Rising Stars of Cinematography 2020

AC looks toward the future with this year’s selection of ascending directors of photography making their mark.

Profiles by Kelly Brinker, John Calhoun, Jon Silberg and Derek Stettler

Images courtesy of the filmmakers

For the fourth year running, 10 promising talents have earned a place on AC’s Rising Stars of Cinematography roster. Read on and get to know Christopher Aoun, Cybel Martin, Eric Branco, Laura Merians Gonçalves, Michael Dallatorre, Dagmar Weaver-Madsen, Drew Daniels, Cecile Zhang, Abdelsalam Moussa and Greta Zozula — a group of filmmakers with a wide array of accomplishments, influences and origin stories, and with a shared upward trajectory.

Christopher Aoun, BVK

“To me, Beirut is a city that consists of disconnected pockets right next to each other, full of contrasts,” says Christopher Aoun about his native city. The cinematographer, who has spent most of his adult life working in Germany, wanted to leave Beirut from the time he was 14. “The situation in Lebanon was very complex. I felt trapped when I was growing up, especially because of the conflicts with our neighboring countries, Israel and Syria. When I was young, I escaped through photos and imagery. I especially liked films and photographs that would make me dream of other places and other ways of seeing things.”

Aoun’s parents were Lebanese and spoke French and Arabic at home, but they sent him to a German-language school in Beirut. His father was a fashion photographer who often traveled on assignment, and his mother was a stylist. Aoun began assisting his father in the darkroom in his early teens, and by age 16, he was a working photographer himself.

He began his film studies at Saint Joseph University of Beirut, and after one year there he transferred to the University of Television and Film in Munich. “Something drew me to German culture,” he says. Much of his early work was in documentaries. To shoot Shadows of the Desert, he spent three years on and off in India, capturing intimate portraits of women whose husbands had left them. “The project gave me time to just be with the people there,” he recalls. “Not speaking the language, I developed a sense of body language and rhythm to understand what was happening. I think [documentaries are] really the best [film] school because you don’t know what’s going to happen in advance, yet you have to plan and understand what the important moments are.”

Eventually, Aoun returned to Lebanon and began shooting commercials. One of these received notice because “it was done in a very documentary style, which was very different from what people were doing there at the time,” he explains. “It was a commercial for a company that removes trash from the streets. People said, ‘We’ve never seen people doing that work portrayed so beautifully.’ That’s exactly what I try to do in my work.”

The 2018 Lebanese drama Capernaum, which Aoun shot for director Nadine Labaki, incorporates documentary techniques and is populated by young, non-professional actors. “It’s about people you would probably ignore,” he says. “I used a lot of techniques [in the photography] that many people would call ‘defects,’ such as distortion and lens flares. I like to work with those elements in a way that turns them into beauty.”

Capernaum’s crew became a family for the 90-day shoot. “My husband, Konstantin Bock, was the editor,” Aoun says, “and Nadine’s husband, Khaled Mouzanar, produced the film and composed the score. My crew lived next door. It was sort of like going on an expedition in my country.”

Shooting with Arri Alexa Mini and XT cameras and Vantage Hawk C-Series anamorphic lenses, Aoun kept gear to a minimum so the performers could feel as though they owned the spaces. He lit interiors by augmenting sunlight with HMIs and reflectors outside, and adding just a few reflectors inside. The production went on to earn an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.

Since Capernaum, Aoun has shot several German features and some commercials, and he is on the lookout for scripts. “I want to see something I haven’t seen before,” he says. “I want to be surprised.”

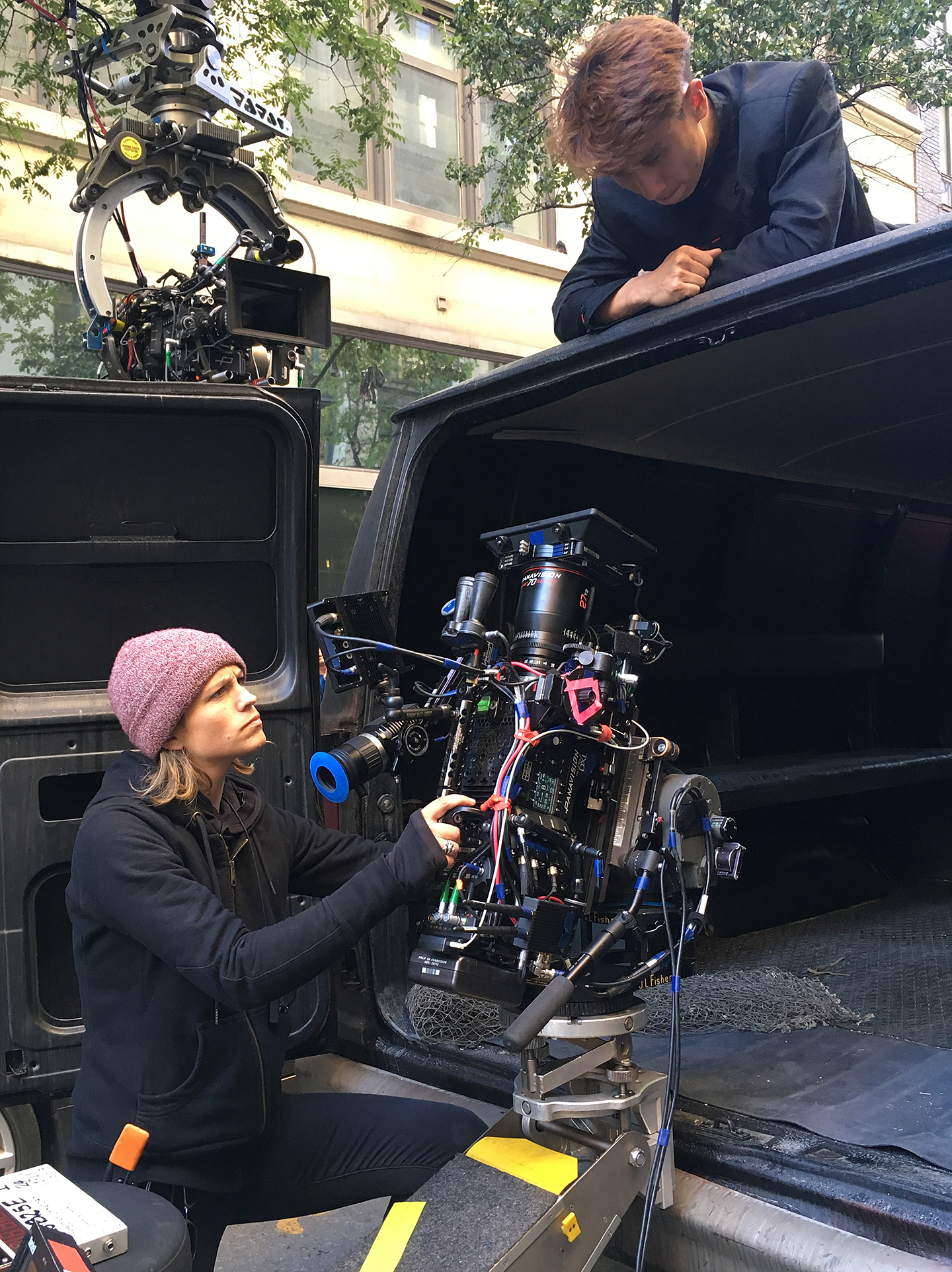

Cybel Martin

Cinematographer Cybel Martin was steeped in the visual arts from an early age. Her parents owned the New York ad agency JP Martin Associates, and film was frequently discussed in the house. She continues to be equally enthralled by documentaries, indies, international cinema, big action films, and essentially every kind of moviemaking. After graduating from New York University’s graduate-film program with an MFA and shooting indies and documentaries, her dream was to get a job on a show that had a separate truck for each department. Today, as director of photography on the CBS drama All Rise, Martin has reached that goal and then some.

As a communications major at the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned an undergraduate degree, Martin studied film theory. During that time, her fascination with cinematography gelled in Amos Vogel’s class when Martin realized how composition, lens choice and lighting played into the overall effect of Taxi Driver, shot by Michael Chapman, ASC.

After graduating from NYU, she shot her first feature, Dregs of Society, on Super 16mm in 12 days, an experience she recalls as “exhilarating.” Documentary work, she found, offered the same kind of rush, usually with the added benefit of travel. “There’s no better way to learn about yourself than to travel,” she says. She recalls that when she took her first trip to Africa, to shoot the documentary Dressed Like Kings for NYU classmate Stacey Holman, “I thought I was going to hear South African music everywhere, but when [Holman] and I asked our sound mixer to put on some music he liked, he played a Beyoncé song! It’s fascinating to come face to face with your assumptions.”

Alan Caso, ASC was particularly encouraging to Martin when he brought her onto the ABC series The Rookie to shoot second unit and work on double-up days. Martin, who is equally inspired by Michael Mann’s Heat, Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool and Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte, had a ball on the show. “I’d come in never sure what I would shoot that day,” she says. “Sometimes the whole day was gun battles, which was very exciting. I shot one of those at night. We closed down several blocks of downtown L.A. and had multiple condors, three cameras and crane shots. It was the most massive thing I’d done!”

On All Rise, Martin is pleased she can get some of her artistic sensibilities into the work. One episode, for example, “has a flashback scene that shows a bit of my character.” Judge Lola Carmichael (Simone Missick) “is usually seen in her courtroom, generally with bright L.A. light coming in. For the flashback, we created a different look, rainy and overcast — June gloom. We used Lee Silver gels on the windows to help create that look.”

On another episode, Martin added a set of wide Arri/Zeiss Ultra Primes to her camera package; for certain scenes, she wanted her camera operators to be inches away from the actors to underscore the intimacy within the Latinx community. “It took me back to my New York days of just shooting everything on a few prime lenses because that’s all we could afford,” she says with a laugh. She also added Tiffen Gold Diffusion/FX filters. “I think they add richness to darker skin tones without being obvious,” she explains.

Being a cinematographer, she sums up, “has never felt like work. I love the collaboration, the creative process and the constant problem-solving. It’s the best job on the planet!”

Eric Branco

Cinematographer Eric Branco always knew he wanted to be involved in the performing arts. “When I was 8 or 9, I decided to start taking acting classes — not because I wanted to act, but because I wanted to be involved in the process of telling a story,” he says. “When you’re a child, acting is really the only outlet available to you.”

Born and raised in The Bronx, Branco attended the School of Visual Arts, double-majoring in directing and cinematography for nearly a year and a half before leaving to pursue his career. “I realized film school was not for me,” he says, “but while there, I fell even more in love with cinematography and discovered I loved having control over how someone visually experiences a story.” He started working grip and electric on small, independent films in New York, slowly working his way up to best boy electric and eventually to gaffer. In the process, he gained valuable experience working with a range of cinematographers, including ASC members Bradford Young and Reed Morano.

While working as a gaffer, Branco got what he credits as his big break: the chance to be the cinematographer on a music video shot in Africa. “That music video had a lot more production value than anything I’d done previously, and eventually, that got me more music-video work as a director of photography. I’ve consistently tried to do good work, and I’ve been very selective about the work I do.”

Branco’s latest movie is Chinonye Chukwu’s Clemency, which won the 2019 Grand Jury Prize for dramatic feature at Sundance and was theatrically released late last year. The film called upon Branco to shift away from the frenetic handheld work to which he was accustomed. “Clemency is probably the most photographically restrained movie I’ve shot,” he says. “We were shooting in a real prison, and I tried to never have movie lights on set because I felt it was important to try and make the space feel as real as possible. I wanted the actors to feel like it was their space. Almost everything was lit through windows or rigged from above, and I tried to have all that in place before the actors walked in the door.”

That is one of Branco’s guiding beliefs: A cinematographer should never get in the way of an actor or a director, but always work with them. Given that he worked his way up from grip and electric, his philosophy of collaboration naturally extends to other members of the crew. “Just because I’m the cinematographer doesn’t mean my key grip or my gaffer won’t have a better idea than mine. I want collaborators, not manual laborers. I truly believe crews work harder and better and are happier if they have a hand in creating the image.”

Laura Merians Gonçalves

“I love being challenged and working with people who challenge me,” says cinematographer Laura Merians Gonçalves. “I like to think through our limitations and thrive. If you have the right collaborators, you can figure out how to make anything happen.”

Gonçalves grew up in a family of photographers. “We were always taking photos and looking at photography as art,” she says. Her parents encouraged her to pay attention to light, often steering family conversations toward the subject. “Cinematography is very nostalgic for me. I’m always thinking about my childhood and the spaces I lived in. Memories are my best inspiration.”

During her time at the University of California, Berkeley, she studied philosophy and “started to experiment with lighting and electricity. Something about that world really resonated with me.” After graduating, she started her journey into filmmaking as best boy electric on the 2001 feature Bully, directed by Larry Clark and shot by Steve Gainer, ASC, ASK. Gonçalves joined IATSE Local 728 and, later, ICG Local 600, and she credits the unions and her work on features, commercials, music videos and television for her real education. “Whether a job turns out to be gloriously well-received or no one ever sees it, all the work serves as learning experiences,” she says. “You have to embrace less-than-perfect results, and look at them in a positive way so that it transforms you and makes you better. The process is the result I want.”

Gonçalves never participated in professional shadowing experiences, but over the years many cinematographers have served as mentors. “I learned so much by watching others do it. Someone who looked out for me early on was the forever kind Ramsey Nickell and, more recently, Ed Lachman, ASC, whose insight and patience I am deeply thankful for. I also wrote many letters to [actor] Steve Martin looking for advice because he’s a philosopher, too, but I haven’t received his reply yet.”

Gonçalves approaches each project with an “anything is possible” attitude. “There are no rules and no absolutes. I love making images I connect with on many levels — emotionally, psychologically, physically. My intentions are to create imagery that illustrates [what I felt] when I read the screenplay. I try to distill the style of the project to a theme in one or two words. For Pacified, it was favela poetry.”

Pacified won two awards at the recent Camerimage International Film Festival: Best Cinemato-grapher’s Debut and Best Director’s Debut (for Paxton Winters). For her work on the film, Gonçalves was also awarded Best Cinematography at the 2019 San Sebastián International Film Festival and Best Cinematography at the Aruanda Film Festival in Brazil.

Her additional cinematography credits include the short Solipsist, the Netflix special John Mulaney & the Sack Lunch Bunch, and numerous other shorts, music videos and documentaries.

“Something that I would advise to future filmmakers,” the cinematographer says, “is if you have the opportunity to shoot a film in a language you don’t speak, do it! It allowed me to completely focus on the photography and made me realize how few words you need, how pared-down you can be in that way. Language, like lighting, can be kept very minimal and simplified. With some hand signals and three light bulbs, you can shoot a movie.”

Michael Dallatorre

Cinematographer Michael Dallatorre’s experience in the motion-picture business actually began in front of the camera. The Los Angeles native recalls, “I was in a performing arts group called Colors United, based out of my high school in Watts. It had formed right after the Rodney King riots.” The group of young performers became the subject of a 1997 Oscar-nominated documentary feature Colors Straight Up, directed by Michèle Ohayon and shot by Theo van de Sande, ASC.

Watching the filmmakers at work, something clicked for Dallatorre. “I had been doing stuff with my dad’s Hi8 camcorder, and I was always the one taking pictures,” he says. “But I never really thought it could be an actual job until I saw what they were doing.” A friend from Colors United helped get Dallatorre on sets as a production assistant, and after going through a summer program with Inner-City Filmmakers, he enrolled in film classes at Los Angeles Community College. “Around that time, I did a workshop with Kodak that led me to [move into prep work] at Panavision,” he says. “I asked a technician, ‘How do you get a job here?’ Two months later, I was working in the shipping department.”

After a few months, Dallatorre became a prep tech, a position he held for nine years. He was mentored by late Panavision marketing executive Phil Radin and optical engineer and ASC associate Dan Sasaki. “They’d let me take camera gear out on weekends and shoot music videos,” says Dallatore. “I’d show Phil stuff, and he’d be very excited; it was a very loving, warm family atmosphere.” He eventually moved into the marketing department and ran Panavision’s New Filmmaker Program, which loans camera packages to qualified aspirants. In 2018, he was accepted into Film Independent’s Project Involve, where he was mentored by cinematographer Pedro Luque. His work on the short Wednesday won the Best Cinematography Award at the Global Impact Film Festival.

Dallatorre’s big break was 2019’s Brightburn, directed by David Yarovesky, whom the cinematographer had worked with on music videos and shorts. One of their collaborations was a Guardians of the Galaxy-related music video for director James Gunn, who then hired them for Brightburn. “I was really fortunate,” Dallatorre says. “I was concerned that Dave was going to get a big film and they were going to say no to me. It’s not easy to jump budgets as a director of photography.”

When the next feature, Brannon Braga’s Books of Blood, came along, Dallatorre decided it was finally time to leave the Panavision nest. “It was going to be the fifth time I asked for two or three months off,” he says. “So, after 18 years at Panavision, I left, which was very difficult to do.”

Aware of his own good fortune, Dallatorre has made it a mission to mentor others. “I was a single-parent-raised immigrant from a very poor neighborhood, and to be where I am now is a blessing,” he says. “It wouldn’t have happened unless I was exposed to seeing that it was possible.” He serves on the selection committee for Children’s Defense Fund scholarships, and visits schools to spread the message that “where you’re at now isn’t where you’re going to be. There are options. I want to give them that spark others gave me as a kid.”

Dagmar Weaver-Madsen

Cinematographer Dagmar Weaver-Madsen discovered filmmaking as a child, using her father’s VHS camcorder to record plays with her sister as they grew up in Northern California. “My father is an engineer, and my mother is an English Ph.D who is passionate about storytelling,” she says. “Cinematography feels like a very natural combination [of those pursuits] because it’s technical, but at the same time it communicates story, tone and characters.”

After studying communications as an undergraduate at the University of California, Los Angeles, Weaver-Madsen applied to the school’s graduate cinematography program. She was one of just three students chosen for the program that year, which enabled her to work with a range of directors on several different projects, including one that took her to New York, where she currently resides.

In New York, a friend introduced Weaver-Madsen to Katja Blichfeld and Ben Sinclair, the creators of the Web series High Maintenance, as they were developing the show. “I thought they were very smart about storytelling and were very concise and funny,” says Weaver-Madsen. She and cinematographers Charlie Gruet and Brian Lannin, with whom she shares director of photography duties across episodes, were excited when the series took off and was picked up by HBO. They thought a bigger budget would change their shooting style, but HBO loved the look they had established during the show’s web-series beginnings. “HBO’s involvement meant that I joined the union, and that the show would reach more people,” says Weaver-Madsen. “I’m very interested in empathy and creating work that inspires people to have empathy for other people, and with High Maintenance especially, we’ve had a chance to do that.”

In addition to High Maintenance, she says, two features constitute her big break: Carlos Marques-Marcet’s 10,000 km, which opens with a 23-minute moving master shot and premiered at South by Southwest; and Kris Swanberg’s Unexpected, which premiered at Sundance. Also an important milestone for Weaver-Madsen winning the ASC William A. Fraker Student Heritage Award in 2011 for The Absence.

Weaver-Madsen is the director of photography on USA Network’s new series Dare Me, where she has had the chance to experiment with what it means to make a modern noir. “It’s really fun to do work that’s a bit darker, moodier and more colorful, to try a different set of tools and paintbrushes than I used previously; I’d been doing a lot of heightened naturalism, where things are beautiful but still realistic and sometimes gritty. It’s most important that the cinematography of a piece reflect the tone and emotional needs of the story rather than any sort of personal aesthetic.”

However, she loves cinematography that is rooted in a character’s point of view. “It’s about using all the different tools — lighting and camera-operating techniques — to bring the viewer into the character’s emotional journey,” she says. “I want the audience to feel what the characters are experiencing.

“I think it’s important to do projects that interest you and speak to you, that let you bring some of yourself to them. I hope my perspective will speak deeply to someone out there watching.”

Drew Daniels

Cinematographer Drew Daniels has been behind the camera on more than 40 shorts and features since 2009, most notably on the films of writer/director Trey Edward Shults. “A mentor once said to me, ‘Only do a film with somebody you’d want to go on a road trip with,’ and Trey is absolutely one of those people,” says Daniels.

His passion for filmmaking developed through another passion: skateboarding. Together with friends, Daniels shot and edited skate videos, finding and honing his early film language. When a close friend from that group tragically passed away, Daniels was inspired to carry on his memory and keep shooting. “He really introduced me to the camera, and he helped me see that it was possible to have a unique voice with filmmaking,” he says.

While attending film school at the University of Texas-Austin, Daniels held a range of positions on set. While observing cinematographers at work, he says, “it was immediately obvious to me that that was the job I wanted to do.” After film school, he began working on independent features in the Austin area, and he was eventually recommended to Shults. The two hit it off and have so far collaborated on three features: Krisha, It Comes at Night and Waves.

“So much of my aesthetic and technique — long single takes, 360-degree camera moves, an emphasis on natural light — were elements of the first script Trey showed me for the [earlier] short film Krisha,” Daniels recalls. The short won a cinematography award at South by Southwest in 2014, and the pair subsequently adapted it into a feature that went on to win several awards, including the Grand Jury Award and Audience Award at South by Southwest in 2015. “Trey and I are both very empathetic people, which I think is an important part of being a filmmaker,” the cinematographer says. “That’s why I work so well with him.”

Of their latest collaboration, the 2019 theatrical release Waves, the cinematographer says, “With Waves, Trey gave me the opportunity to shoot a film with really bold cinematic language. It’s very emotional and personal to him, and we put everything we had into it. I’m really proud of our collaboration. My work on Waves represents how I see the world and how I see cinema. Trey and I followed our hearts and did things in a way that felt right.”

Daniels’ credits also include Jim Cummings’ prize-winning short Thunder Road; Guy Nattiv’s Oscar-winning short Skin; and two episodes of the HBO series Euphoria.

“What I’ve learned so far is to be courageous in every aspect of the work and stay open to what the moment has to offer,” says Daniels. “As much as we might admire other filmmakers, I think the moment we try to imitate them, we’re doing a disservice to ourselves and to the film. Your own interpretation is unique, and you have to listen to that if you want to do your best work.”

Cecile Zhang

When cinematographer Cecile Zhang’s work was honored during the Pierre Angénieux ExcelLens in Cinematography ceremony at the 71st Annual Cannes Film Festival, the accolade came “totally out of the blue,” she says. The award had been given to established cinematographers for several years, but in 2018, a separate category was created to recognize promising young directors of photography. Zhang was the first recipient.

“I think it was because of my first feature, Weihai, a black-and-white art-house film that was sent to Cannes,” she says. She was proud of the movie and had a strong connection with the director, Liang Huan, “but if I look back now, I think I could have done some things better.” If Zhang is critical of her own work, it may be partly due to her training at Beijing Film Academy, where she spent seven years learning her craft, first as an undergraduate and then in a master’s program. As she points out for the sake of comparison, “American law school is only four years.”

Zhang had entered the academy — after studying painting in her youth — at age 17, and immediately took to the collaborative environment. “Most of the time you’re alone when you’re painting, but film school is very interactive, and I liked the energy.” The emphasis was on producing work; the academy serves as a pipeline for China’s film industry, which includes features created specifically for online and television platforms as well as cinemas. By her second school year, Zhang was working as a B-camera operator for a director of photography who had graduated from the academy.

Female cinematographers are still quite rare in China, and Zhang recalls that in film school, “my classmates were all boys and they tried to help me at first. The professor yelled, ‘Don’t help her! No one will help her on set!’ But I’m also the kind of person who will show you I can do it.” Mu De Yuan, who was her master’s degree tutor and is now president of the Chinese Society of Cinematographers, was her most important mentor. “Your mentor is responsible for all your work, and you have to work for him,” Zhang explains. Because she spoke both Mandarin and English, Mu got her involved as interpreter on international projects that came to China. This exposure led her to join the International Collective of Female Cinematographers.

Zhang has already racked up a number of narrative, documentary, music video and commercial credits as a cinematographer, but, she says, “I’m still young. My best work will always be the next one, I think.” Inspired by the work of Néstor Almendros, ASC and Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, she adds, “I always try to get projects that are very different from my experience.”

When she spoke to AC, Zhang was learning to dive and shoot underwater from cinematographer John Brooks for the documentary Inspirare. “The subject is a woman who is China’s world-record holder in free diving, so about one quarter of the film is going to be underwater. They were going to hire [someone else] to do the underwater photography, but I said, ‘I will train myself to do it. If I’m not going to do the underwater part of a film that [requires that much underwater work], what kind of director of photography am I?’”

Abdelsalam Moussa

The cinematographer of the upcoming Egyptian feature About Her, Abdelsalam Moussa was born with filmmaking in his blood. His father, Maged Moussa, was a respected color timer, and his grandfather, Abdelsalam Moussa, was dean of the prestigious Egyptian High Cinema Institute. “I saw negatives on our dining table every evening,” he recalls.

Moussa planned to study animation in college, but he changed course after visiting Egyptian cinematographer Tarek El-Telmissany on set. “I saw the way he was placing the lights, moving the camera and leading the whole crew. I decided then I wanted to be a cinematographer.”

He worked as El-Telmissany’s assistant over the next five years, drawing lighting plans, tracking film stock, shutter angles, light readings and more. “I was right beside him, learning from him, until I became clapper-loader.”

Moussa attended the High Cinema Institute and shot several short features, primarily on MiniDV. As he advanced, he studied the work that Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC and Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC had done on some of his favorite films. “I read many issues of American Cinematographer, where I learned about processes like bleach bypass and ENR. I put all the information in a folder on my computer.” The more he learned about photochemical techniques, including push- and pull-processing and cross-processing, the more he wanted to employ the techniques himself. “Nobody was doing those lab processes in Egypt, but I wanted to use them in my graduation project, Time Sand. I asked the lab to do a bleach bypass on the negative, and it was the first Egyptian film to do that. It was also the last film shot on 35mm in Egypt! The lab closed two years ago. Most of its chemicals and film stock are sitting in a big fridge in my home!”

Moussa’s credits include the TV series Moga Harra and Afrah Alqoba and the feature Cactus Flower.

The fantasy/drama About Her — directed by Islam El Azzazi — was shot digitally, but Moussa believes his experience shooting and manipulating film photochemically still informs his approach and aesthetic. Set in 1930s Egypt, the movie focuses on an actress in a single location, her third-floor flat, and follows her primarily in handheld long shots as she discovers important elements of her life. In order to better control the lighting and avoid the sounds of the busy city of Cairo, the filmmakers shot at night. Shooting night-for-day, Moussa notes, “also gave me more control to light the story. I love to light the space, not just the actors.”

Moussa continues to strengthen his knowledge of technique by attending ASC Master Classes. He has completed three so far, and has especially enjoyed the sessions taught by Society members Hoyte van Hoytema, Linus Sandgren, Wally Pfister and Ed Lachman that focused on shooting with film. “It was interesting to learn that even in the United States, filmmakers have to fight to shoot on film,” he says. Moussa adds that he’s delighted to be able to practice his art, no matter the medium.

Greta Zozula

“[With] filmmakers I tend to love and respect, every image and every detail, down to the tiniest little thing, means something,” says director of photography Greta Zozula. “The lighting, composition, lens choice, color and texture of things — when you add them up — mean everything.”

Zozula is discussing an element of the inspiration behind the “observational” approach to lighting and composition in Light From Light, her second feature. The movie, which tells a story that touches on the supernatural, premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, where writer/director Paul Harrill was in competition for the Next Innovator Award. “I really like his vision,” Zozula says of Harrill. “He took something that could be a horror film but approached it more like a European drama.”

Zozula, a western Pennsylvania native, was interested in filmmaking from an early age, shooting and editing on a camcorder with her sister. “I credit my love of films to my dad, who is a huge cinephile,” she says. “Our access to independent and international films was limited, but he would often bring home a lot of those films [on video]. When I was 12 or 13, I saw films by directors like Lars von Trier, Luc Besson, Michael Haneke, Andrei Tarkovsky, Lisa Cholodenko, Kimberly Peirce and Sofia Coppola. I was a little young to understand them at the time, but they continue to influence my choices as a filmmaker today.”

At 15, Zozula was accepted into a summer New York Film Academy program in Princeton, N.J., where she “realized I could do filmmaking as a career.” Later, when she enrolled in the School of Visual Arts undergraduate-film program, “I picked cinematography as a concen-tration because it was the most hands-on program, allowing me to learn the basics of camera, lighting, production design and set etiquette.”

She started taking professional jobs while in school, dabbling in grip and electric before settling on camera. The career trajectory “made sense to me because it was a ‘ladder’ that [very clearly led] to cinematography. I wanted to work on indies because I wanted projects that were more creative and hands-on, where I could learn the craft from cinematographers I loved in a more intimate environment.” One early credit as a film loader, the 2011 indie feature Martha Marcy May Marlene, introduced Zozula to two important mentors: cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes and 1st AC Joe Anderson, the latter of whom has since become a director of photography. “I really respected Jody’s approach to cinematography — the control and care he brought to each shot and scene, how he interacted with the director, and the respect he gave to the job and to the crew,” she says. “And Joe was doing what I wanted to do at the time, and he was the person who kept bringing me onto the next projects.”

Meanwhile, she was also shooting a number of shorts, including The Immaculate Reception, which earned her an Emerging Cinematographer honor from the International Cinematographers Guild in 2014. Her first feature as a director of photography was 2018’s Never Goin’ Back, which she got on recommendation from Anderson, and which led directly to Light From Light through some of the same production team. Her latest feature, Alice Wu’s The Half of It, will air on Netflix in May.

Zozula loves the collaborative creative process with the director, “trying to understand the motivation behind the film and the characters — talking it through. Every movie requires something different, which is what I love about it.”