and brightness level. I had to drop the exposure down to match the building enough in the relationship between the face and the foreground, and the building in the background. "It's difficult to work 12 stories up, because it's tough to light from the ground. It's always much nicer to have light coming in from the windows so that you can model things and give them an edge — especially in this case, since we wanted to create such a stark look."

Tackling the TransLights

Interiors of the film's various control rooms — the Arecibo facility, the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope facility in Seccoro, New Mexico, and NASA command in Cape Canaveral, Florida — were all shot on stages with windows backed by huge TransLights [transparency blowups of still photos] created months in advance. The TransLight for the mock-up of NASA's command center, for instance, had dimensions of 120’ x 38’ and was backlit with 132 5K Skypans in order for Burgess to achieve a stop of T11. "Properly exposing TransLights is a real key to making them believable," he says. "They need to be overexposed a couple of stops. The backings are made to withstand an enormous of amount of light, so you can keep stacking the fixtures to bring up the intensity, and make it as bright as possible. I used a white net [black netting was used for the faux NASA] in front of the TransLights to take out some detail and contrast, and to wash them out a little. You've got to give the audience enough detail so that they know what it is, but it's a fine line. If you give them too much detail and too much exposure, they'll see that it's a photograph."

There were instances when the composition of a shot necessitated trading the oversized transparencies for a bluescreen. Says Burgess, "The scariest thing about a daytime exterior TransLight is keeping it looking realistic. If we got to a point where the shot was too wide, there was too much depth of field, and we could see too much of what was actually outside, we'd roll that TransLight out and do the shot with bluescreen."

The production's most complex use of a TransLight occurs after Ellie hears an alien communique for the first time. In pure Zemeckis style, this sequence appears as one continuous pass, even though its various segments were filmed some four months apart. The scene starts with a dusk exterior of the excited astronomer driving to VLA headquarters, all the while chattering into a walkie-talkie to her colleagues. She parks the car in front of the building, runs inside, sprints down a hallway and executes a few turns before entering a revolving door.

At this point, the location work at the actual VLA site ends, and the shot continues on a Culver Studios set. Ellie sprints up some stairs and cruises down another hallway into the constructed VLA control room. Once inside, she places her walkie-talkie radio on an active computer monitor. The camera finally closes in on the TransLight as one of the dishes is locking into a position from which it can track the alien signal. The shot ends with the monitor's confirmation that contact has indeed been made.

While 5277 was used fo the first half of the shot, Burgess had to switch to 93 for the studio section, since the shot concludes with a digitally manipulated image of the radio dish.

The production only had five to ten hours to shoot at the VLA site per week; researchers using the facility have their dish time booked years in advance. Therefore, the first section of the shot was filmed during dawn and dusk over five consecutive days. It was done using a Beaumont VistaVision camera on a Steadicam operated by Mark O'Kane, beginning from a high angle as he stood up atop a Titan crane. As the truck pulls up, the Titan lowered and O'Kane stepped off, trailing Foster as she entered the building and ran down the hallway through spotty pools of light (created by 2K softlights) cast down from the ceiling.

For the second half of the shot, filmed on the control room set, Burgess had to contend with a TransLight which demanded less backlighting, since the transparency displayed a dawn setting. Balancing the room's ambience with the TransLight and the computer screens was also a concern. Burgess expounds, "In that type of situation, you have to expose it to balance; you can't blow it out and lose the detail that way. So you have to get the TransLight photographed at as close to the proper time of day as you possibly can. My biggest problem was that the sky in the TransLight photograph was way too blue. The challenge here was to remove enough blue from the TransLight to make it match the reality of the day that we shot at the building [on location]. We went to full CTO on the Skypans to suck out some of the blue.

"The computer screens and TV screens are only going to be what they are," he adds. "You can only manipulate them within a stop one way or the other, so you have to be in a ballpark with those elements. A lot of times you have to work backwards from them to get the TransLight to work with the computer screens, the [lighting of the] actual location, the f-stop that we're trying to match, and the film stock from both places."

Foray into the Final Frontier

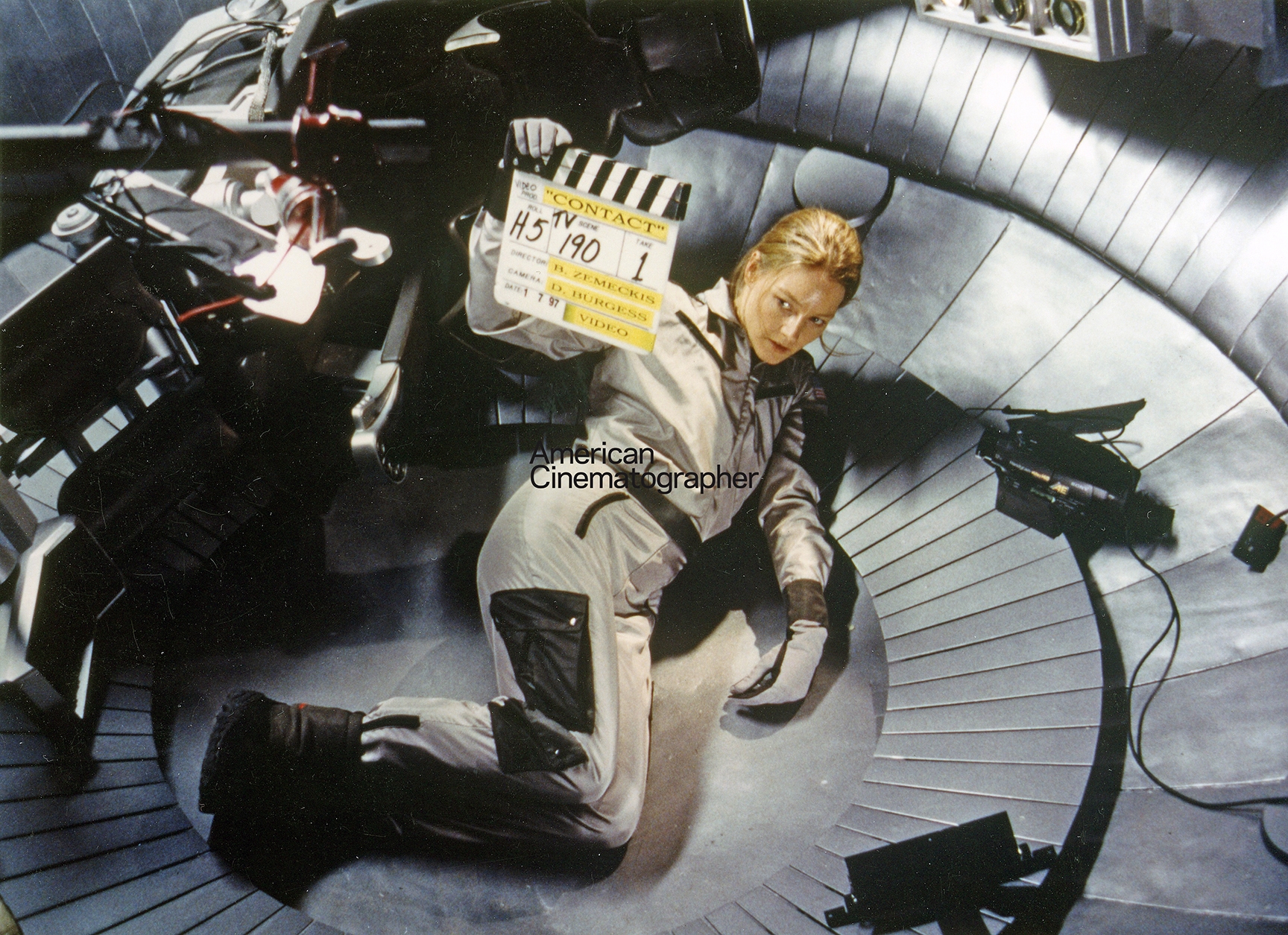

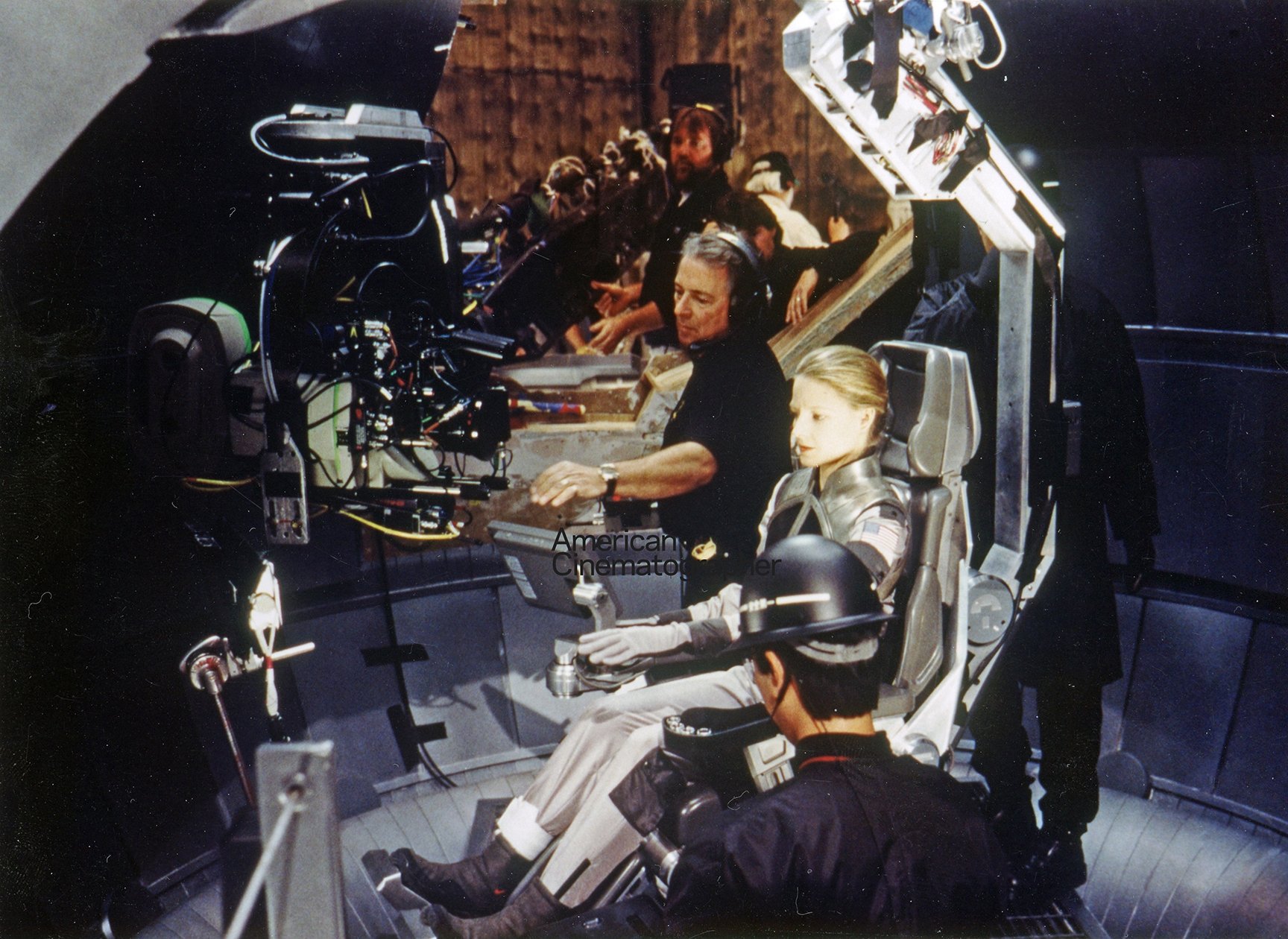

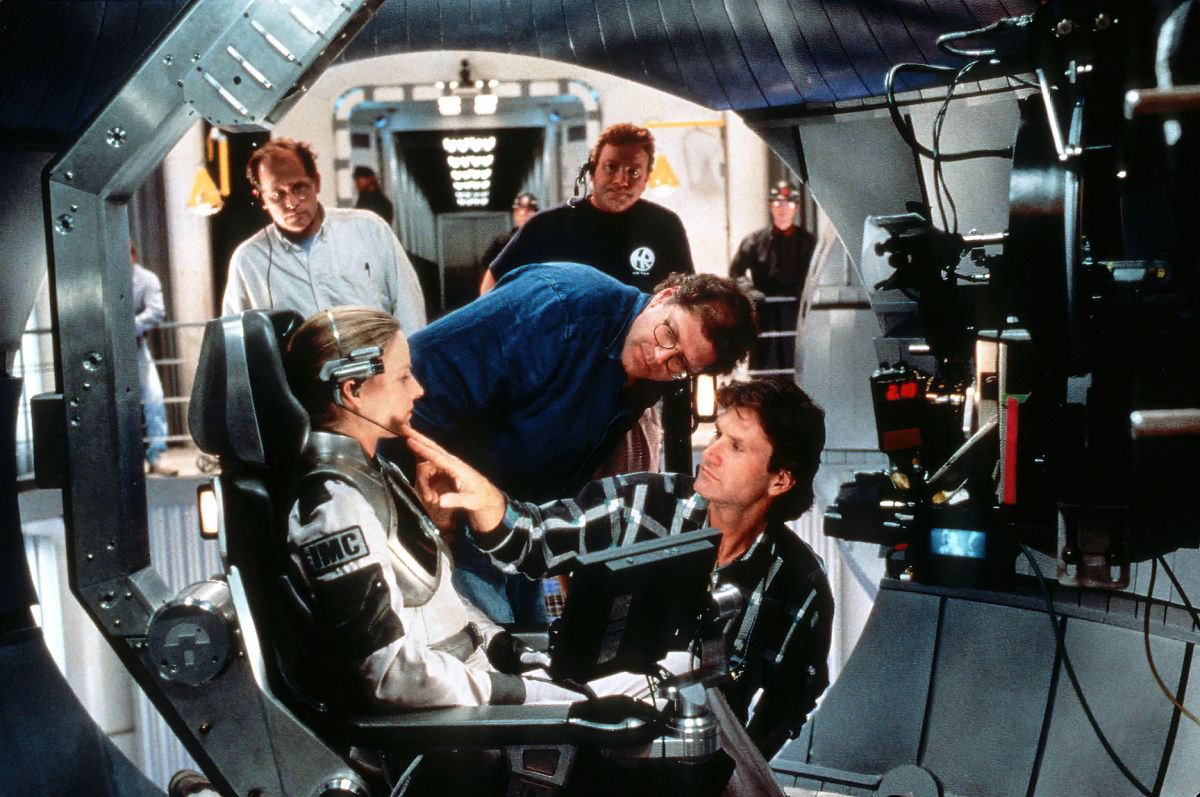

The "Vegan" spacecraft in which Ellie travels is an enclosed spherical pod equipped only with one chair suspended from a bar fixed to the ceiling. A laptop-sized computer attached to the seat's right arm serves as the ship's control center. The pod interior was illuminated from above with three dimmer-controlled MR16 bulbs secured to the top of the chair. Burgess fitted the laptop monitor with tiny fluorescents to provide a glow from below when the computer face itself was off-camera.

The filming demands of the scene required the construction of three different pods: a fully encased one resting some 30 feet above floor level, and two auxiliary versions only 10 feet above ground level, which could be pulled apart in sections. The various pods were also outfitted differently. Earlier in the film, Ellie's mentor, David Drumlin (Tom Skerritt), takes an ill-fated voyage in a NASA-constructed prototype which sports a stripped-down, industrial-type layout; conversely, Ellie's pod, constructed by an amorphous Japanese conglomerate, is of a more polished, high-tech design.

During the launch, the ship's external rings oscillate rapidly to produce the magnetic energy needed for its liftoff. Burgess' task was to conceive a light source that mimicked these gyrating energy waves. He notes, "The arm [of energy] comes over very slowly when it starts at 40 percent. But the ring deployment keeps getting faster, so by the time you get to 90 percent, it's a really intense strobing effect. We had to take a giant source of light, and then create a chase effect so that the light turns on and off in as if a blade was crossing over it. And we also had to find lights that would go on and off quickly. What we worked really well were giant banks of MR16s. Because the bulbs are small, they actually react more quickly to dimmers: the larger a light is, the slower it reacts to the on-and-off cycle. We brought in a computerized dimming system to control all the lights and create the pace of the on-and-off period. Then we could set it for the particular stage of ring deployment that was being shot [on all three versions of the pod]."

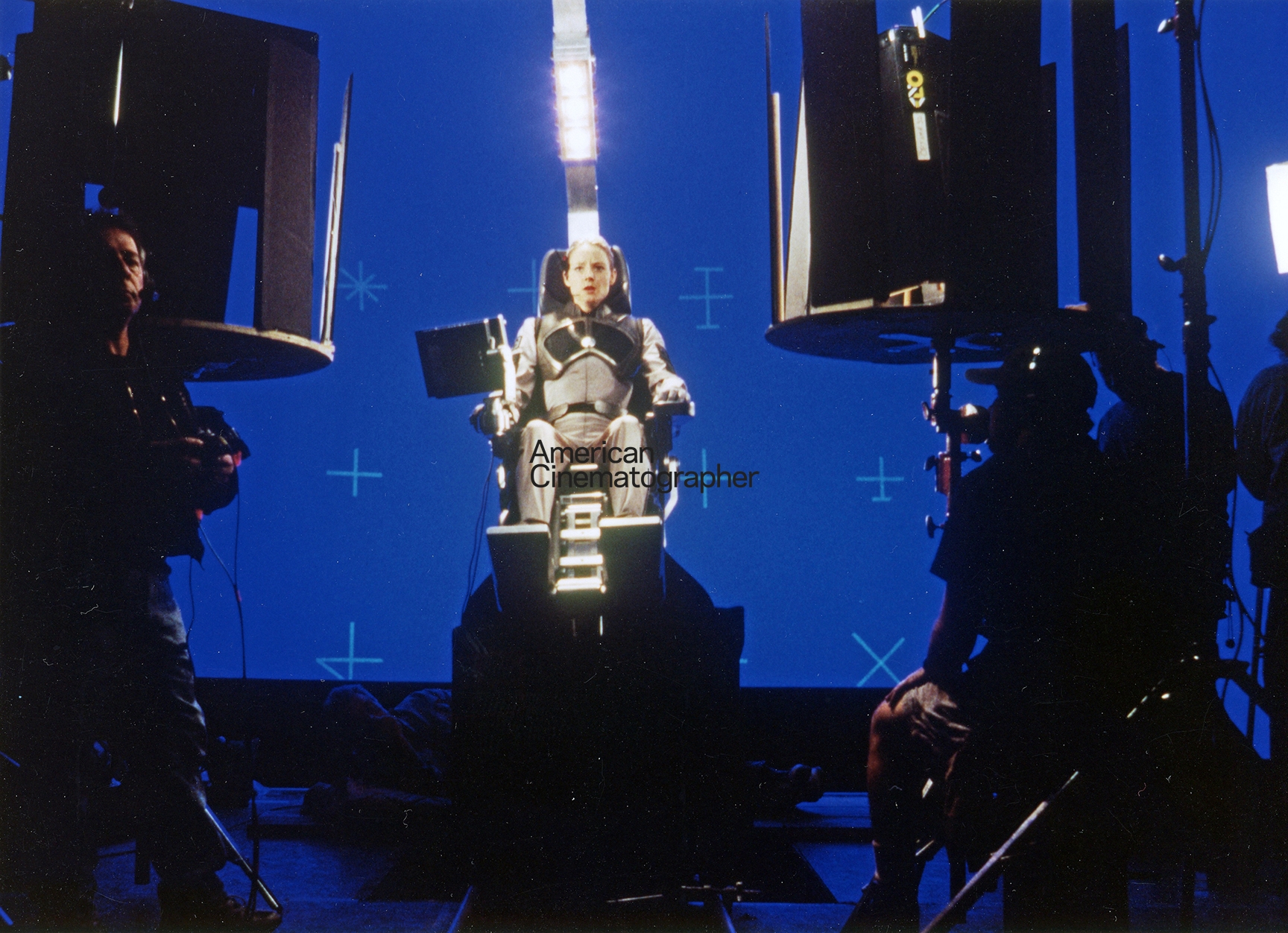

The craft's flight is seen only from Ellie's perspective, even though the pod itself has no viewing portals. Vegan technology, however, allows her to "view" the stellar surroundings by having part of the inner hub "dissolve" in accordance with Ellie's line of sight. The "portal" was realized by placing a patch of bluescreen — into which visuals could be composited — along the craft's inner wall.

Analyzing this subjective take on space flight, Zemeckis offers, "Ultimately, the only way I could do this scene was from Ellie's point of view. The camera never goes out into space; we always present what she can see from wherever she's looking at the universe. It would make absolutely no story sense to show it from any other point of view. And it couldn't be from anybody else's POV because I don't think there's anybody out there. It would be ridiculous to put the camera someplace without knowing whose POV it represents."

To convey the illusion of movement during Ellie's voyage, the production team first devised a "color overview" of the universe extrapolated from known astronomic knowledge. According to this chart, Ellie's pod passes through a few wormholes, flies by Vega and an unnamed ice planet, and eventually ends up in what is referred to as "the golden center of the universe." Each celestial body or phenomenon was afforded a color scheme which was matched to specific gels. As the pod enters the Vegan atmosphere, for example, the dominant hue is blue; Burgess used a progression of RoscoLux gels: lavender (57), pale violet (355), light rose purple (47) and full blue (3202).

After conceptual drawings of these situations were created, corresponding video images were cast upon Jodie Foster's face with giant video projectors from Background Engineering. Illumination from various fixtures — strobes, flash bulbs, arc lamps and spinning merry-go-round lights — was mixed with the video imagery. Mechanical effects also lent to the sense of motion. One version of the pod chair shook violently, while another was designed to operate upside-down. A weightless effect was created by placing Foster on wires and by rotating the camera as well as the pod. In addition, camera speeds were frequently ramped from 22 to 12fps.

In keeping with the existential tone of Ellie's flight, her voyage ends on a picture-perfect beach which she once envisioned as a child — an illusion the Vegans have generated to make the intrepid scientist comfortable in their unfamiliar milieu. The aliens then communicate with Ellie by taking the form of her long-deceased father, Ted (David Morse). Burgess shot this encounter on a set lined with a bluescreen fitted over three walls and the floor. He felt that this strategy was more effective than working on location, since "the beach had to become surreal. It had to be a separate image that could be manipulated to create super-vibrant color. The sky is not going to be perfect, because at the very top it blends into deep space. As Ellie reaches out to touch things, the image responds with a slight rippling effect.

"We used a 20K as a motivated sunlight source, even though there really is no sun [in the Vegans' hologram]. The rest of the backlights are 10Ks, and the bluescreens were all lit with Super Blue Kino Flos. Down on the floor, I used a lot of white board to create the beach's reflective bounce from below."

Burgess is currently shooting commercials in his hometown of Los Angeles. He says that even though Contact was shot on a grueling schedule, he found the production to be a rewarding challenge which allowed him to draw upon his extensive background in second-unit cinematography. "That experience was invaluable, because I got to shoot action sequences at night with multiple cameras and huge lighting setups," he says. "The organizational skills that you develop to make those big setups work really helps on a movie of this scale.

"Plus, you have to understand how to work so many different tools — Lenny arms, Libra heads, Titan cranes, Steadicam — that you tend to use a lot for second-unit work. You have to be familiar with the equipment needed to accomplish the shot — especially when you work with Bob Zemeckis, because inevitably he's going to start a shot as grandly as he can and end in a tight close-up, or vice-versa."

On March 3, 2024, Burgess was presented with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award during the 38th Annual ASC Awards ceremony.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.