Redefining America’s Favorite Pastime: A League of Their Own

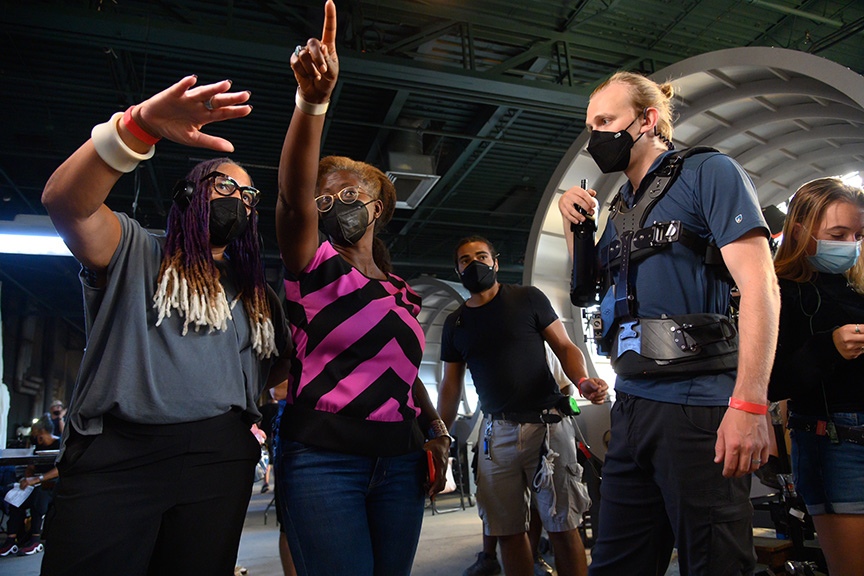

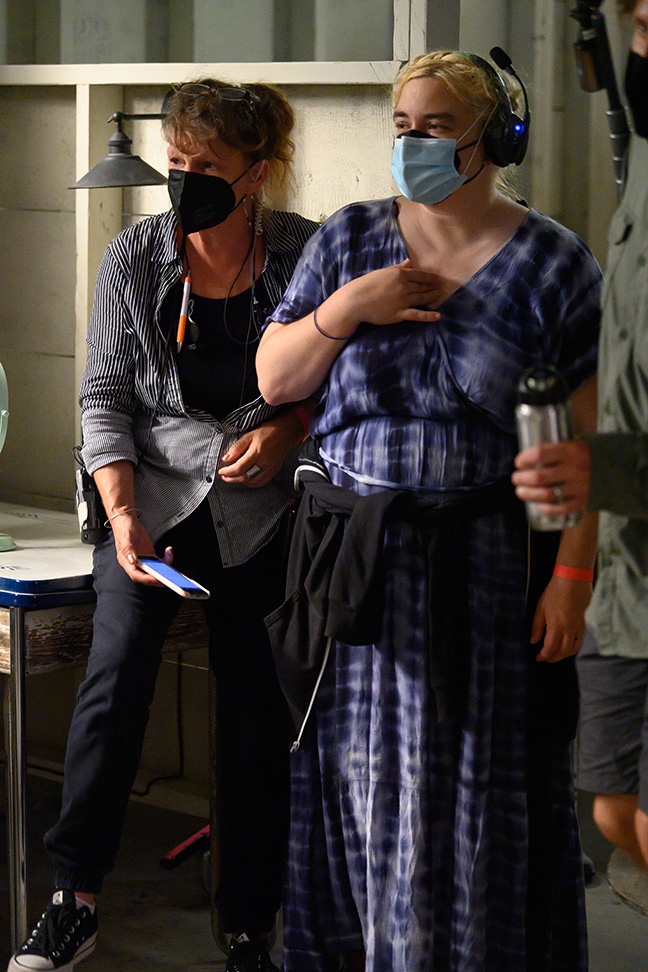

Two of AC’s 2020 Rising Stars of Cinematography, Dagmar Weaver-Madsen and Cybel Martin, team up to shoot this Amazon Prime period sports series.

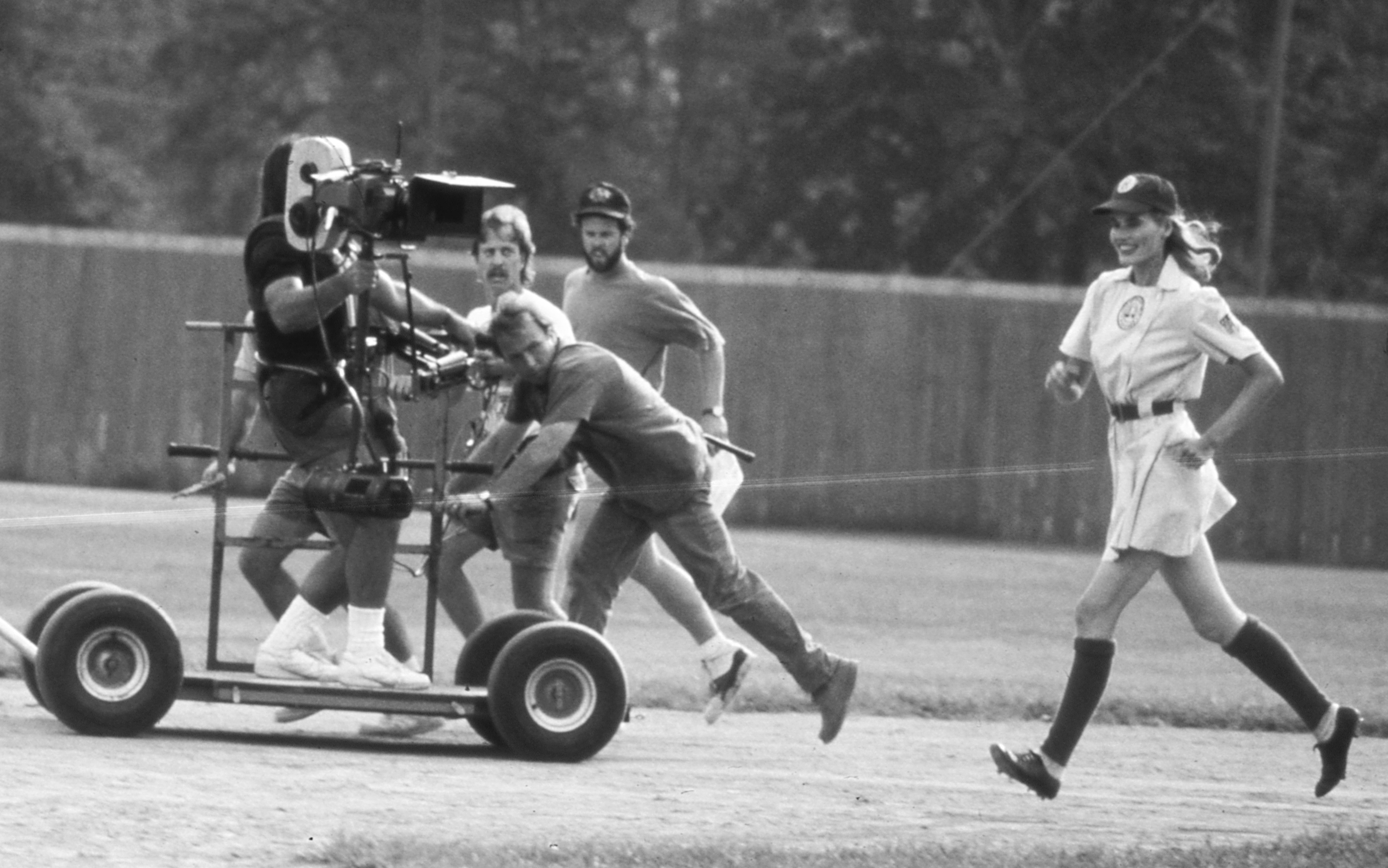

For 11 years, between 1943 and 1954, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, or AAGPBL, allowed women to do something that they have never done before or since in the United States – play professional baseball. Director Penny Marshall's beloved 1992 feature A League of Their Own tells the fictionalized story of some of those women. Starring Geena Davis and Tom Hanks, and shot by Miroslav Ondříček, ASC, it quickly became a classic.

“Everyone working on this project loves the movie and we’re definitely not trying to replace it.”

— Dagmar Weaver-Madsen

Amazon Prime’s new series of the same name, created by Will Graham and Abbi Jacobson, finds itself paying homage to the original film while rounding different bases. Creator Jacobson stars as Rockford Peaches’ catcher Carson Shaw, a housewife discovering herself while her husband is fighting abroad during World War II. The series focuses on the stories of those who were not highlighted in the original film, including women of color, many of whom were not allowed to play in the AAGPBL. The series also focuses on the queer identity of many of the players within the league, a documented fact about the AAGPBL that was only insinuated in the 1992 film.

The A League of Their Own pilot was shot by Jeffrey Waldron, while the remaining seven episodes were alternatingly shot by AC 2020 Rising Stars of Cinematography alumni Dagmar Weaver-Madsen and Cybel Martin. All eight episodes were photographed with Sony Venice cameras in 6K with Zeiss Supreme lenses. Weaver-Madsen notes, “I chatted with Jeff [Waldron] beforehand, just trying to get into his mindset and preserve the look that had been established in the pilot. We talked about how a lot of the pilot takes place in Chicago, and so it can be a little bit different looking, because it's before Carson goes to Rockford. We tried to preserve the look that had been identified, but then, he also said, ’Make it your own and grow it and do stuff that's interesting to you.’”

“On any show, you're constantly learning how best to shoot your locations. Same thing with your talent — how best to light them, how to approach them, what works well.”

— Cybel Martin

Weaver-Madsen was the first cinematographer to be brought on after the pilot was picked up. She recommended Martin as the other cinematographer for the series: “Cybel is great at street photography. One of the reasons I recommended her for this was that I really liked the way she sees people.” Both cinematographers credit their success partially to the communication they were able to have with each other.

Martin emphasizes the collaboration that she was able to foster with Weaver-Madsen on the series, explaining, “On any show, you're constantly learning how best to shoot your locations. Same thing with your talent — how best to light them, how to approach them, what works well. With us, it was just constant dialogue. It was very supportive. Sometimes on a series, you feel like you are off shooting your episodes, and they're off shooting their episodes, which is totally a fine arrangement. But we just happened to be in dialogue constantly, and that was really fun because I like her as a person and respect her. So it was easy.”

For Weaver-Madsen, as well as Martin, the original film was more of an inspiration than a reference. Weaver-Madsen explains, “I've always been a huge fan of the movie. So when my agent first told me about this, I was like, ‘I don't know if I want to do this. Why are we remaking the movie?’ They were very quick to tell me they were not remaking the movie, we're highlighting stories that didn't get to be told before. You can think of it as being in the same universe, but it's not a remake. Everyone working on this project loves the movie and we’re definitely not trying to replace it.”

In order to create the 1940s look of the show, copious amounts of research were necessary, starting with an 180-page research packet put together by the producers. Both cinematographers did their own research into photography of the time, referencing Vivian Maier, Ruth Orkin, Helen Levitt and Gordon Parks. Martin notes how period photographs helped inspire framing: “We had lots of conversations about how to portray our characters in public spaces. We wanted to bookend them. You see a lot of that in Gordon Parks photography, where there'll be the main character in the center of the frame and there are just regular people bookending on either side of the frame. We used those compositions to inform how they would show themselves in public, because they're in some way closeting their true nature in public spaces.”

The colors utilized in period photographs were also a major inspiration for creating the look of the show. Weaver-Madsen is quick to reference particular photos, citing both the reds of Vivian Maier and the greens of Helen Levitt: “I talked with Jaime O’Bradovich at Company 3, who I've worked with for many, many years as my colorist. I showed him all of these period photos and was like, ‘Hey, this is the color world we want to be in. We want to reference film. We're shooting digital, but let's add a little bit of interactive grain and let's go into this color sphere and really push those tealy greens and heighten those reds.’” The pilot was re-timed to meld with the color aesthetic created by Waver-Madsen and Martin for the rest of the episodes.

Warmth, as well as color and framing, was an important tool to create the mood of the series for Weaver-Madsen. “Something that was really important to Will and Abbi,” she explains, “and everybody working on the project, was seeing queer characters and characters of color really experiencing joy, and creating a space for this joy. I think that fed into wanting to have warmth permeate the imagery.”

One of the most powerful sequences showing the women’s joy, as well as the harsh realities of the 1940s world they lived in, was in episode 106, “Stealing Home,” shot by Martin. The episode culminates in two intercut scenes, where the characters Carson, a white AAGPBL player, and Max, a woman of color who was rejected from the league, are both able to let their guard down and experience joy at outsiders. For Carson, this is at a secret gay bar, while for Max this is at a house party.

Martin breaks down her approach: “We wanted the scenes to feel very old Hollywood romantic. There aren't many, or any, period pieces where this group is seen having joy, just living their best lives and just being joyous. Well, how do you communicate that? You want really elegant camerawork, you want really elegant framing, you want some ease. We were shooting all of this in such a short time period. One thing I pitched was to have two Steadicam operators shooting simultaneously in the bar.”

Shot in a day and a half, the bar scene benefitted from the multi-camera approach, as well as a thought-out lighting plan. “The challenge with the gay bar was that while most of the interiors of A League of Their Own were on stage,” Martin says, “the gay bar set was in the basement of our stages. We might as well have been shooting on location. We did a lot of hiding LEDs, using practicals, to support us working with the dimmer board for lighting cues. We had to get everything off the floor. At 2500 ISO on the Sony Venice, our LED lights were able to give me something really beautiful that we could mold and shape and still have a great exposure.”

The house party scene that is intercut with the bar scene was also shot on a practical location, which meant hiding lighting in a cramped space and relying on Steadicam work as well: “There's this scene where Max is dancing with S, and I love that moment, especially how it ends up matching with the dancing scenes at the gay bar. Our gaffer did this really magical thing – as the cameras are swirling one way the lights are going in a circle the other way. It's such a simple way to approach it, but it ends up being so magical.”

Multi-camera work was imperative to capturing the baseball. Weaver-Madsen and Martin often shot with three units at once during the game scenes, mixing dolly work with technocranes, rickshaw, handheld, Steadicam, and static camera work in order to create a different aesthetic for each game. Running three cameras at once allowed multiple angles and nuances to be caught in each take. Weaver-Madsen and Martin credit gaffer John Alcantara and key grip Keith Seymour with helping the extremely technical and fast paced shoots run smoothly.

Performance wise, the baseball scenes were made more challenging by the fact that the actors never threw an actual, practical baseball. The main cast went through rigorous training before shooting began, but in order to ensure that no one got injured on set, the baseballs being thrown in the series were computer-generated.

Weaver-Madsen found that communication was key to working with CG baseballs. “When we were shooting with three cameras, we would have the AD calling out what was happening [on the field],” she says, “because if you don't actually have a ball flying through the air to orchestrate and have everybody reacting to, it actually takes a lot of coordination. Everybody needs to be looking in the right place for where the ball would be going. So, there was a voice of God narrating and then they could react and do the play. I think they did so fantastic. It would have been so much easier for them if they were really playing ball.”

While the baseball games mostly relied on natural light, the one deviation from this is when the Rockford Peaches play their first night game. Shot by Martin, the game was filmed over three nights, and had the added challenge of creating realistic looking lighting for a stadium at night in the 1940s. As the Peaches play, they realize that the opposing team is turning off some of the lights in order to make it so they can’t see the ball. Martin relied on a mix of tungsten and LED lighting to create this look. “To start, I had to create a ‘movie dark,’” she says. “It has to look like night, but we still have to be able to see the actors. We used a series of Skypanel 360s around the stadium to give a sort of overall blue moonlight look. It was always a delicate balance of finding where the frame is dark and light. We used tungsten par cans in the outfield on each pole and the poles near the infield. They were placed about 30 feet in the air so they were in the shot. We researched LED options, but it was imperative that the lights look like they could belong there. Regular film lights or modern-day lights would have had to be painted out by VFX. For the blinding spotlights that hit the players, we used Astera AX10 SpotMax units aimed into the infield for that effect, along with two scissor lifts behind home plate with two SolaHyBeam 3000s per lift.”

In order to create the vintage feel of the night game, a combination of light sources were needed, employing older tungsten technology and more modern LEDS. The show found a delicate balance between being fixed in the period and adding a more modern spin to the material from a technical standpoint while staying true to the period story. Weaver-Madsen is proud of the balance that was found: “We have our anachronistic language and music, but the rest of the time, we're really rooting it in the period. When people are like, ‘Oh, this isn't how it is really,’ I can say that actually it is. Across the board. Everybody on the show was so reverent to showing that queer history exists. I think it's just so amazing to be able to be part of something that could make a difference for a lot of people. It's pretty much a dream.”