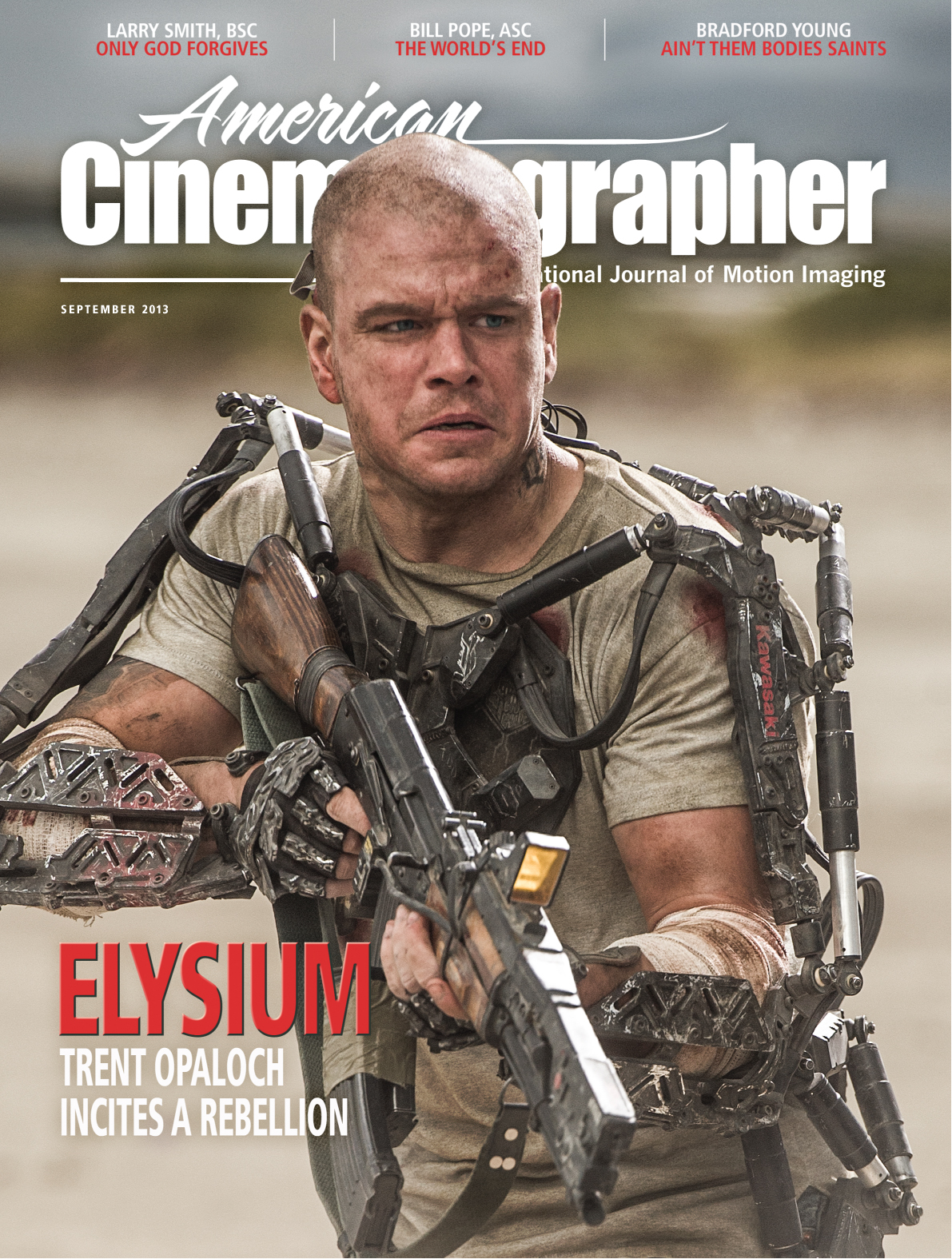

Bangkok Dangerous: Only God Forgives

Larry Smith, BSC reteams with director Nicolas Winding Refn on an atmospheric revenge thriller shot in Thailand.

Two years after winning Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival for Drive (AC Oct. ’11), Nicolas Winding Refn found himself buffeted by gales of controversy that greeted his next Cannes entry, the abstract and ultraviolent Only God Forgives. “It’s great to be the Sex Pistols of cinema,” Refn quips. “Polarization means you actually made a difference.”

A moody, existential drama that favors ambiance over conventional narrative and dialogue, God begins with the murder of a teenaged prostitute in one of Bangkok’s seedy redlight districts. Justice is swiftly meted out when police corner the killer, Billy (Tom Burke), and force the girl’s father to exact his own bloody revenge. The cop in charge, Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm), blames the incident squarely on the father and, in a pitiless show of state-sanctioned power, severs the man’s hand with a sword.

News of the killing soon reaches Billy’s brother, Julian (Ryan Gosling), a stoic drug smuggler who operates out of a kickboxing gym. Julian knows better than to confront Chang, who rules his territory with an ironclad code of vengeance, but his caution is mocked by his domineering mother, Crystal (Kristin Scott Thomas), whose emasculating tirades spur him to seek retribution. What follows is a mesmerizing game of cat-and-mouse, as Julian and Chang circle ever closer to a showdown.

Much of the movie’s dreamlike pull stems from its deliberate pacing, eerie imagery and dynamic musical score (by Cliff Martinez). “Minimal dialogue and the use of silence or music automatically forces the audience to pay more attention,” Refn contends. “I’ve made three films that have very little dialogue; the idea is that sound and music become much more active storytelling elements. If dialogue is logic, sound and music penetrate purely to the heart.”

Refn’s dedication of the film to avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky further reflects his intent, and he cites Richard Kern’s sadomasochistic short film The Evil Cameraman (1990) as another influence. “The Evil Cameraman is both terrifying and erotic, because it’s about a man tying up women in his apartment, and it’s set to a soundtrack of very strange music and sounds,” Refn observes. “It’s a fetish construction, very raw and real, but it’s also like a dream because what happens is so uncomfortable, bizarre and weird that it brings many subliminal images into the viewer’s mind.”

“In my view, it’s really a horror film with minimal dialogue.”

— Larry Smith, BSC

Refn says Only God Forgives intentionally reflects “the language of hypnotism,” a sensation he likens to Bangkok itself. “Everything in the movie is slowed down, and we were living that feeling while shooting in Bangkok. The heat is really intense there because the humidity is so high; it feels like you’re in some kind of strange underwater world. It’s very intoxicating and weird.”

Helping to capture that atmosphere was cinematographer Larry Smith, BSC, who began his collaboration with Refn on the feature Fear X (2003). Since then, the two have reteamed on the telefilm Miss Marple: Nemesis and the feature Bronson (AC Oct. ’09). Refn notes that Smith’s skill set was ideal for Only God Forgives, which involved budgetary constraints and locations that presented logistical challenges. “Larry is a very fast cameraman, and he’s also very good at using practicals — that’s one of his great strengths,” he attests. “Many of the locations in Bangkok had no windows, so we really could only work with practicals. Larry can also read a location very quickly. We couldn’t afford to alter very much at a lot of our locations, and others were so ideal we didn’t need to alter them at all. I traded most of the production-design budget for shooting days. Shooting at night usually means you’re working about 50 percent slower.

“This movie became an existential journey for everyone. Larry and I spent a lot of time discussing various interpretations of the story and the images, which have a lot of double meanings.”

— Nicolas Winding Refn

“By day, Bangkok is grand, pulsing, loud and insane — it’s like a mixture of New York, London and Los Angeles,” continues the director. “At night it’s an alternate universe where logic and the supernatural walk hand-in-hand. This movie became an existential journey for everyone. Larry and I spent a lot of time discussing various interpretations of the story and the images, which have a lot of double meanings. Those discussions can take hours, so to allow for that kind of back-and-forth, I needed to work with someone very fast and very precise.”

Smith confesses that Refn’s more abstruse concepts sometimes led to head-scratching. “Ryan Gosling and I had our own discussions about the story and what the movie was really about, and we did a lot of joking back-and-forth about what our understanding of it was! Nicolas plans some shots, but he’s always ready to try a new path if he sees something interesting happening on the set, so the film kept evolving as we went along. In my view, it’s really a horror film with minimal dialogue.”

Although Smith brought a few key crew members from the United Kingdom, most of the movie’s technicians were local hires. “We worked with three crews most of the time because we were using three cameras: two Arri Alexas [Plus] and Ryan’s Red Epic,” he says. “We met some of the guys during prep, but others I knew from commercials I’d shot elsewhere in Thailand. The camera crews there are fantastic. They’re very good technicians who work very hard and keep very quiet, and they love working on international projects.

“I hadn’t actually shot in Bangkok before, but I’d been there many times,” Smith continues. “Because the backdrop of the movie is the drug trade, I felt strongly that most of it should be shot at night. Bangkok really comes to life at night; it becomes a very rich visual backdrop with all the neon lights and color. We shot about 8½ weeks of nights. It was very hot and very demanding. Nicolas likes to shoot in strict continuity [story order], which meant we spent a lot of hours in traffic traveling to and from locations. This movie was really all about finding the right locations.”

Most of those locations were in the red-light districts of Nana Plaza, Soi Cowboy and Patpong. “Apart from the scenes in Julian’s boxing club, all of the wheeling and dealing takes place in locations that were actually sex clubs,” Smith reveals. “We went to all of these really seedy places — gay clubs, heterosexual clubs, bars. Most of them are actually very depressing, especially the hetero clubs. A lot of older guys travel to Bangkok from other countries to spend time with young Thai girls. The gay clubs are a bit more fun because they’re more theatrical.”

Smith’s economical approach to lighting was inspired partly by his budget (“I never had one,” he cracks), and partly by the fact that he could readily exploit the surreal existing lighting in Bangkok. “Truth be told, I didn’t need that much of a budget,” he maintains. “I just went to the local market and bought lots of Cool White and Warm White fluorescents right off the racks, including clip-on fluorescents we could run off a battery. I also picked up rolls of LED lights in different colors. For the nighttime street scenes, I was mostly using available light. When we found ourselves in a dark alleyway, I could just clip up a fluorescent somewhere. If we were in a really dark nightclub, I used a combination of LEDs and Dedos.

“I did add some extra light for the scene when Julian finally confronts Chang on the street. I think I used some Amber gel on a 1K to make it look like a streetlight; to make that less obvious, I just broke up the light through a tree or a bit of dingle. For bigger scenes, I added a couple of 1Ks or maybe a 2K, but that was really it. The only time I used any kind of film light was for Kristin Scott Thomas’ entrance scene at the hotel, where I used a couple of 18Ks through the windows, and for a couple of day scenes in Chang’s home.”

The movie begins with a striking tableau that introduces Julian’s boxing club as a main setting. The location was the Muay Thai Institute, a boxing venue located next to the Rangsit boxing stadium in Bangkok’s northeastern suburb. “The institute is a very famous place, but it’s also very rundown, very dirty and hot, hot, hot,” Smith details. “It went underwater during the floods two years ago, so it’s filled with mosquitoes. In addition to the main gym area, we used a lot of the upstairs rooms and corridors, adapting them to serve as Julian’s living quarters.

“Visually, it was very interesting in some ways but very boring in others. There were a lot of fluorescents in the gym, and I started by adding red gels to those fixtures to see what it would look like. As a backing, we had a big screen with a graphic on it; I lit that with the same red gels I used on the fluorescents. I built the ambience up with the odd Dedolight placed here and there, like if I wanted a red kick behind someone. I also used little red lights beneath the seating areas in the crowd. As my one big toplight, I used a very strange hard light that was already there — it was like an energy-saving mercury-vapor light with a parabolic reflector. I bought another couple of those at the market because I liked the hard shadows that fixture created. I think we used 150-watt clear bulbs in them to let the parabolic reflectors do what we saw the boxing-light doing.

“Other than that, I added various little kicks for the close-ups, which I lit mostly by eye. I just did what I felt looked interesting, or worked to enhance whatever visual elements I saw in the background. I brought loads of colored gels with me from England. I’m very spontaneous in my approach, which is rather ironic given that I worked so closely with Stanley Kubrick [chief electrician on Barry Lyndon, gaffer on The Shining, and cinematographer on Eyes Wide Shut]. He and I were really chalk and cheese in terms of our approach to things. I prefer to be very spontaneous and quick, whereas Stanley’s approach was laborious and test-oriented.”

Because Only God Forgives was Smith’s first digital feature, he hoped to conduct extensive camera tests prior to the shoot, but he found himself hamstrung by circumstances beyond his control. “We didn’t test one frame of footage because we just didn’t have the time,” he says. “I wanted to test the cameras to death so I could truly understand digital [capture and workflow], but a lot of the camera equipment came from Sweden because of our financing arrangement, and it didn’t arrive until three or four days before we had to start shooting. I’ve now shot three movies on digital, so I’ve got a firm handle on it, but if you haven’t used this kind of equipment before and you don’t understand it, you can run into a lot of problems.”

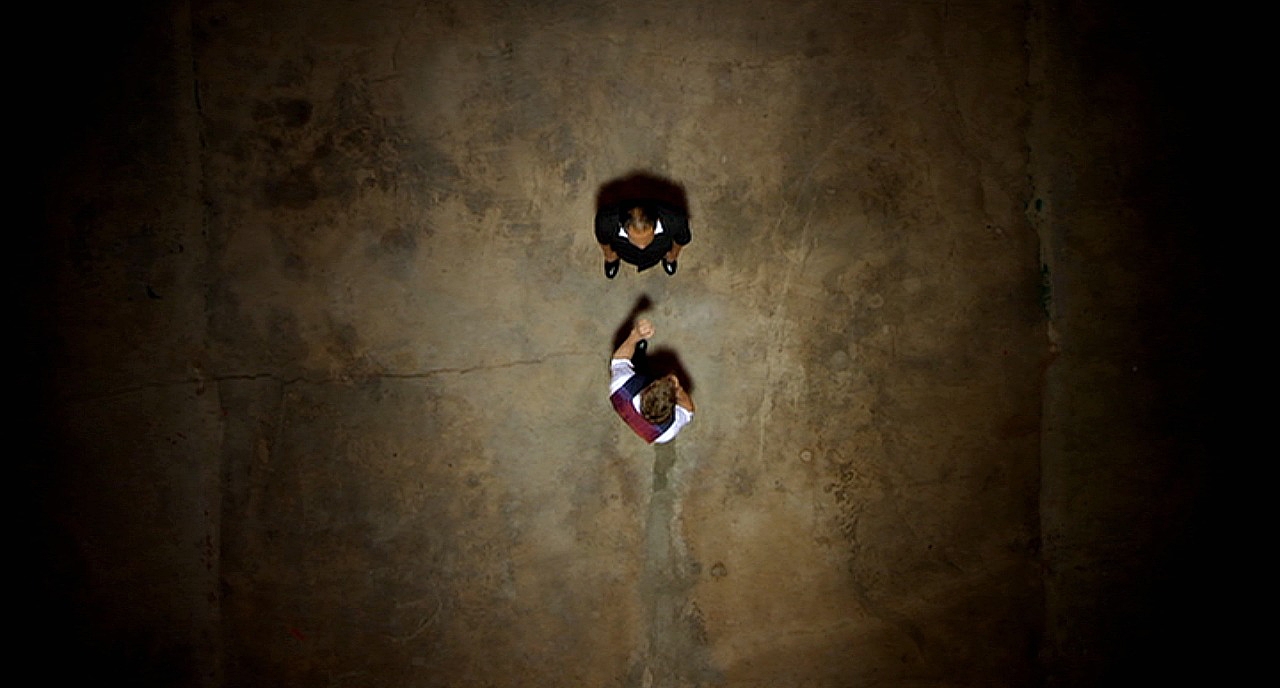

One advantage of digital capture, he says, was that “we were able to shoot quickly and shoot a hell of a lot of footage — we just ran our three cameras all the time. In general, I prefer to use one [brand of] camera all the way through the workflow, because you can run into problems in post if you’re mixing different cameras. We used the Alexa for 70 to 80 percent of the work, and we used the Epic to grab additional shots, including overhead angles for the kickboxing scenes. There is a lot of humidity in Bangkok, but these modern digital cameras are very well built, and we had no problems with them.”

Asked whether the digital cameras afforded him more range for night shots or dark interiors, he replies, “You do get a bit more nighttime exposure, but I wouldn’t say it’s a lot more. You can get the same look on film if you put the right lights in the right places.”

Smith chose softer lenses to mitigate the sharpness of the digital image. “When I shoot digital, I always use Cooke S4s,” he says. “The look of digital is so hard, fierce and unforgiving that you have to use softer lenses, and Cookes are probably the softest. With digital, any little nose shadow can turn into a nightmare.” Alexa footage was captured in ProRes 4:4:4:4 Log C and recorded to SxS cards.

Epic footage was recorded in 5K full frame (5120x2700). The Red’s deBayer settings were mostly camera settings except for gamma, which were set to RedLogFilm. Smith tailored the look by adjusting the Alexa’s color-temperature settings: “When I wanted a warm look, I’d dial it up to 5,600°K, and when I wanted a cool look, I’d dial it down to 3,200°K. A lot of the time I’d shoot in the middle at 4,300°K. One of the pluses of working with digital is that you can dial in a look and see it right there on the monitor.

“A lot of modern directors don’t really understand how what they’re seeing on a monitor will translate to a bigger screen, but Nicolas isn’t like that,” he adds.

To ensure that he and his collaborators get an idea of how their footage will look on larger screens, Smith now travels with a high-end digital projector and a 12'x8' screen to project dailies. “These days it’s the only way I can see rushes,” he says. “Using this system allows me to see the things I’m really looking for. For example, is the focus off on the big screen? Because in six months’ time, when we’re looking at that footage in a post house during the DI, the director may say, ‘Hey, it’s out of focus,’ and he’s not going to remember that you warned him about that on set. That’s especially true if you’re shooting at night with very low light. No matter how many times you’ve shot that way, you want to see that the focus puller understands that he has very little depth, or that the lighting actually works.

“Cinematographers are really handcuffed nowadays,” he laments. “These new formats let us see what we’re shooting very quickly, but somehow, on most movies, we’re still working with one hand tied behind our back!”

Drawbacks aside, Smith produced striking results by exploiting the existing lighting at several locations, including a famous restaurant called the China House. There, the filmmakers staged a memorable encounter between Julian, an exotic dancer posing as his girlfriend, and Julian’s mother, who verbally flays her dinner companions. “That scene was lit almost entirely with practicals,” says Smith. “All the nook lights in the wall behind them were already there as part of the restaurant’s décor; I just supplemented the ambient light with various small fixtures. I placed some Dedos very high over the table so they would hit the white tablecloth and create a bit of a glow beneath the actors’ faces. I also added a bit of light to the entrance where they come in, just to give that moment a little lift.”

In one squirm-inducing sequence, Chang and his henchmen stalk into a karaoke bar and interrupt a party of teenaged girls to brutally interrogate one of Julian’s business associates, Byron (Byron Gibson). After ordering the girls to close their eyes, Chang proceeds to torture Byron with steel skewers, turning him into a human pincushion. “We shot that in Chinatown, in a gay karaoke sex club we transformed to suit our needs,” Smith recalls. “We shot a whole night of that guy screaming, with lots of close-ups of those chopsticks going into his thighs, hands, eyes and ears. I actually questioned the logic of it — I said to Nicolas, ‘Look, this guy would probably die of fear or shock once you put those things through his thighs and hands. He’d definitely be dead by the time you reached his ears. But hey, it’s a movie, so you can do what you want!’ It was quite harrowing to shoot all that. My wife and kids were actually visiting the set when we shot that scene. My kids thought it was alright, but my wife felt it was all a bit much!”

At various intervals throughout the movie, Chang is shown singing karaoke to an audience of his impassive officers at a small nightclub, where low angles show off a ceiling festooned with paper lanterns. “The ceiling in that place was a bit boring, and the production designer, Beth Mickle, thought those small lanterns would add some visual interest,” Smith recalls. “For some shots we turned them on to provide a low glow, and for others we kept them off. They were more a part of the set design. The rest of the lighting for that space was provided mainly by LEDs, plus the spotlight on Chang.”

The crew headed back to the kickboxing gym to shoot the climactic showdown between Chang and Julian, who finds himself overmatched by the older man’s martial-arts prowess. “That sequence was mainly about coverage,” says Smith. “We shot mostly from static positions, capturing every angle and swapping out lenses on all three cameras. The cameras don’t move that often in this picture. We did do some very slow tracking shots for the fight and some other scenes. We laid a lot of track, sometimes up to 100 feet, and it was always in frame. We had to take it out in post.”

“There’s a sense of excitement in tracking shots, which can be used to mechanically emphasize action, exposition or other elements of the storytelling,” says Refn. “I’m also a huge fan of the zoom, which I usually use to say more about the psychology of the characters. In this movie, we used zooms to push Chang away from everyone else, to set him apart as this godlike figure. He takes on mythic proportions, especially during the climax, when we visually equate him to the martial-arts statue that’s visible behind Julian.”

“We didn’t use any handheld camera on this show, and Nicolas doesn’t really like Steadicam,” notes Smith. “He finds any little movement [of the frame] disorienting. We only used Steadicam for a couple of shots after the big restaurant shootout, when Chang is chasing one of his would-be assassins down the street. But overall, there wasn’t much ‘shot choreography’ on this picture. As much as possible, Nicolas likes to do shots with static cameras, and that’s fair enough, because you don’t need to move the camera just for the sake of it. There’s nothing worse than seeing constant camera movement for absolutely no reason. ‘Move when you need to move’ is my philosophy.”

When the final grade for Only God Forgives commenced at Nordisk Film Shortcut in Denmark, Smith was working on another project. Refn graded the picture with colorist Thomas Therchilsen, working in Autodesk’s Lustre 2012 color corrector.

The company also contributed numerous effects shots, including accentuating the film’s bloody mayhem while removing dolly tracks and other production gear when necessary.

[Editor's note: The reel here offers insight on their process, but is also extremely graphic.]

All grading was done from 10- bit HD DPX Log C files transcoded in Smoke from either the original Alexa Log C ProRes files or from the Epic’s 5K .r3ds, which utilized the camera’s original metadata settings and a RedLogFilm gamma setting. In addition to delivering a DCP the graded files were also filmed out at 2K on an Arrilaser 2 to Kodak 2254 intermediate stock, and prints were made on Kodak Vision Premier 2393.

Additional reporting by Jon D. Witmer

1.85:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa, Red Epic

Cooke S4

Smith was invited to became a member of the ASC in 2021.

AC previously spoke to Refn about his bleak historical drama Valhalla Rising (2009) and subsequently covered his collaboration with Tom Sigel, ASC on the thriller Drive (2011) and Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF on the surreal drama The Neon Demon (2016).

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.