Who Framed Roger Rabbit? A Crew of 1,000s, That’s Who!

Director of photography Dean Cundey, ASC, details what it was like filming this revolutionary project in England and the difficulties that came with it.

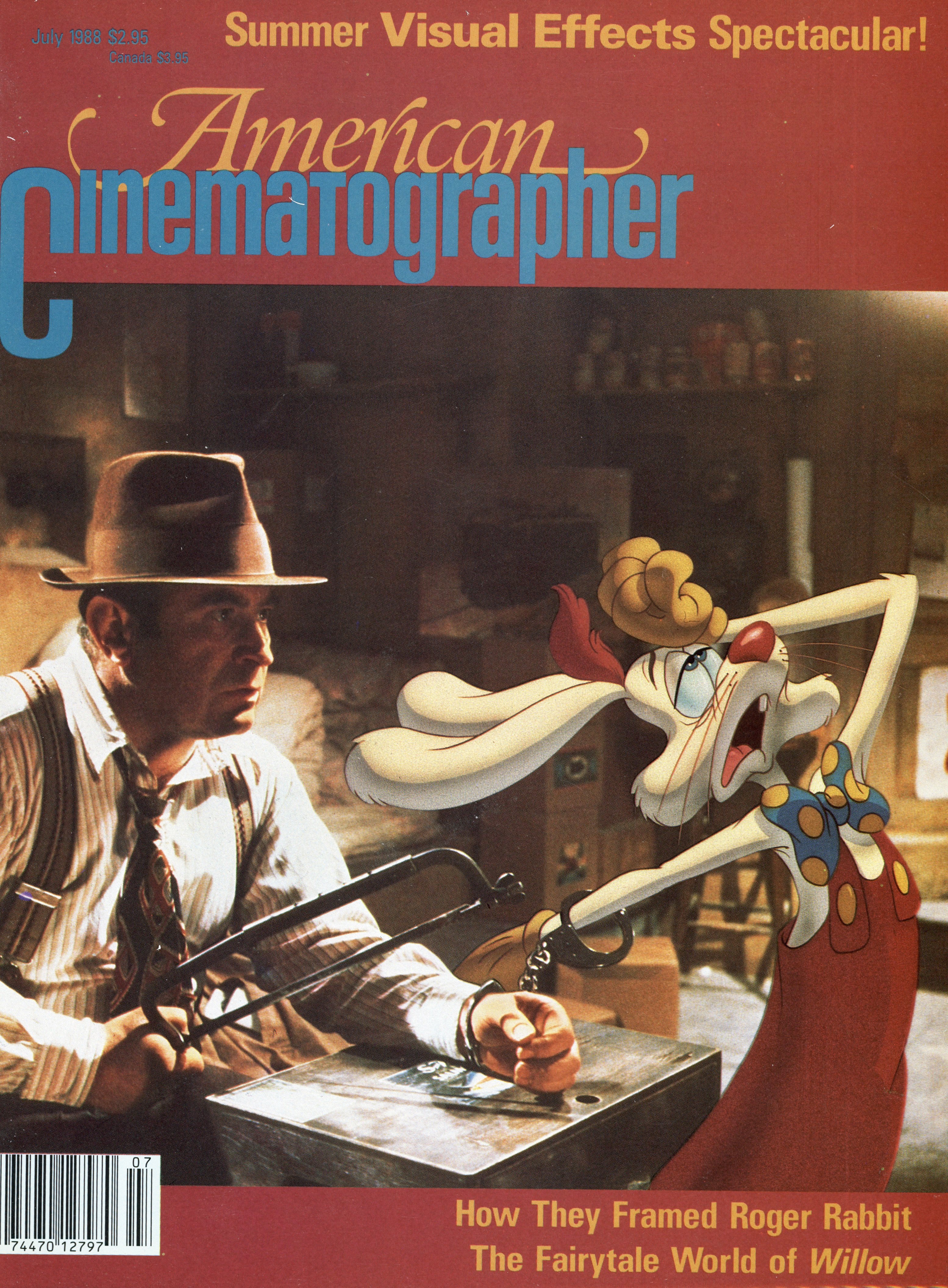

Who Framed Roger Rabbit is not an easy show to describe. To say that it combines live action with cartoon animation, while truthful, doesn't begin to say to what extent or with what skill this has been accomplished.

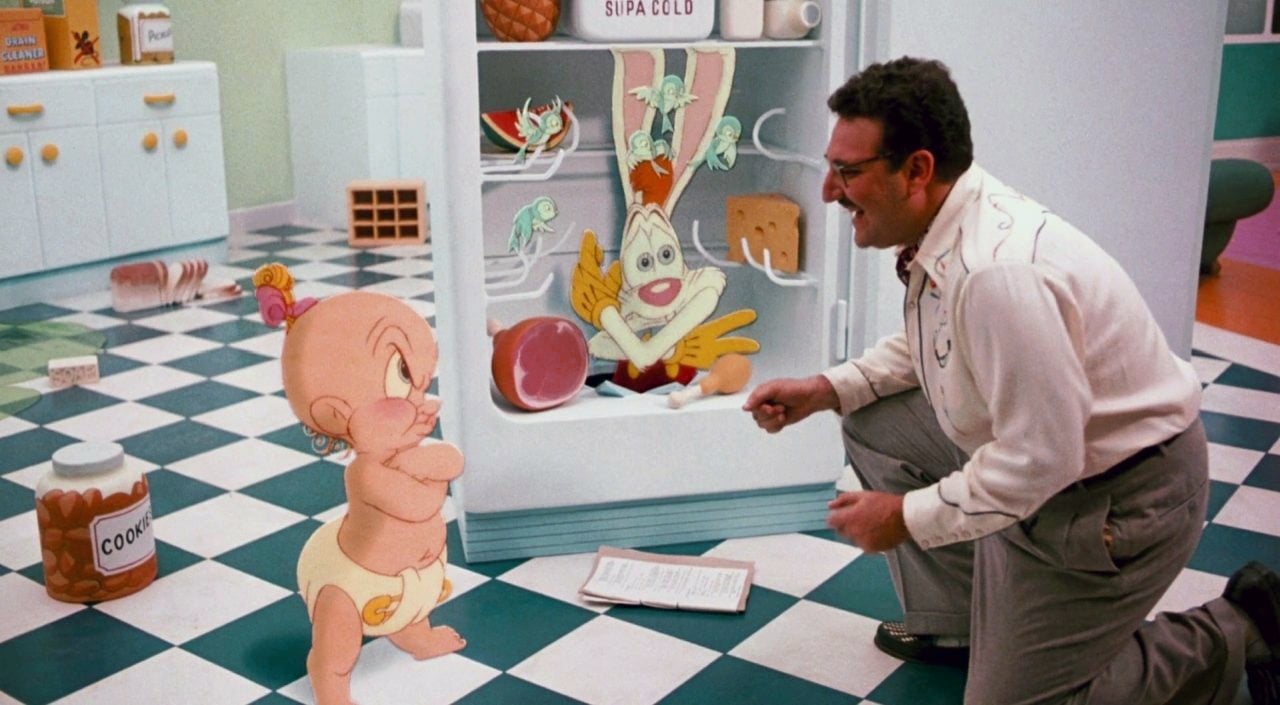

The basic idea isn't new. Max and Dave Fleischer did it with their Out of the Inkwell cartoons in the 1920s. Walt Disney put his cartoon creations into scenes with human actors in full color in The Three Caballeros, Song of the South, Mary Poppins, and other well-loved shows. Who can forget that great sequence in Anchors Aweigh wherein Gene Kelly performed a dance routine with his fellow MGM stars, Hanna-Barbera's Tom and Jerry? More recently, some notable work in the area has been done in television commercials.

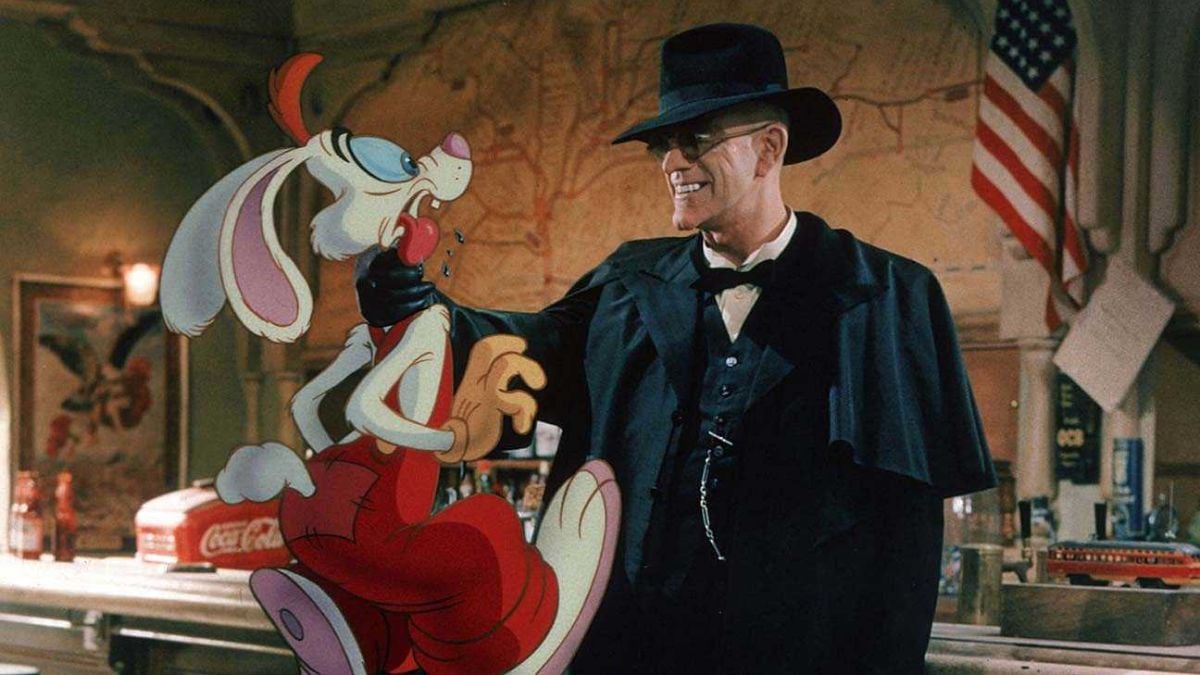

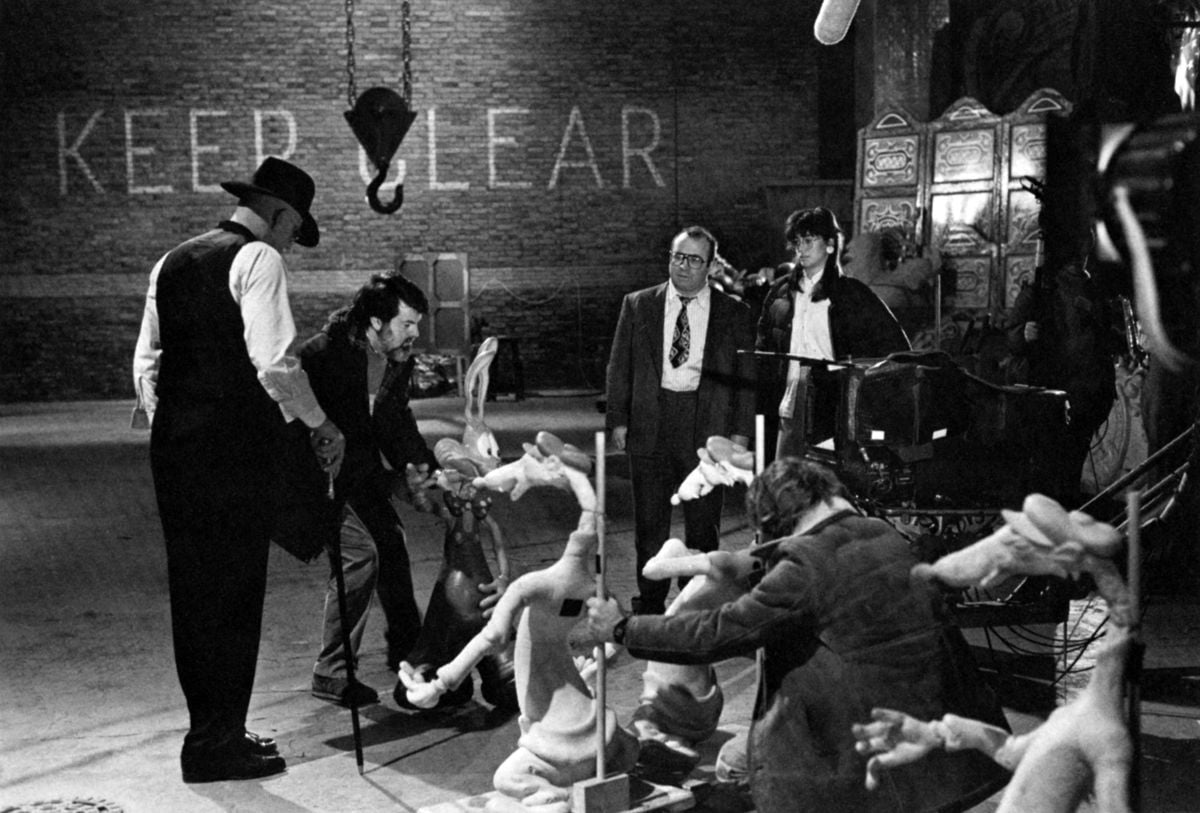

Yet, it will have to be admitted, these landmarks of filmic delight are almost primitive, technically speaking, alongside this collaborative effort of two entertainment giants, Disney and Lucasfilm. Heretofore, there has been a definite demarcation between live-action characters and cartoons: the human actors are real and the cartoon characters are strictly from fantasyland. In Who Framed Roger the Rabbit the audience must suspend its disbelief long enough to accept the idea that the cartoon characters are as real as Bob Hoskins and the other flesh-and-blood co-performers. It's a comedy-murder mystery-chase thriller, done on a vast scale and filled with homages to the great cartoon creations of the past. Its realization was possible only through the determination of a lot of talented professionals to broaden the parameters of cinematic expression.

A key member of the team is its director of photography, Dean Cundey, ASC, whose tantalizing descriptions of Roger in various stages of production make the story of this film a fascinating one.

"It's a unique project," Cundey understated. "Technically, it's an English production. It was financed by Walt Disney, Ltd., a British firm. Most of the principal photography was done in England with a predominantly English crew, many of whom worked on Lucasfilm projects such as Indiana Jones. It's about Hollywood in the 1940s, so we had to recreate Hollywood in England, even bringing in palm trees from Spain. We did some exteriors in Los Angeles, and we did a lot of bluescreen work in San Rafael, but the United States actually was a distant location for us."

Cundey began preparation in England in August of 1986, returned to the States for three weeks in November, and went back before Christmas, remaining to do the British Lion's share of principal photography. Two production units worked around the clock at Elstree Studio until the end of April 1987. There was a three-week shoot of street action in downtown Los Angeles, and more months of bluescreen effects photography at Lucasfilm's Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) facility in Northern California. Altogether, Cundey was involved in Roger Rabbit for almost two years.

"After our initial talks, we adopted the general policy to do everything exactly as if the cartoon characters were alive, in the way we normally tell a story in a film," Cundey recalled. "With minor exceptions, we were able to do that and the film benefits greatly. I read an article in the newspaper recently which stated that the animators were concerned with the fact that the camera moved so much, but most of the animators I've talked to said that the great boon of the picture is that we didn't adapt our technique to an easier, more conventional way."

Cundey was enthusiastic — mostly — about working in the British studios. "The English, during the development of their film industry, have evolved a somewhat different technique than the American system regarding the personnel they have and how they work. It was interesting to adapt to their ways, taking the various job assignments and getting them done in a little different way. We saw that some of them could be extremely useful in the American system if they were applied to it.

"In this country, we have two groups of technicians: the electricians, who set up and operate the lights; and the grips, who handle flags and nets for controlling the light, set up scaffoldings for elevating the camera and lighting equipment, and mount the camera in various places such as on automobiles.

"In the English system," Cundey noted, "there are no grips as such. They have a camera grip in charge of moving and taking care of the camera, but all the other jobs that the U.S. grip would do are spread out among the electricians and a group that they call 'riggers,' who work with scaffolding pipe. The setting of flags, nets, scrims, et cetera, is all done by the electricians. Where we would have perhaps four electricians and four grips, they hire more electricians — say, six — so they'll have enough crew to set nets and flags, and two riggers to handle a lot of the other construction work. There are the same number of people on the crew as we have, but the assignments and job descriptions are different."

The pipe rigging system, Cundey learned, is highly efficient. "It's amazing what the riggers can do! For my next show, Road House, we're building a set in a warehouse with no chance to mount catwalks above the set as we could in a studio, so I'm going to adapt the English pipe system of hanging lights. So I'm already taking advantage of some of the things I learned in England."

"We had an extremely good art department. The sets were built using slightly different techniques in construction and painting. I gained an understanding of why European pictures look somewhat different than American films. They use fewer light control devices, such as nets and scrims, than we do. Only recently have they started using some of the things we use because some of the English technicians have traveled to the U.S. to do commercials and when they worked with American directors of photography they'd adapt some of the American techniques. More typically, they use just lights, and the European pictures reflect that in different looks."

Cundey described how the duties of the English cinematographers differ from those in America: "The lighting cameraman does the lighting and the operator works with the director to select angles and so forth. Because our director, Bob Zameckis, was American and I brought my own operator, Ray Stella, and my VistaFlex assistant, Clyde Bryan, we worked essentially in American style and adapted that to the English crew system. Ray Walthour was our chief lighting technician.

"We had an English second unit and sometimes a third unit that would often follow behind us and they shot a lot of the effects sequences and pieces that we needed. Heading that was Paul Beeson, an excellent English cameraman, so we had a top-quality second unit. It was interesting working with Paul and watching how a purely English system worked.

"Elstree," Cundey said, is "a very interesting studio. Lucasfilm has been using it for some years for their Star Wars and Indiana Jones shows. We looked around at some of the other studios because we needed a very large set at one time, but we ended up building the set in an old deserted factory building in London. Working there was probably the hardest part of the show, partly because it was so cold. The winter was one of the coldest they've had in about 40 years, getting down to 15 to 20 degrees, and the building was not insulated or heated. We were working early mornings and throughout the day with heavy jackets on, and we were on that set for three weeks. The sequence for which it was used is the big climax of the picture and it involves a great deal of effects and action. Because the interior gets destroyed gradually, the second unit had to work almost simultaneously with us. We would show up at seven o'clock in the morning and work until six or seven in the evening; then, as we were leaving, the second unit would show up and they would work all night — when it was even colder! — until seven in the morning. The inside of the factory and our VistaFlex camera were busy 24 hours a day for at least two weeks and the lights we rigged were burning constantly. Some of them were never shut off except when it became necessary to change a burned-out globe.”

The lighting equipment, Cundey found, was not markedly different in function than what he was accustomed to, although most of the units were not the same ones that are used most commonly in the United States.

"They substitute different but comparable units, frequently the IANIRO products from Italy. The HMI lights were either Arriflex or LTM and are French. Most of the equipment is somehow similar to what we're used to as regards the output of light, such as 1K and 2K. They've begun to build grip equipment that we're familiar with — century stands, nets, et cetera. They have a few of their own inventions that were quite useful and, like most motion picture equipment, they have unusual names. They have, for example, "onkabonks,” which are a series of pipes that plug together and are used to support lights. They come in lengths of anywhere from six to about 18 inches, and each section can be put together with others and used to raise or lower a light from a mounted position, whether overhead or on the floor.”

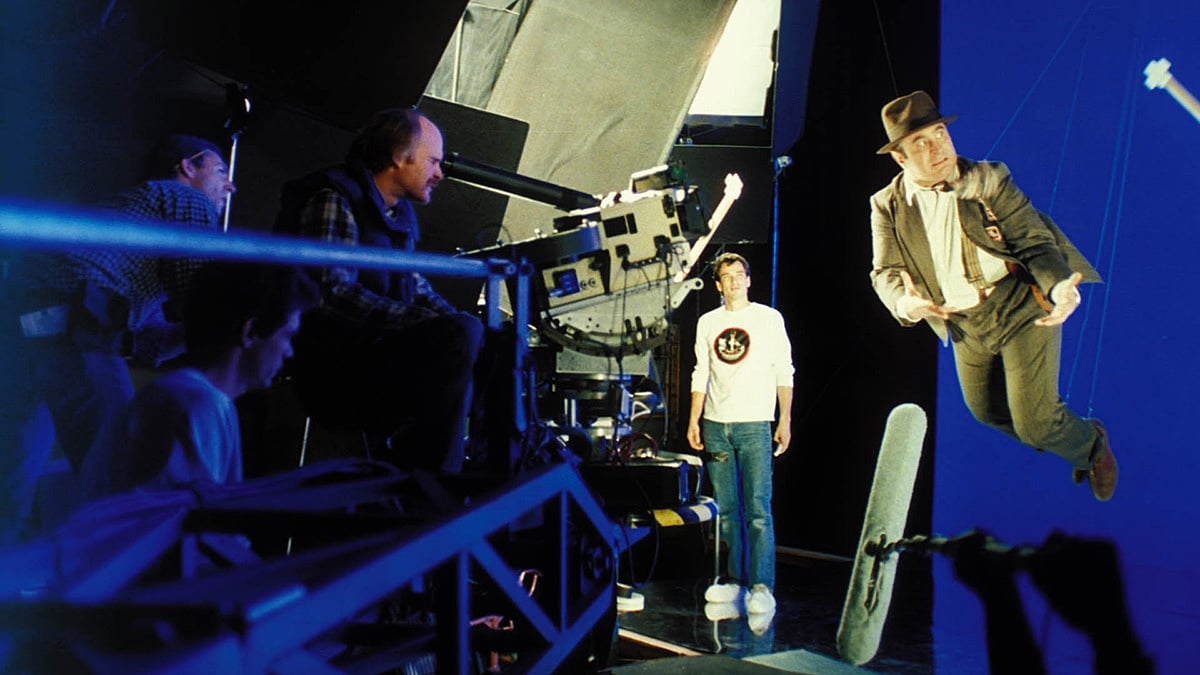

Although the picture is being released in standard 35mm format (as well as in 70mm blowups for some key locations), about 80% of the English footage was photographed in VistaVision because it included bluescreen elements that eventually would be composited with animated cartoon elements. This permits optical duping of the highest quality, the larger size of the original negative compensating for any generational loss.

a bluescreen on stage at ILM.

"I learned to speak English as well as American,” Cundey said, "but they still use Cockney rhyming slang a lot, which can be confusing. It was fun because Hoskins is Cockney and a lot of the crew are either Cockney or used the slang, so it became a cultural experience learning to understand when they were talking.”

For the street scenes shot in downtown Los Angeles, two blocks of Spring Street between Seventh and Ninth Avenues were revamped to resemble Hollywood in the 1940s. "They built two red cars — like the trolleys that used to run through L.A. — re-did the facades of a large number of buildings and added signs," Cundey revealed. "We had the trolleys and a lot of vintage cars running through the streets. A car chase takes place there, and it's interesting in that the car Bob Hoskins is driving is an animated car. They built a small motorized car — almost a go-cart kind of thing — in which to move Bob around rapidly, and then the animation is placed over the top of that. Roger Rabbit, who is riding with Bob, is placed over that also.

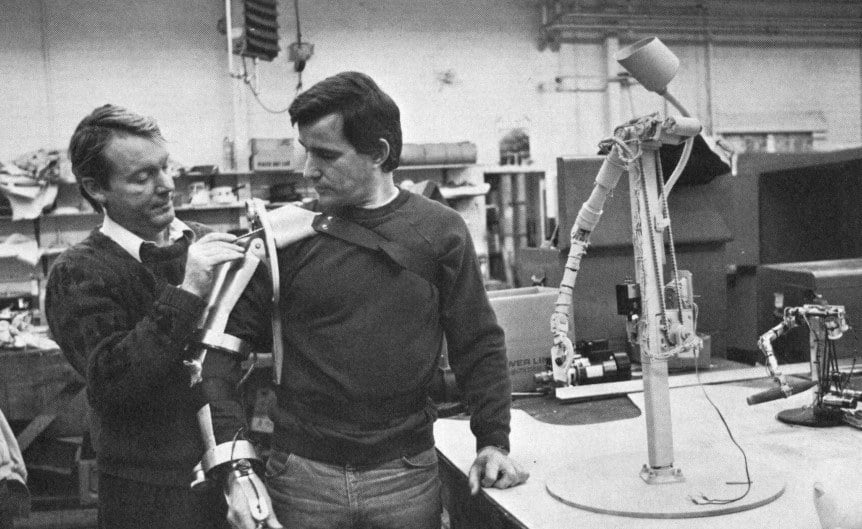

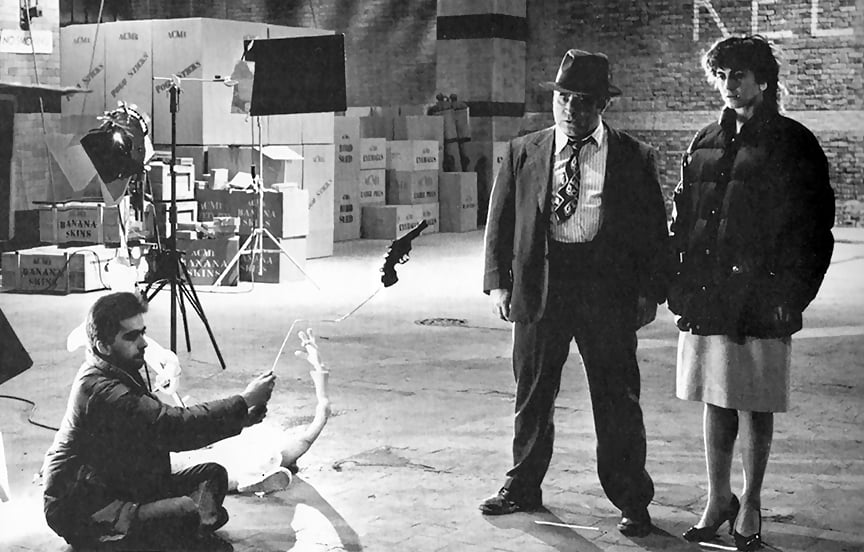

"We built full-size, bendable rubber characters to use as stand-ins to help with the lighting and staging. Each time we photographed a scene we would always do one take using these large, poseable figures, which were built for principal animation characters, such as Roger, the weasels, and a couple others. These proved to be extremely useful devices because the operator was able to see their sizes in relation to the actors. The director or I would then move the character through the scene as it was rehearsed so that everybody would understand what the action was and where the character would be moving. The operator would then be able to see how fast it moved and decide how to compose. Then, when we shot the scene, we didn't use the figure, and the operator would have to just imagine where the character was in relation to the dialogue, which was being delivered by an off-camera actor. The actors in the scene were able to do the rehearsals with the figures, visualize what the action was going to be, and then during the actual take they could draw upon memory what the figure had done when brought through by the director."

Last fall, while Cundey and visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston were working on further bluescreen shots at ILM, American Cinematographer observed some of the unusual methods being used for the first time in depicting Roger's adventures.

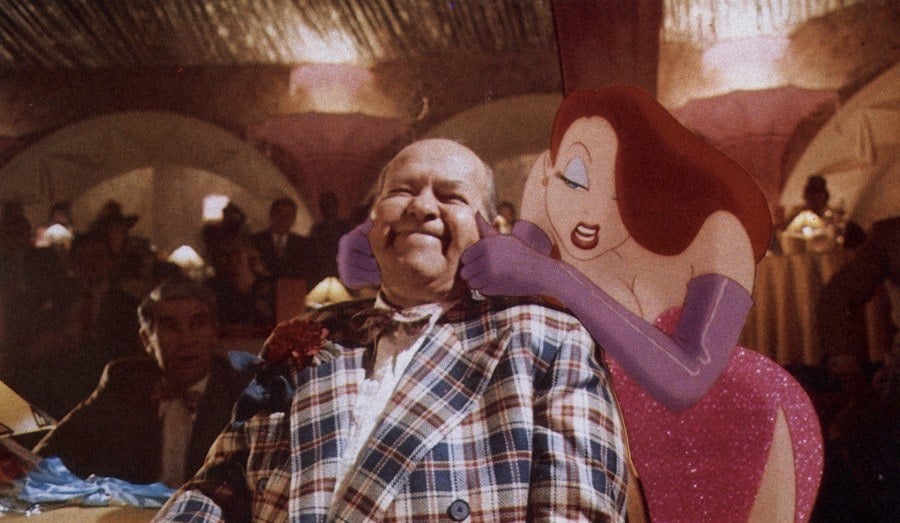

Hoskins and some of the other players were there, costumed in styles of the 1940s. Remarkably, Hoskins' Chicago accent was perfect, with no hint of his British heritage in evidence. Another actor was heard but not seen — the exceptional nightclub comedian Charles Fleischer, who provides the voice of Roger. It was strange to see Hoskins sitting in a nonexistent car in front of a brightly lighted bluescreen while talking to a big, rubber rabbit whose raucous voice came from off-camera.

Cundey introduced Bill Frake, an artist-technician who was working with swift efficiency at a table on the stage. "Bill is doing layouts as we set up this whole video compositing thing and the bluescreen stuff you saw, which we will composite here," he explained. "But then he has to figure all the perspectives and vanishing points and sizes of doorways and stuff like that, so I'm hoping to spend some time in that area working with him. Having lit the scene" — he indicated Hoskins being positioned for a bluescreen setup — "I have to designate on the backgrounds where the lighting sources are and locate fixtures, things like that."

The crew took some time off from the feature to photograph a commercial for Diet Coke on the smoke-hazy nightclub set. The tables were set up on tiers and all the players were dressed and made up in the styles of 1947. The resemblance to the paintings by Elvgren, Sundblom, Loomis and other great illustrators whose work graced the Coca-Cola posters and ads of the period was striking.

The daily screenings were intriguing, being a mixture of scenes in various stages of completion. Some were live-action blue screen shots to which optical effects had not yet been added. In these Hoskins, often rim-lighted in yellows or reds was seen acting with the invisible but noisy rabbit. Sometimes the camera would swing out to take in areas of the stage outside of that which would be seen in the final composites, panning across crew members and equipment to give the animators help in planning movement. Others were live-action shots that had been test-composited with animation still in the penciling-in stage, the slimly graceful lines of the artists' work swirling smoothly like ghost images over the scenes. Some composite tests in later stages showed finished color cells acting in concert with Hoskins, but not all had been refined to the point of having sufficient density, sharpness (or softness) to create a convincing blend. Then there are the finished shots, which must be seen to be believed, in which all the details have been tweaked and polished to an astonishing degree.

The complexity of the technique employed throughout most of the picture made color timing of more immediate concern than usual. "Most likely the final timing will be done at Deluxe in Hollywood, but this is an unusual picture in that all the backgrounds are going to have something composited over them, whether animation or effects," Cundey revealed. "Early on, we decided we had to consider the end result very carefully because everything we were doing in pre-production and during production was going to greatly affect what was going to be done eventually. This includes even the timing, which normally isn't done extensively until after the negative has been cut. As we were working we had to consider the end result and almost think backward, always considering the post-production work involving all the animation of characters who were only going to appear later. We were shooting them, you might say, at the time of production.

"All of the work that has to be composited into the live-action that we've shot has to match and be consistent," Cundey emphasized. "On this picture, there are many shots that were done at varying times out of sequence during production. A lot of times they kept one shot out of this scene and another out of that one, so I went through the dailies with some of the guys from ILM and Steve Starkey, who is supervising postproduction, and we selected 'looks' out of existing footage even before it was cut together. If we didn't find any shots that looked proper as to color and depth, we went to the trouble of timing them then, so that there would always be reference pieces from which to work while doing the compositing. It's one of the few pictures where I had to time the picture before they even started printing anything.

"Now they've prepared a book of selected shots that they use for their optical wedging to get the color right, and anytime they get a composite for a particular scene they go to their reference 'swatches' and try to match it all to what was selected to represent that particular scene."

In mid-April, about two months prior to the scheduled release date, Cundey (who was by then involved in the making of another feature) reported that about 750 of the 1,031 optical shots had been completed. "They're now in a position to start cutting some of the negatives for the reels, and they want to run through the workprints. Over the next month or so I'll be meeting with them consistently to time the print as it comes out. Most of the time when you finish a picture you may have anywhere from three days to a week to look at answer prints and time them, but this will be probably spread out over a month or more.”

The varying needs of the production dictated the kinds of film stock to be used. All original photography intended for compositing was photographed in the eight-perforation horizontal VistaVision format, while the normal action photography was done in the regular four-perf format.

"We have probably run almost every kind of emulsion there is," Cundey noted. "ILM uses Kodak's 5247 for almost all their bluescreen stuff. They've been testing the recently introduced blue screen material, 5295, but apparently, it takes some readjusting of the handling of the timing and compositing until they get used to it, and they're still in the process of working all that out. We used the new 5297 daylight balance and some 5294 for some of the regular four-perf stuff — night exteriors and so on — and stayed with 5247 for most of the stuff that has to be composited.

"Inside the large factory at the climax of the film there is an extensive sequence where we didn't want to use 5294 but we didn't have enough speed with 47, so we used Agfa's 320-speed film, which ranges somewhere between 5294 and 5247. ILM had to re-calibrate their usual timing procedure because the color balance is a little different.

"I like the Agfa," Cundey added. "It's a different look. We found that the grain was finer than 94. The color is a little warmer and they found that when they composite it tends towards green, so they have to add more red to get it to match the Kodak. We used it in a different situation than we might if we were shooting a regular picture, so I'd like to try it further under regular conditions. When we were shooting in England and the question came up of what to use when we had to have a little faster film, most of the English guys I worked with had used Agfa. Paul Beeson, who did our second-unit work over there, had done quite a bit of work with it and he recommended it. We tested it and the guys at ILM checked it to see how it would go with their compositing work, and they found that, while the grain was not as fine as 47, it was within their tolerances."

The cinematographer and his crew were enthusiastic about the new VistaFlex camera, which received its baptism in the making of Roger. lt is decidedly different in appearance and in functional details from any previous camera. Cundey was involved in the design of the VistaFlex in collaboration with ILM technicians.

"Since the show is almost all effects, about 80 percent of what we shot was done in VistaVision," says to Cundey. "ILM had been talking about building another plate camera because the EmpireFlex — which is their small VistaVision camera [built for The Empire Strikes Back] — was being used so much. Then, when Roger Rabbit started to become a viable project, almost two years ago, I said it would be desirable to have a good production camera and they said they were thinking of building one. They started off with the intention of building one out of a couple of movements they already had.

"I came up several times and talked to Mike Bolles, the design engineer, and he asked, 'If we did make a production camera, what would you like to see on it?' We made a list of things they hadn't really planned on doing, like follow focus, crystal-sync, quiet operation, video tap, and so on. Over a period of time, they built a wooden model and I brought in Clyde Bryan, an assistant I've worked with a lot, and he gave them opinions of what an assistant would like to see on it and how he thought it could be made most workable, including aids to carrying it, a hook on it for tape measures, and follow focus. They hadn't initially thought of follow focus, because on the other cameras they generally just fix the focus and don't do a lot of follow-focus work. They asked, 'How about a manual follow focus?' The problem with the Nikon lenses is that it's so hard to see them, which gives the assistant trouble, so we asked, 'How about an electronic one?' They found a very convenient electronic system that is made in L.A. and it interfaces with Hayden follow focus and zoom movements. They built that into the camera and put the rings on the lenses. We modified the video tap to put on a color camera, so we could do our special matting work on that."

They also decided where the handles should go, how the camera should open, and what the length the eye-tubes should be. They put in eyepiece heaters and numerous other features designed for the convenience and speed of a regular production camera. "The technicians have done a remarkable job," Cundey enthused. "The motor was built by one of the engineers at Cinema Products. Magazines were modified to have built-in tension takeup motors, so there is no need for belts. The pellicle for the video camera can be changed so we get more or less light to the video camera as may be required. We can slide the ground glass in and out and put frames on it for optical line-ups so that it can be used as an effects camera. When they got it built it was a little noisier than we wanted, so I made drawings of blimps. A couple of the guys in the model shop made a foam model and it gradually progressed till we made a large crude model to test it. It worked, and they refined it.

"We were able to shoot with production sound film that ordinarily would have to be looped entirely because of the noise of conventional VistaVision cameras. It's built of foam, layered with fiberglass and it has multi-layers of sound dampening and absorbing materials, a coated front window, and cables that pass through all the electronic readouts and controls. The base is a special dovetail they built in that's isolated from the rest of the base. The camera and blimp arrived in London just a day or so before we began shooting, and we were even making some modifications there as we shot. It was indispensable to the show."

Cundey revealed that he already has used the new camera on another production which also required intricate compositing. "Recently, I worked on Big Business at Walt Disney Studio. We were doing optical splits of Bette Midler and Lily Tomlin who were playing two pairs of twins who talk to themselves. Our first thought was to use the VistaFlex so we could record in it. It worked perfectly. What it means is that someone could now shoot a large-negative show which will yield theatrical prints of incredible quality."

Cundey earned Academy Award, BSC Award and BAFTA nominations for his work in this film, among other honors.

In this interview conducted at the ASC Clubhouse in 2011, he discusses his collaboration with the Roger Rabbit animation team, and how this experience would translate into the digital age while shooting Jurassic Park:

The cinematographer's subsequent feature projects included Death Becomes Her, The Flintstones, Casper, Apollo 13 and Looney Toons: Back in Action — many of which included equally complex combinations of visual effects and animation.

He more recently completed episodes of the Star Wars series The Book of Boba Fett.

In 2014, Cundey was presented with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award.

Of note, the VistaFlex camera was sold in a bankruptcy auction after ILM spinoff company Kerner Optical went Chapter 11 in 2011.