Don’t Panic, It’s Organic: A Swamp Thing Discovery Saga

The cinematographer details his experience while shooting this fantastical series based on the long-running DC Comics title — combining the Arri Alexa LF with Panavision T Series anamorphics for a distinctive look.

The cinematographer details his experience while shooting this fantastical series based on the long-running DC Comics title — combining the Arri Alexa LF with Panavision T Series anamorphics for a distinctive look.

By Fernando Argüelles, ASC, AEC

Images courtesy of the author and DC Universe.

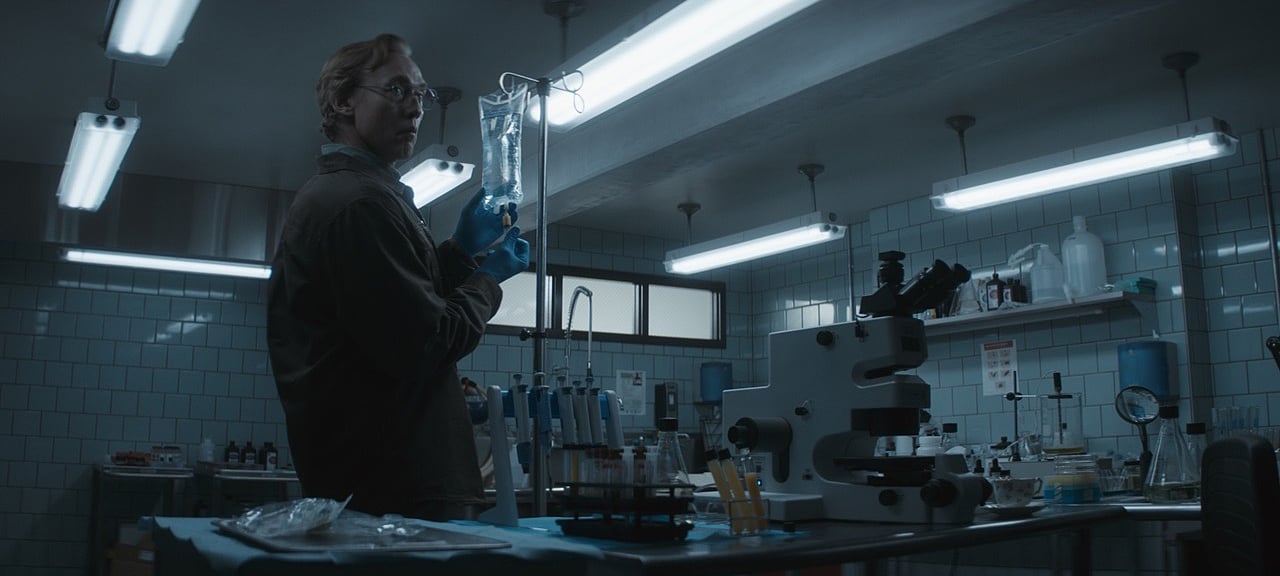

Swamp Thing is a DC Entertainment/Warner Bros. Digital Networks TV series that streams on DC Universe. Based on characters created by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson, and on the Alan Moore-written comic-book series Saga of the Swamp Thing, the story follows Dr. Abby Arcane (played by Crystal Reed), who returns to her hometown in Marais, La., to investigate a deadly virus. Her path leads her to Alec Holland (Andy Bean), a research scientist who disappeared after discovering toxic dumping in the local swamp waters.

When executive producer and showrunner Mark Verheiden offered me the show, I knew little about this superhero aside from the 1982 movie directed by Wes Craven. I was aware that Swamp Thing is an atypical fantasy character: He does not fly, shoot light beams, or possess any over-the-top superpowers. He is earthy, lives in a swamp, is surrounded by trees and water, and is driven by ecological concerns.

This endeavor really appealed to me, as I have always had a certain fascination with movies about jungles, forests and swamps. I love I Walked With a Zombie, directed by Jacques Tourneur and released in 1943; the excellent cinematography by J. Roy Hunt, ASC features deep shadows and high-contrast photography. With Swamp Thing, I saw the possibility of doing a series set in modern times with visual aesthetics that could be a bit old-fashioned. It promised to be both an adventure and a great creative opportunity.

Director Len Wiseman and I first sat down to discuss his vision for the show in Wilmington, N.C. After that meeting, I realized that even with almost four weeks of prep — a luxury for a TV show! — our goals would not be easily attained. The logistics, stage work, locations and schedule were all of a very large scale for a series. Nevertheless, I was inspired to be working with such a seasoned director.

Executive producer James Wan and the production team at Atomic Monster, along with Mark Verheiden and co-executive producer Deran Sarafian, were adamant about staying away from talking heads. They wanted to take an organic approach by keeping VFX to a minimum and allowing the artistry of lighting and production design to help create the world for Swamp Thing. This concept even carried over to our action scenes, wherein physical stunts helped us achieve realism without over-charged effects. In fact, most of our VFX work was used for tree and root transformations.

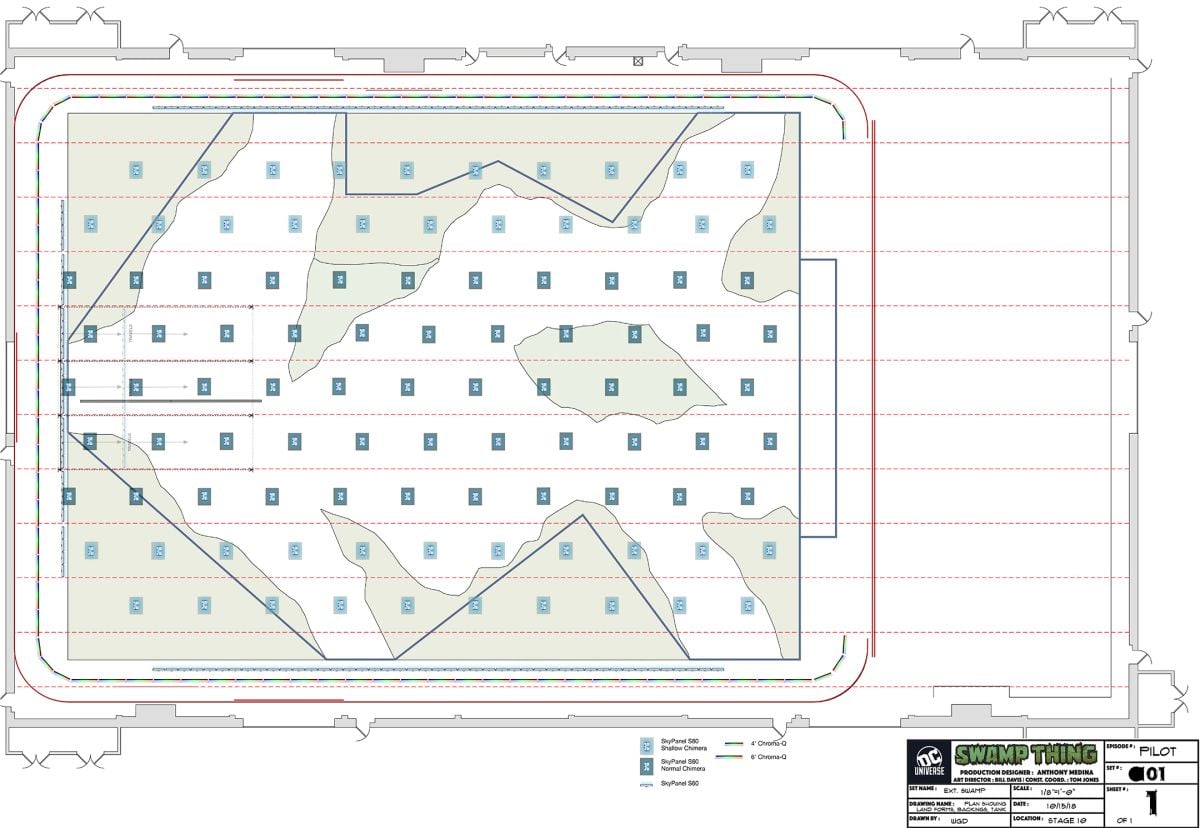

The series was shot entirely in Wilmington and the surrounding area. EUE/Screen Gems Studios provided our main stages, with Stage 10 housing our big swamp, which spanned approximately 160'x120'. The late production designer Charles William Breen created this incredible set, where most of the scenes with Swamp Thing occurred. The scripts called for the arrival and departure of boats, foot chases, and other action. Some scenes required actors and crew to be submerged in the water, so the “swamp” had to be kept clean; a filtration system under 24-hour surveillance was therefore put into place, and we also had a marine crew in charge of moving the boats, ensuring the safety of our cast and crew.

Stylistically, the show had to portray darkness and heavy atmosphere — i.e., smoke — with hues in bluish-green. I teamed up with gaffer Tommy Ray Sullivan, a legend in Wilmington and on the East Coast, and together we experimented with different color combinations. A total of 219 Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs were rigged to light the swamp from every side. Every LED light was controlled with a wireless DMX control unit called DimPad that was built and customized by dimmer-board operator Tommy Ray Sullivan Jr. After adding Chimeras with Magic Cloth to the SkyPanels, we could shoot from virtually any angle, using any selection of color and intensity. This was extremely useful for covering large areas when using wide-angle lenses.

Aesthetically, I like the SkyPanels’ light texture and medium-soft quality; they help me to create an overall soft backlight, and they wrap beautifully around the actors’ faces. Conversely, I don’t like night scenes looking bright and overlit unless the story calls for that style, as in a bright urban environment; overlit exteriors flatten the image, losing the depth I strive for in nighttime lighting design. Fill light was therefore kept to a minimum, and often not used at all. The soft light and heavy atmosphere in combination with filtration — I used 1⁄8, 1⁄2 and 1 Tiffen Black Satin filters, which soften contrast and highlights, creating a bit of halation from direct sources such as flashlights — were adequate for the drama and suspense we aimed to achieve. I also used ND filters from ND .3 to ND 1.8; I do not like to use NDs above that range because there is a color shift unless they are internal filters.

The colors chosen for the swamp sets ranged from medium and dark browns to medium and dark greens, with the bottom of our “swamp” tank painted dark gray or even black in some places. All these darkly hued elements absorbed quite a bit of light, and the palette didn’t naturally allow for much color separation or color contrast. When we needed a more direct backlight to create a deeper view with greater separation, we would place four generators on the ground, one in each corner, with a combination of lights: SkyPanel S360s, Arri M18s and M40s, or 18K HMIs with their Fresnel lenses removed depending on the depth we wanted to achieve. Ultimately, we used these lights more than anticipated, since all of these combinations still allowed us to use cranes, dollies, Steadicam, or pans across the swamp with little to restrict the scope of our frames.

Our set backing was as big as the swamp. To light it, we used about 33 Chroma-Q Studio Force II 48 and 135 Studio Force II 72 LED fixtures. I prefer Rosco’s SoftDrop backings, as they seem more realistic, offer a subtle softness, and present fewer issues at close range. Unfortunately, we were working with a vinyl backing that was too glossy, and when we received it at the 11th hour, it was still wet, with wrinkles everywhere. Key grip Dascious Thomas had a crew working around the clock to stretch it as much as possible; they used heat and continuous tension to work out the wrinkles.

Another matter to remedy was light spill on the backing. Most of our swamp scenes were set at night, and any hint of light that hit the backdrop was reflected. By using large frames with duvetyn, those reflections were minimized. Coupling that approach with heavy atmosphere, foliage and trees helped us considerably when we were shooting close to the backing.

Beyond the main stage, we had three additional locations for swamps and woods. On Stage 4, a smaller swamp/lake was built for Dr. Holland’s lab, suspended on pillars above the water. For this set, we rigged 28 SkyPanel S60s, four SkyPanel S360s, four M18s and three 6K HMIs — all of which were on motorized trusses — as well as 132 Chroma-Q Color Force II 12 LEDs.

Greenfield Lake, about 20 minutes from the studio, served as our real swamp/lake. There, we had boats traveling long distances, and a real dock for landing and shooting. However, despite the great location, we still had lighting challenges. Due to the size of the lake and a very busy road on one side, we had to use a mix of the biggest condors available, including two 135' condors, two 120' condors and one 80' condor, with two 18K Fresnels in each basket.

Lastly, the forest behind our stages provided the location for our big action scenes. We used four or five condors for night exteriors, typically with two 18Ks in each. Production designer William Davis did an amazing job dressing the forest with fake trees, small water ponds and extra vegetation to make it more “swampy.” I admit I was unprepared for the seasonal changes. In autumn the trees were sparse, by February their leaves began to return, and by March we had to add a closer, smaller 60' lift with two S360s in the basket because so much of the light from our condors was being lost in and absorbed by the foliage.

Perhaps my biggest lighting challenge was Swamp Thing himself, portrayed superbly by Derek Mears. The green suit — designed by Fractured FX at a cost of more than a million dollars — incorporated several shades of green, with the face being a bit darker than the rest. I therefore had to be careful to light the face without overexposing the rest of the body.

Much of the time, Derek wore a pair of red contact lenses that made him more menacing, but after hours of shooting, his eyes would need a break, and the red eyes were achieved with VFX. In either case, because the eyes were deep in the mask, we had to apply a special lighting treatment. We used Astera AX1 PixelTubes, dialed green to blend with the suit and make Swamp Thing look like he was of the environment rather than placed into it. When he was framed against trees and greenery, Swamp Thing required special back- and side-lighting. At 6'5", it was difficult to shoot him from low angles without the risk of seeing the stage ceilings and any rigged lights; we resolved this by adding VFX set extensions.

Panavision provided our camera and lens package, with Arri’s Alexa LF as our camera of choice. Our sets lent themselves to the use of anamorphic lenses, and so we coupled the camera with Panavision’s T Series anamorphics — which in turn needed to be paired with expanders to accommodate the large sensor. The expanders resulted in a minimal loss of light as well as an extremely subtle and pleasant softness around the edges of the frame.

ASC associate member Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering, was fundamental in fine-tuning our optics to create Swamp Thing’s distinctive look. We also carried 37-85mm (T2.8) AWZ2.3 and 42-425mm (T4.5) ALZ10 zooms, and ultimately rounded out our package with some extra spherical and “specialty lenses”: 14.5mm, 17.5mm and 21mm Primo Close Focus primes; a 12mm spherical; 24mm and 45mm Slant Focus lenses; an 85mm large-format bellows; a 150mm Macro Panatar; and a flare portrait attachment.

Most of my career as a cinematographer was with film. When I was first introduced to the Alexa, I was impressed with the sensor’s image quality, “film look” and “forgiveness.” Swamp Thing was my first introduction to the Alexa LF, and I noticed improvements in both the tonal scale and dynamic range. The combination of the large sensor and anamorphic lenses created a cinematic depth of field. Moreover, the signal-to-noise ratio was excellent for our dark environments and extensive night work. I rated the camera, depending on day or night, between 3,800 and 4,200K, with an ASA between 800 and 1,600. Our specs were: Open Gate 4.5K (4448x3096), ProRes 4:4:4:4, 12 bit, 2x anamorphic squeeze (framing for 2.20:1).

All in all, Swamp Thing was a unique experience that required a tremendous effort from everyone involved. With any creative endeavor, unexpected obstacles always arise. Beyond our technical challenges, we were introduced to Hurricane Florence, which put us behind schedule on an already complicated preproduction. My thanks go to alternating DP Nathaniel Goodman, ASC; visual-effects supervisor David Beedon and the VFX team; Justin Raleigh from Fractured FX; and Paul Westerbeck, our very talented colorist from Picture Shop Post in Burbank.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to Charles William Breen, our original production designer, whose vision made our swamp set come to life as a character unto itself. Charles passed away during preproduction, but his legacy allowed my creativity to flourish.

Argüelles became a member of the ASC in 2018. You'll learn more about him on his personal site, here.