A Simple Plan: The Root of Evil

Director Sam Raimi and cinematographer Alar Kivilo, CSC adopt an austere, unaffected style for this psychological thriller that explores the insidious influence of dirty money.

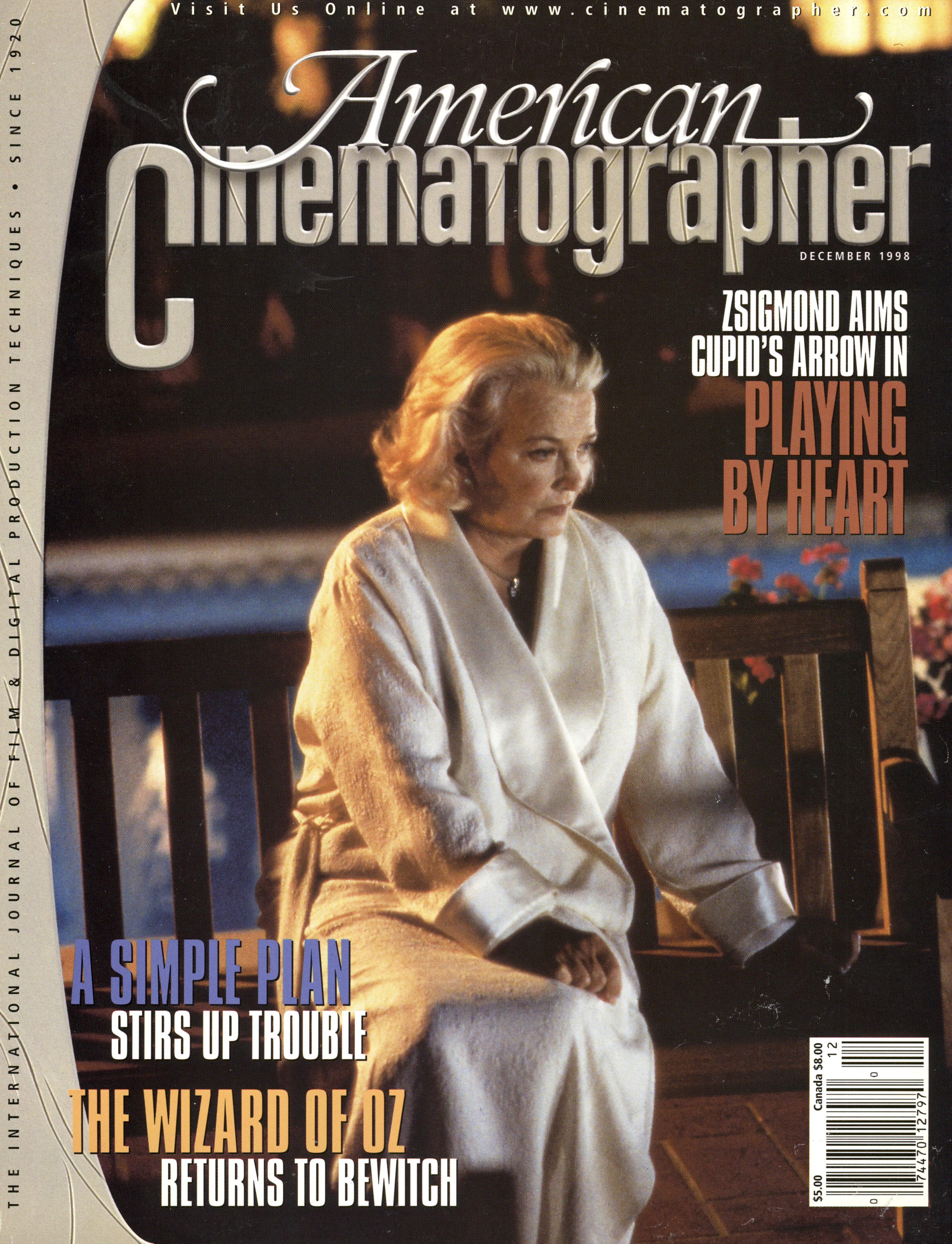

Unit photography by Melissa Mosley

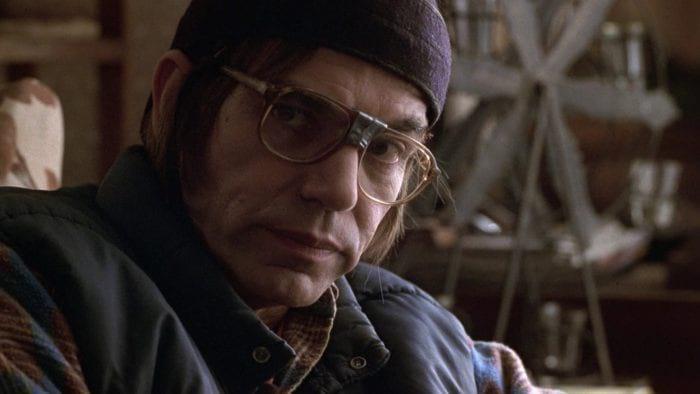

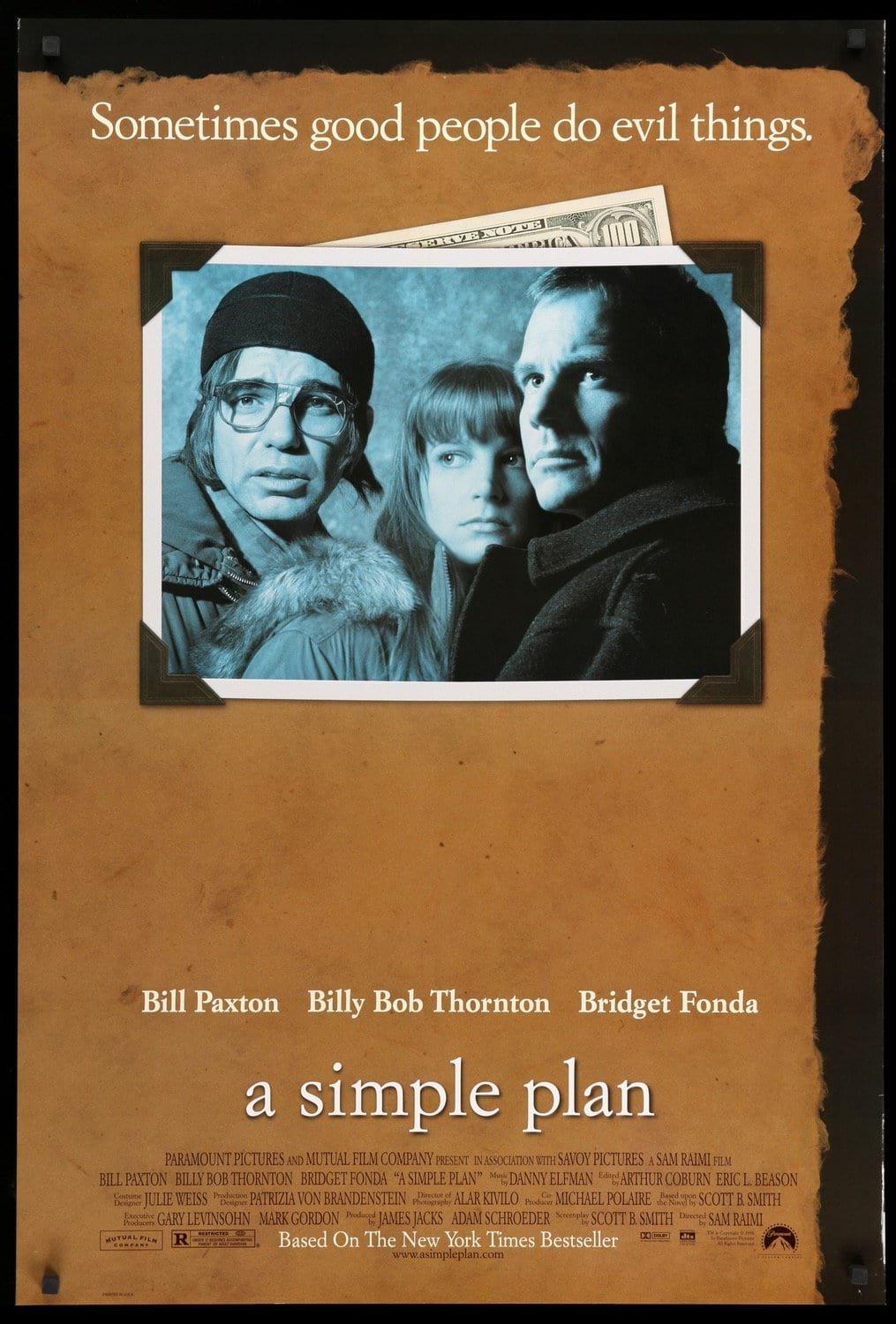

In A Simple Plan, the quiet existence of two country brothers is transformed into a maelstrom of deception, paranoia and greed when they discover over $4 million in a downed plane. The subsequent lure of instant wealth and a well-heeled life leads Hank and Jacob (Bill Paxton and Billy Bob Thornton) into a downward spiral, as their seemingly sensible notion to keep the money and avoid detection triggers a chain of events that quickly lead to dire consequences.

In his latest picture, director Sam Raimi makes a considerable departure from his visually dynamic fantasy-film repertoire (which includes the Evil Dead trilogy, Darkman and The Quick and the Dead) to create a grounded psychological thriller fraught with moral questions. “This film is definitely a change of pace for me, because it’s not about shots, but the performance within the frame,” Raimi explains. “I wanted the camerawork to be invisible, and tried to allow the actors to tell this very thrilling story."

"The thing that attracted me to A Simple Plan is the fact that the hero is an everyday fellow I can relate to. The great characters that Scott Smith created, both in his book and in his screenplay, are people that I know. These aren’t bad guys. They’re just human beings who make a rash decision and have to live with the consequences; they have to fight to get out of this slowly tightening noose that the money has created around them.”

In striving to tighten the noose artfully, Raimi teamed up for the first time with cinematographer Alar Kivilo, CSC, a veteran of both television and independent film whose work on the HBO production Gotti earned him a Cable ACE Award, as well as ASC and Emmy nominations. Kivilo’s other works include Weapons of Mass Distraction, Rebound and the mini-series The Invaders, which netted him an ASC Award nomination. “I was in Toronto doing a commercial, and I read the script for A Simple Plan on my day off,” recounts Kivilo. “I got so excited that I called my agent at home and made him arrange a meeting with Sam Raimi. I love character-driven stories. I like the fact that are so many different levels to A Simple Plan. There is a great double arch between Hank and Jacob that really brings depth to the film. I’m attracted to projects that actually say something and deal with real people and real emotions.”

Kivilo joined the production team just three short weeks before principal photography was scheduled to begin. He quickly found himself immersed in the details of a distant location shoot in Delano, Minnesota. He credits the success of this rapid deployment to his crew: “I was able to bring along the key | members of my team, which was very important to me. My gaffer, Elan Yaari, my key grip, Joseph Dianda, and my operator, Monty Rowan, were my backbone, and absolutely essential to the film.”

“[Visually,] this film was a big departure for Sam, who is really known for his crazy camera moves and wild perspectives. We both decided early on that his usual style wouldn’t be right for this story.”

The duo agreed early in prep to abandon the director's trademark style of wild camera moves and in-your-face cinema.

The cinematographer found inspiration for the look of the film in photographs that were shot during the location scout in Delano, prior to his arrival on the show. “I was very taken with the location photos that I saw in my initial meeting with Sam,” Kivilo recalls. “All of the shots were very stark, with white snow and black trees. They were very hard-contrast, and reminded me of Japanese woodcut prints, with very simple and graphic images. [Visually,] this film was a big departure for Sam, who is really known for his crazy camera moves and wild perspectives. We both decided early on that his usual style wouldn’t be right for this story.”

A primary requirement in Kivilo’s choice of film stocks was speed, since the winter days in Minneapolis were exceptionally short. The cameraman did extensive tests before traveling to the location. “I needed a film stock that would maximize my day for me,” he explains. “I ended up choosing [Eastman Kodak] 5246 [Vision 250D] for all the daylight scenes and 5279 [Vision 500T] for the night scenes. I also tested the 5274 [Vision 200T], 5245 [EXR 50D], and 5277 [Vision 320T]. The 5245 and 5274 were too slow for us to maximize our day, as we literally had only eight hours of usable light and [using a slower stock] would have limited that time even more. I found that the 5277 really held up the detail in the white snow quite well, which was nice. But it lacked that starkness that we were going for, so 5246 won out.”

Further complicating A Simple Plan's short pre-production schedule was a ripple effect of the infamous El Nino weather anomaly, which led to an unusually warm winter in Delano that left very little usable snow on the ground. The production was forced to move to Ashland, Wisconsin and begin photography there, again shortening the amount of time that Kivilo and Raimi would have to plot their photographic approach. “We really didn’t have much chance to narrow down visual specifics,” the cameraman explains. “Sam loves to storyboard everything, so terms of the film’s look, we began with a rough visual sketch in storyboards. I tried to sit in with him and storyboard as much as possible during those three weeks, but once we got onto the set, we’d switch to a more traditional approach and block the scenes with the actors first to see where their instincts took them. We would then apply the storyboards, modify them, or throw them out, according to what the actors would be doing. I always like to see the actors play the scene and discover where their feelings lead them. Sometimes they’re bang on, and sometimes not, but you generally have to take their instincts into consideration when you’re covering a scene.

This whole project was kind of an exception to my normal style,” Kivilo continues. “I usually like the photography to have an arc of its own, where it starts off one way and you discreetly increase the drama. For example, as a character becomes more evil, I’ll move to wider lenses or spookier lighting or something. However, the changes that the characters [in this film] go through are extreme, so I decided to keep the photography very neutral and never comment on what was going on in the scene. I approached the whole project in a very naturalistic way. I picked relatively neutral lenses, gravitating toward the middle range. As a rule, we kept away from the really long or wide lenses. Our real workhorse was the 40mm, which happens to be my favorite. It’s great for moments of drama, and for doing close-ups. It’s wide enough for master shots, but it doesn’t distort even if you get close to the subject. It’s the last lens going toward the wide end in which the lines of the architecture remain straight. Again, we were constantly trying to hew to that simplicity.”

Kivilo chose to shoot A Simple Plan with a Platinum camera and a selection of Primo prime lenses from Panavision Chicago. “Sam and I had talked briefly in the beginning about going anamorphic,” the cameraman says, “but because of the lack of prep time, a restricted budget [reportedly $17 million] and lack of lens availability, we decided against it,” he reveals.

When the crew returned to Minneapolis from Ashland, they still found themselves plagued by a lack of snow. To solve this problem, the production put together a small group whose sole responsibility was dealing with snow. “They moved snow from one place to another and did whatever was necessary to maintain the look and continuity we needed,” Kivilo explains. “In conjunction with the special effects people, they used a combination of real and synthetic snow. Primarily, the unit made their own snow from shaved ice, which made the best match for the real stuff. Anything else was fine to fill in the background, but when we were close, the shaved ice was the best. Of course, another difficulty of shooting in the snow is that every time you do a take, you have to get rid of the footprints. To do that, the ‘snow unit’ marched around armed with gasoline-powered blowers, rakes and whatnot to erase footprints and make the snow look virgin again.”

A Simple Plan opens on a New Year’s Eve afternoon when Hank and Jacob take a trip to their father’s grave, accompanied by Jacob’s slovenly friend Lou (Brent Briscoe). Their return trip is inadvertently detoured when Jacob’s dog takes off into the forest after a fox. As the trio venture into the woods to retrieve the dog, they stumble upon the wreckage of a small aircraft.“Outside, our basic plan was to hope and pray for overcast weather,” Kivilo says, laughing. “We wanted to avoid blue skies and sun, and we were lucky for the most part. On overcast days, I would simply employ some negative fill so that the light wouldn’t bounce around as much from the white snow. We covered the ground with solids and brought in more solids on one side to give the light more direction. Then, for closeups, we’d shape and refine the light slightly with a bit of bounce fill off a card. During the few days when the sun did come out, I wanted to bring in a big crane with a huge silk to take care of the situation, but again, budgetary factors didn’t allow it.”

Raimi and Kivilo instead turned to digital technology to pick up where nature left them short. “We’ve replaced all of the blue skies with CGI [cloud cover],” Kivilo explains. “Also, sometimes when we were moving into coverage, it would start to snow, or stop snowing, and we’d have a continuity problem. CGI effects were a real lifesaver in those situations as well. There is a certain compromise involved when you’re doing drastic changes in CGI — like making a bright sunny day into an overcast day — because it never really looks quite the way it should. But digital effects certainly do help to bridge the gap.”

Part of the film’s signature visual style resulted from Kivilo’s graphic approach to the daytime exteriors. The stark, almost blinding whiteness of the snow is a refreshing departure from the traditional, slightly blue, cold look. “I was letting the snow go about three stops over,” the cinematographer offers. “I was usually exposing at about an f5.6 outside, but the snow would be reflecting back an fl6 or more. By overexposing it that much, the snow gave us really blinding whites and we’d lose detail, which for most applications was great. However, there were a couple of scenes in the film in which footprints in the snow were an important element of the story. Because of the overcast conditions and the contrast created by the way I was exposing, we would occasionally have to paint in the foot prints to make them readable. Someone from the art department would walk backward through the footprints with water-based spray paint and darken in the shadow side of the prints so they would read better.

“To keep the visual look simple, we were also constantly pruning the vegetation, getting rid of trees and simplifying the actual locations elements. We tried to stick to that Japanese wood-cut look, which is almost monochromatic. The film is such a grim, cautionary tale that we wanted it to have a nearly black-and-white feel to it.”

As the tale’s central trio begin to explore the downed plane that remains partially buried in the snow, Hank ventures inside and discovers more than just a nest of crows and the remains of the pilot — he uncovers a large duffel bag stuffed with bundles of cash. To shoot the aircraft interiors, the production moved into a soundstage in Minneapolis, and recreated the snowy surroundings to allow greater control over the situation. “In order to facilitate not only the camera squeezing into the tight spaces of the plane, but also the puppeteers and the animal handlers who were dealing with the animatronic and live crows inside, we wound up placing the fuselage on an elevated platform about five feet off the stage floor and cutting several holes in the bottom of the plane,” Kivilo reports. “For the interior shots, I tried not to take undue advantage of the fact that we were on a stage, so I primarily used the light that came through the windows of the plane.”

Gaffer Elan Yaari details the setup, explaining, “We hung a 40' by 40' overhead muslin bounce about 25' above the floor and pumped a bunch of HMIs into it — 18Ks and 6Ks — to give us a basic ambiance level, which was pretty close to the f5.6 that we had outside on location.”

“I continued to use the 5246 while shooting inside, maintaining continuity with the exteriors, so I was fighting to get a decent exposure with 250 ASA,” Kivilo says. “The challenge became providing enough light [outside the plane] for my main source of illumination inside, while at the same time controlling the windows so they wouldn’t burn up too much. I had to play with the ratios a bit inside. When we were seeing a window, I’d use the off camera window for the key and then cut down the on-camera window with more snow, ice, and nets outside so that it wouldn’t blow out in the frame. I used Kino Flos to augment what was happening inside for a few shots, but for the most part I let the windows do the work. I was trying to keep it as real as possible and stay far away from something that looked as if it was shot in a studio.”

Once they discover the money, the three men argue over the prospect of keeping their find. A decision is finally made and the trio spends hours carefully counting their haul before heading home. Night has fallen and they are met on the roadway by the town sheriff, Carl (Chelcie Ross). The men frantically hide their treasure from the lawman, and the tension begins to rise — along with their feelings of deviousness and paranoia.

Faced with the prospect of lighting this large night exterior — surrounded by a blanket of white snow and without any justifiable means of practical illumination — Kivilo turned to a fairly new tool with mixed results. “Maybe this is a good cautionary tale in itself,” he offers. “We used a helium balloon light for the night exteriors on the roadside. It was a logistically tricky location because we were on a small road with two snow fields on either side, so there was no place to drive in a crane or a Condor. The balloon seemed to be a perfect solution. We could fly it up so that it would hover just above the road, and then hide the black cable in the night sky. What I didn’t expect was that it got really windy during the night we were shooting. I was operating the second camera, looking at the wide shot of the sheriff’s truck approaching, and as the wind was gusting I kept seeing the balloon getting lower and lower in the frame. It never quite dropped into the picture area, but it made me very nervous. Then, at one point in the middle of the first take, the wind blew the balloon into a power line and it made a huge spark. Thank God no one was hurt and there was no damage, but we did lose quite a bit of time. We really hadn’t factored the wind into the equation, and because of the white snow surrounding the area, we really couldn’t attach extra lines. I thought the light that the balloon provided was perfect — a nice ambient glow and a beautiful night softness — but I was very uncomfortable with it after that first night. On the second night, when we returned to shoot the reverses, I went with a more traditional approach.”

Gaffer Yaari explains, “We lit the second night by bouncing an 18K and Maxi Brute off of a 40' by 40' muslin. We put it about 30 or 40 feet away and left both instruments clean to combine the 5500°K and 3200°K for a slightly cool mix.”

After their encounter with the police officer, the three men go their separate ways, vowing not to tell a soul about the existence of the money. Hank is the first to violate this pact, returning home and immediately asking his wife, Sarah (Bridget Fonda), what she would do if she found a substantial amount of seemingly unclaimed money. Sarah protests, taking a strong moral stance until Hank dumps the $4 million dollars on the dining room table. Faced with real greenbacks, her morals quickly crumble.

Kivilo chose to illuminate these interiors in a very warm and intimate style. “There was something intriguing about a nice, warm, uncorrupted home, with a normal husband and wife expecting a little child, being invaded by this evil,” he muses.

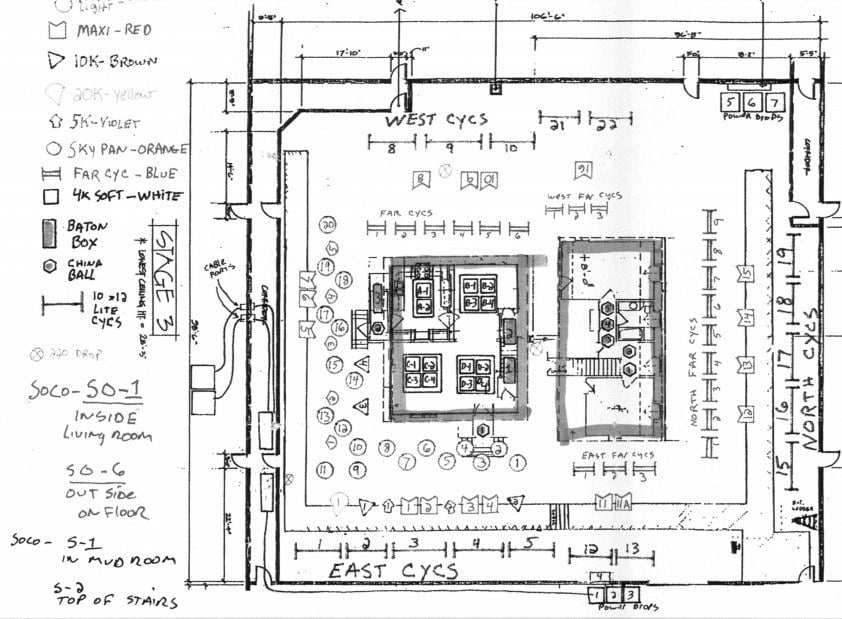

The Mitchell house was built on stage in Minneapolis, where production designer Patrizia Von Brandenstein (an Academy Award winner for Amadeus, who had previously collaborated with Raimi on The Quick and the Dead) accentuated Kivilo’s lighting strategy with comfortable surroundings that stood in contrast to the looming threat that would eventually consume the family. Yaari details, “We pre-rigged the whole stage so that no matter where Alar wanted to look, we were prepared. Practically the whole stage was on dimmers [see diagram further down this page]. My ideal scenario was to have everything on a dimmer — not necessarily to control exposure, but to be able to turn fixtures on and off quickly. Instead of a half-hour of down time between setups, it might take five minutes to switch over the channels and adjust the floor instruments a bit.

“I hung a couple of Maxi Brutes at any opening off the greenbeds — doors or windows — and diffused them with a layer of opal and then a 6' by 6' piece of bleached muslin. We’d turn those on for the daylight scenes and get about an f2.8 in the windows — just a nice soft glow. [Key grip] Joey Dianda’s team had to tease the Maxis pretty heavily to keep spill off things, but at about 20' away, they really gave a beautiful light. We put those on the dimmer board as well, through a whole rack of 12K dimmers right next to a rack of 2.4K CD-80 dimmers for the floor lights and practicals.

“For the night scenes, every now and again I’d bring in something hard, like a cool 10K with Vi blue on it, and play it a stop or two under key through a window. Over the sets, Alar had us hang softboxes that were made up of four 4K soft lights hung over 6' by 6' bleached muslin. Again, softness was the key and the 4Ks were all run through the dimmer board. I could bring up three or four units and we were ready to go. We used a bit of coloration for the interiors, sometimes ¼ or ⅛ straw, and most of the practicals were dimmed down to about 75 or 80 percent. For the floor keys, we would use two Kino Flo Image 80s — one on top of the other — as one source. We’d then put on a couple layers of diffusion, like an opal, 250, or light gridcloth, depending on the mood, and then an 8' by 8' or 12' by 12' piece of bleached muslin. The Kinos are soft to begin with, but they’ve got a little bit of edge, so if you put any kind of diffusion in front of them it quickly gives them the feel of a bounced source.”

For moodier moments, Kivilo used hard light reflected into the sets using beveled mirrors. “I’d pick a dead corner of the set and have Joey black it out so no light was there,” The cameraman explains. “I’d then aim Par cans or sometimes HMI Pars into the mirrors and splash light into random spots on the set. I’m always searching for the best kinds of slashes, which have an organic feel, and these beveled mirrors provided that. It was perhaps the only slightly stylized addition I made to our otherwise simplistic regime, in that there was no logical source for that kind of light; my thinking was that it was perhaps coming from a streetlight outside or something. Those scenes were about mood, and it was great to use the mirrors rather than backlight an actor. I’d just bounce a slash into the background and silhouette them against the set.”

In fact, an interior scene offers one of Kivilo’s favorite shots in the picture.“It takes place late in the film, after the sheriff has found Jacob drunk at the scene of a grisly double murder,” the cameraman says. “The sheriff brings Jacob to Hank’s house and Hank puts him into the baby’s room on a day bed. We had the camera right on the deck below Jacob, with a 40mm lens looking up at him with Hank standing in the background. We’re in this warm, comfortable room that’s been invaded with emotions of paranoia and guilt, and Jacob asks, ‘Do you ever feel evil, Hank? I do.’ I like that moment. It’s the contrast of the visual elements with the psychology of the story at a very low point in the character’s lives.”

For a key scene that thrusts the brothers miles past the point of no return and results in the death of not only Jacob’s friend Lou, but his wife, Nancy (Becky Ann Baker), the filmmakers chose an abandoned house in Minneapolis. “It was a very difficult location,” Kivilo recalls. “It was an abandoned house with very low ceilings and no heating, so we were all bundled up in parkas. Because the performances were so intense, Sam wanted to shoot the scene with at least two cameras, and sometimes three. Lighting for three cameras is a significant compromise, but it was one I was willing to make to lessen the emotional load on the actors.

“After Lou is shot, Nancy runs into a dark kitchen, where I had pre-established a bit of light coming through a window to silhouette her as she runs to a drawer. Hank steps into the kitchen and is also silhouetted [by the light from the living room]. He turns on the kitchen light to reveal Nancy holding a gun; she fires and hits the light switch, which, after a great spark, thrusts the whole kitchen into darkness again. She shoots several more times, with the muzzle flashes providing sketchy details of the encounter, until Hank fires his shotgun and kills her.

“The idea was to keep things quite sketchy in the lighting and not be clear about exactly what was happening. For the overall kitchen light, we hung a China ball from the ceiling, which would reveal Nancy with the gun. Two prop guys — one facing Nancy and one sneaking in toward Hank — used those old flash photo guns to create the muzzle flashes. Those flash guns are great because they have a long burn time and you don’t run the danger of having the flash occur between exposures. The flashes were daylight t-balanced, but we put double CTO on them to give them a slightly warmer feel. This was something that we had determined through testing in pre-production.

“This is a tricky film to talk about,” Kivilo concludes, “because the whole visual approach was to keep it simple and not obstruct the story. It’s all about the aesthetics, and we really tried — especially on the exteriors — to keep that Japanese wood-cut aesthetic going.

For A Simple Plan, it was a simple shooting style.”

This stage plot, drafted by gaffer Elan Yaari, depicts the hanging rig for the Mitchell house built on stage in Delano. The leftmost structure is the bottom floor of the Mitchell house, with the kitchen at top left, dining room at top right, living room at bottom left and the entryway foyer at bottom right with the stairs proceeding to the second floor.

Above each area of the first floor are 4K softlights (designated A-1 through D-4) were controlled by the dimmer packs indicated by two rectangles in the corridor at the bottom left of the diagram. Just inside the walls of the stage, the production circled the sets with four photographic backgrounds. The leftmost background was lit with 12 6K Space lights (indicated by green circles, numbered 9 to 20) augmented by five Sky Pans (orange ellipses numbered 1 to 5). For the daylight sequences, two Maxi Brutes punched over the photographic background and through opal and bleached muslin through the window just above the sink in the kitchen (indicated by red pentagons 6 and 7), while another (number 5) played through a window in the living room along with two lOKs with Chimeras (brown triangles numbers 3 and 4).

Outside the kitchen, the art department constructed the brick facade of the neighboring house. The 10-Light Cyc units, originally designed to backlight the photographic backdrops (labeled “East Cycs,” “West Cycs,” and “North Cycs”) were eliminated in favor of fontlighting the drops with Far Cyc units (numbered in sections “Far Cycs” 1 to 6, “West Far Cycs” 1 to 3, “North Far Cycs” 1 to 9, and “East Far Cycs” 1 to 3).

For the upstairs of the Mitchell house (the rightmost structure highlighted in green) Yaari and cinematographer Alar Kivilo again played Maxi Brutes through the windows (numbers 11, 11A, 12 to 15, and 16) and used China balls for the hallway illumination.

For the nighttime look, Yaari would turn off all of the Maxi Brutes, Space Lights, Sky Pans and Far Cycs, except for one or two, to achieve roughly a 4' lambert glow off the drops, just enough to read a hint of the drops through the windows. “We wound up pulling in both of our 1200 amp generators off the trailer,” explains Yaari, “as well as power from the cans on stage and the stage next door so that we had around 6500 amps. We never had everything burning at once, but the idea was to have everything ready at the flick of a switch.” — Jay Holben

Recommended by ASC members Steven Poster, Mark Irwin and Robert McLachlan, Kivilo would go on to become a member of the ASC in 2003. He is also a member of the Estonian Society of Cinematographers. He published a career-spanning memoir in 2021.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.