ICS 2016 – Part VI: Safety, Leadership and Opportunity

The International Cinematography Summit offered a unique opportunity for motion picture professionals to discuss and demonstrate ideas.

ICS 2016

For this unique four-day event, the American Society of Cinematographers invited peers from around the world to meet in Los Angeles, where they would discuss professional and technological issues and help define how cinematographers can maintain the quality and artistic integrity of the images they create.

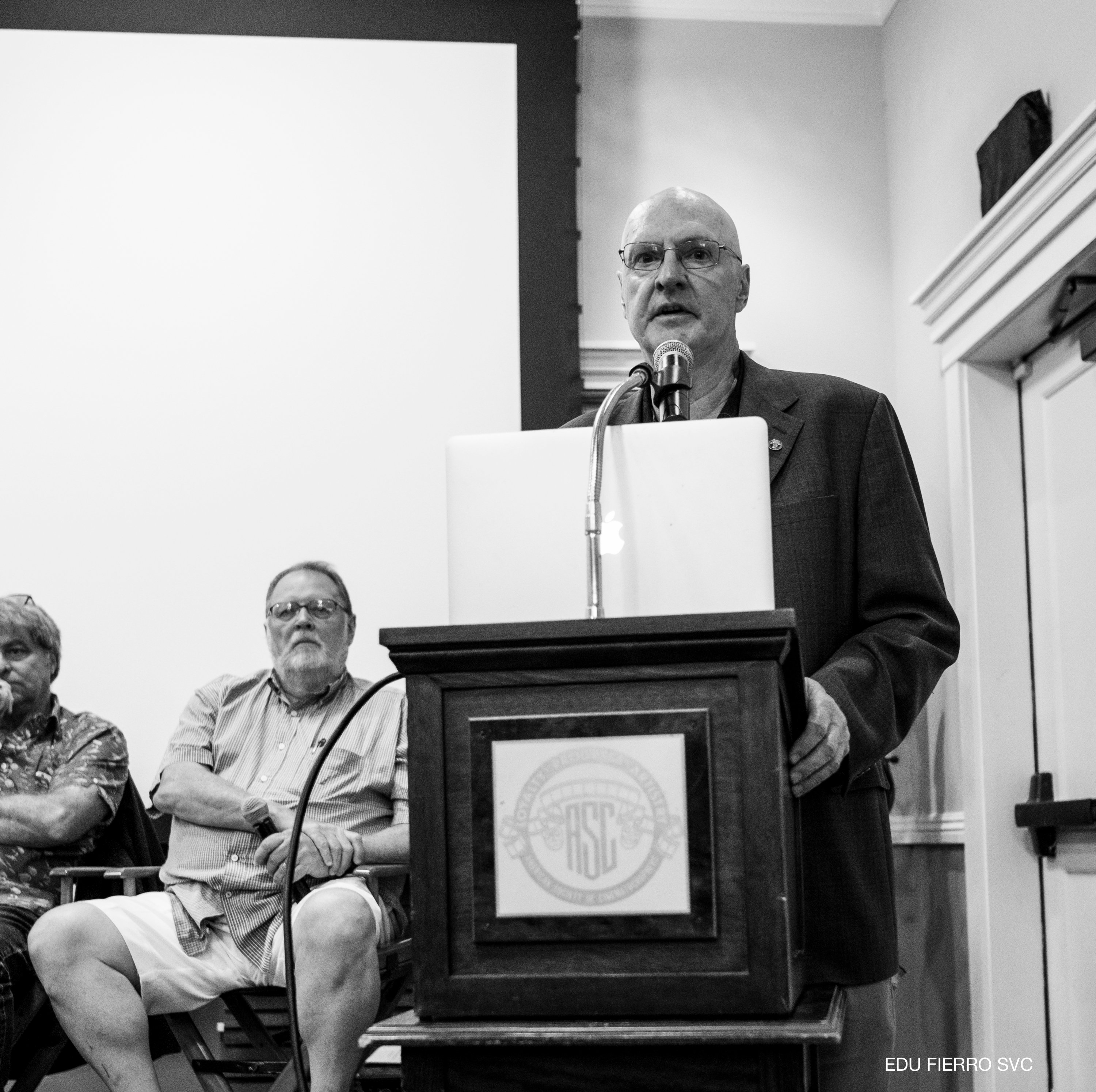

In this portion of the International Cinematography Summit (ICS), attending directors of photography from around the globe retreated to the ASC Clubhouse for a panel titled “The Role Your Society Plays in Your Workplace Environments.” The theme called for a broad range of topics to be discussed, including safety issues and opportunities for women, minorities and students. The open discussion was moderated by Ron Johanson, ACS and Richard Bluck NZCS.

Speaker Bill Bennett, ASC pointed out that safety issues are often overlooked because below-the-line crew are concerned about losing their jobs for speaking up, or not landing the next gig.

As an example, Bennett brought up the 2014 incident in Georgia, during which the production crew on the film Midnight Rider set up to shoot on a bridge where there was an active railroad line. Without the producers having proper permissions, permits or safety protocol in place, a speeding train tore through the location, resulting in camera assistant Sarah Jones being killed and several other people injured.

“And the reality was the location scout had asked permission to go up on the bridge and permission was denied two times," said Bennett. "And the location manager, who I happen to know, told the production this, and they said, ‘We’re going anyway.’ And the location scout made the best decision he ever made in his life: He said, ‘If you’re going to go up on the bridge, I’m not coming to work.’ So he stayed home in protest.”

As Bennett pointed out, the Midnight Rider incident very much brought to the fore much of the discussion about production safety here in the United States.

“Any person on the crew can stand up and say, ‘I don’t think this is safe,’” Bennett told the ICS assembly. “And if that person feels like they might be penalized, there’s actually a telephone number that they can call, where they can anonymously say there’s unsafe activity occurring and they don’t have to feel like their jobs are in jeopardy.”

Richard Bluck, president of the New Zealand Cinematographers Society, said one key role that cinematographers play in this dynamic is providing leadership for the crew. “In the end, your health and the health and safety of your colleagues relies to a considerable degree of you and your workers to think about,” said Bluck. “It’s worth a consideration that we as societies must look after the people we’re working with and look after ourselves.”

As one cinematographer in the room noted, it’s the first AD who usually takes on that monitor role in the U.S.

ICS attendee Michael Chambliss, a business representative for IATSE Local 600, said that the International Cinematographers Guild maintains an anonymous safety hotline that’s active 24/7, 365 days of the year. He also cited the non-profit Contract Services Administration Trust Fund, or CSATF.org, as a source for information on safety training.

As many in the room pointed out, the lack of safety can often result from the excessive hours put in by cinematographers and other crew members, resulting in fatigue and a lack of clear-headedness.

This issue of sleep deprivation and the danger it poses was explored by the Haskell Weller, ASC in his 2006 documentary Who Needs Sleep?, and is a continuing problem in productions around the world. As one Chinese ICS attendee noted, there are no unions in China to provide safeguards, and he was only granted two days off during one five-month shoot: “If we set up a union in China we might be quickly kicked out,” he said from the ASC Clubhouse floor, with the hope that some sort of global organization could one day step in with jurisdiction that extends to all countries.

One of the most compelling discussion subjects may have been saved for last, when the five

women cinematographers in the room — Natasha Braier, ADF; Stephanie Martin, ADF; Elen Lotman, ESC; Nina Kellgren, BSC and Claire Pijman, NCS — were given the opportunity to talk about their experience as minority figures of the various societies in which they are members.

“The ratio [of women to men] we see in this room is the norm,” said Kellgren of the U.K. “There’s a kind of a conscious bias that prevents women from progressing. And this has a lot to do with the number of women getting into the film industry and [wanting to shoot] at a certain level. But there seems to be a barrier towards working on any large-budget features, and women get discouraged and drop out.”

For Pijman, who hails from the Netherlands, it’s a matter of visibility: “For women starting out, they see this as a world in which they won’t be able to cope, and a lot of young female DPs just drop out. When they go to workshops they only see men. They never see workshops taught by women DPs. So, I think there’s a need to show that we can work together.”

Martin, who along with Braier is from Argentina, also cited perception as key. “I think the only way things are going to change is that we lead by example,” she said, “by letting other women see us working, but also with us having the opportunity.

"And Natasha and I were just talking about this. We have eight active members in Argentina who are women, out of 50 members, which is actually a pretty big number compared to others. I’ve always tried to avoid looking at it as being a female cinematographer because I do the same work that you guys do.”

Lotman, from Estonia, agreed that visibility is key, but another important issue is being comfortable with one’s identity. Then she talked about her experience in meeting Australian-born cinematographer Christopher Doyle, HKSC — best known for his work with Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai — 11 years ago at the Berlin Film Festival. She was invited by the celebrated cinematographer — whom she called “completely crazy” — to apprentice on a shoot in Thailand.

“This was for me a life-changing experience,” recalled Lotman, “because Chris, as you know, is

no typical cinematographer. And so I’d look at him for two months acting completely irrational on the set and still being one of the very finest cinematographers in the world. And I came to understand that the only thing about being the best in the world is being myself, and that goes for all of you, too. At that point, I stopped trying to be a middle-aged man and became what I am today.”