5-25-77: An ASC Odyssey

A long-gestating indie feature about the joy of filmmaking was partly inspired by the Society and its flagship magazine.

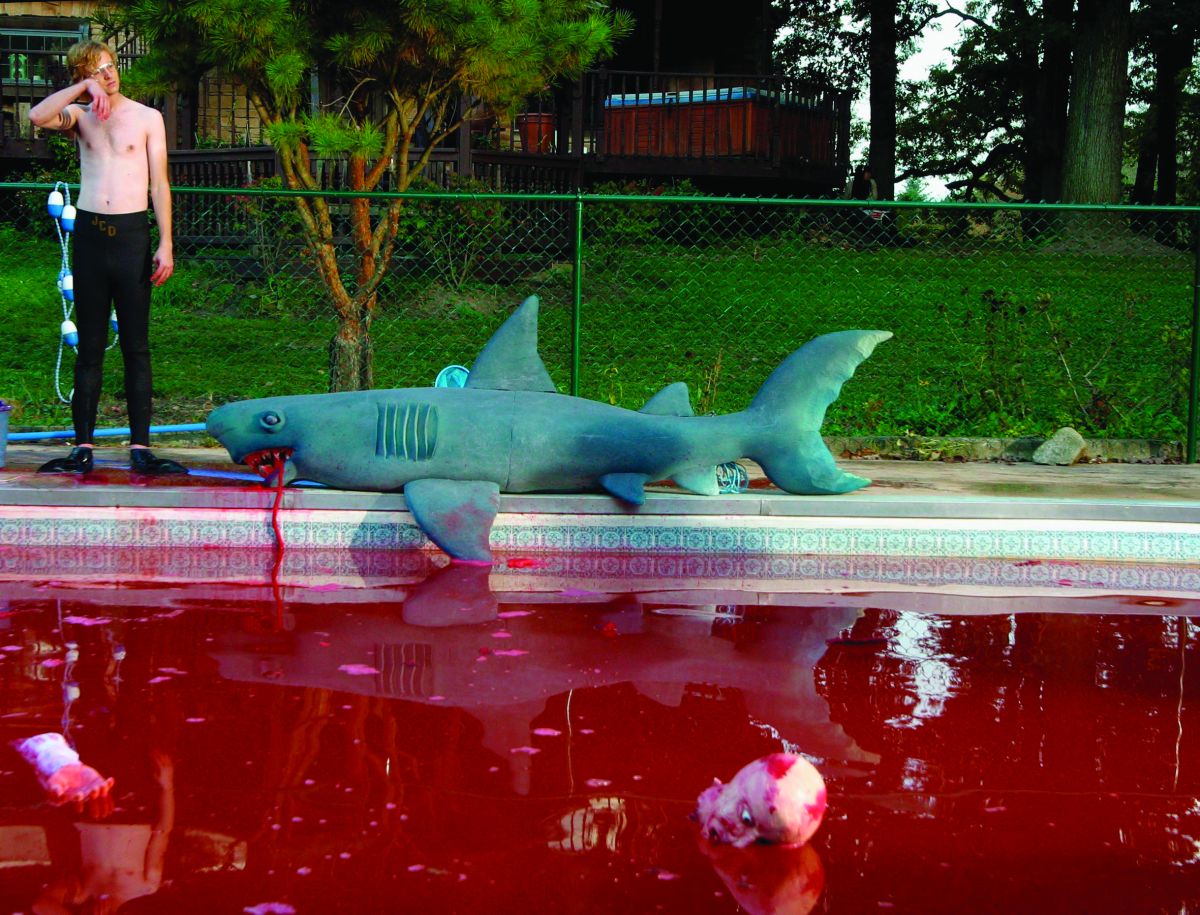

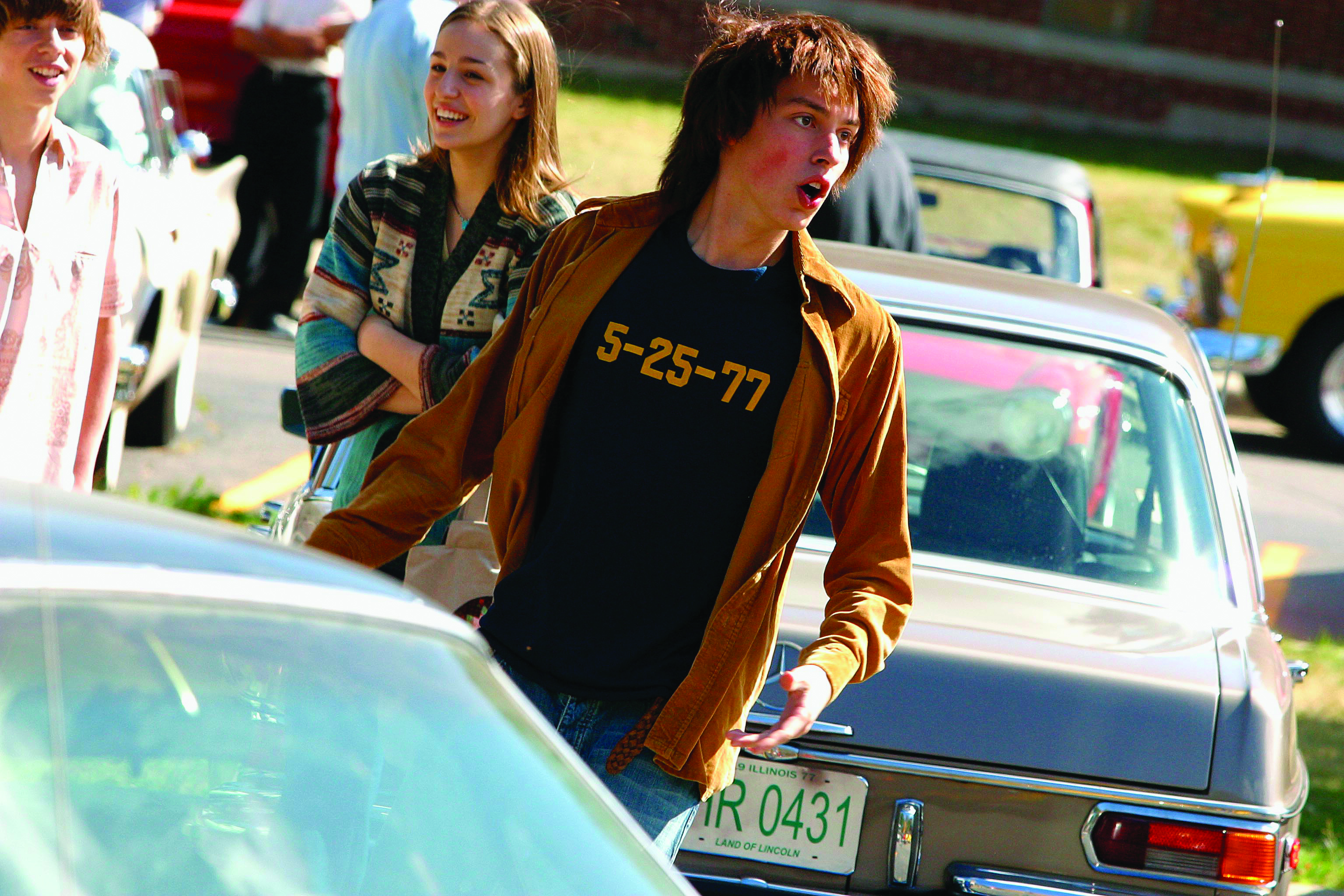

Images courtesy of Patrick Read Johnson and MVD Entertainment Group

Patrick Read Johnson was not the first budding filmmaker to arrive at the ASC Clubhouse in 1977 with a reel, a reverence for Kubrick’s 2001, and an encyclopedic recall of every issue of American Cinematographer he’d struggled to procure in his rural hometown, but he was nevertheless unique.

He was 15.

Tucked under the boy’s arm was a VFX-heavy Super-8 oeuvre that had become the talk of the town in Wadsworth, Ill. His proactive mother, recognizing a passion that could not be developed (or even fully understood) locally, had flipped open a copy of AC and cold-called the magazine’s editor, Herb A. Lightman, in search of career advice for her son. When Lightman offered some encouraging words — it was Hollywood, after all — she sent the boy to L.A. for his spring break.

“I showed up at the Clubhouse and introduced myself, and Herb’s jaw dropped — my mom hadn’t told him I was coming!” Johnson recalls. “He said, ‘Oh! Well, we can’t leave you out on the street.’”

Hollywood Connections

Lightman proceeded to arrange interviews with some of the leading icons in special photographic effects, among them Douglas Trumbull and ASC members Linwood Dunn, L.B. “Bill” Abbott and Frank Van der Veer. “Herb’s idea was that he would interview them and I would observe,” says Johnson. “He introduced me as ‘a kid from the Midwest who makes little movies,’ and they were charmed, I think because so many of them had started that way.”

in the offices of American Cinematographer, editor Herb A. Lightman (Austin Pendleton) has a phone chat with the budding auteur’s mom Janet (Colleen Camp, below)

Lightman’s tour of the industry came to include a spontaneous chat with Steven Spielberg, who was working on Close Encounters of the Third Kind at Future General Corp. when the pair came looking for Trumbull — and a visit to a certain VFX start-up out in the Valley that was frantically trying to finish a movie called Star Wars. There, a young visual-effects cinematographer (and future ASC member) named John Dykstra greeted Lightman with an apology. Johnson recalls, “Someone had burglarized Lucasfilm’s office the night before and stolen boxes of photos and transparencies — basically the entire visual record of what ILM was doing. So, John said, ‘I’m sorry I can’t give you anything you can use in the magazine, but I’ll walk you through the shop and show you a couple of clips.’ Well, he showed us the opening scene, then the next scene, then the next …. He kept saying, ‘Now watch this next part!’ Two hours later, we’d seen the whole movie, complete with grips in shot, World War II dogfight footage and storyboards cut in. It was half horrifying and half the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.”

Industry Ambitions

It was a week that changed Johnson’s life, illuminating a potential career path and sparking friendships that would blossom when he moved to Los Angeles several years later to begin working in the industry. And many of those colleagues came into play on Johnson’s semiautobiographical coming-of-age comedy, 5-25-77, which follows young Patrick Read Johnson (John Francis Daley) from his film-crazy childhood in Wadsworth to his departure for Hollywood after he sees Star Wars, motivated by the interlude with Lightman (Austin Pendleton). Though the movie takes its title from Star Wars’ original release date, Johnson actually had a different George Lucas film in mind when he conceived it. “I wanted to make an American Graffiti for my generation,” he says.

An independent feature nearly 20 years in the making, 5-25-77 ultimately involved three cinematographers: David Blood, Ken Seng and Scott Ressler. (A fourth, Shaw Fisher, assisted more recently in myriad ways, including with the color correction.) In 2004, after lining up Chicago producer Leigh Jones, Johnson began shooting the Illinois-based production in Wadsworth with Blood at the camera. The original financier vanished as that work was wrapping up. “We’d spent $180,000 and had 75 percent of the movie, but no Hollywood sequence,” says Johnson. “So, we cut footage together with a 25-minute ‘Scene Missing’ card in the middle of it and started showing it to potential investors. It was very effective, because they could immediately see that what was missing was necessary.

In 2006, with new financiers aboard and another $750,000 in hand, Johnson resumed shooting, this time with Seng. “We’d shot all the Midwest scenes on Super 16 spherical, and I wanted California to look great — I wanted 35mm anamorphic,” Johnson says. “I told Ken the lenses should be the most aberrant, flaring … I said, ‘I want problems!’ And he brought out these old Russian anamorphics that were perfect. They were clunky and chunky and felt like the time.”

The ASC Gets Its Close-Up

The key Hollywood interiors, including Lightman’s office at the ASC, were filmed in a defunct toy store outside Chicago. “It had been stripped down to its industrial basics, which was perfect for the look of Future General and ILM,” notes Johnson. “For the sequences in both of those places, somebody mounted the lens a degree or two off of vertical, so the anamorphic distortion is slightly tilted to the left, like a Dutch anamorphic. I thought about correcting it [in post], but then I thought, ‘It’s Pat’s memory, why perfect it? Leave the rough edges.’ So we did.”

Though a three-walled set was built for Lightman’s office, the larger ASC Clubhouse interiors were shot in the actual building during two shoots some 10 years apart. Ressler was at the camera for both of them.

The 2001-inspired sequence takes a spacesuit-clad Patrick into the Clubhouse, through the foyer and to the door of Lightman’s office. “The Clubhouse interior has a formality to it not unlike the hotel in 2001,” Johnson says, “and I thought, ‘I can make it the bedroom at the end of the universe because it’s literally where Pat is going to find out if he gets to move to the next level.’

“Initially, I never dreamed we’d have a chance to shoot in the Clubhouse,” the director continues. “We got permission to spend a day filming the exterior in 2006, and while we were doing that, Ben Toguchi, the elderly caretaker, actually recognized me from my original visit! He said, ‘I remember you! You’re that kid Herb took all over the place.’ I couldn’t believe it. I told him what we were doing, and he said, ‘Why aren’t you shooting inside? Come on!’ And he opened the door and let us in. We did a couple of quick shots in the foyer, improvising completely, and then ran away.”

With a laugh, Ressler recalls, “I kept thinking, ‘Are we supposed to be in here?’ We had a film camera and an anamorphic wide-angle lens from Panavision. At one point, Patrick wanted a handheld POV shot as Pat’s walking, and I did not have any handheld equipment, so it was tricky to get that. There might have been a fixed eyepiece, but it was so long ago I can’t remember. We had a lighting kit in the car, but we didn’t take any lights inside out of respect for the institution. It was available light.”

After performing further edits on the film, Johnson realized he needed a few more shots in the Clubhouse, and “the ASC graciously agreed to let us back in,” he says. This material was captured in 2016 with Johnson’s Sony a7S II, with Ressler and Fisher working in tandem. “We filmed an exterior sequence out front with doubles [for Pendleton and Daley],” says Ressler. “We also did various shots of the interior, including Pat’s double in the spacesuit for later face replacement.”

A Professional Finish

Relationships Johnson forged over the course of his career, which began with jobs in model shops and evolved into directing (Spaced Invaders, Baby’s Day Out, Angus), helped him achieve an impressive degree of verisimilitude in 5-25-77. For example, for the Close Encounters set-visit scene, Richard Yuricich, ASC loaned Johnson his original matte paintings and advised on the “cloud tank” work, while Greg Jein loaned the filmmaker his Devils Tower model and mothership miniature; for the ILM sequence, Star Wars producer Gary Kurtz and longtime ILM visual-effects supervisor John Knoll helped to facilitate Lucasfilm approvals.

But the relationship that started it all was with AC and the late Lightman, who edited the magazine from 1966 to 1982. “Herb was the moment, the connection, the nexus and the spark,” says Johnson. “He opened the door, saw this goofy kid standing there and didn’t slam it shut. And he could have — easily.”