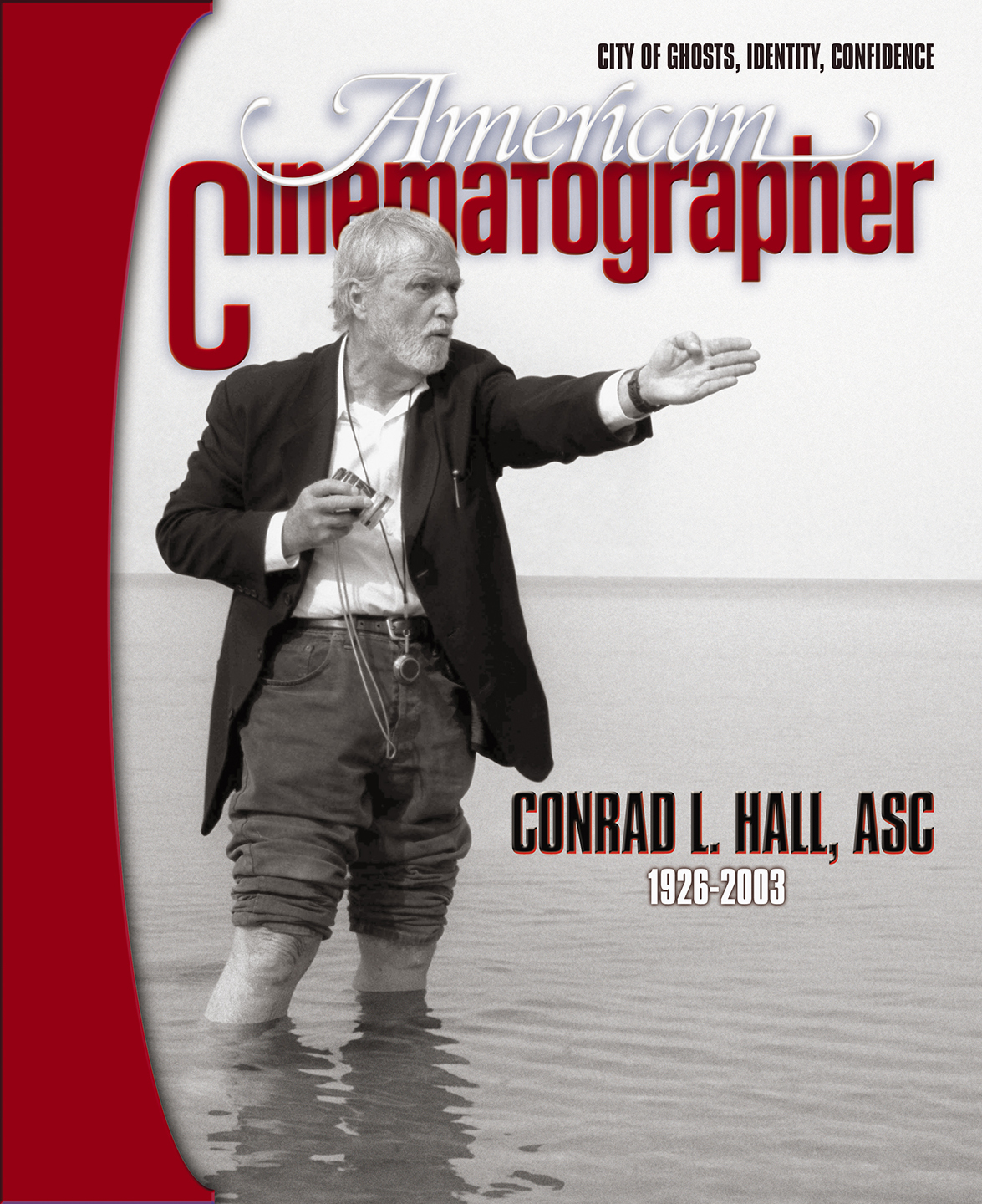

In Memoriam: Conrad L. Hall, ASC (1926-2003)

The esteemed three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer died on January 4, 2003 at the age of 76.

Esteemed three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer Conrad L. Hall, ASC — who helped changed the face of modern motion pictures with his camerawork in such films as The Professionals, In Cold Blood, Cool Hand Luke, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, American Beauty and Road to Perdition— died on January 4, 2003 at the age of 76.

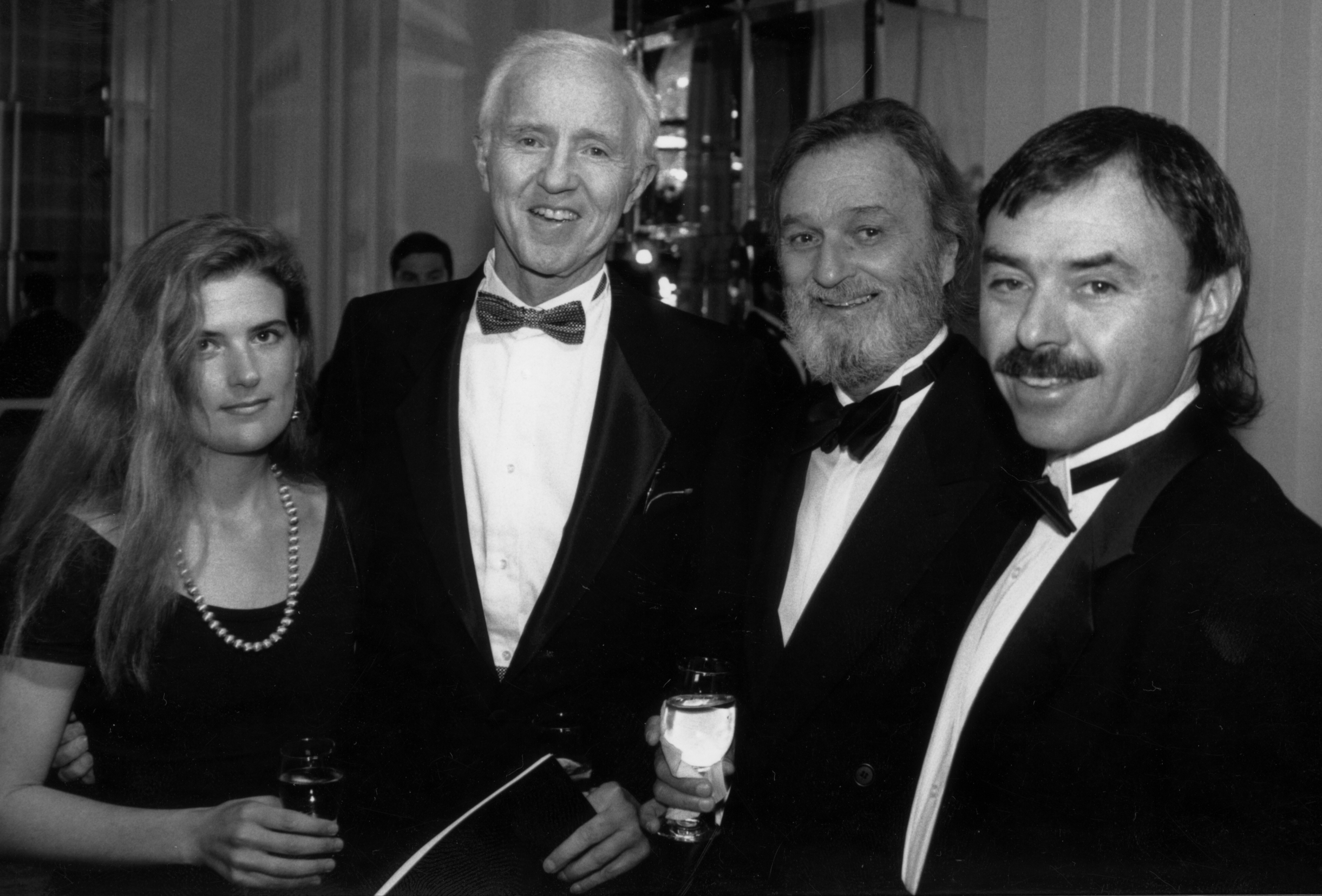

The following article was penned in 1995, when Hall received the Lifetime Achievement Award at Camerimage, the international festival of cinematography held annually in Poland. The piece originally appeared in the event’s program book, and is reprinted here with the permission of the festival’s organizers.

Artistry and the “Happy Accident”

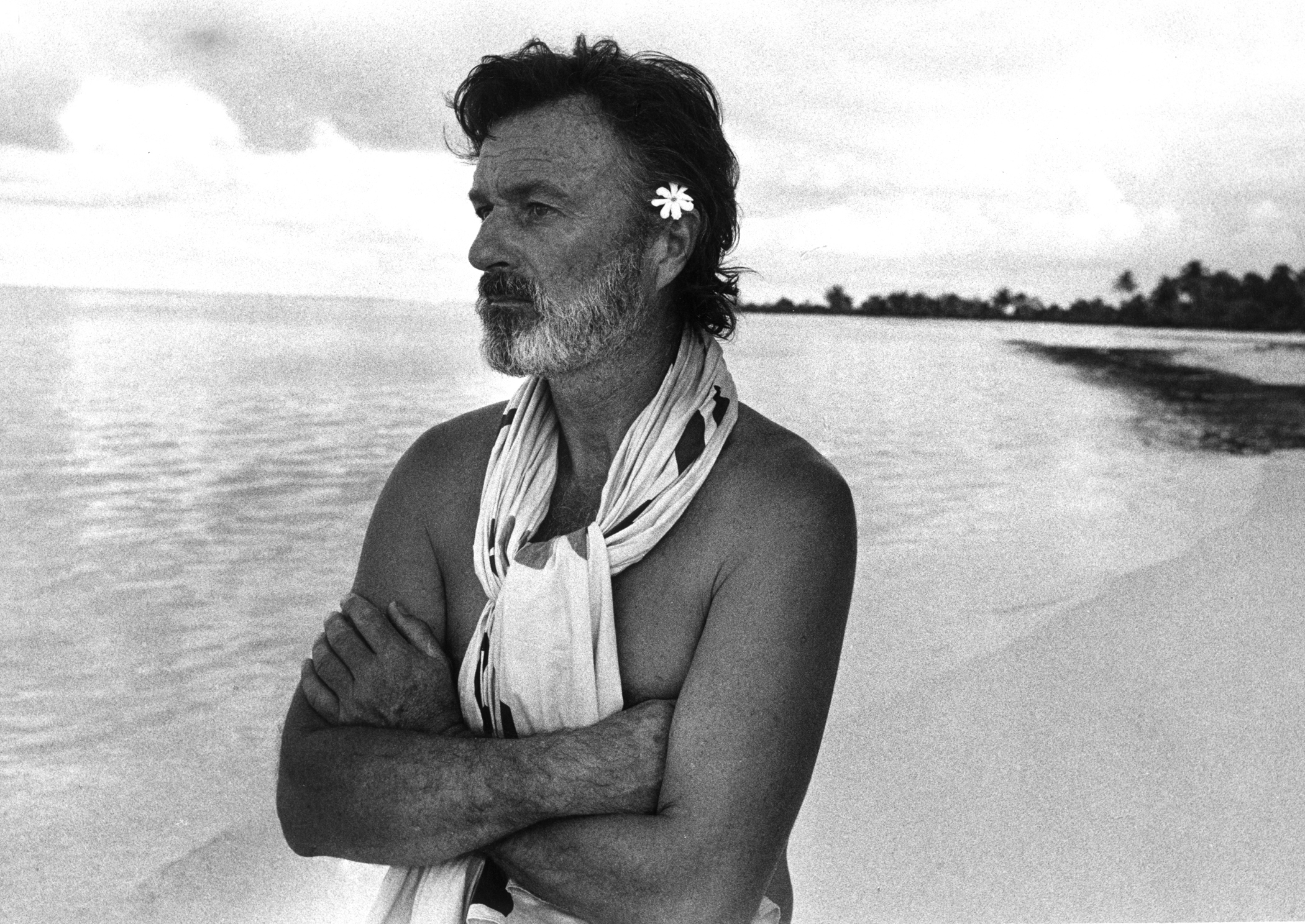

During his long and illustrious career, Conrad L. Hall, ASC captured a series of magical, indelible moments.

Cinematic brilliance can be defined in many ways. Some filmmakers, like Hitchcock or Kubrick, are obsessive planners who create meticulous blueprints in their minds. Others prefer more organic methods — cutting loose with the camera in an attempt to catch lightning in a bottle, whether it be an actor’s spontaneous gesture, a sudden reflection of the light, or the inexplicable poetry of a single moment in time.

Throughout his brilliant career behind the camera, Conrad Hall, ASC, had a keen eye for what he called “the happy accident, the magic moment.” Like a dowser seeking water, Hall used his camera as a divining rod, following his instincts toward an existential font of imagery. His willingness to take risks resulted in a rich cornucopia of cinematic triumphs, an aesthetic legacy that earned him the unflagging admiration of both his peers and film lovers the world over.

Hall’s greatest images are both timeless and sublime: a cascade of reflected raindrops that mimic tears on a killer’s dispassionate countenance (In Cold Blood); the mirror image of a chain gang, trapped in the sunglasses of an impassive prison guard (Cool Hand Luke); a faceless, horsebound posse in relentless pursuit of two mythical outlaws (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid); a solitary, backlit figure entering the cavernlike tavern that symbolizes his spiritual defeat (Fat City); the Bosch-like decimation of Hollywood Boulevard (The Day of the Locust).

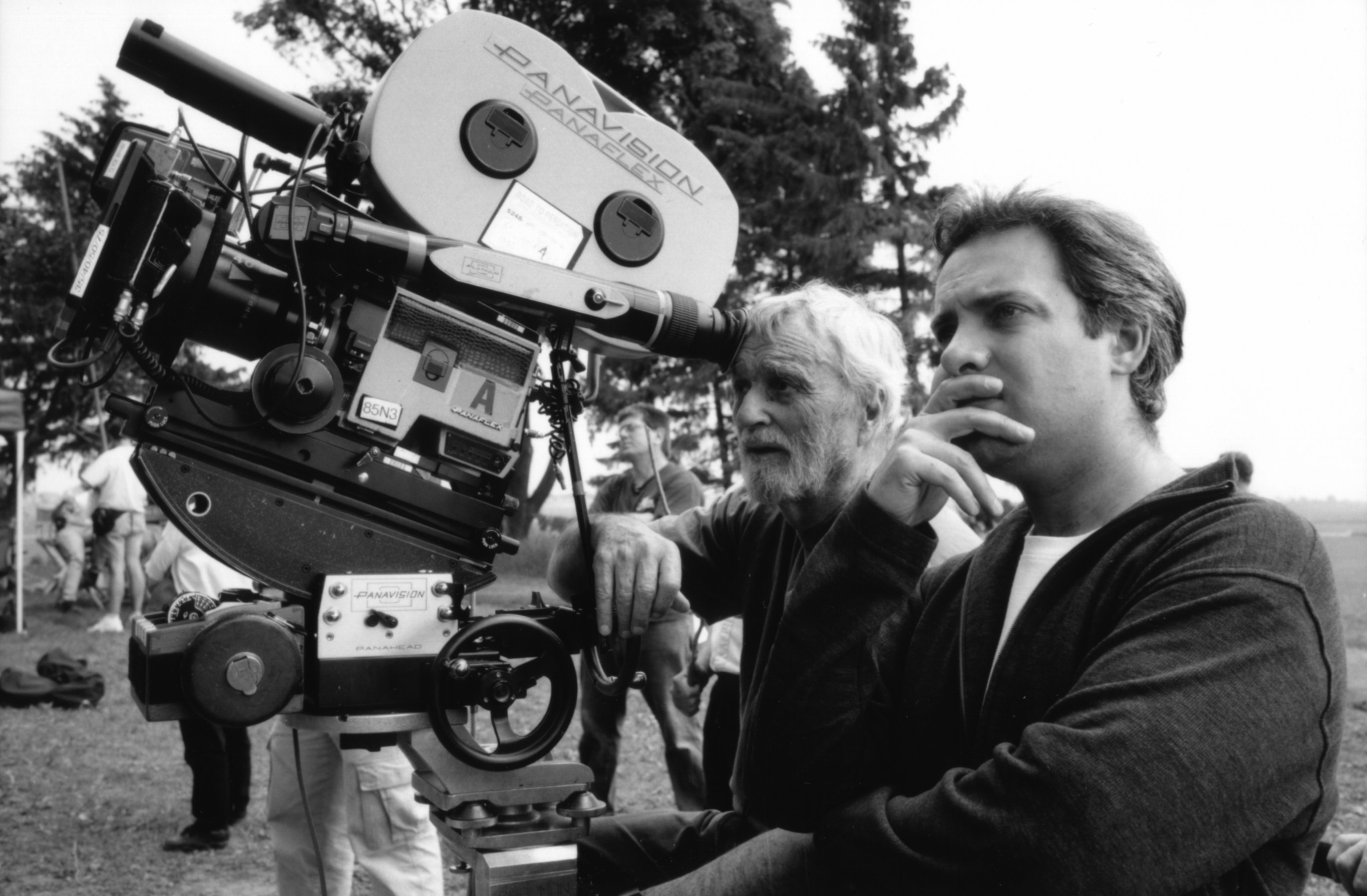

The list is endless, indicative of a mastery that seemed to grow stronger with each picture. After completing the beautifully crafted Searching for Bobby Fischer, a film that embodies both the wonders and terrors of childhood, Hall mused, “I’m looking for the accident, the joyous happenstance that comes with filmmaking, rather than going through some tortured manufacturing of the image.”

That philosophy guided Hall throughout his earliest days behind the camera. During his college years at the University of Southern California, he discovered an affinity for visual expression, but only after switching his major from journalism to cinema. “I found that learning how to tell a story with words was really not my cup of tea,” he said. “I really didn’t think about being a storyteller, but I noticed that the school had a cinema course, and that was very interesting to me for all the wrong reasons. You could go to school and study about movies, which was nonacademic and an easy way of getting through life. But the problem was, once I shot film and told a little story and saw it on a screen, I was deeply affected. I knew that this was something more than just movie stars, free trips and fame. There was a great power to be used in telling stories through pictures. The fact that the potential audience was so extensive was a very heady and profound concept for a young, idealistic person. I immediately took it to heart.”

His resolve was deepened by one of his instructors, Slavko Vorkapich, a Yugoslavian writer who had immigrated to Hollywood in 1922. Vorkapich, a master of visual montages, eschewed traditional modes of narrative storytelling in favor of pure visual expression, and he encouraged his students to tell their stories with pictures alone. Hall took his lessons to heart, and his career is a testament to the power of the Vorkapich philosophy. “In 1948 and ’49, we were allowed 100 feet of 16mm film per semester,” Hall remembered. “The rest of the time, our thoughts and ideas were realized on paper with stick figures and little frames — storyboards that we drew. We did a lot of theorizing, and Vorkapich got us to think visually, to tell a story solely with pictures. I work on that basis still. I take and extrapolate a scene visually so that if the soundtrack were to stop, there would still be a sense of what the story is about.”

Summing up Vorkapich’s impact upon his nascent artistry, Hall offered, “He had the spirit and soul of an artist. He taught us that filmmaking is a new visual language. He taught the principles, and said it was up to us to apply them. He gave us something few students get a chance to feel as early as we did — we were learning to be artists, using the filmic craft he taught us, communicating with artistic sensibilities, not commercial ones.”

After graduating in 1949, Hall joined two classmates, Marvin Weinstein and Jack Couffer, to form an independent production company, Canyon Films. While preparing to shoot their first feature, which all of them wanted to direct, they wrote job titles on scraps of paper and tossed them into a hat to determine who would be producer, director and cinematographer. Hall’s pick was cameraman. That stroke of fate began his path toward membership in the International Cinematographers Guild and became one of the defining moments of a career. Hall soon found himself operating for such esteemed ASC cinematographers as Ted McCord, Robert Surtees, and Ernest Haller. While all of these artists had an influence on his cinematic thinking, Hall singled out McCord as a particularly important mentor. “He wanted to give something to the story, to contribute a way of seeing it that was special and pertinent to the material. He also wanted to be original, and not reproduce something he’d seen in a painting or in somebody else’s work. And he was always frightened on whether or not he was succeeding. So from Ted I learned about going to the edge with your knowledge of cinema, and about trying to do something different or new. You should never work from a masterly sense, but from the sense of ‘Isthis going to work or not?’ I still think that way.”

Hall’s willingness to take artistic risks manifested itself early on during shooting of the low-budget road picture The Wild Seed (1965). This black-and-white film proves that Hall always had an inherent knack for conveying abstract ideas and subtle thematic concepts through inventive use of the camera. The film’s story concerns a young, adopted woman who travels across the U.S. after discovering that her real father is living in California. Along the way, she meets a young man who initially sees her as someone he can exploit. One day, camped by the road, the girl reads to her companion from a letter written by her birth father. Hall’s creative camerawork resulted in a sequence that remains among his personal favorites. “As the girl reads the letter, the boy sits on a rock, maybe six feet away,” Hall detailed. “I started to pan from her reading the letter across the emptiness to an extreme close-up of him listening. The look on his face showed how his feelings towards her were changing. The power of the scene results from the marriage of his performance to the movement of the camera. It was a powerful shot, and it worked beautifully for the story.”

On his next picture, the black-and-white wartime sea drama Morituri (1965), Hall discovered — in as nerve-wracking a way as possible — the blessings of the collaborative process. “While shooting for a complicated day-for-night scene, the wrong filter was accidentally used. I shot with that filter for three days, and when it went to the lab, word came back that there was nothing on the film!

“Terror and disappointment are the only words that apply to the way I felt,” he said. “Word of my impending unemployment reached my ears. But Bill Abbott, the wizard in charge of special effects at Fox Studios, noticed a very faint negative image. He made a high-contrast dupe on special film stock and saved the day. It was the best day-for-night footage I’ve ever shot, and that very ‘happy accident’ brought me my first Academy Award nomination. Thank you, Bill!

“That kind of experience really toughens you up,” he maintained. “Either you know for sure that you’re never going to be wrong or you get used to being frightened all the time. At this stage in my career, I’m pretty used to being frightened!”

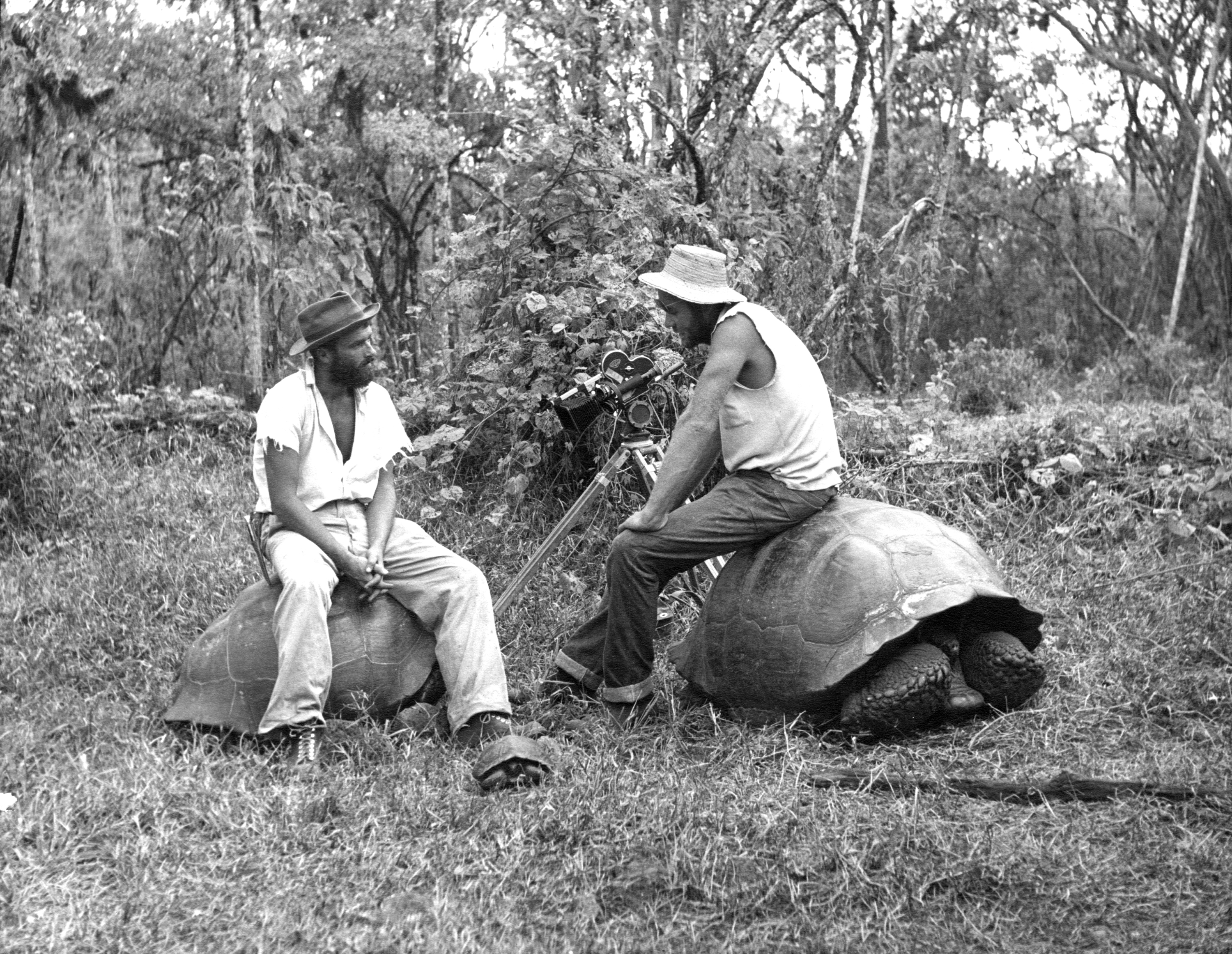

The Professionals (1966), shot in color, earned the cinematographer his second Academy Award nomination. It also marked his first collaboration with director Richard Brooks, with whom he also would shoot In Cold Blood and The Happy Ending. “Richard was an auteur,” Hall noted. “He’d had a lot of experience writing and directing, and he was a very strong visualist with firm ideas. He liked to have a very close working relationship with his cinematographer. You lived with him and ate with him, and you were always talking about the story and planning ahead. More likely than not, if you had an idea he’d thought of it already, so it became a matter of making his ideas work rather than coming up with your own. He was very certain about his ideas, very passionate. I loved working with him. We were friends.”

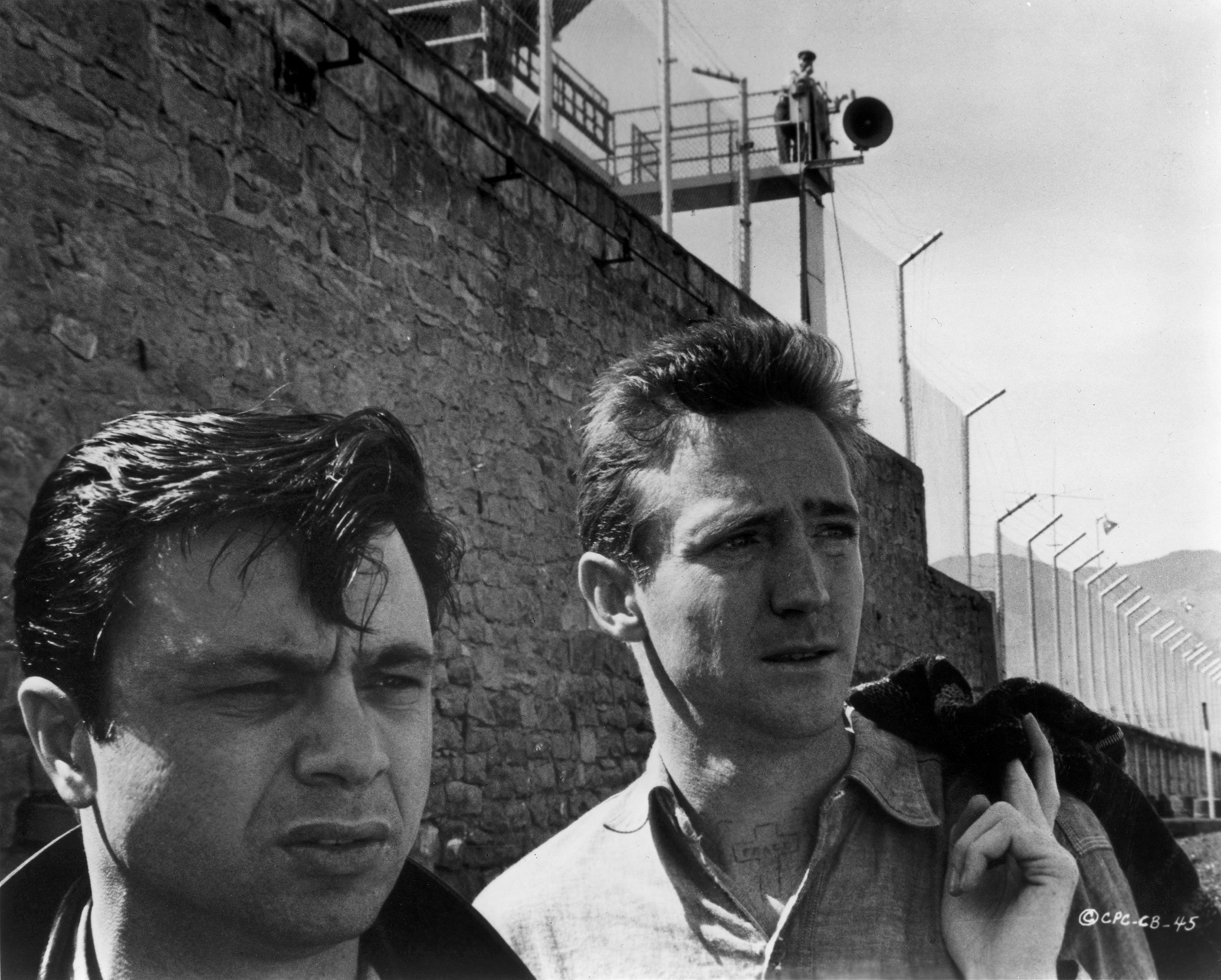

Hall’s next major success was Cool Hand Luke (1967), an anti-establishment allegory about a resilient rebel (Paul Newman) who is sentenced to a sweaty term on a repressive prison farm in the American South. It was on this project that Hall began experimenting with the art of imperfection. “In the pioneering days of cinematography, the idea was to strive for a kind of visual perfection, a beauty that came from an almost surreal perfection – skin that glowed, focus that enhanced the romantic senses, lighting that was always beauteous,” Hall said. “Then things began to change. I was part of both eras.”

Along with other pioneering cinematographers such as Haskell Wexler, ASC, Hall began breaking away from the beauteous imagery of the past to a grittier, more naturalistic sense of reality, in keeping with the evolving times. Hall used techniques that had previously been perceived as mistakes — an “inappropriate” move, or a flare in the camera lens — to dramatic effect. Indications of this daring strategy appear throughout Cool Hand Luke, particularly during scenes of the chain gang slaving under the blazing sun; Hall allowed the sun’s rays to ricochet off the inner lenses of his zoom, creating “zingers” of flare that underscored the misery of the midday heat.

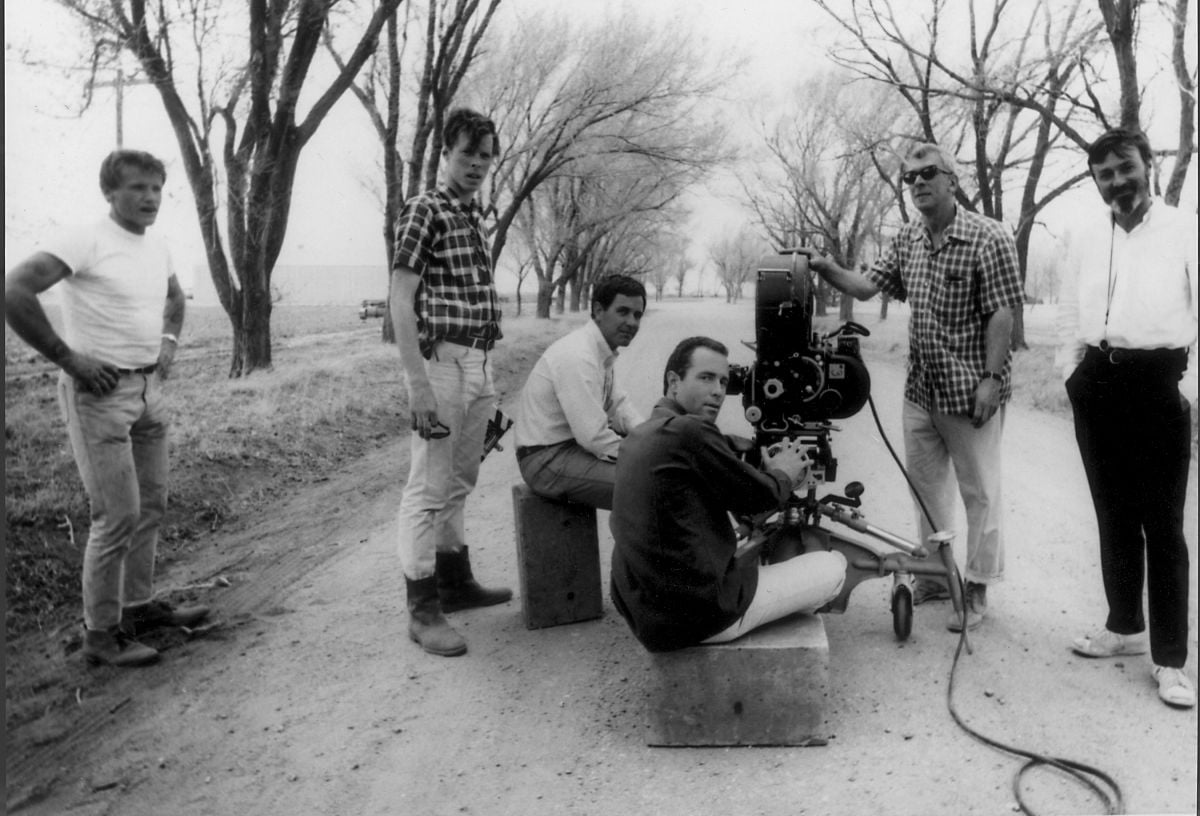

With his next picture, In Cold Blood (1967), Hall reteamed with his friend Richard Brooks. A triumph on every level, the film is a devastating dramatization of Truman Capote’s true-crime story, which details the slaughter of an upstanding Kansas family by a pair of unbalanced drifters. “We decided to shoot in black-and-white because we wanted to make it real; we were filming in the actual locations where the various incidents in the story had taken place, including the actual murder sites, and the use of black-and-white gave the film a heightened sense of truth without making things too lurid.”

Hall’s work on this film earned him his third Academy Award nomination and the undying admiration of cinematography buffs, who now view In Cold Blood as a nearly flawless achievement. The film offers a dramatic mixture of careful planning and on-the-spot inspiration.

Perhaps the most famous scene in the film presents a final speech by one of the killers (Robert Blake), who confides his feelings to a prison chaplain just minutes before he is executed on a rainy night. Among the many “happy accidents” Hall exploited during his career, this sequence stands alone in its brilliance. As the unemotional murderer reminisces to the chaplain about his unhappy relationship with his father, the drizzling rain outside the cell’s window is reflected onto his face, forming a river of symbolic tears.

“It really was raining the night the two killers were hung,” Hall recalled. “The warehouse where they were hung and Death Row were two locations in which we weren’t allowed to shoot, so we had to recreate them. I wound up lighting this scene of a man about to be hanged, talking to a chaplain as rain was being created outside the window. The light from the prison yard was creating a dim, moody ambiance, and the chaplain was reading from the Bible by the light of a little desk lamp. The outside light was creating the penetration, and we used a wind machine to create some movement in the rain. But the machine blew a mist on the windowpanes, and after a certain point the mist became so heavy that it started to trail down. While I was lighting the scene, I noticed that the light from outside was shining through the water sliding down the window pane and projecting a pattern resembling tears on the face of Robert Blake’s stand-in. I brought it to Richard’s attention. In the finished scene, the acting, cinematography, direction and writing all come together to create a very memorable moment.

“People think you’re a genius for planning something like that, when in reality you were just smart enough to notice it and exploit it,” Hall related with characteristic modesty.

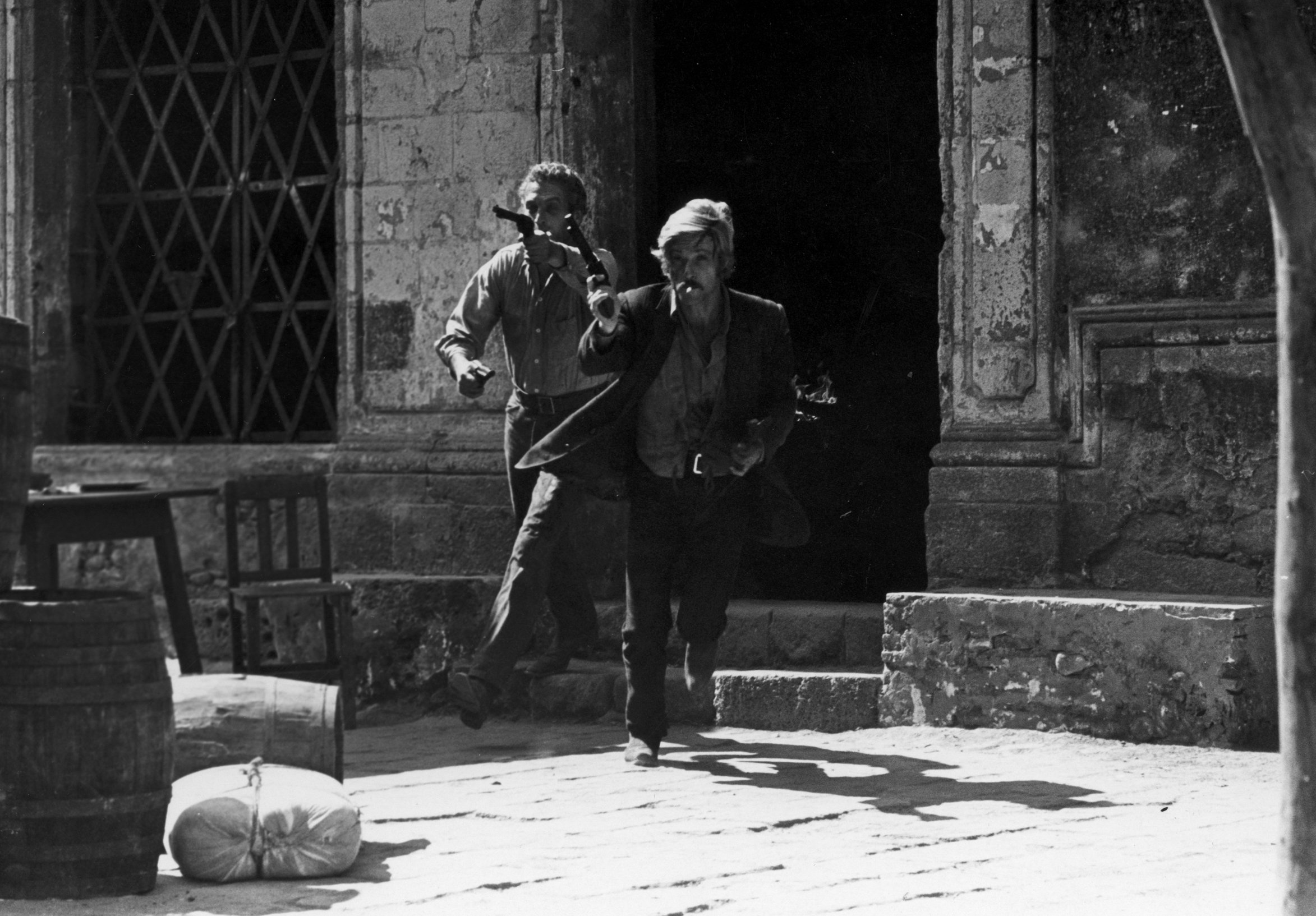

One of Hall’s next films was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). The cinematographer’s careful planning resulted in one of the great chase scenes in the history of Western films. “I love to work with symbolism, because it’s very strong visually,” he said. “Butch Cassidy is about the idea of people — in this case, bank robbers — being passed over by the advance of technological process. In helping George Roy Hill to visualize the chase scene, I was lucky to have the degree of freedom that he gave me. While shooting the posse, I used very long lenses, creating immediacy without recognition, keeping the reality symbolic. Banks were becoming invincible, and posses more formidable. Therefore, I wanted to keep the posse far away so you couldn’t see who they were; I didn’t want to humanize them and make them real people. It was an idea that was chasing Butch and Sundance. I usually work very organically and on the fly, but in that instance I had the chance to really sit down and plan things out fully.” Hall’s work on this film earned him an Academy Award.

After basking in Oscar’s spotlight, Hall was given the chance to work in tandem with one of his idols, legendary director John Huston. The two teamed up on Fat City (1972), the tale of a down-and-out boxer (Stacy Keach) who is reminded of his own past promise when he meets a young hopeful (Jeff Bridges). The boxer’s attempt to recapture former glories ends in the sad realization that it’s too late to turn back the clock. “That was a great experience for me, because when I was in film school John Huston used to come and talk to us. He was like a god; I mean, he had made Treasure of the Sierra Madre! It was unimaginable to me that I would someday be shooting for him.”

In an early meeting with Huston and production designer Richard Sylbert, Hall got a personal demonstration of the director’s creative intuition. “John asked us to tell him what we thought the film was about. I don’t remember what Dick or I said, but I do remember what John said. He told us, ‘I think this film is about how your life can run down the drain before you have a chance to put in the plug.’ That’s a brilliant summation of the concept, and it’s something I could hang my whole visual approach on. I always look for those kinds of guiding ideas when I’m shooting.

Huston sent Hall off with a camera to catch real-life, documentary-style examples of “life running down the drain” in the seamy skid row areas of Stockton, California. “I got a camper and covered the rear and side windows with black curtains,” Hall remembered. “I had quick-set mounts on tripods in each window and just moved my Arriflex from window to window depending on what I saw. At one point we stopped at a stop sign and saw a guy getting a haircut. So I quickly hauled the camera over to that window and zoomed right in — pick a stop, any stop! — and got a shot of this guy just sitting there, staring into space as time went by. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed this clock above him, so I just panned up to the clock and back down to this guy.

“When John, the crew and the actors sat down to look at the footage I’d compiled, you could have heard a pin drop. Some of it was devastating. It really gave you the sense of the harshness of these lives that we were recording, and it provided an all-too-real reference point for the actors.”

From the very first frame, Hall’s moody photography on Fat City sets the story’s tone of melancholia and spiritual exhaustion. In the much-admired opening shot, we see Keach’s character slowly,wearily brace himself for another day in the cramped, lonely confines of his small apartment. Hall lit the scene almost entirely with existing daylight. “The opening sequence was a perfect example of taking advantage of God-given light, just opening the lens and using what was there,” Hall said. “Stacy moves over to the dresser, and the light that’s coming in hits the wall and silhouettes him. I know how to use movie lights, but I can also see when the natural light is perfect.”

Despite the ideal meshing of the photographic style with the story, Fat City was snubbed by audiences, but Hall always rated the film among his personal favorites. The cool reception the film received led him to alter his approach on a subsequent project, The Day of the Locust (1975), a memorable adaptation of novelist Nathaniel West’s searing indictment of Hollywood venality in the 1930s. Mindful of the commercial failure of Fat City, Hall agreed with director John Schlesinger to opt for gauzy, golden tones instead of grit. “My vote was for color on that picture, because the story was similar to that of Fat City,” Hall said. “Locust deals with the frustration of ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful people who are surrounded by this golden wealth. As long as they’re close to it, they’re happy, but if they can’t stay close enough their frustration will just explode. The look we settled on was all about the characters’ hopes and dreams. The gauzy style of photography was meant to reflect the way these frustrated people saw themselves — in a romanticized light.”

The cinematography on The Day of the Locust was widely praised and earned Hall yet another Oscar nomination. Buoyed by their successful working relationship, Hall and Schlesinger collaborated again in 1976, on the harrowing thriller Marathon Man, which starred Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier. “I loved working with John,” Hall enthused. “He’s very collaborative; he has a very sure sense of where he wants the story to go, but he’s totally open in regard to how you get there.”

Marathon Man (1976) ended Hall’s string of 18 films made over 12 years; he would not shoot another feature for 11 years. Schlesinger himself noted a restlessness in the cinematographer, and attributed it to Hall’s lingering desire to direct. During his long hiatus, Hall formed a commercial production company with his friend Haskell Wexler, and directed and shot hundreds of commercials. He also took up screenwriting, working on both an original script and another based on the William Faulkner novel The Wild Palms, a project he had long dreamt of filming.

Hall finally returned to feature cinematography in 1987 on Black Widow, a lush film-noir effort. The end of his self-imposed sabbatical initiated a period of artistic rebirth, and in 1988 he accepted director Robert Towne’s invitation to shoot Tequila Sunrise, a romantic thriller that earned Hall both an Academy Award nomination and an ASC Award for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography. The film offered many moments for photography buffs to savor, but one in particular has earned Hall repeated kudos: a gorgeous twilight shot of a swing set in the park. The cinematographer was frequently asked how many nights he needed to get the shot just right; he revealed that he shot the sequence like a commercial, using a portable swing set that could be moved so that the setting sun was always in the ideal spot. “Contrast is what makes photography interesting,” he maintained, “and there is more than one way to create it. I used all of those techniques on Tequila Sunrise.”

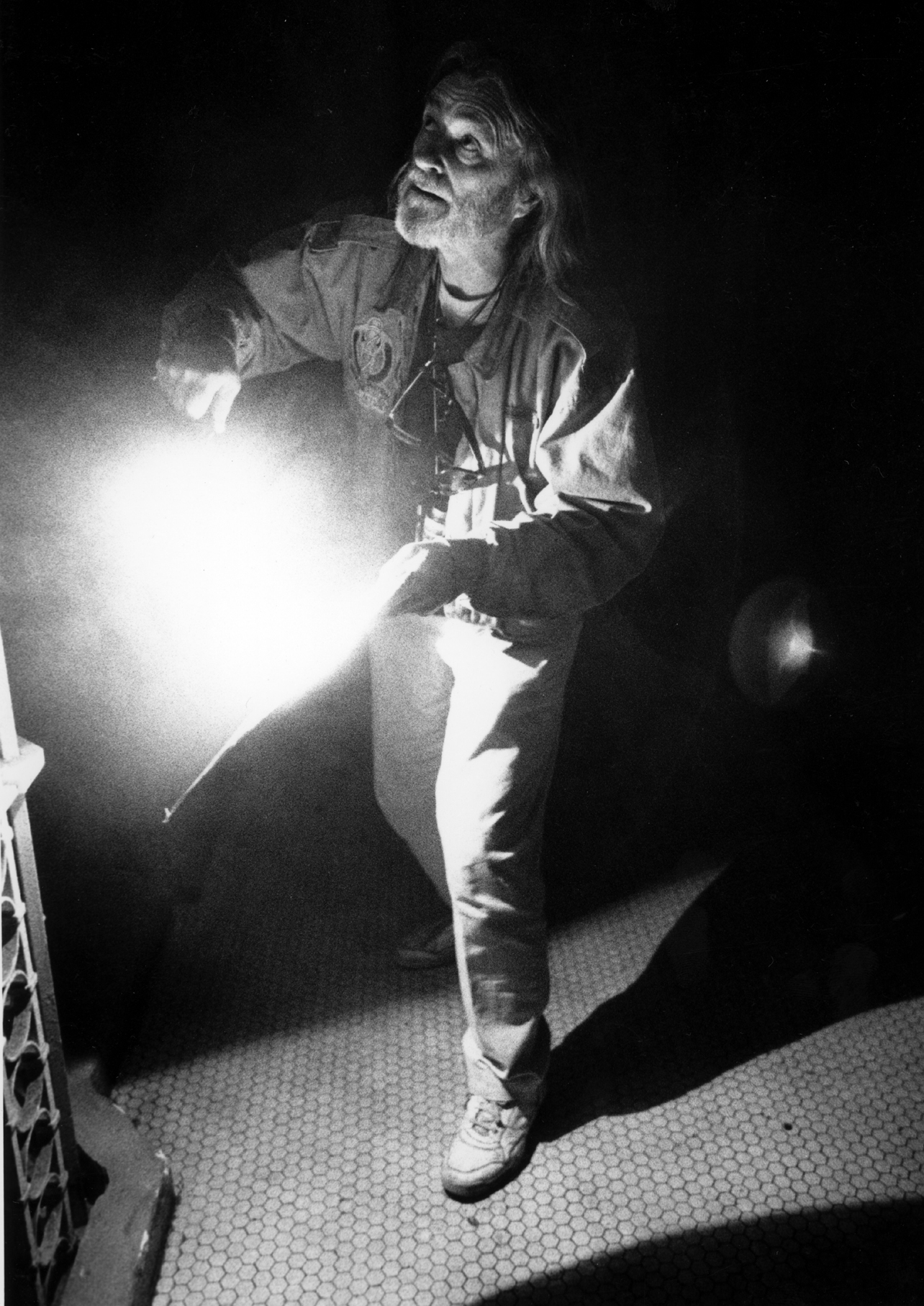

After the triumph of Tequila, Hall lent his talents to the films Class Action (1991) and Jennifer Eight (1992). He reserved a special affection for the latter film, an unconventional thriller directed by Bruce Robinson. Once again, he embraced the concept of darkness in the frame to create the tangible sense that the film’s heroine, a sensitive blind woman (Uma Thurman), was in true danger. At one point in the film, he strove to place viewers in the woman’s shoes by blinding them for a moment with a harsh blast of light. “I wanted the audience to have the same feeling that the two detectives [played by Andy Garcia and Lance Henriksen] have when they knock on her apartment door. Since Uma’s character is blind, she has no idea how her apartment is lit. She doesn’t pull blinds down at sunset to keep the sun out of her eyes — she has no conception of light in her mind. So when she opens the door, wham! The two men are blinded by the sun. We see nothing but blank film; she’s there, but we can’t see her. Then suddenly she steps in front of our blinding light and is revealed perfectly lit.”

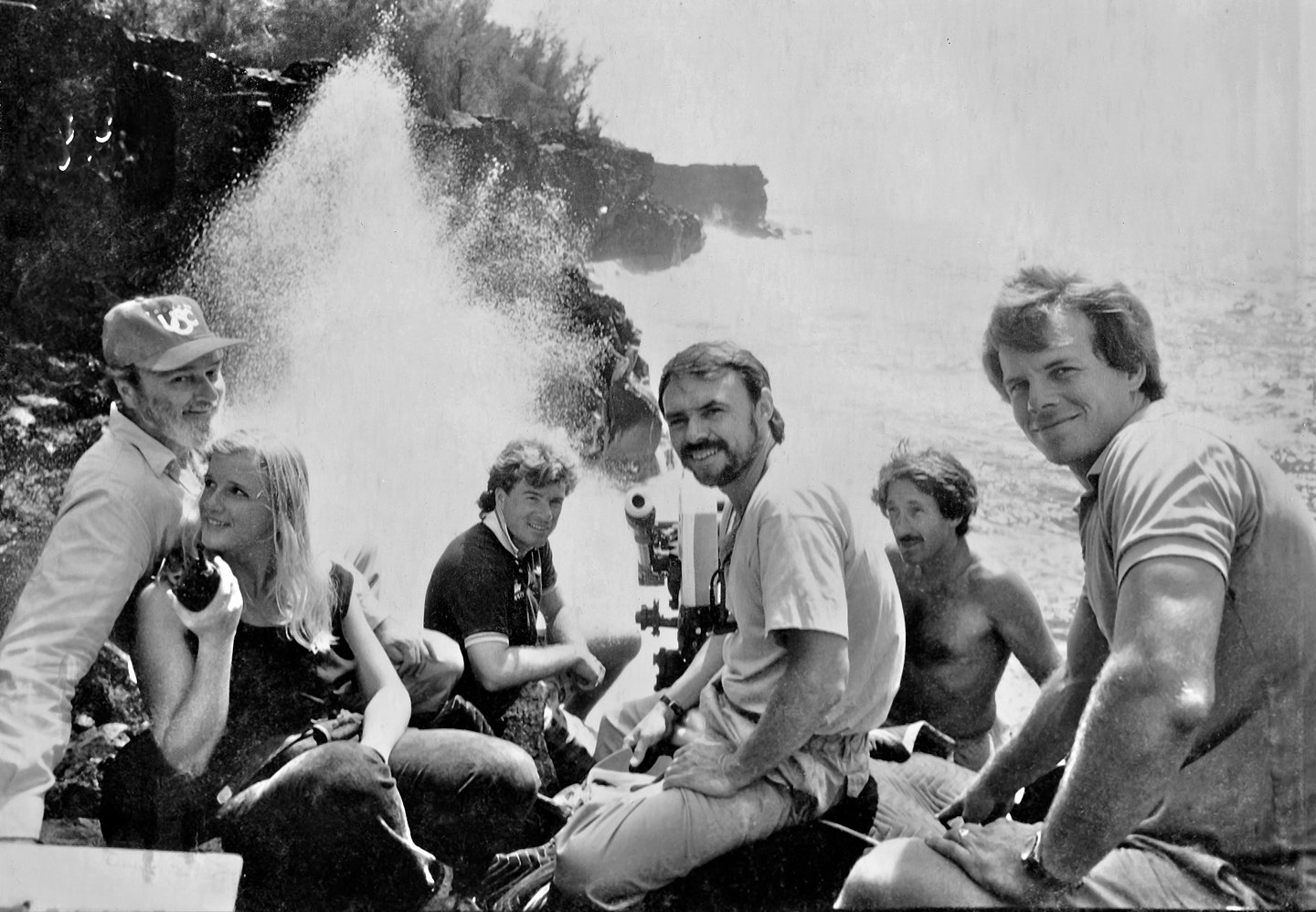

After finishing Jennifer Eight, Hall went on to shoot two films with distinctly different styles, both of which stand as outstanding examples of the master’s touch. With Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993), Hall and writer/director Steve Zaillian embraced the wonders of childhood as they told the touching tale of a young chess prodigy (Max Pomeranc) who confronts the pressures of his own excellence with the help of his father (Joe Mantegna). And with Love Affair, directed by Glenn Gordon Caron, Hall proved that he could recapture the kind of old-fashioned glamour favored by his early photographic mentors; in addition to gorgeous footage of Hall’s native Tahiti, the film boasts a romantic ambience that is rarely seen in modern films. The former film earned Hall his seventh Academy Award nomination, along with another ASC Achievement Award; the latter picture earned an ASC Award nomination.

Hall was particularly fond of Bobby Fischer, for which he created a style he dubbed “magic naturalism.” He explained, “Prior to this film, I had been moving towards naturalism on several other pictures — naturalism being, to me, ‘the way it is.’ The magic consisted of stylistic touches to heighten the atmosphere. A good example of this approach is a shot in which the father and son are coming down a hallway where there’s so much light they seem to be floating. I used 20Ks and just blew out the windows at the end of the hall. It’s those little things that give you that sense of ‘I’ve never seen this before,’ and that’s the essence of what magic is. Throughout Bobby Fischer, I used light in both exorbitant and understated ways. I’d occasionally use so much light that it would blow things out, but other scenes are so dark that you’re almost struggling to see. Of course, such an approach has to be integrated so it doesn’t distract from the story.”

In summing up the rich arc of his career, Hall suggested that cinematography, like every other art form, can only be satisfying if the practitioner is open to exploration in the purest sense of the word. Alluding to the Zen-like sense of fulfillment he felt while shooting Bobby Fischer, he asserted, “Filmmaking is about finding things out, it’s about examining, it’s about discovering. You should approach your work in the same way that a child discovers new aspects of the world. I draw inspiration from absolutely everything around me, and what I observe from life. When you get to be a visual storyteller, you learn to watch how people behave and to see things — to study the light, to watch a field as you’re driving by it in a car. It’s like making movies 24 hours a day.”

Following accepting his honor at Camerimage, Hall shot films including Without Limits, A Civil Action (earning another Oscar nomination) and American Beauty, for which he won his second Oscar. His final film was Road to Perdition, for which he was posthumously awarded this third Academy Award in a career that spanned five decades.

He is survived by three children — Conrad W. Hall, Kate Hall-Feist and Naia Hall-West — and his wife Susan Kowarsh-Hall.

Hall would later be honored with special career-spanning coverage in the May 2003 edition of American Cinematographer.

This in-depth interview was conducted in 1992: