Alter Ego: The Talented Mr. Ripley

John Seale, ASC, ACS re-teams with director Anthony Minghella on this scenic psychological thriller.

This article originally appeared in AC Jan. 2000

Unit photography by Phil Bray

Most of us have been disappointed with ourselves at some point. We’ve all felt inferior. We’ve all been at the edge of things and wished we were someone else,” contends writer/director Anthony Minghella (an Academy Award-winner for The English Patient). “It’s a feeling we can all empathize with, and that’s what really fascinated me about the story for The Talented Mr. Ripley — the idea of wanting to exchange your identity for someone else’s. Wanting to give yourself up completely and become someone else is a deep desire that stems from some inner discontent, some self-dissatisfaction, and even a self-loathing that is basic to human nature.”

After a concerted effort, producers William Horberg and Tom Sternberg finally secured the rights to Patricia Highsmith’s novel (which had previously been brought to the screen in 1960 by French director Rene Clement, under the title Purple Noon) for Sydney Pollack’s Mirage Enterprises. They then asked Minghella to pen the adaptation for them. The writer/director fielded the offer during a long lull in preproduction on The English Patient, and agreed to take on the job. “I liked the book very much, and I thought that I would simply write the screenplay,” Minghella recalls. “However, as soon as I began to work on the book, I became obsessed with making the film, and very reluctant to relinquish my grasp on it. Mirage and Paramount were kind enough to wait until I finished making The English Patient before seriously discussing the fate of The Talented Mr. Ripley. I then spent about a year revising the script, and became more and more passionate about directing the film.”

In the wake of their enormously successful partnership on The English Patient, Minghella and cinematographer John Seale, ASC, ACS (who earned an Oscar for his photography) decided to reteam on Ripley. “John has been a very significant partner for me in filmmaking,” offers Minghella. “The type of filmmaker that I am now has evolved from working with him for several years and learning a great deal from him. One of the cleverest things I’ve done as a director is to surround myself with people who do their jobs much better than I do mine. I’ve managed to draw upon the experience from very significant collaborators like John, and I’ve managed to learn as much from them as I have from the actual experience of shooting.

“I have enormous regard for John as a cinematographer,” Minghella continues. “As a fellow director, he is a man of few words. In my very noisy team of collaborators, he is by far the least noisy of them. But he is absolutely a doer, and he’s most happy when he’s shooting. One of the things I’ve learned from him is to have no fear about shooting. If we equate filmmaking to fighting a war, he’s definitely a soldier I want with me in a battle, because he’ll never give up. He plays down his artistry in favor of his artisanship, in the sense that he’s not somebody who wants to debate the artistic merits of the moment. He doesn’t want to invade my process and make the film for me; he’s there to help me get it done.”

“As a cinematographer, it’s my job to get on the director’s visual and narrative wavelength.”

Seale, who attributes his filmmaking approach to his experiences on low-budget productions in his homeland of Australia, concurs. “You should never be fighting to make your own movie. As a cinematographer, it’s my job to get on the director’s visual and narrative wavelength. Every film should be totally different, and you should have a blank, open mind as you go into it. I feel that if I carry a personal cinematic style with me on to every film — just because it looks good — I’m making a mistake. Every film is a new visual experience that evolves out of working with the director and dealing with the locations, the weather patterns, and so on. To a certain degree, all of those factors are going to take control over you. In the end, though, you’re making the film for the director, and he or she should always be supported. Good or bad, I’ve stood by that methodology, and I believe it’s the way films should be done; I believe in the strength and the creativity of my directors. They need my support, not my attempts to control them.”

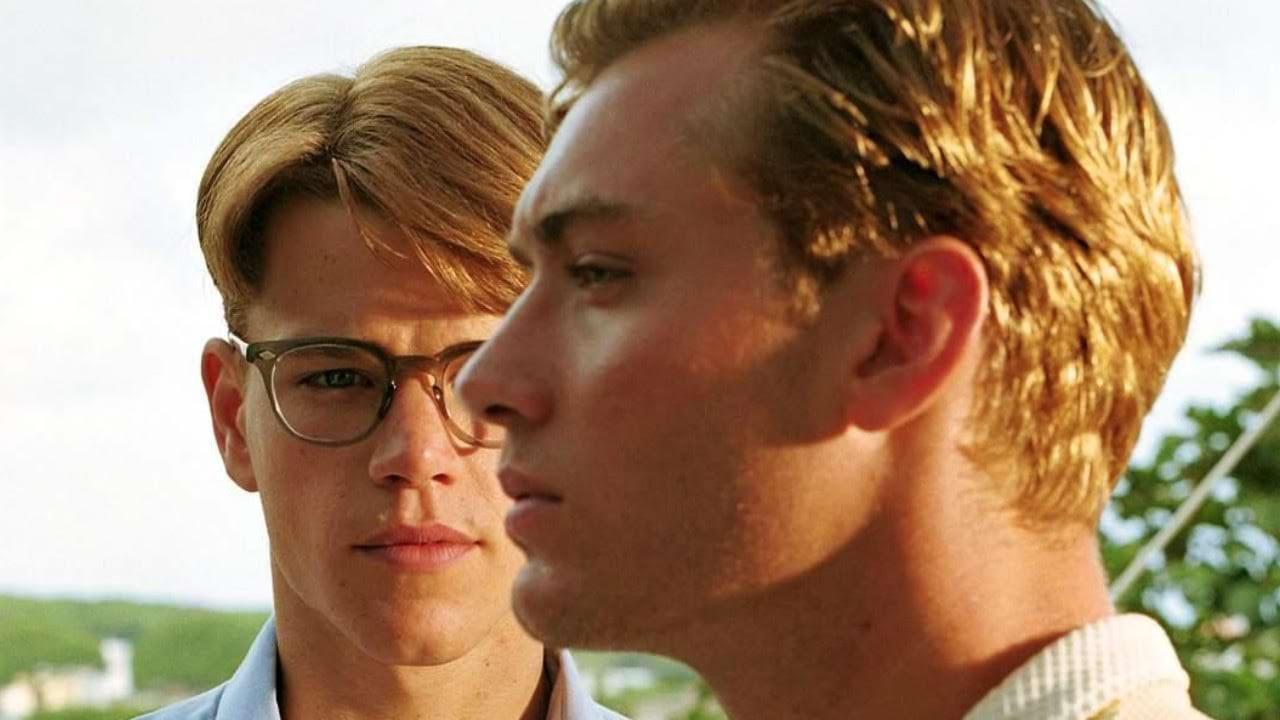

The Talented Mr. Ripley tracks the sinister exploits of Tom Ripley (Matt Damon), an opportunistic American entrepreneur and dreamer who is hired by the wealthy and powerful Herbert Greenleaf to locate his wayward son, Dickie (Jude Law), and lure him back from Europe, where he’s been leading a life of opulent frivolity. During this mission, however, the enterprising Ripley becomes obsessed with the younger Greenleaf’s extravagant lifestyle, and soon befriends him. While the duo are sailing off the coast in Greenleaf’s yacht, Ripley openly admits that he covets his friend’s flamboyant trappings. The discussion takes a dark turn, and in a fit of rage, Ripley murders the man he secretly wishes to be; when the dust settles, he realizes that he can methodically assume Greenleaf’s identity. While weaving this web of deceit, the smooth-talking Ripley manages to escape punishment and detection long enough to plunge himself deeper and deeper into the purgatory of his own desires.

“The beginning of the film is very pretty,” Seale notes. “It’s all about sailing, jazz and the beauty of the Italian Riveria. After Ripley kills Greenleaf, the film could very well have changed gears to become a much darker, colder, and more contrasty movie — which is a classic way of portraying the fact that the main character is now a murderer. We opted not to take that path, however. This story isn’t about Ripley deliberately becoming a murderer; he does so out of a very sad circumstance. Instead, we decided to keep Italy a happy, sunny place where this darkness occurs within Ripley. The life-and-death cycle has gone on for thousands of years there, and this is just another story in that long history.”

Minghella agrees, “Nature is hugely indifferent to what is going on. The film is lit with warm hues that serve to collect what is innately gorgeous about the landscape, and completely contradict the rather purgatorial journey that we are being led on. Rather than present Mr. Ripley as a collection of monochrome and increasingly moody images full of presentiment, we decided it would be much more interesting to do absolutely the reverse, and lend the film a romantic look that would stand in counterpoint to the action.

“I don’t ever begin a film with a manifesto about how we should shoot it,” Minghella adds. “I begin by collaborating with the people I trust the most to bring the screenplay to life. John and I have a very successful partnership in that neither of us are iconoclastic. We both try to learn from the screenplay and arrive at a general approach to the film through the story. For The Talented Mr. Ripley, I had two basic ideas that I brought to the table in terms of how we might shape this film. The first idea was to relocate the story from the mid-1950s to the end of the decade. During the late 1950s, Italy was going through a period of near revolution called ‘II Boom,’ when the country was emerging from the doldrums of the Second World War. There was new money in the country, and it was a resurgent period when the people were able to begin dressing and traveling with a certain style and an eye for elegance. Suddenly there were Lambrettas and Vespas everywhere, along with Italian suits and the new look of Italy. I thought that would be a much more pungent visual landscape.

“That was also the period when La Dolce Vita was being shot, and I always had this romantic notion that if we were shooting on one street, Fellini might have been around the corner shooting that picture on another. Certainly, I watched that film with all of my collaborators prior to starting Ripley, because in some ways it is — like all films shot in their own contemporary time — a documentary as well as a fictional piece. When you’re watching that type of film, you can see what the streets looked like, what people were wearing and which cars were being driven. From La Dolce Vita, you can also get a sense of how Italy expressed itself during that time. Our job was to try to reproduce that feeling in this film.”

Seale chose to capture “The Sweet Life” entirely on Eastman Kodak’s EXR 500T 5298. “I’ve almost always used the high-speed Kodak stock,” he attests. “Day, night, interior, exterior — I use just the one stock. I find that it helps considerably in being able to shoot exteriors with failing light or to start shooting earlier in the morning. You can use lenses that are slow and not worry about having to add a lot of light. Also, in combination with the Panavision [Platinum] cameras, I can just ND the film [with behind-the-lens filters] to whatever [ISO] I want, bringing it down by 20, 40, 60, 80 or whatever I need. If my first AC needs a bit more focus, I can pull out some of the ND and give him more depth of field. I simply have much more flexibility all around with the high-speed stock, which I always rate at 400 [ISO]. It gives me a little bit up my sleeve with a denser negative. Also, if I force-develop at all, I’ll only rate it another ½ to ⅔ of a stop, because I don’t think we ever get a full one-stop push from the lab. In that case, I’ll rate the stock at 640 [ISO] and play it a bit safe.

“Something I love to do, as I am unashamedly a reality cameraman, is to see where nature would put the light or where man has put the light in a building or on a street. Then, I’ll usually enhance that same lighting to a photographic level at which I can shoot. Obviously, highspeed stock gets me there a bit more quickly.

“I’m a very simple person, and I think I shoot very simply,” Seale asserts. “I set out to make the film as best as I can rather than to adorn it with incredible visual style. Most of the directors that I’ve had the privilege to work with love the reality of life. I’d much rather photograph that reality than alter it just so it will look pretty.”

When it comes to hardware, the cinematographer testifies that he has always been a “Panavision man.” He maintains, “Their equipment is very operator-friendly, and I love their Primo lenses, especially the 11:1 Primo zoom, which I believe should get an Academy Award — it’s a scorchingly amazing lens! I find myself using zooms much more often than most other cinematographers I know, and the 11:1 is a beautiful piece of optical equipment. Its contrast is fantastic — so much better than the 5:1, and that was always a good lens. It’s also a T2.8, which is wonderfully fast for a zoom. You could theoretically bolt it to the front of the camera and shoot a whole picture with it — which I practically do! It has just a slight limitation on the wider end of its range [24-275mm].

“It used to be that the optics in zooms were substantially inferior in quality to the primes, but not now — the differences between primes and zooms are practically nonexistent, especially with the Primo series. Primes still have a better optical clarity than zooms do, but it isn’t a far better clarity, and to me it’s not enough to sacrifice using the zoom. Some people may worry that I’m using the zoom as a zoom, and I suppose sometimes I do — but I also use the zoom as a multi-focal-length lens that I can adjust in shot whenever the camera or the actor moves. I love to operate. With a zoom I can tighten up the frame gently or loosen up a bit to provide much more freedom for the actors to do what they want. I’ll get in awful trouble [with other cinematographers] for saying this, but sometimes I’ll move the camera just so I can tighten the zoom. I’ve learned that if you can pan while you’re zooming, even slightly, you won’t notice the zoom.

“When I do get to operate, I use a head like a documentary camera with the Microforce zoom control attached on the pan handle. Some people hate it, but I love it — I just gently press the button so the zoom will start to creep in. You have to look at the edges of the frame to know that it’s moving. I love to use the zoom as a visual tool; it has a wonderful power that I can’t work without. A prime lens to me is held in the truck for high-speed work. I’ll always carry a T1.1 55mm lens for scenes involving cigarettes or match-lighting, or if I suddenly need a highspeed lens at the end of the day. I also carry a little set for handheld and Steadicam work, but as far as I’m concerned, the rest of the movie is shot on zooms. It gives me the ability to be able to change the focal length during the shot or between takes without wasting a lot of time.

“I love working fast,” Seale continues. “I believe that everybody’s brain stays honed to what they’re doing if you keep moving along. If anyone has time to stop and think about what they’d rather be doing, then I think they’re bored, and nobody should be bored on a film set. Therefore, I always try to move as fast as I can. When I was shooting Rain Man for Barry Levinson, we were moving along at a nice clip, and Dustin [Hoffman] came up to me and said, ‘God we’re working so fast I haven’t got time to get out of character.’ I thought about that comment for a long time. If we’re shooting so fast that an actor hasn’t got time to slip out of character, surely that must be better for the film.

“One of the things I can do to make sure we’re moving fast is to always pre-light in my mind. If I’m working with a good gaffer, it makes things much easier. Sometimes if I’m with a new gaffer, we’ll get to the end of a shot and the AD will say, ‘Okay, check the gate — gate’s clean,’ and in the next minute the set is suddenly cleared of all the lights! I’ve already lit the reverse in my mind using those lights, though, so I’ll tell them to stop [removing the lights]. I’ll take the gaffer aside and say, ‘Hey, the way I love to work is that I just leave the set hot all the time. Don’t move a lamp after we’ve finished a shot, because you’re just going to overwork everybody when I bring it back.’ As a result, the set sometimes looks like a jumble, but in my mind’s eye, I can quickly see that we’re going to use that lamp for the fill, that the backlight will become the key, and that the fill will become the backlight.

With a really great gaffer like Morris Flam, who knows my style but also has his own eye, things become that much better. On a reverse, we’ll swing the camera around and quickly re-patch a few lights. Suddenly, 10 minutes later, you’ve got it trimmed, the actor is back in front of the camera, and you’re rolling on a 180-degree turnaround. I think that’s very essential, because it keeps everybody busy and maintains the momentum.”

Gaffer Flam has previously collaborated with Seale on six features, including Dead Poets Society and The English Patient. “The best part about working with John is that the job is always about filmmaking,” he submits. “The lighting is important, but the story is of paramount importance. John will always sacrifice the lighting or a camera move if it helps to tell a better story. He always says, ‘If you make a good movie and tell a good story, then your lighting looks really good. If the story’s not as good, then no matter what your lighting is like, it will never look as good.’ I definitely concur with that concept.

“On Ripley, we responded to the script and the locations,” Flam continues. “John has a pretty pragmatic and simple approach to lighting. We try to facilitate the production by accommodating the schedule, and on this project there was a lot of moving around. We had 82 locations in nine different cities throughout Italy, so we had to be pretty mobile and flexible. With John, we’ll light the wide shot as efficiently as possible, so there won’t be a lot of adjustments between the setups. We may add a bit of fill or do a quick change, but the ideal is to be pretty much ready to go from the start. We try to figure out a way to light the whole scene and keep the lights hidden so that we can turn around without a lot of effort.”

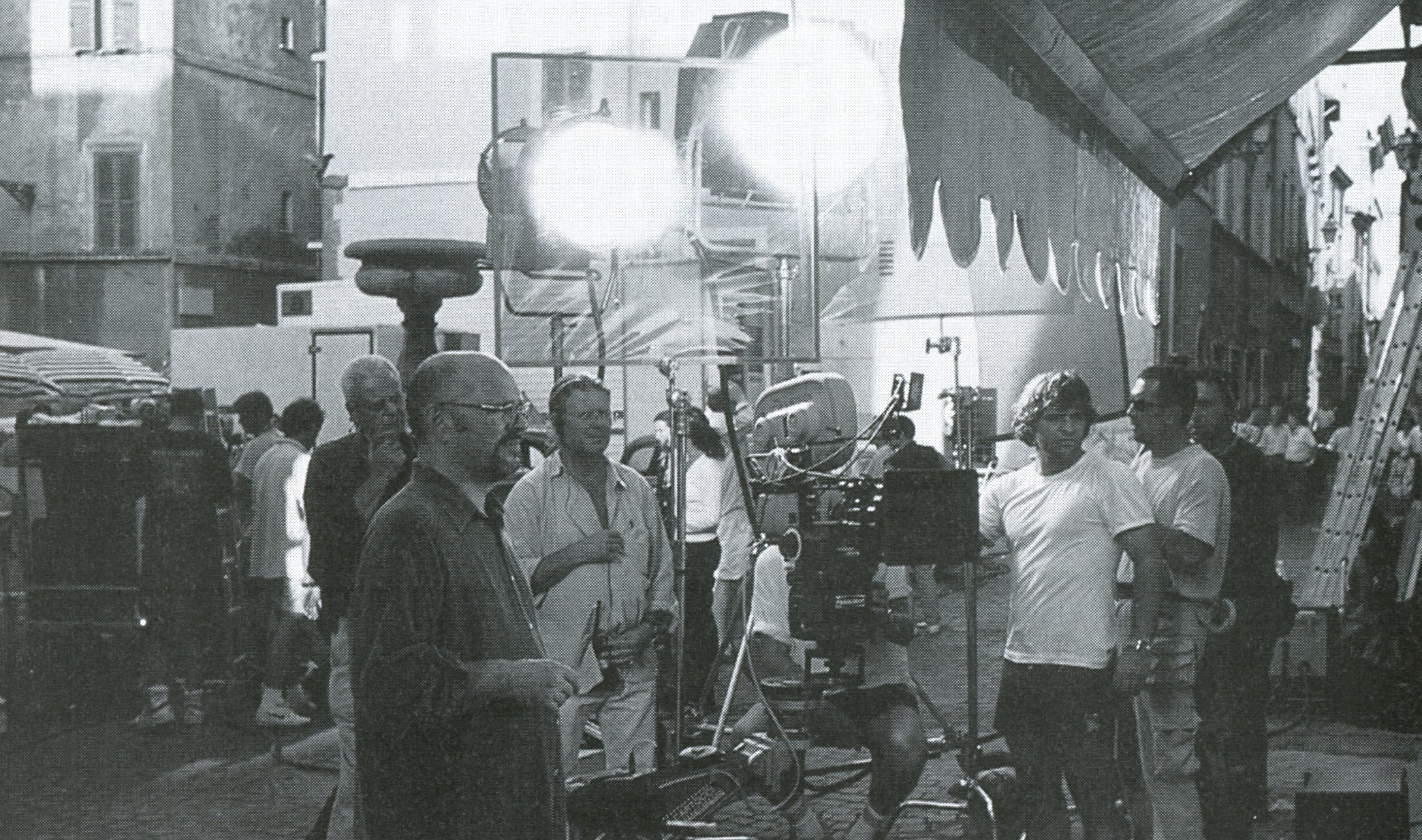

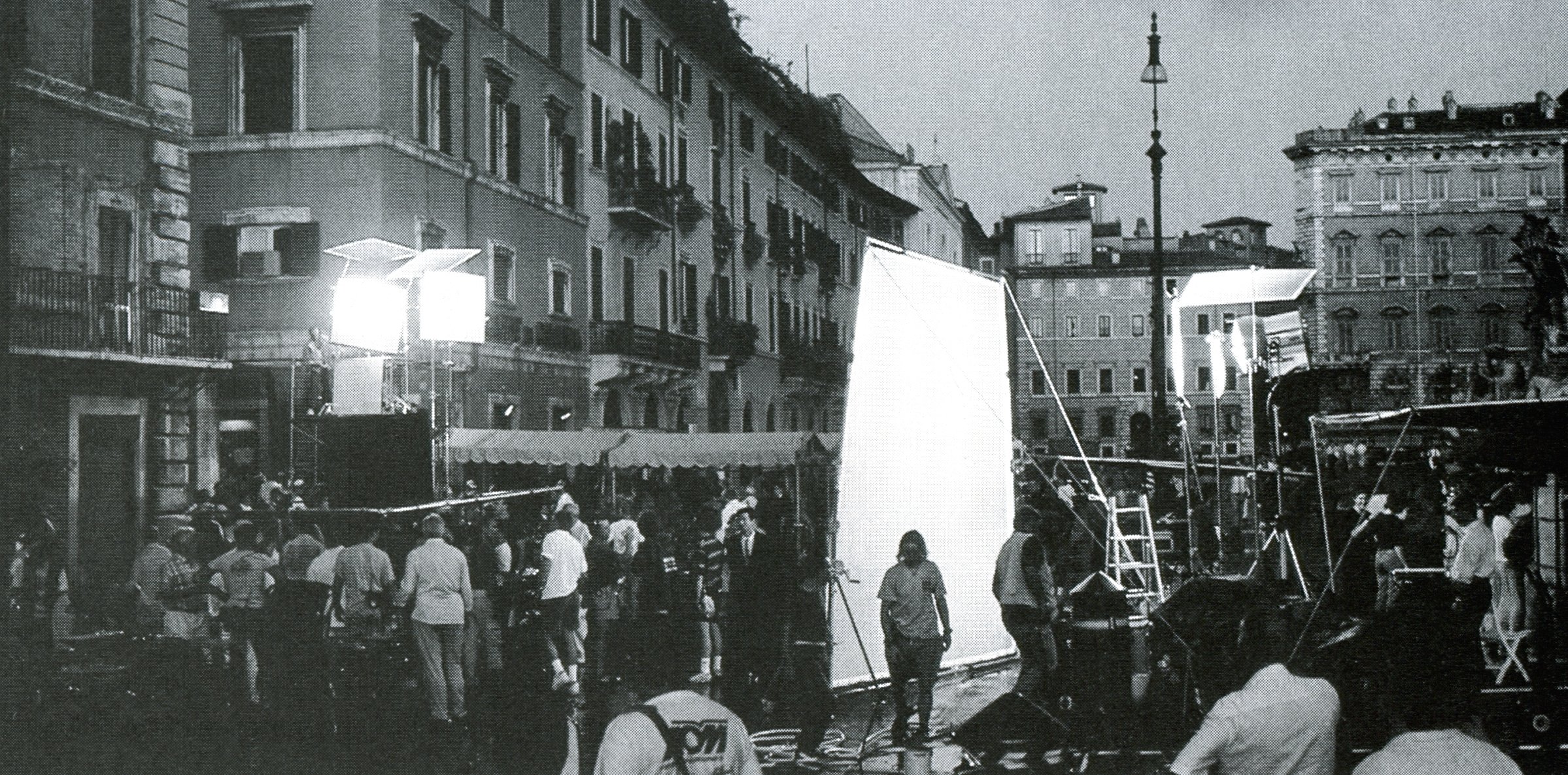

The filmmakers began shooting in Rome on August 10, 1999 atop Capitoline Hill, where Ripley surveys the ruins of the ancient Forum. He then strolls across the Campodoglio and enters the Capitoline Museum, where he observes fragments of the Colossus. The first unit then moved to Piazza Mattei and to Piazza di Spagna, the site of the Spanish Steps. After that, the production filmed inside the elegant 14th-century Palazzo Taverna in Rome’s center, where an imposing entrance lobby and grand staircase served as the entryway within Ripley’s Palazzo Gioia apartment. Further locations included the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona; the mosaic-walled Chiesa Martorana (an historic 14th-century church in Piazza Bellini); a month of shooting on the island of Ischia (a volcanic mass in the Gulf of Naples that is famous for its beautiful beaches and mineral hot springs); Palermo; Anzio; Porto Ercole in Tuscany; on the prow of a vaporetto cutting through the waters of the Grand Canal in Venice; Piazza San March; the Europa Regina Hotel; and a score of other locations in and around Italy’s famous landmarks.

“At one point, I wrote down an idea that seemed integral to the film,” Minghella recalls. “I thought we should go to landmark locations not simply to make the film look good, but because the central character himself is preoccupied with culture. All of us have a certain preoccupation with historical locations when we travel. We want to be photographed against landmarks, as a way of authenticating our journey — to prove to ourselves that we were there. Since that is the title character’s preoccupation, it also had to be the film’s preoccupation. We had to present the locations in Italy with which Ripley himself was obsessed — the picture had to be a travelogue as well as a fictional story. I was determined to visit the Spanish steps of Rome, the Piazza Navona, the Piazza del Marco and the Grand Canal in Venice.

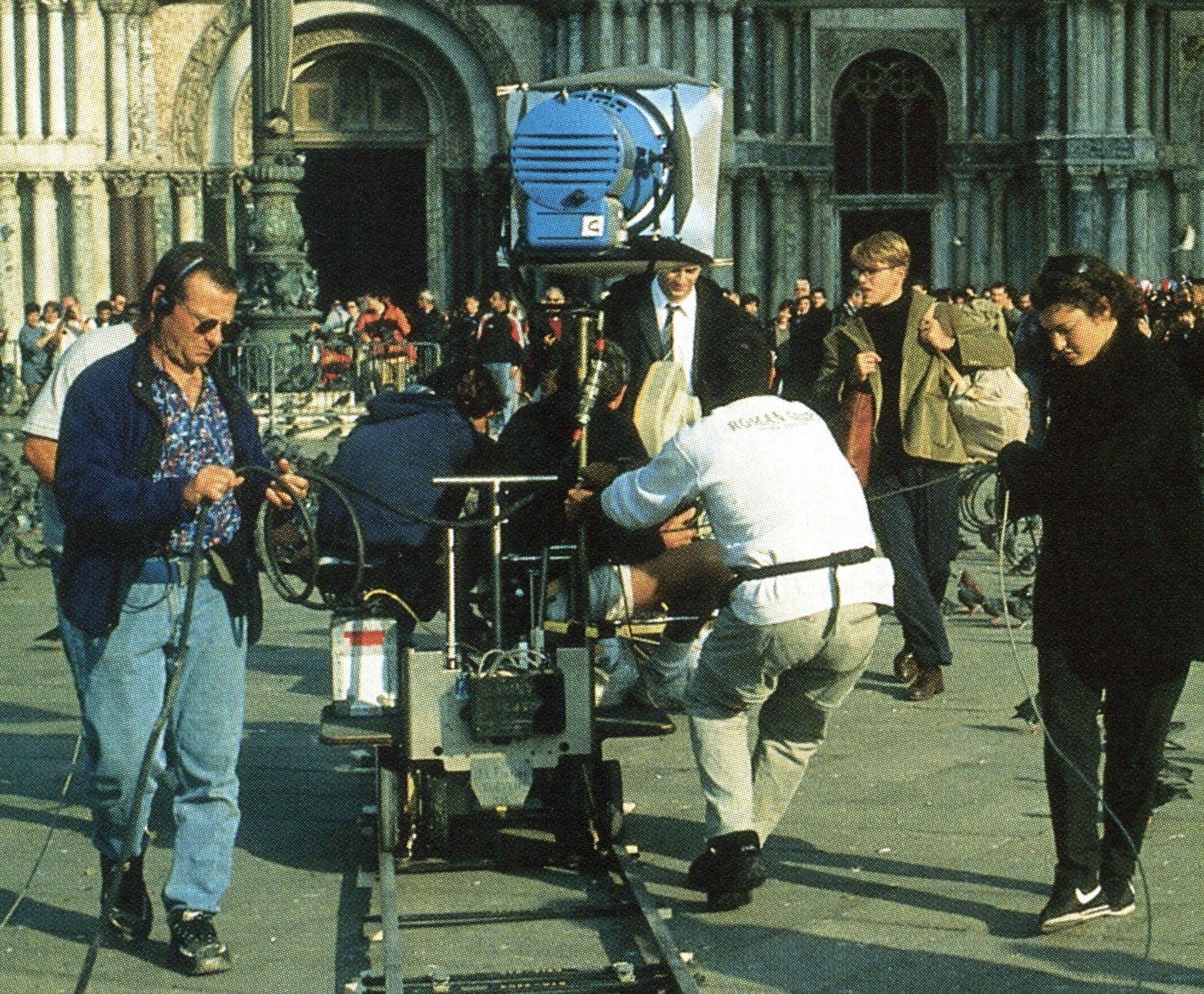

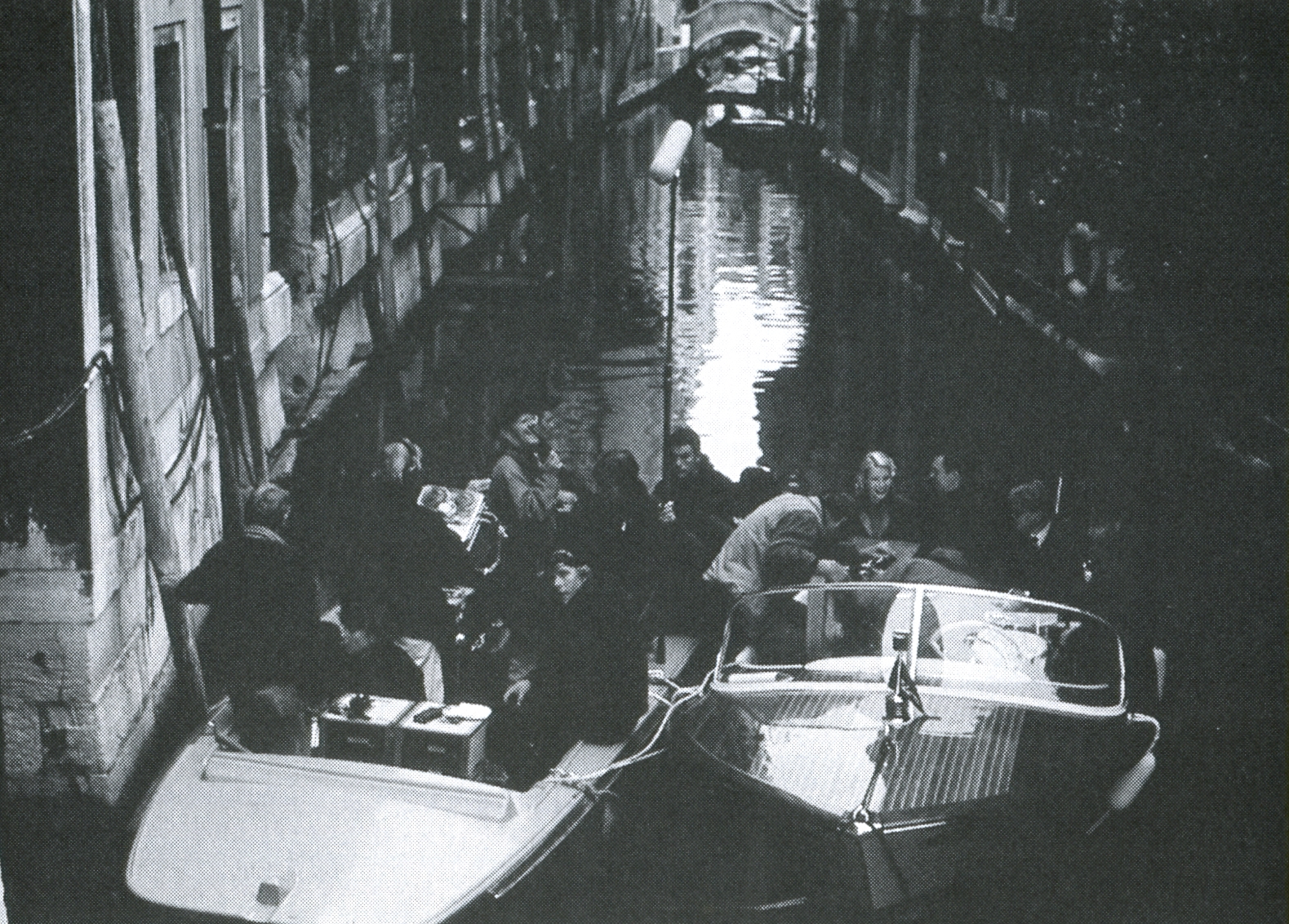

“Part of the job was to put Ripley in those places, but that forced us to work in a series of key locations that are entirely unfriendly to filmmakers. All of those locations are places that, as a filmmaker, you would normally never elect to go to, because they make shooting so difficult. Trying to re-create a more desultory and quiet time in Rome amidst the blizzard of visitors near the end of a century is more than crazy. There were literally thousands of people at each of our locations, and none of them were in period costumes! To simply to get a clean shot with a character who moved 180 degrees or more was a logistical nightmare that placed unimaginable demands on the production team. It required a kind of ‘smash-and-grab’ shooting style. During a key scene in which Ripley’s girlfriend Marge [Gwyneth Paltrow] leaves Venice, we were shooting on a launch on the Grand Canal. Of course, you can’t close the Grand Canal, because it’s a main thoroughfare. We had ADs controlling period events in the foreground and background, but sometimes — in the deep background, and even at times in the immediate foreground — there were contemporary invasions going on. It was a very key emotional moment for our actress, so I was trying to nurture that moment and give her the space she needed, but at the same time, in the periphery of my vision, I could see an AD signaling that I had five seconds before the shot would be ruined! We weren’t just chasing the light — we were chasing the simple opportunity to shoot, and that can become very taxing on a production.”

“I don’t really have a preference for shooting at locations or on sets,” Seale offers. “I find it very lovely, at times, to have a set that allows me to reach back into my memory for a certain moment in life that I can recreate to fulfill the scene. On a stage, of course, you have total control, but I think it’s also good to sometimes allow nature to control you. It keeps you on your toes, and you have to stay honed to shoot fast, because nature is not going to stop for you. As a cinematographer, it’s a good thing to be aware that you’re not always in control. Sometimes I deliberately choose a film that is exactly the opposite of my previous project, just to keep my skills in check. I’ll do a jungle film or a desert film, and then I’ll do an interior film that’s almost entirely on stage.

On Ripley, we’d go off to Ischia for five weeks to do a lot of exteriors that were controlled by weather patterns, then run to Rome and shoot within the totally controlled Cinecitta Studios stages, and then head north to Venice and shoot ‘out of control’ again. That type of work is very challenging, and it poses a lot of questions in your mind. Where is the sun going to coming up? How long will it stay? Should we start shooting a scene with the sun in shot, since it will be gone in half an hour? Can we replace it? On the Grand Canal, I certainly couldn’t — I could not get a crane with a light high enough to create a sun. All of those logistical problems keep your mind working as you try to find the best method that will keep the production rolling.”

“John has an amazing ability to solve problems creatively,” Minghella attests. “He has skills that were not necessarily learned in the lavish cinema industry of Hollywood, but in the much poorer cinema industry of Australia. He’s always got a way of solving things in-camera. He celebrates the ‘poor man’s process,’ and it’s always amazing to watch him quickly surmount some colossal problem with an ingenious yet simple solution.”

Seale adds, “I often say to Mo, ‘Gee, I wonder what other cameramen would think if they knew I was doing this.’ He’s so lovely, because he always tells me it doesn’t matter — that it’s going to work. I do break the rules a lot when I’m working on a film. If I can’t light it the way I want, I’ll sometimes throw a scene away; I just light it so that it can be recorded as well as possible for the moment, and then move on. I believe in the flavor of the entire film. To be totally honest, sometimes I feel that if I ‘win’ every scene — if every shot is exactly the way I want it — the film can have a certain sameness all the way through. Whereas if I aim more for reality and suddenly they’re on my back saying, ‘Come on! We’ve got to get this quick!’ I might not get to light the scene quite the way that I would if I had the time. In that case, I’ll just open up another half-stop and shoot it. I don’t want to control the pacing of the film with my work. I believe that the final result of the film is what we’re all going for, and that cinematography is merely a cog in that machine — along with the editing, the costume design and the production design. I’m just one of those elements that come together for the director to make a film. If one area gets more power, then it takes some power from somewhere else and begins to control the entire film. Over the years, I’ve learned that that shouldn’t happen. We all should work together as much as possible to make the best film we can. If the film is good, the audience will still walk out and say, ‘It looked good, didn’t it?’

“In August, which is the hottest month of the year, Rome always has a soft, white overcast sky that provides a nice bit of fill,” Seale continues. “It’s not the high-contrast look that you get in other areas of the world, with an acid blue sky and a burning sun. Those conditions can sometimes be hard to handle.”

Flam details, “With the overcast look, we were able to build in our own contrast to suit our needs. One of our best friends in Rome was the Arriflex 12K Par. It’s lightweight, which makes it considerably more portable and versatile than an 18K, and it packs much more of a powerful punch. Making a film is sort of like going to war — you have a limited number of weapons that you can bring with you, and those weapons have to do a lot of different things. The 12K Par is an extremely flexible tool. It can work as a really hard source, and it can work just as well as a strong soft source. Even if you’re going through heavy diffusion — which we rarely did, because John mainly likes Silent Frost and Hilite — the 12Ks still have a lot of punch. They’re easy to put on a scaffold or pretty much anywhere. The only bad thing is that they’re so hot that they’re hard to gel. If you’re working spotty, you’re going to have a hard time putting anything in front of a 12K without burning through it in a couple of seconds. Still, it’s a very realistic light that can look like the sun. Sometimes lights just can’t compete with sunlight, or they don’t really look real, but the 12K is capable of providing that feeling of realism. We started out the show with a couple of 18Ks and a 12K Par, but after a few weeks of shooting we were just using the 12Ks. Since you can only carry so many lights on your truck, it behooves you to pick the most versatile units.”

“I used the same crew in Italy that we used on The English Patient,” the gaffer adds. “We pre-rigged everything because it was the only way we could accommodate the schedule and all of the moving. Ripley was a very ambitious film that didn’t have an extraordinary budget, given the amount of work we had to accomplish. As a result, we constantly flip-flopped crews. Our rigging crew was always at least a location ahead, getting as much prepared for our arrival as possible. But we had an amazing Italian crew, with [gaffer] Stefano Morino, who has worked with people like Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC] in the past, and [key grip] Tino Malone. They were great for dealing with the logistical problems that we faced every day. In Venice, for example, everything had to be loaded onto boats, and we had to work pretty much completely on the water. In addition to camera boats, we had a boat for our generator and a boat for all of our gear. Working on the water makes the job a lot more physically challenging. To make matters worse, Italy was in the middle of their ‘alte acqua,’ which is a super high-tide that arrives in the winter and basically submerges parts of Venice. We were shooting in Piazza San Marco, and we had to wear hip boots because the waterline was a foot or two above the pavement. The Italian crews are fairly used to working under those conditions, though; they took everything in stride and really helped us pull through.

“We had quite a challenge when we were shooting on the Ponte San Angelo, which is the bridge in front of the castle of St. Angelo. The scene was a night exterior of a horse-drawn carriage ride, and we had to light a great deal of Italy in the background, including the Vatican itself. We brought in a bunch of Jumbos, which are 16 ACL (Aircraft Landing Light) lamps that run off of 28 volts each. I find those to be really good, power-efficient lights that can be softened easily. They’re great for background lighting.

“Most of Italy nowadays is lit with sodium-vapor lights, which were nonexistent back in the Fifties,” Flam notes, “We therefore found a color combination [Vs CTO and full Plus Green on tungsten sources] to use on all of our lights to match the sodium lamps in the background. That sodium green would then be pulled out completely in the lab, and timed to create the color we wanted. With lights all over the surrounding area of Italy, that was a pretty elaborate job.”

Another integral aspect of the film’s style was the dynamic blocking of actors within the frame. Minghella explains, “Because the film is so much about which character is dominant at any given point, we talked at length about the framing of the film, and about having the balance of power shift within a frame. By having the actors moving into the frame rather than the frame moving towards the actors, we were able to control the balance of power in any given scene. For example, an actor might step closer to the camera and form his or her own close-up, thus taking the focus — either liter¬ ally or metaphorically — away from another actor in the scene. You can play the game of who is partnering who inside the frame itself. The camera becomes an observer in those shifts of power.”

Seale confirms, “I look for those types of things — moments when a shot can have power and strength. I look for a way to better tell the story in a shot. I’m a great believer in wanting to know why we are doing a particular shot. What is it doing for the film? Is it progressing the film, or is it simply covering action? From my perspective, each shot needs to progress the film. When it’s all edited together, every shot should have its own power. If we’re shooting a wide master that runs all the way through the scene, are they going to cut back to this same shot at the end? I find that very boring, because that means the last shot hasn’t progressed the story any further. That’s why I love the zoom, because even on a wide shot, I can push in slightly and change the frame a bit. These days, the audience’s visual memory is very good, and viewers will know when you’ve gone back to exactly the same shot. They might not be able to tell you precisely what happened in the shot, but they can sense that they’ve already seen it. Over the years, while working with some wonderful directors, I’ve learned that you’ve got to stay ahead of your viewers. If they’re ahead of you, then you’re in deep trouble. You shouldn’t even let the audience catch up if you can help it, because then there’s no intrigue, and they’re going to get bored. That’s why every shot should have intrigue and a power of its own. If the audience is kept guessing, and they’re involved visually, they’re riveted! I think the cinematographer should help all he can in that respect, to keep the film moving in its final edit.

“All of those things came together on Ripley,” Seale concludes. “The various elements are woven through a story where human beings get caught up in their own destinies. I love those types of movies — I love making them, and I love watching them. It’s the real people and real life up on the screen that makes such stories compelling, and I’m always proud if I can capture a little piece of that reality.”

Writer-director Steven Zaillian and cinematographer Robert Elswit, ASC revisted Highsmith’s novel for the streaming series Ripley. In this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations, the cinematographer details their distinctly different visual approach