In Memoriam: Willy Kurant, ASC, AFC (1934-2021)

John Bailey, ASC remembers the camera poet of the French New Wave.

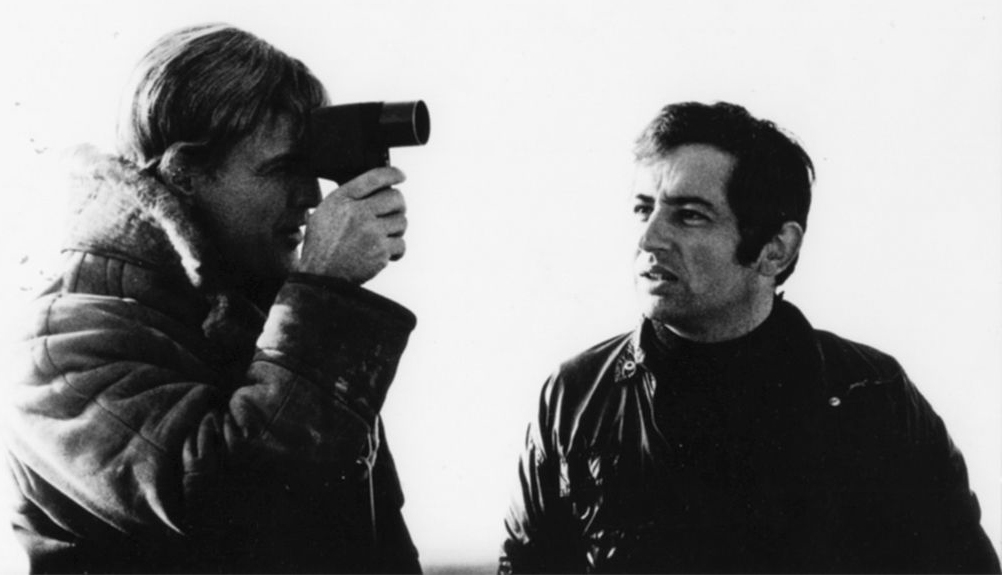

In the autumn of 1968, when I first met Belgian cinematographer Willy Kurant, he was 34 years old, living in Paris and approaching the apex of his French career. Along with Indochina War veteran Raoul Coutard, chain-smoking iconoclast Jean Boffety and genteel Catalan Néstor Almendros, Willy was one of the go-to cinematographers for French New Wave filmmakers; he had photographed several dozen documentary short films in the Congo, Turkey and India for directors such as Maurice Pialat, and feature-length films for Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, Chris Marker, Jerzy Skolimowski and Alain Robbe-Grillet.

When I met Willy that September at the Café de Flore in Saint Germain des Prés, he was still emotionally decompressing from shooting Hubert Cornfield’s neo-noir The Night of the Following Day, an American film set in France whose stars, bad-boy actors Marlon Brando and Richard Boone, were both wannabe directors of the project. As if that weren’t enough outsize personas to contend with, Willy had also recently wrapped the Orson Welles film The Immortal Story, starring the queen of the New Wave, Jeanne Moreau.

A dropout of the USC Cinema graduate program and a Peace Corps trainee recently “deselected” for my political views, I had come to Paris to visit my girlfriend and future wife, Carol Littleton, who was studying at the Sorbonne on a Fulbright grant. Already an acolyte of cutting-edge French movies (courtesy of Max Laemmle’s cinematic temple in Los Feliz), I was eager to breathe the intoxicating air of French cinema in situ. Willy asked me to meet him at the Café de Flore, a place that I soon discovered was sacrosanct to him.

An iconic venue that hosted the literary and cultural elite of 20th-century French arts, the Café de Flore is still a must-see for cultural pilgrims. Thanks to the famous montage of sidewalk passersby in Louis Malle’s The Fire Within (1963), starring Maurice Ronet, I could recall every exterior table at the café, and, after arriving early for my meeting with Willy, I sat at the same table Ronet had occupied. Like his character, Alain Leroy, I, too, was fully engaged in introspection when a delicate-featured man walked up and introduced himself as “Willy.” He immediately rescued both of us from my barely passable Peace Corps French with his perfect English, and he exhibited no trace of Gallic reserve or disdain. Initially, I attributed his openness to his recent experiences with unbridled American moviemakers, but as he spoke of his life and work, I realized his sensitivity was bred in the bone — the DNA of a life full of challenges.

Willy’s father, a Polish Jew named Jankiel Icek Kurant, took refuge in Belgium in the early 1930s as anti-Semitism raged through central Europe. He brought a daughter, Felicia, with him and settled in Liège. He remarried, to Tema Feuer, and on Feb. 15, 1934, Willy was born.

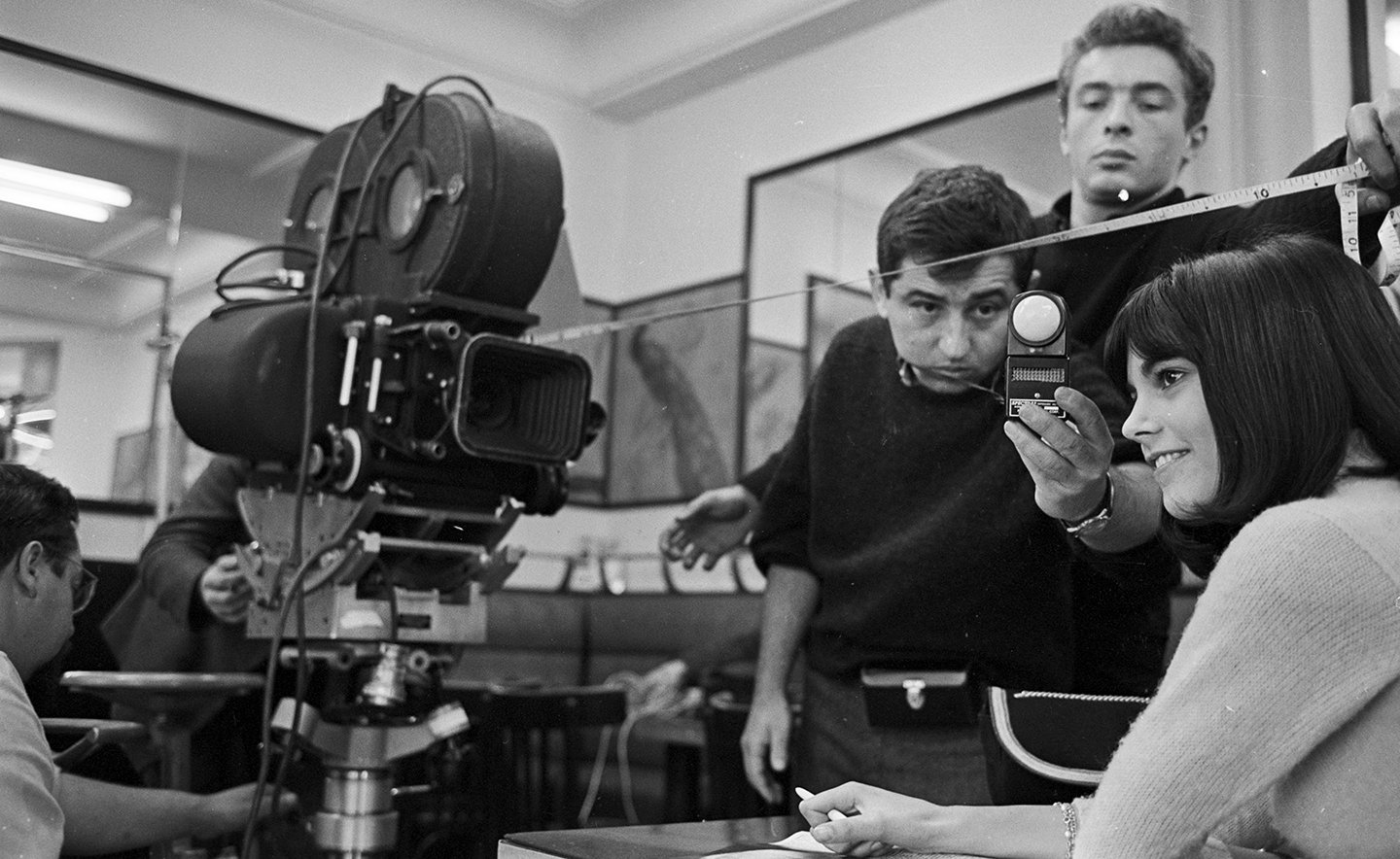

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded Belgium, and 18 days later, Belgium surrendered. Jankiel put his family on notice that, as Jews, they might be taken away; inevitably, a neighbor denounced them. It could have been a scene from a movie: One day, as Felicia bicycled home from school with Willy in tow, she saw Gestapo in front of their home. Following the instructions her father had given her, she kept pedaling. She and Willy never saw their parents again. Around that time, Willy contracted polio, which left him with a compromised right arm. (Nevertheless, he became one of the best handheld cameramen of his time, making many documentaries before his first two features, Varda’s Les Créatures and Godard’s Masculin Féminin.)

Avoiding German patrols, Felicia and Willy were able to find shelter with a Catholic communist family in the Ardennes. Felicia, much older than Willy, left to join the Resistance. In 1942, Willy continued his schooling under a false name in the village of Bison near Verviers, not far from Liège. Willy became a newspaper boy, distributing copies of the Red Flag. (The communist elements of his background haunted him for years as he struggled to maintain a career in America, even after Carol and I sponsored him for U.S. citizenship. Every time he passed through U.S. Customs, he was unjustly flagged as a “subversive.”)

When the war ended in 1945, Willy, not yet a teenager, continued his education in an orphanage in Boitsfort. There, a photography teacher (and Auschwitz survivor) found an internship for him in a motion-picture laboratory. This sparked Willy’s life-long study of the creative possibilities of photochemical alchemy. Many years later, I saw his expertise in controlled on-set exposure, laboratory development and printing firsthand when he photographed a film I directed, China Moon.

Willy was eventually professionally reunited with Pialat, the idiosyncratic director with whom he collaborated early in his career, and in 1987, Willy was honored with a César nomination for Pialat’s Sous le soleil de Satan, which also won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

On June 2, 2009, Willy’s beloved Cinémathèque Française honored him with a tribute — truly a dream realized.

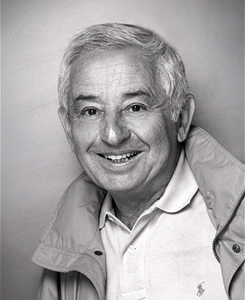

Willy died in Paris on International Workers Day, May 1, at the age of 87. Happily, his own account of his remarkable life survives him; while he was still in good health, he sat with my AC colleague Benjamin Bergery for an interview for the Academy Oral History Project. (The interview can be found at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library.)

Willy is survived by his wife, Hélène Robin, a gifted costumer who worked with New Wave icons as well as Serge Gainsbourg, another frequent collaborator of Willy’s. He was predeceased by his sister, Felicia, two years ago.

When I first sat with Willy at the Café de Flore in September 1968, not yet focused on how I could begin a career in the movies, I sensed I was speaking with a man whose singular devotion to his art would be a beacon for me. Neither of us could know then the paths our lives would take, or that we would collaborate more than 20 years later on a noir feature in central Florida. He may be gone, but the lambent light radiated by his work remains bright. We, film students all, have been enriched by this gentle man’s poetic vision.

Kurant was recommended for ASC membership by John Bailey, Allen Daviau and Steven Poster.

“Mr. Kurant has been a vociferous spokesman for the causes of cinematographers from all countries,” Poster wrote in his letter of Dec. 25, 1995, to the ASC Membership Committee. “I believe he will be an important and welcome addition to the ASC.”

Bailey noted in his letter of Dec. 27, 1995: “Of the several people whom I have had the honor to sponsor [for ASC membership], Willy is the person I most know and admire. He has been a longtime friend and mentor to me. I’m convinced that he will be an asset to us as an active member both in terms of his professional acumen and his expansive personality.”

“It has been 20 years since I first met Willy Kurant,” Daviau wrote in a handwritten letter dated Feb. 13, 1996. “For an aspiring cinematographer to receive inspiration from one of the founding members of the French ‘New Wave’ was an event I will always remember … I am certain he remains an inspiration to many.”

Kurant’s ASC membership was approved and made official on May 14, 1996.